THE commerce of Greece and the East underwent as great a change after the conquest of Alexander and the diffusion of Hellenism in the valley of the Nile and all Western Asia as agriculture and industry. In fact, the progress of these latter forms of human activity contributed greatly to the change.

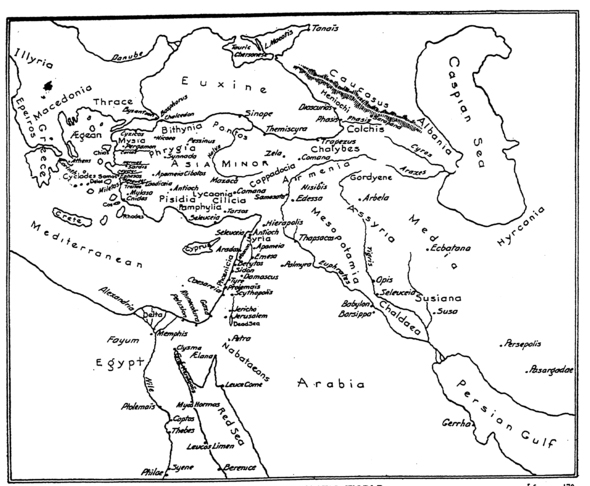

Although the regions which were divided among the kingdoms of the Successors never came to form the single huge state which Alexander had projected and even realized, they kept up daily, constant relations with one another. Over all the national or local civilizations inherited from a long and often brilliant past, Hellenism was a factor of unity in every domain. One can, therefore, treat the whole Hellenistic world as one economic whole, complex, no doubt, but having all its parts mutually connected—all the countries comprised by the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea in the west, the Sahara, Ethiopia, and Arabia in the south, Iran in the east, and the Caspian, the Caucasus, the plains of Scythia, and the wild mountain-country of the Balkans in the north.

From one end of this area to the other, the land was not all equally fertile or barren, raw materials were not equally plentiful, and human activity was not equally intense, skilful, or successful. There were valleys and plains of amazing fertility, and there were districts which were quite or almost quite uncultivated. By the Nile and the Euphrates there were endless cornfields, which were lacking in Greece Proper, the islands, and many parts of Asia Minor. The olive, which was found almost everywhere in Greece and in many parts of Asia, did not grow in Egypt. The tablelands and valleys of Asia Minor supported countless flocks of sheep, which supplied wool which was much in demand. Timber, which was plentiful on forest-clad mountains like Ida in Mysia, the Taurus in Cilicia, the Caucasus, and Lebanon, was wholly lacking along the Nile and in Babylonia. The iron-mines of the country of the Chalybes and the copper-deposits of Cyprus were the only sources of these metals in the East. The big industrial centres were distributed at intervals, from Sinope and Cyzicos in the north of Asia Minor to the Phoenician cities and Alexandria. The great economic phenomenon of division of labour and specialization, not only between individual human beings but between natural regions, developed to a hitherto unknown extent in the now much wider domain of Hellenistic civilization. The consequences were inevitable: for every foodstuff, for every raw material, for every manufactured article, commercial currents set up between the centres of production, or rather of over-production, and the countries which consumed without producing or consumed more than they produced. It is true that Greece had known movements of exchange of this kind before Alexander's time, but under the Seleucids and Lagids these movements became far more extensive. Every kind of goods now travelled across the Hellenized East and old Greece.

This movement was not confined within the limits by which the political dominion of the Greeks was ultimately bounded. The work of Alexander had broken down the barriers which had previously separated the Mediterranean world from the inner parts of Asia. Those barriers were not set up again when Iran, Bactriana, Sogdiana, and the upper valley of the Indus broke off from the empire of the Seleueids. Not only did Greeks and Hellenized Orientals go to all these countries for many foodstuffs and raw materials required by their industries, not only did they export their manufactured goods to them, but they were able to use the great routes which ran through those regions, connecting the shores of the Mediterranean with Central Asia and the Far East in one direction and with Arabia in another. At the same time, the ships of Ptolemaic Egypt began to throng the Red Sea, to pass the strait of Bab el-Mandeb, and to navigate the Indian Ocean, either along the coasts of southern Arabia and East Africa or direct to the Deccan. In this way a very extensive and truly international trade grew up, and for the first time the economic life of the ancient world came under the influence of Southern and Eastern Asia and of parts of the seaboard of Equatorial Africa.

The actual organization of the Hellenistic kingdoms dominated this commercial activity as it dominated agricultural and industrial life. Great as was the influence once exercised by the markets of Athens and the Piræus on the development of business, it cannot be compared, even remotely, to that of the Kings of Syria and Egypt. By the foundation of numerous cities at well-chosen spots, by an urban policy inspired by the example of Alexander, by their wise interest in the public works needed for the building and upkeep of ways of communication of all kinds, by their interference (perhaps too frequent and a little tyrannical, but useful) in the circulation of goods and exchanges between individuals, the Seleucids, the Attalids, and above all the Lagids showed themselves capable of taking advantage of the very favourable new conditions offered to commerce. Their subjects profited by those conditions more fully than private enterprise could have done by itself, with its necessarily limited means of action.

All these causes acted in the same direction. In spite of the wars and disturbances too often provoked by the rival ambitions of kings and the jealousies of cities, in spite of the decline into which the royal houses of Alexandria, Antioch, and Pergamon fell after a hundred years, the eastern basin of the Mediterranean now lived a very intense economic life, involving regions which had long been almost unknown to one another and now found their interests closely allied.

Of the roads which ran all over the countries of Hellenistic civilization, the most important were those connecting the shores of the Mediterranean with the regions lying away from its basin.

The northernmost of these roads was that which crossed the Caucasian isthmus, connecting the basin of the Cyros and Araxes with that of the Phasis and coming out at the eastern end of the Euxine.2 From Sarapana, " a fort which can hold the population of a city," travellers and goods went down the Phasis by water.

Through the middle of Asia Minor and the kingdom of the Seleucids ran the great route by which Sogdiana, Bactriana, and the upper valley of the Indus communicated with Mesopotamia, Syria, and the seaboard of the JSgean. It was in a way the backbone of the road-system which covered Western Asia. Strabo describes big stretches of it in various parts of his Geography. From Ephesos to Samosata on the Euphrates it ran, on the whole, apart from some detours, from west to east, by the valley of the Macander, southern Phrygia, Lycaonia, Cappadocia, and Commagene. On this stretch it touched Magnesia, Tralles, Nysa, Antioch on the Mseander, Laodiceia on the Mseander, Apamcia Cibotos, Burnt Laodiceia (Katakekaumene), Coropassos, and Mazaca.1 From Samosata, it doubtless went down the Euphrates to Babylon and Seleuceia on the Tigris; from there it traversed Media to the pass known as the Caspian Gates.2 Beyond the pass, it first kept on the northern slope of the plateau of Iran as far as Arian Alexandria (Herat), and then divided. One branch went straight on through Bactriana to Ortospana among the Paropamisadse, in the upper valley of the Cophen, a tributary of the Indus; the other diverged southwards through Drangiana, passed through Prophthasia, and then turned east and went onwards to the Indus.3 From Ortospana a road started which ran to Bactra and Sogdiana; this was the road by which the caravans came from Central Asia and the country of the Seres.4

