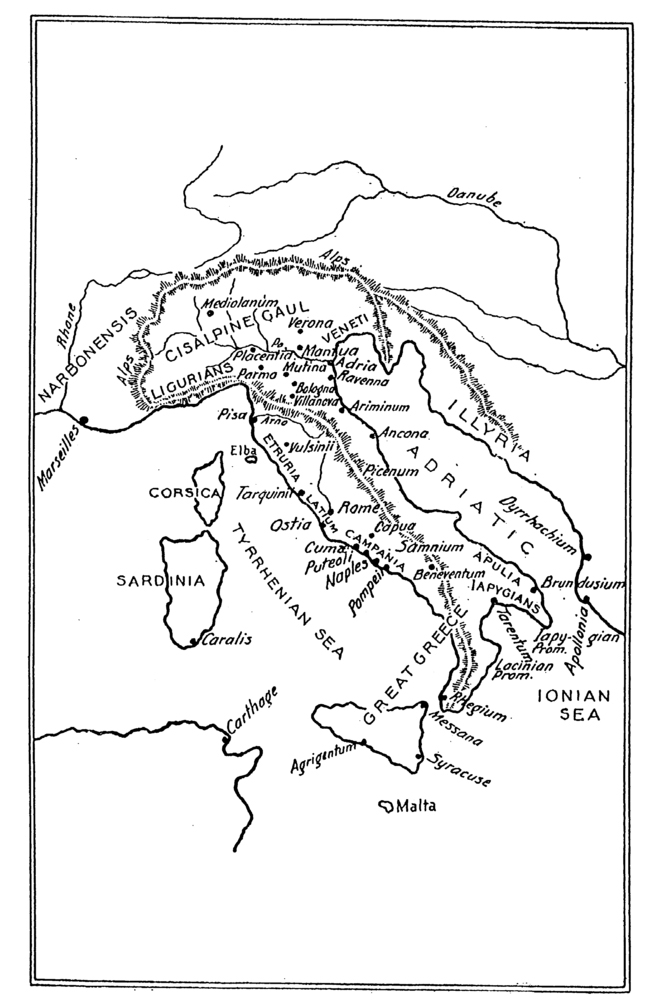

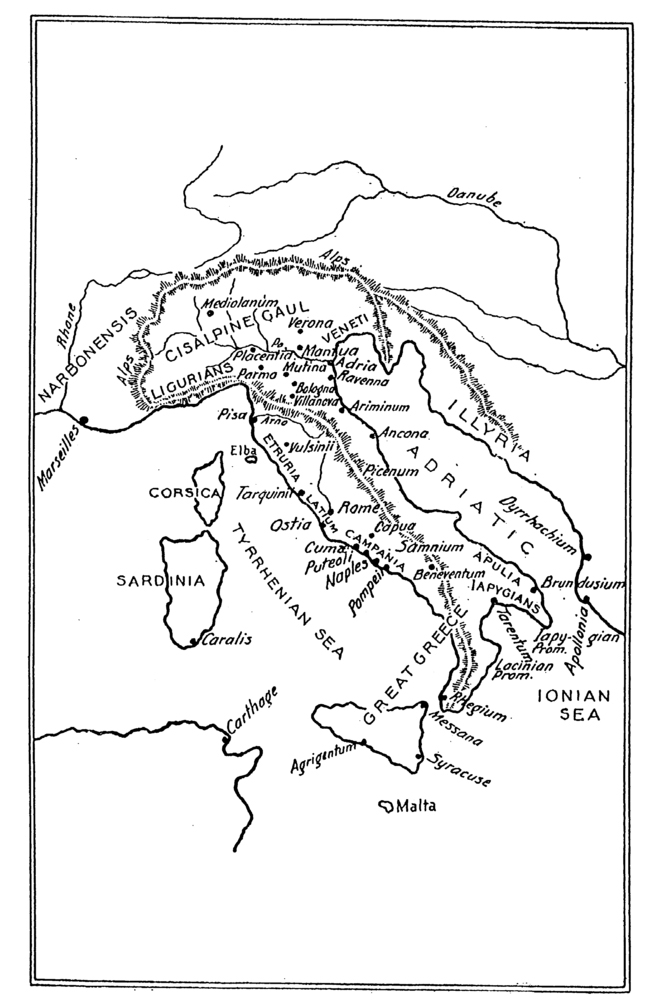

MAP V.—ITALY UNDER THE ROMAN REPUBLIC.

THE economic evolution of Italy, in the earliest period of its history, is more complex than that of Western Europe and North Africa. No doubt, one finds the characteristic ages of prehistory in their accustomed order, Palælithic, Neolithic, Copper, Bronze, Iron. But in the course of these great stages in progress, towards the rational use of natural resources, towards the methodical and fruitful organization of human labour, Italy underwent many migrations of various origins and was subjected to influences as varied as they were numerous. By its general shape, stretched out from north to south from the Alps to the Strait of Messina, by its position between the two great basins of the Mediterranean, by its three fronts on the Adriatic, the Ionian Sea, and the Tyrrhenian Sea, and by its very relief and its topography, which favours division rather than unity, Italy belongs both to Central Europe and to the Mediterranean world. It faces both east and west; the peoples which occupied it and the civilizations brought to it. from outside or developed on its own soil did not merge into a truly national unity until very late. There are, moreover, obscurities and gaps in the prehistory of Italy. To dispel the former and bridge over the latter hypotheses have been suggested and systems erected which do not always appear very solidly founded.

