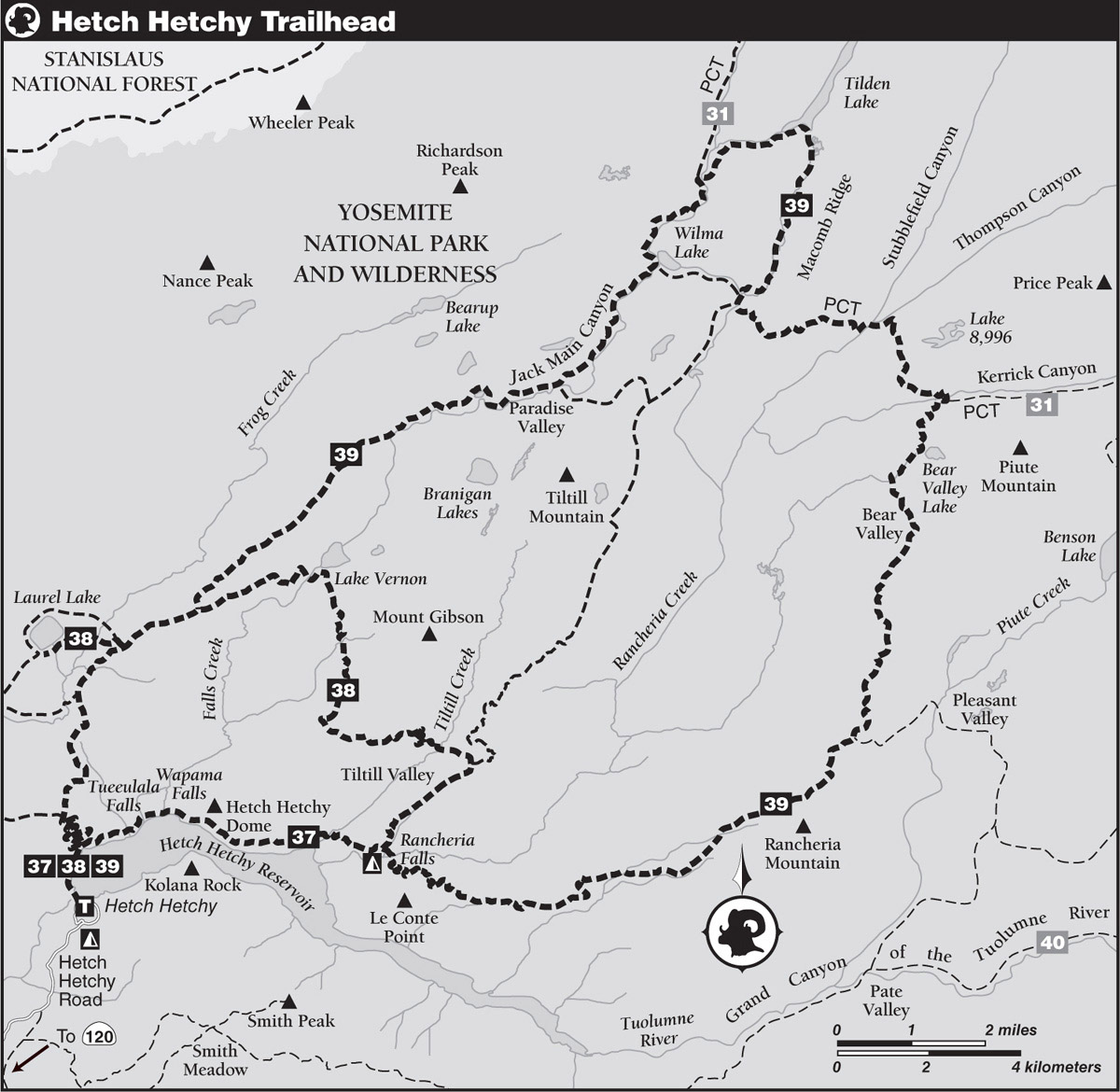

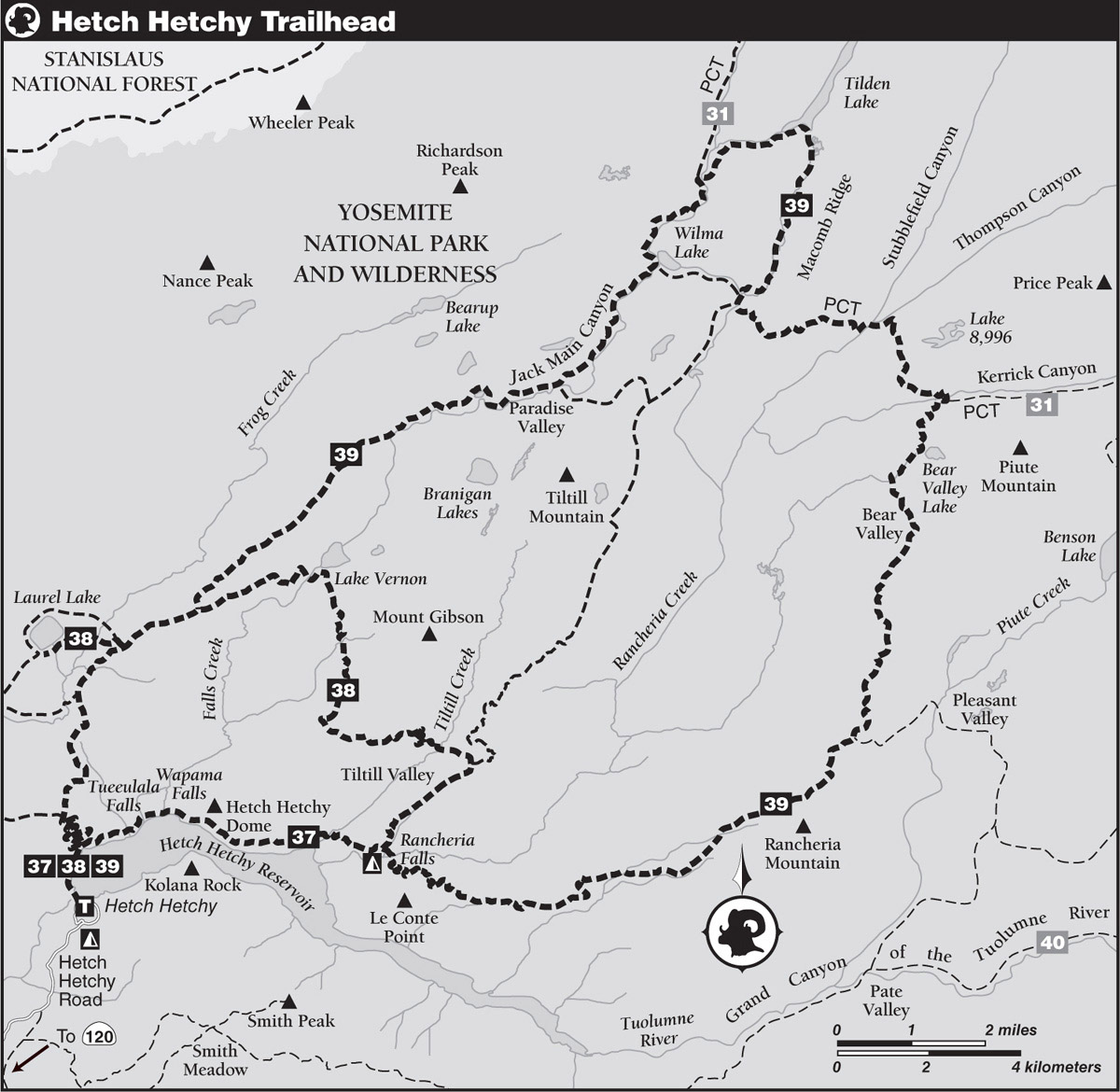

INFORMATION AND PERMITS: These trips are in Yosemite National Park: wilderness permits and bear canisters are required; pets and firearms are prohibited. Quotas apply, with 60% of permits reservable online up to 24 weeks in advance and 40% available first-come, first-served starting at 11 a.m. the day before your trip’s start date. Permits for Hetch Hetchy are best picked up at the Hetch Hetchy Entrance Station/Mather Ranger Station where you enter the park. Fires are prohibited above 9,600 feet. See nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm for more details.

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From CA 120 (Tioga Road), turn left onto Evergreen Road, located just 0.6 mile west of Yosemite National Park’s Big Oak Flat Entrance Station. Drive 7.4 miles north on Evergreen Road to its junction with Hetch Hetchy Road, an intersection located in the middle of the small community of Camp Mather. Turn right, drive beneath an archway, and continue 1.3 miles to the Hetch Hetchy Entrance Station/Mather Ranger Station.