North and south of this vital artery, other roads served more local traffic. We must suppose that there was a route which ran from the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates through western Media and Armenia to the Caucasus, which it crossed either by the Pass of Darial, the Caucasian or Sarmatian Gates of the ancients, or by the Albanian Gates near Darband on the coast of the Caspian, and went on to the country of the Aorsi, not far from where the Don and Volga approach one another; for Strabo says that the Aorsi had the monopoly of the camel-transport of goods consigned from India and Babylonia by way of Armenia and Media.5 Droysen thinks that this lucrative traffic, which was chiefly in the hands of the Armenians south of the Caucasus as it was wholly in those of the Aorsi north of that range, must have had its terminus at Seleuceia on the Tigris.1

Moreover, seleuceia and JtSabyion, situated on the Tigris and Euphrates respectively in the district where the two great rivers came close together, constituted a very important road-centre. They stood at the junction of roads from upper Persia through Susiana and from Arabia Felix through Gerrha and Chaldsea.2 There was also active intercourse with Syria. The itinerary followed by merchants travelling from Syria to Seleuceia and Babylon is thus described by Strabo:

" They cross the Euphrates at the level of Anthemusia, a place in Mesopotamia. Above the river, four schoinoi away, stands the city of Bambyce, which is also called Edessa and Hierapolis. . . . Then, after crossing the river, they go over the desert to the Babylonian frontier, and so come to Seenæ, a big town on a canal. The distance from the Euphrates crossing to Scense is reckoned at twenty-five days' journey. There are camel-men who keep khans, which are well supplied with water, mostly from cisterns but in some cases brought to the place. . . . Scenæ is eighteen stades from Seleuceia."3

The road from the Euphrates to Syria by Palmyra does not seem to have been used in Hellenistic times. The importance of Palmyra dates from the Roman Empire.4

From Arabia and Palestine, there were roads to Syria and Phœnicia. Caravans from Arabia Felix went to Damascus, but for a long time the route which they took was infested by brigands.5 Eastern Palestine and Transjordania were connected with the port of Arados by a road which followed the valleys of the Jordan and Lycos.6 South-east of Palestine, Petra was an important road-centre. It stood on roads coming from Arabia Felix and Leuce Come, the port of the Nabatæans on the Red Sea, and on one coming from Gerrha across the desert, and it was connected with Rhinocolura, a town on the Egyptian frontier between Gaza and Pelusion. Strabo speaks of Rhinocolura as a Phœnician city, and adds that the goods conveyed from Petra to it were sent on from there in every direction.1 Yet other roads served for the transport of spices from Arabia Felix to Gerrha on the Persian Gulf or to Ælana at the head of the Bay of Ælana.2

In Egypt, the land-routes chiefly served to maintain communications between the valley of the Nile and the coast of the Red Sea. When Ptolemy II Philadelphos had founded several stations on that coast, the most important being Berenice, almost exactly at the latitude of Syene, it was necessary to connect them with the river on whose banks the life of the country centred. Coptos, at the point where the Nile came nearest to the Red Sea, stood at the head of a number of roads from Myos Hormos, Leucos Limen, and Berenice. The biggest and most used was that from Berenice.

" There is a kind of isthmus between Coptos and the Red Sea at Berenice. . . . Philadelphos, they say, first built this road, using his troops for the work, and established stations along it. . . . Experience has proved its usefulness, and today all goods from India and Arabia and all Ethiopian goods which come by the Red Sea are taken to Coptos. . . . In the past merchants used to travel on their camels by night . . . taking their water with them; today there are watering-places along the road, both wells dug to a great depth and rain-water cisterns, although rain is rare in that country. This route is six or seven days long."3

In old Greece, no attempt seems to have been made to extend or improve the road-system. In Macedonia a few stretches of road were built, but it was not till later that the Via Eenatia ran continuously from the Adriatic to the Ægean.4

The conveyance of goods by land was not an unknown thing to the Greeks before Alexander's time, although they far preferred the sea. On the other hand, they had practically never attempted transport by river, except perhaps to reach their trading-station of Naucratis in the Nile Delta. The Hellenized East possessed waterways of great importance, which had been used for ages and long continued to be used under the Kings who succeeded Alexander.

From the passage of Strabo, quoted above, regarding the road which crossed the Caucasian isthmus south of the mountains, it would seem that the Phasis Avas navigable up to Sarapana, which is usually placed in the upper valley of the river. The Cyros, which flowed into the Caspian, may also have been navigable for some distance, since the same author states that the carriage-road which started from Sarapana led in four days to the banks of the Cyros. May one not suppose, from the words used by the geographer, that this overland road was simply a portage over the mountains between the waterways of the Phasis and the Cyros?1

On the Euphrates and Tigris, navigation was very active, at least on their lower waters. Vessels (by which one must understand those which had sailed up the Persian Gulf to the adjoining and almost common mouths of the two rivers) could go on the former to Babylon and on the latter to Seleuceia and even Opis, a big trading centre about seventy miles upstream from Seleuceia as the crow flies.2 In addition, rafts, which the people of Gerrha used for the transport of spices and other foodstuffs coming from Arabia, went up the Euphrates to Thapsacos, and it was not till there that their cargoes were unloaded, to be sent overland to their various destinations.3

When Alexander arrived in Chaldæa, shipping on the lower Euphrates and Tigris had been obstructed by the Persians for strategical reasons.

" From fear of invasion from outside, to make it difficult to ascend the two rivers, they had made artificial cataracts. When Alexander came, he destroyed as many of these as possible, and especially those below Opis." 4

The conqueror was also at pains to ensure the normal working of the many canals which had been dug all over Babylonia. These canals were chiefly used for irrigation, but shipping also took advantage of them, for Strabo says that it is equally injured by extreme drought and by too high water, and the only remedy in either case is to be able " to open or close the mouths of the canals quickly, so as to keep the water always at an average level and not to allow there to be either too much or too little."5 There was a canal connecting the Euphrates with the Tigris, which it joined at Seleuceia; but whether it was made by the Seleucids or existed before Alexander's time is not known. In any case, it seems certain that the Greeks did not remain content to use the water-system, natural or artificial, which existed before they settled in the country; Alexander and perhaps the first Seleucids improved it and doubtless also completed it.

Similar work was done by the Ptolemies in Egypt. Here the Nile was the great road of transport from Syene to the sea, and, as in Babylonia, the canals, which were chiefly intended for irrigation, were used by cargo-boats. The upkeep of these canals and their sluices and the embankments by which they were contained like the Nile itself was ensured by the forced labour of those who dwelt on their banks.1 The Lagid government never neglected these works, which were indispensable to the economic welfare of the kingdom. The construction of the roads from various ports on the Red Sea to Coptos gave a great impetus to Nile-borne traffic between that city and the Delta. In the Delta itself shipping reached an intensity never known before. After mentioning the two outermost arms of the Nile, the Pelusiac on the east and the Canopic on the west, Strabo goes on:

"Between these two mouths there are many others, five of them large and the rest smaller; for the first two arms give off a great number of branches, which divide up the whole Delta, forming many streams and islands; and the whole of it is navigable, since connecting canals have been cut, which are so easily navigated that on some of them there are ferry-boats made of earthenware." 2

This development of river transport in the Delta was one consequence of the foundation of Alexandria, which soon attracted all goods to itself and was the point at which imports from abroad started for the interior.

To complete the system of waterways formed by the Nile and the canals disposed along it, the Ptolemies accomplished an undertaking which had been conceived by the Pharaohs and resumed by Darius, but for various reasons had never been finished—the construction of the canal connecting the Nile with the northern end of the Gulf of Heroöpolis, at the top of the Red Sea between Egypt and Sinai.

