INFORMATION AND PERMITS: This trailhead lies on the boundary of Stanislaus and Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forests, accessing Emigrant and Hoover Wilderness Areas, and is administered by Stanislaus National Forest. Permits are required for overnight stays, but there are no quotas. Permits for this trailhead are most conveniently picked up at the Summit District Ranger Station, located at 1 Pinecrest Road, in Pinecrest, California. If you will be arriving outside of office hours, call 209-965-3434; you can request a permit up to two days in advance and it will be left in a dropbox for you. Campfires are prohibited above 9,000 feet, as are campfires within a half mile of Emigrant Lake. Bear canisters are required if you camp in Hoover Wilderness or Yosemite National Park. Trip 31 enters Yosemite National Park, and once in the park, pets and firearms are prohibited.

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: This trailhead is located exactly atop Sonora Pass along CA 108. This is 72.6 miles east of the CA 108–CA 120 junction and 14.7 miles west of the CA 108–US 395 junction. There is a small parking area directly across from the trailhead and additional parking spaces and toilets along a spur road 0.2 mile to the west. The closest water is, to the east, at the Leavitt Meadows Campground (adjacent to the trailhead) or, to the west, at the Kennedy Meadows Trailhead (and adjacent campgrounds).

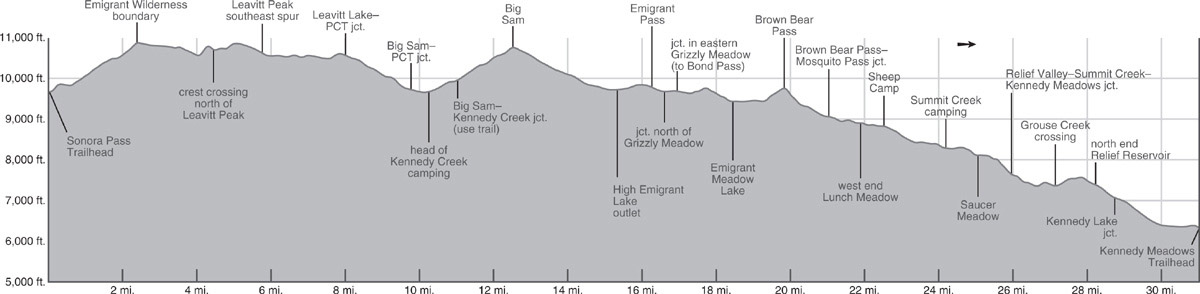

trip 30 Big Sam and Grizzly Meadow

Trip Data: |

38.19436°N, 119.63009°W (Grizzly Meadow); 31.0 miles; 4/1 days |

Topos: |

Sonora Pass, Pickel Meadow (just briefly), Tower Peak, Emigrant Meadow |

HIGHLIGHTS: With splendid views, geological and botanical intrigue, and the opportunity to follow two historically important routes, much of this walk is a “highlight.” The diverse terrain includes lakes, meadows, creeks, granite slabs, volcanic bluffs, and a peak that lies just 150 feet off the trail.

HEADS UP! Kennedy Meadows Resort runs a regular shuttle service to Sonora Pass, facilitating the trailhead logistics for this shuttle hike. Check out their website at kennedymeadows.com to determine the current schedule; click on the “PCT Hikers” link.

HEADS UP! This first day is long in distance but has relatively little elevation gain. Since the springs at the headwaters of Kennedy Creek are the first reliable on-trail water source, only start on this walk if you are confident you can complete the distance in a day.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: From the Sonora Pass Trailhead, continue 9.1 miles west along CA 108. Turn south onto the signed spur road to Kennedy Meadows. At 0.5 mile down the road, turn left (east) into a large U.S. Forest Service trailhead parking area with toilets and hiker campsites, requiring a wilderness permit and limited to a 1-night stay. The actual trailhead is an additional 0.5 mile down the road at the Kennedy Meadows Resort (lodgings, café, saloon, store, pack station). You can drive here to pick up packs and passengers, but leave your car at the aforementioned Forest Service parking lot.

DAY 1 (Sonora Pass Trailhead to Kennedy Creek headwaters, 10.2 miles): Departing south from Sonora Pass, the famous Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) winds briefly through multistemmed whitebark pine clusters, then traverses onto an open volcanic slope that is one of the Sierra’s best wildflower gardens. Late-lasting snowfields and the nutrient-rich volcanic rocks nurture dense expanses of flowers: the mule ears, western blue flax, scarlet gilia, California valerian, and mountain monardella are among the most colorful, although several dozen species grow here. The trail crosses two drainages, the first unnamed and the second Sardine Creek, before traversing south, then west, and finally north across a broad bowl beneath volcanic cliffs. Parts of this slope hold long-lasting snow—take care if you’re hiking in June (or into August in a high snow year).

About 2 miles from the trailhead, the trail is back on the actual crest of the Sierra, passing through different phenomenal wildflower displays—now they are mainly cushion plants, some rising less than an inch above the soil, and include silky raillardella, showy penstemon, hoary groundsel, Pursh’s milk vetch, and woolly sunflower. Looking far down to CA 108, the trail traipses across a west-facing slope high above Blue Canyon; the whitebark pine and currants have been wind-pruned into smooth, flat mounds. Eventually the trail crosses back to the east side of the crest, passes a small tarn, and climbs briefly but steeply to a saddle, from which you look 400 feet down upon Latopie Lake.

VOLCANIC ROCK

The volcanic rubble you’re walking across is part of the Relief Peak Formation. It includes lava flows of various chemical compositions, lahars (mudflows triggered by volcanic eruptions), and what is termed “autobreccia.” Autobreccia forms when the erupting magma causes either previously deposited volcanic rock or the underlying bedrock (in this case granite) to fracture and this fractured rock is engulfed in the magma. All the places you see chunks of one rock enveloped in a volcanic matrix are “autobreccia of volcanic origin.”

Continuing to traverse with little elevation gain or loss, the trail cuts across the front of rugged, multicolored volcanic bluffs; this is one of the rockier trail sections underfoot. A broad arc leads to an east-trending spur (with a late-lasting snowbank) and then across another broad bowl, now with Koenig Lake far below.