Road use is restricted beyond this point. In midsummer the road is open 7 a.m.–8 p.m., but open hours decrease with dwindling daylight hours. The current hours are posted where you turn onto Evergreen Road or on the Yosemite National Park website; just search for “Hetch Hetchy open hours.” At the entrance, your license plate is registered, and you are given a placard to display on your dash. Once past this bottleneck, drive 7.1 miles to a junction branching left for the Hetch Hetchy Backpackers’ Campground. Backpackers must park in the obvious parking area by the road’s start, then walk 0.5 mile on the road to O’Shaughnessy Dam. Backpackers can stay at the trailhead backpackers’ campground for a night before and/or after their trip.

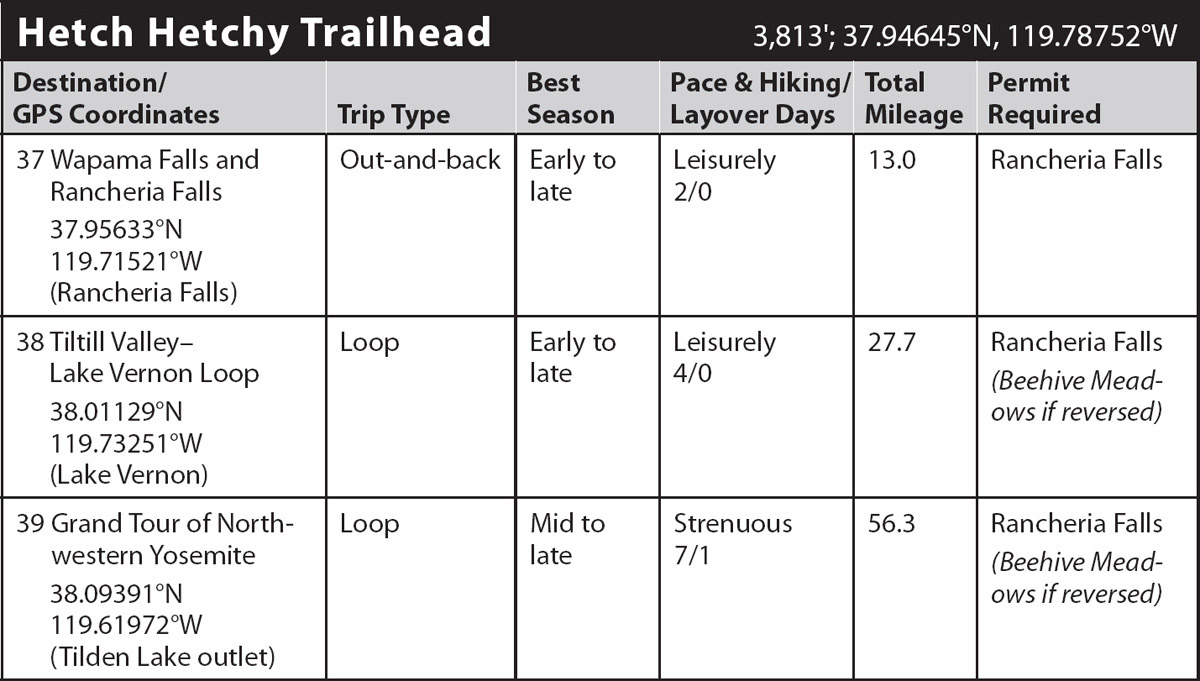

trip 37 Wapama Falls and Rancheria Falls

Trip Data: |

37.95633°N, 119.71521°W; 13.0 miles; 2/0 days |

Topos: |

Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Lake Eleanor |

HIGHLIGHTS: This walk is the perfect choice for an early- or late-season ramble, accessible most times the road isn’t snowed in. Wapama Falls is stupendous in spring, and beautiful 25-foot Rancheria Falls tumbles into large, inviting pools—a wonderful destination. Note: the park closes the Wapama Falls bridge under extreme run-off conditions.