" Another canal," Strabo writes, " opens into the Indian Ocean, or rather the Red Sea, near the city of Arsinoë or Cleopatris, as it is sometimes called. It passes through the Bitter Lakes, which were once bitter, but when the canal was cut were changed by the admixture of water from the Nile, and are now full of fish and waterfowl. The canal was first cut by Sesostris, before the Trojan War, or, some say, by the son of Psammetichus, who was only able to begin it before he died, and subsequently by Darius I, resuming the task. He abandoned it when on the point of finishing it, under an erroneous impression; for he was persuaded that the level of the Indian Ocean was higher than Egypt, and that if the whole isthmus between them1 was cut through Egypt would be submerged by the sea. However, the Ptolemies cut right through, and made a closed passage, so that one could sail out to the sea or sail in again, when one wished, without difficulty." 2

To these general statements Diodoros adds a detail, namely that it was Ptolemy II Philadelphos who took on the completion of the work commenced by Necho and Darius. An Egyptian document discovered at Heroopolis, known as the Pithom Stele, tells us that it was finished between 280 and 264 B.C.3

This canal joined the Pelusiac Arm some distance below the point of the Delta, north of Heliopolis. By it, and the other canals which connected all the other branches, and the Canopos Canal, Alexandria could communicate with the Red Sea by water all the way. The Mediterranean was connected with the Indian Ocean, the Inner Sea with the Outer Sea, as they were called, not, as today, across the Isthmus of Suez, but bv the Nile and bv the Delta.

The importance assumed by land-routes and inland navigation in Hellenistic trade in no way diminished the marine activity which was so dear to the Greeks. Not only did their ships continue to range the Eastern Mediterranean; they ventured forth on the Indian Ocean. In the Eastern Mediterranean, regular lines of shipping grew up between Alexandria, the Phoenician ports, Rhodes, Delos, Corinth, Byzantion, and the Euxine. Westwards, the currents of trade ran chiefly towards Taras, Syracuse, Carthage, and certain points in central Italy and southern Gaul. On the Indian Ocean, the two chief directions followed by traffic, to Arabia Felix and to the Deccan, started from the east coast of Egypt and the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates respectively. The former first ran due south, to the strait of Deire (the present Bab el-Mandeb), and then, turning east, followed the southern coast of Arabia and that of Gedrosia to the mouths of the Indus.1 The latter went down the Persian Gulf from northwest to south-east and rejoined the former after passing the coast of Carmania. Lastly, Egyptian vessels were beginning to frequent the coasts of East Africa, visiting the Cinnamon Country, turning Spice Cape (Guardafui), and perhaps going some distance towards the Equator.

In the time of the Lagids and Seleucids, Mediterranean trade suffered from the scourge of piracy. The Euxine was infested with corsairs, Heniochi, Zygi, and Achseans, who came out from the rocky creeks dominated by the Caucasus,2 and Georgians of the Tauric Chersonese.3 A king of the Cimmerian Bosphorus named Eumelos made constant war on them for some years at the end of the fourth century. Diodoros doros says that he cleared the Euxine of these pirates and succeeded in protecting shipping;4 but Eumelos only reigned five years, and it is likely that piracy again broke out in those waters after his death. In the south of Asia Minor, the coast of Cilicia became, like that of the Caucasus, a regular lair of pirates, and not till Pompey and the Romans came was an end put to their activities.5 Yet other pirates, Cretans, Epeirots, and Illyrians, ranged the Mediterranean.

In spite of these dangers, the sea-routes played a very big part in Hellenistic commerce, and many ports on the Eastern Mediterranean attained a prosperity which they had not known before.

In old Greece, the chief centres of trade shifted eastwards, like economic life as a whole. For Athens and the Piræus, the days of active life and greatness were gone; they were approaching their death. Corinth alone, with its two ports, Lechæon on the Corinthian Gulf and Cenchreæ on the Saronic Gulf, and its position on the narrow isthmus between the Ionian and Ægean Seas, kept its old importance as an emporium or entrepôt of goods.1 The famous diolcos over which ships were dragged from one sea to the other was still in use.2 The capture and burning of the city by the Romans in 146 B.C. destroyed its prosperity, or rather interrupted it for a century. Corinth was revived by Julius Cæsar and Augustus, and under the Roman Empire it once more became a very busy trading port and entrepôt.

Delos was the chief gainer by the temporary eclipse of Corinth. Even before the disaster of 146, the holy island of Apollo was a port of call for most vessels proceeding from Italy or Greece to Asia.

" The religious gathering is something like a market, and people, especially Romans, were in the habit of going there even when Corinth was standing."3

On Delos lines of shipping from Egypt, Macedonia, and the West converged. Phoenicians, Egyptians, and Italians had counting-houses there and had founded societies which were at once religious brotherhoods and commercial clubs. The marine activity of Delos received an immense stimulus when the island was handed over by Rome to the Athenians, on the condition that they established a free port there. At that time the great port of the iEgean was Rhodes, which exacted duty on all goods entering or leaving the harbour. The creation of the free port of Delos gave the island commercial supremacy, at least for some time. Besides, " Delos offered every security to shipping and every convenience to trade. The anchorage was protected against the north wind by a strong breakwater. A mole divided it into two parts. On one side was the Sacred Harbour, intended for the caïques which carried the pilgrims; the landing-stage with which it was provided adjoined a big meeting-place of streets and an agora. On the other side was the Merchant Harbour, where the heavy cargo-boats came in. It was divided into portions, bounded by stones, and was fringed with wharves on to which warehouses and stores opened. . . . All around stretched the commercial quarter, with shops, workshops, bazaars. and hostelries all heaped together. . . . Delos, now become ' the common emporium of the Greeks,' collected all the products of Oriental Greece, from Egypt to the Euxine, in order to forward them to Italy. . . . She organized the uninterrupted passage of slaves, grain, spices, etc."1

On the Avest coast of Asia Minor, the first place, formerly held by Miletos, was now taken by Epliesos, which Strabo describes as " a general entrepot of the goods of Italy and Greece."2 The port of this city, however, had serious disadvantages, largely due to ill-conceived works undertaken by Attalos Philadelphos, King of Pergamon (159-138). The mud of the Cayster had silted up the old harbour. In 287 Lysimachos had dug a new one, more to the west. Attalos I'hiladenhos

" had imagined that the entrance to the harbour and the harbour itself would be deep enough for big vessels . . . if a mole were run across part of the entrance. . . . Exactly the opposite happened. Being kept inside the mole, the silt filled the harbour with shoals to the very mouth, whereas in the past the ebb and flow of the tide had to some extent carried the deposit away to sea. That is what the harbour is like; but, thanks to the other advantages of its situation, the city grows larger every day, and is the biggest commercial centre in Asia west of the Taurus."8

Ephesos stood at the end of the great road which ran over all Western Asia from Bactriana, India, and Iran.4 From the south another road came in, from Physcos, a port in the Rhodian Persea, by Lagin a, Alabanda, and Tralles.5

North of Ephesos, Smyrna, which was revived by Antigonos and Lysimachos, was a busy centre; so was Miletos, to the south, notwithstanding its decline; and still further south Cnidos had two harbours and a shipyard containing slips for twenty vessels.6