LEAVITT PEAK

From the base of the aforementioned snowbank, it is just 0.7 mile up a ridge to the summit of Leavitt Peak. If you have spare time, it is a straightforward, albeit rock-and-talus covered, ridge walk with 750 feet of elevation gain to the summit. Once you’re on the ridge, there are vestiges of a use trail. For reference, you’ve completed just over 5 miles and have 5.2 to reach tonight’s camp. Leave the trail at 10,648'; 38.27906°N, 119.64363°W.

Back on a west-facing slope, you now look down upon the Kennedy Creek canyon to triangular Kennedy Lake and across to Molo, Kennedy, and Relief Peaks, the trio of volcanic summits to the southwest. Granitic Tower Peak surges into view to the southeast. You saunter across the volcanic rocks, admiring sky pilot (the northern variety, Polemonium pulcherrimum), narrow leaved fleabane, and Eaton’s daisy (both rare species in most of the Sierra). Ahead, you reach a junction with a mining road climbing steeply from Leavitt Lake (left, east); you head right (south), now on the old road.

A short distance later the road cuts back onto the east side of the ridge and begins a long switchbacking descent into Kennedy Canyon. In line with Leave No Trace principles, you are encouraged to ignore shortcut trails down the slope and stick to the mining road. The coming 1.6 miles offer few botanical or geologic distractions, but the road tread is innocuous and of a sufficiently low gradient to be easy on the knees. Where the terrain levels, you reach a junction where you continue right (south) on the mining road, while the PCT turns left (east) to descend Kennedy Canyon (Trip 31). There are a few campsites a short distance along the PCT, near clusters of trees.

After so many barren miles, the upright whitebark pine clusters and grassy ground cover with a dense speckling of Leichtlin’s mariposa lilies are most welcome—and unexpected, for you are still on the ridgetop. About 0.4 mile from the junction you’ll notice sandy patches between whitebark pine to the right (west) that are ideal campsites, some even offering open views toward Kennedy Peak (9,655'; 38.23994°N, 119.61190°W). In the gully just 0.1 mile farther is a delightfully reliable robust spring, the headwaters of Kennedy Creek.

DAY 2 (Kennedy Creek headwaters to Grizzly Meadow, 7.0 miles): In the morning, regain the old mining road and begin a long but moderately graded uphill to the summit of Big Sam (labeled only as Peak 10,825 on the USGS 7.5' topo maps). The trail first trends west beneath Peak 10,827 and its western satellite, then turns south to curve into a high basin. (Note: There is one steep, late-lasting snowfield on this section. If present, you’ll be able to see it from your campsite and will probably wish to avoid it—the best option is to walk about 0.2 mile down Kennedy Creek. You’ll then see a rough trail, the old Kennedy Creek Trail, climbing up a rib and cutting beneath the snowfield to reunite with the mining road higher up.)

The trail winds up through the high bowl, hopscotching from color to color as you move between volcanic rock types. Looping across a band of krummholz whitebark pine, the trail ascends across dry west-facing slopes where singlehead goldenbrush and woolly sunflower are common, across a north-facing slope where Eschscholtz’s buttercups emerge as the snow melts, and up six switchbacks to the summit of Big Sam (10,825'). The few-step detour from the trail to the summit is well worth it—the view from Big Sam is astounding. Standing high above the surrounding landscape, you look south upon the Emigrant Lakes Basin with its broad, shallow, grass-ringed lakes surrounded by granite ribs. In the distance you look toward Yosemite’s highest summit, Mount Lyell, and neighboring Mount Maclure and to the Clark Range. Closer are the peaks on the northern Yosemite boundary, crowned by Tower Peak.

Continuing toward Emigrant Pass, think about the rich human history of the area as you plod downward—see the sidebar. First are more than a dozen switchbacks and then a long descent along the headwaters of the North Fork Cherry Creek to broad High Emigrant Lake. Mostly meadow ringed, the best campsites are on sandy flats on the lake’s south side. In case you’re wondering, the leaking dam across the lake’s outlet is one of 15 engineered by Fred Leighton, a cattleman, who wanted to ensure streamflow was maintained all summer to increase the spawning success of introduced trout.

HUMAN HISTORY NEAR EMIGRANT PASS

The road you are following was constructed in 1943 to reach a profitable tungsten mine along the East Fork Cherry Creek, about a mile below Horse Meadow. During World War II the United States needed tungsten, used to harden steel, and the approximately 16.25-mile road from Leavitt Lake was built to reach the prospects. Ore was hauled out for more than a decade, but of course the road was soon in disrepair from winter avalanches and mining was discontinued by the 1960s. Meanwhile, one of the first emigrant groups to cross the Sierra, some members of the Clark-Skidmore Party of 1852, crossed broad Emigrant Pass below you. They ascended the West Walker River, then the West Fork West Walker River to Emigrant Pass, descending to Emigrant Meadow Lake. While you’ve followed the mining road for much of the first two days of your journey, you will be following the emigrant route for the next day and a half.

Beyond High Emigrant Lake, the trail climbs gently to Emigrant Pass, the pass crossed by the emigrant wagons, and on down to the actual low point in the divide. Here is a junction with the trail ascending the West Fork West Walker River (Trip 34; left, east). You continue right (south), signposted for Grizzly Meadow and, walking beside an increasingly marshy meadow corridor beneath imposing Grizzly Peak, reach another junction after 0.35 mile, where you turn right (northwest) signposted for Brown Bear Pass, while left (south) leads to Bond Pass (Trip 34).

You cut across the notably marshy meadow corridor to an unmarked junction, where you trend right (west), while left (south) is a cutoff route to Horse Meadow. Near this junction, search for splendid—but usually small—campsites in sandy flats on the glacial-polished granite ribs surrounding lower Grizzly Meadow Lake (9,681'; 38.19300°N, 119.62799°W at junction). All sites have idyllic views of Grizzly Peak. There are also flat sandy areas farther west near upper Grizzly Meadow Lake, a little farther off the trail.