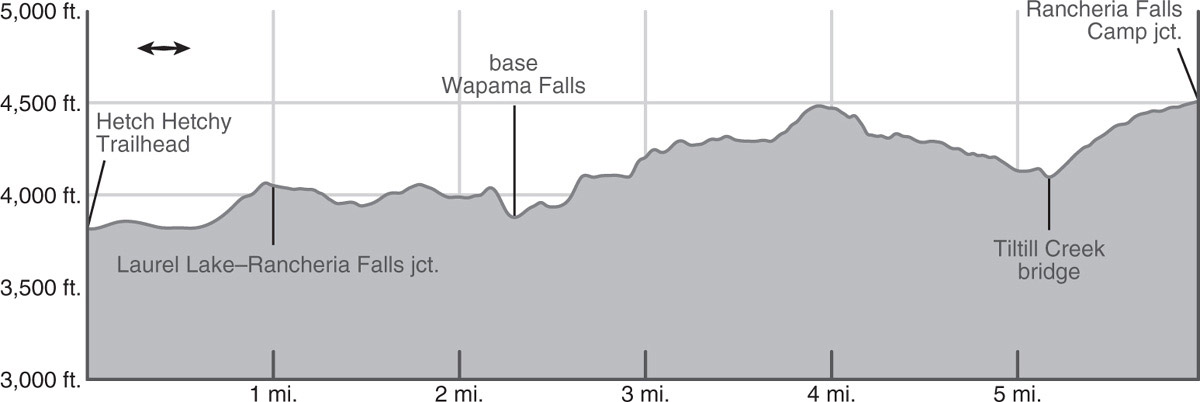

DAY 1 (Hetch Hetchy Trailhead to Rancheria Creek, 6.5 miles): From the trailhead, cross 600-foot-long O’Shaughnessy Dam (3,813'), enjoying views across the water to, from the left (north), seasonal Tueeulala (twee-LAH-lah) Falls, Wapama Falls, Hetch Hetchy Dome, and Kolana Rock. Beyond, you immediately plunge into a quarter-mile-long tunnel.

Exiting, your trail is a badly deteriorated service road that once led to Lake Eleanor. The road winds along the hillside just above Hetch Hetchy’s high-water mark through scattered canyon live oak, incense cedar, Douglas-fir, California bay, and big leaf maple, some sections burned in the 2013 Rim Fire. Watch out for poison oak here. Soon after the road begins a gentle ascent it reaches a junction, where you turn right (south, then east) onto the trail signed to Rancheria Creek, while the left (east, then north) fork climbs toward Laurel Lake.

The occasional airy gray pine and live oak provide little shade, as the trail winds along a sunny bench. Glacial polish and glacial erratics, boulders transported and then dropped by the glacier, remind you that at times during the Pleistocene Epoch glaciers flowed down this canyon. You descend the slabs gently, first south, then east, across an exfoliating granitic nose, then switchback once down to a broad sloping ledge, sparingly shaded by the grayish-green foliage of gray pine. From April to June this area is often decorated with an assortment of wildflowers, for the granite slabs are impervious and water pools atop them, creating miniature vernal wetlands. Follow these ledges 0.5 mile to a minor stream that, until about early summer, spills down the wall above you as ephemeral Hetch Hetchy Falls (an informal name, and incorrectly marked as Tueeulala Falls on many maps—keep reading).

Beyond it you continue across slabs on the north shore of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir to a bridge over a steep, generally dry cleft, followed almost immediately by a seasonally wet boulder crossing over the outflow from the waterfall that is actually Tueeulala Falls; it lies 0.2 mile east of where it is marked on most maps. Depending on the time of year, seasonal Tueeulala Falls either spills forcefully down a near-vertical wall or is absent because it is created by a seasonal overflow channel from Falls Creek, the creek whose main channel is Wapama Falls’ source.

You next descend some 100 feet of granite stairs through a field of huge talus blocks. If you’re passing this way in early summer, flecks of spray dampen your path as you approach the five bridges spanning Falls Creek at the base of Wapama Falls. Check with the park service before hiking here; in spring and early summer, vast, crashing, tumultuous Wapama Falls will cover these bridges with spray and even flowing water and at times they are deemed sufficiently hazardous to be closed by the park service.

Just past Falls Creek, the trail exits the dense fly-infested live oak forest onto a boulder slope—here a large rockslide in the spring of 2014 decimated the forest and trail. Beyond, the trail winds in and out of forest cover as it traverses the base of Hetch Hetchy Dome on a series of benches, eventually emerging onto a meadowy ledge system where you have an airy view of the water below. In spring, wildflowers such as monkeyflower, paintbrush, and Sierra onion color the ground.

Past the ledges, the trail makes a long descent, crossing Tiltill Creek on a bridge, from which you gaze upon the creek tumbling down its gorge 60 feet below you. The trail next climbs onto the low ridge separating Tiltill Creek and Rancheria Creek, traversing it to reach a shaded flat 0.8 mile beyond the bridge. Here is an unmarked junction with a spur trail leading right (south) to the Rancheria Falls streamside camp (4,515'; 37.95633°N, 119.71521°W; 6.0 miles from trailhead; elevation profile to here). Rancheria Falls, some quarter mile upstream, drops 25 feet into deep, swirling pools. Fishing in Rancheria Creek can be good for rainbow trout.

Wapama Falls Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

You’ll note the trip’s mileage indicates you have another 0.5 mile to hike, and indeed, after depositing your belongings at camp, I urge you to continue up to a bridge spanning Rancheria Creek: in spring, watching the water plummet past it is mesmerizing and, at low flows, descending below the bridge yields additional swimming holes. To reach it, continue up the main trail, turning right (south) toward Rancheria Mountain at a junction, where the left (north) fork leads to Tiltill Valley, and soon thereafter reaching the bridge spanning Rancheria Creek.

