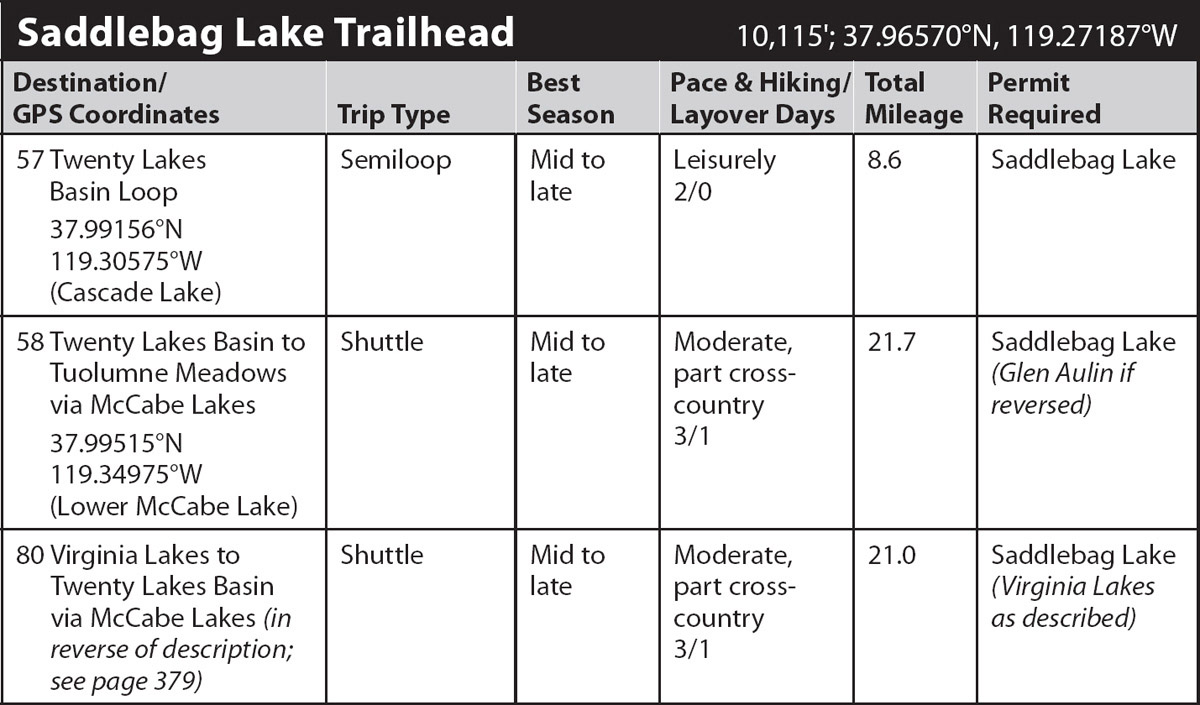

INFORMATION AND PERMITS: Twenty Lakes Basin lies within Inyo National Forest. Wilderness permits are required, but there is no quota. Pick up your permit at the Mono Lake Scenic Area Visitor Center in Lee Vining or at the Tuolumne Meadows Wilderness Center (but not other Yosemite permit-issuing centers). If your trip crosses into Yosemite National Park, all Yosemite rules and regulations apply (for example, bear canisters required; pets and firearms prohibited). Campfires are prohibited throughout the Twenty Lakes Basin and above 9,600 feet in Yosemite.