Here, at least, are the mam features of the process. After the Palæolithic period, many traces of which have been found from the Po valley to Sicily, the Neolithic Age seems to have been of great importance in Italy. It was the inhabitants of that period whom ancient tradition designated by the names of Ligurians and Sicels and regarded as the most ancient people of Italy. These populations were of different races, and the word " Ligurian " must be used to designate a state of civilization rather than a racial element.

At the end of the Neolithic Age, the metals appear, first copper and then bronze. North of the Apennines, numerous palafittes or lake villages are built in Lombardy and Venetia, and terramare, villages on piles built on dry land and surrounded by a moat full of running water, appear, especially in Emilia, from Piacenza to the neighbourhood of Bologna. Most prehistorians hold that the inhabitants of the lake villages and terramare came to Italy from Central Europe and formed the advance-guard of the Italici properly so called. The theories according to which they were Ligurians, or Etruscans, or even Celts, are now abandoned, or very much contested. The Bronze Age with its lake villages and terramare was followed by the Iron Age, represented in Italy by the Villanovan civilization. This was brought in by the second line of the great Italic migration, the Umbrians and Sabellians, by whom the immigrants who had previously come down from the Alps to the banks of the Po and its tributaries were driven onwards into Central Italy. The Celts did not appear in that region till much later.

While numerous populations were entering Italy from the north, other bands were coming in from the east, from the Balkan Peninsula, starting from Illyria. Some of these bands went round the head of the Adriatic by land, others crossed that sea at the middle and landed on the coast of Picenum, and others seem to have come by the Strait of Otranto. The Veneti in the north, the Picentines and Peligni in the centre, and the Iapygians in the south are generally regarded as being of Illyrian origin.

These various migrations, from Central Europe by the passes of the Alps and from Illyria by land and sea, had come to an end about the beginning of the first millennium before Christ. Already the civilization of Italy had been affected by Eastern and Mediterranean influences. In the Neolithic Age we find the influence of pre-Minoan Crete in Sicily, and it grows stronger during the Copper Age. In Villanovan times, north-eastern Italy received from still further, from Cyprus and Phœnicia as well as from Greece, if not models, at least inspirations which affected local industries.

All this was only the very modest prelude to a much more extensive and much profounder action. Two peoples, two civilizations from the Eastern Mediterranean, arrived in Italy between the end of the eleventh century and the eighth —the Etruscans and the Greeks. In the days of its greatest expansion, the Etruscan power, whose centre always remained in Tuscany, extended from Campania to the valley of the Po. The field of action of the Greeks, even if Ave admit that they founded colonies, which afterwards disappeared, in central and northern Italy, on the Etruscan coast, and at the head of the Adriatic, was chiefly southern Italy and Sicily. But Great Greece and Sicily were for hundreds of years an integral part of the Hellenic world, and their economic history belongs in the main to that of Greece.1 Their share in the economic life of Italy was chiefly marked by the trade relations which they maintained with Etruria and Latium and the influence which they had on the civilization of those two regions. The economic history of the Etruscans, on the other hand, belongs to the history of Italy, and it is not too much to say that before Rome arose Etruria gave the economic life of Italy its first effective and native impetus.

The primitive period of Italian economic life therefore ends with the arrival of the Etruscans in the peninsula. What were the general characteristics of that life before this capital event took place?

Primitive Italy passed through a succession of economic phases very similar to those which we have seen in Western Europe. Palæolithic man lived by hunting, fishing, and gathering wild fruit. His industries were confined to chipping stone and preparing bone, horn, and perhaps wood, skins, and leather. The first real progress was made in the long Neolithic Age. It is hard to say whether agriculture was practised in Italy from the very beginning of this period,1 but at least one of man's greatest conquests over hostile nature then took place—stock-breeding appears. In any case, when the Neolithic Age ended, in the Copper Age, the chief forms of economic activity already existed. Man had domesticated several races of animals and had learned to till the soil; he practised several industries previously unknown, including pottery and metal-working; and he had come into relations with Crete and the Ægean civilization, from which he doubtless received manufactured goods.2

This progress became more marked in the time of the lake villages and terramare. Here we can come down to details, thanks to the abundant evidence found on the sites of these primitive dwelling-places. " The inhabitants of the Terramare, a numerous and flourishing people judging by the remains they have left, mark a stage of culture much higher than that of the Neolithic Age. While hunters and fishers like their predecessors in Italy, they were primarily an agricultural people. . . . They cultivated edible and useful plants (wheat, beans, vines, fruit-trees, and flax) and pastured their flocks and herds (cattle, swine, sheep, barnyard animals). They carried on a textile industry (weaving for clothes and the plaiting of twine), wood-working (axe-hafts, baskets of withies, spades, knives, chisels, polishers, dishes, basins, ladles, straight or curved staves, and bows), bone-working and horn-working (needles, knives, hammers, chisels, combs, hair-pins, and spindle-whorls), and a ceramic industry (pottery, unbaked or baked at the open fire, and distinguished especially by a crescent-shaped projection on the handle and its decoration, lines, furrows, or ' kicks '). Finally, a bronze industry characterized this new civilization. Bronze was used for arms (axes, daggers, knives, arrow-heads, and swords) and implements (razors, sickles, blades, tweezers, hair-pins, and combs), and, finally, for ornaments (little wheels, pendants, and violin-bow fibulæ). The metal was cast in a mould, but technique was still primitive." 3 The same civilization developed in the Italian palafittes of the Venetian lakes, in Tuscany, in Campania, and in Sicily.1

In Italy as elsewhere in Europe, the Bronze Age was followed by the Iron Age. The best known, most abundant, and most fully studied evidence of that new form of civilization is the deposit of Villanova, in the Bologna district.2 Economically, Villanova is chiefly distinguished from the terramare by the progressive introduction of iron into daily life; little by little the new metal took the place of bronze for the manufacture of weapons, tools, and articles of luxury and adornment.3 It is possible that the working of the iron-ores of the Tuscan coast and the island of Elba dates from this period.

