9 Positive Deviance—Mining for Group Gold

Urban Luck Design, urbanluckdesign.com

It’s easy to come up with new ideas; the hard part is letting go of what worked for you two years ago, but will soon be out-of-date.

—Roger von Oech

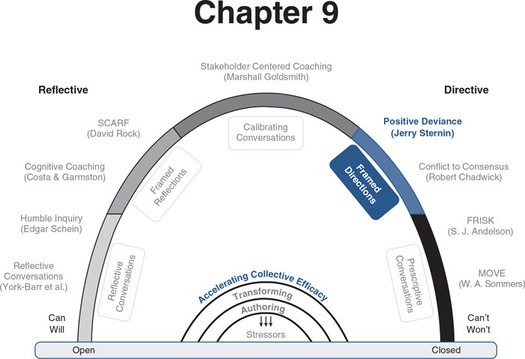

As we transition from Stakeholder Centered Coaching, the Positive Deviance process asks more defining questions, relies on more specific data, and includes a wider focus than just individual skills. The power of Positive Deviance (Sternin & Choo, 2000) is that through rigorous investigation it identifies pockets of success that inform new ways of solving persistent problems. This model, with its exploration into the unknown, expands the knowledge base and positively affects the learning health of organizations. When done well, it creates a virtuous cycle of success, which delves more deeply into the nuances of what works. Positive Deviance, at its core, designs intervention strategies that are scalable and efficacious. As groups learn to interrogate reality and find new solutions, they learn to use this strategy whenever they are stuck or hit an apparent dead end.

By drawing from the internal resources of the community, the changes are more acceptable and accessible, increasing the group commitment to implementing new solutions. Bill wishes he had understood this process earlier in his career. In his zeal to help, he would often send his teachers examples of outlier ideas—those ideas he thought would make a difference. He had the belief that if everyone knew current information, staff would immediately use it. As he was writing this, he laughed, “Ha! What Kool-Aid did I drink?” Diane responded, “The same one all naïve leaders drink. The one that made us believe that if we shared the right information it would bring change.” In contrast, Jerry Sternin (1991), developer of the Positive Deviance model, and his colleagues did not send out information, did not make posters and post them around the community, and did not make a report to the officials and leave. Instead, they studied the community and looked for pockets of success—or positive deviants. This enabled them to teach about the intended changes from the inside, using neighbors to teach neighbors.

Positive Deviance is asset-based rather than deficit-based and is grounded on the observation that in every community there are some who exhibit uncommon behaviors and have better solutions to problems. In a now-classic case, Sternin (1991) describes how he created a government-sponsored program to save young Vietnamese children from malnutrition. He asked the local communities to identify families that were not malnourished. These families were the “positive deviants.” They were positive because they seemed to be doing something successful and deviant because their practices were outside of the norm. It turns out that some of the mothers collected tiny shrimps and crabs from the rice paddies, providing just enough protein to improve their children’s diet. Others in the community believed that this food source was not good for their children, so lacking sufficient protein, their children were malnourished. Using this information about how to introduce protein into the diet, the aid workers could now build a sustainable program based on best practices right out of that community.

Jerry Sternin is another of those humble people that we turned to over and over to write this book. His work in Vietnam certainly gives a glimpse of Jerry as a human being and his commitment to social justice. A few of the other projects he worked to solve were female circumcision in the Middle East, getting special services for people in Appalachia, and various Peace Corps projects.

Jerry also worked with the Children’s Aid Society in the Bronx in New York City to focus on the black and Latino males who were not succeeding in school. He firmly believed that increasing their success rate would lead to better citizenship, relationships, and community. They rigorously studied these adolescents’ relationship with four core concepts—respect, relationships (dating and family), time management, and school activities. They searched for positive deviants in each of these core areas. In the successful students, they found high values of respect for themselves and other students—habits such as sitting toward the front of the class and family commitment to eating meals together and reviewing homework. Many of the success factors seemed basic, but they made a difference for these young men. They also found that students who were invited to do errands for the family also did better. While each one of these might not make a difference alone, it should be clear to the reader that parents whose homes have all these values raise their children in a different cultural system than those that do not.

