). In the postwar period, Taiwan’s assigned passive position was taken for granted and depreciated as such in historical reviews. As a result, scholarly inquiry into this period was hindered.

). In the postwar period, Taiwan’s assigned passive position was taken for granted and depreciated as such in historical reviews. As a result, scholarly inquiry into this period was hindered.A PERSPECTIVE ON STUDIES OF TAIWANESE POLITICAL HISTORY

Reconsidering the Postwar Japanese Historiography of Japanese Colonial Rule in Taiwan

It is well known that in the 1980s, when Taiwan underwent significant political changes, Taiwanese history suddenly began to generate a great deal of domestic and international academic interest. Particularly in Taiwan considerable time and material resources have been invested in this field of study.

It is worth noting that prior to this, however, the Japanese colonial period received relatively little academic attention (Chang 1983:15–16). This was the result of both historical and political factors. Most historians of the subject have hurriedly explored merely the frequent shifts of political rulers and have come to the premature conclusion that Taiwanese history is but “the process of development of peoples of various ethnic origins coming from outside” (Wu 1994:229–230). Such historical evaluations of Taiwan actually privilege the viewpoint and the values not of the ruled but of the ruling class. Given this historiographical trend, we can say that Taiwanese history in the period of Japanese colonization has been “doubly exploited” (Wu 1994:230), in that “Taiwan” in the period of Japanese colonization was forced into a passive position and identified as merely a stage in the “Empire’s South Advance” (teikoku nanshin  ). In the postwar period, Taiwan’s assigned passive position was taken for granted and depreciated as such in historical reviews. As a result, scholarly inquiry into this period was hindered.

). In the postwar period, Taiwan’s assigned passive position was taken for granted and depreciated as such in historical reviews. As a result, scholarly inquiry into this period was hindered.

Studies on the history of Taiwan in the colonial period were undertaken primarily by Japanese academics in the postwar period. Although there sometimes are expressed in Japan’s mass media certain opinions that retrieve the past from the viewpoint of the colonizer, only a few such discourses exist, and these among academics. More common, however, are scholars who have tried hard to overcome such viewpoints and historical perspectives. These studies, however, are far from being proof that “Taiwanese history” has itself become a recognized academic subfield in history. This is because the previous scholarship constitutes, in practice, the study not of the modern history “of Taiwan itself,” but of “Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan”; that is, Taiwan in this period is only insofar as it is a part of the modern history of “Japan.” To be sure, studies regarding Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan are not without significance. Indeed, they form a necessary element in the designation of modern Taiwanese history as a legitimate field of study. However, the currently received approach cannot be considered a comprehensive history of modern Taiwan: several Taiwanese scholars have made these observations (Wu 1983:18; Ka 1983:25). What then is the study of modern Taiwanese history? What kind of relationship should operate between the history of modern Taiwan and the history of Japanese imperialism/colonialism in Taiwan?

I begin this paper with a critical revisit to my previous work and attempt to evaluate what analytic mode such a historical approach might have and to what extent a constructive relationship could be bridged between the two approaches mentioned above. The resource materials for the establishment of my working hypothesis are mainly my own works; thus, this paper has to be subtitled “reconsidering the postwar Japanese historiography of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan.”

POLITICAL DYNAMISM IN THE TRANSFORMATION OF COLONIAL POLICIES: HARUYAMA MEITETSU’S “MODERN JAPANESE COLONIAL RULE AND HARA TAKASHI”

I have addressed the necessity of having a research perspective on the political history of Japanese colonialism in a co-authored book, The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, published in 1980 (Wakabayashi and Haruyama 1980). This perspective was fully developed in Haruyama’s article “Modern Japanese Colonial Rule and Hara Takashi  [also known as Hara Kei]” therein. Here I would like to review Haruyama’s work in order to determine in what ways this perspective might be useful to the current study.

[also known as Hara Kei]” therein. Here I would like to review Haruyama’s work in order to determine in what ways this perspective might be useful to the current study.

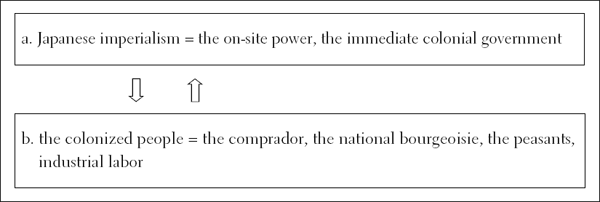

Before we wrote The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, studies of colonial politics focused mostly on individual cases of resistance or on the nationalist movement in history. Perhaps we can put the issue in bolder, if not too reductionist, terms: these previous studies adopted an analytic framework that, based on a theory of binary oppositions, pitted “Japanese imperialism” against “the colonized people.” This focus on opposition generated two noteworthy results. First, these studies equate Japanese imperialism with the on-site colonial authority (the colonial authority that encounters, first hand, the resistance and opposition of the colonized). Second, these studies, mostly based on Marx’s theory of class, have identified the colonized people with different class categories and have treated these classes’ interactions with the on-site colonial authority. In so doing, these studies amount to a history of oppression and resistance that, as diagrammed in figure 1.1 below, is based on an old analytic mode: the problem consciousness as it relates to studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism.

FIGURE 1.1 Old mode: The problem consciousness in studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism

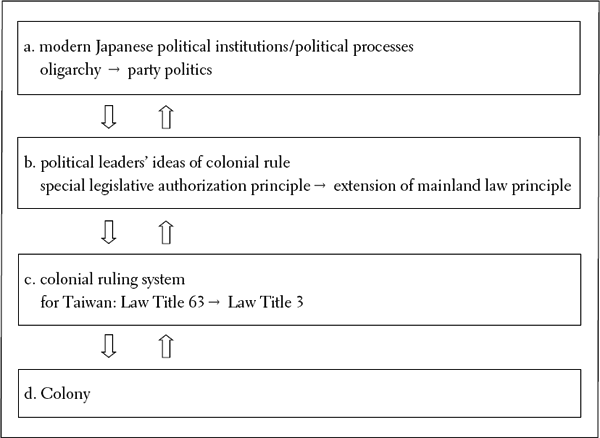

Haruyama has deviated from this old analytic mode. In previous studies based on the old mode, “although each individual colonial institution was mentioned respectively,” wrote Haruyama, “studies of the entire system of Japanese colonial rule are still lacking.” Thus, Haruyama continued, “this lack hinders our understanding of what political position the on-site colonial rule occupied within the entire Japanese state system,” and “it seems as though there is no relation between the development of Japan’s mainland political structure and its colonial rule” (Haruyama 1980:1). In order then to clarify the dynamic relations between the political history of Japan proper and the wider history of imperial Japan, Haruyama focused on a political leader, Hara Takashi, who played a significant role in the development both of mainland Japan’s political history and of imperial Japan’s colonial history. Haruyama’s resulting findings are diagrammed in figure 1.2.

