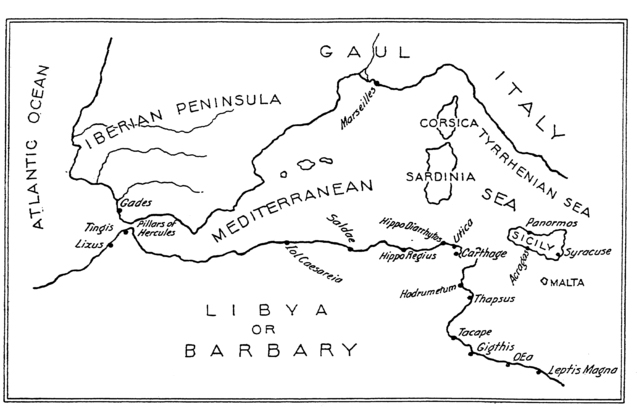

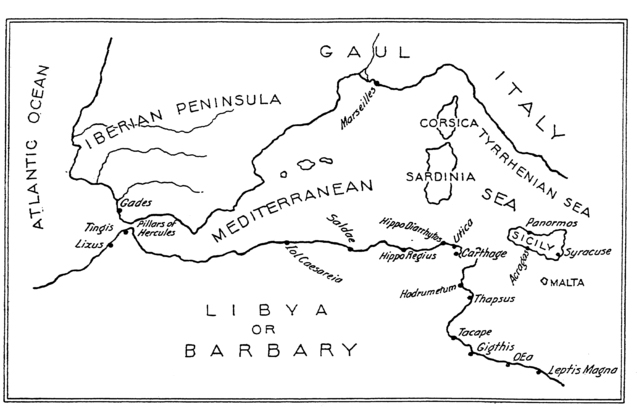

MAP IV.—THE CARTHAGINIAN EMPIRE.

THE economic life of North Africa, from the Greater Syrtis to the Atlantic, remained stationary much longer than that of Western Europe. The influence of the Ægean civilization does not seem to have made itself felt here. The pioneers of progress were first the Phœnician mariners and then Carthage.

At the time when the sailors of Tyre, and Sidon were establishing their first ports of call on the north coast of Barbary, the peoples then inhabiting the country had not advanced beyond the civilization of the Stone Age, being still at the Neolithic stage. The most ancient metal objects used by them were probably brought from abroad by sea.

Although our information about the beginnings of agriculture in North Africa is very meagre and very vague, we may suppose that, at least in some parts, wheat, barley, and some vegetables, including the bean, were grown before any Phoenician influence appeared. In any case, stock-breeding already had an important place in economic life; oxen, sheep, goats, and horses were domesticated. They had perhaps come from the East, from Egypt.2

According to the most probable reckoning, it was in the twelfth century B.C. that the first Phœnician ships appeared in the waters of the Western Mediterranean. They needed ports of call along the African coast, on the way to the Spanish mining districts, and these ports, where the earliest traffic with the natives doubtless began, subsequently became permanent "factories," real colonies. According to tradition, the earliest Phœnician settlements were, from east to west, Leptis Magna (Lebda), Hadrumetum (Susa), Utica, Hippo Diarrhytos (Bizerta), and Hippo Regius (Bona), and at this time, beyond the Pillars of Hercules, Lixus was founded (near Larash, south of Tangiers). Meanwhile, the Tyrians and Sidonians established themselves on Malta, at the southern point of Sicily, in Sardinia, and at Gades in Spain.

Carthage was founded about two hundred years after these beginnings of Phœnician colonization in the West; one may safely say that it was at the end of the ninth century.1 She rapidly became the most prosperous and powerful of all these colonies. When Tyre had been first weakened and then ruined by the despotic rule of the Kings of Assyria, Chaldæa, and Persia, Carthage took upon herself the protection of the Phœnicians against their rivals, the Greeks, all over the West, and became the capital of a veritable empire of a marine and commercial kind. At the beginning of the fifth century, her supremacy was recognized, willingly or otherwise, by the settlements which Tyre and Sidon had founded in the Western Mediterranean and along the Atlantic coasts northward and southward from the Pillars of Hercules. Her sway extended over western Sicily, Sardinia, the Balearic Isles, the west coast of Iberia, and all North Africa as far as the west of Cyrenaica.