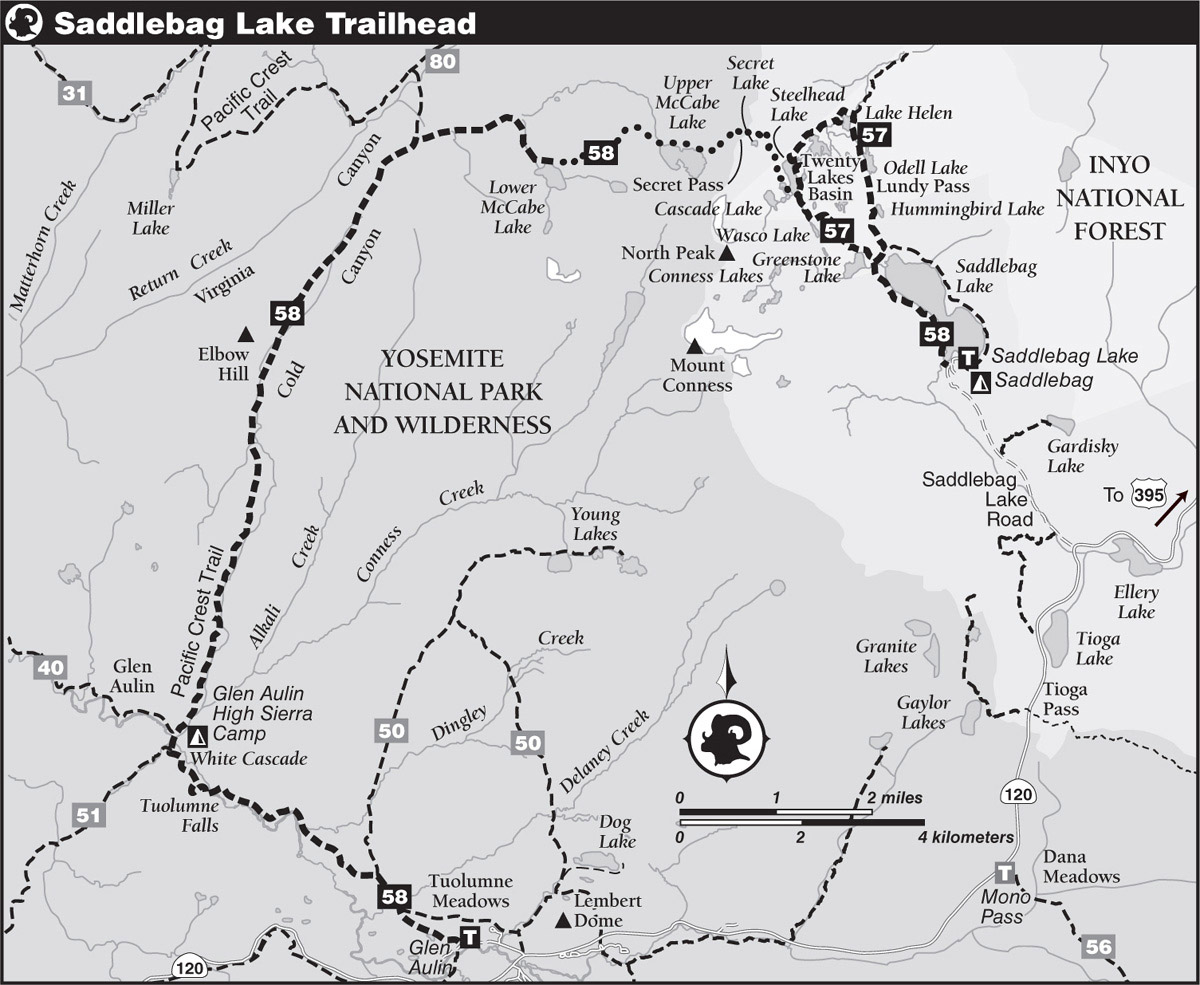

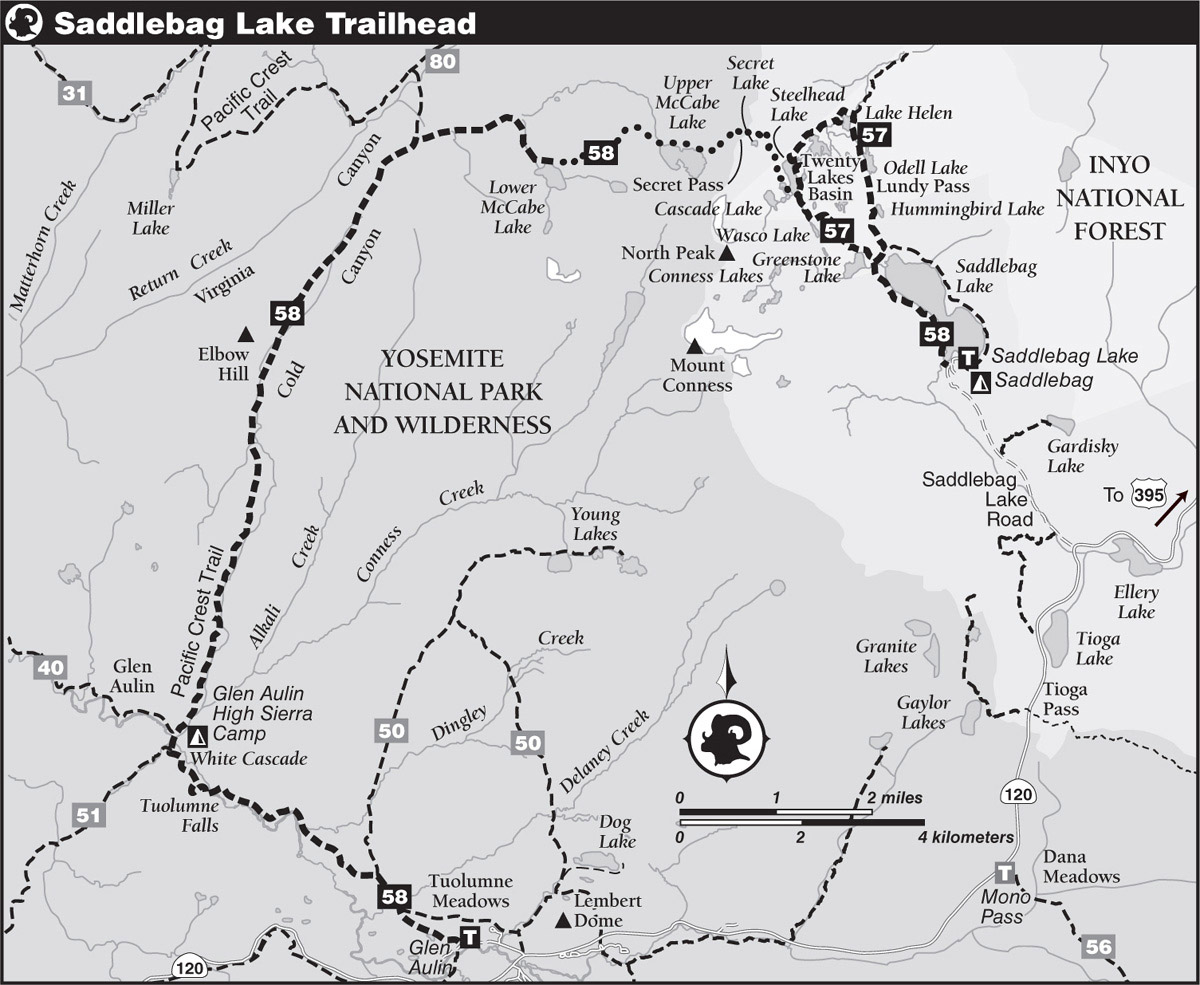

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From Tioga Pass drive 2.1 miles east on Tioga Road (CA 120) down to the Saddlebag Lake junction, located a short distance beyond Tioga Pass Resort. Or, from US 395 just south of Lee Vining, drive 9.8 miles west on Tioga Road up to the junction. From the junction, drive 2.4 miles northwest up to Saddlebag Lake on a well-maintained but partially gravel road. Those on a day hike may park in the lot adjacent to the store (and restaurant), but backpackers need to use the lot in the group campground, reached by making a sharp right just as you pass the dam. There are toilets and water faucets near the backpacker parking area and at the parking lot closer to the store (and water taxi wharf).

trip 57 Twenty Lakes Basin Loop

Trip Data: |

37.99156°N, 119.30575°W (Cascade Lake); 8.6 miles; 2/0 days |

Topos: |

Tioga Pass, Dunderberg Peak |

HIGHLIGHTS: A short jaunt brings backpackers to a scenic granite subbasin for an overnight in the shadow of beautiful peaks. This is the perfect first backpacking trip for young children, with lakes to splash in, granite slabs to play on, and stunning views for the parents. Sturdy day hikers will have no trouble taking this trip in a single day, with or without the ferry’s help.

HEADS UP! Much of Twenty Lakes Basin, which is “carpeted” by shards of the metamorphic rock out of which most of the basin is carved, offers virtually no camping. The granitic subbasin holding Cascade Lake is an exception, although there are also a few campsites around Lake Helen.

HEADS UP! Saddlebag Lake Resort, located at the road’s end, sells fishing licenses if you don’t have one. The resort also offers water taxi service to the lake’s far end, running nonstop all day and shaving 1.5 miles off the hike, each direction; if you wish to use this on the return, book a ticket for a prearranged time before you leave.