A longtime leader of the political party Rikken Seiyukai  (in existence since the late Meiji period), Hara Takashi transformed modern Japan’s political system from an oligarchy to a party-based democracy (see level a in fig. 1.2). He skillfully managed to play the politics of compromise and resistance with the existing oligarchy and helped install party-politics in the accepted political system. Through his efforts, Japan witnessed the successful establishment not only of the Imperial Diet (teikoku gikai

(in existence since the late Meiji period), Hara Takashi transformed modern Japan’s political system from an oligarchy to a party-based democracy (see level a in fig. 1.2). He skillfully managed to play the politics of compromise and resistance with the existing oligarchy and helped install party-politics in the accepted political system. Through his efforts, Japan witnessed the successful establishment not only of the Imperial Diet (teikoku gikai  ) as a state institution in which political parties functioned, but also of a party-based system that played a key role in the entire state system. In the midst of the Taisho period, Hara Takashi became prime minister of the first civil, party-organized cabinet in Japanese modern history. Immediately after he organized his Seiyukai cabinet, the First World War ended, and half a year later the March 1 Independence movement took place in Korea. Japan’s colonial ruling system experienced the profound effects of these events.

) as a state institution in which political parties functioned, but also of a party-based system that played a key role in the entire state system. In the midst of the Taisho period, Hara Takashi became prime minister of the first civil, party-organized cabinet in Japanese modern history. Immediately after he organized his Seiyukai cabinet, the First World War ended, and half a year later the March 1 Independence movement took place in Korea. Japan’s colonial ruling system experienced the profound effects of these events.

FIGURE 1.2 New mode: The problem consciousness in studies of the political history of Japanese colonialism

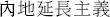

In his article, Haruyama traced the development of Hara Takashi’s beliefs and political career and found that, long before becoming a politician, he had developed a model for Japanese colonial rule that was later to be called “the principle of the extension of mainland law” (naichienchoshugi  ). Haruyama also discovered that Hara Takashi stood firmly by this idea when he engaged in debates over colonial policymaking within the Meiji government.1 On the difficulties surrounding the policy of the special authorization of colonial jurisdiction (the “Problem of Law Title 63,” rokusan mondai

). Haruyama also discovered that Hara Takashi stood firmly by this idea when he engaged in debates over colonial policymaking within the Meiji government.1 On the difficulties surrounding the policy of the special authorization of colonial jurisdiction (the “Problem of Law Title 63,” rokusan mondai  —that is, the controversy over the special legislative authority assigned to the governor-general of Taiwan), and on the problem concerning colonial administrative institutions (whether the military or the civil governor should be in charge of the colonial administration), Hara Takashi, with his party’s support, used political means to reduce the degree of legal exceptions (for example, authorization of the governor-general’s special legislative authority) and of political exceptions (for example, the appointment of a military governor-general) in the already oligarchized colonial administration. In short, Hara embraced colonial administration insofar as it operated within the domain of the mainland’s party-politics. After becoming prime minister, he put an end to the appointment of the military governor-general and reduced the scope of the legislative authority that had found its way to the governor-general (as seen in the enactment of Law Title 3).

—that is, the controversy over the special legislative authority assigned to the governor-general of Taiwan), and on the problem concerning colonial administrative institutions (whether the military or the civil governor should be in charge of the colonial administration), Hara Takashi, with his party’s support, used political means to reduce the degree of legal exceptions (for example, authorization of the governor-general’s special legislative authority) and of political exceptions (for example, the appointment of a military governor-general) in the already oligarchized colonial administration. In short, Hara embraced colonial administration insofar as it operated within the domain of the mainland’s party-politics. After becoming prime minister, he put an end to the appointment of the military governor-general and reduced the scope of the legislative authority that had found its way to the governor-general (as seen in the enactment of Law Title 3).

Through this case study of political leader Hara Takashi’s ideas and career (the b level of fig. 1.2), Haruyama was able to clarify the dynamic relation between the political system of modern Japan and the colonial ruling system (the c level of fig. 1.2). In other words, the new analytical framework that Haruyama adopted (fig. 1.2) identified the existence of specific political dynamics in the formation of colonial policy in modern Japanese history—an insight exceptionally lacking in the previous framework (see fig. 1.1), which was based on binary oppositions. Hence, Haruyama has helped create a new conceptual space for studies of modern Japanese colonialism, a space in which the history of the mother country’s politics becomes closely tied up with the history of modern Taiwan.2

There is, however, no doubt that such research belongs to “the field of modern Japanese history, not the field of Taiwanese history” (Wu 1993:18). As mentioned above, Haruyama’s intent was to overcome the received notions—the unexamined assumptions—of the old research mode, which he did, but he has not explored the new research mode in detail. For this reason, we can say that Haruyama’s work has contributed mostly to a modification of the exterior environment and thus of the historical context that informs studies of Taiwanese political history during Japanese colonial rule.