In Africa, not content with imposing her authority on the coast-towns, she annexed a fairly large territory in the interior. Although the exact boundaries of that territory are not known, historians are agreed that it comprised the north and most of the centre of the present Tunisia. This was the starting-point and base of an influence which cannot be disputed. "Carthage," writes M. Gsell, "already a great Mediterranean port and the capital of a vast sea-empire, now became an African capital as well. She spread her civilization in the country which she annexed, and then beyond her own territory, among her vassals and allies."2 The influence which she could then exercise was not only political; it contributed to the progressive transformation of the economic life of North Africa.

To whatever extent the earlier populations of North Africa may have grown certain crops and raised livestock, it was only after the constitution of the Carthaginian Empire that the country really became acquainted with agriculture, that the various resources of the soil were exploited scientifically and methodically, that a serious effort was made to cultivate its vegetable and animal wealth. No doubt, that rural economy was only applied to a fairly small area, the territory directly subject to Carthage and the immediate neighbourhood of the Phœnician and Punic colonies dotted along the coast. Not until the Roman period would North Africa become one of the granaries of the Mediterranean world. None the less, Carthage inspired the first progress made by the Berbers in agriculture and stock-breeding.

The most abundant cereals continued to be, as in prehistoric times, wheat and barley; we cannot say what varieties predominated. The Phœnicians introduced fruit-growing into the country. The soil and climate were favourable to the vine, the olive, the fig, the almond, and the pomegranate, and it is possible that all these had long grown there in a wild state. Probably the arts of pruning and grafting, the special treatment required by each species, and methodical planting in ground suitably situated and prepared were now introduced. The earliest African orchards date from the time of Carthaginian rule. The exploitation of the date-palm can only have interested Carthage in the few oases scattered along the coast of the Syrtes. Round the cities, the vegetables needed to feed town populations were grown in large quantities.

Stock-raising, too, was greatly improved. The Carthaginians possessed a cavalry which, if not very big, was at least very well looked after. The grass-lands over which the army of Agathocles went in 310 were full of horses. Nor was there any lack of mules. Most of the races of domesticable animals known to the ancients were represented in Libya.

"In that country," Polybios says, "there is such abundance of horses, oxen, sheep, and goats, that I do not think anything like it could be found in all the rest of the world."1

One of the Carthaginian sacrifice-tariffs now known enumerates, as victims due to the deity, calves, rams, sheep, he-goats, lambs, and kids.1 Poultry-keeping and bee-keeping were equally prosperous. Punic wax was especially renowned.

This agricultural and pastoral wealth was due, not only to the nature of the soil and climatic conditions, but to a serious study of the subject. In this respect, the economic practice of Carthage was at an early date, if not exactly scientific, at least reasoned and thoughtful. The Greeks and Romans knew and quoted authors who had written of agriculture and stock-breeding in the Punic language. The most famous of these writers was Mago, whose treatise in twenty-eight books was translated into Greek and Latin. Varro, Columella, and Pliny the Elder often refer to it. Mago did not merely deal with the treatment of plants, trees, and livestock; he touched upon every matter covered by farming. If we possessed his work, we should find valuable information about the implements and methods used in the agriculture and stock-farming of Punic Africa. What we know of it comes to very little. The plough used was simply the old implement without a fore-carriage, with a triangular iron share. The grain was separated from the straw either by being trodden by animals or by means of threshers of various types. Ingathered crops were stored in siloes. We do not know how the Carthaginians made wine, but it seems certain that they made plenty of it, and perhaps they even clarified it with gypsum. We do not know how they extracted oil from olives; no details have come down to us about the shape or working of their presses. But, although there are great gaps in our knowledge of Punic agricultural lore, it is at least certain that it was highly developed, and constituted "a true science, of which there were very learned teachers and very keen students among the aristocracy" of Carthage.2