DAY 3 (Grizzly Meadow to Summit Creek, 7.0 miles): Today’s route begins by cutting back into the North Fork Cherry Creek drainage, by sidling out of the Grizzly Meadow Lakes bowl and dropping down to Emigrant Meadow Lake. The trail generally follows joint-defined sandy passageways and minor drainages, forcing it to jog north, then west, and north and west a second time as it drops to the giant broad basin holding Emigrant Meadow Lake and adjacent Emigrant Meadow. At the northeast corner of Emigrant Meadow Lake is a junction, where you stay right (northwest), signposted for Kennedy Meadows, while left (south) leads to Middle Emigrant Lake (Trips 28 and 29). You continue along the northeastern side of the lake, first through marshy meadows and then to extensive sandy flats and low-lying granite slabs near the northwestern tip of the lake (nearby camping). Crossing an ever-so-slight rise in the broad basin, the trail drops a token 10 feet to marshier Emigrant Meadow, where you cross the North Fork Cherry Creek again, a sandy wade until midsummer.

Bound for Brown Bear Pass, the trail’s gradient now increases and almost immediately crosses onto volcanic rock, although there are granite slabs just south of the trail. These are distinctly pink-hued due to mineral alterations that occurred as the volcanic rock flowed across it. Once atop Brown Bear Pass (9,763'), be sure to turn back and stare across the broad Emigrant Meadow basin and beyond to Saurian Crest, looking very much like the spiny back of a monstrous lizard, and Tower Peak. Looking west and northwest, the volcanic ridge extending from Molo Peak to Relief Peak and the summits of Black Hawk Mountain and Granite Dome are now in view.

Emigrant Meadow Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Your descent to the headwaters of Summit Creek is steep and rocky for the first 0.4 mile, then moderates as you approach Summit Creek and small campsites, some on whitebark pine–sheltered knobs and others in sandy flats. In stretches you walk through wetter vegetation alongside the creek, elsewhere on broken granite slabs, and yet other sections across sagebrush flats, decorated in season with wavyleaf paintbrush, spreading phlox, and Brewer’s lupine.

You reach a junction where you stay right (northwest), signposted for Kennedy Meadows, while left (south) leads across Summit Creek and over Mosquito Pass to Emigrant Lake (Trip 28). After a few more steps you reach the eastern lobe of Lunch Meadow (and a campsite). The trail traverses above the meadow, alternating between volcanic rubble and granite slab; you can’t help but think about how the two rock types erode into such different profiles, creating the disparate landscapes to either side of the trail. At the west end of the western Lunch Meadow lobe is another excellent campsite, with additional options were you to cross the creek. Continuing west, the trail remains close to Summit Creek, passing through small meadow strips and along sandy corridors between eroded granite ribs. A broad sandy flat and adjacent lodgepole pine stand is Sheep Camp, your last plausible camp until the suggested campsites another 1.7 miles ahead. Sheep Camp accommodates a larger group and if 8.5 miles isn’t too long for your final day, you may wish to stay here.

Ahead, the trail parts with Summit Creek and curves north, crossing a shallow sandy saddle and dropping steeply into a rocky valley. A 400-foot descent ensues, the trail working its way around outcrops and minor drop-offs; this is much slower walking than any of this trip’s previous downhill miles. Admire the fractured granite, rising ever higher above you: steep walls adorned with vertical fractures that dictate where erosion preferentially occurs. Slowly the valley opens a little, the gradient lessens, and to the east the slopes are volcanic again—as is the rock underfoot. For nearly a mile you then cross an endless progression of long-ago debris flows, interspersed with a few more-recent deeply incised flood channels. Look east at the pinnacled volcanic visage and imagine an immense summer thunderstorm that sends rocks and water tumbling down the myriad tiny passageways, the debris slowing as it approaches the stream corridor. Red fir thrive in the fine, nutrient-rich material and form a near monoculture. Continuing south, the trail crosses back onto granite slab and the terrain flattens enough to entertain camping. First you pass a slab knob east of the trail with a small selection of sandy sites (8,283'; 38.23433°N, 119.72074°W) and a short distance later a large site under red fir and lodgepole pine cover, also to your right (east). The forested flats in the direction of the creek are clearly marked as NO CAMPING, for they are fewer than 100 feet from water.

DAY 4 (Summit Creek to Kennedy Meadows Trailhead, 6.8 miles): Just past the campsites, the trail again diverges from Summit Creek, following a sandy corridor at the granite-volcanics boundary that leads to tiny Saucer Meadow, a little flower-filled marsh. Climbing over a minor saddle, you again cross fans of volcanic scree. East Flange Rock, the volcanic pinnacle due west, and Granite Dome dominate the view. To the north, you catch your first glimpses of giant Relief Reservoir. The slope steepens and the tread becomes rockier as you descend a scrubby, open slope with just the occasional juniper. Beyond, the trail is channeled into a cooler draw where dense white firs provide shade and seasonal trickles irrigate wildflower pockets. At its base is a junction, where you continue right (north), while left (west and south) leads into the Relief Creek drainage (Trip 29).

The route follows an easy-to-navigate corridor, separated from Summit Creek’s drainage by a blocky granite rib, initially through a lovely forest of aspen and white fir, then into more open terrain where towering Jeffrey pine and stringy-barked junipers predominate. You soon sense you’re walking just east of Relief Reservoir; indeed, if you were to head west, you’d find camping in sandy flats set back from the shore. Then, about one-third of the way north along the reservoir, you reach a shallow ford of Grouse Creek that can usually be crossed on an assortment of logs. To either side of the crossing, spur trails head west toward the reservoir’s shore and the best lakeside camping options. Climbing and dropping continually, the trail contours high above the reservoir on hot, sandy, brushy slopes with just the occasional Jeffrey pine or juniper providing dots of shade.

Toward the reservoir’s north end, you reach a series of overlooks, culminating in the best one; a distinct spur trail leads first to the vista point and then toward the Relief Reservoir dam itself. Dropping past rusting equipment used in the dam’s construction, numerous use trails depart left (west) to Summit Creek. Ahead is a signed junction, where your route continues left (north), while right (east) leads to Kennedy Lake. Crossing brushy slopes beneath a granite dome, the trail splits; the main trail switchbacks to the left (northwest), while the right-hand (more northerly) alternative is a steeper, 400-foot-shorter route used by some hikers. Just after the two routes merge you reunite with Summit Creek and cross a trestle bridge high above the tumultuous river, enjoying views to cascades upstream. Continuing north along the blocky, incised gorge, you soon spy Kennedy Creek to the east, tumbling down its steep boulder-and-bedrock-lined course. The trail descends the creek’s western bank, passing beneath impressively vertical—even overhung—black-stained walls. At the confluence with Kennedy Creek, the flow becomes the Middle Fork Stanislaus River—a mighty torrent of water in early summer that you admire as you cross a second bridge.