DAY 2 (Rancheria Creek to Hetch Hetchy Trailhead, 6.5 miles): Retrace your steps.

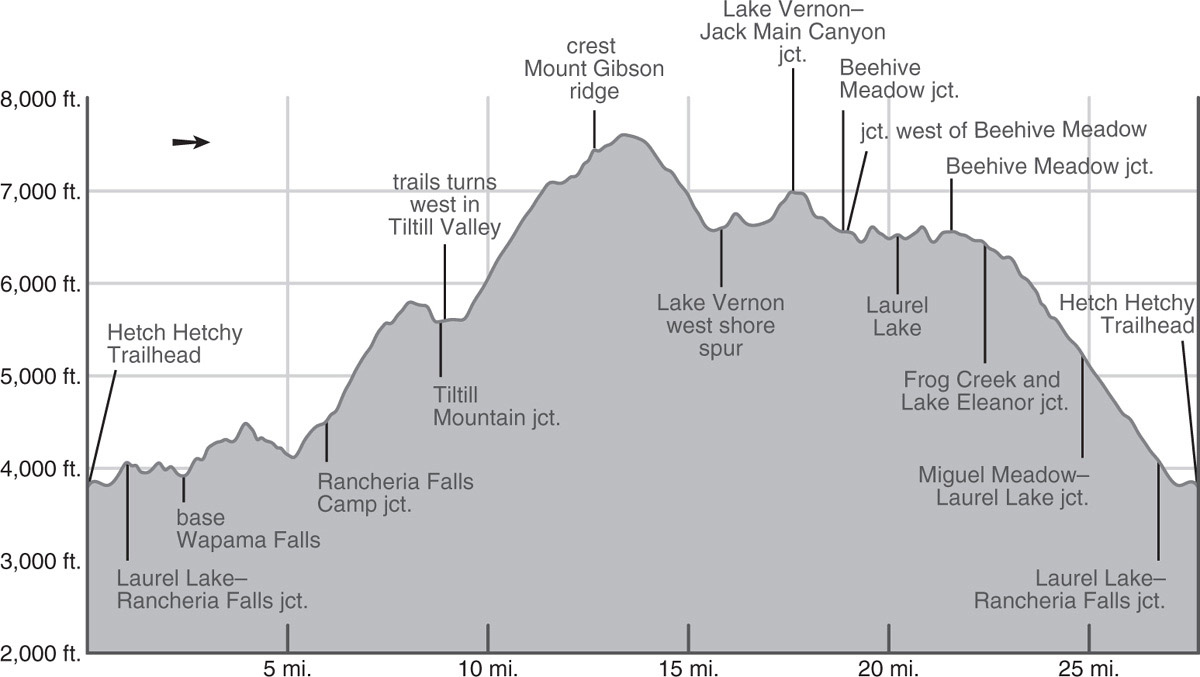

trip 38 Tiltill Valley–Lake Vernon Loop

Trip Data: |

38.01129°N, 119.73251°W (Lake Vernon); 27.7 miles; 4/0 days |

Topos: |

Lake Eleanor, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Tiltill Mountain, Kibbie Lake |

HIGHLIGHTS: This loop hike is a perfect spring conditioner when higher elevations are still snow covered. It tours the majestic waterfalls and granite cliffs defining Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and visits two nearby low-elevation lakes, Lake Vernon and Laurel Lake.

DAY 1 (Hetch Hetchy Trailhead to Rancheria Creek, 6.0 miles): Follow Trip 37, Day 1 to the Rancheria Falls streamside camp (4,515'; 37.95633°N, 119.71521°W).

DAY 2 (Rancheria Creek to Lake Vernon, 9.8 miles): Return to the junction with the main trail, turn right (north) and begin climbing, soon reaching the next junction, where you follow the left-hand trail west to Tiltill Valley, while right (east) leads up Rancheria Mountain and to distant destinations, including Bear Valley (Trip 39). The trail to Tiltill Valley switchbacks 1,200 feet up a burned, dry, exposed slope well loved by rattlesnakes, to reach a timber-bottomed saddle and a small tarn brimming with yellow water lilies in spring. As the trail descends north off the saddle, it traverses a pine forest with a sprinkling of incense cedar and black oak.

This duff trail emerges toward the east end of Tiltill Valley, a long meadow that, in spring and early summer, is usually quite wet and boggy. The trail dives due north across it—either through water or tall grass. Despite a series of levies elevating the trail tread, your feet may well be wet before you reach a deeper ford of a Tiltill Creek tributary. Just beyond the tributary ford is a junction where continuing straight north across the meadow leads to Lake Vernon (your route), while a right-hand turn (east) traverses the rest of the meadow, then ascends the ridge radiating off Tiltill Mountain, ultimately leading to the Pacific Crest Trail.

Once on the north side of Tiltill Meadow, curve left (west) and traipse beneath lodgepole pine cover, winding between some massive boulders and finding excellent campsites to either side of the Tiltill Creek ford (5,595'; 37.97611°N, 119.69778°W). These camping places, located in isolated stands of lodgepole and sugar pines, afford campers uninterrupted vantage points from which to watch wildlife in the meadow. Fishing for rainbow trout in Tiltill Creek is excellent in early season.

While some hikers will split Day 2 in half, completing just the 3.4 miles to Tiltill Creek for the day, most will continue onto Lake Vernon, next ascending 1,400 feet up well-built switchbacks that climb northwest out of the Tiltill Creek drainage. Spring flowers are showy, as the trail alternates between tree-covered and brushier slopes, transitioning entirely to shrubs by the time the trail assumes a more westward trajectory, skirting around a ridge emanating from Mount Gibson. Here the whitethorn, together with companion shrubs like chokecherry and huckleberry oak, rapidly choke the trail between prunings—the aftermath of fires in 1960 and 2004—and can make for a scratchy walk. If the trail crew has been through recently, you barely notice the shrubs and delight in the views and the colorful wildflower displays; especially noteworthy here are the forget-me-nots.

The trail now arcs northeast to the crest of a lateral moraine, which, from our vantage point, is only a low ridge, though it stands a full 4,000 feet above the inundated floor of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River. The glacier that left this moraine was therefore at least that thick. At 3.3 trail miles beyond Tiltill Valley, the gradient eases, and you begin a long, more forested traverse across the massive west flank of Mount Gibson, passing some delightful meadows and aspen glades and crossing minor ridges that are additional moraines. Another prominent moraine crest marks the start of the switchbacking descent, and after a drop of about 350 feet you suddenly transition from rubbly glacial deposits to smooth expanses of granite—indeed there are now granite slabs for as far as you can see. You follow three dozen switchbacks diligently down to the south shore of Lake Vernon, where the trail curves west toward the lake’s outlet.

Camping options around the lake are varied. Those in search of a sandy home among slabs should search the lands south and west of the lake, while those wishing for lodgepole pine cover best continue along the trail, crossing Falls Creek on a sturdy footbridge. At the highest spring flows, it can be a thigh-deep wade to approach the bridge—take care! Soon you reach a junction (6,600'; 38.01129°N, 119.73251°W; mileage measured to here) with a trail that leads to tree-sheltered campsites along Lake Vernon’s northwest shore. Most lakeside campsites are small, and almost all are well hidden from the trail; the largest one is about one-third of the way north along the western shore in a large stand of lodgepole pines. There is also a large campsite beyond the north end of the lake close to where the creek angles from northeast to north. The lake, mostly shallow and lying at about 6,564 feet, is one of the warmer park lakes for swimming.

Common yellow monkeyflower in a small pool on slabs Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

DAY 3 (Lake Vernon to Laurel Lake, 4.4 miles): From the aforementioned junction, the main trail climbs left (southwest) to mount a shallow ridge, loops a little north, then resumes a southwest bearing following a route marked by cairns across smooth glacier-polished granite rimming the Falls Creek canyon. Climbing again, you reenter forest cover, and after 1.8 miles reach a moraine-crest junction with the trail leading right (northeast) to Jack Main Canyon. Your route is left (southwest), toward Laurel Lake and Hetch Hetchy. Ahead your trail winds down through a landscape burned repeatedly over the years and therefore mostly lacking shade but sporting a plethora of wildflower gardens due to abundant moisture and sunlight. An easy 1.25 miles brings you to a junction at the east edge of the Beehive, a meadow that is the site of an 1880s cattlemen’s camp (and campsites). You turn right (west) toward Laurel Lake, while continuing ahead (left; southwest) leads to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, tomorrow’s route.

Walk along the northern edge of the meadow, reaching another trail split within 200 steps, where you strike left (west) toward Laurel Lake’s south shore and outlet; right (north) is a sparsely used trail that loops to the lake’s north shore. You drop easily down into a gully, then cross broad Frog Creek, often a wet, bouldery ford in late spring and early summer. Climb steeply west up the creek’s north bank to a heavily forested ridge before gently dropping to good camps near Laurel Lake’s outlet. A brief lakeshore stint brings you to a junction (6,490'; 37.99432°N, 119.79651°W) with the north-shore trail—branching right (northwest) from here leads to more secluded campsites. Western azalea grows thickly just beyond the grassy lakeshore, a fragrant accompaniment to edible huckleberry and thimbleberry. Fishing is fair for rainbow trout, and swimming, especially in July and early August, can be wonderful.

DAY 4 (Laurel Lake to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, 7.5 miles): The final day is almost entirely downhill and on well-traveled trails. You begin by retracing your steps 1.4 miles to the northeast corner of the Beehive, now turning right (south) and skirting the long, narrow southeast lobe of the meadow. Traipsing through white fir and lodgepole forest and passing additional small meadows and seasonal rivulets, the 0.8 mile to your next junction is generally pleasantly shaded and low-angled as you traverse the slope above Frog Creek. At the upcoming junction, you continue straight ahead (left; south), while right (west) leads to Frog Creek and Lake Eleanor. All too quickly the conifer cover cedes to whitethorn on a slope that’s been repeatedly scorched by fires, most recently the devastating 2013 Rim Fire. In places there is barely a mature, seed-producing tree still standing, much less any with sufficient foliage to provide decent shade. A gradual descent brings you to a seasonal linear lakelet, nestled on the inside slope of a broad lateral moraine. Mounting the moraine, a long descent ensues, 1,000 feet down a narrow, winding trail that fluctuates between notably steep, pleasantly shallow, and occasionally annoyingly uphill. Note that camping is not permitted once you’re within 4 miles of the trailhead. Eventually, the slope pauses at a junction. Stay left (south), descending along a now-broad road tread, while the right-hand (westbound) trail was once a service road and leads to Miguel Meadow and Lake Eleanor.

The continued downhill walking is pleasant and the views rejuvenating, as you stare down to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and its southern sentinel, Kolana Rock. This slope was mostly burned in 2013, but the live oaks rapidly resprouted, providing welcome shade. 1.9 miles of well-graded switchbacks brings you to the junction you passed on Day 1 near the shore of Hetchy Hetchy Reservoir. Here left (east) leads to Rancheria Falls, while you turn right (west) and retrace your steps the final mile around the reservoir, through the tunnel and across the dam to the trailhead.

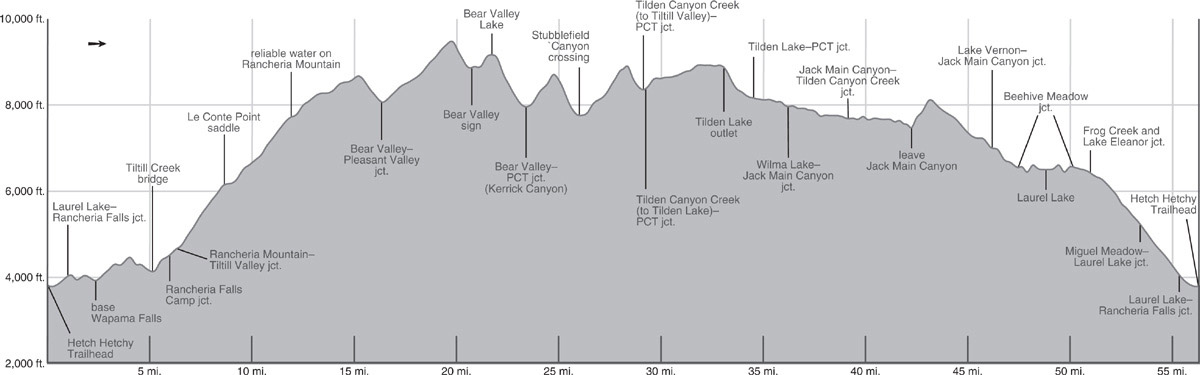

trip 39 Grand Tour of Northwestern Yosemite

Trip Data: |

38.09391°N, 119.61972°W (Tilden Lake outlet); 56.3 miles; 7/1 days |

Topos: |

Lake Eleanor, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Ten Lakes, Piute Mountain, Tiltill Mountain, Kibbie Lake |

