appendix A planting and maintenance

This section covers the basics of planning a vegetable garden, preparing the soil, starting seeds, transplanting, fertilizing, composting, using floating row covers, rotating crops, mulching, watering and installing irrigation, and maintaining vegetables.

Planning Your Vegetable Garden

Vegetables are versatile. You can interplant a few colorful varieties among your ornamentals—many vegetables grow well in the same conditions as annual flowers. Or you can add ribbons and accents of color to your existing vegetable garden. Or you can create an entire rainbow garden from rough sketch to harvest. In addition, most vegetables grow well in containers and large planter boxes.

The first step in planning any vegetable garden is choosing a suitable site. Most chefs recommend locating the edible garden as close to the kitchen as possible, and I heartily agree. Beyond that, the majority of vegetables need at least six hours of sun (eight is better)—except in warm, humid areas, where afternoon or some filtered shade is best—and good drainage.

Annual vegetables need fairly rich soil with lots of organic matter. Note the type of soil you have and how well it drains. Is it fertile and rich with organic matter? Is it so sandy that water drains too fast and few plants grow well? Or is there a hardpan under your garden that prevents roots from penetrating the soil or water from draining? Poor drainage is a fairly common problem in areas of heavy clay, especially in many parts of the Southwest with caliche soils—a very alkaline clay.

It’s important to answer such basic questions before proceeding because annual vegetables should grow quickly and with little stress to be tender and mild. Their roots need air; if the soil stays waterlogged, roots suffocate or are prone to root rot. If you are unsure of the drainage in a particular area in your garden, dig a hole about 10 inches deep and 10 inches wide where you plan to put your garden. Fill the hole with water immediately and again the following day. If there’s water in the whole eight to ten hours later, find another spot in the garden that will drain much faster. Amend the soil generously with organic matter and mound it up at least 6 to 8 inches above the ground level. Or grow your vegetables in containers. Very sandy soil that drains too fast also calls for adding copious amounts of organic matter.

Find out the garden soil pH and nutrient levels with a soil test kit purchased from a local nursery or your state’s university extension service, which can also lead you to sources of soil tests and soil experts. Most vegetables grow best in soil with a pH between 6.0 to 7.0—in other words, slightly acidic. Soil below 6.0 ties up phosphorus, potassium, and calcium, making them unavailable to plants; soil with a pH much higher than 6.5 ties up iron and zinc. As a rule, rainy climates have acidic soil that needs the pH raised, usually by adding lime; arid climates have fairly neutral or alkaline soil that needs extra organic matter to lower the pH.

After deciding where you are going to plant, it’s time to choose your plants. See “Designing a Rainbow Garden” for suggested vegetables and flowers. Be sure to select species and varieties that grow well in your climate. As a rule, gardeners in northern climates and high elevations do well with vegetables that tolerate cool and/or short-summer conditions. Many vegetable varieties bred for short seasons and most salad greens are great for these conditions. Gardeners in hot, humid climes have success with plants that tolerate diseases well and are especially heat tolerant.

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map has grouped eleven zones according to winter temperature lows, a help in choosing perennial plants but of limited use for annual vegetables. The new Sunset National Garden Book, published by Sunset Books, gives much more useful climatic information; it divides the continent into forty-five growing zones. Several regional maps describe the temperature ranges and growing season in detail. The maps are an integral part of this information-packed resource. Of additional interest to the vegetable gardener is the AHS Plant Heat-Zone Map, published by the American Horticultural Society. The heat map details twelve zones that indicate the average number of days each year when a given area experiences temperatures of 86°F or higher—the temperature at which many plants, including peas and most salad greens, begin to suffer physiological damage. In “The Rainbow Vegetable Encyclopedia” on page 21, I indicate which varieties have a low tolerance to high temperatures and those that grow well in hot weather. See the Bibliography for information on obtaining the heat map.

