The analysis of the two life cycles of creativity that has been presented in this book was initially developed by studying modern painters. The preceding chapter, however, showed that it can profitably be extended to the careers of premodern painters. Recent research has in fact established that the analysis can be applied much more broadly, to other intellectual activities. The value of doing this will be demonstrated in this chapter, through reference to selected important practitioners of four other arts. In each case, although the number of artists considered will not be large, the purpose is to illustrate how the analysis can be applied to important features of the methods and products of major figures in each activity, and can be used to gain a systematic understanding of the nature and timing of their major contributions.

The only principle in art is to copy what you see.

Auguste Rodin, 19061

An object to me is the product of a thought.

Robert Smithson, 19692

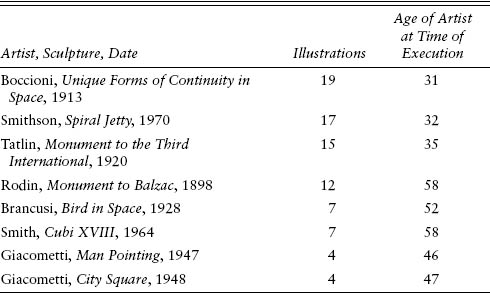

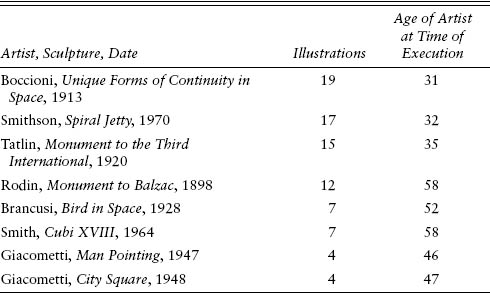

Tables 6.1 and 6.2 are based on a survey of all the illustrations of sculptures made by seven selected modern sculptors that are contained in 25 textbooks of art history. Table 6.1 ranks the seven sculptors by the total number of illustrations of their work that appear in all the books. Four sculptors (Auguste Rodin, Constantin Brancusi, Alberto Giacometti, and David Smith) all have well over 25 total illustrations, or more than one per book, whereas three (Umberto Boccioni, Vladimir Tatlin, and Robert Smithson) all have less than 1 illustration per book. The order of these two groups is reversed in table 6.2, however, when the seven sculptors are ranked according to the number of illustrations the same books contain of the single most often reproduced sculpture by each. Thus Boccioni, Smithson, and Tatlin each made one sculpture that is reproduced in well over half the books surveyed, whereas no single work by Rodin, Brancusi, Giacometti, or Smith appears in as many as half the books. Interestingly, also, the individual sculptures listed for Boccioni, Smithson, and Tatlin in table 6.2 clearly dominate their careers from the vantage point of the textbooks, as each accounts for more than three-quarters of the total illustrations of those sculptors’ works shown in table 6.1.

TABLE 6.1

Ranking of Selected Modern Sculptors by Total Illustrations in 25 Textbooks

Artist |

Illustrations |

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) |

65 |

Constantin Brancusi (1876–1957) |

51 |

Alberto Giacometti (1901–1966) |

39 |

David Smith (1906–1965) |

34 |

Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916) |

21 |

Vladimir Tatlin (1885–1953) |

19 |

Robert Smithson (1938–1973) |

19 |

Source: See table 4.6.

Taken together, tables 6.1 and 6.2 pose several interesting puzzles. First, why didn’t some of the greatest modern sculptors, including Rodin, who is often considered the single most important figure in modern sculpture, produce particular sculptures that are considered indispensable to narratives of art history? Second, why did such relatively minor sculptors as Boccioni, Smithson, and Tatlin produce individual works that are effectively judged more important than any single pieces by much greater sculptors? And third, why does the evidence of the textbooks imply that the careers of Boccioni, Smithson, and Tatlin are dominated by the individual works listed in table 6.2?

These puzzles have not been recognized by art historians, so there has been no discussion of them in the literature. Yet a resolution of all three is suggested by the analysis presented in this book. Specifically, Rodin, Brancusi, Giacometti, and Smith could be experimental innovators, who produced important bodies of work, while Boccioni, Tatlin, and Smithson could be conceptual innovators, whose contributions are dominated by individual masterpieces. Immediate support for this hypothesis is provided by table 6.2, which shows that Boccioni, Tatlin, and Smithson all produced their greatest individual works at considerably younger ages—from 31 to 35—than did Rodin, Brancusi, Giacometti, and Smith, who were from 46 to 58 when they made their most important works. Further evidence in support of the hypothesis is provided by a consideration of these sculptors’ goals and achievements.

TABLE 6.2

Single Most Frequently Illustrated Work by Each of the Sculptors in Table 6.1

Source: See table 4.6.

Rodin is celebrated for the visual sensitivity of his work: George Heard Hamilton described him as “a superb modeller, perhaps the greatest in the history of European sculpture.”3 Yet Rodin’s career, and art, developed slowly. The poet Rainer Maria Rilke, who worked for several years as Rodin’s secretary, observed that “his work developed through long years. It has grown like a forest.” The reason for this was clear to Rilke, for he explained that Rodin’s art “depended upon an infallible knowledge of the human body” that he had gained slowly and painstakingly: “His art was not built upon a great idea, but upon a craft.”4 It was not only Rodin’s craft that developed slowly, but also his individual sculptures: “I am unfortunately a slow worker, being one of those artists in whose minds the conception of work slowly takes shape and slowly comes to maturity.”5

Rodin’s art was avowedly visual: “I strive to express what I see with as much deliberation as I can.”6 Ideas did not precede form, but followed it: “One must never try to express an idea by form. Make your form, make something, and the idea will come.”7 He did not work from imagination, but always in the presence of a model: “I have no ideas when I don’t have something to copy.”8 He was incapable of planning his projects in advance and admitted, “I often begin with one intention and finish with another.”9 He routinely put aside an unfinished work “and for months I may appear to abandon it. Every now and then, however, I return to it and correct or add a detail here and there. I have not really abandoned it, you see, only I am hard to satisfy.”10

Rodin in fact became known to many of his contemporaries as a sculptor of unfinished works. In 1889, for example, Edmond de Goncourt criticized Rodin’s figures for incomplete execution: “Amidst the present infatuation with Impressionism, when all of painting remains in the sketch stage, he ought to be the first to make his name and gloire as a sculptor of unfinished sketches.”11 Although Rodin resented these charges, the historian Albert Elsen concluded, “What now seems heroic and contemporary about Rodin is . . . his passion for the act of making rather than completing sculpture. During his creative moments, the best of the artist found its outlet through his fingertips. His personal problem was in setting for himself impossible absolutes of perfection toward which he dedicated a lifetime of striving.”12

Rodin accepted a commission in 1891 for a sculpture to memorialize the great novelist Honoré de Balzac. After failing to meet a series of deadlines for the work, Rodin delivered it in 1898, when he was 58 years old. He considered the sculpture to be his most important achievement, “the sum of my whole life, result of a lifetime of effort, the mainspring of my aesthetic theory.”13 Yet when the sculpture was exhibited at the Salon of 1898 it caused a storm of protest by critics, the literary society that had commissioned it voted to dishonor its contract and refuse the sculpture, and a group of young artists actually plotted to vandalize it.14 Stung by the criticism, Rodin withdrew Balzac from the Salon and moved it to his home outside Paris. It was not cast in bronze until more than two decades after Rodin’s death.

The controversy over the Monument to Balzac resulted from its innovative synthesis of Rodin’s central contributions to sculpture. Rodin was always concerned with animating his figures, and often did this by fixing transitory gestures and poses; doing this with the figure of Balzac, whom he portrayed not in formal dress but in the monk’s robe he wore while working, in a dramatic stance, his head thrown back in a moment of creative inspiration, shocked those who expected a more conventional presentation. Rodin also used the surfaces and contours of his works to create atmospheric effects. The jagged profile of Balzac, the deep cavities of the face, and the rough surface of the robe all created sharp contrasts of light and shadow that emphasized the place of the figure in its environment, but also made the statue ugly to many viewers.

