3 Emotional Blocks to Collective Efficacy—How Stress Shuts Down Communication

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Communication is to relationships what breath is to life.

We get together on the basis of our similarities; we grow on the basis of our differences.

—Virginia Satir

When schools embark together on a mission to engage in mindful conversations, the culture shifts from isolation to collective efficacy. By this, we mean that the staff knows how to work together to solve problems and use each member’s unique talents to create something beyond expectations. Over time, the staff learns to value the collective wisdom gained in community. The true test comes when newcomers are easily assimilated into the school culture—the benefit of a knowledge legacy. In schools with knowledge legacies, veterans will tell new teachers who to tap into to learn how to deal with everything from schedules to specific children or parents, science or math curricula, grading practices, and so forth.

A Legacy Worth Fighting For

When teachers have spent a career talking with each other about teaching and learning, they know where expertise lies within their school and how to use it to extend learning. They are aware of gaps in learning, resourceful about finding what is needed, and willing to consider multiple options. They have found excellence by adapting, perfecting, and working with others. When educators create cultures in which deep understanding about learning and teaching becomes the norm, everyone serves as a mentor. Those who join that culture are supported from Day One in ways that foster growth and development. These cultures of collective efficacy are immersive and bring out the best in all participants.

When conversational practices are mindful and focused, the energy is different—less stressful and more renewing. The difference is palpable. The challenge, we have found, is unless an educator has had the gift of working in such a culture—one of collective efficacy—it is beyond consciousness and not expected or even understood. Trying to describe collective efficacy is not unlike Bill’s experience for the first time with a California artichoke. While Diane, a Californian, extolled its virtues, Bill, as an Iowan, had never eaten an artichoke. The idea of eating a thistle was puzzling to him. Likewise, the notion that teachers can and should help change school culture to build collective efficacy can seem bewildering and overwhelming.

Initially, the small bites of artichoke seemed like not quite enough, and it was a lot of work. Finally, when reaching the center, Bill understood why the luscious heart of the artichoke is worth all the work. Similarly, when starting off with one of the conversations in this book, it will be hard work, and those experimenting for the first time will wonder if it is worth it. In sum, understanding is based on context; what we do not know, we cannot act on or, for that matter, even dream about. For this reason, we have included many stories from the field to help the reader gain an understanding about how these conversations and these strategies play out in real life in schools. We have also chosen to tell stories that demonstrate the complexity of teaching and leading—it is not just about aligning teaching to standards, as so many policy makers want to believe. Excellent teachers are lifelong learners, always seeking new ways to better meet the needs of their students. Even small timesaving techniques are skills worthy of being passed on to other teachers. This cannot happen without collaborative conversations.

The Challenge—Developing Cultures of Collective Efficacy

On the surface, collective efficacy seems desirable and even achievable. For practitioners, however, there are great challenges—specifically, the habits and norms that create a given school culture. Most school cultures have developed limited repertoires for conversing and overuse discussion, debate, and argument. These conversations serve daily life just fine but can stymie attempts to move beyond the surface and the desire to delve into learning. Over time, group members will tend to fall into habitual, unconscious patterns of talking too much or remaining silent, languishing in the world of unproductive meetings. Worse yet, in an attempt to change the norms, meetings have now become professional learning communities (PLCs). The problem is that giving collaboration a new name does not change the personal habits. What does change habits are experiences that allow PLCs to gain understanding and insight into their own and others’ behaviors. This requires a commitment to break nonproductive habits in order to find internal and external resources that lead to solutions.