The civilization brought into parts of Italy—Venetia, Picenum, Apulia—by the Ulyrian invaders is not earlier than the Iron Age. It differs in some respects from that of Villanova, but the economic practices of the two are similar. M. Piganiol notes two interesting details in respect of Picenum —the abundance of iron and scarcity of bronze, and the huge abundance of amber.4

So, before the Etruscans and Greeks came to Italy, the economic development of the country had been mainly determined by influences coming either from Central Europe across the Alps or from the Balkan Peninsula. No migration had so far brought truly Mediterranean or Eastern racial elements into the peninsula. It seems, however, that even in those early times there were commercial relations between Italy and the pre-Hellenic East. In the Neolithic Age, Sicily already knew the products of pre-Minoan Crete.5 During the Copper Age, the influence of the Ægean civilization became more marked. At the same time the people of the lake villages and terramare, being bronze-users, must have been in relations with the countries which produced tin or with the stations dotted along the road by which that metal came to the Mediterranean. Later, part at least of the iron used by the Villanovans and their contemporaries came without any doubt from the mines of Central Europe. The presence of many amber objects in the Picentine cemetery of Novilara bears witness to the importance assumed in Italy by the trade in this commodity.

Whatever may have been the subsequent importance of the Etruscan immigration and the Greek colonization on the destinies of Italy, the country in which these two peoples landed was no longer, at the beginning of the first millennium before Christ, a primitive country economically. Agriculture, stock-breeding, industry, and trade had long been in existence there; human activity was exercised in a variety of fruitful occupations. The ground was well prepared to receive the seeds brought by the new-comers from the East and Greece.

In spite of the discoveries of archæology and the studies of many scholars, the history and civilization of the Etruscans are still in many respects obscure and enigmatic. Some important facts are, however, regarded as beyond dispute. It is almost universally agreed today that the Etruscans came to Italy by sea, that they came from the Eastern Mediterranean, and more exactly from the coast of Asia and some islands in the northern Ægean, and that they landed on the west coast of the peninsula between the mouths of the Tiber and the Arno. The migration took place about the tenth century B.C. First they occupied the country lying between the coast of the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Apennines, Etruria properly so called, now Tuscany; then they extended their power southward to the northern borders of Campania, and north-eastward beyond the Apennines all over the middle and lower valley of the Po. Between the seventh and fifth centuries, the Etruscan Empire stretched over northern and central Italy from the foot of the Alps to the Silarus. Melpum (the future Mediolanum), Placentia, Mantua, Verona, Ravenna, and Felsina (afterwards Bononia) in the north, the twelve chief cities gathered round Vulsinii and afterwards Rome in the centre, and Cumæ, Capua, Naples, and Pompeii in the south all came under the sway and almost all under the influence of Etruria. Not until the fifth century did its power decline, when the reaction of Latium and Rome, supported by the Greeks of Cumæ, gradually robbed it of all the land which it had occupied south of the Tiber, and the Gallic invasion of northern and north-eastern Italy drove it back across the Apennines. In the fourth century, " Etruria was in full decay, and ceased to count seriously in Italy."1

But its influence on the general civilization and the economic life of ancient Italy was intense and profound. The regions over which it ruled were truly transformed by it, and the progress which it set going was not undone nor even injured.

The Etruscan civilization was essentially of an urban character. The terramare and the mere agglomerations of dwellings of the Villanovan period were now succeeded by true cities, surrounded by strong walls, built on a strict geometrical plan, and often crowned by an acropolis. In these cities buildings of stone, baked brick, or pisé (beaten earth) made their appearance, whereas the dwellings of the previous periods had been made of branches, straw, and mud. Like the abodes of the living, the tombs of the dead were properly built chambers, varying in size, with walls of massive stone blocks and solid pillars to support the roof.

The Etruscans were not only architects; they were also, and perhaps mainly, remarkable engineers. Ancient tradition regarded them as the authors or inspirers of the drainage-works which for hundreds of years made the Tuscan Maremma, the Roman Campagna, and the Pontine Marshes relatively healthy spots. It was to the time called the age of the Tarquins, that is, the period during which Rome was ruled by the Etruscans, that men ascribed the building of the sewer, or rather drainage-channel, known as the Cloaca Maxima, by which the swampy valleys round the Palatine were drained. Outside the towns, the Etruscans cleared forests, reclaimed much land from the stagnant water which covered it, dug quantities of little channels or cuniculi which carried off water which lay on or immediately under the surface of the ground, and, by a hydraulic feat which may serve as a model at this day, brought into use or taught the native populations to bring into use, without any serious risk to their health, a soil which by nature was hostile and unhealthy.1 Elsewhere, for example along the Po and its chief tributaries, they built embankments and cut ditches to hold, direct, or slow down the flow of water coming from the Alps or the Apennines.2

Agriculture then developed marvellously in the countries subject to Etruscan influence. We have no details enabling us to describe the various methods and the results of that activity, but can at least judge of its importance when we note that Rome afterwards exacted heavy contributions in corn from the Latin and Etruscan cities which she conquered.