PRACTICING A CONTROL SYSTEM THROUGH EXCHANGE AND MEDIATION: A WORKING HYPOTHESIS REGARDING THE “TAIWANESE NATIVE LANDED BOURGEOISIE”

In the light of the discussion in the previous section, I would like here to explore further the d level in figure 1.2, that is, questions concerning the local structure of colonial politics in Taiwan. I articulated a working hypothesis regarding “Taiwanese native landed bourgeoisie” (Taiwan dōchaku jinushi shisan kaikyū

) in two case studies: “The Colonial State and Taiwanese Native Landed Bourgeoisie: Questions Surrounding the Establishment of the Taichung Middle School, 1912–1915” (Wakabayashi 1983b) and “Taisho Democracy and the Petition for the Establishment of a Taiwan Parliament: Japanese Colonial Politics and the Taiwanese Anti-colonial Movement” (Wakabayashi 1983a).

) in two case studies: “The Colonial State and Taiwanese Native Landed Bourgeoisie: Questions Surrounding the Establishment of the Taichung Middle School, 1912–1915” (Wakabayashi 1983b) and “Taisho Democracy and the Petition for the Establishment of a Taiwan Parliament: Japanese Colonial Politics and the Taiwanese Anti-colonial Movement” (Wakabayashi 1983a).

The former is an examination of why the local apparatus of the Japanese empire (that is, Japan’s governor-general government in Taiwan), after violently suppressing riots that had spread over the entire island and after establishing the administration in the early stages of colonization, had no choice but then to negotiate with the Taiwanese upper classes in order to maintain power. The colonial government regarded the Taiwanese upper classes, which I conceptualized as the “native landed bourgeoisie,” as an important target of its political policies.

In exploring this working hypothesis about the existence of Taiwan’s “native landed bourgeoisie” to better depict the nature of colonial politics, I looked at Taiwanese educational demands as seen in the movement to establish the Taichung Middle School, which lasted four years, from 1912 to 1915, and which was once described by Yanaihara Tadao as “the first shot of the Taiwanese Nationalist movement” (Yanaihara 1988:190). In order to draw out the contours of the political process surrounding the establishment of the Taichung Middle School in 1915, I highlighted Governor-General Sakuma Samata’s decision to accept the Taiwanese upper classes’ petition for “the establishment of a middle school in Taiwan on the same level as middle schools in domestic Japan.” It is interesting to note that, in the end, this educational petition was only partially realized after negotiations with Tokyo.

The second case study listed above incorporated both Haruyama’s research findings and the idea of a “native landed bourgeoisie” in Taiwan and is an exploration of the political process underlying requests to mainland Japan for the establishment of a Taiwan parliament (1921–1934). This movement for home rule was in fact a civil rights movement launched by Taiwanese intellectuals on Japan’s domestic central political stage in a period called the Taisho Democracy, which spanned from the mid-Taisho period to the early Showa period.

Before we look at the case studies in detail, let us consider what is meant in this working hypothesis by the designation native landed bourgeoisie. The term refers to those members of Taiwan’s social upper classes (including property owners like local strongmen, gentry, landlords, and wealthy businessmen) who could trace their roots to the former late Qing period and who were historically transformed “during the process whereby Japan consolidated its colonial domination—that is, a process whereby Japanese political power and capital imposingly launched a top-down colonialist modernization project” (Wakabayashi 1983b:6). There were two historically significant conditions for the emergence of this “class”: the uneasy securing of public safety in the seventh year of Japanese rule and the land survey commission’s goal of clearing up the complicated landed property relationships that characterized regulation of the island’s cultivated land.

In securing the public safety, the native militias, which were privately patronized under the local strongmen, were either destroyed by superior Japanese military and police forces or disarmed. Those gentry who had received higher honor-titles in the Qing civil examinations, and who felt a deep commitment to the Chinese dynastic order, had mostly returned to China in the moment of territorial transition in 1895. Those local gentry who stayed in Taiwan lost the political influence that had been guaranteed by the Qing authority in local societies.

The land survey commission eliminated the existing custom of shared land-ownership (the one-land, two-owners issue, ichiden ryōshū ) by rescinding the patent (ta-tsu

) by rescinding the patent (ta-tsu  ) rights, by ensuring that land ownership would go to the actual proprietors (hsiao-tsu holders

) rights, by ensuring that land ownership would go to the actual proprietors (hsiao-tsu holders  ) and by protecting their right to collect land rents. Although the Japanese colonial government through these policies, along with setting up an official monopoly, determined the colonial revenue, the actual landowners, who were natives of the island, received legal protection of their landed property from the new regime (the Japanese colonial government) and were thus allowed to keep collecting high rents from their peasant tenants.

) and by protecting their right to collect land rents. Although the Japanese colonial government through these policies, along with setting up an official monopoly, determined the colonial revenue, the actual landowners, who were natives of the island, received legal protection of their landed property from the new regime (the Japanese colonial government) and were thus allowed to keep collecting high rents from their peasant tenants.

This confluence of policies and practices allowed Taiwan’s upper classes from the late Qing period to become the people who “had fame and property” in the early period of Japanese colonization; in other words, their economic bases were protected by the new regime, and to some extent their social influences were also maintained accordingly (Wakabayashi 1983b:7–8).

What kind of relationship did this native landed bourgeoisie cultivate with the Japanese colonial government? In the first place, the Japanese authority stripped the old Taiwanese leading stratum of their ostensible power and authority. However, the Japanese authority was unable to root out the existing economic bases of these Taiwanese and even paradoxically protected their interests by means of modern law and public safety. Furthermore, the Japanese colonial authority in Taiwan also took advantage of these people who possessed “fame and property” by using their social influence to smooth Japan’s domination of the island. This means that the colonial authority, when deciding where in the hierarchy to assign individual Taiwanese, judged them in relation to their property, fame, and degree of willingness to collaborate. These criteria were used to assign Taiwanese to the specific positions, for example, of village head, local district administrative assistant, and hokō leader, each of which was designed to assist the local police station. Even more prestigious was the position of district consultant in the local administration, the holders of which would be invited as honored participants to official banquets and nominated as receivers of the “gentry certificate” (shinshō  ) or other honors.

) or other honors.

