The modern professional humanist is an academic

person who pretends to despise measurement because of

its “scientific” nature. He regards his mandate as the

explanation of human expressions in the language of

normal discourse. Yet to explain something and to

measure it are similar operations. Both are translations.

George Kubler, 19621

There is no single direct and obvious way to measure the quality of an artist’s work over the course of his career. Instead, there is a variety of indirect ways. Each is based on a different kind of evidence, and each of these types of evidence was produced by a different group of judges. None of these groups of people were engaged in the activity that is my concern, of measuring individual artists’ creative life cycles. Yet as will be seen, each of the groups’ actions has the effect of generating evidence that can be used for just this purpose. The independence of the processes that generated the bodies of evidence means that comparison of the various results can serve to test the robustness of any conclusions. If the results obtained from the different measures agree, the degree of confidence in the collective results will obviously be greater than that associated with the results obtained from any single measure.

Each stylistic portion of an artist’s total time span constitutes

a separate sum of artifacts, and this is recognized

by the art market in the values it places upon certain

“periods” of an artist’s work in contrast to others.

Harold Rosenberg, 19832

Each year, the outcomes of auctions of fine art held throughout the world are collected by a publisher in Lausanne, Switzerland, and issued in bulky volumes titled Le Guide Mayer. These volumes provide the evidence for my econometric analysis of the prices of paintings. My analysis is based on the proposition that variation in the sale prices of a particular painter’s work, in all auctions held during the years 1970–97, can be systematically accounted for in part by the values of a set of associated variables for which evidence is given in Le Guide Mayer: specifically, these are the artist’s age when a given work was executed, the work’s support (paper or canvas), its size, and the date of its sale at auction.

The estimates obtained for the multiple regression equation for a given artist allow us to isolate the effect of an artist’s age at the time a painting was produced on the sale price of the painting, separating this effect from the impact on that price of the work’s support, size, and sale date. The estimates can therefore be used to trace out the relationship between age and price for an artist as illustrated in figures 2.1 and 2.2, which show the estimated age-price profiles for Cézanne and Picasso, respectively. Each of these figures represents the hypothetical auction values of a series of paintings of identical size, support, and sale date, done throughout the artist’s career.3

The auction market clearly values Cézanne’s late work most highly. Figure 2.1 shows that the estimated peak of his age-price profile is at age 67; a painting done in that year is worth approximately 15 times that of a work the same size he painted at age 26. In contrast, Picasso’s age-price profile reaches a peak at age 26—in 1907, the year he painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. A painting he did in that year would be worth more than four times as much as one the same size he produced when he was 67.

Before proceeding to consider other measures and other artists, it is useful to consider the impact of a potential bias involved in using auction data to estimate the relative value of an artist’s work over the life cycle. The issue in question involves famous artists, like Cézanne and Picasso, whose work is eagerly sought by museums. Although museums sometimes sell paintings, in general they are believed to be less likely to sell than are private collectors. How does the absence from the auction market of museum holdings of great artists’ work bias estimates like those of figures 2.1 and 2.2?

This question has never been systematically examined, but evidence for Cézanne can be drawn from John Rewald’s catalogue raisonné of his work, which includes information on the ownership of each painting at the time the book was published in 1996. Considering the oil paintings, the probability that a painting was owned by a museum was considerably greater for late than for early paintings.4 This in itself does not bias the age-price profile of figure 2.1, but would merely tend to reduce the amount of auction evidence on the value of late paintings from which to estimate that relationship. Yet what can bias the profile of figure 2.1 is that museums do not tend to take paintings randomly from a given period of an artist’s career, but rather pursue most avidly the best works. We do not have direct measures of quality for Cézanne’s paintings, but the catalogue raisonné does contain evidence on their sizes. This serves as a proxy for quality, for larger paintings are typically considered more important than smaller ones.5 Analysis of the evidence of the catalogue raisonné strongly confirms that the works by Cézanne owned by museums are on average considerably larger than those in private collections.6

Figure 2.1 Age-Price Profile for Paul Cézanne

Figure 2.2 Age-Price Profile for Pablo Picasso

The catalogue raisonné therefore shows that it is not just late works by Cézanne that are disproportionately removed from the auction market, but that it is the best of the late works that are most disproportionately absent. If none of Cézanne’s works were owned by museums, the average quality of his late paintings coming to auction would likely rise relative to the average quality of the early works sold, and the profile of figure 2.1 would consequently rise even more steeply with the artist’s age than it does. Thus for Cézanne the impact of museum purchases is actually to reduce the estimated value of the works from the period the auction market considers his best—the late works—relative to the rest of his paintings. This reinforces the conclusion from figure 2.1 that his latest works are the most valuable.7

Quality in art can be neither ascertained nor proved

by logic or discourse. Experience alone rules in this

area. . . . Yet, quality in art is not just a matter of

private experience. There is a consensus of taste. The

best taste is that of the people who, in each generation,

spend the most time and trouble on art, and this

best taste has always turned out to be unanimous,

within certain limits. Clement Greenberg, 19618

Few art historians or critics have been important art collectors, so although the judgments of art historians may play an important indirect role in determining the prices of paintings, through their influence on collectors, the art market does not directly measure the opinions of art scholars. This is not true, however, of textbooks, in which art scholars systematically set down their views.

Published surveys of art history nearly always contain photographs that reproduce the work of leading artists. These reproductions are chosen to illustrate each artist’s most important contribution or contributions. No single book can be considered definitive, because no single scholar’s judgments can be assumed to be superior to those of his peers, but pooling the evidence of the many available books can effectively provide a survey of art scholars’ opinions on what constitutes a given artist’s best period. The scores of authors and editors of textbooks of art history published in recent decades include many distinguished academics, among them George Heard Hamilton of Yale and Martin Kemp of Oxford, and such prominent critics as Robert Hughes of Time and John Canaday of the New York Times. But although the eminence of the authors varies, all the authors are likely to be among those who, in Clement Greenberg’s words, “spend the most time and trouble on art,” for they have made the considerable effort to communicate their views on the history of art in a systematic way. And for the modern period, the number of textbooks available is sufficiently large that no important result will be significantly influenced by the opinions of any single author or any one book.