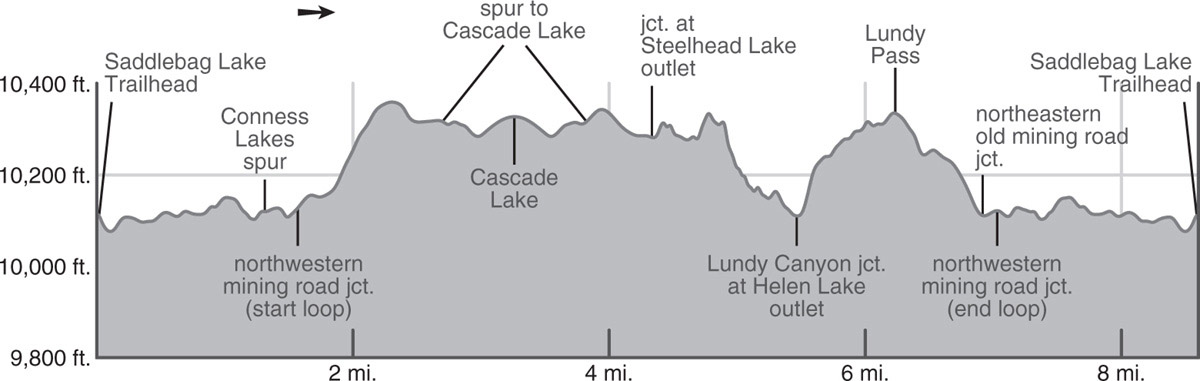

DAY 1 (Saddlebag Lake Trailhead to Cascade Lake, 3.3 miles): To get to the 10,064-foot-high lake’s far end, from the trailhead parking entrance, descend to the east end of the dam and cross on the dam wall. Head across to the trail—a blocky tread cutting across open, equally blocky talus slopes. This metamorphic rock talus may be uncomfortable to walk on, but it creates soils superior to those derived from granitic talus, and hence there is a more luxuriant growth of alpine plants.

About 0.5 mile north of the dam, your trail bends northwest, and Mount Dana, in the southeast, disappears from view. Shepherd Crest, straight ahead across Saddlebag Lake, now captivates your attention. Continuing on and on along the red talus slopes, you reach flatter terrain once you round the end of the ridge. Among willows and a seasonally fiery field of Pierson’s paintbrush, you pass an unsigned spur trail that leads left to the nearby south shore of 10,143-foot-high Greenstone Lake and beyond to the Conness Lakes. Continuing straight ahead (right; north) you soon reach the north end of Saddlebag Lake and quickly meet a closed mining road; those who chose to take the ferry across, join the route at this point, merging from the right (east).

Turning left (northwest) onto the old road, you climb gently, staring southwest across Greenstone Lake to the granite wall sweeping up to a crest at Mount Conness and sharp-tipped North Peak. The northwest shore of Greenstone Lake sports many camping options, but camping is prohibited on the lake’s southern shore as well as upstream toward the Conness Lakes. Your tread climbs northwest, then, nearly imperceptibly, crosses a drainage divide. You are now in the drainage of northeast-flowing Mill Creek—that was probably the easiest pass you have ever ascended! The trail then descends slightly to relatively warm Wasco Lake and a string of tarns often filled with western tree frog tadpoles.

Just past the second tarn a use trail drops into the small entrenched drainage to your left (west) and follows it toward Steelhead Lake’s southern tip. It then skirts Steelhead Lake’s western shore just long enough to cross an inlet creek and pass the first small lake, colloquially Potter Lake. Then you head briefly west between Potter Lake and Towser Lake (the northern of the unnamed lakes between Cascade and Steelhead Lakes), toward Cascade Lake. From here, trend west and north and pick a campsite that suits you in the Cascade Lake environs—there are many sandy patches among the never-ending slabs in this treeless basin (10,335'; 37.99156°N, 119.30575°W; no campfires). A layover day offers fine off-trail exploring and fishing for golden trout.