But during the Hellenistic period the commercial queen of the Ægean was for many years the city of Rhodes. Founded in 408 at the north-eastern end of the island, the city of Rhodes had soon eclipsed the three ancient cities of Lindos, Ialysos, and Camiros. Her prosperity had in no way suffered by the rule of the Queen of Caria, Artemisia II, nor by the events through which she had passed at the time of Alexander's campaign. " The state of Rhodes, favoured as it was by a most fortunate geographical position, had become extremely flourishing even in Alexander's lifetime, and still more so during the wars of the Successors. Almost all the trade between Europe and Asia concentrated on the island. The Rhodians were distinguished seamen, with a reputation for honesty and skill. Their strong, constant, law-abiding character, their knowledge of business, and their admirable marine and commercial laws made Rhodes a model among all the trading cities of the Mediterranean. By her continual and successful wars with the pirates, who at that time often disturbed the peace of the seas in great bands, Rhodes had become the protectress and refuge of merchant shipping in Eastern waters."1 Her chief trade was with Egypt, whence she received not only corn but also goods from Arabia and India, which she reconsigned to Greece and the West. It is possible that as early as the end of the fourth century she had entered into relations with Rome.2 At the time of the wars of the Successors, the aim of her policy had been to keep neutral; it was to defend this policy that she opposed Antigonos and his son Demetrios Poliorcetes in 305.3 The marine and commercial activity of Rhodes did not slacken for a century and a half; it only began to decline after 166, when the Athenians, at the instigation of Rome, made Delos a free port. All through the third century and the first half of the second, she ruled the Mediterranean, not only by the power of her fleet, by the extension of her trade as far west as the coasts of Gaul, Spain, and North Africa, and by her public and private opulence, but by her laws and regulations regarding marine matters.

" Her Jaws are admirable, and so are her institutions in general, especially in marine matters. . . . At Rhodes, as at Marseilles and Cyzicos, everything connected with the shipbuilding yards, war-engine factories, arsenals, etc., is treated with especial attention, and even more so than in the two other cities."4

It was chiefly to transit commerce that Rhodes owed her great wealth. All goods entering or leaving the port had to pay customs duty. It has been reckoned that the State raised a net sum of a million drachmas every year; this would mean a movement of goods worth about fifty millions, a very large sum for the time.1

Nothing can give a better idea of the place held by Rhodes in the economic life of the day than the effect produced on the whole of the Eastern Mediterranean by the catastrophe which befell her between 225 and 222 B.C. An earthquake destroyed the houses, city walls, and shipyards, and overthrew the famous Colossus. At once, princes and cities vied in generosity and eagerness to come to the rescue and help her to repair her ruins. Ptolemy III Euergetes sent 300 talents of silver, corn, building-timber, and material of all kinds; Antigonos of Macedon gave piles, beams, pitch, tar, and 100 talents of silver; Seleucos Callinicos, King of Syria, followed their example; and Prusias of Bithynia, Mithradates of Pontos, and Hieron of Syracuse distinguished themselves by the size of their gifts. Polybios, to whom we owe all this information, adds that it is practically impossible to enumerate all the cities which sent help to Rhodes in her misfortune.2 After recalling all these facts, Droysen concludes: "No doubt, Rhodes must have been one of the chief stations of the commerce of the world, since such sacrifices were made everywhere to preserve that one centre. But is that not sufficient proof that the commercial activity of Rhodes was not selfish or oppressive, but beneficent; that she was of vital importance to the states which gave her so much help? The prosperity of Rhodes bears witness to that of Mediterranean trade at the time."3 To these very just observations, we may add that perhaps the kings and cities of the Hellenistic world were becoming aware of an economic solidarity previously unknown. Neither the capture and destruction of Miletos by the Persians in 494 nor the fall of Athens in 404 had given rise to any such enthusiastic movement, in spite of the commercial importance of the two cities. Economic views seem to have become wider. The wealth and prosperity of a port like Rhodes inspired other feelings than envy. Their collective value was understood; they were not regarded as being her own affair entirely; when they were seriously damaged by a catastrophe, people wanted to help to restore them.

At the other end of the yEgean, on the Bosphorus, Byzantion had a geographical position to which it owed quite special advantages. It commanded the narrow passage connecting the Euxine with the Mediterranean. No ship could enter or leave the Euxine without its leave; in the vigorous phrase of Polybios, the people of Byzantion were thereby masters of all the things useful to human life which were produced by the Euxine.1 In 220 they wanted to make up for the tribute which they had to pay to the Celts settled in Thrace by levying a toll on all ships going through the Bosphorus. The Rhodians, whose predominant position in the shipping of the Ægean and Eastern Mediterranean we have seen, combated this claim, called upon the Byzantines to abandon the toll, and on their refusing declared war on them. Byzantion gave in, and undertook, in a formal treaty, to levy no toll on any ship entering or leaving the Euxine.2

In the interior of Asia Minor, two cities seem to have acted as entrepots or great regional markets: Pessinus in Galatia and Apameia on the Mseander in southern Phrygia. Pessinus owed its prosperity to the sanctuary of the Mother of the Gods, to which pilgrims came flocking. Even after the priests of the temple had lost part of their wealth and political power, the market of Pessinus continued to flourish as in the past.3 Apameia on the Mseander, or Apameia Cibotos, was, according to Strabo, one of the great centres of trade in the Roman province of Asia, second only to Ephesos.4 It benefited by its position on the great road which ran right through Western Asia from the Euphrates to the Ægean, at the point where that road left the high plateaus of central Anatolia and entered the rich valley of the Mæander.

Beyond Asia Minor, the most active centres of economic life stood either at the Mediterranean end of the great trade-routes from Asia and the unexplored regions north and northeast of the Euxine or in districts where the Hellenized East came into contact with the Indian Ocean, Arabia, and Iran.

At the top of Lake Mæotis, at the mouth of the River Tanaïs (the Don), the city of Tanaïs

" used to serve as a common market to the nomads of Europe and Asia and the Greeks of the Cimmerian Bosphorus, who sailed to it across Lake Mæotis. The former brought slaves, hides, and other things which nomads produce; the latter brought in exchange clothing, wine, and other products of civilized countries."1

At the eastern end of the Euxine, at the very foot of the Caucasus, Dioscurias presented the same character as Tanaïs. It was an emporium, where many peoples of the Caucasian isthmus and many tribes of the neighbouring regions met, most of them belonging to the ethnical body which the Greeks called the Sarmatians.2 South of Dioscurias, on the estuary of the Phasis, the colony of Pliasis was the centre of the trade of Colchis.3

On the Syrian coast, the great roads Irom the interior ended at Pierian Seleuceia, the port of Antioch. Founded by Seleucos I Nicator, who dug an artificial harbour, traces of which have been found, it was, in a sense, the capital and centre of the kingdom of Syria. It was, therefore, a bone of contention between the Lagids and the Seleucids. It was occupied by Ptolemy Euergetes in 245, and recovered by Antiochos the Great in 219. Its founder had chosen a good site for it, taking care not to set it right on the mouth of the Orontes, whose waters were laden with all the filth of Antioch.4 It stood at the foot of Mount Coryphaios, which dominated it on the north, on a site protected on the land side by steep slopes and a difficult valley, but open to the sea. It possessed warehouses  and stocks for the repair of ships

and stocks for the repair of ships  .5 " There was an inner basin, dug by human labour, oval in shape and surrounded by walls made of heavy blocks. It was connected by a short channel with the outer harbour, which was contained between two jetties. A complicated system of channels and dikes made it possible to divert the water of the mountain and to prevent silting."6 The port of Seleuccia was in Hellenistic times the principal outlet on the Mediterranean, not only of Syria properly so called, but of the country of the Euphrates and Tigris. The seaports of Phoenicia—Arados, Berytos, Sidon, Tyre—seem to have been reduced to a purely local or regional trade, fed by their own industries and the foodstuffs and manufactures of CœleSyria and Palestine, which came by the Jordan and the Lycos.1