Tabulating illustrations in textbooks is obviously analogous to a citation study, in which the relative importance of scholarly publications is judged by the number of citations they receive. Yet using illustrations as the unit of analysis has considerable advantages over citation counts, for illustrations are substantially more costly than written references. In addition to the greater space taken up by the illustration and the greater cost of printing, authors must obtain and pay for copyright permission to reproduce each painting, and must buy or rent a suitable photograph. This substantial cost in time and money implies that authors will be more selective in their use of illustrations, and that these may consequently give a more accurate indication than written references of what an author considers genuinely important.

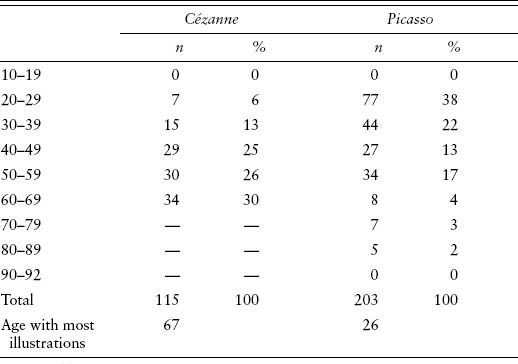

TABLE 2.1

Illustrations by Age, Cézanne and Picasso, from Books Published in English

Source: Tabulated from books listed in Galenson, “Quantifying Artistic Success,” 17n1.

Table 2.1 demonstrates the use of this evidence for Cézanne and Picasso. It presents the distribution of all the illustrations of their work, tabulated by the artist’s age at the date of the work’s execution, contained in 33 textbooks published in English since 1968. The contrast in the two distributions is striking. Whereas Cézanne’s illustrations rise steadily with age, with more than a third of his total representing works done in just the last eight years of his life, nearly two-fifths of Picasso’s illustrations are of works he painted in his 20s, with a sharp drop thereafter. And for both artists the single year represented by the largest number of illustrations is precisely the same as the year estimated to be that of the artist’s peak in value—age 67 for Cézanne, and 26 for Picasso.

Table 2.2 presents the comparable evidence for the same artists obtained from a survey of 31 textbooks published in French since 1963. The results are almost identical to those of table 2.1. French scholars clearly agree that Cézanne’s final decade was his greatest, and that Picasso was at his peak during his 20s. They equally consider Cézanne’s best single year to have been at age 67, and Picasso’s 26.

TABLE 2.2

Illustrations by Age, Cézanne and Picasso, from Books Published in French

Source: Tabulated from books listed in Galenson, “Measuring Masters and Masterpieces,” pp. 83–85, appendix.

I have never had either a first or a second or a third or

a fourth manner; I have always done what I wanted

to do, standing loftily apart from the gossip and

legends created about me by envious and interested

people. . . . If you think of all my exhibitions from

1918 until today you will see continual progress,

a regular and persistent march towards those summits

of mastery which were achieved by a few consummate

artists of the past.

Giorgio de Chirico, 19629

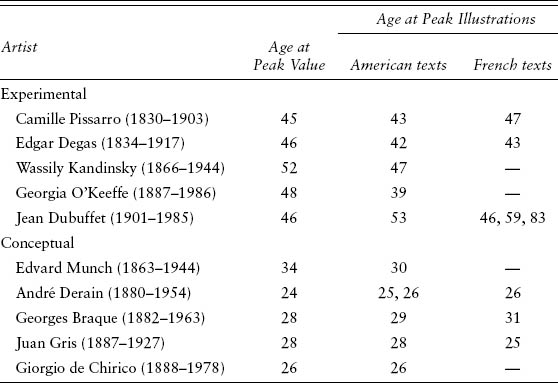

TABLE 2.3

Peak Ages, Ten Early Modern Artists

Sources: Age at peak value: Galenson, Painting outside the Lines, tables 2.1, 2.2. For artists who do not appear in those tables, prices were estimated as described there.

Age at peak illustrations: Galenson, “Quantifying Artistic Success,” table 5; Galenson, “Measuring Masters and Masterpieces,” table 5; Galenson, “The New York School vs. the School of Paris: p. 146; Galenson, “Toward Abstraction”; Galenson, “Before Abstract Expressionism.”

Note: The entry given is the artist’s age in the single year from which the textbooks reproduce the largest number of the artist’s paintings.

The use of the two measures of artists’ life cycles just described can be illustrated more generally with some additional examples. Evidence for the two measures for ten important modern painters is given in table 2.3.

The evidence of both prices and illustrations places Camille Pissarro’s best period in his mid-40s. Pissarro was one of the core group of landscape painters—together with Monet, Renoir, and Sisley—who pioneered the development of Impressionism. The greatest achievements of this group are widely recognized as having come in the 1870s, when Pissarro was in his mid-40s. During that decade the impact of the group’s discoveries was so great that nearly all of Paris’s advanced artists, including painters as disparate as Manet, Cézanne, Gauguin, and van Gogh, were lured into experiments with their methods. Impressionism was quintessentially a visual innovation, aimed at capturing “fugitive impressions of nature,” and both Pissarro’s goals and his methods identify him as experimental.10 His art was visual, and he needed attractive views. Looking for a new home in 1883, he complained of the ugliness of one town: “Can a painter live here? I should have constantly to go off on trips. Imagine! No! I require a spot that has beauty!”11 Pissarro struggled with finishing his paintings, as, for example, in 1895 he wrote to his son that he had nearly completed a series of large paintings but confessed, “I am letting them lie around the studio until I find, at some moment, the final sensation that will give life to the whole. Alas! while I have not found this last moment I can’t do anything further with them.”12