DAY 2 (Cascade Lake to Saddlebag Lake Trailhead, 5.3 miles): The remaining loop is much harder going than simply retracing your steps, but assuming you are completing the loop, return to the main trail near Steelhead Lake and follow the former road north alongside the deep lake to its outlet. Diverse and colorful flowers—several species of penstemon, straggly yellow arnicas, and burgundy-colored roseroot—decorate the sandy slopes on either side of the trail. Just before reaching the outlet stream, the old road turns sharply left (west), crossing the creek west of your route, then continuing northwest above the lake’s north shore to the Hess Mine. This mine, like others nearby, lies near the contact between rock types, for that is where ore is most likely to be found. Looking at the panorama of peaks you immediately see the distinction in landscape between the sharp-pointed granitic peaks to the west and the more rounded metamorphic summits to the east. You continue straight ahead, north.

As you cross Steelhead Lake’s outlet, Mill Creek, you are embarking on a route that follows a narrow use trail that is generally very obvious, but there are a few places where it becomes faint or steep. You head downstream, scramble over a low knoll, and quickly descend to the west shore of tiny Excelsior Lake, unnamed on most maps. At the north end of Excelsior Lake, you go through a notch just west of a low metamorphic rock knoll that is strewn with granitic glacial erratics, boulders dropped by melting glaciers. A long, narrow pond comes quickly into view. Your trail skirts its west shore, then swings east to the west shore of adjacent, many-armed Shamrock Lake.

North Peak rises above Greenstone Lake. Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Your ducked (marked with cairns) route—more cross-country than trail along this section—crosses an easily navigated talus fan along Shamrock Lake’s northern shore, continues northeast over a low ridge, then descends steep slabs and bluffs to reunite with Mill Creek on flatter terrain. You traipse past two ponds and reach the west shore of Lake Helen, sporting some small campsites beneath whitebark pines. Encircling the lake’s north shore on a good trail through dark talus, you loop down to cross Mill Creek on a log or rocks. A step beyond the crossing is a junction: your route is to the right (south) toward Lundy Pass and Odell Lake, while the left branch (northeast) is a rough trail descending to Lundy Canyon.

Heading south, the trail becomes better again, as you skirt the eastern shore of Lake Helen on red scree, then follow an inlet stream upward through a straight, narrow gully that transforms into a wildflower garden as soon as the late-lasting snow melts; the columbines are particularly showy here. The trail continues alongside the remarkably straight channel until you climb above the creek’s western bank and soon approach Odell Lake. Climbing gently above the lake’s west shore, you parallel it southward. You then continue the most gradual of climbs to reach Lundy Pass, which drops you back into the Lee Vining Creek drainage and on toward Hummingbird Lake, boasting terrific lakeshore for an afternoon break. Beyond, the trail reaches a four-way junction where you again intersect the old mining road. Turn right (west) to retrace your steps around Saddlebag Lake’s western shore or head straight ahead (south) to the water taxi dock. You can also turn left to follow the old road around Saddlebag’s eastern shore, a slightly longer choice.