Rodin’s willingness to break with basic conventions of monumental sculpture made Balzac a seminal contribution to modern art. He understood that this achievement was a product of his years of work and study. On a trip to Amsterdam in 1899, Rodin saw several of Rembrandt’s greatest paintings and asked how old the artist had been when he made them. When told that they were late works, Rodin remarked, “Of course, this is not the work of youth. . . . [H]ere he was free, he knew what to keep and what to sacrifice.” When a friend asked if he saw parallels between the late Rembrandts and his own Balzac, Rodin replied that he did: “I, too, was forced to stretch my art in order to reach the kind of simplification in which there is true grandeur.”15

Early in his career Constantin Brancusi worked briefly in Rodin’s studio, but he soon left, explaining that “nothing grows under big trees.”16 Brancusi became an important sculptor by reacting against Rodin’s style, but he realized how much he owed to Rodin, as late in his career he wrote, “Without the discoveries of Rodin, my work would have been impossible.” Rudolf Wittkower explained that Brancusi’s work was based on the fragmentary partial figures pioneered by Rodin: “The discovery that the part can stand for the whole was Rodin’s, and Brancusi along with scores of other sculptors accepted the premise.”17 Brancusi’s distinctive contribution was to develop an abstract form of sculpture, but he did this visually: the source of his inspiration was always real, and his forms always originated in human and natural biology. Early in his career he also developed the novel approach of working directly in stone. Unlike Rodin, whose plaster sculptures were translated to marble by technicians with the help of mechanical “pointing” devices, Brancusi himself cut directly into the stone.18 He furthermore did this without advance planning: “I don’t work from sketches, I take the chisel and hammer and go right ahead.” This direct approach became a philosophy as well as a method: “It must be understood that all those works are conceived directly in the material and made by me from beginning to end, and that the work is hard and long and goes on forever.”19

Brancusi worked by progressively simplifying a real form; he described his art as a search for “the essence of things.”20 Sidney Geist observed that his approach gave Brancusi’s career a distinctive shape, as he worked in series with themes that evolved gradually:

Brancusi has the curious faculty of continuing old themes while developing new ones, of recapitulating his past in terms that keep pace, as it were, with the evolving present. Thus the motif of The Kiss is pursued for a span of over thirty-five years, always recognizably The Kiss, always in stone, foursquare, and resting on a flat bottom, but undergoing changes of proportion, degree of stylization, and function. Twenty-seven related Birds, made in the course of thirty years, comprise a series that slowly changes in form and meaning and culminates in a version three times as tall as the first. Mlle. Pogany, in three marble versions and nine casts in bronze made between 1912 and 1933, maintains the same size while the motif is revised to a state just this side of abstraction.

Geist also noted a consequence of Brancusi’s gradual evolution: “Just as there are no unsuccessful Brancusis or grave lapses in quality, so there are no towering peaks whose achievement sets them apart from the rest.”21

Henry Moore summarized Brancusi’s significance in modern sculpture: “Since the Gothic, European sculpture had become overgrown with moss, weeds—all sorts of surface excrescences which completely concealed shape. It has been Brancusi’s special mission to get rid of this overgrowth, and to make us more shape-conscious. To do this he has had to concentrate on very simple direct shapes.”22 Brancusi’s long experimental career appears as an extended visual process of gradually purifying and simplifying forms in pursuit of more direct shapes.

Umberto Boccioni’s career as a sculptor differed radically from those of Rodin and Brancusi. In contrast to the gradual development of their plastic styles over the course of long lives dedicated to work and study, Boccioni sculpted for barely one year and produced a total of just a dozen sculptures. Remarkably, however, table 6.2 shows that one of those sculptures has become one of the most celebrated works of art of the twentieth century.

Boccioni was a young painter in 1909 when he and a few artist friends joined Futurism, which had initially been founded by the Italian poet F. T. Marinetti as a literary movement. One of Marinetti’s central themes was the beauty of speed, so a primary concern of the Futurist painters became the visual representation of the experience of movement. One of their goals was to portray motion as a process that occurred over time, while another was to represent the tendency of motion to destroy the concreteness of forms.23 As a Futurist Boccioni quickly adopted a highly conceptual approach to art, as he wrote to a friend that his new painting was “done completely without models. . . . [T]he emotion will be presented with as little recourse as possible to the objects that have given rise to it.”24

Late in 1911 Boccioni visited Paris, where he saw new Cubist techniques that he quickly adapted to Futurist ends in his paintings. While in Paris Boccioni also became aware that there was not yet a Cubist school of sculpture, and that sculpture had consequently lagged behind painting in the development of advanced art. A consequence of this was that he might make an immediate impact on the art world by extending the concerns of Futurism to sculpture.25 Boccioni wasted little time in doing this. Following Marinetti, Futurist artists had used a novel conceptual practice from the start, in which polemical written manifestos accompanied, or even preceded, actual works of art. In keeping with this approach, in April 1912 Boccioni published a manifesto proposing a Futurist sculpture. He then proceeded to learn how to make sculptures.26

A year later Boccioni exhibited 11 sculptures at a Paris gallery. His work was praised by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who was also perhaps the most respected critic in Paris’s advanced art world: “Varied materials, sculptural simultaneity, violent movement—these are the innovations contributed by Boccioni’s sculpture.” Apollinaire teasingly referred to Unique Forms of Continuity in Space as “muscles at full speed,” but he described it as a “joyful celebration of energy.”27

Unique Forms was an imaginative synthesis, as a figure from classical Greek sculpture was transformed, with techniques taken from Cubist painting, to produce a three-dimensional representation of the visual effects of power and speed. The surfaces of the advancing figure are broken into parts, but rather than the straight lines and sharp angles of Cubism they are made into graceful curved planes. Their aerodynamic shapes appear bulky and muscular at the same time they seem to flow in the face of the strong winds created by the figure’s rapid forward movement.

Boccioni gave up sculpting after he executed Unique Forms; John Golding concluded that “with its completion, Boccioni seems to have realized that he had achieved the definitive masterpiece for which he longed.”28 Boccioni then returned to painting, in a much more conservative style, in the few years that remained before he was killed in 1916 while serving in the Italian army. In spite of the brevity of his career, Boccioni’s conceptual approach to art made it possible for him to contribute a seminal work to modern sculpture at the age of 31, after just one year of experience in that art.

Early in his career as a painter in Moscow, Vladimir Tatlin developed the conceptual philosophy that the artist should rely not only on vision, but also on knowledge—of proportion, geometry, and materials. A visit to Paris in 1913, where he saw new reliefs made by Picasso, as well as the work of Boccioni and other sculptors influenced by Cubism, had a profound impact on Tatlin’s art, as he returned to Moscow a sculptor.29 During the next few years, Cubism served as a point of departure for his efforts to organize heterogeneous materials into three-dimensional collages through the systematic use of geometry. Tatlin’s reliefs were carefully planned, based on preparatory studies and drawings.

After the 1917 Revolution, Tatlin became a leader of Constructivism, based on his conviction that art should have a social purpose. In 1919, the Soviet government commissioned him to make plans for a monument to the Third International, which Lenin had recently founded to promote global revolution. For this purpose Tatlin designed a tower that, at 1,300 feet, would have been the tallest structure in the world.

Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International was actually designed as a building that would house the Third International. His conceptual approach to art was reflected in the many layers of symbolism embodied in his plan.30 Thus, for example, the tower appeared to lean forward, befitting a progressive new form of government. The spiral shapes incorporated into the design were symbols of rising aspirations and triumph; the use of two spirals symbolized the process of dialectical argument and its resolution. Unlike earlier, static governments, which were housed in heavy, immobile structures, the dynamic new communist government should have a mobile and active architecture. The lowest level of the tower, where the congresses of the International would meet, would rotate completely on its axis once in the course of a year; the second level, which would house the International’s administrative offices, would revolve once a month; and the highest, third level, which would house the information offices of the International, would revolve daily. The diminishing size of the higher floors reflects the progression of power, up from the large hall of the assembly to smaller and more authoritative bodies at the higher levels.