HIGHLIGHTS: The names Rancheria Mountain, Tilden Lake, and Jack Main Canyon stir visions of sought-after, remote treasures to anyone who has stared at a map of Yosemite. This long loop out of Hetch Hetchy Reservoir takes in the best of northwestern Yosemite, traveling both popular and lesser-used trails.

DAY 1 (Hetch Hetchy Trailhead to Rancheria Creek, 6.0 miles): Follow Trip 37, Day 1 to the Rancheria Falls streamside camp (4,515'; 37.95633°N, 119.71521°W).

DAY 2 (Rancheria Creek camping area to Rancheria Mountain, 5.9 miles): The next morning, return to the main trail, turn right, and ascend 0.3 mile moderately uphill to a junction where left (northeast) leads to Tiltill Valley (Trip 38), while you turn right (southeast), crossing Rancheria Creek on a bridge after 0.15 mile. The powerful frothing water is hypnotizing in spring, while well-worn potholes and slabs invite swimmers in late summer. Fill up on water at this creek, for your next source is at tonight’s campsite 3,000 feet higher on the slopes of Rancheria Mountain. Your trail commences a 1,500-foot switchbacking ascent up generally open slopes, since most tree cover was removed by a 1999 fire and the regrowing black oaks currently provide little shade. At 2.2 miles past Rancheria Creek, the trail tops a 6,200-foot nose, littered with gravel and boulders, all glacial deposits. Detouring a mile west from here leads to the summit of Le Conte Point, an easily climbed, spectacular viewpoint.

Onward, your trail traverses a half mile east along sandy slopes, most places charred by fires at least once during the past two decades, to the head of a minor hanging canyon. Here you encounter the first white firs of your journey. The ascent resumes on dusty switchbacks up past some fire-cleared forest openings, showy during the June wildflower bloom and later dry and parched, when you’ll step across one dry gully after another. At 6,750 feet, you swing onto a south-facing chaparral slope and can look south across the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne River to the rolling upland region across it; take the time to enjoy these views, for they will be hidden later. Beyond, the trail leaves the benches and broken granite slabs and progresses up a slope shrouded with thickets of manzanita and whitethorn, a species of ceanothus that is the bane of hikers traveling the park’s lesser-used midelevation trails for years following fire. Where more moisture irrigates the soils, willows dominate and water-loving flowers like crimson columbine decorate the trail verges. The trail first ramps upward, then begins to zigzag more tediously, finally leaving the burned areas and re-entering forested cover at around 7,600 feet. Not long afterward, the trail approaches a reliable stream. Above its eastern bank are campsites on a mostly open, gentle, gravelly slope with scattered red fir cover (7,711'; 37.95199°N, 119.65208°W). Additional camping options exist over the next 2.5 miles as you follow the creek up Rancheria Mountain. Because tomorrow is a longer day, you may wish to continue a little farther.

Bear Valley Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

DAY 3 (Rancheria Mountain to Bear Valley Lake, 9.8 miles): Onward, your trail ascends beneath lodgepoles and red firs, soon entering the shallow drainage of a second, smaller creek. You briefly parallel the creek upward, then angle northeast away from it, ascending up over a morainal divide back to the creek along which you camped, 1.7 miles beyond where you first crossed it. Now at an elevation of about 8,250 feet, in peak flowering season, you are standing in almost head-high stalks of larkspur, lupine, fireweed, umbrella-leaved cow parsnip, and four-petaled monument plant, and, of course, many shorter species, including lacy meadow rue, purple aster, white yarrow, yellow ragwort, aromatic pennyroyal (a mint), and leather-leaved mule ears. Under all these, at times, can be a mat of Jacob’s ladder. There are additional campsites in this vicinity. From this flower garden, your path turns east-northeast up a broad, shallow swale and soon leaves the lush surroundings behind as it climbs gently along dry volcanic slopes of a broad, low ridge emanating west from the northeast summit of Rancheria Mountain.

RANCHERIA MOUNTAIN

The view from the summit of Rancheria Mountain to the bottom of Pate Valley, more than 5,000 feet below, is well worth the half mile detour south. The easiest route is to leave the trail shortly after you surmount the ridge, just under 8,600 feet (37.96630°N, 119.60842°W). Head slightly southeast toward a broad saddle, then turn southwest and follow the ridge a little under 400 feet up to the summit. Abundant flowers greet you throughout the walk.

A mile past the second creek crossing, your way becomes a ridgetop amble, bringing you to the trail’s high point on Rancheria Mountain, at 8,680 feet. Ahead, you have a 1.2-mile-long, two-stage descent of about 600 feet, first to cross one minor saddle, then to reach a second, larger one. Five switchbacks spare your knees on the descent, and, where the trees disperse momentarily, you look northeast to distant Sawtooth Ridge and closer Volunteer Peak. A short distance later, atop an 8,060-foot saddle, you reach a junction where you trend left (north) toward Bear Valley, while right (east) leads to Pleasant Valley and beyond to Rodgers Canyon and Pate Valley.

The trail to Bear Valley gradually ascends a conifer-clad slope that is the divide between Piute Creek to the east and Rancheria and Breeze Creeks to the west. After crossing a timbered saddle, climb north up a steep, shaded pitch to a small, grassy pond fringed with poisonous Labrador tea (and campsites)—detouring east from here leads to an astounding view of Pleasant Valley, far below. Continuing a half mile north along a sandy ridge leads to the willowy east bank of an unnamed creek. Then, after another half mile, the trail crosses the creek and climbs northwest through a grassy meadow to top a lateral moraine.