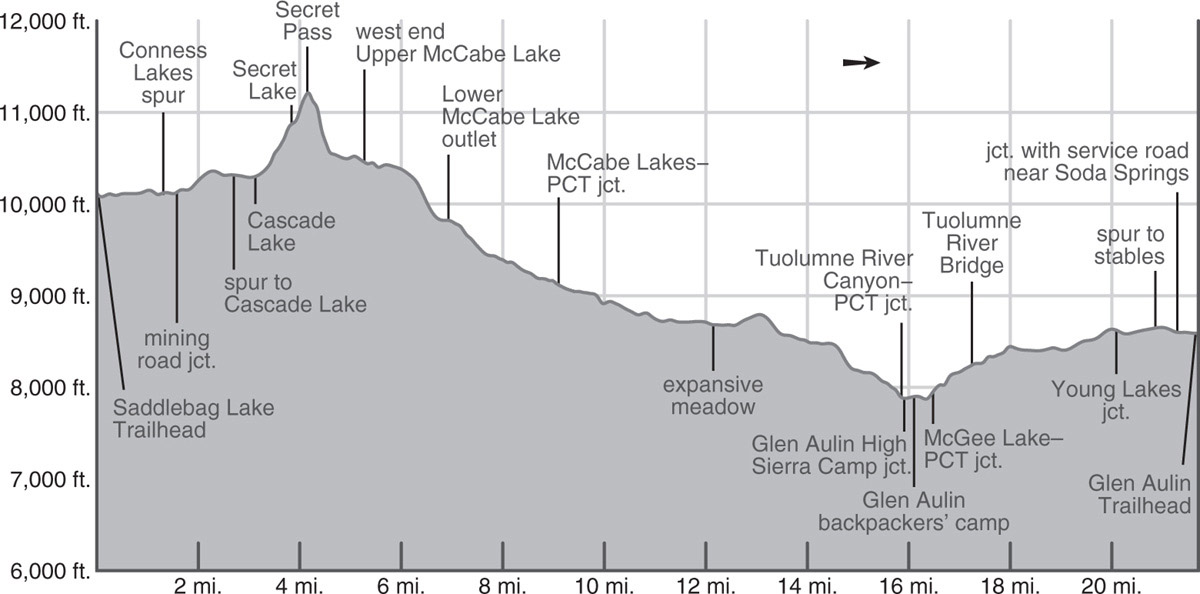

trip 58 Twenty Lakes Basin to Tuolumne Meadows via McCabe Lakes

Trip Data: |

37.99515°N, 119.34975°W (Lower McCabe Lake); 21.7 miles; 3/1 days |

Topos: |

Tioga Pass, Dunderberg Peak (barely), Falls Ridge |

HIGHLIGHTS: This adventurous cross-country trek climbs out of Twenty Lakes Basin and into Yosemite near the lightly visited McCabe Lakes. Breathtaking views and alpine scenery await you. Beyond Lower McCabe Lake, the route merges with the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT) and heads for Tuolumne Meadows via Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp.

HEADS UP! This trip is only for those experienced in cross-country travel and navigation.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: Your endpoint is in Tuolumne Meadows, just off Tioga Road (CA 120), along a dirt road extending from the Lembert Dome parking area to the Tuolumne Meadows Stables. From here, regain Tioga Road and drive 9.1 miles northeast along Tioga Road, crossing Tioga Pass and descending to the Saddlebag Lake turnoff.

DAY 1 (Saddlebag Lake Trailhead to Lower McCabe Lake, 6.9 miles, part cross-country): To get to the 10,064-foot-high lake’s far end, from the trailhead parking entrance, descend to the east end of the dam and cross on the dam wall. Head across to the trail—a blocky tread cutting across open, equally blocky talus slopes. This metamorphic rock talus may be uncomfortable to walk on, but it creates soils superior to those derived from granitic talus, and hence there is a more luxuriant growth of alpine plants.

About 0.5 mile north of the dam, your trail bends northwest, and Mount Dana, in the southeast, disappears from view. Shepherd Crest, straight ahead across Saddlebag Lake, now captivates your attention. Continuing on and on along the red talus slopes, you reach flatter terrain once you round the end of the ridge. Among willows and a seasonally fiery field of Pierson’s paintbrush, you pass an unsigned spur trail that leads left to the nearby south shore of 10,143-foot-high Greenstone Lake and beyond to the Conness Lakes. Continuing straight ahead (right; north) you soon reach the north end of Saddlebag Lake and quickly meet a closed mining road; those who chose to take the ferry across join the route at this point, merging from the right (east).

Campsite on a perch near Upper McCabe Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Turning left (northwest) onto the old road, you climb gently, staring southwest across Greenstone Lake to the granite wall sweeping up to a crest at Mount Conness and sharp-tipped North Peak. The northwest shore of Greenstone Lake sports many camping options, but camping is prohibited on the lake’s southern shore as well as upstream toward the Conness Lakes. Your tread climbs northwest, then, nearly imperceptibly, crosses a drainage divide. You are now in the drainage of northeast-flowing Mill Creek—that was probably the easiest pass you have ever ascended! The trail then descends slightly to relatively warm Wasco Lake and a string of tarns often filled with western tree frog tadpoles.

Just past the second tarn a use trail drops into the small entrenched drainage to your left (west) and follows it toward Steelhead Lake’s southern tip. It then skirts Steelhead Lake’s western shore just long enough to cross an inlet creek and pass the first small lake, colloquially Potter Lake. Then you head briefly west between Potter Lake and Towser Lake (the northern of the unnamed lakes between Cascade and Steelhead Lakes), toward Cascade Lake. At this point the well-established use trail fades and the cross-country route begins. There are minor use trails for much of the distance between here and Lower McCabe Lake, but don’t depend upon finding them for navigation.