Industry also made some progress, but the Etruscans seem to have introduced fewer novelties in this domain. They opened up many large quarries from which they obtained the materials needed for building their city walls, public buildings, and dwelling-houses. They doubtless gave a great impetus to the extraction of ore on the Tuscan seaboard and in Elba. The presence of those ores is still attested by the modern names of Monte Argentaro, Piombino, and Porto Ferraio, and they may have been known as early as Villanovan times. From the forests of Corsica, after the departure of the Phocæans, and those which covered the Apennines they obtained plenty of timber. The various building industries, principally masonry and heavy carpentry, throve in Etruria. Pottery developed especially. It is true that most of the vases found in the cemeteries are of Greek origin, and do not therefore represent the national industry of the Etruscans; the use of terra-cotta in the decoration of buildings, the modelling of full-sized statues of terra-cotta, and the manufacture of polished black vases (bucchero) all seem to have been Etruscan inventions. They certainly did not introduce pottery into Italian industry, but, thanks to their encouragement, terra-cotta won a far greater place in it than before.

It was the same with metal-working. Among the many bronze objects of which the funerary furniture laid in the tombs was composed, some no doubt were bought by the Etruscans in Greece; but they also made them, with less art and delicacy, of course, but with undeniable technical skill. All this bronze-ware, cast, repoussé, or adorned with incised patterns, points to the progress made by metallurgy in Etruria.1

Bone and ivory were also worked.

Things made by the Etruscans themselves have not only been found in Etruria properly so called; they have been discovered in Rome and Latium on one side and in the Po valley on the other. This diffusion enables one to estimate the importance of the influence exerted by the Etruscans on the industry of ancient Italy.

The influence of their commercial activity was considerable, By the mere extension of their empire, by the extent of territory subjected to their sway, the Etruscans were led to maintain an active trade with the Greek colonies of southern Italy and with the peoples of the Alpine regions, both in the southern valleys and on the northern slopes of that range. But most of their trade was done by sea. Although conditions on the Tuscan coast were not favourable to navigation, and although even those of their cities which were nearest to the sea, Caere, Tarquinii, Vulci, Vetulonia, were not actually on the coast, they obtained a naval power in the Western Mediterranean which enabled them to hold their own against the Greeks and to treat Carthage as an equal. On the Adriatic north and south of the delta of the Po, Hadria, Spina, and Ravenna were busy ports.

The discoveries made in the Etruscan cemeteries, both north and south of the Apennines, have proved that the commercial dealings of Etruria were chiefly with the Greek world. The importation of painted vases and bronze articles seems to have been the most important part of this trade. The potters and bronze-workers of Corinth and Athens were the chief suppliers of Etruria. It is not known whether Etruscan ships went to get these precious wares in the producing countries; perhaps the Greeks of Sicily brought them. Nor have we exact details about the nature and amount of the trade which Etruria did with Carthage. We do not know how its commerce was organized. We do not know what goods the Etruscans transported to their neighbours, nor to what extent they used money. Etruscan epigraphy and numismatics are still very obscure.

Much as we may regret the gaps in our knowledge of the economic life of the Etruscans, we know enough of it to be able to appreciate the great part which it played in the economic history of Italy before the country was united under Roman rule.

Whatever the relations of the centre of the peninsula and the Po valley may have been with the Ægean and Eastern world in prehistoric times, it was chiefly thanks to the Etruscans that those regions became acquainted with Greek civilization and first felt its beneficent influence. Not only did they bring into the country agricultural and industrial methods previously unknown, which represented an enormous advance upon the habits and processes of earlier ages, but, by constantly keeping in contact with Hellenism in the most brilliant centuries of its history, they caused Greek influences to spread more and more among the peoples of Italy—influences which were as potent in economic matters as in intellectual and moral matters. It was under the guidance of Etruria that Rome herself took her first steps on that road. When the Etruscan power declined, when the Etruscan Empire collapsed, and Rome gradually became the most powerful city in Italy, she owed her triumph in great part to the fact that she had received the seeds of her economic future from Etruria.

The city which was to preside for several hundreds of years over the economic synthesis and expansion of the ancient world did not begin to rise to that magnificent destiny until very late. The oldest inhabitants of Latium, in particular those who occupied the swamp-girt hills on which Rome would one day rise, moved more slowly along the road of economic progress than the peoples established in the valley of the Po, to say nothing of the Etruscans. The so-called Latian civilization, which was contemporaneous and related with that of the terramare, was very little affected by Villanovan influence. Down to the time when, thanks to the neighbourhood of Great Greece and the Etruscan domination, Latium began to feel the beneficent effects of contact with two higher forms of civilization and economic activity, the earliest Latins, or Prisco-Latins, were on the whole " still only poor, half-nomad shepherds, living a rude life and still observing often ferocious customs, if we may judge from the typical survival of the rex nemorensis, ' the king of Nemi.' They were acquainted neither with Writing nor, probably, with the agriculture in which they were to be instructed by the Etruscans. That is the . . . environment in which Rome was born and grew up for centuries."1

The history of the beginnings of Rome has gradually been brought to light by modern criticism and the archæological discoveries made within the last twenty-five years on the site of the city. There still remain many uncertain details and belts of darkness. It is, however, possible to perceive the chief stages of her development and to obtain exact economic data from the facts known. At the beginning of the history of Rome, the Aventine was the seat of a human group, composed chiefly of hunters and herdsmen, settled in a very humble way among the woods and in the few clearings of the hill. Somewhat later the village of Cermalus or Germal was built, on the west end of the Palatine. Then the neighbouring hill-tops and brows were occupied, in what order, one cannot say. The eastern part of the Palatine was covered by another village, Palatual; four were established on the Esquiline and Cælian; the Velia, a ridge connecting the Esquiline with the Palatine, was inhabited. These modest communities drew together; so the Septimontium was formed, the League of the Seven Hills, the organization of which appears as an intermediate stage between the primitive, isolated village of Cermalus and the city of Etruscan and Servian times, which is often called the City of the Four Tribes. The Aventine on the one side and the Capitol, Quirinal, and Viminal on the other remained outside the League of the Seven Hills; they were not, however, uninhabited, for they bore villages like the other hills of the future Rome.