.5 " There was an inner basin, dug by human labour, oval in shape and surrounded by walls made of heavy blocks. It was connected by a short channel with the outer harbour, which was contained between two jetties. A complicated system of channels and dikes made it possible to divert the water of the mountain and to prevent silting."6 The port of Seleuccia was in Hellenistic times the principal outlet on the Mediterranean, not only of Syria properly so called, but of the country of the Euphrates and Tigris. The seaports of Phoenicia—Arados, Berytos, Sidon, Tyre—seem to have been reduced to a purely local or regional trade, fed by their own industries and the foodstuffs and manufactures of CœleSyria and Palestine, which came by the Jordan and the Lycos.1

In the south of Mesopotamia, in Chaldæa and at the top of the Persian Gulf, several centres received goods coming from India, Iran, and Arabia, and sent them on to Syria and the Mediterranean. First there was, north-east of Babylon, Seleuceia on the Tigris, which was regarded as the commercial capital of the whole of Western Asia. Its foundation by Seleucos I and its rapid rise, thanks to the policy of the Seleucids, completed the ruin of the ancient Chaldæan capital.2 Then, in the region of the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates, there were two places about which Strabo, without giving their names, supplies the following information. On the banks of a huge lake, in which the Choaspes, descending from the mountains of Susiana, merged its waters in those of the Tigris, an entrepot had been established " for goods which, being unable to come up from the sea or to go down to it by the rivers on account of the artificial cataracts, are carried overland as far as this lake."3 Secondly, near the Euphrates, a big village served as an entrepot for goods coming from Arabia4 by sea or caravan.5

At the point where Palestine, Arabia, and the peninsula of Sinai meet, Petra, the capital of the Nabatæans, stood at the junction of several routes, by which the peoples of Arabia Felix, in particular those of Gerrha by the Persian Gulf and the Minseans of Yemen, brought snices to sell.6

The geographical position of Egypt between the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean, the fertility of its soil, the activity of its industries, and the very power and policy of its kings gave its new capital, Alexandria, a veritable economic sovereignty in all the Mediterranean world. Alexandria was the only Egyptian trade-port on the Mediterranean. It collected both the foodstuffs and manufactured goods of the Nile valley and the foodstuffs and raw materials which came from Ethiopia, East Africa, Arabia, and India, and distributed these all over the Greek world and into the West. Its population, in which Greeks, Egyptians, Jews, and Orientals mingled, already had that cosmopolitan appearance which stamps the great ports of the Levant today. The movement of business was remarkably intense.

The position which Alexander had chosen for the city made it possible to build a sea-harbour on the north and a river-harbour on the south. The sea-harbour, between the shore and the island of Pharos, protected from the eastern swell by Cape Lochias and the breakwater which ran out from it, was divided into two by the Heptastadion, a mole connecting Pharos with the land. On the east of the mole was the Great Harbour, the mouth of which was marked by day and lit by night by the famous Pharos tower which was the ancestor of the modern lighthouse. On the west was the Eunostos, which was more especially a merchant harbour, whereas the Great Harbour contained the royal dockyards and war-fleet. Two openings in the Heptastadion allowed vessels to pass from one harbour to the other. The Great Harbour was so deep that the biggest ships could come alongside the quay.

Important as the sea-harbour was, the river-port played quite as big a part in the business of the city. It stood on Lake Mareotis, and communicated by the many canals of the Delta with the Nile and the Red Sea. Now, Strabo tells us that more goods came to Alexandria by these canals than by sea, and the river-port soon became richer than the sea-port. The two were connected by a canal. The chief element in the trade of Alexandria was transit; it was truly the city where Mediterranean and Indian Ocean, Europe and Asia, West and East met.

No other city in Ptolemaic Egypt could compare with Alexandria for commercial activity. It would, however, be going too far to ignore the placcs where the products of Arabia, India, and East Africa arrived—Berenice and Myos Hormos on the Red Sea, and, above all, Coptos on the Nile.

" All goods from India and Arabia," Strabo writes, " and all Ethiopian goods which come by the Red Sea are taken to Coptos, and that city is the general entrepot of such merchandise."1

Coptos was connected by road with the Red Sea ports.2

So, from the northern shore of the Euxine to the lower valley of the Nile and from the Ægean to the south-western slopes of Iran, sea and river ports, entrepots and markets, were the busiest centres of national and international commerce. All these ports, entrepots, and markets had dealings with one another, and the goods which they received or sent out sometimes came from distant countries, of which the Greeks had scarcely heard. The commercial activity of Hellenistic times covered a very vast domain, much vaster than that of which the Greeks had obtained the mastery in the great days of their expansion and colonial power.

In these trading centres, these entrepôts and markets, and on the great routes by sea and land which covered the Eastern Mediterranean and all the neighbouring countries, quantities of goods of every kind were brought together, exchanged, and sent abroad.

The progress of city life, the creation of numerous towns, some of them populous capitals, like Alexandria in Egypt, Antioch in Syria, and Seleuceia on the Tigris, the diffusion of Hellenic manners in the East, and the tendency of the Greeks to look further afield—all these circumstances could not fail to give a great stimulus to retail trade. Recent excavations on Delos and on the site of Priene in Asia Minor, north of Miletos, have made it possible to reconstruct at least the material appearance, the setting of this local business. " Let us visit Delos. The streets are lined with shops, most of them quite small; on their fronts are the signs and symbols which advertise their wares; inside, the walls are full of niches. From the objects found on the spot we identify pottery-merchants, ironmongers, sellers of household articles, the ivory-turner, and the sculptor. Near the harbour the shops are grouped according to their special line. . . . Let us go on to Priene. The nearer we come to the markets, the more shops and little windowless workshops there are. Here is a meeting-place of streets—the Small Market. On all sides we see the bakers' shops. The marble tables with the water-channels along them are the butchers' and fishmongers' stalls. Further on is the square of the Great Market; there is a large altar in the middle, and the four sides are lined with spacious arcades, with rows of shops inside."1

If we allow lor differences due to local conditions, it must have been much the same in all the towns of Asia Minor, both the old Greek colonies of Miletos, Ephesos, Smyrna, Cyzicos, etc., and the new cities founded by the Successors, the various Laodieeias, Apameias, Seleuceias, and Antiochs. We may well imagine the business quarters of Antioch in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt as looking like the sukh of a big Levantine port of our own time. There men must have sold, not only the food and other things needed for daily life, but a variety of objects, many of them rare and exotic, intended to satisfy the tastes of well-to-do customers or to tickle the fancy of passing travellers.

The sanctuaries were sometimes also entrepôts and markets. We have seen above2 that Pessinus was one of the chief trading centres of Galatia and that it owed its prosperity to the famous sanctuary of Cybele. The Egyptian temples were surrounded by shops and hostelries.3 On the days of pilgrimages and great religious festivals, when pilgrims came pouring in, who had to be fed and wanted to take some memento, talisman, or fetish away with them, this particular form of local retail trade became unusually active.

But, whatever may have been the difference between the true Greek period and the Hellenistic period in respect of the intensity of this local business, it was chiefly in operations on a big scale, export, import, and transit, that the business of the Hellenic world was transformed, or rather took on a new life.