The valley now quickly broadens and the trail turns first west, then north at the start of Kennedy Meadows. You leave Emigrant Wilderness and pass a U.S. Forest Service trailhead sign. The final 1.0 mile to the trailhead is along a dirt road, sometimes under forest cover—a mix of Jeffrey pine, incense cedar, white fir, and juniper—and elsewhere at the meadow’s edge or just above the river’s banks. Where the meadow pinches closed, the road crosses a minor saddle. Dropping again, you quickly reach a gate and Kennedy Meadows Resort, the effective “trailhead,” although at least one person in your group will have to walk an additional 0.5 mile to the overnight parking area.

trip 31 Pacific Crest Trail to Tuolumne Meadows

Trip Data: |

37.87889°N, 119.35854°W (Glen Aulin Trailhead); 73.9 miles; 8/1 days |

Topos: |

Sonora Pass, Emigrant Lake, Tower Peak, Piute Mountain, Tiltill Mountain, Matterhorn Peak, Falls Ridge, Dunderberg Peak, Tioga Pass |

HIGHLIGHTS: The varied and incomparable scenery along this leg of the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) from Sonora Pass to Tuolumne Meadows offers emerald meadows, granitic and metamorphic peaks, jewellike lakes, bubbling creeks, panoramic views from ridges, and visits to deep canyons. These rewards more than justify the trip’s length and sometimes taxing ups and downs.

View to Kennedy Lake on the long traverse past Leavitt Peak Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

HEADS UP! Most people won’t want to carry more than 8–10 days of food (and can’t fit more in a bear canister), so the trip is divided into 8 days plus a layover day to have a midtrip rest. This translates into 10–11 miles on many days, making it one of the more strenuous trips in the book.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: The trip ends at the Glen Aulin Trailhead in Tuolumne Meadows in Yosemite. This is just off Tioga Road (CA 120) in Tuolumne Meadows, along the Tuolumne Meadows Stables Road at the base of Lembert Dome. The junction is located just 0.17 miles east of the Tuolumne Meadows Campground entrance, right after you cross the Tuolumne River, or 6.95 miles west of Tioga Pass. The “parking lot” is the dirt shoulder along the Tuolumne Meadows Stables Road with overflow parking available at the stables. Your trip ends at a gate at the west end of the road.

DAY 1 (Sonora Pass Trailhead to upper Kennedy Canyon, 10.1 miles): Follow Trip 30, Day 1 for 9.8 miles. At the PCT–Big Sam junction, you turn left (east) to continue along the PCT. After just 0.3 mile you’ll see a selection of small campsites to the north of the trail beneath multistemmed whitebark pine clumps (9,477'; 38.24739°N, 119.60987°W). There are permanent springs nearby.

DAY 2 (Upper Kennedy Canyon to Dorothy Lake, 10.6 miles): The well-built PCT tread leads easily down Kennedy Canyon, first through meadows with abundant wildflower color and shortly into bare lodgepole pine forest. You cross through a repeat avalanche corridor—the logs littering the ground all face the same direction, and many surviving trees are missing lower branches. The trail then crosses a robust creek and heads down through lusher lodgepole pine forest, regularly crossing spring-fed rills where meadow rue, California valerian, and monkshood all grow robustly. Ever deeper into Kennedy Canyon, the trail traverses a drier slope and drops to cross the main drainage, often necessitating a shallow wade, and just beyond passes small campsites. Ahead, the valley bottom is flatter, the trail alternately passing through pleasant lodgepole pine forest and across small grassy benches above the gurgling creek. The route is on volcanic substrate until you come to the mouth of Kennedy Canyon; here the trail jogs briefly north, then turns decidedly southeast and you step onto granite slab. Nearby are some splendid campsites perched high above the river.

As the Kennedy Canyon creek drops more steeply to merge with the West Fork West Walker River, the PCT turns south, beginning a long traverse parallel to (and above) the West Fork West Walker River. Hawksbeak Peak on the Yosemite boundary is exceptionally impressive from here, a steep, angular fin shooting skyward. In 0.5 mile you pass a small waterfall dropping down a volcanic gorge (worth a look) and continue just at the forest-talus slope boundary, first passing beneath soaring volcanic ridges, then transitioning back to granite slab and winding your way along the fringe of Walker Meadows. Passing a large campsite to the right (south), you reach the West Fork West Walker River, crossed on a stout bridge. Just beyond is a junction, where you stay right (southwest) on the PCT toward Dorothy Lake Pass, while left (southeast) leads to the Long Lakes and Fremont Lake (Trips 32–36).

Ascending the West Fork West Walker River, in just 0.2 mile you reach a second junction (and more excellent campsites), where the PCT trends left (nearly due south; again signposted for Dorothy Lake Pass), while a trail toward Cinko Lake (Trip 33) and Emigrant Pass (Trip 34) diverges right (southwest), continuing along the river’s southeast bank. The PCT ramps up slabs colored by bursts of Leichtlin’s mariposa lily, mountain pride penstemon, and Brewer’s aster, slowly diverging from the river. After 0.5 mile the trail turns east, winding along forested corridors between granite slabs and past early-drying tarns. Turning south again, the trail leaves the conifer cover for bare slab and you’ll discover you’ve left the granite for a mosaic of older metavolcanic and metasedimentary rocks, including bands of marble and a wall sparkling with garnets.

Ducking briefly back into a cool, sheltered draw shaded by hemlock and lodgepole pine, you reach another junction where the PCT turns left (east, then southeast), while right (west) is another route to Cinko Lake (Trip 33); there are campsites at the junction. Just beyond you cross a small creek on rocks or logs. Still on metavolcanic rock, a 0.8-mile segment takes you across a broad saddle cradling a series of tarns (and more possible campsites) to a junction with a trail ascending Cascade Creek from Lower Piute Meadow (to the northeast; Trip 34). The PCT continues right (south), passing a pair of heath-bound tarns, looking down upon an often-flooded meadow, and reaching the banks of Cascade Creek in a pocket of lodgepole pine. The river must be crossed, requiring either a delicate log-and-rock hop or a broad wade; an old footbridge is long gone. The trail then follows up the creek’s eastern bank, winding up bare, broken slabs between scattered lodgepole pine. The creek to your side is forever spilling down little falls, for the rock erodes in a blocky fashion. In a small patch of willows, just below 9,200 feet (38.18915°N, 119.56930°W), the PCT inconspicuously crosses Cascade Creek. At high flows, stay on the more obvious eastside trail, which leads to an easier crossing on logs and rocks at Lake Harriet’s outlet; the eastbank use trail also leads to a fine selection of camps along Lake Harriet’s east shore.