Tatlin was not an engineer, and his design for the tower was highly impractical. As John Milner observed, “It was the idea and not the mechanistic realities which were his prime concern: as engineering, the tower is utopian.”31 Tatlin’s tower, which was to straddle the Neva River in Petrograd, was never built. Yet photographs of its model, and of later models that were made after the original was lost, were widely reproduced in pamphlets and books from an early date, for the design’s embodiment of the idea that advanced art could serve the purposes of modern society. The critic Robert Hughes concluded that Tatlin’s Monument “remains the most influential non-existent object of the twentieth century, and one of the most paradoxical—an unworkable, probably unbuildable metaphor of practicality.”32

Early in his career Alberto Giacometti was the most prominent Surrealist sculptor and made symbolic works in keeping with the movement’s concern with epic subjects. As he grew older, however, he left Surrealism and became increasingly concerned with problems of perception. He became aware that he had been working in a tradition of sculpture, from classical times through Rodin and beyond, that represented not simply what the sculptor sees, but also what he knows about figures, including their volume, substance, and size. Giacometti made it his goal to eliminate the conceptual elements in this traditional approach in favor of a genuinely perceptual method, in which he would model figures as they actually appeared to him—human beings, usually in motion and situated at a specific distance from him, seen from a single viewpoint, and taken in as a unified whole at one glance.33 As Giacometti stated his intention, “What is important is to create an object capable of conveying the sensation as close as possible to the one felt at the sight of the subject.”34 Part of the problem was to capture the dynamic nature of perception. Thus Jean-Paul Sartre, who was a friend of Giacometti’s, explained in an essay on his art that “for three thousand years, sculpture modelled only corpses. . . . [T]here is a definite goal to be attained, a single problem to be solved: how to mold a man in stone without petrifying him?”35

Giacometti became known for constantly revising his sculptures, which he usually did by completely destroying and re-creating them. He did not feel it necessary to preserve most of his efforts because he considered them failures. Thus, for example, in 1964, at the age of 63, he told an interviewer, “If I ever succeed in realizing a single head, I’ll probably give up sculpture for good. . . . In fact, since 1935, this is what I’ve always wanted to do. I’ve always failed.”36 Sartre contended that the impermanence and contingency of Giacometti’s sculptures brought them closer to life: “I like what he said to me one day about some statues he had just destroyed: ‘I was satisfied with them but they were made to last only a few hours’. . . . Never was matter less eternal, more fragile, nearer to being human.”37 Giacometti recognized that uncertainty was basic to his enterprise: “I don’t know if I work in order to do something or in order to know why I can’t do what I want to do.”38

In 1947 Giacometti produced the first of the tall, thin figures with ravaged surfaces that would characterize his work from then on. Making their first appearance so closely in the wake of World War II, these figures have appeared to invite interpretation as representations of survivors of the Holocaust. Giacometti denied that this was his conscious intent: “I never tried to make thin sculptures. . . . They became thin in spite of me.”39 In part because of Sartre’s identification of Giacometti as an existentialist artist, his sculptures were widely taken to represent lonely, isolated, and alienated beings of the postwar era. Yet Sartre himself noted that the appearance of Giacometti’s elongated forms is not unrelievedly gloomy, but is more complex, and presents a fundamental ambiguity: “At first glance we are up against the fleshless martyrs of Buchenwald. But a moment later we have a quite different conception; these fine and slender natures rise up to heaven . . . they dance.”40

As a college student, David Smith spent a summer working on the production line of an automobile factory. Years later, when he settled on welding steel as his favored method of making sculpture, he recalled that his time at Studebaker had prepared him for the aesthetic possibilities of industrial techniques and materials.41

Smith developed as an artist in New York in the 1930s and ’40s, in close contact with the Abstract Expressionist painters. Although Smith later told an interviewer that they had not directly discussed their work, “we did spring from the same roots and we had so much in common and our parentage was so much the same that like brothers we didn’t need to talk about the art.”42 Like many of the Abstract Expressionists, Smith arrived at his mature style in the early 1950s. This involved a distinct change in his working methods. Whereas he had previously made careful plans for his sculptures, by the mid-1950s he had become committed to discovering forms directly through improvisation. He also began to work explicitly in series. Thus after 1950 he generally titled his sculptures with the name of a series—for example, Tanktotem, Voltri, Cubi—followed by a roman numeral marking the work’s place in the sequence.43

Smith’s experimental approach of the 1950s and ’60s closely resembled that of the Abstract Expressionists. His sculptures were not the product of conscious planning: “They can begin with a found object; they can begin with no object; they can begin sometimes even when I’m sweeping the floor and I stumble and kick a few parts that happen to be thrown into an alignment that sets me off on thinking.”44 Once under way, his work was not systematic: “If I try to tell how I make art, it seems difficult. There is no order in it. . . . I have no noble thought process or concept.” His works were all connected: “The work is a statement of identity, it comes from a stream, it is related to my past works, the three or four works in process and the work yet to come.” No individual work made a complete statement: “In a sense a work of art is never finished.”45 Smith himself could never make a conclusive statement: “The trouble is, every time I make one sculpture, it breeds ten more, and the time is too short to make them all.”46 Making art was at best a process of incremental improvement: “I do not look for total success. If a part is successful . . . I can still call it finished, if I’ve said anything new.”47 Above all, however, Smith’s pleasure in his art was visual: “I like outdoor sculpture and the most practical thing for outdoor sculpture is stainless steel, and I made them and I polished them in such a way that on a dull day, they take on the dull blue, or the color of the sky in the late afternoon sun, the glow, golden like the rays, the colors of nature. . . . They are colored by the sky and surroundings, the green or blue of water.”48

Central elements of Smith’s major contribution in sculpture were drawn visually from painting. Smith believed that the shapes of modern sculpture had a single source: “We come out of Cubism.”49 Like paintings, his sculptures generally face the viewer frontally.50 Their structures often include frames, or variations on rectangular bounds. And like many Abstract Expressionist paintings, his sculptures often have no central focal point, but are based on allover compositions.51 The swirling patterns Smith wire-brushed onto the surfaces of his great late series, the Cubis, echo the gestural brushstrokes of the Abstract Expressionists, and the large sizes of these imposing works parallel those of the late canvases of many of the painters of that school.

Robert Smithson was a pioneer of the Earth art movement of the 1960s, in which a group of young artists decided not only to place their art in the landscape, but to use the landscape itself to make their art. As a sculptor in New York, Smithson was the first to use the term “earthwork” to refer to the objects he and his friends created in remote areas.52 In Smithson’s practice, Earth art became a highly complex conceptual activity that involved not only constructing large-scale monuments from earth and stone, but also writing theoretical texts that analyzed the origins and meanings of these monuments, and making extensive photographic and other documentation of the monuments. Smithson planned his projects meticulously, by mapping and photographing potential sites, and drawing sketches and blueprints of the works.53 Smithson’s death, at the age of 35, was in fact caused by the preparatory work for Amarillo Ramp, a circular form that was to be built in a small lake on a ranch in west Texas. After marking the shape of the planned sculpture, Smithson wanted to photograph the design of the piece from the air, and he was killed, along with the pilot and the owner of the ranch, when the small plane hired for the purpose crashed into a hillside.54

Smithson’s masterpiece, Spiral Jetty, projects into the north arm of Utah’s Great Salt Lake in an isolated area called Gunnison Bay. After Smithson staked out its form, the 1,500-foot-long jetty was created in April 1970, when two dump trucks, a tractor, and a front loader were used to move more than 6,500 tons of mud, salt crystals, and rock. The construction of the jetty was filmed by a professional photographer according to detailed plans Smithson made for the treatment.55 Two years later Smithson published an essay on the jetty that referred to a variety of his interests, including entropy, archaeology, astronomy, geology, modern painting, cartography, philosophy, biology, photography, physics, and paleontology; in the essay he associated the jetty’s spiral shape variously with the solar system, the molecular structure of the salt crystals found in the Great Salt Lake, Brancusi’s sketch of James Joyce, the reels of movie film used to document the work, the propeller of the helicopter he used to survey the work, a painting by Jackson Pollock titled Eyes in the Heat, the ion source of a cyclotron, ripples in the water of the Great Salt Lake, and other images that are presented in rapid-fire prose.56

Although Smithson recognized that Spiral Jetty would be submerged periodically when the lake’s level rose, he may have miscalculated how common this would be, for the jetty was hidden almost continuously between 1972 and the summer of 2002, when a drought occasioned its reappearance. Even after it reemerged, relatively few people visited it, for it is accessible only by 16 miles of gravel road that lie between the Great Salt Lake and Utah State Route 83. In spite of the fact that few people have actually seen it, however, the intellectual appeal of Smithson’s writings and the striking photographs of the jetty have helped to place it firmly in the canon of contemporary art, and Spiral Jetty has become the single work by an American artist of any period that is most likely to be reproduced in textbooks of art history.57

This survey of the careers and methods of seven important modern sculptors supports the answer suggested earlier to the puzzles noted at the outset of this section. Rodin, Brancusi, Giacometti, and Smith were experimental artists, who worked by trial and error toward imprecise visual goals. Their incremental approach, and their frequent production of series of closely related works, meant that their innovations appeared gradually in large bodies of work. Experimental innovations are generally the product of extended research, and it is therefore not surprising that these great experimental sculptors made their most important works relatively late in their careers. In contrast, Boccioni, Tatlin, and Smithson used their art to express new ideas. The most radical new ideas tend to occur early in conceptual artists’ careers, and this is consistent with the early ages at which these important conceptual sculptors produced their masterpieces.