Both types of evidence in table 2.3 similarly place Edgar Degas’s best period in his mid-40s. Degas often expressed his belief in repetition, saying, “One must redo ten times, a hundred times the same subject,” because of his perennial dissatisfaction with his achievements.13 His dealer Ambroise Vollard observed that “the public accused him of repeating himself. But his passion for perfection was responsible for his continual research.”14 A friend, the poet Paul Valéry, wrote, “I am convinced that [Degas] felt a work could never be called finished, and that he could not conceive how an artist could look at one of his pictures after a time and not feel the need to retouch it.”15 Degas’s studies of ballet dancers are an example of a large body of work in which his experimental innovations in the representation of space emerged gradually, so although the series is famous as a whole, it lacks any one or two particularly famous landmark works. As Degas’s friend, the critic George Moore, observed, “He has done so many dancers and so often repeated himself that it is difficult to specify any particular one.”16

The quantitative measures of table 2.3 place Wassily Kandinsky’s best work around the age of 50, during the late 1910s, when he was pioneering an abstract art. In spite of Kandinsky’s writings on metaphysics, the inspiration for his art was visual, and his development of it experimental. He himself described the visual origins of his recognition of the potentialities of nonrepresentational painting, recalling an evening in 1910 when he returned to his studio around dusk and was startled to see “an indescribably beautiful picture, pervaded by an inner glow.” On approaching the mysterious painting he discovered that it was one he had done earlier, standing on its side. This experience prompted him to set out on a search for forms that could be expressive even though unrelated to real objects. As he emphasized, however, he did not achieve this goal quickly, for “only after many years of patient toil and strenuous thought, numerous painstaking attempts, and my constantly developing ability to conceive of pictorial forms in purely abstract terms, engrossing myself more and more in these measureless depths, did I arrive at the pictorial forms I use today, on which I am working today and which, as I hope and desire, will themselves develop much further.”17 In considering the three great pioneers of abstract art, John Golding contrasted the progression of the experimental artists Kandinsky and Mondrian with that of the conceptual Malevich: “It might be fair to say that Malevich’s abstraction sprang, Athena-like, ready formed from the brow of its creator; this distinguishes Malevich’s approach very sharply from that of both Mondrian and Kandinsky, who had sensed and inched their way into abstraction over a period of many years.”18

The difference of nine years between the two measures of Georgia O’Keeffe’s best work in table 2.3, while not extreme, is indicative of the absence of specific breakthrough years that resulted from her experimental approach. From the beginning of her career O’Keeffe often painted particular subjects in series. She explained, “I work on an idea for a long time. It’s like getting acquainted with a person, and I don’t get acquainted easily.”19 The series generally involved a progression: “Sometimes I start in very realistic fashion, and as I go from one painting to another of the same thing, it becomes simplified till it can be nothing but abstract.”20 But her persistence was nonetheless a product of dissatisfaction. Over a period of 15 years, she painted a door of her house in New Mexico more than 20 times. She explained, “I never quite get it. It’s a curse—the way I feel I must continually go on with that door.”21 Her experimental attitude toward art led her to distrust the idea of the individual masterpiece: “Success doesn’t come with painting one picture. It results from taking a certain definite line of action and staying with it.” Not surprisingly, this led her to believe that artists must mature slowly: “Great artists don’t just happen. . . . They have to be trained, and in the hard school of experience.”22

The quantitative measures of table 2.3 for Jean Dubuffet agree only that he did his best work after the age of 45. Dubuffet’s art was visual, as his goal was to draw on a variety of types of art by the self-taught or untrained to break with traditional concepts of artistic beauty and create an art that represented the viewpoint of the common man. He devoted considerable effort to devising new technical procedures to achieve this, including the use of accidental effects. During the 1950s, for example, he produced works he called assemblages by cutting up and reassembling painted surfaces. He explained that this technique, “so rich in unexpected effects, and with the possibilities it offers . . . of making numerous experiments, seemed to me an incomparable laboratory and an efficacious means of invention.”23 Describing him in the late 1950s, a critic observed that “the level of [Dubuffet’s] work to date was uncommonly even,” and this assessment can clearly be extended much further. There are no individual celebrated master works or pronounced peaks in Dubuffet’s remarkably long career, but instead an outpouring of a large body of work that evolved over time but that was nonetheless unified by a distinctive philosophy and approach.24

Turning to the conceptual artists in table 2.3 shifts our attention to a different type of career, in which artists’ major contributions appear precipitously, and generally at an earlier age. The quantitative measures for Edvard Munch both point to a peak period early in his 30s, during which he was systematically using insights he had gained from the work of Gauguin and other Symbolists during a recent trip to Paris, to express his own states of mind. Munch’s most famous single work, and one of the most celebrated paintings of the late nineteenth century, was developed from a series of sketchbook drawings, and then was worked out in pastel, before being painted in oils. That painting, The Scream, uses distortions of perspective and of shapes to create a visual image of extreme anxiety. As Munch recorded the experience that inspired the painting, it occurred as he walked one day at sunset: “Suddenly the sky became a bloody red. . . . I stood there, trembling with fright. And I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature.”25 Both Munch’s goal of expressing emotions and his routine use of preparatory studies mark him clearly as a conceptual innovator. Although he lived past the age of 80, he never again produced work as powerful, or influential, as that of his youth.