Across Harriet’s outlet, the use trail and PCT reunite, continuing around Lake Harriet’s western shore, then resuming a steady ascent up broken slab and completing six tight switchbacks to a tarn-filled flat. Here an unmarked spur trail leads west to Bonnie Lake (limited campsites). A short distance later the trail crosses into the drainage where Stella and Bonnie Lakes lie, converging with Stella Lake’s outlet as the trail approaches the lake. Stella is a gorgeous lake with an intricate shoreline but offers very few campsites. The trail winds across gray diorite slab north of the lake, then barely rises to reach the summit of Dorothy Lake Pass, an elongate notch that marks your entrance into Yosemite National Park.

Looking forward, giant Dorothy Lake fills the valley ahead, with light-colored Tower Peak peering out to the southeast and the dark granite grenadiers of Forsyth Peak to the south. A slight descent leads to Dorothy’s northern shore. You pass a few acceptable campsites early in your traverse but should continue to Dorothy’s southwestern end for the night. Until late in the summer, water seeps from the base of upslope slabs, and endless rills irrigate the slopes, nurturing splashes of color (shooting star, elephant heads, goldenrod, paintbrush, whorled penstemon, pussypaws, and false Solomon’s seal) and expanses of corn lilies and willows. The trail can be quite muddy—take care to walk on the wet tread or balance on rocks, instead of damaging the surrounding subalpine turf. At the lake’s southwest end you’ll see a sign pointing stock parties southeast around the lake; hikers should follow this use trail as well. They needn’t walk the full 0.4 mile to the big stock campsites, but just a few hundred feet to some excellent campsites beside clusters of lodgepole pine (9,429'; 38.17422°N, 119.59511°W).

DAY 3 (Dorothy Lake to Wilma Lake, 8.7 miles): Beyond Dorothy Lake, the trail passes a satellite lakelet and meadows overgrown with straggly, crowded lodgepole pine, likely a legacy of meadow-trampling by sheep, cattle, or humans long ago. A brief descent brings you to, in quick succession, two trails that unite to climb northwest to nearby Bond Pass, the park’s boundary; you stay left (south) at each. A 600-foot descent follows, carrying you into the upper end of lush, damp, and stunning Jack Main Canyon, where the trail roughly parallels Falls Creek. This next stretch of trail is an idyllic series of tiny meadows interspersed with dense forest, all alongside the murmuring creek. To the east, somber Forsyth Peak and black-and-white Keyes Peak cap the canyon walls. Throughout the coming miles, endless trickles descend from the west, making for wet, muddy feet in early season; take care not to trample the surrounding vegetation in an attempt to keep your feet dry. The largest meadow stretch is verdant Grace Meadow, Falls Creek meandering lazily along its western side. In Grace Meadow—and the meadows you’ll pass to the south—you’ll find tiny campsites in the fringing lodgepole, but no large sites, for most of the ground is vegetated or sloping.

Chittenden Peak and its northern satellite serve as impressive reference points for gauging your southward progress; about where you pass them the canyon’s gradient steepens a little, ultimately leading to your first junction in 6.6 miles. You stay right (south) on the PCT, white left (east) leads to Tilden Lake. (Note: As described in Trip 39, Days 4–5, you could detour to Tilden Lake and rejoin the PCT tomorrow. Tilden Lake doesn’t lie on the PCT but is one of northern Yosemite’s absolute highlights.) There are good campsites near this junction.

For the 1.7 miles to your next junction, the meandering creek is mostly hidden from view by a veil of lodgepole pine. The trail crosses intermittently onto slabs, then back into lush forest with a near continuous groundcover of dwarf bilberry. At the north end of an expansive lodgepole flat, you pass a sometimes-staffed ranger cabin on the right, and soon thereafter a junction where the PCT turns left (southeast) toward Wilma Lake, while the route down Jack Main Canyon stays right (south; Trip 39). Near this junction is a selection of excellent campsites alongside broad, generally lazily flowing Falls Creek (7,959'; 38.07386°N, 119.64678°W). There is also a small camping area tucked among trees at Wilma Lake’s southeastern end and in the flat due north of the lake, a little farther off-trail. Today will have been much easier than the previous two days, but if you’re thinking of continuing, note that it is just a hair under 5 miles to Stubblefield Canyon, where you’ll next have good camping and water in the same location.

DAY 4 (Wilma Lake to Rancheria Creek, 7.7 miles): You begin the day by fording Falls Creek (almost always wet feet) to reach a narrow isthmus separating Falls Creek from Wilma Lake. You then walk close to Wilma’s shore on elegantly constructed trail. Climbing above Wilma Lake, you wind moderately up a canyon, mostly through lush heath-carpeted lodgepole forest, pass two pleasant tarns, and reach a junction with the trail that has descended Tilden Canyon Creek from Tilden Lake (left; north). Here you turn right (south) to follow the PCT. In just 0.1 mile, you reach a second junction, where you stay left (southeast) on the PCT, while right (south) leads down Tilden Canyon Creek and ultimately to Tiltill Valley and Hetch Hetchy Reservoir. Now begins a nearly 30-mile stretch of trail accurately referred to as crossing the Washboard (see sidebar); first up is a 550-foot ascent over 0.65 mile to reach a gap in Macomb Ridge.

CROSSING THE WASHBOARD

Macomb Ridge is the first ridge in a series of northeast-southwest ridge-and-canyon systems you will tackle as the PCT pushes its way generally southeastward against the “grain” of what’s often called “northern Yosemite’s washboard country.” Northern Yosemite is comprised of a series of shallow near-parallel canyons—Jack Main Canyon is the first of these. As you experienced yesterday, walking up or down the canyons is easy going, but cutting across the steep granite ridges that separate them is not. Ascend a ridge, drop into the next canyon, and almost immediately ascend the next ridge, drop into the next canyon . . . until the mind reels and feet ache. Even so, the magnificent scenery of northern Yosemite is adequate reward for all your effort.