Poetry is not a turning loose of emotion, but an escape

from emotion; it is not the expression of personality,

but an escape from personality.

T. S. Eliot, 191958

No tears in the writer, no tears in the reader.

Robert Frost, 193959

Each year since 1988, a different American poet has served as guest editor for a series of books titled The Best American Poetry. For the 2000 edition David Lehman, the series editor, asked each of the past guest editors to list what they considered the best 15 American poems of the twentieth century. Ten of the guest editors submitted such lists, and these were published, together with a similar list chosen by the series editor.60

If we consider the entries on the lists as votes, The Waste Land ranks as the most important single poem, by appearing on 5 of the 11 lists. Overall, however, the total of 9 votes for T. S. Eliot’s poems places him below several other poets, including Robert Frost, who received 11 votes, and Wallace Stevens, who received 10. Yet no single poem by either Frost or Stevens appears on more than two lists. Lehman recognized that this posed a puzzle, as he observed that although the greatness of Frost and Stevens was widely recognized, there was no agreement as to which of their poems was paramount.61

Lehman did not consider why a single poem by Eliot accounted for more than half of the total votes he received, or why Frost and Stevens appear to have been masters without masterpieces. The analysis presented in this book, however, suggests the explanation that Eliot was a conceptual innovator, while Frost and Stevens were experimental innovators. A recent quantitative study of the careers of modern American poets supports this explanation for these three poets and more broadly demonstrates the applicability of this analysis to poets. Its results can be surveyed in part here.

The distinction between conceptual and experimental poets is closely related to that for painters. Conceptual poetry typically emphasizes ideas or emotions, and often involves the creation of imaginary figures and settings, whereas experimental poetry generally stresses visual images and observations, based on real experiences. Conceptual poetry often stems directly from a study of earlier poetry, while experimental poetry is more often motivated by perception of the external world. Conceptual poetry is more often abstract, and aimed at universality, while experimental poetry is generally concrete, and concerned with specifics. Conceptual poets are more likely to compose deductively, effectively working backward from a preconceived conclusion, whereas experimental poets often wish to find the conclusion of a poem during the process of composition. Conceptual poets may privilege technique and use formal or artificial language, whereas experimental poets are more likely to emphasize subject matter, and to use vernacular language.

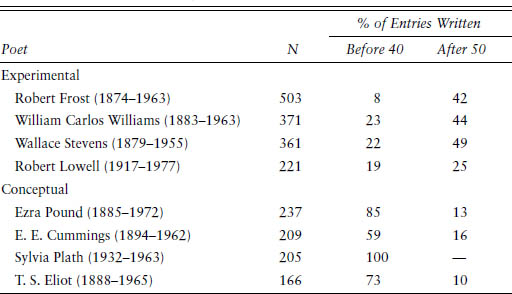

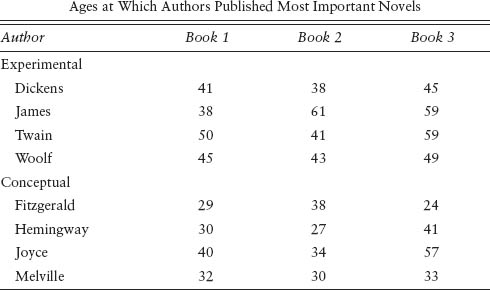

The quantitative analysis of poets’ careers that will be presented here is based on examination of 47 anthologies of poetry, published since 1980, that survey at least the entire modern era.62 Eight modern American poets will be considered here, and table 6.3 demonstrates that they are all clearly considered important by the editors of the anthologies. Thus each has an average of more than three poems reprinted in the 47 anthologies, four of the eight have an average of more than five poems reprinted, and Frost remarkably has an average of more than ten poems reprinted.

Before examining the quantitative evidence, a consideration of the nature of the work of these eight poets can serve to categorize them as conceptual or experimental. Chronologically, the first of the eight is Robert Frost. Frost made the people of New England his subject, as his metered rhythms transformed their conversational language and diction into poetry. Although he was never entirely dedicated to farming, Frost did run a chicken farm in New Hampshire early in his career. Robert Lowell believed that this experience allowed Frost to find his true subject: “These fifteen years or so of farming were as valuable to him as Melville’s whaling or Faulkner’s Mississippi.” After Frost’s death, Lowell recalled that “what I liked about Frost’s poems when I read them thirty years ago was their description of the New England country. . . . I used to wonder if I knew anything about the country that wasn’t in Frost.”63

TABLE 6.3

Total Anthology Entries for Selected American Poets

Source: Galenson, “Literary Life Cycles,” tables 4, 6.

Randall Jarrell wrote of Frost in 1963, “No other living poet has written so well about the actions of ordinary men,” and commented on his “many, many poems in which there are real people with their real speech and real thought and real emotions.”64 Frost himself declared that his poetry was inspired by real speech: “I was under twenty when I deliberately put it to myself one night after good conversation that there are moments when we actually touch in talk what the best writing can only come near.” Frost based his poetry on what he called “sentence-sounds,” by which he meant the impact of the rhythms and stress patterns within sentences on the meanings of the words they contained. Capturing sentence-sounds was not a process of imagining, but of listening: “They are gathered by the ear from the vernacular and brought into books. . . . I think no writer invents them. The most original writer only catches them fresh from talk, where they grow spontaneously.”65 The language of Frost’s poems equally came from listening: “I would never use a word or combination of words that I hadn’t heard used in running speech.”66

Frost believed that poems should not be planned or rehearsed, but that their composition should be a process of discovery: “When I begin a poem I don’t know—I don’t want a poem that was written toward a good ending. . . . You’ve got to be the happy discoverer of your ends.”67 A poem would retain its impact on the reader only if the poet himself had not anticipated the poem’s development: “No surprise for the writer, no surprise for the reader. . . . It can never lose its sense of a meaning that once unfolded by surprise as it went.”68

Frost’s poetry matured slowly. Lowell attributed this to his experimental method: “Step by step, he had tested his observation of places and people until his best poems had the human and seen richness of great novels.”69 Frost believed strongly that the wisdom that came from experience was more valuable than the more intense but less sustained brilliance of youth. Thus at the age of 63 he wrote, “Young people have insight. They have a flash here and a flash there. . . . It is later in the dark of life that you see forms, constellations. And it is the constellations that are philosophy.”70

Wallace Stevens’s elegant and complex poetry drew heavily on his imagination, but he emphasized that his poems grew out of real experiences. He once wrote to a friend, “While, of course, my imagination is a most important factor, nevertheless I wonder whether, if you were to suggest any particular poem, I could not find an actual background for you. . . . The real world seen by an imaginative man may very well seem like an imaginative construction.”71 Stevens in fact considered it essential for poems to have a basis in reality, as he wrote in one essay that “the imagination loses vitality as it ceases to adhere to what is real,” and declared elsewhere that “poetry has to be something more than a conception of the mind. It has to be a revelation of nature.”72

Stevens did not make plans or outlines for his poems, but improvised as he wrote.73 Glen MacLeod has compared Stevens’s method of finding a poetic subject to the automatism practiced by such experimental painters as Joan Miró and Robert Motherwell: “The artistic process is the same in both cases: The artist manipulates the medium—colors and forms in the case of Motherwell, sounds and images in the case of Stevens—intensely scrutinizing his own emotional responses, until suddenly, automatically, the desired subject manifests itself. . . . Like Motherwell’s method of painting, Stevens’ poetic process is close in spirit to the automatism of the absolute surrealist Miró.”74 Stevens’s poems developed gradually; he once explained, “I start with a concrete thing, and it tends to become so generalized that it isn’t any longer a local place.”75 After examining manuscript variations of two of Stevens’s poems, George Lensing observed, “Stevens here struggles with the problem of concluding both poems. . . . But the movement from the obvious mediocrity of the alternates to the final versions reveals the sure hand of the artist advancing through trial and error to the most forceful result.”76