The auction market and the textbooks, both English and French, agree that André Derain produced his most important work in his mid-20s. This was done during a short span of time, 1904–6, when Derain joined Matisse, Vlaminck, and several other young artists in the invention and practice of Fauvism. The movement extended Symbolism, which had developed during the late nineteenth century, to a logical extreme through the use of bright, exaggerated color, flattened images, and visible brushwork. Recognizing the conceptual basis of the art, Derain later admitted, “We painted with theories, ideas.”26 Fauvism was among the most short-lived of major movements in modern art, as Derain and his friends largely abandoned it within little more than three years. Derain thereafter began to work in a derivative Cubist style before painting for many decades in a more conservative manner that led him to be “displaced from the center of the progressive effort.” Historian George Heard Hamilton concludes that “the tragedy of André Derain, if such it was, lay in the discrepancy between his early promise and his later ambitions”; this may be an epitaph not only for Derain, but for a number of conceptual innovators who have become prominent by making a dramatic early contribution but have been unable to follow it with comparable later innovations.27

Georges Braque was a minor member of the Fauve movement, but the measures of table 2.3 show that his greatest work came a few years later, when he was in his late 20s. This was of course when he joined Picasso in developing Cubism, as from 1909 until Braque joined the French army in 1914 the two worked together “like two mountaineers roped together.”28 As noted earlier, Cubism was a conceptual innovation in which the artists expressed their full knowledge of objects, without being bound by the constraint of painting what they could see of an object from a single location. Thus Braque ridiculed the single viewpoint of Renaissance perspective, saying, “It is as if someone spent his life drawing profiles and believed that man was one-eyed.”29 Although he was wounded in World War I, Braque painted for many years afterward, but he never again worked with Picasso. His later work is more highly regarded than that of Derain, but it produced no further major innovations, as up to the age of 80 and beyond Braque continued to work within a Cubist style that he had largely worked out by the age of 30.

Picasso admitted one other young painter, Juan Gris, into his and Braque’s inner circle of Cubism in 1911. Gris contributed to the development of the later, Synthetic phase of Cubism, and all the evidence of table 2.3 places his best work during his late 20s, in the short span of time just after he began working with Picasso and Braque. The critic Guillaume Apollinaire called Gris a “demon of logic” for his effort to make Cubism a more systematic and rigorous form. Instead of beginning with fragments of objects and building compositions, like Picasso and Braque, in Gris’s “deductive method” abstract compositions were plotted out in advance, with shapes and positions often calculated mathematically or constructed with a compass, and objects were then fitted into this framework.30 Historian Christopher Green observed that Gris’s planning for his paintings was followed by “an immaculacy of oil technique that masked utterly the trace of process,” while John Golding described Gris’s papier collés as having a look of “tailor-made precision,” equally a consequence of Gris’s meticulous preparation.31 Gris’s goals also revealed his conceptual attitude, as in 1919 he wrote to his dealer and friend Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, “I hope to be able to express an imagined reality with great precision using the pure elements of the mind.”32 Although Gris died prematurely, at the age of just 40, his most innovative work was already more than a decade in the past.

Giorgio de Chirico arrived in Paris in 1911, at the age of 23, and during the next six years produced a series of strikingly original paintings in which he sought to present imagined scenes that would give art the clarity “of the dream and of the child mind.” He called these works metaphysical, and the poet André Breton, the founder and leader of the Surrealist movement, considered them the most important twentieth-century inspiration for Surrealist painting.33 After serving in the Italian army in World War I, de Chirico remained in Italy and changed his style dramatically under the influence of his study of the work of a number of old masters. Historian James Thrall Soby observed that de Chirico’s adoption of a neoclassical, academic style led abruptly to his “collapse . . . as an original, creative artist.”34 The change also led to a falling-out with the Surrealists. Breton continued to praise de Chirico’s early work but denounced the paintings he did after World War I. The Surrealists tried to induce de Chirico to return to his earlier style, but he resisted; Soby argues that his inspiration had disappeared, as “the hallucinatory intensity of his early art was spent.”35 De Chirico’s curious reaction against the Surrealists’ continued attacks on him led him not only vehemently to denounce modern art, but to produce numerous exact copies of the great early paintings that had established his reputation. By falsely dating these copies, de Chirico became a forger of his own early work. Whether motivated by spite or financial gain, de Chirico was never able to convince the art world of the superiority of his late over his early work. Although he continued to paint until his death at 90, as the measures of table 2.3 suggest, de Chirico’s reputation rests almost entirely on the paintings he produced in his mid-20s, which influenced almost every important Surrealist painter.

This brief examination of the careers of ten important modern artists serves to illustrate the value of measuring systematically, and in several ways, the timing of artists’ major contributions. Although many more artists could be considered, these cases demonstrate that the auction market and textbook treatments tend to agree quite closely on when painters produced their best work. Table 2.3 also shows how sharply the careers of experimental artists can differ from those of conceptual innovators, as for the artists included all the measures indicate that the experimental painters produced their best work beyond the age of 40, whereas the conceptual artists had generally reached their peaks by the age of 30.

“Jasper Johns: A Retrospective” is the most significant

survey of this artist’s work ever organized, a full and

clear mapping of his four decades of exploration, traced

in paintings, drawings, prints, and sculptures.

Geoffrey C. Bible, 199636

Unlike textbook illustrations, which are most often chosen to represent the author’s judgment of an artist’s most important work, systematic critical evaluations of the relative quality of artists’ work over the course of their entire careers are implicit in the composition of retrospective exhibitions. Museum curators who organize retrospective exhibitions tacitly reveal their judgments of the importance of an artist’s work at different ages through their decisions on how many paintings to include from each phase of the artist’s career. The distribution by age at execution of an artist’s works that are included in these exhibitions can consequently serve as a third quantitative measure of the quality of work over the course of artists’ careers.

TABLE 2.4

Distribution by Artist’s Age of Paintings Included in Retrospective Exhibitions, Cézanne and Picasso

Source: Cachin, Cahn, Feilchenfeldt, Loyrette, and Rishel, Cézanne ; Rubin, Pablo Picasso.

Retrospectives are often organized by a single curator, and it might consequently be objected that their composition is an unreliable guide to an artist’s career because it is subject to idiosyncratic preferences or simply ignorance. Yet organizers of major retrospectives normally work with many other art historians, both within and outside their own institutions. The composition of a retrospective therefore typically represents the collective judgment of a group of scholars. In general, it also appears that the larger the museum arranging the retrospective, the greater the number of scholars who work to assemble and analyze it. Retrospectives presented by major museums may consequently be least subject to this criticism. Important artists are usually given retrospectives by wealthy museums, so for the painters considered here retrospectives can generally be assumed to represent careful and considered reviews of their careers.

Table 2.4 presents the age distributions of the works included in the most recent full retrospective exhibitions for Cézanne and Picasso. These closely resemble the age distributions of textbook illustrations of the two artists’ work shown in tables 2.1 and 2.2. For both artists the retrospectives’ age distributions are slightly less skewed toward the peak ages; this is to be expected, since one obvious purpose of these exhibitions is to illustrate the artist’s work at all stages of his career. But it is nonetheless clear that the Cézanne respective gave its greatest emphasis to his final decades, and that the Picasso exhibition gave the greatest weight to his early years. The single years most heavily represented in the retrospectives—age 67 for Cézanne, and age 26 for Picasso—were precisely the same as the estimated ages at peak value for both artists, and were therefore also the same ages most heavily represented in both the American and French textbooks.

Retrospectives may less often be useful for earlier modern artists than for more recent artists. The paintings of earlier great modern artists, like Cézanne and Picasso, have become so valuable, and are in many cases so important in attracting visitors to museums’ permanent collections, that full retrospective exhibitions of their work are rarely held. Thus although parts of these artists’ careers are frequently featured in special exhibitions, comprehensive retrospectives are rarely mounted. The Cézanne exhibition used for table 2.4 was held in 1996, but it was the first full survey of his work since 1936, and the Picasso retrospective used for table 2.4 was held more than 20 years ago, in 1980. This is less true, however, for important artists of the more recent past. Thus, for example, just within the past 10 years comprehensive retrospectives have been held for such important artists of the post–World War II era as Jasper Johns, Willem de Kooning, Roy Lichtenstein, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, and Mark Rothko. Retrospective exhibitions can consequently be a particularly valuable source for studying the careers of recent modern artists.

We believe that we can find the end, and that a painting

can be finished. The Abstract Expressionists always felt

the painting’s being finished was very problematical.

We’d more readily say that our paintings were finished

and say, well, it’s either a failure or it’s not, instead of

saying, well, maybe it’s not really finished.

Frank Stella, 196637

The effect of adding the evidence of retrospective exhibitions to the two measures used earlier can be demonstrated by considering the careers of ten prominent members of the two generations of American painters who dominated modern art after World War II. The first of these generations was dominated by experimental innovators, and the second by conceptual innovators.

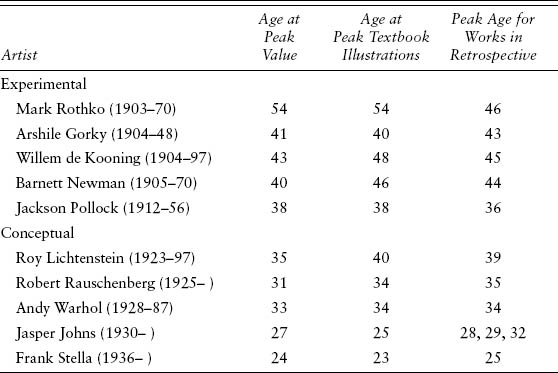

TABLE 2.5

Peak Ages, Ten American Painters

Sources: Age at peak value: Galenson, Painting outside the Lines, table 2.2.

Age at peak textbook illustrations: Galenson, “Was Jackson Pollock the Greatest Modern American Painter?” table 5.

Age at peak number of works in retrospective: tabulated from retrospective catalogues listed in Galenson, Painting outside the Lines, table B.1.

The first five artists listed in table 2.5 are the leading members of the Abstract Expressionists. This was a group united not by a style, but by a desire to draw on the subconscious to create images, and all the members of the group used an experimental approach. The absence of preconceived outcomes was a celebrated feature of Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock’s signature drip method of applying paint, with the inevitable puddling and spattering that could not be completely controlled by the artist, became the trademark symbol of this lack of preconception, reinforced by his statement, “When I am in my painting, I’m not aware of what I’m doing.”38 Mark Rothko wrote that his paintings surprised him: “Ideas and plans that existed in the mind at the start were simply the doorway through which one left the world in which they occur.”39 Barnett Newman expressed the same idea less dramatically: “I am an intuitive painter. . . . I have never worked from sketches, never planned a painting, never ‘thought out’ a painting before.”40 Arshile Gorky’s widow recalled that he “did not always know what he intended and was as surprised as a stranger at what the drawing became. . . . It seemed to suggest itself to him constantly.”41 Willem de Kooning told a critic, “I find sometimes a terrific picture . . . but I couldn’t set out to do that, you know.”42

The Abstract Expressionists developed their art by a process of trial and error. In 1945 Rothko wrote to Newman that his recent work had been exhilarating but difficult: “Unfortunately one can’t think these things out with finality, but must endure a series of stumblings toward a clearer issue.”43 This description applied equally to the production of individual paintings. Elaine de Kooning recalled that her husband repeatedly painted over his canvases: “So many absolutely terrific paintings simply vanished because he changed them and painted them away.”44 Newman declared, “My work is something that has happened to me as much as something that has happened to the surface of the canvas.”45 An assistant who worked for Rothko in the 1950s remembered how he “would sit and look for long periods, sometimes for hours, sometimes for days, considering the next color, considering expanding an area”; a biographer observed that the extent of these periods of study was such that “since the late 1940s Rothko, building up his canvases with thin glazes of quickly applied paint, had spent more time considering his evolving works than he had in the physical act of producing them.”46 Like the other Abstract Expressionists, Rothko believed that progress came slowly, in small increments. He made his trademark image of stacked rectangles the basis for hundreds of paintings over the course of two decades, declaring, “If a thing is worth doing once, it is worth doing over and over again—exploring it, probing it.”47

The Abstract Expressionists wanted to create new visual representations of their emotions and states of mind. Rothko declared his aim of “finding a pictorial equivalent for man’s new knowledge and consciousness of his more complex inner self.”48 Pollock told an interviewer, “The unconscious is a very important side of modern art. . . . The modern artist, it seems to me, is working and expressing an inner world.”49 Their aspirations for what their work might accomplish were considerable. Newman believed that his work’s rejection of aesthetic systems made it an “assertion of freedom”; when a critic challenged him to explain what one of his paintings could mean to the world, he replied that “if he and others could read it properly it would mean the end of all state capitalism and totalitarianism.”50

With enormously ambitious but extremely vague goals, the Abstract Expressionists were continually uncertain not only whether their paintings were successful, but even whether individual works were finished. Newman declared simply, “I think the idea of a ‘finished’ picture is a fiction.”51 De Kooning recalled that he considered his series of paintings of Women—now generally considered his most important achievement—a failure, but that had not fazed him: “In the end I failed. But that didn’t bother me. . . . I didn’t work on it with the idea of perfection, but to see how far one could go—but not with the idea of really doing it.”52 Pollock’s widow, Lee Krasner, recalled that during the early 1950s, even after he had been recognized as a leader of the Abstract Expressionists, one day “in front of a very good painting . . . he asked me, ‘Is this a painting?’ Not is this a good painting, or a bad one, but a painting ! The degree of doubt was unbelievable at times.”53

The Abstract Expressionists came to dominate American art during the 1950s, and many younger artists directly followed their methods and goals. Yet some aspiring artists found the art and attitudes of the Abstract Expressionists oppressive. Reacting against what they considered the excessive and pretentious emotional and philosophical claims of Abstract Expressionism, these younger artists created a variety of new forms of art. Although these new approaches did not belong to any single movement or style, they shared a desire to replace the complexity of Abstract Expressionist gestures and symbols with simpler images and ideas. In the process, during the late 1950s and the ’60s, they succeeded in replacing the experimental methods of the Abstract Expressionists with a conceptual approach.

These younger artists planned their work carefully in advance. Frank Stella explained that “the painting never changes once I’ve started to work on it. I work things out beforehand in the sketches.”54 Roy Lichtenstein prepared for his paintings by making drawings from original cartoons, then projecting the drawings onto canvas and tracing these projected images to create the outlines for the figures in his paintings. Although Lichtenstein’s cartoon paintings were very different from Stella’s geometric patterns, in 1969 Lichtenstein specifically compared the central concern of his work to Stella’s: “I think that is what’s interesting people these days: that before you start painting the painting, you know exactly what it’s going to look like.”55 Andy Warhol’s goal was to make his images so clear and simple that he did not have to participate in executing his paintings: “I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me.”56

All these artists wanted the images in their work to be clear and straightforward. Stella emphasized that “all I want anyone to get out of my paintings . . . is the fact that you can see the whole idea without any confusion.”57 Jasper Johns explained that he chose to paint flags, targets, maps, and numerals because “they seemed to me preformed, conventional, depersonalized, factual, exterior elements.”58 Some of the artists produced their paintings, or had them produced, mechanically. Warhol used silk screens manufactured by commercial printers from photographs he selected from magazines or newspapers because “hand painting would take much too long and anyway that’s not the age we’re living in. Mechanical means are today.”59 Lichtenstein mimicked mechanical production: “I want my painting to look as if it had been programmed. I want to hide the record of my hand.” He stressed the contrast with his predecessors: “Abstract Expressionism was very human looking. My work is the opposite.”60

These younger artists emphatically rejected the emotional and psychological symbolism that the Abstract Expressionists had considered central to their art. Stella told an interviewer: “I always get into arguments with people who want to retain the old values in painting—the humanistic values they always find on the canvas. If you pin them down, they always end up asserting that there is something there besides the paint on the canvas. My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there.”61 Similarly, when asked if he was antiexperimental, Lichtenstein replied, “I think so, and anti-contemplative, anti-nuance, anti-movement-and-light, anti-mystery, anti-paint-quality, anti-Zen, and anti all those brilliant ideas of preceding movements which everyone understands so thoroughly.”62

A generation dominated by experimental artists was thus followed by one dominated by conceptual artists. Many implications of this shift have been discussed by art critics and historians, yet art scholars have not given systematic attention to the consequences of the shift for artists’ life cycles. The three measures introduced earlier are presented in table 2.5 for the leading members of each of the two generations.63

A comparison of the three measures shows that they agree quite closely on when each individual artist produced his best work. The age at which an artist did his work of peak auction value never differs by more than eight years from either the age of most textbook illustrations or the age most heavily represented in the artist’s retrospective exhibition, and for eight of the ten artists this difference is five years or less.

Table 2.5 also shows that the generational shift from experimental to conceptual innovators was accompanied by a sharp drop in the ages at which artists produced their best work. All three measures agree that Pollock’s best period was in his late 30s, and that the other Abstract Expressionists’ peaks all came after the age of 40. In contrast, of the next generation the three measures place Lichtenstein’s peak in his late 30s, and those of the other four artists from their mid-20s to their early 30s. Thus the dramatic change in philosophy that occurred when Abstract Expressionism was replaced by Pop art was accompanied by a dramatic shift in the careers of the leading members of the two groups.

Artists of genius are few in number. . . . [T]he museum

collection aspires to show a chronological sequence of

the work of such artists, carrying forward an argument

which forms the material of any history of modern art.

Alan Bowness, 198964

The decisions of museums, even apart from their assembly of retrospective exhibitions, provide another source of information on artists’ major contributions. Museums wish to present the best work of the most important artists, and they consequently reveal their judgments of what this best work is in a number of ways. One is through their decisions on what to display. Most museums have the space to exhibit only a small fraction of all the paintings they own. Curators’ decisions regarding which paintings to display therefore indicate what they consider the most important among the works available to them. These selections are of course constrained by the contents of the museums’ collections. But the greatest museums, with the largest and best collections of the work of major artists, will be the least constrained in this way. The paintings these museums choose to hang will consequently tend to be good indications of their curators’ judgments about when artists produced their best work.

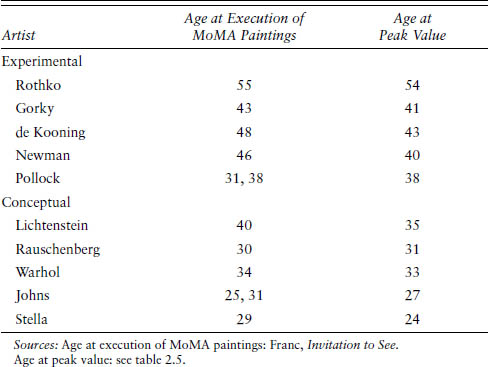

A related source of information on curators’ judgments is even more readily accessible. Nearly all major museums now publish illustrated books presenting their collections to the public. These books vary in size but often serve as highly selective surveys to what the museums judge to be their best works. An example of how these books can be used is afforded by An Invitation to See, the revised edition of which was published in 1992 by New York’s Museum of Modern Art, and which contains photographs and brief discussions of 150 works selected from the museum’s collection.65 For the same 20 artists included in tables 2.3 and 2.5, tables 2.6 and 2.7 present the ages of the artists when they executed those of their works included in Invitation to See.

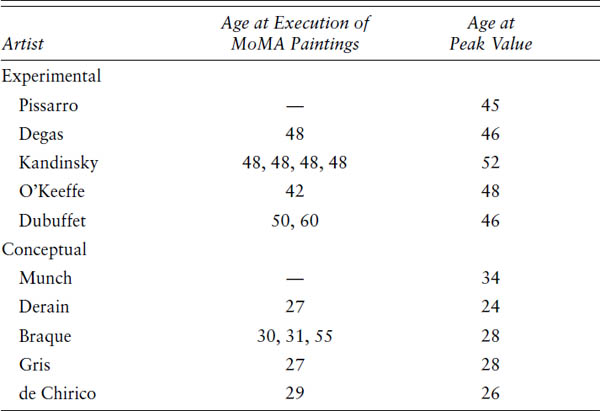

In table 2.6, the median age of Degas, Kandinsky, O’Keeffe, and Dubuffet—the four experimental artists from table 2.3 included in Invitation to See—when they executed the eight paintings reproduced in the book was 48 years, whereas the median age of the conceptual innovators Derain, Braque, Gris, and de Chirico when they produced the six of their paintings treated in the book was just 29.5 years. Table 2.7 shows that the six paintings of the Abstract Expressionists reproduced in Invitation to See were made by the artists at a median age of 44.5, whereas the six reproduced works by the five conceptual painters of the next generation were made at a median age of just 30.5. In addition, Invitation to See includes three paintings by Cézanne, executed at a median age of 59, and seven paintings by Picasso, done at a median age of 33. Analysis of the Museum of Modern Art’s own selection of works from its collection therefore demonstrates that the museum’s curators strongly agree that the experimental artists considered here produced their most important work considerably later in their careers than did the conceptual innovators.

TABLE 2.6

Ages at Which Artists Included in Table 2.3 Executed Paintings Reproduced in An Invitation to See

Sources: Age at execution of MoMA paintings: Franc, Invitation to See. Age at peak value: see table 2.3.

The Museum of Modern Art is known for the great strength of its collection of American paintings of the post–World War II era.66 In view of this, it is striking to note how closely the museum’s selection of works by the artists in table 2.7 agrees with the auction market. Of the 12 paintings illustrated in Invitation to See by these ten American artists, none was made more than seven years from the respective artist’s estimated age at peak value, 10 of the 12 were made within five years of that age, and fully half were made within just two years of the age at peak value.

Interestingly, in a very different context an official of the Museum of Modern Art recently explained precisely why the museum’s decisions about what to acquire and exhibit so closely track the key times in artists’ careers. When he was asked in 2003 why the museum has shown little interest in the recent work of Frank Stella, who is now in his 60s, John Elderfield, the museum’s chief curator of the Department of Painting and Sculpture, told a reporter for the New York Times, “The moment in Frank’s career which is of particular interest to MOMA is what happened in the 60’s, because that was the moment when he entered and transformed painting.” Elderfield then gave a general explanation that is clearly consistent with the position taken in this book: “MOMA is a museum interested in telling the story of successive innovations rather than a museum interested in the longevity of individual careers.”67

TABLE 2.7

Ages at Which Artists Included in Table 2.5 Executed Paintings Reproduced in An Invitation to See

This sounds like tall talk, but you can take nearly any

picture or sculpture in this exhibition and if it were

in another show with other works like it, it would

be considered one of the best.