The descent into Stubblefield Canyon is slow and rocky. Near the top you pass through pleasant corn lily glades and token forest stands, but you soon transition to scrubby slopes—vast expanses of huckleberry oak and broken slab. Slowly you reach Stubblefield Canyon’s shady floor and turn northeast to follow the creek briefly upstream to a ford. With no logs spanning the wide creek, it is always a wade, but with a slow current it isn’t dangerous. There are campsites on both sides of the ford.

After traversing the lovely valley-floor red fir forest, the 0.4-mile hiatus from the washboards ends and you resume climbing, initially alongside Thompson Canyon’s creek. A mostly rocky tread leads up nearly 1,000 feet to the unnamed ridge between Stubblefield and Kerrick Canyons, crossing the outlet creek from Lake 8,896 twice en route. Surmounting the final short, steep, cobbly switchbacks you reach a shallow gap near the west end of a small lakelet (with small campsites).

Immediately descending again, the PCT drops down broken slabs and across brushy slopes, losing 700 feet to reach Rancheria Creek and Kerrick Canyon. Admire the dramatic cross-canyon views of Piute Mountain and Bear Valley Peak (Peak 9,800+, the steep granitic pyramid) to its west. The trail parallels Rancheria Creek briefly upstream, giving you a chance to absorb its often-turbulent flow. Voluminous and bouldery, during high runoff periods, the upcoming ford is generally considered the most dangerous of northern Yosemite’s many tricky crossings. There are campsites to either side of the ford. In early summer, water levels can drop more than a foot overnight, so if the creek looks frightening to cross, camp in the north bank sites (7,980'; 38.04554°N, 119.57287°W) and proceed across in the morning. (If you want to hike farther, there are additional sites in about 2 miles, along Rancheria Creek, and between 3.5 and 4.5 miles at tarns near Seavey Pass.)

DAY 5 (Rancheria Creek to Smedberg Lake, 11.3 miles): Today is a long day, but your pack should be feeling lighter and your legs stronger. If you have a layover day, you could split today over two days, hiking the 7.0 miles to Benson Lake and having a restful afternoon and morning before continuing to Smedberg Lake.

Just across Rancheria Creek, you meet a junction where the PCT continues left (south, then east), while right (west, then south) leads to Bear Valley (Trip 39). The trail follows the rushing creek upstream along the base of bluffs, the foot of Piute Mountain; north of the river equally steep cliffs rise toward Price Peak. Major joints cut across this area’s canyons, and this creek has eroded along them, resulting in an angular, joint-controlled course. Stretches of trail are in lush river bottom lodgepole and red fir forest (with a few small campsites) and elsewhere you cross dry flats displaying seasonal wildflower color. The narrow river canyon harbors evidence of past floods and avalanches, river cobble–strewn flats well above the creek’s banks and toppled trees. As the canyon narrows further, the trail makes a few unwelcome descents to bypass bluffs, followed in turn by additional ascents, eventually entering denser hemlock forest and climbing a steep slope to a junction, where you turn right (southwest) toward Seavey Pass, while left (northeast) leads to Kerrick Meadow and Buckeye Pass (Trips 75–77).

Looking back toward Volunteer Peak as you approach Benson Pass Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

You switchback up a steep slope bedecked with mountain hemlocks to a little passageway nestled between two domes, the actual drainage divide between Rancheria and Piute Creeks, and past a cluster of small tarns (and accompanyingly small campsites, including one at the larger lake a little west of the trail). Winding along past wildflower patches, between slabs, and through two beautiful unnamed gaps, you finally cross Seavey Pass, one of the few geographic points in the Sierra named a “pass” that doesn’t correspond with a drainage divide, but instead is just a passageway through the landscape. Your descent is gradual at first, continuing along a high shelf cradling additional lakes, all with slabs extending to their shores and some with worthwhile campsites. Scooting past the last in the series of lakes, the trail begins to drop more seriously; short switchbacks descend a steep, sheltered draw with lodgepoles and hemlocks.

The grade abruptly ends at a meadow at the imposing eastern base of Piute Mountain as the trail bends south to follow a tributary toward Piute Creek. Excepting brief forested glades, the trail diligently descends a dry slope where pinemat manzanita and huckleberry oak grow atop a mixture of light-colored granite and darker metamorphic rocks. This is a tough, slow descent for the track is steep, often gravelly, and you’re forever stepping over embedded rocks, continually breaking your stride. Rounding a corner, you see Benson Lake ahead. Your trail eventually reaches the valley bottom, and after a short, flat stretch through lush forest, you reach a junction with a spur trail that leads right (southwest) to the lake’s shore.

BENSON LAKE

Benson Lake lies 0.4 mile off the PCT. Hopefully you have time in your schedule to detour to its broad sandy beach, nicknamed northern Yosemite’s Riviera. The spur trail leads through nearly flat forest of white fir, lodgepole pine, and the occasional aspen. To your side is Piute Creek, a gushing torrent in early summer, transforming to a lazy trickle with big sandbars by early fall. Just beyond, you reach the famous Benson Lake beach, growing ever wider as the lake’s water level drops in late summer. Being at a relatively low elevation, Benson Lake is remarkably warm for swimming, or you can simply bury your feet in the warm sand while staring across the expanse of water and the dark cliffs descending from Piute Mountain. There are campsites at the back of the beach or in the forest at the far northeastern tip of the lake (7,591'; 38.02028°N, 119.52428°W). Fishing is good.

Continuing left (southeast) along the PCT, you must ford Piute Creek just where a substantial tributary merges; you cross both creeks independently, hopefully finding fallen logs. Should logs be missing, this is a dangerous crossing in early summer. Beyond, ascend a rocky knob and descend to the banks of the Smedberg Lake outlet creek—more of a raging stream in early summer when it is also a difficult ford.

