5 Humble Inquiry—Exploring Needs Instead of Helping

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

Be self-accountable for your own reactions and nonjudgmental about others’ reactions.

—Carol Sanford

Edgar Schein—professor emeritus from MIT Sloan School of Management— who in his pioneering role defined organizations as “cultures” and was a great mentor to us. It seems odd today, but when we both started teaching, no one talked about school culture; now forty years later, information on school culture pervades the leadership development literature. As Peter Block says in the acknowledgments of his book Flawless Consulting (2011), “All of us who consult today owe a debt of gratitude to the work of Ed Schein” (p. xxii). In the rest of this book, we refer to the agent of action as the coach, the facilitator, or the catalyst. In this chapter when describing Humble Inquiry, we use Schein’s term consultant because that is the word from which this wisdom emerged. Schein learned that just that word alone—consultant—caused problems, as others expected him to be expert and were willing to defer to his expertise. The problem is that other people’s solutions are never as efficacious as the ones we author ourselves.

As mentioned in the Introduction and in Chapter 3, we had the pleasure of working directly with Edgar Schein on two occasions. In Chapter 3, we introduced Schein as a wise human who personified the self-transforming level of development. To understand the transforming perspective, one need only to pick up Schein’s books. In Humble Inquiry (2013), his goal is to establish an ethic of inquiry in order to understand underlying assumptions and beliefs, which define the cultures we work in. He often begins his consultations with the simple question, “What do you have in mind?” In Humble Consulting (2016), he emphasizes the importance of understanding the right goals before moving to solutions. As he explains, expert consultants, in their zeal to help, offer solutions that are neither needed nor wanted and are then surprised later by limited follow-through. In Helping (2009), Schein acknowledges the importance of setting the relationship on equal footing—hence, the term Humble Inquiry.

Benefits of Humble Inquiry

Schein advocates for Humble Inquiry as a way to reduce stress and build the organizational capacity for cross-cultural teamwork. By engaging in Humble Inquiry, each person learns about the self and the other. Subsequently, with this dual understanding, the participants are better able to negotiate meanings and learn from diverse perspectives. Only by paying attention to personal reactions can one set them aside and become fully present; and only then can the diverse perspectives of the other be appreciated. “Humble Inquiry is the fine art of drawing someone out, of asking questions to which you do not already know the answer, of building a relationship based on curiosity and interest in the other person” (Schein, 2013, p. 2).

Schein argues that the Western world has a bias for task completion, and he challenges us to reexamine this emphasis. Take a moment to reflect on your own experiences. How often do participants rush through an agenda with the goal of getting it done? Schein would argue that this is the wrong goal and that task completion shortchanges thinking. Humble Inquiry opens up space for groups to explore the right kinds of questions, which also improves the quality and efficiency of the communication. Box 5.1 lists some questions to strengthen the ethic of inquiry.

In Cognitive Coaching, we have long valued the ethic of inquiry and understood the value of staying in inquiry for extended periods to generate thoughtful actions. To stress the power of inquiry, we often tell the story of Isidor Rabi, the 1944 winner of the Nobel Prize for Physics. After winning this prize, Rabi told audiences,“I don’t think I am smarter than others; I just know how to ask good questions.” He credits his mother with this habit of mind. When he came home from school each day, she would not ask the expected question—What did you learn in school today? Instead, she would ask, “Izzy, what good questions did you ask in school today?” By living in the question, Rabi went on to develop radar, which changed the course of World War II and human communication networks.

Box 5.1 Humble Inquiry—Strengthening the Ethic of Inquiry

- ■ How can I learn to listen instead of talk?

- ■ How can I ask more open-ended questions?

- ■ When can I make the time to connect with others this week?

- ■ How can I humbly inquire about what they need, want, and think?

- ■ How can I practice the behaviors of asking and listening to learn something new?

- ■ How can I practice sharing and transparency before we need it (in a crisis)?

- ■ What would they most like to tell me? What would be vital to know?