Before all these villages were concentrated and combined in a single organism, a true city, which was to all appearance the material and administrative achievement of the Etruscans, their economic methods were still rudimentary. Stockbreeding, the principal occupation of the inhabitants, supplied them with their chief resources. Words like pecunia, obviously derived from pecus, and the name of Mugonia given to the gate of the Palatine opening on to the Velia bear witness to the importance of cattle in the daily life of that distant time. The ground seems to have been tilled only enough to meet the needs of the family.1 The dwellings were mere huts, rectangular, circular, or elliptical, with walls of branches or reeds coated with badly baked clay. The industry revealed by the earliest cemeteries excavated on the site at first consisted in the manufacture of a clumsy pottery and weapons, tools, and utensils of bronze, more rarely of iron. However, one sees some progress. The use of the wheel enabled the potters to turn out vases which were less crude and to invent and execute shapes which were less barbaric, and the use of iron spread more and more. At length the economic isolation of Latium came to an end. The first relations with the Hellenic world are betrayed by the importation of vases adorned with geometrical patterns or animals, small objects such as beads, whorls, and statuettes of glass paste, and disks of amber. It was becoming clear that there were advantages in the geographical position of the spot round which were gathered the villages on the monies and colles which would one day be surrounded by the walls of Rome. There two routes of the greatest economic importance intersected—the River Tiber, which led up from the Tyrrhenian Sea into Latium and a large part of central Italy, and the land-road which connected the north of the peninsula with the south, running through Etruria, Latium, and Campania.2 It is not impossible that even at this time there was a village at the mouth of the Tiber, where the port of Ostia afterwards arose, but it is unlikely that it was in any way dependent on those which stood some miles up the river.3

A new period in the general and economic history of Latium and Rome began with the Etruscan expansion. Careful as Roman tradition was to conceal, distort, or soften down anything in the past which might detract from the pride and glory of Rome, it admitted that the Etruscans had ruled for a fairly long time over Latium and, in particular, over the collection of villages by the Tiber which occupied the site of the future capital of Italy. It credited the Etruscan Kings with two works of capital importance in the history of the city—the Cloaca Maxima and the stone fortifications known as the Wall of Servius. Here again, modern archæology and criticism have greatly added to the information provided by the Roman annals.

It was the Etruscans who really created the city of Rome, both in hard bricks and mortar and in political and administrative organization. By draining off the water of the swampy ground between the various hills into the Tiber, and by enclosing in a single wall all the inhabited hills from the Quirinal and Viminal in the north to the Aventine in the south and from the Esquiline and Cælian in the east to the Capitol in the west, they founded a solidly constituted urban organism at a point which was admirably chosen not only from a military and political point of view but also from an economic one.

The mastery of the Etruscans in the matter of public works and engineering, which was always acknowledged, was doubtless also applied, although no ancient evidence expressly mentions the fact, to the reclamation and working of the land of the Roman Campagna and the neighbourhood. Then the new city, in addition to the old resources, which consisted chiefly in stock-breeding and forestry, had agricultural produce—corn and fruit, especially olives and vines. Agriculture came to enjoy a real prosperity, in a large district which was afterwards the domain of malaria.

The birth of a new city and the rise of agriculture in all the surrounding territory attracted foreigners to Rome, craftsmen and traders for the most part. This was, at least to some extent, the origin of a social organization which had serious consequences on the economic development of the Roman State. Moreover, under the encouragement of the political masters of the country, industry made great progress. The huts of wood and reeds were replaced by stone houses; public buildings arose, for example the oldest temple on the Capitoline; the decoration of these buildings, fragments of which have been found, bears witness to the advance of the ceramic industry in Rome itself. Iron-working doubtless developed in the same period, for the manufacture of arms of offence and defence was necessary in a place of such strategic importance. In short, as soon as real town life appeared it gave birth to and fostered every form of labour which is closely connected with it.

Commercial activity developed simultaneously. In this respect, Rome, now one of the chief towns of the Etruscan Empire, benefited by its geographical position between Etruria and Campania. It stood on the great land-road connecting the two countries, and was perhaps the most important station on it. Ships going up the Tiber moored at the foot of the Aventine, on the left bank, where the ground was suitable to all the operations which make up the activity of a port.

Rome was now in being. Poor villages scattered over hills, which were separated by unhealthy and barren low ground, had given place to a healthy city, protected by a strong wall, surrounded by a territory which was methodically farmed, and inhabited not only by tillers of the land and stockbreeders but by workers and traders—ready, in short, to profit by all the favourable economic conditions which its position in the heart of central Italy gave it.

The decay of the Etruscan power, which had been the pioneer of this early progress, did not damage the future of Rome. But that future was to lie on very peculiar ways, determined by the external history of the city.