A number of critics have observed that Stevens’s poetry matured slowly and continued to develop throughout his career. On the occasion of Stevens’s 75th birthday, William Carlos Williams described the strengths of Stevens’s work, then noted:

This power did not come to Stevens at once. Looking at the poems he wrote thirty years ago . . . Stevens reveals himself not the man he has become in such a book as The Auroras of Autumn [published at age 71] where his stature as a major poet has reached the full. It is a mark of genius when an accomplished man can go on continually developing, continually improving his techniques as Stevens shows by his recent work. Many long hours of application to the page have gone into this. . . . Patiently the artist has evolved until we feel that should he live to be a hundred it would be as with Hokusai a perspective of always increasing power over his materials until the last breath.77

Randall Jarrell similarly observed that “Stevens did what no other American poet has ever done, what few poets have ever done: wrote some of his best and newest and strangest poems during the last year or two of a very long life.”78 Stevens himself revealed an experimentalist’s understanding of the process of development when, at the age of 63, he observed that “the poems in my last book are no doubt more important than those in my first book, more important because, as one grows older, one’s objectives become clearer.”79

William Carlos Williams’s lifelong goal was to invent a new poetry “rooted in the locality,” which would “embody the whole knowable world about me.”80 He wanted to use everyday American speech to portray the essence of everyday American experience. Williams strongly objected to the abstraction of the poetry of his contemporaries Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot, declaring instead, “That is the poet’s business. Not to talk in vague categories but to write particularly, as a physician works upon a patient, upon the thing before him, in the particular to discover the universal.”81

The metaphor was not casually chosen, for Williams spent nearly his entire adult life as a doctor in a small town in New Jersey. Rather than believing that his medical practice detracted from his poetry, he considered the two complementary: “As a writer I have never felt that medicine interfered with me but rather that it was my very food and drink, the very thing which made it possible for me to write. Was I not interested in man? There the thing was, right in front of me. I could touch it, smell it.”82 Randall Jarrell recognized this as a virtue of his poetry: “Williams has the knowledge of people one expects, and often does not get, from doctors; a knowledge one does not expect, and almost never gets, from contemporary poets.”83

Williams was not precocious or facile as a poet. His college friend Ezra Pound praised an early work of Williams for its seriousness, but poked fun at its form, commenting, “I do not pretend to follow all of his volts, jerks, sulks, balks, outbursts and jump-overs.”84 But many poets would later find the strength of Williams’s poetry in concreteness and observation. Jarrell observed, “The first thing one notices about Williams’s poetry is how radically sensational and perceptual it is: ‘Say it! No ideas but in things.’ ”85 Even more simply, James Dickey wrote that “if a man will attend Williams closely he will be taught to see.”86 Wallace Stevens stressed the connection between vision and Williams’s incremental method: “Williams is a writer to whom writing is the grinding of a glass, the polishing of a lens by which he hopes to be able to see clearly. His delineations are trials. They are rubbings of reality.”87 The primacy of perception marks Williams clearly as an experimental poet. Thus Jarrell grouped him with two other experimentalists: “Williams shares with Marianne Moore and Wallace Stevens a feeling that nothing is more important, more of a true delight, than the way things look.”88 Robert Lowell placed Williams with yet another experimental poet, as he concluded a review of the first section of Paterson, published when Williams was 63, by remarking that “for experience and observation, it has, along with a few poems of Frost’s, a richness that makes almost all other contemporary poetry look a little secondhand.”89

Ezra Pound published five volumes of poems by the age of 30, and this early output was marked by “an astonishing display of variety and versatility,” with “poems in a wide range of styles and modes.”90 His achievement was primarily in technique: “Pound is more interested in the technical elements of the poem than its subject. His poetry of this period is a learned poetry rather than one that grows from personal experience.”91 Pound famously edited The Waste Land, cutting more than half of Eliot’s original version to create a sharper and more forceful poem. In gratitude, Eliot later dedicated the poem to Pound with the tribute “il miglior fabbro”—the better craftsman—explaining that he wished “to honor the technical mastery and critical ability in [Pound’s] own work.”92 Yet even Eliot admitted that his interest in Pound’s work was almost exclusively in its form: thus Eliot wrote, “I confess that I am seldom interested in what Pound . . . is saying, but only in the way he says it.”93

At the age of 28 Pound conceived a new type of poetry he named Imagism. In keeping with Pound’s conceptual approach, he published a set of formal rules for this new poetry. The motivation for the movement lay in thought rather than observation: as the critic Hugh Kenner explained, “The imagist . . . is not concerned with getting down the general look of the thing. . . . The imagist’s fulcrum . . . is the process of cognition itself.”94

Pound’s erudition helped make him extremely influential as a critic as well as a poet early in his career. But the use he made of his erudition was sometimes faulted. As early as 1922, Edmund Wilson remarked on Pound’s “peculiar deficiencies of experience and feeling,” and his tendency always to return to literary history: “Everything in life only serves to remind him of something in literature.”95 A few years later Conrad Aiken made a similar criticism, noting that Pound’s work was “curiously without a center”: “He has nothing to say of his own day and age; he prefers to try on, one after another, the styles of the ancients . . . can one not—he says in effect—make a poetry of poetry, a literature of literature?”96 Experimental poets deplored Pound’s influence, as, for example, William Carlos Williams described Pound, and Eliot, as little more than scholarly plagiarists: “Eliot’s more exquisite work is rehash, repetition in another way of Verlaine, Baudelaire, Maeterlinck—conscious or unconscious—just as there were Pound’s early paraphrases from Yeats and his constant later cribbing from the Renaissance, Provence and the modern French: Men content with the connotations of their masters.”97 Interestingly, late in his life Pound may have come to agree with the critics who complained of a lack of content in his poetry. Thus a friend reported that in 1966, when Pound was 81, the poet declared that the Cantos, which had occupied him for much of his life, were a failure, explaining, “I knew too little about so many things. . . . I picked out this and that thing that interested me, and then jumbled them into a bag. But that’s not the way to make a work of art.”98

T. S. Eliot wrote “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”—“a poem that has become perhaps the most famous ever written by an American”—at the age of 23, while he was a graduate student in philosophy at Harvard.99 The breakthrough that allowed Eliot to produce this early masterpiece was the result of his discovery two years earlier of the work of the nineteenth-century French Symbolist poet Jules Laforgue. Eliot later recalled that his first reading of Laforgue “was a personal enlightenment such as I can hardly communicate,” as he had “changed, metamorphosed almost, within a few weeks even, from a bundle of second-hand sentiments into a person.”100 Noting the technical mastery and sophisticated tone of Eliot’s early work, one scholar commented that he “seems never to have been a young man.”101

At the age of 34 Eliot published The Waste Land. Soon after its completion he wrote to a friend, “I think it is the best I have ever done.”102 It quickly established Eliot as the leading modern poet, “the counterpart in poetry to Joyce, Picasso, Stravinski, and to other major creators of the Modernist revolution in their respective arts.” It baffled many readers with its novel methods and forms. David Perkins recently surveyed some of its innovative dimensions: “The technique resembled cinematic montage. . . . It had no plot. There was no poet speaker to be identified with. . . . My point is not simply that the poem couldn’t be fitted into any known genre but that there seemed to be nothing—no narrative, meditation, flow of lyric emotion, characterization—which one could follow, thus ‘understanding’ the poem.”103 Edmund Wilson remarked on the scholarly range of The Waste Land: “In a poem of only four hundred and three lines . . . [Eliot] manages to include quotations from, allusions to, or imitations of, at least thirty-five different writers . . . as well as several popular songs; and to introduce passages in six foreign languages, including Sanskrit.” Wilson then added: “One would be inclined a priori to assume that all this load of erudition and literature would be enough to sink any writer.”104 Conrad Aiken complained that Eliot had made poetry, and its past, his real subject: “In The Waste Land, Mr. Eliot’s sense of the literary past has become so overmastering as almost to constitute the motive of the work. It is as if, in conjunction with the Mr. Pound of the Cantos, he wanted to make a ‘literature of literature’—a poetry actuated not more by life itself than by poetry. . . . This involves a kind of idolatry of literature with which it is a little difficult to sympathize.”105