Soon you find yourself in the open, perched drainage of another unnamed creek that you ascend through a broad flower-filled meadow, reminiscent of less rugged Sierra landscapes farther north. In places the trail is faint, but walking upslope you cannot miss your goal: a 9,490-foot saddle flanked by huddled whitebark pines and hemlocks. Below is pastoral Bear Valley, overshadowed by knife-edge Bear Valley Peak. Bear Valley is reached by winding 500 feet down a steep hemlock-bedecked slope, lush with flowers. As the gradient lessens, the trail turns northwest to reach the south side of meadowed Bear Valley. Here the path can be lost for some 500 feet across the hummocky, frequently soggy grassland—traipse straight (due north) across the meadow, not left (west) in the direction of use trails leading to campsites, and you’ll soon reach a handy metal sign proclaiming you’re in Bear Valley.

On the meadow’s north side, the trail is immediately obvious again, climbing easily over a forested moraine, then dropping to the east end of a small, hospitable lakelet circled by lodgepoles and western white pines. Just a minute north of it, you hop across Breeze Creek and ascend northeast along it over open, slabby terrain. After about 300 feet of elevation gain, the trail levels off, enters a delightful open stand of pines and hemlocks, and quickly arrives at the outlet of long-awaited Bear Valley Lake (9,154'; 38.03438°N, 119.57920°W; unnamed on maps). With picturesque islets and a slab-ringed shoreline, this shallow gem provides a stunning foreground for soaring, photogenic Bear Valley Peak (Peak 9,800+; also unnamed on maps). Excellent camps lie among conifers back from the north shore.

DAY 4 (Bear Valley Lake to Tilden Lake, 10.9 miles): From Bear Valley Lake’s outlet the trail leads a short distance northwest to a small gap between two low domes and begins a 1,200-foot descent north into Kerrick Canyon. For the first 400 feet, the descent is shaded by hemlocks and western white pines, yielding to a denser lodgepole pine and hemlock forest lower down. Finally reaching morainal till rearranged by the sometimes raging Rancheria Creek, your descent abates and you turn east through dry lodgepole flats to arrive at a junction with the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), 1.6 miles beyond last night’s campsite. You take the left-hand (north) option toward Rancheria Creek, while right (east) leads to locations to the east, including Buckeye Pass and Seavey Pass (Trip 31).

Immediately, you cross voluminous Kerrick Canyon’s bouldery Rancheria Creek, often a rough ford through mid-July—indeed generally considered the most dangerous of the northern Yosemite crossings and best crossed by mid-morning. After crossing the creek, the PCT passes a north-bank spur to popular campsites and follows Rancheria Creek briefly downstream. It then begins a steep rocky climb out of the drainage. Necessary breathers allow time to admire the dramatic cross-canyon views of Bear Valley Peak and Piute Mountain. Ascending first a brushy slope and later crossing broken slabs, the trail eventually gains 700 feet in elevation to reach a shallow gap near the west end of a small lakelet (with small campsites).

PARALLEL CANYONS

Northern Yosemite is famous for its series of near-parallel, glacial smoothed canyons: Jack Main, Tilden, Stubblefield, Kerrick, Matterhorn, and Virginia to name a few. The upper reaches of these gems are lush and pleasantly graded, making for fast, easy walking. Your route, following the PCT for a stretch, instead cuts across these canyons. This is an anything but gentle endeavor because tall rugged ridges separate them, earning this section of trail the name “The Washboard.” Since this is the route on which most people experience northern Yosemite, the complaints about the knee-shocking descents and lung-searing ascents have become infamous. On your next trip to northern Yosemite, pick a route that emphasizes the length of a canyon, such as Trip 77 or 80 in this book, or drop your pack and walk up Stubblefield Canyon, for a very different adventure.

Proceeding north from the gap, a multitude of short, steep, cobbly switchbacks lead north. Crossing the diffuse outlet of Lake 8,896, which spills across the trail, you continue rockily downward, dropping almost 1,000 feet to the mouth of Thompson Canyon, then turning west and making a shady, short descent as you slowly converge with the canyon’s stream. You step across the outlet creek from Lake 8,896 once more, then enter a lush red fir forest near the confluence of the Thompson Canyon and Stubblefield Canyon flows. Now 2.6 miles beyond the Kerrick Canyon junction, you cross the combined flow; with no logs spanning the wide creek, it is always a wade, but with a slow current it isn’t dangerous. There are campsites on both sides of the ford.

Continuing downcanyon on the opposite bank, after a quarter mile, you leave the shady floor for slabs and brushy slopes, beginning a sometimes-steep climb toward a gap in Macomb Ridge. The walking is slow and rocky, with false passes repeatedly dashing your hopes that you are “almost on top.” After crossing a corn lily meadow, the trail turns northwest, leading to the true highpoint, then descends 550 feet into Tilden Canyon. As the trail levels out you reach a junction, 3.1 miles past the Stubblefield crossing, where you turn right (north), still following the PCT, while left (south) leads to Tiltill Valley. Just 0.1 mile later is a second junction, where the PCT trends left (northwest) to Wilma (not Wilmer, as appears on some signs) Lake, while you leave this thoroughfare, taking the right-hand (northeast) option to Tilden Lake. Note: If you want to shorten your loop, you could at this point turn toward Wilma Lake, with campsites in 1.2 miles at the lake’s eastern shore, and the next day continue straight ahead (west) 0.6 mile to rejoin the main circuit at a junction in Jack Main Canyon. This saves a total distance of 5.2 miles, but you miss Tilden Lake.