By so doing, the new Japanese colonial authority successfully took the place of the old Qing mandarins in redistributing the resources of power and authority. It was of course a prerequisite that these men of “fame and property,” as receivers of the privileges and honors authorized and distributed by the Japanese, must pose no threat to Japanese rule. However, to maintain their influence in local society, these men also had to accommodate local interests and sentiments. This adjustment to local interests took place in the context of colonization and might turn, at certain moments, into a source of opposition to Japanese rule. Moreover, in their adjustment to the modernization that took place under colonial rule, some of these privileged Taiwanese learned afresh the essence of colonial constraints on their sociopolitical potential and, in response, gradually accumulated economic power by collecting higher rents from their tenants and by investing in their children’s education.

No matter how the colonial authority constantly created conditions of dependency—perhaps best exemplified in the nature of the “collaborationist gentry” (gōyō shinshi  )—we can still see the possibility of resistance, as a force emerged from within this upper social stratum to limit the growth of the native bourgeoisie itself and even to oppose Japanese domination (Wakabayashi 1983b:9).

)—we can still see the possibility of resistance, as a force emerged from within this upper social stratum to limit the growth of the native bourgeoisie itself and even to oppose Japanese domination (Wakabayashi 1983b:9).

This research hypothesis, depicting the nature of the native landed bourgeoisie, thus formed the basis for the two case studies mentioned above. In the first (1983b), my investigation of the establishment of Taichung Middle School, I looked up board members, donators, and honor-title holders in the Taiwan retsushin den ( , a collective biographic dictionary of people who received gentry titles from the colonial government), and discovered that the majority of petitioners involved in the movement to establish the school were basically native landed bourgeoisie. The colonial archive and Taiwan nichinichi shinpō (

, a collective biographic dictionary of people who received gentry titles from the colonial government), and discovered that the majority of petitioners involved in the movement to establish the school were basically native landed bourgeoisie. The colonial archive and Taiwan nichinichi shinpō (

, Taiwan daily news) provided resource materials to show the decision-making process underlying the establishment of the school. I argue that Taiwan’s governor-general, Sakuma Samata, was at that time commencing what he considered to be the most significant task within his purview, the “Five-Year Project for the Pacification of the Savage Territory” (which became, in fact, a series of wars of conquest waged against the indigenous tribes in northern Taiwan’s mountainous regions). Sakuma was critically in need of assistance from the native landed bourgeoisie because of the difficulties arising from fiscal problems and the mobilization of military aid. In return for their assistance, Sakuma promised to establish a middle school “on the same level as middle schools in domestic Japan.”

, Taiwan daily news) provided resource materials to show the decision-making process underlying the establishment of the school. I argue that Taiwan’s governor-general, Sakuma Samata, was at that time commencing what he considered to be the most significant task within his purview, the “Five-Year Project for the Pacification of the Savage Territory” (which became, in fact, a series of wars of conquest waged against the indigenous tribes in northern Taiwan’s mountainous regions). Sakuma was critically in need of assistance from the native landed bourgeoisie because of the difficulties arising from fiscal problems and the mobilization of military aid. In return for their assistance, Sakuma promised to establish a middle school “on the same level as middle schools in domestic Japan.”

In my other study (1983a), dealing with the petitionary movements for the establishment of a Taiwan parliament, I examined this movement’s strategy: that is, how the colonized people sent their petition to the mother country’s parliament, and how their demand for civil rights and home rule was dealt with in the domestic politics of the Taisho Democracy period. This is indeed a research perspective echoing the above-mentioned “politics of Japanese colonialism.” In addition, this paper deals with the hypothesis concerning the native landed bourgeoisie in order to analyze the movement’s participants and their relationship to Japanese colonial power. By rigorously investigating the petitioners’ social backgrounds and the leaders’ activities (preserved in the files on this petition movement in the colonial police’s archive), I proved that Taiwanese “new intellectuals”—who were the first generation of modern intellectuals, Han Taiwanese, and alumni of Japanese colonial education—had teamed up with some native landed bourgeoisie to make possible this petitioning movement (Wakabayashi 1983a:24–35).

Through these analyses, I was able to extract from the history of this movement insights into the colonial politics on the island and pointed out that “such historical phenomena (the coalition between the new intellectuals and some native landed bourgeoisie) tell us that, under the conditions of (a) the further development of Japanese monopoly capitalism, (b) modern ideologies’ influences over the offspring of native landed bourgeoisie, and (c) a growing nationalistic consciousness, the native landed bourgeoisie, who had earlier played the role of political and economic mediators in the context of Japanese colonization, disintegrated; some became new emerging compradors and some Nationalists” (Wakabayashi 1983a:38–39). Thus, “the Japanese authority had encountered an important two-fold political problem in its effort to strengthen Japan’s relationship to its colony in the post-First World War era: (a) how, given time constraints, to handle the oppositional force that emerged in the petitionary movement for the establishment of a Taiwan parliament and (b) how to reorganize the colonial ruling structure in which these oppositionists were still made to play the mediating role for colonial rule. This was a crucial political problem that, in the post-First World War era, plagued the on-site colonial authority as it attempted to restructure the unity of Japan and its colony. This problem surfaced because the colonized representatives directly petitioned the Japanese central government, demanding that a Taiwan parliament should be established in the colony to meet the best interest of the colonized. Consequently, this problem did not concern merely the colonial government in Taiwan” (Wakabayashi 1983a:38).

My two papers led then to findings on two different levels. On the first level, there exist some relationships of political exchange between, on the one hand, the governor-general government that constituted the on-site representative of Japanese colonialism in Taiwan and, on the other hand, native Taiwanese men of “fame and property” in Taiwanese society. One can see this exchange relationship operate in the establishment of Taichung Middle School, for which the colonial government had answered Taiwanese educational demands in exchange for fiscal and manpower assistance at a time when the Japanese colonizers were commencing a war of conquest against the mountainous indigenous tribes. This was surely an uneven exchange. When the school was eventually established, the Taiwanese had to raise funds by themselves, and what they got from the colonial government in return for their assistance during the war was merely a validating piece of paper. (Even the promise that Taiwanese middle schools would be “on the same level as middle schools in domestic Japan” was not kept.) What the colonial government offered according to this give-and-take condition was but a rent in the form of pronouncements naming these Taiwanese franchisees in the colonial monopolistic businesses.3

In addition, the exploration of the petitioning movement for the establishment of a Taiwanese parliament reveals that this movement was made possible through a coalition between the new intellectuals and some native landed bourgeoisie. The explanation of this historical phenomenon hinges on the fact that Taiwanese elites as men of “fame and property” were not satisfied with their exchange relation with the colonial authority. There were thus some native elites who rejected this exchange relationship, which had been defining the nature of their own power, and who took a stand that aligned them with Taiwan’s social masses. This stand in turn facilitated the emergence of Taiwanese anticolonial nationalism.