The impact of The Waste Land on American poetry was immediate. William Carlos Williams later recalled that when it was published “it wiped out our world as if an atom bomb had been dropped upon it.”106 Malcom Cowley, a decade younger than Eliot, confirmed his influence: “To American writers of my own age . . . the author who seemed nearest to themselves was T. S. Eliot. . . . His achievement was the writing of perfect poems, poems in which we could not find a line that betrayed immaturity, awkwardness, provincialism, or platitude.”107 To Williams, this elegance and sophistication came at the cost of content: “We can admire Eliot’s distinguished use of sentences and words and the tenor of his mind but as for substance—he is for us a cipher.” Looking back late in his life, Williams regretted the conceptual influence of Eliot on younger poets, for with The Waste Land, “critically Eliot returned us to the classroom just when we were on the point of an escape to matters much closer to the essence of a new art form itself—rooted in the locality which should give it fruit.”108

E. E. Cummings wrote many lyric poems in a variety of styles drawn from medieval, Renaissance, and Victorian poetry. Thus, as David Perkins noted of one late sonnet, “The irregularities of meter, punctuation, typography, and word order would not be found in a nineteenth-century poet, but in diction, sentiment, and conception the stanza is traditional.” Perkins explained that Cummings’s innovations were in form:

He experimented with the ellipsis, distortion, fragmentation, and agrammatical juxtaposition that made some of his poetry difficult. He dismembered words into syllables and syllables into letters, and though this fragmentation activated rhymes and puns, the reasons for it were also typographical—the look of the poem on the page. Manipulating letters, syllables, punctuation, capitals, columns of print, indentation, line length, and white space as visual or spatial forms, Cummings arranged them in order to enact feeling and carry meaning.109

A persistent criticism of Cummings’s poems concerned the substance that lay behind his technique. So, for example, in 1924 Edmund Wilson remarked that Cummings’s “emotions are familiar and simple. They occasionally even verge on the banal.” Two decades later, F. O. Matthiessen noted that Cummings’s work represented “probably the first time on record that complicated technique has been devised to say anything so basically simple. The payoff is, unfortunately, monotony.” And another decade later, Randall Jarrell commented, “Some of his sentimentality, his easy lyric sweetness I enjoy in the way one enjoys a rather commonplace composer’s half-sweet, half-cloying melodies, but much of it is straight ham, straight corn.”110

In view of his preoccupation with form, it is not surprising that Cummings’s trademark contributions were conceptual and appeared early in his career: by the time he finished college he had “armed himself with a whole battery of technical effects” that would recur in his poetry thereafter.111 As David Perkins observed, “Critics complained that Cummings’ poetry did not develop, and he was infuriated. Yet, on the whole, the critics were right. . . . [A]ll his volumes contained the same types of poems and expressed similar attitudes.”112 When Cummings was 50, a reviewer of his latest book remarked, “The fascinating thing about Cummings is that he is always talking about growth, and always remains the same.”113 Nor was this perception restricted to Cummings’s detractors. Reviewing a book published by Cummings near the end of his life, James Dickey declared, “I think that Cummings is a daringly original poet, with more virility and more sheer, uncompromising talent than any other living American writer.” Yet Dickey opened the review by observing, “When you review one of E. E. Cummings’s books, you have to review them all. . . . His books are all exactly alike, and one is faced with evaluating Cummings as a poet, using the current text simply as a hitherto unavailable source of quotations.”114

In a recent survey, David Perkins observed that from the vantage point of William Carlos Williams and his followers, T. S. Eliot “had disseminated . . . a formalism, a cosmopolitanism, and an academicism from which American poetry recovered only in the 1950s and 1960s.”115 A key figure in that later shift was Robert Lowell. Life Studies, published in 1959 when Lowell was 42, was recognized as an important achievement for its introduction of what became known as confessional poetry. Life Studies involved a loosening of Lowell’s earlier rigorously formal structure, as well as a move to more personal subject matter, as Lowell worked to give priority to substance rather than form. Its achievement was the product of a long struggle that resulted from Lowell’s dissatisfaction with the restrictions and constraints of existing poetic forms: for 18 months before writing Life Studies, Lowell wrote exclusively in prose, to allow himself to concentrate on “what is being said” rather than how it was expressed.116

The form of Life Studies reinforced its message, for as one scholar recently observed, its improvisational quality was “indicative of an individual seeking coherence in a disordered, troubled life.” Lowell’s persistent irresolution contributed to the achievement, for “one of the real triumphs of Life Studies is exactly in its creative inscription of doubt and uncertainty.”117 Lowell later explained that “in Life Studies, I wanted to see how much of my personal stories and memories I could get into poetry. To a large extent it was a technical problem. . . . But it was also something of a cause: to extend the poem to include, without compromise, what I felt and knew.”118 Yet although Life Studies won the National Book Award, true to his experimental nature Lowell remained uncertain of his accomplishment: “When I finished Life Studies I was left hanging on a question mark. . . . I don’t know whether it is a death-rope or a life-line.”119

Lowell’s methods readily identify him as an experimental seeker. In his mature work, he avoided beginning his poems with a predetermined structure, for his goal was to discover a structure in the course of composition, as he sought to articulate his memories and observations. Lowell told an interviewer that even composing new poems invariably involved changes: “I don’t believe I’ve ever written a poem in meter where I’ve kept a single one of the original lines.”120 Lowell continually revised his old poems, for “what he was after was not so much a poem as a poetic process—something that denied coherence, in the traditional sense, and closure.”121 Lowell’s friend and fellow poet Frank Bidart explained that Lowell’s constant rethinking, reimagining, and rewriting of his poems was fundamental to him throughout his career: “It proceeded very deeply from the nature of what he was doing as a writer.” For Lowell the process of changing his work was not necessarily one of improving it: “He often said that something is lost in revision even if something is gained. Each version is a journey: each occasion that he inhabited the material, slightly different.”122 As Lowell told the poet Stanley Kunitz, “In a way a poem is never finished. It simply reaches a point where it isn’t worth any more alteration, where any further tampering is liable to do more harm than good.”123 Yet Lowell always worked with the goal of discovery. He told an interviewer of his excitement when a successful struggle with form allowed him to arrive at a new statement in the process of composing a poem: “The great moment comes when there’s enough resolution of your technical equipment, your way of constructing things, and what you can make a poem out of, to hit something you really want to say. You may not know you have it to say.”124

Lowell’s poetry continued to evolve throughout his life. In 1963, when Lowell was 46, Randall Jarrell observed that Lowell was “a poet of great originality and power who has, extraordinarily, developed instead of repeating himself.”125 At the end of Lowell’s life, Donald Hall remarked that “Lowell was not the first poet to undertake great change in mid-career, but he was the best poet to change so much.”126

Lowell’s introspective writing about his own troubled life inspired many younger poets to create autobiographical works. Sylvia Plath was prominent among these, as she declared that Life Studies excited her with “this intense breakthrough into very serious, very personal emotional experience, which I feel has been partly taboo.”127 She followed Lowell in writing vividly and painfully about her own life. Her innovations, however, lay not in subject matter but in language, with “her use of metaphors so strong that they displace what they set out to define and qualify.”128 The power of her work lay in imagination: “Plath was strikingly original and fertile in imaginative invention, in metaphors and fables, and her lyrics, brief though they are, set many metaphors going at once.”129 Plath’s writing dealt openly with her mental illness and her attempts at suicide. Stephen Spender observed that Plath’s poems presented the reader with a “dark and ominous landscape. The landscape is an entirely interior, mental one in which external objects have become converted into symbols of hysterical vision.”130 Several reviewers of Plath’s late work explicitly contrasted it with Lowell’s. One commented on “her narrower range of technical resource and objective awareness than Lowell’s, and . . . her absolute, almost demonically intense commitment by the end to the confessional mode,” while another less delicately declared that “Nothing could be healthier than Lowell’s poetry . . . and likewise it is no good pretending that Sylvia Plath’s is not sick verse.”131 The poet A. Alvarez, a friend of Plath’s, recalled that when she first read him her new poems “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus” he was shocked: “At first hearing, the things seemed to be not so much poetry as assault and battery.”132 In a foreword to Ariel, a posthumous collection of Plath’s late poems, Lowell himself commented, “Everything in these poems is personal, confessional, felt, but the manner of feeling is controlled hallucination, the autobiography of a fever.”133