The history of Rome in the first centuries after the decline of Etruria is certainly overladen with legends in the Roman annalists, and we cannot accept all the details taken from them by Livy, Dionysios of Halicarnassos, and their successors. Modern criticism, even the mildest and most cautious, discovers in the official tradition repetitions, duplicate versions of one story, and episodes of subsequent invention, in brief, a whole body of reconstruction and interpretation, the accuracy and foundation of which are very disputable. In spite of these obstacles, it is possible to trace the rise of the Roman city through its most important stages. In her advance to leadership there were halts, and even retreats. Rome was not always victorious. She underwent the Gallic invasion after the battle of Allia; her glory was dimmed by the disaster of the Caudine Forks; she had to pull herself together at the menace of Pyrrhos,' the ally of Tarentum (Taras). But none of these set-backs was decisive, none of these dangers was fatal. Through changes of fortune which sometimes brought her near to extinction, Home extended her sway over Latium; over the bordering districts, the countries of the Volsci, Hernici, Æqui, and Sabines, and southern Etruria; then over all central Italy from one sea to the other, the rest of Etruria, Umbria, Picenum, Campania, and Samnium; lastly, over the south from Cumæ (Cyme) and Naples to Rhegium and Tarentum. These progressive conquests, which brought more and more territory under the power of Rome and made her the mistress of the whole peninsula by the middle of the third century B.C., were bought at the cost of continual, almost annual fighting. In addition, the possession of a coast-line as extensive as that which runs round Italy from the mouth of the Arno on the Tyrrhenian Sea by the Strait of Messina and the lapygian Promontory to Umbria gave Rome a power on the sea which supplanted that of the Etruscans and Greeks and would presently come into conflict with that of Carthage. The wars which she had to maintain in order to extend her political domain in this way and the actual results of her victories had great and far-reaching effects on her economic life.

First of all, the military organization of the city contributed to that development. The Roman army was not at that time, as it became later, a professional army; it was a militia, whose service was on principle temporary. The citizens were called up at the beginning of each campaign, and at the end they returned to their homes, without receiving any pay. They were liable to these military duties from the age of seventeen to that of forty-five. The strength of the legions lay chiefly in the class of small and middling landowners and free tenant farmers. Every man had to provide his own equipment. Let us try to see the economic consequences of this state of things. In the first days of spring, news is brought that the Volsci, the Æqui, the Sabines, or the Etruscans have attacked Roman territory. The Consuls raise one or more legions, according to the strength of the aggressors. The citizens thus recruited must at any moment leave their fields and their beasts. Since they get no pay, the cost of the campaign falls on every man. They may be killed, wounded, or taken prisoner, and if they come home it may be as victors or as vanquished. Even if they return safe and victorious, they often find their farms neglected, since no one has been able to do the work in their absence; their fields may even have been ravaged and their cattle driven off by the enemy.

This calamity prevented them, as we shall see later, from sharing in the profits of victory, when the war ended favourably at Rome. So they were without resources. But they must live till the next harvest. So they borrowed, and fell into debt. In Rome the laws on debt were very hard. Although we know no case of a debtor who, being unable to pay at the term, was put to death or sold as a slave by his creditor, it is at least certain that he fell, by the procedure of the nexum, into an absolute bondage, and that, being unable to pay his debt in kind or coin, he had to do so by working for his creditor on the hardest and most humiliating terms. " The nexi, delivered helpless to the greed and cruelty of their creditors, saw no term to their misery."1 The details which the ancient historians give us about the problem of debt in Rome and the various solutions which were attempted are difficult to accept without criticism. But this was, without any doubt, one of the causes which contributed to ruining the middle class and swelling the mass of the poor, the landless, the proletariate.

Another cause of the same economic and social evolution was the manner in which victorious Rome treated all or part of the conquered peoples. We know that a fairly large number of towns in Latium, the names of which were known and have been preserved by Roman tradition, disappeared at an early date. Some of the inhabitants of these towns were transferred to Rome. Those belonging to the local nobility may perhaps have been incorporated in the Roman Patriciate, while the others were absorbed by the Plebs, and this influx still further upset the balance between the two rival elements of the Roman people.

Nor was this all. Economically, perhaps the most serious result of the conquests of Rome in Italy was the change which took place in the ownership of land, in its character, its organization, and its distribution. By the ancient laws of war, a conquered city ceased to belong to itself and became in every respect the property of its conquerors. Its territory legally became their absolute property. In practice, Rome did not confiscate all the land conquered; indeed, she left the greater part of it to the former owners, under certain legal and fiscal conditions. The rest she divided into several parts. Part she sold or distributed to individuals who enjoyed the full ownership of it; this became agri privati, over which the Roman State no longer had any right. Another part she leased out, usually by auction, for an annual rent; this land continued to be the legal property of the State, the farmers only having the possessio of it. Another part was conceded to the first occupier, who had to pay the State an annual rent like the farmers of the previous category. The lands of these two last classes did not become agri privati, but remained part of the ager publicus. Now, it came about, by the mere force of circumstances, that sold land, leased land, and land conceded to the first occupier were all alike taken up by wealthy Patricians or Plebeians who had made money. The small and middling landowners and free tenants, being ruined by the war as we have seen above, could neither buy the first kind of land nor hire the second, and the land which was conceded to the first occupier almost all fell into the hands of the rich, who alone had the equipment needed to make it productive.

This was the origin of the land question, which was as serious and acute as that of debt. Whatever one may consider to be the date of the Licinio-Sextian Laws, placed by Roman tradition in 307 B.C., whatever one may think of their authenticity as measures taken about the middle of the fourth century B.C., the fact that such laws were passed proves, first that the mass of the poor suffered cruelly from the greed of the rich and the practice of usury, and secondly that the Patricians and wealthy Plebeians had appropriated enormous areas, each over 500 jugera, of the public land. In consequence, while for various reasons small and medium properties became fewer, big properties increased and invaded the ager Romamis. The distribution of individual allotments of land in the Roman or Latin colonies was an insufficient palliative to a situation which was full of danger for the future, especially since the laws passed in an attempt to solve the two problems of land and debt were usually either openly violated or quietly evaded.1

About the industry of Rome at this time, we have less information than about the development of landed property and its consequences to agriculture. It is likely that the advance of the power of Rome and the growth of the city helped to attract craftsmen and to develop industrial work. The metal-workers, weavers, potters, goldsmiths, armourers, and manufacturers of toilet articles seem to have constituted the busiest trades, and doubtless already made up a large part of the Plebs.2 The institution of the worship of Minerva, the great goddess of workers, on the Aventine is evidence of this economic movement and definitely shows its character.3 The Vicus Tuscus of Rome, as the Yelabrum was called, is believed to have been originally inhabited by craftsmen from Etruria. Industry remained stationary, however, and played no very great part in the economic life of Rome from the fifth century to the third.4

Trade, on the contrary, made marked progress. Thanks to her geographical position, Rome became the chief market of all central Italy, and she was near enough to the sea to be in touch with the marine trade which then flourished in the Western Mediterranean. Grain was imported in great quantities at an early date. There is evidence for this in the introduction into the Roman religion of the Greek triad of Demeter, Dionysos, and Core, under the old Italic names of Ceres, Liber, and Libera, which Roman tradition placed in the first years of the fifth century. " It went together with the development of a very active trade in corn between Rome and the regions of the south of Italy, Campania, and Sicily. . . . Native production was not sufficient to meet all needs, and the extra flour required to feed the citizens had to be procured outside Latium. Consequently, a movement of foodstuffs, chiefly corn, set up from the neighbouring districts to the mouth of the Tiber."5 No less significant is the appearance in Rome of Mercury, the god of traders who hailed, like the triad of Ceres, Liber, and Libera, from the Hellenized parts of southern Italy.1 The trade of Rome and Latium with Great Greece seems to have been fed to some small extent by the products of the ceramic and metal-casing industries. It is possible that Rome exported to the Greek world copper which she bought in Etruria and wool and hides which she obtained from the pastoral peoples of the Apennines.

Although we know little of the details of Roman trade in this period, we can at least obtain an idea of its expansion, thanks to certain facts and several documents of the greatest interest. Even if we admit that the Roman colony of Ostia was not founded before the middle of the fourth century, we may at least be allowed to suppose that an inhabited centre previously existed at that spot, and therefore that marine trade already made use of the mouth of the Tiber. The text of the first commercial treaty concluded between Rome and Carthage mentions,among the towns subject to Rome, Antium, Circeii, and Tarracina, and Polybios, who has preserved the text for us, declares that the treaty was signed " under the first Consuls of the Republic," that is, in 509-508 B.C. Modern historians do not agree as to how much trust should here be placed in Polybios. Messrs. Gsell and Frank accept his date;2 M. Homo holds that he has made a mistake, and that this first treaty is not earlier than the middle of the fourth century.3 Even if we adopt this latter view, it remains certain that as early as 350 Rome had control of the ports situated along the coast of Latium and the Volscian country. This contact with the sea and this control of several ports made it necessary for Rome to possess a merchant navy, and indeed this fact emerges from the very wording of the two treaties which she struck with Carthage:

" Neither the Romans nor their allies shall sail beyond " (i.e., west of) " the Fair Promontory. ... If Romans land in the parts of Sicily belonging to Carthage. ... In Sardinia and in Libya, no Roman shall do trade, or found cities, (or land) longer than is needed to take on provisions and repair his ship. If he is driven there by a storm, he shall depart within five days," and so on.4

At the end of the fourth century, Rome made a treaty with the great Greek colony of Tarentum; "an article in it formally forbade the Roman fleets to pass the Lacinian promontory."1 So Roman vessels were already sailing about the Tyrrhenian Sea and going through the Strait of Messina.

Inside Italy itself, Roman trade had extended into one district after another with her political dominion. It followed the chief roads which ran south, like the Appian Way, which was built as early as the end of the fourth century, or east and north-east, like the Latin and Flaminian Ways, or northwest, like the Aurelian Way. These roads, on which many colonies had been founded, were of as great value economically as strategically.

Another characteristic sign of the economic development of Rome from the middle of the fourth century onwards was the appearance at that time of an official coinage. Hitherto, since the primitive days of barter, the Romans had employed the method of weighing metal. Æs rude consisted of lumps of copper unadorned with any effigy or stamp; sales were said to be effected per ces et libram, " by copper and scales." A method of exchange as rudimentary as this became quite insufficient when the economic life of Rome depended on more highly civilized peoples like the Greeks, whose colonies in Great Greece and Sicily had long used coins which were convenient and much appreciated. Accordingly, the Roman State struck bronze and silver coins. The first bronze coins were of various values—the primitive asses which weighed a Roman pound and coins representing multiples and fractions of the pound. The silver coin, which was at first intended solely for military and commercial purposes in southern Italy, was a two-drachma piece of the type then current in Campania, and was minted at Capua. These Roman didrachms, which weighed about 7-5 grammes of silver, could doubtless be exchanged against three copper asses each weighing a Roman pound—i.e., 327 grammes. The disadvantages of this partly dual system were perceived fairly early, and after various experiments, into the details of which we need not enter, and reforms necessitated by fluctuations in the market price of copper in Rome, a new system was adopted in 269 B.C. The Roman pound of 327 grammes was taken as a basis, with its division into 12 ounces and 288 scruples. The copper unit was the as of 2 ounces or 48 scruples; the silver unit was the denarius of 4 scruples, which roughly corresponded to the Athenian drachma. A silver denarius was worth 10 copper asses. Copper coins representing fractions of the as were struck, and also a small silver coin equal to a quarter of a denarius, called the sesterce.