Mining Group Knowledge—Finding Success From Within

We have found that seeking what is working, looking for what is called positive deviance, can be a valuable professional development activity with the possibility of adding repertoire and creating knowledge coherence. Over the years, we both noted that there were teachers who had developed little tricks of the trade that made huge differences for classroom management. A few of the things Diane learned from other teachers were so obvious, yet they saved her from hours of tedious work. As a new teacher, she spent far too much time cleaning up after her primary-aged children and making answer sheets to correct math work. She learned simple but elegant solutions from other teachers. For cleanup, she observed how a kindergarten teacher required that any toy, especially the puzzles, could only be taken apart in an aluminum tray. If the child could not put it together, which was often the case, he or she returned it to the shelf. Another child would always come along and finish it up. Another trick was instead of taking valuable time to make an answer key, she instead could compare two student papers and only work out the problems that did not match. In this way, a student paper became her answer key. Instead of having to calculate an entire sheet, she would only have to calculate one or two divergent answers. While simple, these two small changes allowed Diane to spend valuable time on learning plans instead of maintenance.

The point is this: Schools are resource rich and steeped in tacit knowledge. Yet teachers rarely share these tricks of the trade. Positive Deviance is an approach to social change that seeks out individuals, practitioners, and outliers in the school and community that model desirable behaviors. But the practice of seeking positive deviance is the act of seeking out outliers. Many times in schools, there are remarkable teachers doing great things for kids, and very few know about it. We are a humble bunch who don’t want to come across as arrogant. In our experience, schools rarely look for positive deviant behavior. This means that valuable knowledge legacies are left untapped.

Teachers will often know that a teacher is successful, but rarely ever inquire as to why. Diane tells the story of a sixth-grade teacher known for teaching writing, who at retirement shared his binder full of student writing samples. Long before it became a standard practice, this teacher had figured out that well-written student samples provided attainable models for his students. It was only in retirement that the school community learned about his binder full of the best student writing. Diane laments, “If we had only looked into his success, we would have all benefited. Here we had an example of Positive Deviance in our school—a teacher who was successful—and we never thought to ask him how he did it.”

This failure to notice continues to be one of Diane’s regrets from her years as a principal. One cannot but wonder about all the untapped and unappreciated knowledge that accumulates in teachers’ behavioral repertoire but never gets shared.

Applying Positive Deviance in Our Schools

Bill tells how Jerry Sternin and his wife Monique described their success to the board of directors for the National Staff Development Council (now Learning Forward). With a short time frame of six months, Jerry told us that he could not rely on preconceived questions, statements, directions, or information to find solutions. He knew he needed to immerse himself in the community in order to listen and observe very carefully and rigorously inquire about the few successes. By asking about the kids who were not starving and what their parents were doing differently, Jerry was able to identify positively deviant behaviors.

Positive Deviance is a model to find out what is working inside the system but has not been implemented systemwide. Not only do we want to find out what works for our kids, our parents, and our community, but we need to use this knowledge to build a more coherent knowledge base that can be passed on to newcomers. A leader can facilitate a mind shift from “OMG, more data, more guilt, and more time wasted!” to “We can learn from data that show deviance and better results.” This shift focuses on how we know something is working and generates more interest and energy for finding new ways to improve learning for students.

Define–Determine–Discover–Design–Discern–Disseminate

The Positive Deviance process (see Box 9.1), developed by Sternin and associates, is outlined with the six Ds that are used to analyze a defined problem. Jerry’s story, which follows, also helps to define the process.

Box 9.1 Positive Deviance Process Ds

- ■ Define: What are the problems? Solutions? Desired outcomes?

- ■ Determine: Where can we find examples of desired outcomes?

- ■ Discover: What are the unique practices of those who are successful?

- ■ Design: How can we design and implement an intervention?

- ■ Discern: How will we know if it is effective?

- ■ Disseminate: How can we make this knowledge (practice) accessible and scale up?

- ■ Define: What are the perceived causes? Solutions? Desired outcomes? Jerry asked, “Are there healthy kids in this community where many are starving?” The standard process had been to only look at the starving kids, not the healthy kids. But basically, Jerry was defining and reframing the problem.

- ■ Determine: Where can we find examples of desired outcomes? Jerry wanted to find children that were healthy who were living in the same community as starving kids. He started collecting information on the healthy kids. He also wanted to make sure that the healthy kids did not have outside resources that other kids would not have access to—for instance, an uncle who was a pharmacist in a neighboring town.

- ■ Discover: What are the unique practices of those who are successful? Once healthy children were identified, Jerry proceeded to find out what the families were doing that helped their children be healthy. He made a list of practices that parents and communities were using that produced healthier kids.

- ■ Design: How can we design and implement an intervention? Teams went out to compare and contrast the two populations. They carefully studied the practices of both groups in order to design an implementation plan.

- ■ Discern: How will we know if it is effective? In this case, the changes were observable. The successful parents fed their children four times a day instead of twice a day like the less healthy kids. The parents of healthy kids were feeding them small shrimps and crabs available in the fields; this was protein. These seemingly small differences in a couple of behaviors led to healthier kids.

- ■ Disseminate: How can we make this knowledge (practice) accessible and scale up? To introduce the new plan, Jerry and the team convened community conversations between parents of the healthy children and parents of the unhealthy children. They each shared what was working and what was not working and talked about what they noticed when their children were thriving.

Reflection

A Place to Pause

iStock.com/BlackJack3D

Think about your own experiences:

- ■ Who could be positive deviants within the system?

- ■ How could you find out more about them?

- ■ How could their knowledge add to the legacy of the school?

- ■ What insights can you gain from working with those whom you do not know well?

Data-Driven Discussions—Taking the Path of Positive Deviance

In Chapter 1, we described a crisis in our midst. Of all the strategies offered in this book, we consider Positive Deviance to be the most important strategy for addressing this crisis based on current practices. Quite simply, our schools continue to look at what is wrong, not what is right, and the test scores trap practitioners in vicious counterproductive conversations. As the mandates have shifted to the need to examine data, the assumption has been that this will inform instruction. The reality is that analysis of test scores tells us nothing without looking for the behaviors that support the evidence. Actually, using the right kind of data and asking provocative questions are what is needed. We have lots of data, which alone doesn’t tell us much. Frank and Magnone (2011, p. 207), in their book Drinking From a Fire Hose, say, “Data is a means to an end. It is the supporting character. Too often, it takes center stage.” Positive Deviance conversations provide ways to use the data to seek out real practices that make a difference for students.

Bill has effectively used this process to shift teachers toward solutions when analyzing test scores. He realized when he had all his teachers together, it was a prime time to seek out examples of Positive Deviance. Table 9.1 has questions that helped focus the conversation and bridge the gap of data to practice.

Bill wishes he had used these questions years ago while working with a group of high school English and reading teachers. He could see the staff was not as successful as they could be, and meetings were consumed by looking at data. When he looks back, he knows he could have shifted these conversations by using these strategies he developed later. Diane laments the years spent studying language arts data sets with elementary teachers. “More often, year after year, we concluded the same thing—that ‘inference’ was a critical skill.” Another school spent hours working on a benchmark assessment for fractions. As one teacher put it, “We always ran out of time and never talked about how to help those students who just did not see fractions.”

When we look, we find examples everywhere. High schools will often find that they have an attendance problem and yet never dig down into the data to find out what success with this same population looks like.

As we wrote this chapter, we realized that Positive Deviance is a powerful way to take teachers away from the numbers and toward seeking examples of positive behaviors that change practices. Instead of developing benchmark assessments, which just generate more data, this process breaks down the abstractions and generalizations gleaned from the data and begins to map them to real teaching and learning in schools. When humans learn to appreciate differences, they seek them out and persist in finding others that have the solution. In short, the culture begins to seek out differences and celebrate unique approaches for a myriad of challenges that teachers face daily. Furthermore, now, with the advent of the Internet, learning from deviance is much easier. Blogs, help services, and short videos are available to teach just about anything.

Knowing How We Make a Difference—Positive Deviance Is Efficacy in Action

We consider seeking positive deviance a moral imperative for your schools. It is not acceptable to continue to ignore the years of tacit knowledge gleaned by teachers in a career working with children. It is a travesty that this knowledge is left unspoken. Even worse, the longer teachers are in a profession that does not support personal growth and development, the more likely they are to remain silent.

Wisdom comes from learning what we do not know; collective wisdom builds efficacy. When we think of positive deviants, they are highly efficacious individuals. People who believe they can have a positive influence on results, in fact, do. If they can’t, they find a way to do it anyway. Finding the positive deviants, supporting them, and creating conversations that expand their influence increase collective efficacy in the system. The research by Tschannen-Moran (2004) and Hattie (2012) shows a definite correlation between collective teacher efficacy and student learning.

In addition, research on teaming by Edmondson (2012) supports that learning from each other as peers increases the exchange of ideas and promotes learning. Bryk and Schneider (2002), in their seminal work on trust, show that increasing trust among teachers has the most significant effect on student learning. When teachers learn from others, they change the way they interact and build knowledge coherence. Knowledge legacies become a way of life.

John Merrow (2015) reports that 80 percent to 90 percent of teachers go into the profession because they want to make a difference. As leaders, we want to promote learning that produces results and increases teacher efficacy. Not only is it the antidote to burnout; it also fosters high performance in students. Our belief that elevating teacher efficacy drives student achievement is important.

Bill smiles when he thinks of a conversation he had with Jerry Sternin at the board of trustees’ meeting of NSDC/Learning Forward. Bill said, “Jerry, you are smart. Why didn’t you just tell the officials what to do?” Jerry’s answer was, “Do you think the people in Hanoi would believe two white people from Boston?” Point taken.

The fact is that we will listen to people who are working in the same school with the same kids rather than put stock in an outside expert to find THE answer. We certainly can learn from other schools/districts, which can provide possibilities, but in the end, we have to do the work in our school. Let’s make sure we mine the minds of our own experts and look for group gold while we search for additional models that may help our kids.

Scenario 1

This example would probably surprise Sternin, yet he would agree with it. Not only does Positive Deviance look to the outside, but it can also be used as a personal reflection tool. When humans get caught up in the stress of the moment, they forget what success looks like. They deviate away from practices that renewed their teaching and student learning. They start to experience burnout. In almost all cases of burnout, they have deviated from the positive.

As an antidote to burnout, teachers benefit from searching their own success stories for examples of positive deviance—something they did in the past but for some reason abandoned. This question opens doors for teachers to seek out their own deviations from the positive: “At what times in the past have you enjoyed the most success with students?” One teacher realized that art brought joy into her classroom and decided that every week the class would complete at least one art project. Another taught Guitars in the Classroom and was thrilled with the warmth that his kids showed toward him and others during their sing-alongs. Another teacher had spent hours as a child making miniature scenes and decided that doing this same thing with his students would be a way to make some of his history units more interesting.

At another time, one teacher publicly stated her current group was the worst class she had ever taught. Later that day, her principal invited her for a check-in. As they talked about her class, the principal asked, “So tell me about your favorite class ever. What happened that year that made you enjoy teaching?” This was a variation of the deviance question. The teacher was hesitant, but as she got deeper into the story, she realized that in the past she hadn’t felt so pressured to get the textbook done (pacing guides had been mandated in the past two years). In prior years, she found time every day to do something that brought joy to her and her students, but somewhere along the way, she had abandoned this practice. Her principal gave her permission to reinstate this practice, even if the students did not finish the textbook. The teacher finished the year loving those children.

In another example, a teacher was shocked to learn that a parent had requested a transfer for her child after the first day of fourth grade. The child had come home complaining about how boring school was. Upon reflection, the teacher realized that the first day had indeed been boring; she had spent almost all their time on rules and routines. She shifted gears and pulled out a few of her favorite lessons, and by the end of the week, the student was happily settled into fourth grade. These tiny changes are like the bits of fish that the Vietnamese mothers gave their children—microscopic, tiny, seemingly unimportant details that are transformative in their power.

Scenario 2

Diane and her staff decided that they would take every minute they could from staff meetings to analyze student writing samples to give every teacher a chance to study writing from every grade level. Despite some grumbling from a sixth-grade teacher about looking at kindergarten writing, the staff prevailed, and he went along. They found a surprise when they hit fourth grade. Up until that time, a clear progression was noted each year as kids got better at handwriting, spelling, grammar, and their ability to put words on paper. Then they looked at the intermediate writing. Two fourth-grade classes stood apart; otherwise, there was not much distinction between Grades 4, 5, and 6. In every classroom, a few students were successful writers, but many seemed to have plateaued.

The teachers worked in grade-level teams to find answers to the question “What are the examples of success for high-performing students in each class?” The fifth- and sixth-grade teachers came to roughly the same conclusion. In each of their classrooms, about 30 percent of the students seemed to know how to write, but the rest did not. What they noted, with disappointment, was that unlike the primary writing, there was no clear developmental distinction from fourth to sixth grade. They were discouraged.

But one data set stood out—it was a positive deviant. Two fourth-grade teachers had more above-average writing samples than any of the other intermediate teachers. In the three fourth-grade classrooms, one class had a similar profile to the rest of the school—about 30 percent of the students were at grade level or above, and the rest were not. (Notable in all of the below-standard samples was a lack of complex thought.) However, the other two fourth-grade classes had 50 percent and 60 percent of the students above average.

As they talked with these two teachers about the “unique practices” that were getting the results, they discovered their answer. First, both these teachers had received advanced training in the writing process while none of the other teachers had. Second, when collecting the samples, the staff had decided that each teacher should do the setup they normally used when collecting a writing sample and assumed this would level the playing field. It turned out that this explained the deviance. These two teachers had engaged the students in their normal prewriting exercises. These teachers discussed the topic and made a visual map of what the students knew, listing words that might be difficult to spell. With the students, they generated a list of questions to get them interested in the topic. In these two fourth-grade classrooms, these teachers had learned to build in success factors before the students even started writing. Armed with the prewriting prompts, the students wrote more paragraphs with more complex thought and fewer errors in spelling. What is amazing is that Positive Deviance speaks for itself. All of the intermediate teachers wanted to receive the same advanced training as their fourth-grade peers.