I suggest that these findings can contribute to the development of a working hypothesis concerning the politics of Japanese colonialism in Taiwan. That is, a ruling mechanism exists at the receiving end of the exchange relationship between the Taiwanese colonial government as the on-site manifestation of Japanese imperial power and the native Taiwanese men of “fame and property” in Taiwanese society. This mechanism and its relation to a number of component elements in Taiwanese society constituted the primary content of politics in colonial Taiwan. It goes without saying that what the Japanese authority required was not solely money from those men of “fame and property” but also—and of greater importance—their attitude of collaboration. The colonial authority hoped that, through collaboration among these Taiwanese, enacted in certain exchanges, Taiwanese elites’ social credits could be used to influence the common people.

The aim set by the colonial authority was to transform this collaboration into a force that would render the common colonized people more obedient. And if this aim were not easily achieved, their collaboration would at least render the Taiwanese silent subordinates. In short, the colonial government intended to use the exchange as a way to effectively impose the prestige of the colonial power throughout Taiwanese society. The mediating mechanism of exchange must also have functioned well in Japan’s use of the Hoko system to facilitate the establishment of a full-scale police force network. It can be thought of as a mechanism that controls through exchange and mediation.

On the second level, men of “fame and property” who embraced, or were compelled under pressure to embrace, this control mechanism of exchange and mediation were native landed bourgeoisie. To be sure, I have some reservations over the use of this conception, and regard it only as a working hypothesis. Whether these people’s real conditions of existence can be correctly described by a category such as native landed bourgeoisie requires more empirical research.

However, there are some points still to be emphasized here. First, the Japanese authority wanted to incorporate some people who possessed resources of various sorts into the control mechanism of exchange and mediation; whether these people truly wished to participate in that relationship is another issue. The situation in fact differed greatly from case to case. Some of those who possessed “fame and property” did not get involved, whereas some who were in the process of accumulating fortunes collaborated extensively with the Japanese. This is an easily overlooked problem if approached from only the perspective of the Japanese ruler, as found in the existing formulation of “Japanese colonialism in Taiwan,” but is nonetheless a necessary consideration in studies of Taiwanese modern political history. The choices for the elites were many: to be involved or not, to be a volunteer or to be forced, to quit or to stay, to silently reject this exchange and mediation mechanism or to openly attack it—all these choices and their accumulation constituted, quite precisely, the politics of the Taiwanese people in the colonial context.4 To explain the process in which specific people made their own “fortune” and “fame” under colonial rule is to study a set of circumstances from the perspective of political economics or political science, while to inquire into the real conditions of existence as they are revealed in the accumulation of these individual choices is to study the politics of colonialism from the perspective of historical studies (say, studies in political history). These two perspectives stand in relation to each other but are not identical.

A second point is that the definition of what were considered “useful” resources to be managed in the control mechanism of exchange and mediation changed over time, as Japanese colonization progressed. For example, people involved in the exchange mechanism used the social resources that they had acquired through tradition as a tool with which to effect colonial education reform; and their children, possessing new cultural resources that they had received from this new colonial education, encountered this already politicized exchange mechanism and actively contended with it—and what had been regarded as exchangeable in the give-and-take relation of their fathers’ period was no longer current.

Both I (Wakabayashi 1983c) and Wu Wen-shin (1992) have pointed out that it is exactly this changing set of terms that well explains why, from the 1920s onward, the Taiwanese new intellectuals heavily criticized personnel problems in the local administration. As the content of useful resources changed over time, the choices Taiwanese people made in the exchange and mediation mechanism changed accordingly. In 1935 the colonial government put a limited local election into practice and, by co-opting native elites through this election system, restructured local politics. This development also reflects the changes taking place in the conditions of exchange between the colonial authority and the native society.

As Taiwan’s economic development continued and more people received a formal education, the population involved in the exchange mechanism became larger in number. As more and more Taiwanese people who possessed certain resources became candidates in this one-to-many exchange relation that was managed by the colonial government as a means of social control, the give-and-take mechanism eventually faltered. As a result, another mechanism—by control through participation and incorporation—featuring more objective standards by which to filter its targets was later introduced. And, indeed, when this “later time” met the moment in which the colonial government had to mobilize people on behalf of the war effort, this mechanism came to operate at an unprecedented level (Mitani Taichirō1993).

PRACTICING THE CONTROL SYSTEM THROUGH DISCIPLINING AND TRAINING: WAKABAYASHI MASHAHIRO’S “THE IMPERIAL VISIT OF THE CROWN PRINCE TO TAIWAN IN 1923” (1992A)

The state form that, in prewar Japan, governed colonial Taiwan was a constitutional monarchy, that is, an emperor-system state (tennōsei kokka  ), in which the emperor himself represented the mighty sovereign. Throughout the history of this emperor-state’s rule over colonial Taiwan, the emperor never visited (gyoko

), in which the emperor himself represented the mighty sovereign. Throughout the history of this emperor-state’s rule over colonial Taiwan, the emperor never visited (gyoko  ) the island. Only the crown prince (tōgū

) the island. Only the crown prince (tōgū  ), the Taishō emperor’s prince Hirohito (later the Showa Emperor), had visited (gyokei

), the Taishō emperor’s prince Hirohito (later the Showa Emperor), had visited (gyokei  ) his colonies of Taiwan and Karafuto. Because the residents of Karafuto were in fact early Japanese immigrants, Crown Prince Hirohito’s Taiwan visit (Taiwan gyōkei,

) his colonies of Taiwan and Karafuto. Because the residents of Karafuto were in fact early Japanese immigrants, Crown Prince Hirohito’s Taiwan visit (Taiwan gyōkei,

) in April 1923 can be seen as the only instance in which a member of the imperial royalty visited the colony. Crown Prince Hirohito was in fact a prince regent, because the Taisho emperor was ill at the time, and this situation had made Hirohito the de facto superior human symbol of the emperor-system. His imperial visit thus became the most important political event in the ruling of a foreign people at the time (Wakabayashi 1992a:87–88).