Efficacy was first labeled by Albert Bandura (1993) of Stanford University as a way of describing social learning theory. He defined efficacy as “the belief in an individual’s ability to succeed and to follow through.” Later, Goddard, Hoy, and Woolfolk (2000) of The Ohio State University expanded the theory to include group behaviors. They demonstrated a strong link between collective efficacy and student achievement. They defined collective efficacy as “the belief by the faculty as a whole that they will have a positive impact on students.” Goddard and colleagues (2004) summarize their findings and argue that collective teacher efficacy is essential for student achievement because it transcends student socioeconomic status (SES) and prior learning. The power of collective efficacy is that teacher belief systems transcend the limitations of low-SES schools. Recently, Hattie (2015) ranked collective teacher efficacy as the number-one factor that impacts student achievement. These findings are significant because the development of collective efficacy is something that schools can control. Quite simply, a culture of collective efficacy is the result of faculty interactions. To summarize: Teacher efficacy is within our collective control, unlike poverty or other blocks to learning that are conditions outside of available spheres of influence.

The real problem lies in the lack of the leadership understanding of how to create cultures that promote collective efficacy. Both of us found the best place to start was in meetings. Often when working with teachers, we use one of these Nine Conversations as a way to explore some aspect of teaching and learning. Once teachers get a taste of this new way of conversing, they want more. One teacher lamented, “I wish one of you would come and whisper in my principal’s ear during staff meetings. He just doesn’t get it, and as a result, our staff meetings are stressful and nonproductive.”

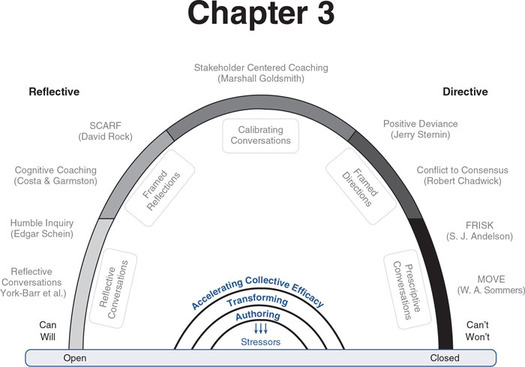

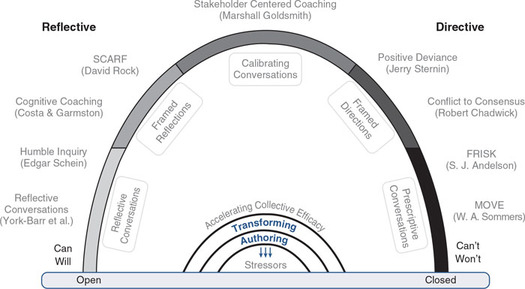

In the center of the Dashboard is the goal of this book, Accelerating Collective Efficacy. Under this title is a smaller set of arcs that point to the corrosive effect of stress and the need for groups to learn to self-author and self-transform. This chapter describes how stress is manifest in groups and creates habit-based cultures that can become rigid and inflexible—the opposite of efficacy.

Nine Professional Conversations to Change Our Schools

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

A First Step—Removing the Barriers of Stress

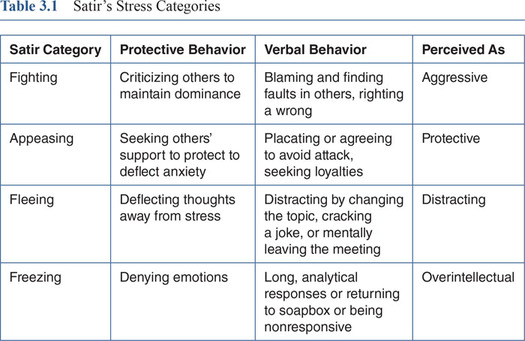

When groups have limited conversational moves, it is no wonder that meetings become stressful. In humans, the stress response triggers protective behaviors that are self-serving and, as a result, deflect group efficacy. Years ago, renowned therapist Virginia Satir (1972) observed four stress reactions in humans that created vicious cycles of miscommunication. These emotional, protective responses limit human growth and stymie the capacity for individuals to develop. It is worth explicating these defensive behaviors here as it helps individuals and groups understand how these protective habits become embedded in cultures, making them resistant to change. Being conscious of how we respond to stress helps groups notice when trust is breaking down and when it is time to slow down and check in with group members to find out what is going on in their minds.

Satir’s (1972) great gift was that she noticed four overt stress reactions in her work with clients—blaming, placating, distracting, or computing. Satir noted that these defensive habits existed below consciousness and were not obvious; by labeling them for her clients, she made them obvious. By making these habits explicit, Satir made great gains in couples counseling. We have observed all of these same responses during our collaborations with professionals. These outward manifestations are emotional responses and coping mechanisms—responses to stress—and have been observed in verbal responses during meetings. A short snippet from a staff meeting is relayed in Box 3.1 and shows how all four of these stress responses can be exhibited in one meeting. This could be any staff meeting, anywhere.

Box 3.1 Example of Staff Meeting Stress Responses

In a staff meeting, teachers are responding to this agenda item: “Pick a schoolwide theme to support the Next Generation Science Standards.”

- ■ Dan is frustrated that the topic has dragged on for over thirty minutes and his colleagues continue to argue. Dan bursts out, “I am tired of these mandates from the district office that just waste our time.” (Blame)

- ■ Several teachers nod. (Placate)

- ■ Julie, the staff joker, cracks, “Never a dull moment in Peoria! What else is new?” (Distract)

Everyone laughs, and a few shift uneasily.

- ■ Addison chimes in with a flat voice, describing a favorite theme: “I have been thinking about this for a long time, and the rainforest is the most logical choice because it embodies all the sciences such as biology, chemistry, geology, zoology, and ecology.” (Compute)

Several teachers exchange glances, silently communicating, “Not again.” They have heard this before.

The end result? This group is stuck.

In sum, our lives are stressful, and these protective responses show up for all of us. We each develop our preferred style of responding. Just as in couples counseling, our verbal responses in meetings signal our stress. The goal here is to learn how to manage the context and create what psychologists call a safe “holding environment”—that safe space for growing and learning. The holding environment was first defined by Winnicott, a British pediatrician who was tasked with creating emotional safety for babies separated from their mothers during World War II. In his clinic, they literally held the babies.

When used in relation to adult psychology, a holding environment describes interactive space that promotes trust and emotional containment. Emotional containment is the active process of slowing down, recognizing and accepting our feelings, and finding proactive ways to use the energy generated by the emotional tensions. This literally means that leaders and groups must learn to attend to and change the surroundings to reduce the impact of the stressors. Confronting stress does not reduce stress—it increases it. It is like the classic paradox, “Don’t think of blue.” But what did you just think of? Blue, of course. Likewise, calling attention to stress usually just increases the stress. By changing the context, however, stress can be reduced.

In the example in Box 3.1, “wasting time at staff meetings” is the stressor. It may seem trivial, but a well-managed agenda is one of the first steps in creating emotional containment because it provides predictability and reduces stress. The conversations in this book also provide this predictive structure, allowing participants to not only manage time more efficiently but to also create space for safe explorations of ideas. Conversational processes make conversations more predictable and decrease the possibility of attacks from colleagues. Table 3.1 shows a summary of these four stressors and descriptions of the behaviors.

As you consider these descriptions, think of examples from meetings you attend regularly.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

- ■ What kinds of habits do you notice in professional conversations?

- ■ Think about ways to describe these behaviors as data and remove judgments.

- ■ Be generous in your interpretation; we all experience stress and fall back on our preferred habits.

- ■ Be mindful that when individuals exhibit these verbal responses they are responding with the emotional brain and protecting the inner self.

- ■ What evidence can you find that signals a lack of trust and shows that others are not willing to be vulnerable?

- ■ Consider what you observe as a signal to slow down, listen, and possibly inquire to discern the sources of the stress.

Adult Development Impacts the Capacity for Collective Efficacy

As we reflected upon what we learned from our own work with these Nine Conversations, we realized that how schools support adult development has great impact on this work. As we thought more deeply about our stories, we realized that when adults are stressed, they respond differently. For example, a teacher turns to a colleague and says in an unpleasant voice, “Will you just shut up and let me talk?” Later, both teachers feel bad about the altercation, and their colleagues talk behind closed doors about the “blowup at the staff meeting.” These kinds of interactions make colleagues less willing to even try to collaborate. Quite frankly, in this context teachers feel vulnerable to attack and start to avoid those with whom they do not see eye to eye.

When groups understand how stress causes adults to revert to more immature reactions, they can begin to take responsibility for their own thoughts and actions. For example, a more appropriate response to that situation would have been, “Hold on, I am feeling stressed, and I need to be able to complete my thoughts before others interrupt.” Not only does it model a clear message, but it sets a norm for respectful behavior. In our work, we have found studies on adult development to be invaluable in our understanding of how to move from stress to collective efficacy. Drawing from the adult development terms, we define collective efficacy as cultures that are able to author their own futures and continuously transform their thinking to maintain a state of collective efficacy. We celebrate when we hear, “We used to . . . but now we . . . because . . .” In real life, our friend Bondo Nyembwe (Executive Director of Academia, Cesar Chavez Charter School) told Bill, “I used to think learning was about conforming to a training model, but now I believe it is about creating a culture of high expectations, which expands repertoires to engage many different students.”

Once again, we draw the reader to the Dashboard. At the bottom center, we have listed stress as a key factor that brings down these conversations. Above stress, we offer the antidote to stress—creating contexts that allow professionals to author a future and transform their thinking as a result of this new learning. We draw these concepts from adult development as defined in the following section.

Nine Professional Conversations to Change Our Schools

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Adult Development

In the rest of this chapter, we review the thirty-five years of research by Kegan (1982), Kegan and Lahey (2009), Drago-Severson (1996, 2016), and Drago-Severson and Blum-DeStefano (2016). These thought leaders identified four distinct stages in how humans make sense of experiences, and because Drago-Severson is an educator, we use her terms here. (Note: While these terms are slightly different than Kegan’s, they describe the same phenomenon.) To this end, a person’s way of knowing shapes his or her understanding of roles, responsibilities, and capabilities at each level of development. These thought leaders suggest matching leadership interventions to the developmental level (Drago-Severson, 2004; Kegan & Lahey, 2009). While we have both used this strategy—and still fall back on it when seeking to understand individual behaviors—we have found that collective efficacy is best set through context. Through the conversations in this book, we invite professionals to both author and transform their thinking. The miracle of collective efficacy is that the whole pulls up the part—those who may have been more stuck in their thinking and are at lower stages of adult development. A friend told us a story of a teacher who reflected on how coaching had changed her interactions with her mother. The teacher described her mother’s response: “I do not know what that school is doing to you, but I sure like the way you are showing more responsibility.”

The work of Kegan, Lahey, and Drago-Severson most often focuses on individual worldviews. In contrast, our focus is on group dynamics. By drawing from this seminal work, we can articulate what we believe is a complementary view that explains how developmental mind frames limit communicative actions. We have found that when working in groups, prediagnosing individuals is not much help. In fact, our most startling discovery has been to observe how collective efficacy is value-added and becomes a virtuous cycle of improved communication for all. When groups work effectively, this behavior becomes the norm for group work and is easily adopted by newcomers. The norms do not even need to be stated, as the linguistic patterns imprint. Furthermore, working on lengthy self-help, consciousness-raising programs such as the one described by Kegan and Lahey (2009) requires excessive time and may ultimately have limited impact on group dynamics.

Understanding how these developmental stages play out in human interactions can be a great aid for working with groups and raising consciousness, which of course starts the path for change. In our experience, traditional school environments are structured to reinforce the early levels of adult development as identified by Drago-Severson (2004)—the instrumental and the socializing minds. And so we begin with a description of the status quo.

Stages I and II of Adult Development

When young adults come of age and are given adult-level responsibilities, they often rely on rules or institutional norms; indeed, in the industrial–mechanical age, rules that guided workers were the norm. Drago-Severson (2004) defined this stage as an instrumental learner. While these early stages first emerge before adulthood, we believe that when adult participants find themselves in a vicious stress cycle, they rapidly revert to an earlier developmental stage. For the instrumental learner, they seek top-down mandates and accept that a few—the appointed leaders—know better than the whole. This is a classic bureaucratic response—to attempt to mandate what matters. A teacher stuck in this mind frame might say, “I wish someone would just tell me what to do.” Schools with this top-down structure have many rugged individuals or underground guerrillas that choose to silently go their own way, creating isolated instances of excellence.

A second stage, the socializing learner (Drago-Severson, 2004), which most enter in early adolescence and adulthood, values social ties or loyalty to a group. Power and control evolves from intergroup relationships, with those not “in the group” being relegated to the fringes and often considered outliers. Teachers who demonstrate this mind frame stick with like-minded groups while rebuffing those that do not fit their norm. These schools are often considered cliquey, with “in” groups dominating the agenda and “out” groups feeling marginalized. In these schools, pools of excellence grow by happenstance and have little or no impact on the school as whole.

Adult Development Shapes School Cultures

Lambert, Zimmerman, and Gardner (2016), in their book Liberating Leadership Capacity, have defined capacity as “the ability to grow and develop as leaders through collective efforts” (note that Diane is the second author of this book). They identified four archetypal developmental stages, which map directly onto school cultural norms. The important learning here is that school cultures have the potential to both restrict and enhance adult development.

Historically, low-capacity schools describe the schools many of us attended as children, where the district office and the principal were instrumental in making important decisions and in conducting all affairs of leadership. This deference to the leader is a classic hallmark of the instrumental mind. Common in these schools are the emotional language patterns described by Satir, particularly blaming others for failures and hiding behind rationales. The next level is the fragmented school, often found in secondary schools in which departments socialize to create “in” and “out” groups to garner power and favors accordingly. In these schools, the powerful dominate, and others learn either to placate so as to stay in favor or to flee and avoid interactions. Both low-capacity and fragmented schools demonstrate a limited capacity to grow, and like the school described in Box 3.1 are stuck in cultures that reinforce more of the same behavior—a vicious cycle.

Lambert and colleagues (2016) argue that to break from old habits, all educators need to grow the capacity to lead, and indeed, that is what most school reform movements have been about. Historically, the limited-capacity school emerged with the first school reform movements in which teachers joined with appointed leaders, most often the principal, to form leadership teams. As those schools found new ways to work together, they offered leadership opportunities to those who stepped up and in some cases made significant gains in their understanding of leadership development. The problem was once again with implementation. While a few were in the know, many were still outside of the leadership circle, languishing in the knowing–doing–learning gap. Once again, mandating the intended changes by an enlightened leadership team does not work.

Lambert’s team (2016) argues that to liberate leadership capacity, schools need for everyone to take a leadership path to create the high-capacity school. This is not the traditional top-down path of directing, but rather one of cultivating knowledge, creating expertise, and passing on the gained wisdom through knowledge legacies. These schools value the time they have together as professionals and seek opportunities to meet and confer about topics of value to their own development. They are efficacious and seek challenges as a way of self-authoring a positive future.

In these schools, meetings still have a formal place; however, more often than not, teachers self-organize around different interests, and the appointed leader ends up being more like a curator of learning rather than a director. In a high-capacity school, teachers are proactive and efficacious in their belief that by working together, solutions can be authored, implemented, and articulated to create knowledge legacies.

Self-Authoring—The Critical Stage for Maturing Adults

Kegan and Lahey (2001) and Drago-Severson (2006) have written extensively about how to develop the third and fourth stages of adult development. Once again, we use educator Drago-Severson’s terms: self-authoring and self-transforming. According to her, self-authoring is taking ownership of personal authority. This is manifest through the demonstrated capacity to generate and understand values, principles, and long-term purposes despite competing needs and pressures.

Instead of looking outside for rules, or needing social relationships to validate beliefs, the self-authoring person looks both inside and outside to deal with incongruities. Probing more deeply and seeking alternative viewpoints allow the person to create an inner coherence and a more congruent identity—a person who walks her or his talk. This person is reflective and willing to modify in the face of new information or changes in the environment. At this stage, however, self-authoring individuals can still be limited by their own beliefs. And as already noted, self-authoring by an appointed leadership team can limit capacity by privileging just a few. From this worldview, these leaders are often surprised when others are not able or willing to join them and take up the authorship mantle. This points to an inner tension often seen at this stage of development. A person at this level will often wonder, “If I am willing to change my own view, why can’t they” (Kegan & Lahey, 2009)?

A word of caution: Stage development carries with it an illusion of progress and can also be thought of as fixed developmental platforms or destinations. We hold a more cyclical view of the stages. While obviously groups would want to achieve higher stages, it is important to note that even sophisticated groups find bumps in the road; when this happens, the Satir stress patterns emerge, and group behavior reverts to earlier stages of development. We believe that all the stages have the potential to be present, and it is the culture that allows the better selves to emerge, allowing for competing commitments.

Drago-Severson and her colleague Blum-DeStefano, in their book Tell Me So I Can Hear You (2016), use these stages diagnostically as part of the leadership–supervision process. They provide a guide for structured conversations in which the coach or supervisor works with that person by matching language to the developmental levels. They identify growth edges for each stage of development and honor both the present level and the potential for growth. While we do not include those conversations in our Dashboard, we want to point out that her work is a valuable contribution for coaches and supervisors, especially as they try to diagnose that critical juncture of moving from reflecting to directing. We refer those people to the books cited earlier.

The purpose of the conversations on the Professional Conversation Arc is to assist groups in learning to author a “best future.” This requires that groups interweave ideas and find common beliefs and values that support learning. This aspiration to build collective efficacy gives direction to those seeking a culture that supports self-authoring.

Self-Transforming—Finding States of Wisdom

The final stage of adult development is self-transforming. Kegan and Lahey (2009) report that the final stage of adult development, which they call interindividual, is only observed in 9 percent to 10 percent of the adult U.S. population. Drago-Severson says that self-transforming individuals show a high tolerance for ambiguity, are able to deal with uncertainty, and demonstrate a compassionate inner peace. They are patient, other affirming, and are mentors worth seeking. In Chapter 5, we provide a reflective conversation designed by Edgar Schein (2013). In our mind, Schein represents a person who appears to have become self-transforming. In his early eighties, he welcomed a chance to work with us and was as eager to learn from us as we were from him.

Coming from a mental health background, Schein’s (2013) mission was always about healing. Early in his work, he had insights about how feedback interferes with the ability to self-author. He found that help, given in the guise of feedback, is not what the person needs, wants, or even requires. Instead of giving help, he focused on the other’s actions and would query, “So what did you do?” Listening, Schein would say, is a way to learn about the other; and while the listener learns about the other, the other gets to untangle some of the problems and solutions that suddenly emerge. Schein is unflappable in his belief that we are our own best authors of learning. Thus, in helping he does not made suggestions, but keeps probing to find out about possibilities. He contrasts this with his earlier habits, which were to cut people short—to not listen or explore differences. In these later years, he talked of his humble roots and the real life issues of losing a wife and of growing old. In the end, self-transforming is not so much as about the self as a way of being in the world, which serves as a learning model for others.

Another human who has been widely sought out for his wisdom is Erich Fromm, who practiced the art of unselfish understanding—a transforming way of being. His summary of listening provides the best guide we know for seeking to be transformative. In The Art of Listening (1994), he offers his suggestions for achieving unselfish understanding:

- ■ Give complete concentration.

- ■ Free the mind of your own self-importance and personal distractions.

- ■ Stay open to imagination.

- ■ Practice empathy in a way that blurs the boundaries of self.

- ■ Reach out to the other and do not fear losing the self.

- ■ Listen for understanding, which is a gift of love to the other.

We could not have found better words to close out this first part of our book. We are where we started. Conversations that matter are within the grasp of all; we only need to personally commit to build effective habits of conversation and then use these different kinds of conversations to work collectively in order to build capacity and grow and learn as a profession. Thank you for joining us in the journey.