Rome now possessed an instrument of exchange which greatly promoted her trade. The innovation was especially important to her economic life in that it coincided with the extension of her territorial and political power, principally in the south of Italy, that is, in the region which contained the busiest markets with which she dealt. Besides, the appearance of a coinage which was easy to handle and easy to exchange with current Greek coins made a great difference to commercial transactions. Sales, purchases, and transit operations were greatly stimulated; there were even financial crises, created by the much more active circulation of coin.

But these were only passing troubles, mainly due to the inexperience of the magistrates of the Republic in financial matters. The great economic consequence was the development of movable wealth in Rome. Formerly, when the census was taken and the citizens were divided into classes and tribes, landed property alone had been taken into account. In 312, when Appius Claudius was elected Censor, he took statistics of movable capital, and his successors did not dare to undo his work. It was an absolute revolution in law; it was nothing less than " the entrance of movable wealth into political life."1

Another result of the conquests of Rome, no less fruitful from the economic point of view, was the fiscal organization of the ager publicus. In theory, the territory of the defeated and conquered cities belonged to Rome. We have seen above that part of this territory was sold, leased out, or conceded to the first occupier, but it was only to Roman citizens. Another part of the territory could be distributed to colonists, Roman or Latin. Another part, finally, was left to the former owners, grouped in a municipium, a prefecture, or an allied city, but on condition that they paid tribute (vectigal) to Rome. Moreover, to meet the often considerable expenses imposed on Rome by the frequent, almost uninterrupted wars in which she conquered the peninsula, even Roman citizens

MAP V.—ITALY UNDER THE ROMAN REPUBLIC.

had to pay a tax, the amount of which was assessed according to their total resources. For a long time the authorities based their assessment on landed property alone; movable wealth was included from the censorship of Appius Claudius in 312 B.C. Lastly, customs are proved to have been established on the frontiers of Roman territory, perhaps in the Royal period and at any rate in the first centuries of the Republic.1 Roman citizens, Latins, and Italian subjects and allies were all alike subject to these customs-dues or portoria. To collect all these direct and indirect taxes, the proceeds of the sale and hire of land, the rent from conceded land, and customs-duties, the State set up a fiscal organization in which the system of " farming " figured largely. This was the beginning of an evolution which was at first mainly financial, but afterwards had a considerable influence on the economic life of Rome and the whole Roman world.

We have now reached the moment at which Rome, the capital of an Italy united under her rule, was about to enter into conflict with Carthage. The stake for which they would fight was the supremacy of the Western Mediterranean. At the same time, Rome began to interfere in Greece and the East. For about two hundred years, in a series of wars in which she would not meet witli uninterrupted success but would always obtain the final victory, she would collect the whole ancient world under her sway, and would establish the unity of the Mediterranean for her own benefit. From being urban and regional, her economic life would become, if one may use the words regarding antiquity, international and world-wide. Here, again, the economic history of the Roman State would be determined, like her social evolution, by foreign affairs.

1 For the principal parts of this chapter I have chiefly made use of A. Piganiol, Essai sur les origines de Rome, Paris, 1917, and L. Homo, Primitive Italy, London and N.Y., 1027, in which very many works of specialists are mentioned and used; cf. LXXII, PP- 64 ff.; LXXVII, passim; LXXIX, pp. 31 ff., 241 ff.; LXXX, passim.

1 See above, pp. 24 ff.

1 M. Piganiol seems to say that it was: " The Sieels were a people of agriculturalists. . . . The Ligurians were a race of peasants who tilled the ground and buried their dead " (LXXXI, pp. 11-12). M. Homo, on the contrary, makes agriculture first begin with the Copper Age (LXXIII, English p. 29).

2 LXXIII, English pp. 26-29.

3 Ibid., English p. 32.

1 LXXIII. English pp. 32-33.

2 LXX. passim

3 LXXIII, English pp. 38 ff.

4 LXXXI, pp. 24 ff.

5 LXXIII, English p. 27.

1 LXXIII, English pp. 159-60.

1 R. de la Blanchére, Un Chapitre d'histoire pontine, passim. The author of this remarkable work nowhere mentions the Etruscans; but there is good ground for believing that the " cunicular drainage " described in such detail was done or inspired by them; cf. XVII, s.v. " Cuniculus."

2 LXXIII, English p. 110.

1 One centre of the Etruscan metal industry seems to have been Arretium. In 205, when Scipio was starting for Africa, Arretium provided him with 3,000 shields, 3,000 helmets, 50,000 darts, javelins, and long pikes, besides axes, picks, scythes, etc. (Livy, xxviii, 45).

1 LXXIII, English p. 75.

1 Ibid., English p. 84.

2 LXXV, pp. 24 ff.

3 LXXIII, English p. 96.

1 LXVIII, p. 48.

1 LXVIII, pp. 80 ff.

2 LXIX, pp. 29, 39.

3 LXXV, pp. 184 ff.

4 LXIX, pp. 62 ff.

5 LXXV, pp. 143-44.

1 LXXV. PP. 181 ff.

2 See above. pr., 201-2; LXIX. p. 30.

3 LXXIII, English p. 176.

4 Cf. above, pp. 201-2.

1 LXXIII, English p. 203.

1 LXVIII, pp. 109 ff., 118.

1 LXXIII, English pp. 238-39.