Continuing toward Tilden Lake, the now smaller trail tracks Tilden Canyon Creek north in a narrow drainage flanked by Macomb and Bailey Ridges. You stroll through a dense lodgepole forest with a lush understory of dwarf bilberry. Skirting first the western edge of a shallow pond, then a larger, equally shallow lake, you reach the headwaters of the Tilden Canyon Creek drainage and descend just slightly to Tilden Lake—and the Tilden Creek drainage. More than 2 miles in length, Tilden Lake is Yosemite’s longest lake, but it pinches to less than 0.1 mile in width in places. Your route skirts the southern shore of the lake; soon after the trail turns decidedly westward, you can head north from the trail to find sandy campsites nestled among slabs with stunning views upcanyon to Saurian Crest. If you seek more sheltered campsites, continue west on the trail until you reach Tilden Lake’s outlet (8,890'; 38.09391°N, 119.61972°W), cross to the north side, and follow the north shore, encountering a selection of campsites as you walk the first 0.75 mile of shoreline.

DAY 5 (Tilden Lake to Jack Main Canyon, 6.7 miles): Tilden Creek spills steeply from Tilden Lake’s outlet, dashing toward Jack Main Canyon through a delightful hemlock forest. Your trail switchbacks beside it, with views across the canyon, up Chittenden Peak’s steep black-streaked walls, and to the tumbling creek beside you. After a nearly 600-foot drop, the gradient eases, and you descend more gradually through lodgepole forest, passing a small tarn en route to a ford of Falls Creek. Beyond, you pass some small campsites and arrive shortly at a junction with the PCT. Here you turn left (south), while right (north) leads to the headwaters of Falls Creek and into Emigrant Wilderness at Dorothy Lake, the route of Trip 31.

Your route now descends alongside Falls Creek for nearly 8 miles. For the 1.7 miles to your next junction, the meandering creek is mostly hidden from view by a veil of lodgepole pine, as the trail crosses intermittently onto slabs, then back into forest. At the north end of an expansive lodgepole flat, you pass a ranger cabin on the right, and soon thereafter a junction where you continue straight down Falls Creek, while the PCT is the left (east) branch that almost immediately fords Falls Creek and reaches Wilma Lake.

Continuing through the lodgepole glade, you pass a selection of large campsites, then trending east to round a small knob, you pass a stock fence. This marks the start of the Jack Main Canyon Yosemite lovers come to see—Falls Creek tumbling, dashing, falling across granite slabs, punctuated by swimming pools (at low flows) and, where the gradient eases, a deep, aqua-colored meandering channel with steep domes behind. The next mile or so is probably the showiest section—first broad granite slabs with a thin veneer of water, then a narrower gorge with cascades and potholes. The trail skirts to the northwest across polished slabs, blasted in places for easier passage. Then quite suddenly, the river pours into a broad, flat meadow, 0.75 mile in length, and the trail turns to follow the meadow-slab boundary.

The meandering river channel is now broad and deep—and mostly hidden behind dense willows. Next, passing through a granite gap, while the river detours south, you skirt a picturesque lake backdropped by a lichen-covered cliff. A short distance later you reach a junction with a cutoff trail heading left (southeast), leading to the trail descending to Tiltill Meadow.

Continuing right (straight ahead; southwest), another 0.1 mile of hiking brings you to the northeastern end of a long meadow known informally as “Paradise Valley.” Along its fringes you will find a selection of campsites. Lodgepole pine groves house the biggest sites, including a large stock camp, while smaller tent sites can be found among slabs ringing the meadow (7,670'; 38.04672°N, 119.67132°W).

DAY 6 (Jack Main Canyon to Laurel Lake, 9.5 miles): You begin this day walking to the western end of Paradise Valley, where Andrews Peak, an impressive dome, commands the view south, and Mahan Peak lies to the north. Their ridges come together, pinching the meadow closed, and the trail detours north across slabs. As it descends back to river level, you sneak along a narrow isthmus between the stream and an aspen-bordered pond that lies just north of the trail, fed by groundwater not the stream. Winding northward, you pass another beautiful lakelet. It is striking how these lakes and the adjacent river, separated by only 30 feet in places, are not linked by channels. Continuing down, the never-fast trail undulates moderately, alternately visiting sunny benches of glaciated granite dotted with huckleberry oak thickets and precariously rooted western junipers, as well as pocket stands of lodgepoles and stately red firs, underlain by a thicket of ferns. Campsites are sparse and tiny, but swimming holes abound.

Descending a long run of stone steps, you reach the point where the trail parts ways with Falls Creek, the creek descending steeply toward Lake Vernon, while you begin a 600-foot, 0.9-mile climb to the crest of Moraine Ridge. Midway, you transition from granite slab to deeper soil with stands of trees, indicating you’ve just crossed onto the morainal deposits for which the ridge is named. From the high point you have just over a 3-mile descent along Moraine Ridge, a generally gradual, easy, sandy walk—it would be perfect were it not for the lack of shade, the aftermath of fires in the past decades. The route stays mostly west of the edge, but detour east to its crest at least once to gaze out across the granite slab country about Lake Vernon.

Eventually you reach a junction, where your route is right (southwest), toward Laurel Lake and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, while the lateral to Lake Vernon heads left (northeast; Trip 38). Ahead your trail winds down through a landscape burned repeatedly over the years and therefore generally lacking shade but sporting a plethora of wildflower gardens due to abundant moisture and sunlight. An easy 1.25 miles brings you to a junction at the east edge of the Beehive, the site of an 1880s cattlemen’s camp (and campsites), where you turn right (west) toward Laurel Lake, while straight ahead (left; southwest) leads to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, tomorrow’s route.

Walk along the northern edge of the Beehive to reach another trail split within 200 steps, where you strike left (west) toward Laurel Lake’s south shores and outlet, while right is a sparsely used trail that loops to the lake’s northern shore. You drop easily down into a gully, then cross broad Frog Creek, often a wet, bouldery ford in late spring and early summer. Climb steeply west up the creek’s north bank to a heavily forested ridge before dropping gently to good campsites near Laurel Lake’s outlet. A brief shoreline stint brings you to a junction (6,490'; 37.99432°N, 119.79651°W) with the north-shore trail—branching right (northwest) from here leads to more secluded campsites. Western azalea grows thickly just back of the locally grassy lakeshore, a fragrant accompaniment to tasty huckleberry and thimbleberry. Fishing is fair for rainbow trout, but swimming, especially in July and early August, can be wonderful.

DAY 7 (Laurel Lake to Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, 7.5 miles): Follow Trip 38, Day 4 to the Hetch Hetchy Trailhead.