A. Alvarez remarked that late in her life Plath’s poetry became increasingly extreme in transforming the events of her life: “Her poetry acted as a strong, powerful lens through which her ordinary life was filtered and refigured with extraordinary intensity.”134 Similarly, a critic observed that unlike Lowell, whose poetry was intended to describe his life, and whose express intention was to make the reader “believe that he was getting the real Robert Lowell,” Plath used her life merely as a point of departure for her poems: “Unlike Lowell, Sylvia Plath was not writing a poetic autobiography but using personal experiences as a way into the poem. . . . The real Sylvia Plath is far from present in the poetry.”135

Plath’s poetry was conceptual, based on extreme emotion rather than careful observation. Her most celebrated poems date from the final two years of her life, before her suicide at the age of 30. Her arrival at her greatest work occurred abruptly: her husband, the poet Ted Hughes, later recalled that in these final two years “she underwent a poetic development that has hardly any equal on record, for suddenness and completeness.” She was not hesitant to finish her poems, as Hughes noted that the poems in Ariel were “written for the most part at great speed, as she might take dictation,” and she frequently began and completed a poem in a single day.136 Nor did she suffer from doubt about her achievement: four months before her death, she wrote to her mother, “I am a genius of a writer; I have it in me. I am writing the best poems of my life; they will make my name.”137 Plath’s prediction proved correct. Two poems written during her final months, “Daddy” and “Lady Lazarus,” are among the most frequently anthologized American poems of the twentieth century.138 It is unlikely, however, that even Plath would have predicted how widely her late poems would make her name, for Ariel would eventually sell more than a half million copies, a rare level of popular success for poetry.139

As shown in table 6.3, the evidence of the anthologies points to a sharp difference in the life cycles of the conceptual and experimental poets considered here. For the experimental poets—Frost, Lowell, Stevens, and Williams—less than a quarter of their total anthology entries represent poems they wrote before the age of 40, whereas for the conceptual Cummings, Eliot, Plath, and Pound, well over half of the total entries are for poems written before age 40. At least a quarter of the anthology entries for the four experimental poets are of poems they wrote past the age of 50—for Stevens the share is nearly one-half—whereas for Cummings, Eliot, and Pound the comparable share was less than one-sixth. Plath’s suicide at 30 obviously makes it impossible to know the path of her career if she had lived into her 70s or 80s, as did Frost and Stevens. Yet no matter what additional greatness Plath might have achieved had she survived, her early achievement was such that her career would not have resembled those of Frost and Stevens. The earliest of Frost’s poems reprinted in the anthologies was written at age 38, and the earliest of Stevens’s at 36. Had Frost or Stevens died as young as Plath, not only would we today not recognize them as great poets, we would probably not know them at all. Plath’s ability to make such a remarkable achievement in a life span of only 30 years is a direct consequence of the conceptual nature of her poetry, and her dramatic early arrival at artistic maturity.

It is an epic of two races (Israelite-Irish) and at the

same time the cycle of the human body as well as a little

story of a day (life). . . . It is also a sort of encyclopedia.

My intention is to transpose the myth sub specie

temporis nostri.

James Joyce on Ulysses, 1920140

The novel is the only form of art which seeks to make

us believe that it is giving a full and truthful record

of the life of a real person.

Virginia Woolf, 1929141

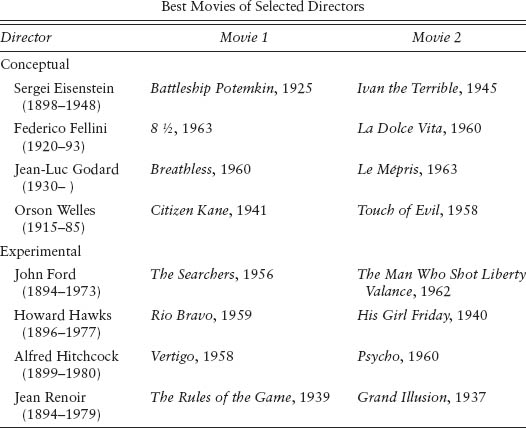

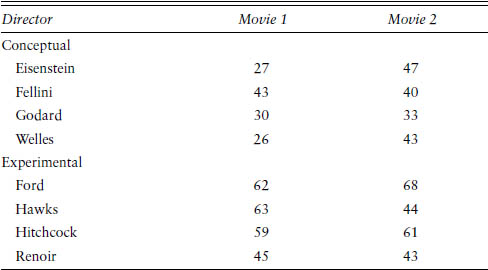

Conceptual novelists often begin from general ideas or principles. They are more likely to produce symbolic works, while experimental writers more often deal with particularized cases in a documentary fashion. The characters in conceptual novels may seem oversimplified or one-dimensional compared with those in experimental novels, who are more likely to be lifelike people seen in realistic situations. The language of conceptual authors is often formal or artificial, that of experimental authors informal or vernacular. The books of conceptual authors will more often be resolved, with clear messages or lessons, whereas experimental authors often leave their plots unresolved, their conclusions open or ambiguous.

Conceptual writers are more likely to base their works on library research and to strive for precise factual accuracy, whereas experimental writers typically rely on their own perceptions and intuitions. Conceptual authors may construct complex plots, carefully planned in advance, whereas experimental authors generally invent their plots as they write, often introducing major changes in their developing plots throughout the process of composition. For experimental writers, plots are often developed to serve the purposes of characterization and creation of atmospheric effects, whereas for conceptual writers characters and settings are more often used to achieve an overarching structure or concept. Experimental authors often believe that the essence of creativity lies in the process of writing, and that their most important discoveries are made while their books are being composed, whereas conceptual authors more often value ideas they formulated before beginning to draft their books. The clarity of conceptual authors’ goals generally allows them to be satisfied that a book is complete and has achieved a specific purpose, but experimental authors’ lack of precise goals often leaves them dissatisfied with their work. Many experimental writers consequently have trouble considering their books finished, they revise their manuscripts repeatedly, and they sometimes even return to published works to revise them further.

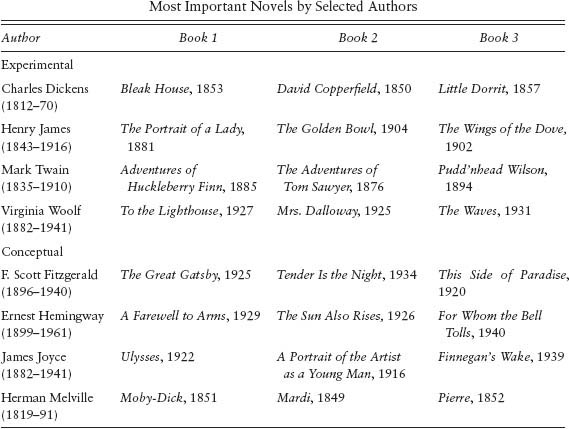

This section will apply this analytical scheme to eight British and American novelists of the past two centuries. Although this sample is not intended to represent all the most important writers of the modern period, the writers considered here were all among the most important novelists of their time.142 This discussion will examine aspects of these writers’ work that allows us to categorize them as experimental or conceptual, then will present a quantitative measure of when they produced their greatest contributions in order to examine their careers in light of the nature of their work.

Charles Dickens’s strengths and weaknesses are those of an experimental author. Virginia Woolf remarked on the visual quality of his characterizations: “As a creator of character his peculiarity is that he creates wherever his eyes rest—he has the visualizing power in the extreme. His people are branded upon our eyeballs before we hear them speak, by what he sees them doing, and it seems as if it were the sight that sets his thoughts in action.”143 Earlier Anthony Trollope had emphasized Dickens’s success in characterization: “No other writer of English language has left so many types of character as Dickens has done—characters which are known by their names familiarly as household words.”144

Henry James remarked disapprovingly that “Mr. Dickens is a great observer and a great humorist, but he is nothing of a philosopher.” Later George Santayana agreed that Dickens did not deal in abstractions but in particularities: “Properly speaking, he had no ideas on any subject; what he had was a vast sympathetic participation in the daily life of mankind.”145 Generations of critics have praised Dickens’s powers of description. In 1840 William Makepeace Thackeray observed that the Pickwick Papers “gives us a better idea of the state and ways of the people than one could gather from any more pompous or authentic histories.” In 1856 George Eliot declared, “We have one great novelist who is gifted with the utmost power of rendering the external traits of a town population.”146 A century later Angus Wilson, reflecting on “the intense haunting of my imagination by scenes and characters from Dickens’ novels,” explained that “their obsessive power does not derive from their total statements; it seems to come impressionistically from atmosphere and scene which are always determinedly fragmentary.”147

As Wilson implied, Dickens’s plots are not considered a strength. Virginia Woolf commented that “Dickens made his books blaze up, not by tightening the plot . . . but by throwing another handful of people upon the fire,” which made his novels “apt to become a bunch of separate characters loosely held together.”148 More bluntly, Arnold Kettle noted, “It is generally agreed that the plots of Dickens’ novels are their weakest feature.” G. K. Chesterton contended that most of Dickens’s books were in fact not novels, because they lacked a key requirement for that form, namely, an ending. Thus Chesterton observed of Pickwick, “The point at which, as a fact, we find the printed matter terminates is not an end in any artistic sense of the word. Even as a boy I believed that there were some more pages that were torn out of my copy, and I am looking for them still.”149

Dickens’s craft developed in a number of ways over the course of his career. He worked at improving his organization and plotting, and a number of critics have remarked on his improvement. Thus Daniel Burt recently observed that “readers interested in marking Dickens’ remarkable progression as a novelist can do no better than to compare the joyful, seemingly spontaneous generation of Pickwick [completed when Dickens was 25], in which Dickens claimed that, given his desultory mode of installment publication, no artful plot could even be attempted, with the intricate, brooding design of Bleak House [completed at 41], published in the same monthly installment form.”150 Dickens also refined his strengths over time. He excelled in capturing the speech of his characters, and particularly the colorful vernacular of the working class: “From the beginning Dickens was . . . greatly assisted by his knowledge of the speech forms of lower-class Londoners.” A linguistic analysis has shown that his use of this knowledge grew more sophisticated over the course of his career, as over time he gave larger numbers of characters personalized habits and patterns of speech, or idiolects. This produced a greater richness in the later works. Whereas in the early novels the relatively small number of characters with distinct idiolects “dominate the stage as if they were performing a solo act, . . . in the works of the final period it was no longer a question of a group of leading figures with pronounced idiolects being supported by a cast of typified ‘also-rans,’ but one of a world in which each separate character is the possessor of a sharply-delineated speech idiom which cannot be ignored.” Robert Golding consequently perceived “a stylistic development which took in Dickens’ fictional writing as a whole, one which finally succeeded in merging all the elements involved—including the idiolects—into a finely balanced whole.”151

In the summer of 1850, Herman Melville was well along on a draft of a new book on whaling when his move from New York to western Massachusetts occasioned a meeting with the distinguished older novelist Nathaniel Hawthorne. Meeting Hawthorne electrified Melville: in an essay written almost immediately thereafter, he declared, “Hawthorne has dropped germinous seeds into my soul.” In his excitement Melville predicted that “if Shakespeare has not been equalled, he is sure to be surpassed, and surpassed by an American born now or yet to be born.”152

The reference to Shakespeare was not by chance, for Melville had recently bought a complete edition of Shakespeare’s works and had reproved himself as a “dolt & ass” for not having made acquaintance earlier with “the divine William.”153 The inspiration of his new friendship with Hawthorne prompted Melville to begin a complete revision of his manuscript on whaling, using the language and tragic grandeur he found in Shakespeare. F. O. Matthiessen observed that Shakespeare’s language gave Melville “a range of vocabulary for expressing passion far beyond any that he had previously possessed.”154 The revised version of Moby-Dick consequently had an emotional intensity that was new to Melville’s work: as D. H. Lawrence later wrote, “There is something really overwhelming in these whale-hunts, almost superhuman or inhuman, bigger than life, more terrific than human activity.”155

In writing Moby-Dick, Melville continued his earlier practice of borrowing extensively from other scholarly and narrative books. Scholars have concluded that Melville relied heavily on five books for information on whaling.156 A biographer commented on Melville’s “extraordinary dependence on the writings of other men,” not only for literary means, but for the substance of his books, but noted that in his prose the bare facts of earlier authorities were transformed into metaphors and symbols: “One can never predict when some piece of pedestrian exposition will furnish him with the germ of a great dramatic scene.”157

When Moby-Dick was published in 1851, a reviewer described it as an unlikely but successful allegory: “Who would have looked for philosophy in whales, or for poetry in blubber. Yet few books which professedly deal in metaphysics, or claim the parentage of the muses, contain as much true philosophy and as much genuine poetry as the tale of the Pequod’s whaling expedition.”158 Seventy years later, D. H. Lawrence called it “one of the strangest and most wonderful books in the world . . . an epic of the sea such as no man has equalled. . . . It moves awe in the soul.”159 Alfred Kazin explained that “Moby-Dick is the most memorable confrontation we have had in America between Nature—as it was in the beginning, without man, God’s world alone—and man, forever and uselessly dashing himself against it.”160

In spite of generations of reappraisals of Melville’s later fiction and poetry, there remains widespread agreement with the observation of an admirer of Melville’s who wrote even during the latter’s lifetime that “it may seem strange that so vigorous a genius, from which stronger and stronger work might reasonably have been expected, should have reached its limit at so early a date.”161 Melville’s sudden maturation as a writer, his production at just 32 of a masterpiece that stands as a peak not only in his career, but in American literature, and his subsequent decline as a writer are all consequences of his conceptual approach to his art, as is the allegorical nature of his greatest work.

Bernard De Voto observed that “there is a type of mind, and the lovers of Huckleberry Finn belong to it, which prefers experience to metaphysical abstractions and the thing to its symbol. Such minds think of Huckleberry Finn as the greatest work of nineteenth century fiction in America precisely because it is not a voyage in pursuit of a white whale but . . . because Huck never encounters a symbol but always some actual human being working out an actual destiny.”162 Alfred Kazin agreed that Mark Twain’s “genius was always . . . for the circumstantial, never the abstract formula. . . . Mark Twain’s world was all personal, disjointed, accidental.”163

Twain is celebrated for his use of language. Lionel Trilling declared that “out of his knowledge of the actual speech of America Mark Twain forged a classic prose.”164 Kazin compared Twain’s instinct for the rhythm and emphasis of speech to that of a great experimental poet: “A sentence in Mark Twain, as in Frost, is above all a right sound.”165 The prefatory note Twain inserted in Huckleberry Finn gently alerted the reader to Twain’s craftsmanship: “In this book a number of dialects are used. . . . The shadings have not been done in a hap-hazard fashion, or by guess-work; but pains-takingly, and with the trustworthy guidance and support of personal familiarity with these several forms of speech.”166

Studies of Twain’s methods of composition clearly reveal the procedures of an experimental author. In a memoir of his friend of forty years, the novelist William Dean Howells remarked, “So far as I know, Mr. Clemens is the first writer to use in extended writing the fashion we all use in thinking, and to set down the thing that comes into his mind without fear or favor of the thing that went before or the thing that may be about to follow.”167 Many scholars have agreed with Howell’s analysis. Franklin Rogers concluded that “Twain was aware of implicit form and sought to discover it by a sort of trial-and-error method. His routine procedure seems to have been to start a novel with some structural plan which ordinarily soon proved defective, whereupon he would cast about for a new plot which would overcome the difficulty, rewrite what he had already written, and then push on until some new defect forced him to repeat the process once again.” Sydney Krause determined that “Twain learned to consider his subject, not before, but as, he wrote.”168 Victor Doyno examined the composition of Huckleberry Finn: “Twain discovered his pliable plot as he went along, writing without a definite resolution or plan in mind. His real interests were elsewhere—in writing memorable episodes and frequently in doubling the incidents or repeating the basic situation in varied forms. It is, accordingly, a supreme misreading of the novel to read for plot as plot.”169 Twain himself explained that his focus often changed as a novel progressed: “As the short tale grows into the long tale, the original intention (or motif) is apt to get abolished and find itself superseded by a quite different one.”170

Twain’s difficulties with plots often resulted in substantial discontinuities in the process of writing his novels. Scholars have long been aware, for example, that Twain worked on Huckleberry Finn over an elapsed time of nine years, and have now determined that it was written in at least three separate periods of work. The interruptions appear to have occurred when Twain reached an impasse in the story and temporarily lost interest in it.171 Twain claimed that not only was he not dismayed by having to put aside an unfinished novel, but that he actually came to expect that he would have to: “It was by accident that I found out that a book is pretty sure to get tired along about the middle and refuse to go on with its work until its powers and its interest should have been refreshed by a rest. . . . Ever since then, when I have been writing a book I have pigeon-holed it without misgivings when its tank ran dry, well knowing that it would fill up again without any of my help within the next two or three years, and that then the work of completing it would be simple and easy.”172