On the Eastern Mediterranean, an active movement of goods—foodstuffs, raw materials, manufactures—flowed from the coasts of Egypt and Asia to European Greece and the West. Some of these goods were produced in the countries which sent them; others had come from further away, and only passed through. Alexandria exported corn, textiles, and paper produced by Egyptian agriculture and industry; it also sent the spices of Arabia and India all over the Mediterranean world. The Phœnician ports distributed purple dyed textiles, Sidonian glassware, and timber from Lebanon in all directions; and from their harbours, as from those of Pierian Seleuceia, ships sailed laden with all the goods which the caravans had brought from the countries of the Euphrates and Tigris, Susiana, Persia, and the depths of Asia— perfumes, ivory, precious stones, and silk tissue. From Cyprus copper and wood went to distant markets. Asia Minor supplied the countries of the Mediterranean seaboard with celebrated wools, the saffron and timber of Cilicia, the famous wines, parchment, bronzes, and stuffs, woven or plated with gold, of Pergamon, and the iron of the country of the Chalybes; it also sent, like Syria, everything which came down to the ports of Ionia, especially Ephesos, by the great road which ran from India and Bactriana by the Caspian Gates and Samosata. From the Euxine came livestock, salted goods, honey, wax, furs, and corn.1 Colchis exported linens which competed with those of Egypt.2

It was not only with the Mediterranean and the West that the Hellenistic world maintained active trade relations. The merchants and shipowners of the Hellenized East did not wait for the Asiatic and African goods which they consigned from Alexandria, Seleuceia, Ephesos, Tanaïs, and Byzantion to be brought from the producing country by native shippers; they went to get them by land and by sea, and in exchange they introduced goods produced in the Mediterranean regions. Thus it was that Greek merchants went to India, either by the route along the northern slopes of the Iranian plateau or by the Persian Gulf (or the Red Sea) and the Indian Ocean. Others worked the ports of Arabia Felix and explored the coast of East Africa in the neighbourhood of Spice Cape (Guardafui). In one region or the other they obtained spices, perfumes, ivory, tortoiseshell, precious woods, pearls, and silk; they took to them wheat, wine, textiles, metals, weapons, glassware, and slaves. They also left a great number of gold and silver coins behind them,3 for they bought far more than they sold on all these distant markets. Strabo even declares that the people of Arabia Felix were said to have amassed enormous wealth by exchanging their perfumes and precious stones for the gold and silver of other nations and never spending or exporting any of it.1

In addition, at the meeting-points of the Hellenistic world and the regions outside, certain peoples acted as middlemen. Such were the nomads of Europe and Asia2 who met the Greeks of the Cimmerian Bosphorus on the market of Tanai's; the Armenians who traded with the Scythians beyond the Caucasus, with Central Asia, India, and China in the east, and with Babylon and Cappadocia in the south and west;3 or, again, the Arabian Scenitæ who controlled the desert country stretching from the Euphrates to Palestine and Syria;4 or, yet again, the Nabatæans who dwelt in the wilderness near the east shore of the Red Sea.5

In respect of trade, therefore, the Hellenistic world must not be regarded as a limited, independent, self-sufficient area. It formed a vast region which faced two ways. It was not a barrier between the Mediterranean basin and the distant and formerly almost unknown and unexplored countries of Ethiopia, Arabia, India, and Central Asia. On the contrary, it maintained communications and economic relations between those two vast zones of different and complementary production. Transit had quite as big a place in economic life as importation and exportation.

The rulers of the kingdoms which sprang from the dissolution of Alexander's empire and a number of Greek cities perceived the profit to be obtained from this situation. No doubt, before the conquest of Asia, customs duties had already been established by certain cities in Greece Proper;6 but no one had anywhere conceived a complete system of fiscal measures to compare with that with which, for instance, the trade of Egypt was burdened. " There was a net of customs posts," writes Bouché-Leclercq, " drawn tight round all the frontiers of Egypt."7 Strabo had already remarked on the working of these Egyptian custom-houses.

" The most valuable consignments come from these countries" (India and Ethiopia) " to Egypt, and are sent on from there to the rest of the world, so that Egypt gets double duties from them, on coming in and on going out; and the duty is heavy in proportion to the value of the goods."1

On the Red Sea, the Egyptian customs no doubt operated in the ports of Berenice and Myos Hormos; in the south, on the Nile, there was a post at Syene; in the north, in the Delta, the most important custom-house was of course at Alexandria, and there were others on the various mouths of the river, at Pelusion, Sebennytos, and Naucratis. The duty on all imports was 25 per cent, of the value; we do not know the export tariff.2

This duty on imports and exports was not the only burden laid on goods transported through Egypt. They were subject to a fee for the right to be carried on the roads and canals, and travellers had to pay a similar tax.3 We know of two toll-houses on the Nile for the barges using the river, at Hermopolis, near the administrative boundary between the Thebaid and the Heptanomis, and at Schedia near Alexandria.4 At the gates of towns, and even of villages, goods had to pay duty on going in or out, comparable to the French octroi. At Syene, at Thebes, and at the small town of Socnopseu Nesos in the Fayum the duty on outgoing goods was 2 per cent.5 At Syene and Memphis there was a harbour or wharf duty,6 Local trade was burdened just as much as big trade. It is not certain that merchants had to take out a trading-licence, but at least they paid for the right to a place on the market.7 They were also subject to a tax on sales, which seems to have amounted to a fiftieth.8

In Egypt, then, there was not a single stage on the way by which goods went either from a harbour of import to a harbour of export or from a place of production to a place of consumption, where the exchequer did not step in and seize some proportion of the value of the goods.

The interference of the Lagid sovereigns also took another form, which is perhaps more characteristic—the monopoly of certain sales, the monopoly of importation and exportation of certain products. As far as we can tell from the documents, this twofold monopoly applied to salt, nitre or natron, precious stones and ivory, perfumes and spices, wine, oil, papyrus, textiles, and perhaps wheat.1

This economic organization of Egypt cannot be explained solely by economic causes or by financial necessities. It is hard to suppose that any protectionist notion underlay the creation of import and export duties on things which Egypt did not itself produce, such as ivory, perfumes, and spices. On the other hand, the rate of these duties would be quite exorbitant, if the Egyptian government had only wanted to recover the costs of the original establishment and the upkeep of the harbours, roads, and canals. The chief, underlying reason of the whole system must be sought in the character of the Ptolemaic kingship, as the heir of the monarchy of the Pharaohs. The sovereign owned all the resources of the country; just as he was, in theory, the sole owner of the soil and absolute master of the human beings who lived on it, so he had the free disposal of everything manufactured by the labour of his subjects, and every commercial transaction—all importation, all exportation, all transit, every sale inside and outside Egypt—was his affair, and the profits should be paid into his treasury. This is another form of the State control of economic matters which we have already seen in the case of agriculture and industry. The roots of that system lay deep in the past of the ancient East, and its tyranny was maintained the more strictly because it was supposed to be justified by the divine nature of the King. The commercial taxation of Egypt seems to me to have the same origin as the land-tax and the organization of agricultural property, the monopolies of manufacture, the taxes on the trades, and the detailed regulations governing industry. Monopolies, taxes, licences, and the rest were simply the various institutions expressing and enforcing the eminent ownership which the King claimed over all nature and all human activity.

While we have fairly detailed and accurate knowledge of the conditions to which trade was subiect in Egypt. we have far less information about its organization in the other Hellenistic kingdoms—Syria, Pergamon, Bithynia, Pontos, Cappadocia, Macedonia. We know that in many Greek cities and districts there were customs duties, tolls on traffic, and taxes on certain sales,1 but as a rule we know nothing of their true character. Nevertheless, some very interesting details are given by the ancient authors, by Polybios in particular, about the duties set up by Rhodes and Byzantion.