Likewise, Schein suggests extended inquiry as the essential step for first framing the problem and then finding the best solution. Schein’s conversational frameworks are best used for complex issues, in which a school may have unstated but conflicting values and beliefs. In Scenario 2 at the end of this chapter, Diane describes how she used a similar strategy to deal with a potentially contentious curriculum challenge that centered on racial prejudices.

Humble Inquiry

For the uninitiated, basic Humble Inquiry questions seem deceptively simple. Their simplicity is what makes them so powerful. To make this point, Schein (2013) tells this story. At a meeting, the participants complained that the two-hour meeting was disorganized and, as a result, was too long and substantive issues were not addressed. Schein finally asked the question, “Where did this agenda come from?” The answer? “The executive’s secretary.”

Schein then asked the secretary to join the meeting and asked her how she developed the agenda. She said she put down the items in the sequence they were given to her. She did not have the knowledge of how to prioritize. It turned out that the appointed chair had paid no attention to the priority or the time needed for different items; he simply followed her typed agenda. This chair now knew he needed to take time to organize the agenda. How many procedures endure because no one asks a question or challenges the process? Box 5.2 holds the inquiry process Schein followed.

Box 5.2 Basic Humble Inquiry—Simple but Elegant

- ■ What is going on here?

- ■ What would be the appropriate thing to do?

- ■ On whom am I dependent in order to act?

- ■ Who is dependent on me?

- ■ With whom do I need to build a relationship in order to improve communication?

Schein reminds us that humility is a lifelong goal by reflecting upon his own behavior. He often shares about a time when his daughter came to his study to ask a question, and he responded by telling her she was interrupting his work. He didn’t give his daughter a chance to explain what she wanted, and she left crying. His wife came to tell him that his daughter just wanted to know if he wanted a cup of coffee. We can probably relate to this story because we’ve have done similar things—making assumptions, not clarifying the issue, and then feeling guilty later. The moral is this: Slowing down, paying attention, and asking a simple question are such simple acts, yet they require great humbleness. On the other hand, with questions, the other responds differently. Questions are an invitation to contribute. Humble questions create a feeling that what is being discussed has not been finalized and that your contribution is useful.

Humble Inquiry is necessary if we want to build a relationship beyond rudimentary civility. The complex adaptive issues of today require a dedication to Humble Inquiry so that communication can occur across status boundaries. It is only by learning to be more humble that we can build up the mutual trust needed to work together and open up communication. These kinds of questions also begin to build knowledge coherence—an appreciation for both similarities and differences. The group gets smarter as a result of the work.

Stop Telling, Start Asking

Another barrier to Humble Inquiry is what Schein calls the “culture of TELL.” We expect our leaders to be knowledgeable, and they want to be perceived in that way. As a result, they fall back into the “telling” trap, and the culture becomes dependent on the knowledge of a few. People also quit thinking on their own because the answer will be forthcoming from the person with positional power. Knowing the answer, or certainty, is a trap that devalues the use of inquiry. Indeed, inquiry and directing behaviors are diametrically opposing concepts. As Schein reminds us, when appointed leaders are not careful, they offer help that is not desired or useful. Instead, the goal of a consultant should always be first and foremost to find out what is on the group’s mind—what are the issues they are dealing with, and what support do they need to move forward to make the situation better?

When Schein stopped telling and started asking, he discovered that most people could solve their own problems. As those he worked with gained confidence in their own skills, they were less willing to defer to the consultant. He found that beginning with inquiry served to level the playing field; now both parties were equals in seeking out the best solutions. Schein cautions that appointed leaders must continually work to create equal, reciprocal relationships. He observes that humility comes easily for those of lower status, as they often look up to a boss. When working with peers or superiors, however, it is easy to slip and take charge, forgoing humility. Humility has a palpable quality; it is felt when another engages in the simple act of paying deep attention, listening, and asking questions from a point of curiosity. Humility contributes to the subtle form of awe that emerges when we experience the joy of learning in community.

Problem-Focused Humble Inquiry

Many solutions are multifaceted and not just technical. Heifetz (1994) reminds us that complex problems need more “adaptive solutions.” The process of finding solutions is about multiplicity of options and long-term strategies rather than the one problem/one solution mindset displayed in the circus game “Whack-a-Mole.” Box 5.3 contains another simple but elegant set of questions designed to consider a problem.

Box 5.3 Problem-Focused Humble Inquiry

- ■ Tell me about what you have in mind.

- ■ Why do you want to do that?

- ■ What problem are you trying to solve?

- ■ How is what we are doing really helping?

These questions open up groups in ways often not thought possible. When groups realize they can author their own futures, the topics are endless. The key here is to introduce this problem-focused inquiry and then let groups learn how to self-organize with these open-ended questions as starting places. When Diane first became a principal, her teachers told her, “Do not schedule grade-level meetings—they are a waste of time.” Diane was puzzled, but let it go for the moment. Within the year, teachers were scheduling their own grade-level meetings; as it turned out, they were fine with grade-level meetings as long as they got to set the agenda on “what they had in mind.” In the past, grade-level meetings had been mandated with no attention to content.

What If We Are the Problem?

While asking, “What is on your mind?” often opens the conversation to topics and problems that really matter, Schein found one topic was often avoided—groups rarely reflect on their own behavior. In his humble way, Schein developed a reflection-in-action strategy to go directly to the heart of the situation. His simple question, “What is going on right now?” asks the group to look at their own behaviors in the moment. Initially, groups can struggle with this question. For example, a common dysfunctional behavior for groups is when the conversation splinters and only a few—typically three or four—are doing all the talking. This is a perfect time to ask this question and then to wait for just one person to speak up. For example, when asked, a participant might say, “I think we were done with this conversation five minutes ago.” Usually, this is enough to get others to also give their perceptions, and once this happens, others will weigh in. The focus and responsibility shift back to the entire group.

Just asking “What is happening here?” turns the question toward a reflective pause; see Box 5.4 for more ideas.

Box 5.4 Process-Oriented Humble Inquiry—A Reflection-in-Action

- ■ What is happening right now?

- ■ How is this conversation meeting, or not meeting, our mutual goals?

- ■ Anything else we should say about this?

Additional inquiries to probe further, depending upon the situation:

- ■ How is it that we are responding defensively?

- ■ Have I offended you in some way? How is that?

- ■ What should I be asking now?

- ■ Are we OK, or do we need to talk more?

This conversation does require a willingness to set aside egos and enter the Humble Inquiry arena. Once again, it is a powerful tool for transcending awkward or difficult conversations. In the end, the goal is to find out: (1) what the other is worried about, (2) what are the immediate and long-term problems that need to be addressed, and (3) what do they see as the preferred future. This process can go a long way in producing better outcomes for the individual learner and the organization as a whole.

Relationship Traps

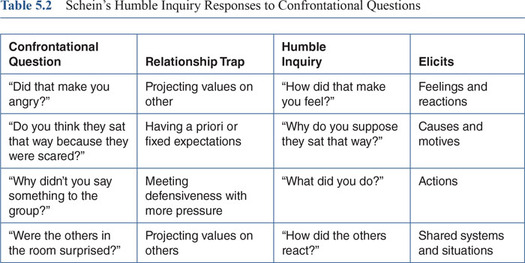

Despite a leader’s best intentions to engage in Humble Inquiry, “relationship traps” will interfere. Schein spent a career developing seven organizational principles and watching leaders struggle with their own needs for helping. Out of this learning, he developed the principles of Humble Inquiry, which are an antidote to relationship traps and are listed in Table 5.1.

All too often, it is easy to slip into a codependency. Professionals who need approval for even little actions are not secure in their own thinking and can also trap others in codependency. Diane reflects, “Initially, it feels good to help another person. But when they become dependent upon you and you realize how much time they take, you begin to try to avoid them.” Instead of codependency, the goal of Humble Inquiry is coauthoring a future that benefits all.

Humble Inquiry in Action

Humility is required for learning. Humility signals “I don’t know, but am curious to find out how or what others know.” Humble people are positive, productive team members. Think about it—if you already know everything, what’s the point of a conversation? Schein suggests that the helper’s role is to keep the process open to inquiry. Here are some other thoughts about staying in Humble Inquiry:

- ■ Slow down and ask what is on the other’s mind.

- ■ Explore the relationship to understand assumptions and beliefs.

- ■ Ask questions that require explanations and expand the information flow.

- ■ Ask for examples to clarify general statements and push thinking.

- ■ Resist the urge to jump in and provide answers.

- ■ Listen intently and frame questions from a stance of curiosity.

- ■ Stay open to questions—no one question is ever the right question.

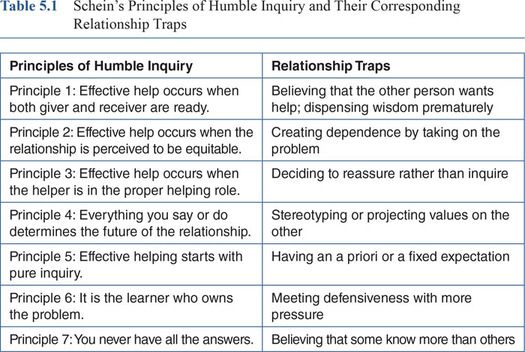

To make the point about how questions communicate different intentions, Schein (2013) contrasts confrontational questions with open-ended questions, as shown in Table 5.2. We have also added the relationship traps embedded in confrontational questions.

In conclusion, Schein is a true learning pioneer. He has created an enduring knowledge legacy. Not only did he reflect deeply on his own professional work, but he transformed his thinking as a result of this deep reflection. The insight was so profound that he spent a lifetime imparting his wisdom through his teaching and writing.

Scenario 1

A key element in Humble Inquiry is the setting aside of personal judgments in order to fully attend to and maintain equity in the relationship. This is because the act of judging splits the attention away from the other and toward internal thinking. Indeed, most humans notice intuitively when another’s intentions are no longer mutual, and the protective mechanisms described in Chapter 3 begin to set in. So in this scenario, we offer a counterexample, as it best explains both the traps that limit Humble Inquiry and the dilemmas of “helping.”

This particular example offers a key to how to use the knowledge gained within this book. All of these conversations can be mixed and matched, and Humble Inquiry is perhaps the single best strategy when we as leaders find ourselves in a relationship trap or limited by our internal judgments of the other. Any time a participant views his or her ideas as superior, it is a signal to move to Humble Inquiry.

A fourth-grade special education teacher has agreed to be coached by a team of administrators who are practicing their coaching skills. Diane had asked this teacher to volunteer, as the teacher is not only skilled but also highly reflective. As mentioned in Chapter 4, reflective practitioners are well able to talk in detail about what they know and are coming to know. They often are self-supervising. Diane thought this would be a great first immersion into coaching for these novice coaches.

The problem arose when the lead coach was not clear on his own intentions. Early on in the planning conference, it became evident he did not understand the teacher’s lesson. Instead of asking more questions (the humble path to understanding), he began judging her lesson and assumed her lesson needed fixing. He completely missed the point of the lesson and instead focused on his confusion about a complex behavior management program that used checkbooks as a reward system. Instead of clarifying his own ignorance, he shifted to judgment and assumed she needed help, which she of course did not need or want. Fortunately for the teacher, the bell rang, and it was time to teach.

To the visiting coach’s surprise, the students had no difficulty with the routines related to the checkbooks, and the teacher swiftly moved on to the lesson she had planned for the day. After the lesson in the reflection conference, the visiting coach complimented the teacher on how well the students performed the checkbook exercise. He then tried to coach her on the actual lesson, which had not been discussed previously and so limited his ability to stay nonjudgmental. This advice is reminiscent of Schein: Remember—as coaches, we don’t know what is on the other person’s mind unless we ask. We would add that as coaches—unless we engage in both planning and reflection conversations—we do not know what the teacher needs or wants in the way of help. In this example, the visiting coach’s own limitations reduced the potential of the coaching opportunity. Later when Diane checked in with the teacher, the teacher responded, “I thought it would be like your coaching—you always listen.” Diane simply apologized for the ignorance of the administrator, and the story became part of the lore about the arrogance of some administrators.

Scenario 2

Diane reflects on a process she put teachers through years ago, well before she could call it Humble Inquiry. An African American parent had challenged a sixth-grade anchor text in which an Afro-Caribbean man saves a shipwrecked Caucasian boy. From the Caucasian perspective, it is a story of redemption in that the boy transcends his prejudice and loves his black savior. The boy’s character is the central theme of the book and is well developed. The African Caribbean man is portrayed as a grizzled, one-dimensional man who is only focused on helping the boy. The complaint from the parent centered on the lack of character development of the minority person. Not only was the character of this man devalued and narrow, but his patronizing way was a weak role model for her own daughter—the lone African American student in this predominately Caucasian school.

Diane knew that for teachers these book choices were sacred and that any challenge to these choices were often greeted by emotional, defensive behaviors. This challenge was even more problematic because of the overlay of the racial tensions and a mandate from the superintendent that the school address questions raised by the minority community directly. Diane was working on her PhD at the time and realized that this was a great opportunity to conduct a microaction research project on how literature themes impact students; however, before starting on this journey with her teachers, Diane decided to engage in the ethic of inquiry to help develop a productive path for studying the issues.

Diane started the discussion with her teachers with two open ended-questions that focused on the existing belief systems: (1) What do we know about this book? and (2) How does our Caucasian perspective shape our knowing? It turns out the teachers loved to read this book with their sixth graders because they thought it transcended racism.

Diane then asked, “What do we know about how this book shapes the African American perspective?” This question stopped the group cold. They realized the only information they had was from the student’s mother, so they asked to see her letter again. This was the breakthrough. The student’s teacher became particularly vocal in support of the student viewpoint after considering the mother’s words: “My sixth-grade daughter is extremely shy and, as the only African American student in the classroom, does not feel comfortable speaking up about her own viewpoints.” The teachers were fascinated and wanted to know more. This opened the door for the action research project that focused on the colonizing themes found in this and other books used as anchor texts.

While this example did not draw from Schein’s Humble Inquiry (the book had not yet been written), the example describes how powerfully a humble approach can open doors for robust conversations about sensitive ideas, values, and beliefs. The interesting thing for Diane was that once the teachers had this discussion, the debate was gone. Not one teacher was in favor of using this book as an anchor text in the future. Diane says,

As I look back on this, the words of Schein ring true. If I had taken another path, the teachers would have focused on their problem, which was who controls the curriculum, and completely missed the opportunity to learn from this parent. The problem was elegantly framed by the mother, but without taking time to thoughtfully consider her insights, we would have solved the wrong problem.

As we look back over our careers, we wonder how many other times we hid behind policies in an attempt to solve our problem and didn’t listen to the stakeholders.

A Final Note—The Quick Intervention

Here, we offer an example of how Humble Inquiry can be used in the moment to shift the work of a group toward more productive ends. Working in the district office required Bill to sit through many a meeting that spent too much time on the “killer Bs”: budgets, buses, and boundaries. At an appropriate time in a meeting, Bill reflected, “What is going on here? I am wondering what is really on our minds, what really matters to us.” It was as if a dam broke, and everyone started talking about the real issues of educating students, particularly students who were not thriving. Looking at the district mission posted on the wall, Bill again wondered, “What is going on here? How have we forgotten our mission that focuses on student learning?” He was met with silence. Then he asked, “What do we really want to spend time in meetings doing?” Answers were not forthcoming, and time was up. But the gift was that these questions caused the key leader to reflect on his agendas and to set aside quality time to talk about learning and teaching.