Other design considerations include bed size, paths, and fences. A garden of a few hundred square feet or more benefits from a path or two with the soil arranged in beds. Paths through any garden should be at least 3 feet wide to provide ample room for walking and using a wheelbarrow; beds should generally be limited to 5 feet across—the average distance a person can reach into the bed to harvest or pull weeds from both sides. Protection too is often needed, so consider putting a fence or wall around the garden to give it a stronger design and to keep out rabbits, woodchucks, and the resident dog. Assuming you have chosen a nice sunny area, selected a design, and determined that your soil drains properly, you are ready to prepare the soil.

Installing a Vegetable Garden

Preparing The Soil

To prepare the soil for a new vegetable garden, first remove large rocks and weeds. Dig out any perennial weeds, especially perennial grasses like Bermuda and quack grass. Sift the soil and closely examine each shovelful to remove every little piece of grass root or they will regrow with a vengeance. Taking up part of a lawn requires removing the sod. For a small area, this can be done with a flat spade. Removing large sections, though, warrants renting a sod cutter. Next, when the soil is not too wet, spade over the area.

Most vegetables are heavy feeders and few soils support them without supplements of lots of organic matter and nutrients. The big-three nutrients are nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K)—the elements most frequently found in fertilizers. Calcium, magnesium, and sulfur are also important plant nutrients. Plants also need a range of trace minerals for healthy growth—among them iron, zinc, boron, copper, and manganese. A soil test will indicate what your soil needs. In general, most soils benefit from at least an application of an organic nitrogen fertilizer. While it’s hard to say what your soil needs without a test, the following gives a rough idea of how much organic fertilizer to apply per 100 square feet of average soil: for nitrogen, apply blood meal at 2 pounds, or fish meal at 2¼ pounds; for phosphorus, apply 2 pounds bonemeal; for potassium, apply kelp meal according to the package, or in acidic soils 1½ pounds of wood ashes. Kelp meal also supplies most trace minerals. In subsequent years, adding so many nutrients will not be needed if composting and mulching are practiced, especially if you rotate crops and use cover crops as green manure.

After the area has been spaded, cover it with 4 or 5 inches of compost, 1 or 2 inches of well-aged manure, and any other needed fertilizers or lime. Shovel on a few more inches of compost if you live in a hot, humid climate where heat burns the compost at an accelerated rate, or if the soil is very alkaline, very sandy, or very heavy clay. Add lime at this point if the soil test indicates the garden soil is too acidic. Follow the directions on the package. Sprinkle fertilizers over the soil. Incorporate all the ingredients thoroughly by turning the soil with a spade and working the amendments into the top 8 to 12 inches. If your garden is large or the soil is very hard to work, consider using a rototiller. (When you put in a garden for the first time, a rototiller can be very helpful. However, research has shown that continued tiller use is hard on soil structure and quickly burns up valuable organic matter if used regularly.)

Finally, grade and rake the area. You are now ready to form the beds and paths. With all the added materials, the beds will be elevated above the paths—which further helps drainage. Slope the sides of the beds so that loose soil will not be easily washed or knocked onto the paths. Some gardeners add a brick or wood edging to outline the beds. Putting some sort of gravel, brick, stone, or mulch on the paths will forestall weed growth and prevent your feet from getting wet and muddy.

Before planting the garden, the last task is to provide support for vining crops like pole beans and tomatoes. There are many types of supports—from simple stakes to elaborate wire cages; whatever you choose, it’s best to install them before you plant.

Starting from Seeds

You can grow all annual vegetables from seeds. They can be started indoors in flats or other well-drained containers, outdoors in a cold frame, or, depending on the time of year, directly in the garden. When I start annual vegetables inside, I seed them in either plastic pony packs recycled from the nursery or in Styrofoam compartmentalized containers variously called plugs or seedling trays (available from mail-order garden-supply houses). Whatever type of container you use, the soil depth should be 2 to 3 inches deep. A shallower container dries out too fast; deeper soil is usually a waste of seed-starting soil and water.

Starting seeds inside gives seedlings a safe place away from slugs and birds. It also allows gardeners in cold or hot climates to get a jump on the season. Many vegetables can be started four to six weeks before the last expected frost date, then transplanted into the garden as soon as the soil is workable. Furthermore, some vegetables are sensitive to high temperatures. By starting fall crops inside in mid- or late summer, the seeds will germinate and the seedlings will get a good start and be ready for transplant outside in early fall when the weather has started to cool.

The cultural needs of seeds vary widely among species. Still, some basic rules apply to most seeding procedures. First, whether starting seeds in the ground or in a container, use loose, water-retentive soil that drains well. Good drainage is important because seeds can get waterlogged, and too much water can lead to “damping off,” a fungal disease that kills seedlings at the soil line. Commercial starting mixes are usually excellent as they have been sterilized to remove weed seeds; however, the quality varies greatly from brand to brand. I find most commercial mixes lack enough nitrogen, so I water with a weak solution of fish emulsion when planting the seeds, and again a week or so later.

Smooth the soil surface and plant the seeds at the recommended depth. Information on seed depth is included in “The Rainbow Vegetable Encyclopedia” on page 21, as well as on the back of most seed packages. Pat the seeds gently into the soil and water carefully to make the seed bed moist but not soggy. Mark the name of the plant, the variety, and the date of seeding on a plastic or wooden label; place the label at the head of the row.

If you are starting seeds in containers, put the seedling tray in a warm, but not hot, location to help seeds germinate more quickly.

When starting seeds outside, protect the seed bed with either floating row covers or bird netting to keep out critters. If slugs and snails are a problem, encircle the area with hardwood ashes or diatomaceous earth to repel them and go out at night with a flashlight to catch any that cross the barrier.

For seeds started inside, it’s imperative that they have a quality source of light immediately after they have germinated; otherwise, new seedlings will grow spindly and pale. A greenhouse, sun porch, and south-facing window with no overhang will suffice, provided the growing spot is warm. If bright ambient light is not available, use fluorescent lights, which are available from home-supply stores and specialty mail-order houses. Hang the lights just above the plants for maximum light (no farther than 3 or 4 inches away). Adjust the lights upward as the plants get taller. An alternative: If the temperature is above 60°F, I put my seedling trays outside on a table in the sun and protect them with bird netting during the day, then bring them in at night.

When seedlings have sprouted, keep them moist. If you have seeded thickly or have crowded plants, thin some. Using small scissors, cut the extra plants off, leaving the remaining seedlings an inch or so apart.

Do not transplant seedlings until they have their second set of true leaves. The first leaves that sprout from a seed are called seed leaves; they usually look different from the later-forming true leaves. If the seedlings are tender, wait until all danger of frost is past before setting them out. In fact, don’t put heat-loving tomatoes and peppers out until the weather has thoroughly warmed up and stayed that way. Young plants started indoors should be “hardened off’ before they are planted in the garden—that is, they should be put outside in a sheltered place for a few days in their containers to let them get used to the differences in external temperature, humidity, and air movement. A cold frame is perfect for hardening off plants.

Transplanting

I generally start annual vegetables from seeds, then transplant them outside. Occasionally I buy transplants from local nurseries. Before setting out transplants in the garden, I check to see if a mat of roots has formed at the bottom of the root ball. If so, I remove it or open it up so the roots won’t continue to grow in a tangled mass. I set the plant in the ground at the same height as it was in the container, pat the plant in place gently by hand, and water each plant well to remove air bubbles. I space plants so that they won’t be crowded once they’ve matured; when vegetables grow too close together, they’re prone to rot diseases and mildew. If I’m planting on a very hot day or the transplants have been in a protected greenhouse, I shade them with a shingle placed on the sunny side of the plants. Then I install my irrigation ooze tubing and mulch with a few inches of organic material. (See “Watering and Irrigation Systems” on page 95 for more information.) I keep the transplants moist but not soggy for the first few weeks.

Floating Row Covers

Among the most valuable tools for plant protection are floating row covers made of lightweight spunbond polyester or polypropylene fabric. Unfortunately, they are not particularly attractive, so they may be of limited use in a decorative rainbow garden. Laid directly over the plants, they “float” in place and protect plants against cold weather and pests.

If used correctly, row covers are a most effective pest control for cucumber, asparagus, bean, and potato beetles; squash bugs and vine borers; cabbage worms; leafhoppers; onion maggots; aphids; and leaf miners. The most lightweight covers, usually called summer-weight or insect barriers because they have little heat buildup, are useful for insect control throughout the season in all but the hottest climates. They reduce sunlight about 10 percent, which is seldom a problem unless your garden is shady. Heavier versions, sometimes called garden covers under trade names like Reemay, and Tufbell, variously block from 15 percent to 50 percent of the sunlight and guard against pests. They also raise the temperature underneath from 2°F to 7°F, which is usually enough to protect early and late crops from frost or to add warmth for heat-loving crops in cool-summer areas.

Besides effectively protecting plants from cold weather and many pests, floating row covers have numerous other advantages:

• The stronger ones protect plants from most songbirds, though not from crafty squirrels and blue jays.

• They raise the humidity around plants, a bonus in arid climates, but a problem with some crops in humid climates.

• They protect young seedlings from sunburn in summer and in high-altitude gardens.

There are a few limitations to consider:

• These covers keep out pollinating bees and must be removed when squash, melons, and cucumbers are in production.

• They are not attractive enough to use over most flower beds and in decorative settings. In fact, they make the garden look like a sorority slumber party.

• Many of the fabrics last only a year before starting to deteriorate (I use tattered small pieces to cover containers and in the bottoms of containers to keep out slugs, etc.).

• Row covers are made from petroleum products and eventually end up in the landfill.

• In very windy areas, the tunnels and floating row covers are apt to be blown away or shredded.

• The heavyweight versions reduce sunlight considerably and are useful only to help raise temperatures when frost threatens.

Rolls of the fabric, from 5 to 10 feet wide and up to 100 feet long, can be purchased from local nurseries or ordered from garden-supply catalogs. As a rule, mailorder sources have a wider selection of materials and sizes.

Before applying your row cover, fully prepare the bed and make sure it’s free of eggs, larvae, and adult pests. (For example, if instead of rotating your crops, you follow onions with onions in the same bed, you are apt to have larvae of the onion root maggot trapped under the cover with their favorite food and safe from predators!)

Then install drip irrigation if you are using it, plant your crop, and mulch (if appropriate). There are two ways to lay a row cover: either directly on the plants or stretched over wire hoops. Laying the cover directly on the plants is the easiest to install. However, laying it over hoops has the advantage of being easier to check underneath. Also, some plants are sensitive to abrasion when the wind whips the cover around, causing the plant tips to turn brown. When placing the cover directly on the plants, leave some slack so plants have room to grow. For both methods, secure the edges completely with bricks, rocks, old pieces of lumber, bent wire hangers, or U-shaped metal pins sold for this purpose.

To avoid unwanted surprises, it’s critical to look under the row covers from time to time. Check soil moisture; the fibers sometimes shed rain and overhead irrigation water. Check as well for weeds; the protective fiber aids their growth too. And most importantly, check for any insect pests that may be trapped inside.

Maintaining the Vegetable Garden

The backbone of appropriate maintenance is knowledge of your soil and weather, an ability to recognize basic water- and nutrient-deficiency symptoms, and a familiarity with the plants you grow.

Annual vegetables are growing machines. As a rule, they need to grow rapidly with few interruptions so they produce well and have few pest problems. Once the plants are in the ground, continually monitoring for nutrient deficiencies, drought, and pests can head off problems. Keep the beds weeded because weeds compete for moisture and nutrients. In normal soil, most vegetables benefit from supplemental nitrogen fertilizer. Fish emulsion and fish meal, blood meal, and chicken manure all have their virtues. Sandy or problem soils may require more nutrients to provide potassium and trace minerals. If so, apply kelp meal or kelp emulsion as well as the nitrogen sources mentioned above or add a packaged, balanced, organic vegetable fertilizer. For more specific information on fertilizing, see the individual entries in “The Rainbow Vegetable Encyclopedia” on page 21.

Weeding

Weeding is necessary to make sure unwanted plants don’t compete with and overpower your vegetables. A good small triangular hoe will help you weed a small garden if the weeds are young, few, and easily hoed. When the weeds get large or out of control, you’ll have to dedicate your muscles to a session of hand pulling. Applying a mulch is a great way to cut down on weeds; however, if there’s a big problem with slugs in your garden, the mulch gives them more places to hide. Another means of controlling weeds, especially annual weeds like crabgrass and pigweed, is a new organic preemergence herbicide made from corn gluten called Concern Weed Prevention Plus. This gluten meal inhibits the tiny feeder roots of germinating weed seeds, so they wither and die. It does not kill existing weeds. Obviously, if you use it among new seedlings or in seed beds, it kills them too, so it is only useful in areas away from very young plants.

Mulching

Mulching can save the gardener time, effort, and water. A mulch layer reduces moisture loss, prevents erosion, controls weeds, minimizes soil compaction, and moderates soil temperature. When the mulch is an organic material, it adds nutrients and organic matter to the soil as it decomposes, making heavy clay more porous, and helping sandy soil retain moisture. Mulches are often attractive additions to the garden. Applying a few inches of organic matter every spring helps keep most vegetable gardens healthy. Mulch with compost from your compost pile, pine needles, composted sawdust, straw, or one of the many agricultural byproducts like rice hulls or apple or grape pomace.

Black plastic mulch

Composting

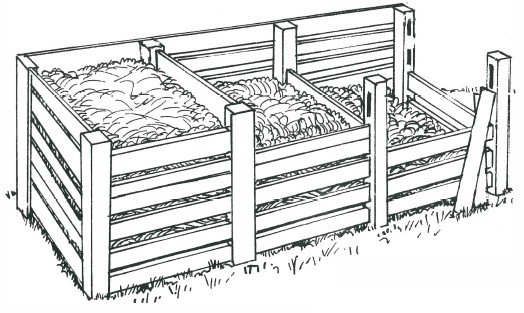

Compost is the humus-rich result of the decomposition of organic matter such as leaves and garden trimmings. The objective of maintaining a composting system is to speed up decomposition and centralize the material so you can gather it up and spread it where it will do the most good. Compost is useful as a soil additive or a mulch. Compost’s benefits include providing nutrients to plants in a slow-release, balanced fashion; helping break up clay soil; aiding sandy soil to retain moisture; and correcting pH problems. On top of that, compost is free! It can be made at home and is an excellent way to recycle our yard and kitchen “wastes.”

There need be no great mystique about composting. To create the environment where decay-promoting microorganisms do all the work, just include the following four ingredients, mixed well: three or four parts “brown” material high in carbon, such as dry leaves, dry grass, or even shredded black-and-white newspaper; one part “green” material high in nitrogen, such as fresh grass clippings, fresh garden trimmings, barnyard manure, or kitchen trimmings like pea pods and carrot tops; water in moderate amounts so the mixture is moist but not soggy; and air to supply oxygen to the microorganisms. Bury the kitchen trimmings within the pile, so as not to attract flies. Cut up any large pieces of material. Exclude weeds that have gone to seed and noxious perennial weeds such as Bermuda grass because they can carry those weeds into your garden. Do not add meat, fat, diseased plants, woody branches, or cat or dog excrement.

A three-bin composting system

I don’t get stressed about the proper proportions of compost materials, as long as there’s a fairly good mix of materials from the garden. If the decomposition is too slow, that’s usually because the pile has too much brown material, is too dry, or needs air. If the pile smells, either it is too wet or contains too much green material. To speed up decomposition, I often chop or shred the materials before adding them to the pile. I may turn the pile occasionally to encourage additional oxygen throughout. During decomposition, the materials can become quite hot and steamy, which is great; however, it is not mandatory that the compost become extremely hot.

You can make compost in a simple pile, in wire or wood bins, or in rather expensive containers. The size should be about 3 feet high, wide, and tall for the most efficient decomposition and so the pile is easily workable. It can be up to 5 feet by 5 feet, but that’s harder to manage. In a rainy climate it’s a good idea to have a cover for the compost. I like to use three bins. I collect the compost materials in one bin; the second is a working bin; when the working bin is full, I turn its contents into the last bin for final decomposition. I sift the finished compost into empty garbage cans so the nutrients don’t leach into the soil. Then the empty bin is ready to fill up again.

Crop Rotation

Crop rotation in the edible garden has been practiced for centuries for two reasons: to help prevent diseases and pests and to prevent depletion of nutrients from the soil, as some crops add nutrients and others remove them.

To rotate crops, you must know what plants are in which families as plants in the same families often are prone to the same diseases and pests and deplete the same nutrients.

The following is a short list of related vegetables:

Goosefoot family (Chenopodiaceae)—includes beets, chard, orach, spinach

Cucumber family (gourd) (Cucurbitaceae)—includes cucumbers, gourds, melons, summer squash, winter squash, pumpkins

Lily family (onion) (Liliaceae)—includes asparagus, chives, garlic, leeks, onions, Oriental chives, shallots

Mint family (Lamiaceae)—includes basil, mints, oregano, rosemary, sages, summer savory, thymes

Mustard family (cabbage) (Brassicaceae)—includes arugula, broccoli, cabbages, cauliflower, collards, cresses, kale, kohlrabi, komatsuna, mizuna, mustards, radishes, turnips

Nightshade family (Solanaceae)—includes eggplants, peppers, potatoes, tomatillos, tomatoes

Parsley family (carrot) (Apiaceae)—includes carrots, celeriac, celery, chervil, coriander (cilantro), dill, fennel, lovage, parsley, parsnips

Pea family (legumes) (Fabaceae)—includes beans, cowpeas, fava beans, lima beans, peanuts, peas, runner beans, soybeans, sugar peas

Sunflower family (composites) (Asteraceae)—includes artichokes, calendulas, celtuce, chicories, dandelions, endives, lettuces, marigolds, tarragon

The object to rotating crops is to avoid growing members of the same family in the same spot year after year. For example: cabbage, a member of the mustard family, should not be followed by radishes, a member of the same family, as both are prone to flea beetles and the flea beetle’s eggs will be in the soil ready to hatch and attack the radishes. Tomatoes should not follow eggplants, as they are both prone to fusarium wilt.

Crop rotation is also practiced to help keep the soil healthy. One family, namely the pea family (legumes), that includes not only peas and beans but also clovers and alfalfa, adds nitrogen to the soil. In contrast, most members of the mustard (cabbage) family deplete the soil of nitrogen. Members of the nightshade and cucumber families are other heavy feeders. Because most vegetables deplete the soil, knowledgeable gardeners not only rotate their beds with vegetables from different families, they also include an occasional cover crop of clover or alfalfa and other soil benefactors like buckwheat and vetch to add what’s called “green manure.” The gardener allows these crops to grow for a few months, then turns them into or under the soil. As they decompose, they provide extra organic matter and many nutrients, help stop the pest cycle, and attract beneficial insects. Some cover crops (like rye) are grown over the winter to control soil erosion. The seeds of all sorts of cover crops are available from farm suppliers and specialty seed companies. I’ve been able to give only the basics on this subject; for more information, see Shepherd Ogden’s Step by Step Organic Vegetable Gardening and some of the other basic gardening texts recommended in the Bibliography.

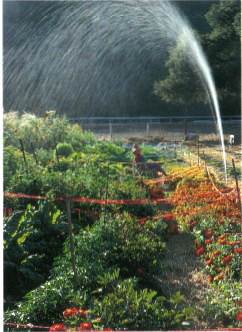

Watering and Irrigation Systems

Even gardeners who live in rainy climates may have to do supplemental watering at specific times during the growing season. Therefore, most gardeners need some sort of supplemental watering system and a knowledge of water management.

There is no easy formula for determining the correct amount or frequency of watering. Proper watering takes experience and observation. In addition to the specific watering needs of individual plants, watering requirements depends on soil type, wind conditions, and air temperature. To water properly, it’s important to learn how to recognize water-stress symptoms (often a dulling of foliage color as well as the better-known symptoms of drooping leaves and wilting), how much to water (too much is as bad as too little), and how to water. Some general rules are:

1. Water deeply. Except for seed beds, most plants need infrequent, deep watering rather than frequent, light sprinkling.

2. To ensure proper absorption, apply water at a rate slow enough to soak deeply into the soil rather than run off.

3. Do not use overhead watering systems when the wind is blowing.

4. Try to water early in the morning so foliage has time to dry before nightfall, thus preventing some disease problems. In addition, less water evaporates in cooler temperatures.

5. Test your watering system occasionally to make sure it covers the area evenly.

6. Use methods and tools that conserve water. The pistol-grip nozzle on a hose will shut off the water while you move from one container or planting bed to another. Soaker hoses, made from either canvas or recycled tires, and other ooze- and drip-irrigation systems apply water slowly and more efficiently than overhead systems.

Drip, or the related ooze/trickle, irrigation systems are advisable wherever feasible; most gardens are well-suited to them. Drip systems deliver water a drop at a time through spaghetti-like emitter tubes or plastic pipe with emitters that drip water right onto the root zone of each plant. Because of the time and effort involved in installing one or two emitters per plant, these systems work best for permanent plantings such as in rose beds, with rows of daylilies and lavender say, or with trees and shrubs. Drip lines require continual maintenance to ensure the individual emitters are not clogged.

Similar systems, called ooze systems, deliver water through either holes made every 6 or 12 inches along solid flexible tubing or ooze along the entire porous hose. Neither system is as prone to clogging as are emitters. The solid type is made of plastic and is often called laser tubing. It is pressure-compensated, which means the water flow is even throughout the length of the tubing. The high-quality brands have a built-in mechanism to minimize clogging and are made of tubing that will not expand in hot weather and, consequently, pop off its fittings. (Some of the inexpensive drip-irrigation kits can make you crazy!) The porous hose types, made from recycled tires, come in two sizes—a standard hose diameter of 1 inch, great for shrubs and trees planted in a row, and ¼-inch tubing that’s easy to snake around beds of small plants. Neither is pressure-compensated so the plants nearest the water source receive more water than those at the end of the line. It also means they will not work well if there is any slope. All types of drip emitter and ooze systems are installed after the plants are in the ground and are held in place with ground staples. To use any drip or ooze system, it’s also necessary to install an antisiphon valve at the water source to prevent dirty garden water from being drawn into the house’s drinking water and to include a filter to prevent debris from clogging the emitters.

Baby lettuces with laser tubing drip irrigation

To set up the system, connect 1-inch distribution tubing to the water source then arrange the tubing around the garden perimeter. Connect smaller-diameter drip and ooze lines to this. As you see, installing these systems requires some thought and time. You can order these systems from either a specialty mail-order garden or irrigation source or visit your local plumbing store. I find the latter to be the best solution for all my irrigation problems. Over the years, I’ve found that plumbing-supply stores offer professional-quality supplies, usually for less money than the so-called inexpensive kits available in home-supply stores and some nurseries. Their professionals also may help you work out an irrigation design tailored to your garden. Whether choosing an emitter or an ooze system or buying tubing, be prepared by bringing a rough drawing of the area to be irrigated—including dimensions, location of the water source, any slopes, and, if possible, the water pressure at the water source. Let the professionals walk you through the steps and help you pick out supplies to best fit your site.

Problems aside, all forms of drip irrigation are more efficient than furrow or standard overhead watering. They deliver water to its precise destination and are well worth considering. They provide water slowly, so it doesn’t run off; they also water deeply, which encourages deep rooting. Drip irrigation also eliminates many disease problems, and there are fewer weeds because so little soil surface is moist. Finally, drip-irrigation systems have the potential to waste a lot less water.