To sum up, "the Carthaginians devoted themselves to agriculture with success. . . . By the exploitation of their possessions and by the influence which their example had on the natives, they contributed greatly to the foundation of the material prosperity which Africa would enjoy under Roman rule."3

About the organization of rural property in the Carthaginian Empire, our information is fragmentary. Did the State keep land for itself and work it direct? Did the estates held by the citizens of Carthage belong to them entirely, or were they burdened with taxes asserting the eminent ownership of the State? These are questions which cannot be answered, for lack of evidence. We only know that the territories conquered by Carthage in Africa, western Sicily, and Sardinia and left in the hands of the subject peoples had to pay rent in kind and tribute in specie, both of which obligations bore witness to their legal status.

Slave labour was extensively used by the Carthaginian nobles for the cultivation of the land round their villas and the keeping of their livestock. In special circumstances, for the corn-harvest, hay-making, vintage, and olive-picking, they made use of agricultural labourers who may have been nomads from the parts of Africa which Carthage had not conquered. Small landowners and natives of the territory who had become the subjects of the victorious city tilled their land themselves. Carthaginian farming, therefore, included various methods, suited to the various forms of ownership and the natural conditions of the countries of which the Empire was composed.

Did this farming bring Carthage great wealth? It seems to have been about sufficient for the needs of the State and individuals, but not to have furnished much for exportation.

We do not know what part hunting played in Carthaginian life. Sea-fishing was practised on the coasts of the Syrtes and near Carthage, and also in the Atlantic, south of the Pillars of Hercules. In these latter waters the fishing-boats stayed out for some time, for the tunnies caught were salted on board.

While agriculture and stock-breeding were practised, at least in a rudimentary form, in North Africa before the coming of the Phœnicians and the foundation of Carthage, industry was only established and developed by the newcomers and under their influence. One may reasonably suppose that that activity and influence were chiefly, if not wholly, confined to the urban centres.

The seeking and exploitation of the raw materials which the soil of Barbary might contain do not seem to have been pushed forward very actively so long as Carthage was independent. Building-materials were doubtless sought in the stone-quarries near the bigger towns,1 and the forests of the country supplied the wood used in many industries. But we have no evidence strong enough to justify the supposition that the metallic resources of North Africa, the lead, copper, and iron mines now known in various parts of the country, were turned to account.2 Like tin, these ores or metals were imported from the Peninsula or even further. Gold came from Central Africa, either by sea along the Atlantic coast or overland across the Sahara.

In every urban agglomeration, especially in a big town like Carthage, many industries which are indispensable to all collective and social life inevitably grew up, those of building, wood and stone, spinning and weaving, leather, furniture, and food. There is nothing peculiarly Punic in all this. We need only dwell on those industries which throve most at Carthage and in her colonies and shed a light on the special characteristics of Carthaginian industry.

The greatness of Carthage was based on her sea power, both commercial and military. Shipbuilding was therefore important, being conducted partly by private yards and partly by the State. Polybios tells us that the Carthaginians were very expert in this industry. They obtained wood from Africa and esparto for ropes from Spain. The improvement of harbours and the organization of special yards and workshops developed alone with the progress of shipping.

The metal industries first arose in Barbary under Carthaginian rule. The Punic inscriptions mention iron-founders, copper - founders, and manufacturers of various utensils. The Punic cemeteries have yielded, in addition to some weapons, such as swords, daggers, and heads of spears, javelins, and arrows of iron or bronze, numbers of tools and implements: axes, hammers, knives, shears, scrapers, hooks, bells, mirrors, and little shovels, some of bronze and others of iron; copper blades of a ritual character, which some take for razors and others for small axes; bronze vessels, such as ewers, scent-pans, dishes, cups, bottles; and a few articles of lead. The metals were also used for adorning wooden chests and boxes, which were given handles and other fittings of bronze or lead.1

Equal use was made of the precious metals. The goldsmith and jeweller used gold and silver for decorating sanctuaries, in which we hear of crowns, tabernacles, and plates of gold; for supplying the rich with table-services, bowls, vases, and sometimes even shields, of gold or more often of silver;2 or for satisfying the love of ornament, which was very widespread among the Carthaginians, with a profusion of rings, bangles, pendants, earrings, necklaces composed of all sorts of materials, drops, head-bands, amulet-cases, etc.3

To the same love of display a number of artistic industries owed their importance—those of fine stones, particularly scarabs for use as seals, of articles of enamelled paste, of glass vases, of combs, mirror-handles, fan-handles, furniturefittings, and many small objects of ivory, and of painted or engraved ostrich-eggs.4

The ceramic industry was as prosperous as those of metal and the precious substances. The activity which it showed is attested not only by the innumerable pots dug up in the cemeteries but by the presence of workshops and kilns at Carthage and elsewhere, and by the marks, which are certainly Punic, stamped on vase-handles. Far the most of the articles produced by this industry were common utensils—jars, amphoras, ewers, urns, jugs, goblets, dishes, bowls, and lamps with one or two spouts, all made on the wheel and fired in the kiln, usually of a heavy, commonplace shape and painted with red, black, or brown networks, zigzags, or circles; some pieces are adorned with rather rudimentary palmettes, branches, or petals. From all this mass of uninteresting objects a few more exciting specimens emerge— pots shaped like animals and ewers with human heads; statuettes of women in a rigid attitude, figures making the gesture of prayer, and a few deities; medallions adorned with vegetable or animal motives; grotesque masks; and female busts.1

As a whole, the industrial output of Carthage is not distinguished by a single original feature in the methods of manufacture or in the shape or decoration of the articles. So far from showing any inventive spirit, it reveals a real inability to progress or to take on new life; it is affected first by the influence of Egypt and then by that of Greek Sicily. Active as they were, Punic metal-working and pottery did not contribute anything at all to the economic progress of the ancient world; they merely assisted the spread and development in North Africa of those two industries as practised for various lengths of time in the other parts of the Mediterranean.

We have very little information about the organization of industry at Carthage. We may take it that shipbuilding, at least in the case of warships, was a State industry. Carthage does not seem to have had huge industries or big workshops chiefly employing slave labour. It is probable that most trades—metal-working, goldsmith's work, jewellery, pottery—were practised either in medium-sized workshops, in which a few workmen served an employer, or by free craftsmen who might, in some cases, have one or two friends to help them.2

These manufactures chiefly supplied the home trade of the Carthaginian state; they also furnished articles of exchange to the shipowners and merchants who traded with the African tribes. Moreover, if some of these goods were exported abroad, Carthage imported similar articles of much better workmanship and finer style, which her ships brought from Greek lands.

We have seen that the first real progress made in North Africa by agriculture, stock-breeding, and industry was due to the Phœnician colonization and the influence of Carthage. But by far the most characteristic activity of Carthage was the trade, chiefly sea-borne, which for several centuries gave her a real hegemony all over the West.

We need not dwell on the small trade which went on in the towns between merchants and local consumers. This is a practice common to all civilizations, and, besides, we have no definite information about it in the case of Carthage and her African colonies. Much more important and characteristic was the trade which the great Punic city carried on with foreign countries, near and far.

Carthage imported, chiefly from the Greek countries and the East, a number of foodstuffs and many manufactured goods for the use of her people or her subjects. Sicily (especially Acragas), Campania, and the island of Rhodes, sent her wine, and much oil came from Acragas.1 From the Greek world, either Greece or Campania, she received, perhaps through Sicily, bronze articles, jewellery, and painted vases, among which Corinthian wares and pots made in Campania and Apulia have been found. Terra-cotta statuettes and bronze ewers from Cyprus have been discovered in the Punic cemeteries. Egypt also supplied Carthage with various articles of adornment.2 The African territory and colonial empire of Carthage supplied very little to her export trade— slaves and ores and metals, especially the lead and silver of southern Spain.

Carthaginian trade owed its prosperity and special character to shipping much more than to importation and exportation in the strict sense of the two words.