Now begins an 1,800-foot climb as you head up a dry slope with occasional junipers decorating exposed knobs and small clusters of lodgepoles or hemlock growing on flatter creekside benches. Crossing the Smedberg Lake outlet creek again, you briefly enter a wet glade with possible campsites, then revert to dry, rocky terrain and gravelly corridors beside the cascading river. As you approach a headwall down which tumbles a small waterfall, you must again cross the creek, almost always a wade and a difficult one at high flow; head a little upstream of the trail for the best options.

Diverging from the creek, the trail’s gradient now increases and you quite rapidly climb 700 feet via steep, tight switchbacks; thankfully the walking is on soft forest duff beneath cool hemlock cover. Soon after the ascent eases, you reach a trail junction where the PCT turns left (east), toward Smedberg Lake, while right (south) leads past Murdock Lake (good campsites just south of the lake) and down Rodgers Canyon toward Pate Valley. Your route leads across a lovely lodgepole pine and hemlock shelf, dwarf bilberry carpeting the forest floor, and quite soon reaches another junction, where the PCT stays left (north), while a right (south) turn heads over a pass to Rodgers Lake.

Continuing toward Smedberg Lake, you wind along forested shelves and between narrow passageways in the pervading slabs and bluffs, all the while circumnavigating the base of near-vertical Volunteer Peak. Climbing again, admire the views west to massive Piute Mountain, Benson Lake visible at its foot. Stripes of trees across the landscape indicate where landscape-wide joints in the rock have allowed deeper soils to accumulate. Soon you crest a small ridge and begin your final descent to Smedberg Lake. Small single-tent sites present themselves in sandy patches among the slabs as you descend, or as soon as you reach the lake, turn left (north) to find abundant, and justifiably popular, campsites along the lake’s western edge (9,230'; 38.01270°N, 119.48802°W). Note this lake—like others nearby—is a mosquito haven until late July.

DAY 6 (Smedberg Lake to Spiller Canyon, 11.1 miles): Beyond the oasis of Smedberg Lake, you climb gradually alongside meadows, then more steeply as you trend toward Benson Pass and mount a series of sand-and-slab benches. The granite here decomposes to a coarse-grained sand that creates a decidedly slippery walking surface atop underlying slabs. Admire the giant rectangular feldspar crystals present in some of the outcrops. The gradient eases as you pass through a broad meadow that dries early and is covered with lupines in late summer. It segues to a narrow, sandy gully that, although unmarked on maps, is a good water source late into the summer. At its head the trail sidles south across a steep, gravelly, heavily eroded slope, leading to the flat summit of Benson Pass (10,125'). The pass boasts excellent views to the northeast.

Continuing east, the trail descends past knobs with multistemmed whitebark pine clusters, through more slippery decomposing granite, and then skirts north above a broad, often-dry meadow landscape (a few campsites at the perimeter). The topography again steepens, and while the trail descends steep switchbacks, the creek pours down a narrow slot in rocks. Below you reach a small meadow opening ringed by lodgepole pines (with campsites) and the banks of splashing Wilson Creek.

After crossing Wilson Creek atop logs or rocks, the trail turns southeast to begin a 2-mile descent to Matterhorn Canyon. There are massive avalanche scars down both canyon walls, a testament to the tremendous slides that sporadically tear down these slopes. The trees lay flattened, all pointing away from the flow of snow, meaning uphill directed trees were knocked down by slides that crossed the creek and flowed up the other side. Only beneath steep cliffs, where deep snow never accumulates, do mature forests persist. The beautiful slabs lining the creek also demand your attention—and perhaps a break. On this descent, camping is limited to a few small forested shelves overlooking the stream. Toward the bottom of the straightaway, topography dictates that the trail twice crosses the creek. Soon after the second crossing, the trail sidles away from Wilson Creek, leading you onto steep bluffs, where gnarled juniper trees clasp at small soil pockets, and your rocky route switchbacks steeply down among them. You are now staring at the lower reaches of Matterhorn Canyon and soon arrive at the relative flat of the canyon floor.

Here Matterhorn Creek is a meandering stream flowing alternately beside willowed meadows and mixed stands of lodgepole and western white pine. You are initially traipsing well west of the creek, slowly trending closer to the riparian corridor as you continue north. You will find an acceptable tent site just about anywhere you wish along the first mile, up to where the trail strikes east into the meadow and fords the creek. The crossing of Matterhorn Creek is a wade over rounded boulders in all but the lowest of flows and requires caution at peak runoff. Just beyond the ford, you reach a junction where the PCT turns right (south), while left (north) leads up Matterhorn Canyon (Trip 77).

Almost immediately you begin executing more than two dozen often steep switchbacks up a forested slope, gaining more than 1,100 feet by the time you attain a saddle 1.5 miles later. At the gap, there is a worthwhile vista point just north of the trail with views of Matterhorn Canyon and north to the Sawtooth Ridge. Continuing south, you follow a linear passageway, formed along a weakness in the rock. Modest descent leads to shallow Miller Lake (9,446') with tiny campsites along its forested west and north shores. Sitting in a broad, open bowl and ringed by sandy beaches, it is a lovely destination.

PEAK IDENTIFICATION

On the left of gaping Matterhorn Canyon are Doghead and Quarry Peaks and, farther away, some of the peaks of noted Sawtooth Ridge. The great white hulk just to the right of the canyon is multisummited Whorl Mountain, and to its right are the dark gray Twin Peaks, pointy and rusty-colored Virginia Peak, and light gray Stanton Peak.

At Miller Lake, the route makes a hairpin turn and climbs gently to pass a pair of tarns (small campsites), then cuts through a series of gaps between slab ribs. After climbing between a pair of slightly larger domes (good views to the Cathedral Range from the low dome to the southeast), the trail drops to the edge of a broad, early-drying meadow, providing decent campsites, with water always available from a narrow, slab-entrenched lake 0.3 mile to the south. Soon, the trail transports you to a landscape of unusually narrow eroded channels in coarse-crystalled decomposed granite (termed grus) and climbs, yet again, to a forested pass.

HISTORICAL NOTE

This pass was the original route between Spiller Creek and Matterhorn canyons, discovered by Lt. Nathaniel McClure of the Fourth U.S. Cavalry in 1894, during the time when the cavalry were the guardians of the new national park. Most of northern Yosemite’s trail network was laid out during the cavalry years. McClure, Major Harry C. Benson, and others became expert trailblazers, establishing trails to evict shepherds and their sheep from the park. The cavalry patrolled the backcountry until the National Park Service was formed in 1916, and their efforts are today attributed to the survival of the national parks during these first decades.

Eventually you transition to forested switchbacks that carry you to the floor of Spiller Canyon, an 800-foot descent. Once alongside the river, you could head briefly north to off-trail campsites or continue to a large beautiful camping area nestled in a grove of hemlocks just northeast of Spiller Creek’s high-volume crossing (8,772'; 38.00691°N, 119.39036°W).

DAY 7 (Spiller Canyon to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, 9.0 miles): Continuing downstream, the trail slowly diverges from the Spiller Creek drainage and is soon high above the cascading creek on a sandy slope with occasional junipers and expanses of pinemat manzanita. The trail rounds the blunt ridge into the Virginia Canyon drainage and descends a rocky-sandy slope above the valley to meet the trail descending Virginia Canyon (Trip 80); left (northeast) leads up Virginia Canyon, while the PCT, your route, turns right (south).

A view west down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne as you pass Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Within steps you must ford Return Creek, a broad, cobble-and-boulder-bottomed channel that requires extreme caution in early season and may be difficult throughout the summer. If the ford is too intimidating, walk about a quarter mile upstream to find a wider but easier ford—where campsites are nearby in the rocks above—and follow a use trail back downstream to the trail, passing good campsites along Return Creek’s southeastern bank. The trail now hooks south and fords smaller McCabe Creek, a possibly frightening wade itself, for cascades churn just below the crossing. Fill up on water here, for the creeks from here to Glen Aulin dry early.

Once across, the trail begins a steady 600-foot climb up a cool, predominately hemlock-clad slope. The ground is uncharacteristically vegetated, with abundant flowers and even some moss cover. The forest thins near the top of the climb, where slabs again break to the surface and lodgepole pines dominate. A few switchbacks lead to a junction, where left (east) leads to Lower McCabe Lake (Trips 58 and 80), while right (south) is your route to Glen Aulin.

You have now completed the Washboard traverse and begun a long, gentle descent down Cold Canyon—you drop just 400 feet over the next 3.5 miles. In patches of moderate-to-dense forest, enjoy the abounding birdlife (chickadees, juncos, warblers, woodpeckers, robins, and evening grosbeaks). Elsewhere are meadows, where bluebirds and flycatchers flit about, and occasional drier stretches with broken slabs. When there’s water, you can camp in the occasional forest opening or at a meadow edge, but the streams here can be dry by the middle of summer. You enter a particularly beautiful meadow after 3 miles, with some giant boulders along its western edge; like others, it is slowly being encroached on by young lodgepoles.

At the meadow’s southern tip, you climb just briefly, drop steeply back to the river corridor, and continue onward, still mostly through lush lodgepole forest. Wandering fleabane spreads across the forest floor, joined by larkspurs, dwarf bilberry, and one-sided wintergreen. The trail trundles along—this is about as easy as walking gets in Yosemite, with a soft forest floor, gentle grade, and well-maintained trail. About 1.5 miles north of Glen Aulin you emerge from forest cover, crossing more open expanses and descending a bit more steeply. Here are a few possible campsites if there is water in the creek. On the final, rocky downhill to the river, you catch glimpses of Tuolumne Falls and the White Cascade, and their roar carries all the way across the canyon.

Within sight of Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, you reach a junction with the trail that descends the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne (Trip 40) and continuing straight ahead, after 50 feet, you come to a spur trail that goes left to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, crossing Conness Creek on a footbridge. To reach the backpacker’s campground, loop north through the camp, passing the tiny store with its meager supplies, and onward to an open area with many tent sites (7,930'; 37.91051°N, 119.41699°W); there is potable water (when the camp is open), a pit toilet, and animal-proof food-storage boxes. This is the last legal camping before Tuolumne Meadows, so you must camp here or complete the entire Day 8 hike description.

DAY 8 (Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp to Tuolumne Meadows, 5.4 miles): Return to the PCT and cross the Tuolumne River on a bridge just below the roar and foam of stunning White Cascade. During high runoff, you may have to wade on the far side of this bridge—note the expanse of rounded river cobble and boulders strewn across the trail. A brief climb brings you to a trail junction, where you stay left (southeast), signposted to Tuolumne Meadows, while right (southwest) leads to McGee and May Lakes (Trip 51). Returning to the river’s edge, you pass a fine viewpoint of crashing Tuolumne Falls. Beyond, you ascend past wide sheets of clear water spread out on slightly inclined granite slabs and a series of sparkling rapids separated by large pools, the views interrupted by a detour into a moist glen west of the river corridor.

At 1.3 miles above the High Sierra Camp, the trail crosses the river for the last time, again on a footbridge, and climbs a little way above the river gorge. The trail shortly descends to expansive, polished, riverside slabs. For the coming mile, the trail repeatedly dives into a lodgepole glade before emerging back on splendid slabs. Beyond, you come right to the river’s bank at an extremely scenic, wide bend at the edge of a meadow—not yet Tuolumne Meadows—far across which rise granite domes and the peaks of the Cathedral Range. Just ahead, you cross the three branches of Dingley Creek (may be dry by late season). The trail now leaves the river behind for more than two miles, taking a rambling traverse across the landscape along a series of shallow, lodgepole pine–forested depressions, making for easier walking than cutting up and down slab ribs. Soon you meet the trail to Young Lakes (Trip 50; left, north), while you go ahead (right; still southeast) on the PCT, coming close to the northernmost lobe of Tuolumne Meadows before crossing Delaney Creek, a potentially difficult crossing at peak flows.

Just beyond that ford, a spur trail takes off left (east) for Tuolumne Stables, while you veer right (south) to ascend a long, dry, sandy ridge. From the tiny, reed-filled ponds atop this ridge, the trail drops gently to pass near Parsons Memorial Lodge and Soda Springs. After these historic landmarks—both worth a detour if time allows—the PCT picks up a closed dirt road bearing east above the north edge of Tuolumne Meadows and turns left to follow it past interpretive displays to a locked gate (8,590'; 37.87889°N, 119.35854°W). You may have parked a car along the stretch of road between here and Lembert Dome, 0.3 mile ahead.