) in April 1923 can be seen as the only instance in which a member of the imperial royalty visited the colony. Crown Prince Hirohito was in fact a prince regent, because the Taisho emperor was ill at the time, and this situation had made Hirohito the de facto superior human symbol of the emperor-system. His imperial visit thus became the most important political event in the ruling of a foreign people at the time (Wakabayashi 1992a:87–88).

The imperial visit conducted by the crown prince as the human symbol of the emperor-system was composed of a series of imperial rituals and ceremonies (Tennō gishiki  ). This consisted of rituals of mutual presence, performance, and even demonstration between the imperial human symbol and his subjects. In “The Crown Prince’s Taiwan Visit of 1923 and the ‘Principle of the Extension of Mainland Law’ (Naichigenchoshugi)” (1992a), I tried to decipher the symbolic structure of Crown Prince Hirohito’s 1923 Taiwan visit by depicting the interaction in rituals and ceremonies between the emperor and his subjects as a scene of demonstration in which the emperor-system state exercised its symbolic power over the colony.

). This consisted of rituals of mutual presence, performance, and even demonstration between the imperial human symbol and his subjects. In “The Crown Prince’s Taiwan Visit of 1923 and the ‘Principle of the Extension of Mainland Law’ (Naichigenchoshugi)” (1992a), I tried to decipher the symbolic structure of Crown Prince Hirohito’s 1923 Taiwan visit by depicting the interaction in rituals and ceremonies between the emperor and his subjects as a scene of demonstration in which the emperor-system state exercised its symbolic power over the colony.

According to my research, this performance by the emperor, rarely seen in the history of Japanese colonialism, can be divided into three components: (1) a display of the ordering—the “authorization sealing” in which the “sacred stamp” is appended to the existing order; (2) a display of the civilizing—the “symbolic moral” of the human symbol of the emperor-system in which the emperor and the imperial family are seen as “the very foundation of civilization, the mighty origins of institution and learning,” enhancing the desirable Japanese process of modernization (that is, the emperor’s tour will provide the resources for imposing the civilizing mission on his subjects); and (3) a display of the mystifying—the crown prince’s official visit to the Taiwan shrine at which he worshiped an imperial kinsman, Prince Kitashirakawanomiya Yoshihisa, who had commanded, and died in, the war to conquer Taiwan in 1895; he also granted an gracious imperial remission to the prisoners of the Hsilai An incident (Seiraian jiken

). Each one of these invoked a corresponding set of symbolic actions, known as the rites of passage, the rites of conquering, and the rites of reconciliation.

). Each one of these invoked a corresponding set of symbolic actions, known as the rites of passage, the rites of conquering, and the rites of reconciliation.

Among these three symbolic ritual actions, the rites of reconciliation were more about the colonizer’s unilateral self-deception as a way to legitimize the past history of colonization; the rites of passage and the rites of conquering referred to the techniques used to directly connect the colonial society to the imperial political order. For example, for the rites of passage, when the crown prince visited an administrative institution, the hierarchical order that already existed in that institution would inevitably be emphasized in the spatial formation of the participants. The human symbol of the emperor-system presented himself in front of the display and appended his sacred seal to this order.

For the sacred seal to be granted in this way, however, the would-be approved display had to be indisputably in order. Thus, members of that institution were required to be kept in a state of high morale, and, by relying upon the suppressive force of police and public safety organizations, any undesirable action in the scenario of the display of the ordering had to be prevented in advance. Here one sees that the emperor, as the symbolic leader, and his visit functioned to approve the already well-regulated order. Some of the local Taiwanese leaders who possessed “fame and property” participated, or were forced to participate, in the system of control through exchange and mediation, as the previous section detailed, and were then relegated to subordinate positions in the display’s hierarchical spatial formation. Indeed, these participants stood still, waiting to “welcome” (hōgei

) the coming of the crown prince (Wakabayashi 1992a:102).

) the coming of the crown prince (Wakabayashi 1992a:102).

In the rites of conquering in the “display of the civilizing,” the crown prince—who embodied “the very foundation of civilization, the mighty origins of institution and learning”—was displayed in front of the masses (minshū  ); at the same time, the masses were gathered together and subjected to the powerful gaze of the crown prince (as the human symbol of the imperial sovereignty). Because the prince’s gaze could be downwardly conferred, the masses were also exposed to the gaze of many “middle instructors”; playing the role of the so-called little emperor (shotennō

); at the same time, the masses were gathered together and subjected to the powerful gaze of the crown prince (as the human symbol of the imperial sovereignty). Because the prince’s gaze could be downwardly conferred, the masses were also exposed to the gaze of many “middle instructors”; playing the role of the so-called little emperor (shotennō  ), they were components in the hierarchy of the state apparatus who presented and re-presented the emperor’s gaze on every level. In order to be displayed before the gaze of the sovereign, the masses had to faithfully embody the empire’s “loyal and virtuous subjects” (shūryōshinmin

), they were components in the hierarchy of the state apparatus who presented and re-presented the emperor’s gaze on every level. In order to be displayed before the gaze of the sovereign, the masses had to faithfully embody the empire’s “loyal and virtuous subjects” (shūryōshinmin

). The body of the masses was not a physical body as such but a culturally defined body, always wearing certain exterior garments and participating in certain rituals and ceremonies; the middle instructors worked to discipline and to train them. In the ritual of the display of the civilizing, schoolchildren and students were purposefully and systematically made to be present under the disciplining and training gaze of the crown prince (Wakabayashi 1992a:103–107).