Rhodes, as we have seen, had become far the most important port of call between the kingdoms of the Orient and the old Greece. Ships from Alexandria, the Phœnician and Syrian ports, and Cyprus stopped there. On every vessel entering their harbour the Rhodians imposed a tax which Polybios calls ellimenion, which was doubtless a harbour-due. This tax yielded as much as a million drachmas (rather less than £40,000). When the Romans began to take a predominant place in the Eastern Mediterranean, in 166, after the battle of Pydna, they gave the island of Delos to the Athenians, on condition that it should be a free port. From then onwards the port of Rhodes was abandoned, the yield of the harbour-tax fell to 150,000 drachmas, and the Rhodians sent an embassy to Rome to complain to the Senate.2 This Rhodian tax was neither a customs duty nor an octroi. It was not laid on goods entering or leaving the town or island, but on ships which called at the port. It represented, in Polybios's words, the revenue of the port,

. In setting up this tax, the people of Rhodes had acted as a landlord trying to get a profit from his estate. The ellimenion was based on the eminent right of ownership which the Rhodians claimed over the actual water of their harbour. Goods which came on to that water, not to be unloaded but merely to remain on it a few days or even a few hours, were taxed, just as the goods which went across Egypt from Myos Hormos, Berenice, or Coptos to Alexandria had to pay import duties, traffic tolls, and export duties, in virtue of a wholly Oriental conception of the sovereignty of the State in every matter and over every thing. The delegate who was sent to Rome by the Rhodians made a point of the fact that his fellow-countrymen had lost the liberty which they had formerly had of themselves settling questions regarding their port.1

. In setting up this tax, the people of Rhodes had acted as a landlord trying to get a profit from his estate. The ellimenion was based on the eminent right of ownership which the Rhodians claimed over the actual water of their harbour. Goods which came on to that water, not to be unloaded but merely to remain on it a few days or even a few hours, were taxed, just as the goods which went across Egypt from Myos Hormos, Berenice, or Coptos to Alexandria had to pay import duties, traffic tolls, and export duties, in virtue of a wholly Oriental conception of the sovereignty of the State in every matter and over every thing. The delegate who was sent to Rome by the Rhodians made a point of the fact that his fellow-countrymen had lost the liberty which they had formerly had of themselves settling questions regarding their port.1

The case of Byzantion is no less instructive. About 220-219 B.C., being compelled to pay heavy tribute either to the Gaids or to the Thracians, after vainly calling on the other Greek states for help and support, the Byzantines instituted a toll on all ships going from the l'ropontis to the Euxine or vice versa. In this way they hoped to obtain resources with which to pay the tribute. The shipowners and merchants who traded with the countries on the Euxine protested against the tax. Rhodes took charge of the movement. When Byzantion refused to give in, there was a war, in which, in addition to Rhodes and Byzantion, Prusias, King of Bithynia, certain Thracian contingents, and the pretender Achæos, who had rebelled against the King of Syria, played a greater or less part. Byzantion was defeated, and had to abolish the tax.2 What right could she invoke in favour of its institution? It was not the consequence or expression of a legal sovereignty, like that of Ptolemy as successor of the Pharaohs in Egypt ot that of the Rhodian people over its harbour, which was regarded as an integral part of the domain of the State. The mastery exercised by Byzantion over shipping on the Bosphorus was simply a fact, which Polybios recognizes and describes in forcibly definite language: " Byzantion so controls the mouth of the Euxine  that no merchant can enter or leave that sea without her leave." Further on, the historian adds that trade with the Euxine would have been almost impossible if Byzantion had joined forces either with the Gauls or with the Thracians, for, he says, the Bosphorus being so narrow and the barbarians so near, the Euxine would have been unapproachable to the Greeks.3 Whether Byzantion had a sovereignty by right or a mere mastery in fact, it is none the less clear that the reason for the taxes levied on various commercial operations in the Hellenistic period were much more of a political than of an economic or financial nature. By the collection of these taxes the notion of the sovereign State, that legacy of the ancient East, was expressed and manifested at every moment.

that no merchant can enter or leave that sea without her leave." Further on, the historian adds that trade with the Euxine would have been almost impossible if Byzantion had joined forces either with the Gauls or with the Thracians, for, he says, the Bosphorus being so narrow and the barbarians so near, the Euxine would have been unapproachable to the Greeks.3 Whether Byzantion had a sovereignty by right or a mere mastery in fact, it is none the less clear that the reason for the taxes levied on various commercial operations in the Hellenistic period were much more of a political than of an economic or financial nature. By the collection of these taxes the notion of the sovereign State, that legacy of the ancient East, was expressed and manifested at every moment.

Such a vast and complex system of commercial exchanges, on the top of which there was in the monarchical states and in many cities a fiscal control which was often meticulous and exorbitant, could not have developed and lasted if purchases, sales, and payments had not been conducted by simple, easy methods.

No doubt, in many parts of the East, and particularly in Egypt, debtors continued to make payments in kind, which were accepted by their creditors, and by the State in particular.1 Perhaps, too, in dealings with the peoples of India, Central Asia, and Arabia, with the nomadic Sarmatians who ranged the steppes north of the Caucasus, and with the tribes which dwelt on the east coast of Africa, simple barter was often practised. The Sabaeans, who accumulated masses of gold and silver coin without buying anything from their customers, were certainly an exception. Nevertheless, the practice of settling accounts in hard cash or by banking operations became general in the Hellenistic world.

this increasing supremacy of monetary economy over natural economy was encouraged by various causes, the most important of which were the great increase of the amount of precious metal given over to minting and the institution, if not of a single currency, at least of a number of currencies so closely related that one could pass from one to the other without serious inconvenience.

In Greece, the gold and silver mines of Siphnos were already exhausted, and the mines of argentiferous lead at the Laureion now yielded very little; but the veins of precious metal on Mount Pangaeos, on the borders of Macedon and Thrace, which even in the reign of Philip, Alexander's father, had produced a thousand talents a year, made it possible for the Kings of Macedon to issue large quantities of coin. But the great difference was made by the treasures of the Acheemenids, which Alexander seized at Susa, Persepolis, and Ecbatana, where there were enormous masses of gold and silver bullion.2

Polybios gives us a very curious piece of information on the subject. In his description of the royal palace at Ecbatana, he tells us that the beams and panelling and the columns of the porticoes and peristyles were plated with gold and silver and that all the tiles were of silver.

" Most of these plates and tiles were removed at the time of the invasion of Alexander and the Macedonians, and the rest when Antigonos and Seleucos seized the power. In the reign of Antioclios, the gold was still on the columns of the temple of the goddess Æna, and silver tiles were heaped up in it in great numbers, and it still contained a few blocks of gold and many of silver. All these riches were used for making coins, on which the royal effigy is stamped, to a value of about four thousand talents."1

Later, as trade became intense, the Seleucids, Attalids, and Kings of Pontos and Bithynia were able to obtain gold from Colchis, the Caucasus, the Ural country, Armenia, Bactriana, India, and Arabia.2 In Egypt itself, the Ptolemies worked rich gold-mines situated in the Arabian Desert.3 Apart from gold and silver, the mines of Cyprus yielded copper, and trade with the Far East or parts of Iran supplied kings and cities with tin, the two metals needed for making bronze coins. The circulation of metal became general.

That it might not encounter almost insurmountable obstacles, it was necessary that the coins struck by the various states and cities should not belong to systems which were too different from one another, at least as far as gold and silver were concerned, copper and bronze coinages being usually current only in the country where they were issued.

At the time when Alexander conquered the East, the monetary standard adopted by most Greek cities was the Attic standard, the drachma of 4.25 grammes, and the most widely distributed coin was the Attic silver tetradrachm, or four-drachma piece. Alexander made his monetary system fit the Attic standard. Tetradrachms of Attic weight with the effigy of Alexander were struck in most Greek cities down to the Roman conquest in Europe and in Asia.4 The Attic standard was likewise adopted by the Seleucids.