Peter Marzio, director of the Houston Museum of

Fine Arts, on “The Heroic Century”68

An unusual opportunity to observe the judgments of art experts as to the most important works in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection was a product of the recent closing of the museum’s Manhattan building for renovations. With the museum temporarily relocated to much less spacious quarters in Queens, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts seized the opportunity to exhibit a selection from the Museum of Modern Art’s permanent collection that had been placed in storage. Titled “The Heroic Century,” the exhibition ran in Houston from September 2003 to January 2004. Given what a news account described as “nearly carte blanche access” to the permanent collection of the Museum of Modern Art, a Houston curator expressed his excitement: “A show like this . . . is once in a lifetime.” The director of the Houston museum declared the show to be the most important with which he had been involved in a career of more than 35 years. Interestingly, he added, “This may be the most expensive show ever organized in terms of value.”69

The selection of the paintings in the exhibition was done jointly by the staffs of the two museums. Thus the chief curator of the Museum of Modern Art emphasized that a “large percentage” of the 200 works presented in the show will be placed on permanent display when the museum returns to its Manhattan building.70

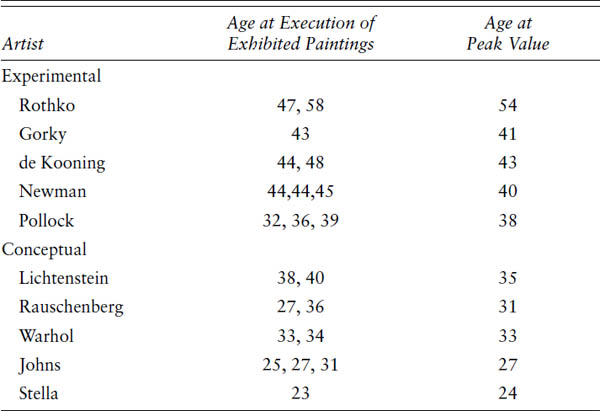

“The Heroic Century” included three paintings by Cézanne, executed at a median age of 60, and 11 paintings by Picasso, done at a median age of 32. The exhibition also included works by seven of the ten artists considered above in table 2.3, and by all ten of the artists listed in table 2.5. Tables 2.8 and 2.9 present the distributions of these paintings by the artists’ ages when they were made.

The median age at which the two experimental artists in table 2.8 made the paintings exhibited was 48, whereas the comparable median age for the five conceptual artists was just 26. In table 2.9, the median age at which the experimental artists made the paintings exhibited was 44, compared with 32 for the conceptual artists. None of the 16 paintings listed in table 2.8 was made more than six years from the respective artist’s estimated age at peak value, and none of the 21 works listed in table 2.9 was made more than seven years from the respective artist’s age at peak value.

“The Heroic Century” was justifiably described as “a ‘greatest hits’ compilation of modern art.”71 This careful selection of outstanding paintings from one of the world’s greatest collections of modern art clearly reveals the judgment of art experts that experimental painters produce their greatest work considerably later in their careers than their conceptual counterparts. It also demonstrates that their judgment in this matter is virtually the same as that of the collectors who buy modern art at auction.

TABLE 2.8

Ages at Which Artists Included in Table 2.3 Executed Paintings Exhibited in “The Heroic Century”

Sources: Age at execution of exhibited paintings: Elderfield, Visions of Modern Art. Age at peak value: see table 2.3.

There is, it seems, a graph of creativity which can

be plotted through an artist’s career.

Alan Bowness, 198972

Systematic measurement of the quality of artists’ work over the course of their careers is a recent development, so it is perhaps not surprising that art historians are not widely aware of how, and how well, it can be done. It is clear, however, that art historians had not anticipated that such measurements were possible, and unfortunately, it is also clear that many continued to deny the possibility of these measurements even after they had begun to appear. Thus for example as recently as 1998, a curator at New York’s Museum of Modern Art declared that an artist’s success “is completely unquantifiable.”73 This chapter’s survey of methods of measurement and its illustrations of their use demonstrate decisively that this curator was wrong, and that artistic success can be measured, not only with evidence drawn from the auction market and from textbooks of art history, but even from decisions made by curators, including those of his own museum. The consistency of the evidence from this remarkably wide range of sources on the hypothesis examined here constitutes powerful evidence not only that conceptual artists arrive at their major contributions at younger ages than their experimental counterparts, but also that, as Clement Greenberg asserted, there is a strong consensus among those in the art world on what is important in art.

TABLE 2.9

Ages at Which Artists Included in Table 2.5 Executed Paintings Exhibited in “The Heroic Century”

Sources: Age at execution of exhibited paintings: Elderfield, Visions of Modern Art. Age at peak value: see table 2.5.

The variety of methods by which artists’ careers can be quantified is valuable, as noted previously, for checking and reinforcing the validity of any single measurement. It is also valuable, however, for cases in which some sources of evidence are unavailable for an artist of interest. Marcel Duchamp produced very few works of art during his career, and only nine of his paintings came to auction during 1970–97, a number much too small to support meaningful statistical analysis. Yet Duchamp’s work plays an important role in the development of modern art, and consequently has been examined intensively by textbooks and museums. The timing of his principal innovation emerges clearly from these sources. The surveys of both the American and French textbooks described earlier identify 1912, when Duchamp was 25 years old, as the most important year of his career, represented by the most illustrations.74 An Invitation to See reproduces two works by Duchamp, executed in 1912 and 1918, when Duchamp was 25 and 31 years old, respectively. Since Duchamp lived past the age of 80, this concentration on his early work strongly suggests that his principal innovation was conceptual. The text of an Invitation to See immediately confirms this. The first sentence of the book’s discussion of The Passage from Virgin to Bride (1912) reads: “While still in his twenties, Duchamp determined to get away from the physical aspect of painting in order to create ideas rather than mere ‘visual products.’ ” To emphasize that Duchamp’s goal was a conceptual one conceived at an early age, the first sentence of the same book’s discussion of his To Be Looked at (From the Other Side of the Glass) with One Eye, Close To, for Almost an Hour (1918) again made this point: “While still in his twenties, Duchamp determined to get away from the physicality of painting and ‘put painting once again at the service of the mind’ by creating works that would appeal to the intellect rather than to the retina.”75 These sources thus leave little doubt that art scholars judge Duchamp to have been a conceptual young genius rather than an experimental old master.