). The body of the masses was not a physical body as such but a culturally defined body, always wearing certain exterior garments and participating in certain rituals and ceremonies; the middle instructors worked to discipline and to train them. In the ritual of the display of the civilizing, schoolchildren and students were purposefully and systematically made to be present under the disciplining and training gaze of the crown prince (Wakabayashi 1992a:103–107).

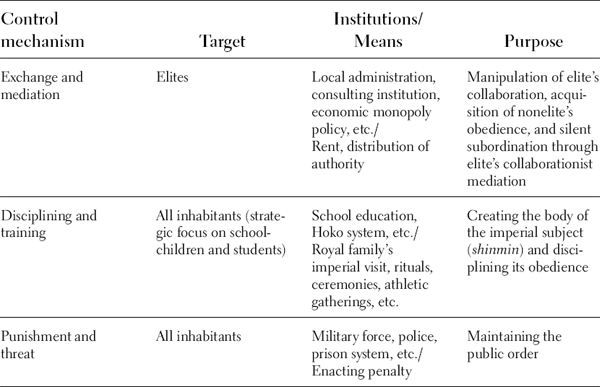

My article about the crown prince’s colonial visit discusses the ways in which in the moment of 1923, through the crown prince’s imperial visit, the Japanese emperor-system state symbolically recolonized Taiwan (see also Fujutani 1994: 57). By including a sectional drawing of this visit’s power mechanism, I was able to demonstrate the existence of the control system through exchange and mediation. At the same time, there was another form of control mechanism. This mechanism, not aimed primarily at the resourced elites but at all the inhabitants of the island (yet strategically targeting schoolchildren and students), made itself effective through the disciplining and training gaze delivered by the emperor and his agents (as the middle instructors) in a hierarchical top-down register. I call this the control system through disciplining and training.

Takashi Fujitani has demonstrated that the imperial-Nationalistic rituals and ceremonies—of which the emperor played the prime protagonist—designed and promoted by the Meiji leaders constituted a form of domination of the gazing. Two ways of visualization can be found in this domination of gazing: “the emperor of modern Japan becomes the transcendental subject by receiving the centripetal gaze from all his subjects to whom the existing internal differences was surmounted; on the reversing gaze, all national subjects in the empire, without considering their differences in places or classes, become visible under the sole, dominant and suffusing gaze of the emperor.” And, “if such attempt of visualization accomplished, the modern national subjects as being constantly self-positioned as the monitored objects would consciously emerge from the interior” (Fujitani 1992:141).

What we have called the control system through disciplining and training is the extension to the colony of what Fujitani calls the domination of the gazing in modern Japan. How this extension was made possible is of course an issue in modern Japanese history. How the modern national subjects emerged, or did not emerge, over the course of this extension is a historical question of significance in both modern Japanese history and modern Taiwanese history. Under the operation of this control system through disciplining and training, to what extent, if any, was the Taiwanese people’s “body” transformed into “Japanese subjects”? Did the differences revealed in the colonial transformation have something to do with inhabitants’ cultural and social differences (such as different ethnic backgrounds)? Can the interaction between the native cultures and this control system have successfully brought about the formation of the “Taiwanese identity”? If so, to what extent did it create modern Nationalistic subjects? All these questions should be investigated from the perspective of the modern political history of the Taiwanese people.5

CONCLUSION

The above review of Haruyama’s work has enabled us to locate the difference between studies of political history that concern Japanese colonialism in Taiwan and studies of political history that concern modern Taiwanese political history. In a reexamination of two of my earlier articles I explored the mechanism by which ruling power was exercised in colonial Taiwan, identifying two forms of control: exchange and mediation and disciplining and training. Nevertheless, I am well aware that, in the study of modern Taiwanese political history, more than a few questions have yet to be answered satisfactorily.

To be sure, the mechanism of colonial control had more than these two forms; indeed, one other form of the control mechanism is clearly identifiable: the colonial authority’s monopoly on violence, wherein punishment was exercised to keep the public order, and where the possibility of punishment was made visible and manifest. This control mechanism can be called control through the mechanism of punishment and threat. This is a necessary and intrinsic mechanism within the modern state’s exercise of power and accordingly guarantees the effectiveness of the two forms of control mechanism reviewed above. Therefore, questions concerning the historical process according to which the Japanese monopoly on violence in colonial Taiwan took root, collapsed, and finally yielded to another political regime—in short, questions concerning the military history of the Japanese colonization of Taiwan—should be embraced as a subfield in modern Taiwanese political history.

The discussion above can be summarized in the table below.

If the viewpoints stated above can be used to effectively analyze Taiwan’s political history under Japanese colonial rule, we should extend our analysis to the historical periods before and after the period discussed in this paper. That is, we should ask whether these three control mechanisms from the colonial period also existed in the late Qing period or in the postwar period. If not, was there any other mechanism that facilitated political control in these periods? When encountering such a control mechanism, what kind of resources did Taiwanese people use to negotiate with it? How did these negotiations then trigger a qualitative transformation of the control mechanism?

TABLE 1.1 Control Mechanisms in Colonial Taiwan

By asking questions like these, we may be able to achieve a proper understanding of historical continuity and discontinuity in Taiwanese political history. For example, we have asked how the economic transformation regarding foreign trade in Taiwan that took place during the rapid growth of the late Qing period changed the accepted power structure of society. Is there any difference between the dual clientism (Wakabayashi 1992b: chapter 3) or the dual structure of factional politics (Chen 1995: chapter 4) in postwar Taiwan under the Kuomingtang’s partystate regime and the control mechanism through exchange and mediation in the Japanese colonial period? Such reflections on other periods could deepen our understanding of the nature of Taiwanese politics under Japanese colonial rule.

NOTES

*Translated from the Japanese text by Chen Wei-chi.

1. Immediately after Japan took over Taiwan in 1895, the Japanese government set up a new provisional organization within the cabinet, the “Bureau of Taiwanese Affairs.” The bureau was under the direct control of the prime minister, Ito Hirobumi, and was aimed at setting some foundational principles for the rule of the colony. Hara Takashi, who then was vice-minister of foreign affairs, participated in this organization. He already had ideas on the project of Japanese colonial rule in Taiwan that were different from the principles already then in effect. He stated, “[We] should not treat Taiwan as a colony, even when there is some variety between Taiwan and Japan proper” and “The administrative institution in Taiwan should be as close as possible to the mainland’s, even to the point that there is no difference between them” (Haruyama 1980:23).