When Rhodes obtained the commercial supremacy which we have already noted, she caused a system based on a rather different standard to be accepted—that of the so-called Asiatic drachma, doubtless invented in Asia Minor, weighing 3.25 grammes. The drachmas, didrachms, and tetradrachms of the Rhodian system circulated for about two centuries from East to West. On the obverse they bore the radiate head of Helios, the great god of the island and city of Rhodes, and on the reverse a rose (rhodon), the symbol of the state.1 To the same system belonged the famous cistophori, which were so popular all over Asia Minor from the beginning of the second century B.C.2 These coins were tetradrachms, and got their name from the Dionysiac chest (kiste) which adorned the obverse.3

In Egypt, when the Ptolemies organized the first monetary system which the country had known and when they substituted their own effigies for that of Alexander, they adopted neither the Attic nor the " Asiatic" standard, but the Phœnician standard, the silverdrachma of 3.5 or 3.54grammes. In this system the silver tetradrachm was the coin in most general use.

There were, then, no fundamental differences between the three or four chief monetary systems used in the Hellenistic East. Attic tetradrachms stamped with the owl, tetradrachms with the image of Zeus Aetophoros on the reverse, Rhodian tetradrachms, cistophori of Asia Minor, and Egyptian tetradrachms represented fairly similar weights of metal and values. While we may grant that a man would not take one of these coins instead of another, the trapezitai, or moneychangers, had not to make very involved calculations for their operations. Twenty Rhodian tetradrachms or twenty cistophori were almost exactly equal to fifteen Attic tetradrachms, and twenty Egyptian tetradrachms to sixteen Attic tetradrachms. That was no serious obstacle to commercial transactions.

Some men seem to have gone further, and to have dreamed of creating a true unity of weights, measures, and coinage. The only instance which we know of an attempt of the kind referred, it is true, to a very limited area, but it is significant all the same. Polybios relates that about the year 220 the Achæans succeeded in establishing this unity in the Pelo ponnese.4

When business developed and trade was done or could be done between regions as far apart as the Euxine, the ports of Syria and Phoenicia, Alexandria, and Great Greece, a comparatively single or similar coinage did not suffice to solve the problem of exchanges. The organization of credit, the action of banks, and the circulation of paper money, which had already appeared in Greek business before the time of Alexander, spread and developed. In many Greek cities, especially in the islands of the Ægean, in Asia Minor, and in Egypt, there were public banks and private banks, which received deposits, usually in specie but sometimes also (as in Egypt) in kind, established veritable current accounts for their clients, issued letters of credit, and effected transfers from one account to another. The use of the cheque became more and more general. Every bank had correspondents in other cities and other countries. All the credit transactions effected by the banks gave a great impetus to commercial operations. There was constant action and reaction; the progress of trade led to the development of credit, and the development of credit contributed effectively to the progress of trade.

Other features characteristic of big business began to take shape. Commercial companies were founded; merchants or banks combined for commercial or financial undertakings which required much capital. In one place the law of competition was evaded by the coalition of the producers or sellers; in another, to raise the price of a commodity, the papyrus of Egypt or the balsam of Judæa,1 production was limited; elsewhere again, regular corners were effected, which gave a single man the control of the market and a practical monopoly of the sale of the goods in question.2

So, during the Hellenistic period, as a result of the work accomplished by Alexander and his successors, economic activity became a very big thing in the Eastern Mediterranean.

The area over which it was practised was very great; it grew up chiefly in Asia and parts of East Africa. Egypt, Syria, Chaldæa, and certain valleys in Asia Minor were among the most fertile districts in the ancient world. Raw materials, old ones coming in greater quantities or entirely new ones, contributed to the rise of manufactures. Trade, both between the various regions of the Hellenized East and between that East and distant parts of Asia, Africa, and Western Europe, enjoyed a geographical extension and an intensity which it had not known before.

Before Alexander's expedition, the Eastern Mediterranean had been for Greek economic enterprise a blind alley, jealously guarded by the Egyptians, Phoenicians, and Persians. After the expedition, that enterprise found the road lying wide open to the markets of Central Asia, India, Arabia, and the east coast of Africa.

In that greatly enlarged field of action, the Greek genius was able to display its intelligent activity and the spirit of initiative which had long ago been awakened by political liberty and was guided by what was now old experience. The contribution of the East to the organization of the new economic life seems to have been the action and share which the kings claimed in all kinds of production and commerce. The Lagid like the Pharaoh and the Seleucid and Attalid like the Achaemenid were in theory the lords of everything, living and inanimate, in their kingdom. The earth, with its harvests, its trees, its grass-land, and its mineral wealth, belonged to the King, and it was for him that men laboured, manufactured, shipped, and sold. In proportions which varied from one country to another, the King kept for his own immediate profit a part of the soil, industry, and traffic; over the remainder, which he consented to leave to his subjects, his eminent right of ownership was expressed by duties and taxes of various kinds, many of them very burdensome. It was in the Oriental monarchies that economic nationalization had its birth, as a logical consequence of the divine nature ascribed to the King.

While all round the Eastern Mediterranean and in the regions of Asia nearest to that sea, this new economic life was developing, having at once something of the old methods practised in independent Greece and something of those characteristic of the states of the ancient East, the West, after long remaining barbarous or isolated, was opening more and more to influences of every kind from the East. Its economic life was developing. After first being subjected to the influence of Greece and the East, presently, as the political power of Rome dominated and then absorbed the other states, it would contribute to the establishment of the unity of the Mediterranean world in the special domain of economic facts.

Notes

and stocks for the repair of ships

and stocks for the repair of ships  .5 " There was an inner basin, dug by human labour, oval in shape and surrounded by walls made of heavy blocks. It was connected by a short channel with the outer harbour, which was contained between two jetties. A complicated system of channels and dikes made it possible to divert the water of the mountain and to prevent silting."6 The port of Seleuccia was in Hellenistic times the principal outlet on the Mediterranean, not only of Syria properly so called, but of the country of the Euphrates and Tigris. The seaports of Phoenicia—Arados, Berytos, Sidon, Tyre—seem to have been reduced to a purely local or regional trade, fed by their own industries and the foodstuffs and manufactures of CœleSyria and Palestine, which came by the Jordan and the Lycos.1

.5 " There was an inner basin, dug by human labour, oval in shape and surrounded by walls made of heavy blocks. It was connected by a short channel with the outer harbour, which was contained between two jetties. A complicated system of channels and dikes made it possible to divert the water of the mountain and to prevent silting."6 The port of Seleuccia was in Hellenistic times the principal outlet on the Mediterranean, not only of Syria properly so called, but of the country of the Euphrates and Tigris. The seaports of Phoenicia—Arados, Berytos, Sidon, Tyre—seem to have been reduced to a purely local or regional trade, fed by their own industries and the foodstuffs and manufactures of CœleSyria and Palestine, which came by the Jordan and the Lycos.1

that no merchant can enter or leave that sea without her leave." Further on, the historian adds that trade with the Euxine would have been almost impossible if Byzantion had joined forces either with the Gauls or with the Thracians, for, he says, the Bosphorus being so narrow and the barbarians so near, the Euxine would have been unapproachable to the Greeks.

that no merchant can enter or leave that sea without her leave." Further on, the historian adds that trade with the Euxine would have been almost impossible if Byzantion had joined forces either with the Gauls or with the Thracians, for, he says, the Bosphorus being so narrow and the barbarians so near, the Euxine would have been unapproachable to the Greeks.