Either on her own account or through her colonies, Carthage received on her market or went long distances to obtain goods which she then distributed in the countries with which she had commercial dealings. The tradingstations founded by the Phœnicians on the coasts of the Syrtes—Leptis Magna, Œa, Sabrata, Gigthis, Tacape— which had become allies or vassals of Carthage, were connected by caravan with the great oases of the Fezzan and Ghadames, and by those oases with the Sudan and Central Africa, Although the Carthaginians have given no definite information about the trade that went on by these routes, one is justified in supposing that from those still mysterious regions they obtained black slaves, ivory, skins of wild beasts, ostrich-feathers, and gold. Another station to which they went for many products of Central Africa was on the Atlantic coast, beyond the Pillars of Hercules. From there they brought back skins, lions, panthers, antelopes, ivory, and gold, which they obtained in exchange for perfumes, pottery, and glass rubbish.1 On the European coast of the Atlantic, in Galicia and Asturias, in Brittany, and in Cornwall, the Carthaginian ships loaded up with tin and lead. We do not know the details of this transit trade; we have very little knowledge of what goods were given in exchange for these materials. We can only say that, in the Western Mediterranean and on the Atlantic coasts of Europe and North Africa, the Carthaginians, following the Phœnicians, played a part in sea-borne trade like that of the Dutch in the seventeenth century.

It is easier to determine what were the routes taken by this traffic, and what were its chief centres and geographical domain. In Africa itself, those of the old populations which remained independent do not seem to have given the Carthaginian traders much custom. The Numidian chiefs perhaps bought luxuries from them, arms, jewels, etc., but the needs of these tribes, which were partly nomadic and chiefly pastoral, were very limited. The Carthaginians did not consider it necessary to open roads far into the backcountry. Sales, purchases, and exchanges usually took place in the towns on the coast, which were almost all entrepôts and markets. The tracks over the Sahara which were taken by the caravans from Central Africa were not under the control of Carthage.

The true domain of Punic commerce was the sea. Merchants went to Phœnicia, Egypt, and Greece, but the chief activity of the shipowners was in the West. The documents which we possess and the archseological observations made in various regions bear witness to continuous trade relations between Carthage on the one side and Greek Sicily, parts of Italy, such as Campania, Latium and Etruria, and certain points on the coast of south Gaul and north-east Spain on the other. Here the Greeks and perhaps the Etruscans were serious rivals. Beyond the Pillars of Hercules, the Punic ships almost had the sea to themselves. The voyages of Himilco and Hanno, which were official expeditions organized by the State, leave no doubt as to the interest which the Carthaginian government took in those distant waters. Himilco was instructed to explore the European coast of the Atlantic north of Gades, and to take steps that the carriage of the ores and metals abounding on those coasts should be as far as possible kept in Carthaginian hands. Hanno, after passing through the Pillars of Hercules, sailed southwards along the African coast, and modern historians admit that he reached the head of the Gulf of Guinea and came near to the Equator. He founded several colonies on the coast of Morocco, the southernmost of which was planted on the island of Cerne, between Capes Juby and Bojador.1

Carthage also took energetic steps to keep the monopoly of trade in the Atlantic and all along the Mediterranean coast of Africa. In the Tyrrhenian Sea, in the Gulfs of Genoa and Lions, and along eastern Spain, she could not evict the Greeks, but she succeeded in keeping them out of all regions over which her political authority or commercial supremacy prevailed. At the beginning of the Punic Wars her commercial domain in the Mediterranean and Atlantic was very large.

To exploit that domain, Carthage had a material equipment, some elements of which are fairly well known to us. The merchant navy was renowned for the size of its vessels, large galleys driven by sail and, if necessary, by oars, and for the skill of its crews and commanders, who were not content to hug the shore but took to the high seas, observing the stars.2 This fleet found well-chosen and well-fitted points of call, shelters, and bases in numerous harbours. First, there was the merchant harbour of Carthage; its exact position and arrangement have given rise to many controversies, but it was certainly very large and very active.3 Then there were the harbours of the many colonies founded by the Phœnicians and Carthaginians, which stretched along the north coast of Africa and the south of Spain, wisely placed on a strait between the mainland and an island, or under the shelter of a headland, or at the mouth of a river. The most important of these seem to have been Leptis Magna (Lebda), Tacape or Tacapas (Gabes), Thapsus (Ras Dimas), Hadrumetum (Susa), Utica, Hippo Diarrhytos (Bizerta), Hippo Regius (Bona), Saldæ (Bougie), Iol, afterwards Iol Caesareia (Shershell), Gunugu (near Guraya), Tingi (Tangiers), and Lixus (near Larash) in Africa, and Gades (Cadiz) in Spain.

These ports and many other stations situated inside or outside the limits of the Carthaginian Empire served Punic commerce as entrepôts and trading-stations. Sometimes business took the form of the exchange of goods, or barter. Herodotos and the Periplus of Scylax say so definitely of the west coast of Africa.1 It was the same in the ports of the Syrtes where the caravan-routes of the Sahara ended and in the stations on the European coast where the Carthaginians obtained tin and lead.2 The use of money in commercial transactions seems to have been fairly late. Yet Carthage did not lack gold or silver; she obtained the former from Central Africa and easily procured the latter in Spain. It is possible that in their dealings with civilized peoples the Punic traders for a long time used ingots, which were weighed, or foreign coins, chiefly Greek.

It is agreed that Carthage struck no money of her own before the fourth century, or at the end of the fifth at the earliest. The first Punic coins were minted in Sicily, on the model of the Greek coins of that country. At Carthage itself and in Africa, minting did not start before the middle of the fourth century, and the coinage was inferior in quality to that of Sicily. There were Panic mints in Sardinia for bronze and in Spain for silver. It is curious that no Carthaginian coins should have been discovered outside the territories politically subject to Carthage; those found in eastern Algeria did not, perhaps, circulate there before the Roman period.3

In spite of defects in monetary organization, movable wealth, chiefly acquired by trade, was very considerable at Carthage. Business was held in high esteem. The aristocracy considered it no disgrace to devote its resources and energies to trade. Many nobles were shipowners or

MAP IV.—THE CARTHAGINIAN EMPIRE.

bankers. Carthage was one of the ancient cities in which capitalism was most powerful and weighed heaviest on the destiny of the nation. Hannibal seems to have seen this after the defeat of Zama, for he strove, by energetic measures, to deliver the State from the tyranny of the financial magnates. But it was too late. Fiscal organization had been in their hands too long. This very fact made the loss of Sicily, Sardinia, and Spain irreparable.

What proves, moreover, the supreme place which trade held in the private and public life of the Carthaginians is the general trend of the education of the young and the whole policy of the city.

The qualities which they endeavoured to develop in the young were, first and foremost, a love of undertakings in distant lands, smartness, if not roguery, in business, eagerness to make money and a passionate love of wealth, versatility combined with tenacity, a political intelligence capable of profiting even by apparently unfavourable circumstances, obsequiousness to the powerful, and merciless arrogance towards the weak. The Latin writers may perhaps have exaggerated the shortcomings of Punic honesty, fides Punica, but they did not invent them. The Carthaginians inspired dislike among the peoples of antiquity as a whole; the Greeks speak of them just as severely as the Romans.1

The general policy of Carthage seems to have been mainly inspired by commercial interests. "The Republic," M. Gsell writes," had a commercial policy, which may be summed up as follows: to open up markets for the Carthaginians by force or by treaties or by the foundation of colonies; to keep these markets to themselves in countries where it was possible to ward off all competition; where this was not possible, to govern transactions by agreements specifying reciprocal advantages; and to protect the freedom of navigation and the existence of cities and seaside trading-stations against pirates."2 Precious evidence of that policy survives in the two commercial treaties concluded between Carthage and Rome. The dates of these agreements may be disputed, but their existence and their purport are indisputable. The text has been preserved by Polybios. According to M. Gsell, the earlier of these treaties goes back to the end of the sixth

century, while the second was signed about the middle of the fourth.1 While the Carthaginians undertook to respect the coast of Latium and central Italy, not to attack any city there and not to build any stronghold there, they forbade the Romans to do any trade, or almost any trade, in the regions under their control, along the African coast from the Syrtes to the Atlantic, on the south coast of the Iberian peninsula, or in Sardinia. In the second treaty we find the following clauses:

"In Sardinia and in Libya, no Roman shall do trade, or found cities, (or land) longer than is needed to take on provisions and repair his ship. If he is driven there by a storm, he shall depart within five days. . . . Beyond the Fair Promontory2 and Mastia in Tarseion3 the Romans may neither seize plunder nor do trade and may not found cities."4

It is likely that similar agreements were made by the Carthaginians with the Greeks, and perhaps also with the Etruscans. "From the sixth century onwards," M. Gsell concludes, "the Carthaginians established commercial monopolies in the West. In the fourth century, they allowed no competition in Africa west of Cyrenaiea, in Sardinia, in the south of Spain, or beyond the Strait of Gibraltar."5 Only the port of Carthage was open to foreign trade, with serious safeguards, but under a real control; the same conditions were granted to the Romans in the ports owned by Carthage in the west of Sicilv.

Piracy was practised by all sea-faring peoples. The danger was especially serious for Carthage, whose wealth and power were founded on marine trade. The Punic State put it down severely. Various clauses in the treaties concluded between Rome and Carthage suggest that the two cities mutually undertook to abstain from such aggression.6 Similar undertakings were made between the Carthaginians and Etruscans.

Although there are many gaps in our knowledge of Punic commerce, it is at least certain that trade, chiefly sea-borne, was by far the most important element in the economic activity of the Carthaginians. To business Carthage owed her prosperity; through business she played a big part in the history of the Western Mediterranean; business gave her her special character among the great cities of antiquity. It would be absurd to deny the influence which, by her commercial relations, she was able to exert on the destinies of North Africa. But her history shows the superficiality and weakness of a civilization in which the chief drivingpower of human activity is the conquest of riches, and there is no endeavour to achieve, by the side of and by means of economic power, political, intellectual, and moral progress.

1 For this chapter I have chiefly made use of S. Gsell's masterly Histoire ancienne de l'Afrique du Nord, vol. iv, bk. i (LXXI); cf. LXXIV.

2 LXXI, vol. i, p. 234.

1 Ibid., p. 401.

2 Ibid., p. 465.

1 Quoted in LXXI, vol. iv, p. 40.

1 Ibid., p. 41.

2 Ibid., p. 8.

3 Ibid., p. 2.

1 It is not certain that the quarries of Numidian marble (afterwards famous) near Simitthu (Shemtu) were opened by Carthage.

2 LXXI, vol. iv, p. 49.

1 LXXI, vol. iv, pp. 74 ff.

2 Ibid., pp. 83 ff.

3 Ibid., pp. 85 ff.

4 Ibid., pp. 93 ff.

1 Ibid., pp. 57 ff.

1 Ibid., pp. 53 ff.

1 LXXI, vol. iv, pp. 27, 29.

2 Ibid., pp. 154 ff.

1 Ibid,, pp. 141 ff.

1 On the expeditions of Himilco and Ilanno, see LXXI, vol. i, pp. 468 ff.

2 LXXI, vol. iv, p. 111.

3 On the port of Carthage, see LXXI, vol. ii, pp. 38 ff.

1 LXXI, vol. iv, pp. 141 ff.

2 Ibid., p. 130.

3 LXXI, vol. ii, pp. 324 ff.; vol. iv, pp. 130, 135.

1 LXXI, vol. iv, pp. 217 ff.

2 Ibid., p. 113.

1 LXXI, vol. i, p. 461.

2 Cape Sidi Ali el-Mekki, N. of Carthage.

3 In Spain, near C. de Palos and the site of the present Cartagena.

4 LXXI, vol. iv, pp. 118 ff.

5 Ibid., p, 122.

6 Ibid., pp. 125 ff.