2. Wu Mi-cha has offered a concise introduction similar to Haruyama’s to the historical studies that followed (Wu 1993).

3. One interpretation of the function of such rent posits that “the state apparatus can use all kinds of policy tools to create contrived rents, including state monopoly, charter policy, import quota, government’s selective purchase, selective wealth redistribution, credit and foreign exchange preference, and so on; that is, the state apparatus can adopt selectively limitative or punitive legal regulations in order to enable a few producers to take advantage of markets and further expand their profits” (Chu 1989:139–140).

4. Wu Wen-shin’s study of “social leadership” (1992) and the “family history studies” recently current in Taiwan—such as Chen 1992, Hsu 1992, and Huang 1995—give important insight concerning the issue of Taiwanese politics under Japanese colonization.

5. Both Fujitani’s arguments (1994) and the findings of Taki Koji (1988)—on which I rely (1992a) for my understanding of “the gazing of disciplining and training” launched by the Tenno—are based on the theories of Michel Foucault.

REFERENCES

Chang Yen-hsien. 1983. “Introduction.” Special forum on the review and prospect of the studies of the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan history: Newsletter of Taiwan History Field Research 26.

Chen Tsu-yu. 1992. “The Yen Family of Keelung and Taiwan’s Coal Mining Industry Under Japanese Rule.” In Family Process and Political Process in Modern Chinese History 2. Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica.

Chu Yun-han. 1989. “Monopoly Economics and Authoritarian Political System.” In Taiwan Research Foundation, ed., Monopoly and Exploitation. Taipei: Taiwan Research Foundation.

Fujitani, T., trans. 1994. Tennō Pageant: Toward a Historical Ethnography of Modern Japan, by Yoneyama Lisa. Tokyo: NHK.

Haruyama Meitetsu. 1980. “Modern Japanese Colonial Rule and Hara Takashi.” In Haruyama Meitetsu and Wakabayashi Mashahiro, eds., The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, 1895–1934: Its Ruling Institutions and the Taiwanese National Movement. Tokyo: Japan Association for Asian Studies.

Haruyama Meitetsu and Wakabayashi Mashahiro. 1980. The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, 1895–1934: Its Ruling Institutions and the Taiwanese National Movement. Tokyo: Japan Association for Asian Studies.

Hsu Hsueh-chi. 1992. “The Lin of Banqiao in the Japanese Colonial Period—A Study of Family History and Its Political Relation.” In Family Process and Political Process in Modern Chinese History 2. Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica.

Huang Fu-san. 1995. “A Study on the Characters and Fates of Two Taiwanese Big Families: The Lin of Panchiau and the Lin of Wufong.” Paper presented at the one hundredth seminar on Taiwan Studies, Lin Benyuan Chinese Cultural Foundation.

Ka Chi-ming. 1983. “Colonial Economics.” Special forum on the review and prospect of the studies of the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan history: Newsletter of Taiwan History Field Research 26.

Lin Man-hung. 1988. “Trade and Social Economic Changes in the Late Qing Taiwan (1860–1895).” In Chang Yen-hsien, ed., History, Culture, and Taiwan—Fifty Seminars on Taiwan Studies. Banqiao: Taiwan Folkway Magazine Society.

Mitani Taiichirō. 1993. “Wartime System and Postwar System.” In Iwanami Seminar Modern Japan and Colony 8: Cold War in Asia and the Decolonization. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Taki Kōji. 1988. The Emperor’s Portrait. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

Wakabayashi Masahiro. 1980. “Taishō Democracy and the Petition for the Establishment of a Taiwan Parliament.” In Haruyama Meitetsu and Wakabayashi Mashahiro, eds., The Political Development of Japanese Colonialism, 1895–1934: Its Ruling Institutions and the Taiwanese National Movement. Tokyo: Japan Association for Asian Studies.

———. 1983a. “Taisho Democracy and the Petition for the Establishment of a Taiwan Parliament: Japanese Colonial Politics and the Taiwanese Anti-colonial Movement.” In A Historical Study of the Taiwanese Anti-colonial Movement. Tokyo: Kenbun Shupan.

———. 1983b. “The Colonial State and Taiwanese Native Landed Bourgeoisie: Questions Surrounding the Establishment of the Taichung Middle School, 1912–1915.” Ajia Kenkyu 29.4.

———. 1983c. “The Meaning of Mr. Huang Cheng-chung’s ‘Waiting the Opportunity.’” In A Historical Study of the Taiwanese Anti-Colonial Movement. Tokyo: Kenbun Shupan.

———. 1984. “The Situational Context of the Crown Prince’s Visit to Taiwan in 1923.” Kyoyo Gakka Kiyo 16:21–32.

———. 1992a. “The Crown Prince’s Taiwan Visit of 1923 and the ‘Principle of Extension of Mainland Law (Naichigenchoshugi).” In Iwanami Seminar Modern Japan and Colony 2: Structure of Imperial Rule. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.

———. 1992b. Taiwan: Democratization in a Divided Country. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Wu Micha. 1993. “Colonial Policy.” Special forum on the review and prospect of the studies of the Japanese colonial period in Taiwan history: Newsletter of Taiwan History Field Research 26.

———. 1994. “The Acceptance and the Task of the Study of Taiwanese History.” In Mizoguchi Yuzo, Hamashita Takeshi, Hiraishi Naoaki, and Miyajima Hiroshi, eds., Series Asian Perspectives 3: The Periphery in Asian Studies. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

———. 1995. “Afterword.” In Taiwan Research Foundation, ed., One Hundred Years of Taiwan. Taipei: Qianwei.

Wu Wen-hsing. 1992. A Study of Taiwanese Social Leadership Under Japanese Rule. Taipei: Zhengzhong.

Yanaihara Tadao. 1988 (1928). Taiwan Under Imperialism. Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten.