INFORMATION AND PERMITS: Wilderness permits are required for overnight stays and quotas apply from the last Friday in June through September 15. Fifty percent of permits can be reserved in advance through recreation.gov (search for “Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest Wilderness Permits”), and 50% are available on a first-come, first-served basis at the Bridgeport Ranger District office beginning at 1 p.m. the day before your trip starts. Both reserved and first-come, first-served permits are picked up at the Bridgeport Ranger Station, located at 75694 US 395 at the south end of Bridgeport. If you want the ranger station to leave a reserved permit in their dropbox for you to pick up outside of office hours, call 760-932-7070. Visit tinyurl.com/hooverwildernesspermits.com for more information on reserving permits. Bear canisters are required. Campfires are prohibited above 9,000 feet in the Virginia Lakes and Green Creek basins and above 9,600 feet in Yosemite. Trip 80 enters Yosemite National Park, where pets and firearms are prohibited.

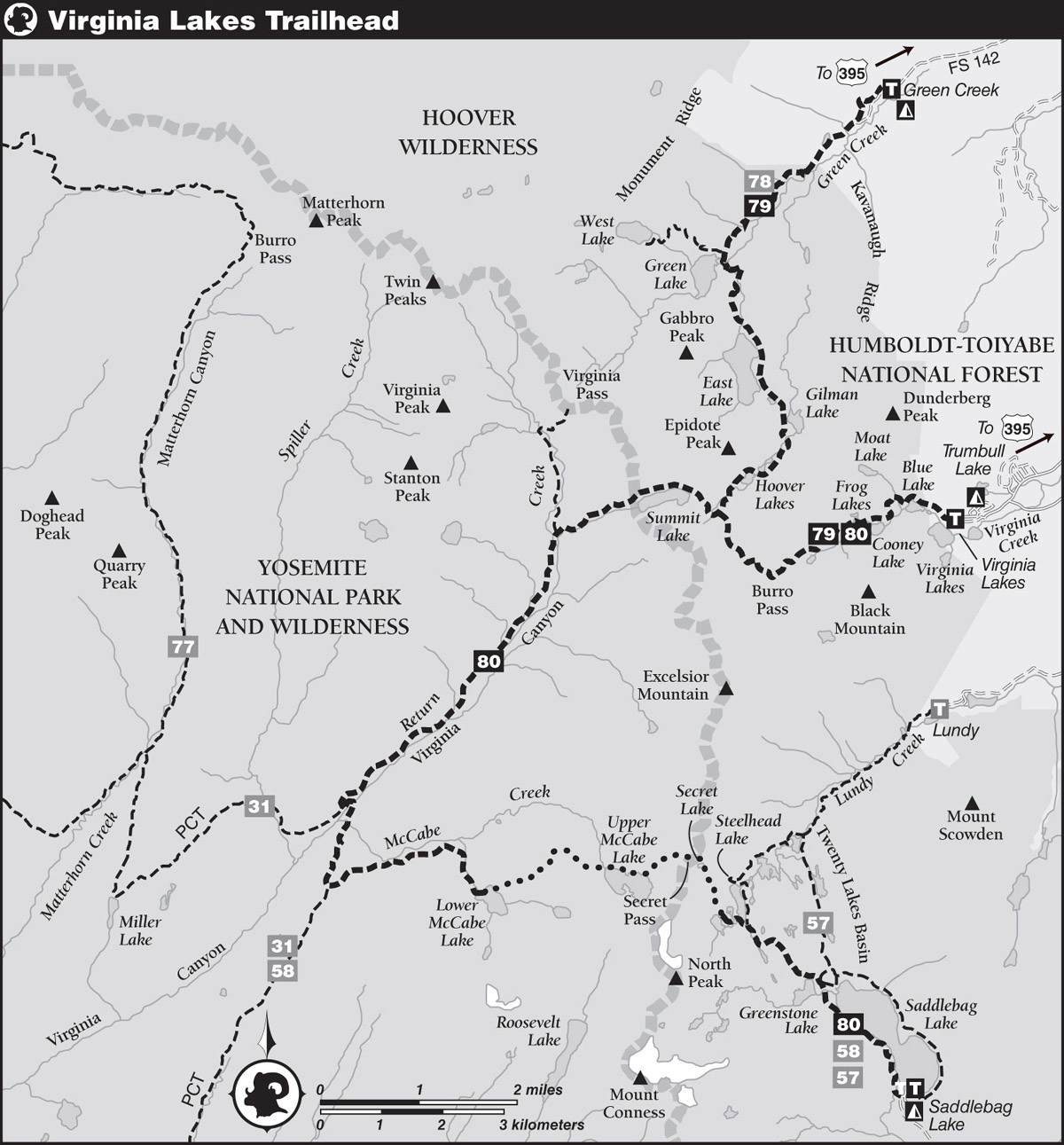

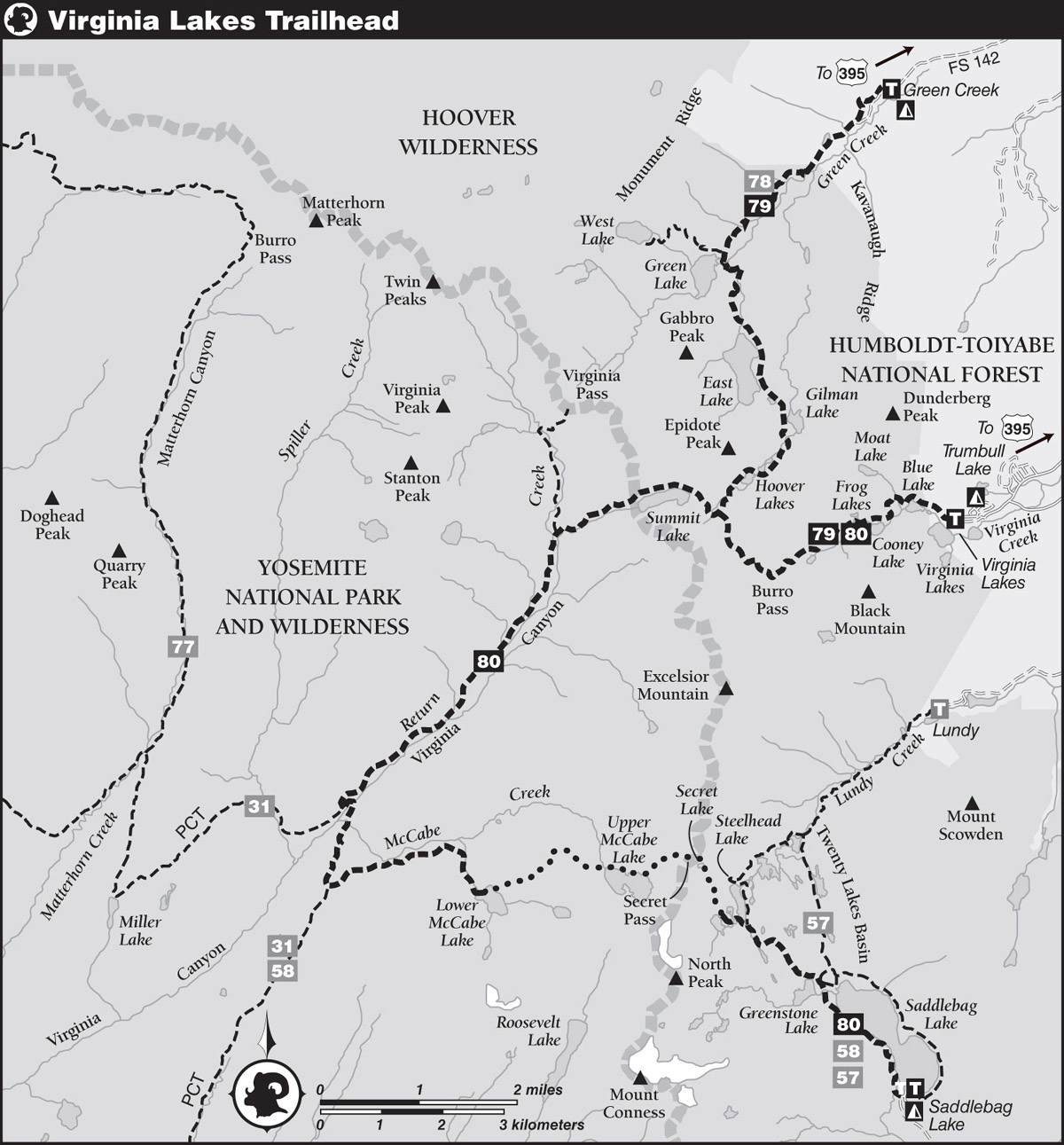

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From Bridgeport, drive south on US 395 through the town to the Bridgeport Ranger Station, near its south edge. Continue 12.1 miles south on US 395 to Conway Summit and the Virginia Lakes Road (Forest Service Road 21) junction. If you’re traveling from the south, Conway Summit lies 12.8 miles north of the CA 120 junction in Lee Vining. Turn west onto Virginia Lakes Road, and follow it 5.1 miles to its terminus, a large dirt parking area with pit toilets. En route you’ll have passed the Virginia Lakes Pack Station on the right, a tract of vacation homes, the Virginia Lakes Resort (with café) on the left, and finally the Trumbull Lake Campground on the right. Just past the campground, the road reverts to gravel. Trumbull Lake Campground has a water faucet, and there are pit toilets at the trailhead.

trip 79 Virginia Lakes and the Green Creek Lakes

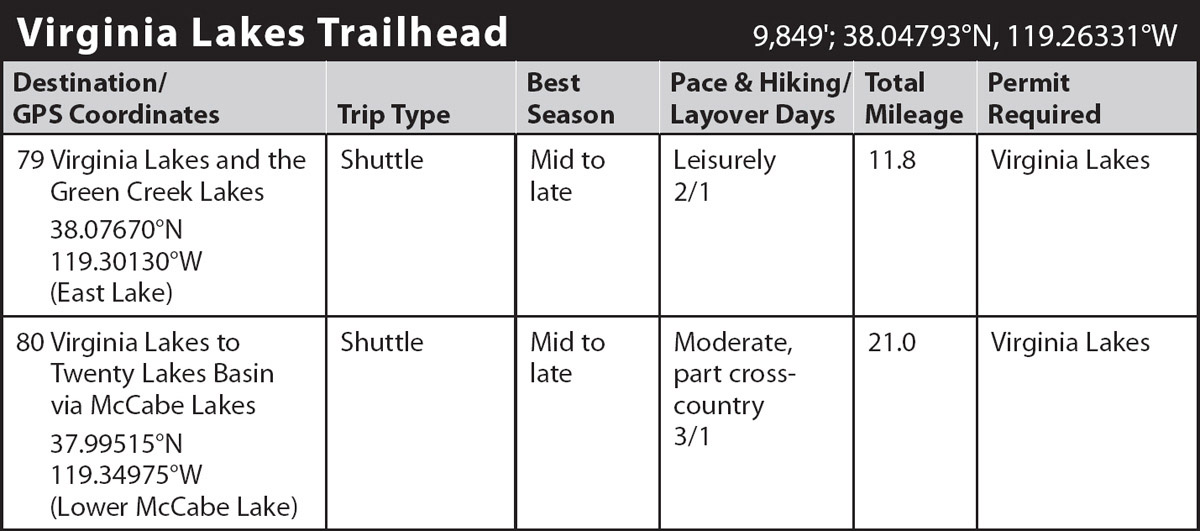

Trip Data: |

38.07670°N, 119.30130°W (East Lake); 11.8 miles; 2/1 days |

Topos: |

Dunderberg Peak |

HIGHLIGHTS: This U-shaped trip circles around Kavanaugh Ridge and Dunderberg Peak, touching the shores of 14 lakes. Scenery along this route is subalpine and alpine, providing a fine sampling of the majestic Sierra Crest. This trip is an excellent choice for a weekend excursion, especially by wildflower enthusiasts and anglers.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: There are two routes between the Virginia Lakes Trailhead and the Green Creek Trailhead, the latter trailhead located along Forest Service Road 142. You can return to US 395 and drive 8.4 miles north to the start of Green Creek Road/FS 142. Take FS 142 3.4 miles to a T-junction with the Dunderberg Meadow Road (FS 20), branch right (north), still on FS 142, and go 5.1 miles to an obvious trailhead parking area, on the right. The second route is to cut between the Virginia Lakes and Green Creek drainages on the Dunderberg Meadow Road: from the Virginia Lakes Trailhead, retrace your steps 1.55 miles down the Virginia Lakes Road, then turn left onto the Dunderberg Meadow Road (FS 20). This dirt road winds 8.5 miles north across the eastern base of Kavanaugh Ridge to the previously noted T-junction with Green Creek Road (FS 142); turn left here and follow the Green Creek Road the final 5.1 miles to the trailhead. Dunderberg Meadow Road is in good condition and much more direct, but both routes take a similar amount of time.

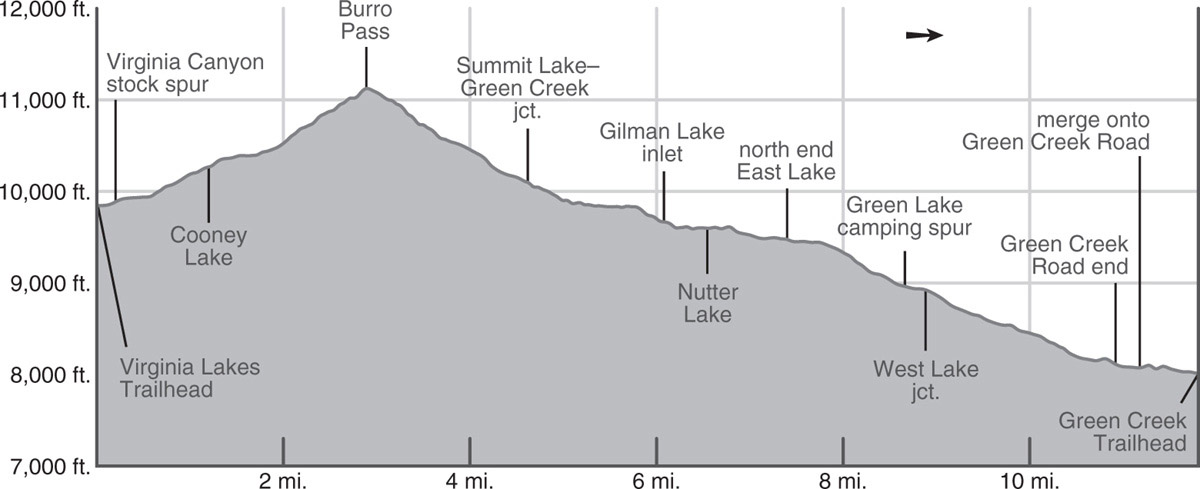

DAY 1 (Virginia Lakes Trailhead to East Lake, 7.0 miles): The trail departs behind the information signs. Numerous use trails around Big Virginia Lake can make it difficult to discern the correct route—once behind the trailhead placard turn right (northwest) and continue not far from the water’s edge until the shoreline bends west. The trail now briefly jogs north, enters a stand of aspens, and curves left again where a horse trail merges from the right (east). Under sparse subalpine shade, your trail quickly passes a tarn and then reaches the Hoover Wilderness boundary. Blue Lake comes into view soon afterward, cupped in steep slopes of ruddy-brown hornfels—a metamorphic rock that doesn’t have layers. In early summer an astonishing diversity of colorful wildflowers emerges from the scant soil covering the rock. You climb gently to moderately across a talus field above the north shore of Blue Lake, while Dunderberg Peak looms to the north.

At Blue Lake’s western headwall, your way climbs steeply, the ascent pausing briefly along the verdant banks of Moat Lake’s merrily descending outlet stream. Now your trail switchbacks more gradually up a forested hillside to reach a small miner’s cabin in a clearing. After another short climb among steep bluffs, you arrive at the outlet of Cooney Lake. As you leave the lake, views open to your trip’s barren high point, Burro Pass (a local name; the pass is unnamed on maps but is also sometimes called Summit Pass or Virginia Lakes Pass), saddling the western horizon.

Beyond Cooney Lake you ascend dry slopes leading to a shelf harboring a clutch of small lakelets—the Frog Lakes—named for once-numerous mountain yellow-legged frogs that have disappeared due to nonnative trout and disease. You cross infant Virginia Creek on rocks and logs, requiring a keen sense of balance (or wet feet) during high flows, and swing south around the meadowy, lowest Frog Lake. Continuing upward on lush alpine turf, you step across the river again and reach the highest lake, where good camps are found among scattered whitebark pines.

You now leave the meadows and lakes behind and diverge north from the creek corridor to climb steadily through a rocky landscape dotted by whitebark pines. Finally, the trail resolves into switchbacks, then leaves the last whitebark pines behind for an alpine ascent along the west wall of a cirque. The relatively warm, mineral-rich, moist metavolcanic soil here supports an abundance of alpine wildflowers rarely seen along a trail. Views across the Virginia Lakes basin continue to improve, then after a burst of short switchbacks—often snow covered through much of July—you gain broad 11,130-foot-high Burro Pass. By walking north just a minute from the trail’s high point, you can also view the Hoover Lakes, at the base of Epidote Peak, and, in the northwest, Summit Lake, at the base of Camiaca Peak.

From the barren, windswept crest, you make an initial descent south, then momentarily switchback northwest. Colorful wildflowers continue to emerge beneath every boulder. Your trail switchbacks northwest down through a small, stark side canyon to a sloping subalpine bench, with small campsites tucked north of the trail. After another set of switchbacks, you arrive at a junction on a small shelf just above East Fork Green Creek, where you turn right (northeast) to head down Green Creek, while left (northwest) leads to Summit Lake (Trip 80).

From the junction, your trail descends northeast past a tarn to an excellent overlook downcanyon to the windswept, largely desolate Hoover Lakes. Beyond, light-colored granitic Kavanaugh Ridge peeks over the massive red shoulder of Dunderberg Peak. Heading north, you descend the bench you’ve been following to the drainage, step across East Fork Green Creek, and cross talus above the west shore of upper Hoover Lake before traversing its north shore. At the northeast corner of upper Hoover Lake, you cross its wide, rocky outlet stream. The trail next follows the east shore of the lower Hoover Lake across a talus slope and then drops easily over willowed benches before crossing the East Fork Green Creek again, this time in a stand of hemlocks and whitebark pines. Less-visited Gilman Lake lies far below at first, the trail eventually coming close to its western shore after passing some small tarns.

Beyond, your route rises gently to cross an expanse of bare rocks, still mostly red metamorphic rock. But you also pass outcrops of conglomerate rocks, easily recognized as a collection of pebbles, cobbles, and boulders cemented together. The trail then follows a shallow trench that leads shortly to small, green Nutter Lake. A short northwest climb from Nutter Lake on a pinemat manzanita–patched slope next presents East Lake, the largest of the Green Creek lakes, spread 100 feet below you under the iron-stained talus skirts of crumbly Epidote Peak, Page Peaks, and Gabbro Peak. The trail parallels the east side of East Lake for most of its 0.75-mile length, passing scattered, usually small campsites to either side of the trail; there are more camping options along the northern half of the shore, where you transition onto granite, offering sandier camping options. The trail soon reaches the north end of East Lake (9,476'; 38.07670°N, 119.30130°W; no campfires). There were once popular campsites here, but most are either too close to water or covered by downed trees; those along the eastern shore are better choices.

Virginia Peak rises steeply in the distance as you descend toward the East Fork of Green Creek. Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

DAY 2 (East Lake to Green Creek Trailhead, 4.8 miles): Just past East Lake, your trail makes the first of three outlet creek crossings, then traipses through flat forest for 0.3-mile (with possible camping to the east), before beginning a 500-foot drop through hemlock-and-lodgepole forest. Soon you reach the second crossing, broad and negotiated on big rock blocks. A short distance later, a third crossing requires much care; there are also rock blocks to step upon, but steep cascades just downstream. After another set of tight switchbacks, the trail levels off. Here you’ll note a spur trail departing left (west) toward Green Lake and its excellent campsites (8,940'). The lake’s relatively large volume and chilly temperatures make it ideal for a good-size trout population, although less appealing for swimming.

Next the trail fords Green Lake’s outlet creek, for hikers best executed on a logjam downstream of the stock crossing. A brief jaunt leads to a junction, where left (west, then northwest) is a trail climbing steeply 1.6 miles up to West Lake, situated in a basin of barren rock. You turn right (northeast) to descend the Green Creek canyon, soon pausing at a rocky knob that provides an unbroken view of the canyon. Next, the trail descends through a swath of luxuriant wildflowers that dazzle the eyes with myriad colors. By early August, the display is diminished, but so is the water flowing down the trail. In fall this stretch of trail is equally showy, as the leaves on the scrubby aspen trees turn a brilliant yellow.

Beyond, you reenter a taller forest dominated by lodgepole pines and aspens; soon descend a dozen short, rocky switchbacks; cross out of Hoover Wilderness; and then traverse along a rocky bench. Below you, tall, stately Jeffrey pines dominate the forest, and you complete your descent with a brief drop to a step-across creek crossing beyond which you reach the dirt Green Creek Road. You follow the road for about 5 minutes before taking a trail branching left (north), which winds and undulates downcanyon, passing above the campground and reaching the parking area at the Green Creek Trailhead. (Note that you could follow the road all the way to the trailhead, and indeed this is the slightly quicker route, but the trail is a much more scenic way to end your excursion.)

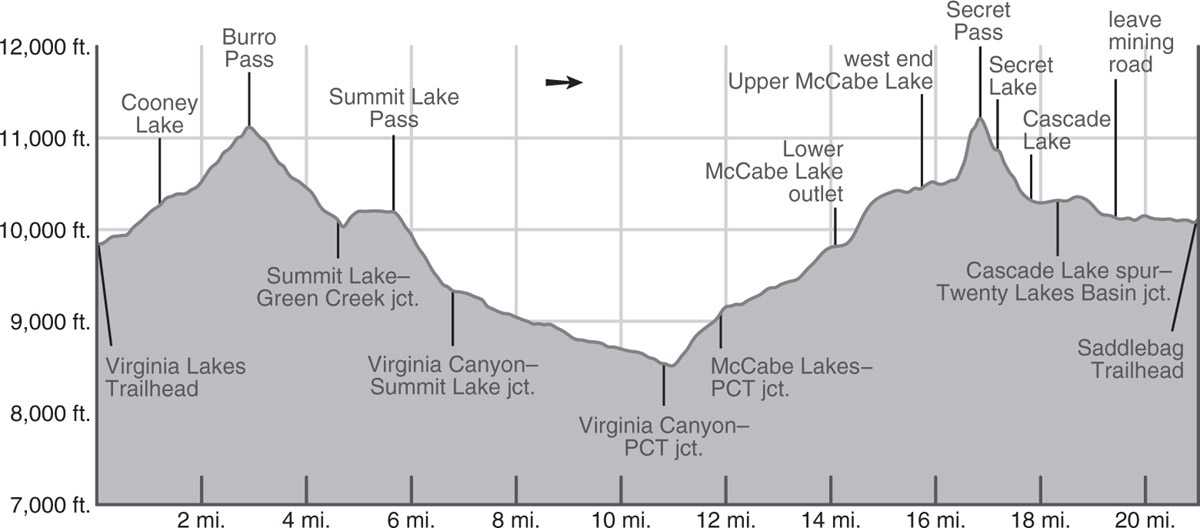

trip 80 Virginia Lakes to Twenty Lakes Basin via McCabe Lakes

Trip Data: |

37.99515°N, 119.34975°W (Lower McCabe Lake); 21.0 miles; 3/1 days |

Topos: |

Dunderberg Peak, Tioga Pass |

HIGHLIGHTS: Much of this scenic route travels through relatively remote sections of northeastern Yosemite National Park that see few visitors. Upper Virginia Canyon and the McCabe Lakes both offer solitude and stunning scenery. This makes a good first off-trail trip, with straightforward navigation and sections with use trails.

HEADS UP! This trip spends both nights in Yosemite National Park. All Yosemite rules and regulations (for example, bear canisters required; pets and firearms prohibited) apply once you cross the park boundary.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: To reach the Saddlebag Trailhead, the trip’s endpoint, from the CA 120–US 395 junction just south of Lee Vining, drive 9.8 miles west on Tioga Road up to the junction with the Saddlebag Lake Road. Turn right (north) and drive 2.4 miles northwest up to Saddlebag Lake on a well-maintained but partially gravel road. Backpackers need to use the lot adjacent to the group campground, reached by making a sharp right just as you pass the dam. There are toilets and water faucets near the backpacker parking area and at the day-use parking lot closer to the water taxi wharf.

DAY 1 (Virginia Lakes Trailhead to Virginia Canyon, 6.8 miles): The trail departs behind the information signs. Numerous use trails around Big Virginia Lake can make it difficult to discern the correct route—once behind the trailhead placard turn right (northwest) and continue not far from the water’s edge until the shoreline bends west. The trail now briefly jogs north, enters a stand of aspens, and curves left (west) again where a horse trail merges from the right (east). Under sparse subalpine shade, your trail quickly passes a tarn and then reaches the Hoover Wilderness boundary. Blue Lake comes into view soon afterward, cupped in steep slopes of ruddy-brown hornfels—a metamorphic rock that doesn’t have layers. In early summer an astonishing diversity of colorful wildflowers emerges from the scant soil covering the rock. You climb gently to moderately across a talus field above the north shore of Blue Lake, while Dunderberg Peak looms to the north.

At Blue Lake’s western headwall, your way climbs steeply, the ascent pausing briefly along the verdant banks of Moat Lake’s merrily descending outlet stream. Now your trail switchbacks more gradually up a forested hillside to reach a small miner’s cabin in a clearing. After another short climb among steep bluffs, you arrive at the outlet of Cooney Lake. As you leave the lake, views open to your trip’s barren high point, Burro Pass (a local name, the pass is unnamed on maps; also sometimes called Summit Pass or Virginia Lakes Pass), saddling the western horizon.

Beyond Cooney Lake you ascend dry slopes leading to a shelf harboring a clutch of small lakelets—the Frog Lakes—named for once-numerous mountain yellow-legged frogs that have disappeared due to disease and nonnative, but tasty, trout. You cross infant Virginia Creek on rocks and logs, requiring a keen sense of balance (or wet feet) during high flows, and swing south around the meadowy, lowest Frog Lake. Continuing upward on lush alpine turf, you step across the river again and reach the highest lake, where good camps are found among scattered whitebark pines.

You now leave the meadows and lakes behind and diverge north from the creek corridor to climb steadily through a rocky landscape dotted by whitebark pines. Finally, the trail resolves into switchbacks, then leaves the last whitebark pines behind for an alpine ascent along the west wall of a cirque. The relatively warm, mineral-rich, moist metavolcanic soil here supports an abundance of alpine wildflowers rarely seen along a trail. Views across the Virginia Lakes basin continue to improve, then after a burst of short switchbacks—often snow covered through much of July—you gain broad 11,130-foot-high Burro Pass. By walking north just a minute from the trail’s high point, you can also view the Hoover Lakes, at the base of Epidote Peak, and, in the northwest, Summit Lake, at the base of Camiaca Peak.

From the barren, windswept crest, you make an initial descent south, then momentarily switchback northwest. Colorful wildflowers continue to emerge beneath every boulder. Your trail switchbacks northwest down through a small, stark side canyon to a sloping subalpine bench, with small campsites tucked north of the trail. After another set of switchbacks, you arrive at a junction on a small shelf just above East Fork Green Creek, where you turn left (northwest), toward Summit Lake, while right (northeast) leads down Green Creek (Trip 79).

From the junction you turn southwest and drop into a seasonally verdant—indeed downright marshy—meadow and cross three broad, shallow, cobble-paved freshets. Just beyond the valley bottom you step across the faster-flowing outlet stream from Summit Lake and begin a short but steep and cobbly ascent, paralleling the outlet stream. Where the climb moderates, you traverse dry sedge flats and benches past some good—but small—hemlock-bower campsites, and soon level off and begin curving west along the north shore of Summit Lake. In midsummer the moist flats you pass through deliver an astonishing burst of color, with dense fields of arnicas and lupines providing foreground for your mountain photos. At the west end of the lake, you reach the Yosemite National Park boundary, barely rising above the 10,195-foot-high lake. Standing at the pass, you are gazing down into remote, lush Virginia Canyon. Staring at the skyline, you can readily identify Virginia Peak, a sharp-pointed metamorphic summit that rises above and north of the summits of Stanton Peak and Gray Butte. A few exposed campsites with spectacular sunset views can be found among clusters of whitebark pines near the pass.

You now drop a rapid 850 feet over the 1.1 miles to the bottom of Virginia Canyon, descending a slope of mixed lodgepole and whitebark pine and enjoying the views up and down Virginia Canyon. The slope is well irrigated and still underlain by metamorphic soils and is correspondingly densely vegetated and colorful. The trail levels out in an equally verdant meadow environment—although a stunning location, the only legal campsites are in trees a short way onward, for almost everywhere is vegetated. You pass a signed junction with a faint trail that turns right (north), climbing up Virginia Canyon (a worthwhile detour for a layover day), and ford Return Creek, the stream draining Virginia Canyon. Just beyond the crossing is a campsite under lodgepole pine cover (9,327'; 38.04670°N, 119.33748°W).

DAY 2 (Virginia Canyon to Lower McCabe Lake, 7.3 miles): The first 4 miles today are a gentle descent down Virginia Canyon, in and out of lodgepole cover. Like most of northern Yosemite’s long, linear, U-shaped canyons, water is abundant on the valley floor, leading to a riot of color well into August. Corn lilies, larkspur, wandering fleabane, primrose monkeyflower, arnicas, violets, and mariposa lilies—to name just a few—all vie for your attention. You regularly step over tributaries draining the slope to the west. One of the most striking aspects of this walk is the many-avalanche-decimated slopes. The canyon walls are steep, granite slabs, just shallow enough to accumulate deep snow that then detaches and flows to the valley floor, taking out the forest en route. Some locations are subjected to such frequent avalanches that only shrubs and scrubby aspen grow, while elsewhere avalanches occur only rarely and mature forests establish—only to be obliterated following a tremendous blizzard. As you continue downward, you pass a selection of small campsites and eventually reach a junction with the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT).

You now turn left (east, then south), signposted for Glen Aulin, while right (west) leads to Benson Pass and Smedberg Lake (Trip 31). Within steps you must ford Return Creek, a broad, cobble- and boulder-bottomed channel that requires extreme caution in early season and may be difficult throughout the summer. If the ford is too intimidating, backtrack about a quarter mile upstream to find a wider but easier ford—where campsites are nearby in the rocks above—and follow a use trail back downstream to the trail. Once across Return Creek, there are some good campsites upstream along its southeastern bank. The trail now hooks south and fords smaller McCabe Creek, a possibly frightening wade itself, for cascades churn just below the crossing.

Once across, the trail begins a steady 600-foot climb up a cool, predominately hemlock-clad slope. The ground is uncharacteristically vegetated, with abundant flowers and even some moss cover. The forest thins near the top of the climb, where slabs again break to the surface and lodgepole pines dominate. A few switchbacks lead to a junction, where you turn left (east), toward the McCabe Lakes, while the PCT continues right (south) down Cold Canyon to Glen Aulin (Trip 31).

Your route continues upward, passing between draws harboring hemlocks and slabbier sections with lodgepoles, western white pines, and the occasional red fir. An ascending traverse takes you into McCabe Creek’s drainage, although the trail remains well south of the creek bank. Your route through here is delightful; a fairyland of twisted lodgepoles and then dense hemlocks with a carpet of colorful flowers underfoot. The grade increases where the trail turns south, following a tributary of McCabe Creek to the lower McCabe Lake. The pleasant streamside walk leads right to the lake’s outlet. Stepping across the creek on logs, the biggest campsite is located east of the outlet under a lovely canopy of lodgepole, hemlock, and even a few whitebark pines (9,820'; 37.99515°N, 119.34975°W; no campfires).

DAY 3 (Lower McCabe Lake to Saddlebag Lake Trailhead, 6.9 miles): Today’s walk begins with 4 off-trail miles, sections of which have decent use trails and elsewhere travelers spread out too much to erode a single route, but only for a short stretch over Secret Pass is the terrain difficult.

Your immediate goal is the upper McCabe Lake, located just over a mile to the east—although you can expect your walking distance to be nearly twice this. From the northeastern corner of Lower McCabe Lake, strike east-northeast up through the forest, aiming for the least steep terrain and staying well north of the inlet creek from the middle McCabe Lake; there is not a use trail for this section. A nearly 600-foot ascent leads to a spectacular high-elevation flat, tarn dotted in all but the driest years—if there are no thunderstorms forecast, this is a delightful, view-rich camp. (You are heading for the northwestern of the two such flats obvious on the USGS 7.5' topo maps; 10,373'; 37.99896°N, 119.33804°W.)

From the flat, continue north, hooking left (north) over a shallow lateral moraine and around a steeper ridge before turning southeast on a gentle sandy slope with boulders. Alpine tundra species, including alpine paintbrush and white mountain heather, continually cheer you onward. A 0.5-mile walk along this slope leads to the upper McCabe Lake outlet. Here a trail suddenly materializes, for everyone follows the same narrow corridor along the lake’s northern shore—you spend the walk staring at the deep, clear, dark-blue waters of this large lake backdropped by steep cliffs to the south. Tiny campsites beneath whitebark pines beckon the true alpinists, until you reach the lake’s northeastern corner and a broad meadow.

Trend northeast across the meadow, taking care to avoid the boggiest bits while aiming for a sand-and-slab slope ahead. At the north end of the meadow, swivel to face due east, pointing just left (north) of steeper rocks. A selection of use trails switchbacks steeply upward, coalescing in a single narrow vegetated chute between steeper bluffs before trending in a more due-easterly direction around 11,000 feet. Here the gradient eases, and you cross sandy alpine tundra toward the ridge’s low point, locally called Secret Pass (11,218'; 37.99967°N, 119.31125°W).

Walking through flower-filled fields around Summit Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Peering over into Twenty Lakes Basin, you can see tiny Secret Lake (unnamed on maps) just 300 feet below you and large Steelhead Lake in the basin, where you will pick up the main trail. There are two commonly used descent routes—if you are comfortable descending some moderately steep slab, starting from Secret Pass, zigzagging straight down and then a little north from the pass is the most direct route to Secret Lake. Others will choose to climb 200 feet up the ridge to the north, toward Shepherd Crest to bypass the steepest terrain, and descend northeast into the open bowl with mine tailing—but note this option can hold late snow in the descent gully. All routes reunite at Secret Lake, where you can pick up a decent use trail near its outlet. (See also the sidebar “Two Ways Up Secret Pass”)

This use trail leads down densely vegetated slopes, crisscrossed by endless rivulets until late in the summer, with flowers absolutely everywhere. Continuing more or less south-southeast, you reach broad, polished slabs between Cascade Lake and the two smaller lakes to the east, so-called Towser Lake to the north and Potter Lake to the south. Passing between Towser and Potter Lakes you then wind down toward Steelhead Lake’s western shore. Follow the shoreline south, cross Potter Lake’s outlet, drop into an incised gulch, and climb briefly to reach the old mining road through Twenty Lakes Basin. Here you turn right (southeast) to complete the final 2.7 miles of your trip, while left (north) continues through Twenty Lakes Basin to Helen Lake (Trip 58).

The road leads southeast, passing a collection of tarns and long, skinny Wasco Lake, before cutting east out of the Mill Creek drainage; the “pass” is almost imperceptible. Dropping again, now in the Lee Vining Creek catchment, you gaze down upon Greenstone Lake and giant Saddlebag Lake. At a junction as you approach Saddlebag Lake you have an option—a water taxi allows a more rapid trip to Saddlebag Lake’s southern end (and the trailhead), but it is often booked out on summer afternoons by day trippers; this is the lefthand (east) branch that continues along the mining road. The trail—now no longer an old road—branches right (south) and continues around the western shore of Saddlebag Lake, first through lush meadows, then across a slope of angular, red talus, leading to the lake’s dam. Recent work has made it safe to cross the dam, and you quickly find yourself walking the last steps up to the Saddlebag Lake Road and Trailhead (10,115'; 37.9657°N, 119.27187°W).