As you approach Cascade Lake, begin heading in a north-northeasterly direction toward the low point in the steep headwall separating North Peak and Shepherd Crest. Your first goal is to get to a small lake perched just below where the wall becomes steepest, unofficially called Secret Lake. Near a tiny, unmapped, flower-lined inlet to Cascade Lake (10,355'; 37.99210°N, 119.30604°W) you should find a good use trail to Secret Lake; locating this trail from the start will save you time and effort on the ascent—and it is the environmentally conscious choice, for otherwise you incessantly trample delicate alpine vegetation.

Pause at Secret Lake to study your choices for the next section of the route and pick the one that best suits you; we offer two suggestions in the sidebar “Two Ways Up Secret Pass”. Whichever route you take—and that depends on your skillset and the amount of snow present—your next goal is to get to Secret Pass (11,218'), the low point on the ridge.

TWO WAYS UP SECRET PASS

Here are two suggestions for getting to Secret Pass, the low point atop Shepherd Crest:

1. Most people choose this way, especially on the way up: From the south side of Secret Lake, walk directly up the increasingly steep wall until, about halfway up, at just over 11,000 feet, you come to a long ledge that slopes slightly up to the south. Follow this ledge for about 250 feet south, then leave it to zigzag almost directly up steep slabs, ending up near the ridge’s low point, Secret Pass (11,218').

2. Hikers who want to put out some extra effort to achieve certainty and avoid steep exposure can pick their way up the blue-gray scree-laden stripe on the wall north of Secret Lake to the lip of what looks like a lake basin, but is simply a giant talus field. From there, traverse slightly upward to the right (northeast), diagonalling up to the crest in a loose scree gully. You reach the main ridge of Shepherd Crest near the uppermost whitebark pines, almost 250 feet above Secret Pass and head south back to the pass. Note this route lacks exposure but holds snow later into the summer.

Once you’re on Secret Pass (11,218'; 37.99967°N, 119.31125°W), you need to make your way down to Upper McCabe Lake. You initially stick to broken slabs on the south side of the broad drainage, trending into a narrow vegetated gully just under 11,000 feet. While this upper section has stretches of use trail, you are unlikely to follow it continually—just make tight switchbacks as you pick your way down sandy ramps between short, steep outcrops.

By 10,700 feet you are below the slabs on a sandy slope—now the use trail should be obvious again and you follow it to flatter ground, skirting the east side of a marshy meadow until you approach Upper McCabe Lake. Follow the lake’s north shore, passing some tiny campsites nestled among whitebark pines with astonishing views of the surrounding ridges. At Upper McCabe Lake’s northwest corner cross nascent McCabe Creek, then strike out for the low saddle due west of the outlet and about 0.3 mile away; do not follow McCabe Creek downward. Cairns may be present to guide you, but expect to have to navigate by map and compass (or GPS).

Beyond this saddle (10,411'; 38.00071°N, 119.33633°W), the best route heads generally west-southwest, remaining north of and well above Middle McCabe Lake. It then drops past snowmelt tarns (and beautiful open campsites) not shown on the topo map and winds down through forest cover to the east shore of Lower McCabe Lake. The biggest campsites (9,820'; 37.99515°N, 119.34975°W; no campfires) are just before you cross Lower McCabe Lake’s outlet creek. Fishing for brook trout is excellent.

DAY 2 (Lower McCabe Lake to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, 9.4 miles): In late season or during a drier summer, be sure to get water at Lower McCabe Lake or its outlet stream, as this may be your last chance before Glen Aulin—the creek down Cold Canyon can dry up. Crossing Lower McCabe Lake’s outlet creek, you pick up a true trail and follow it northwest, then west, mostly beside the creek. For long stretches it is a beautiful, lush forest, at first dense with diminutive hemlocks, then a fairyland of twisted lodgepoles, with a carpet of colorful flowers underfoot. A little farther along you enter a more open forest of lodgepole, hemlocks, western white pine, and occasional red fir. Veering away from the creek, the trail crosses more open terrain, then back in forest, drops more steeply to a junction with the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), where you turn left (south), toward Glen Aulin, while right (north) is the PCT’s route toward Sonora Pass (Trip 31).

Now begins a long, gentle descent down Cold Canyon—you drop just 400 feet over the next 3.5 miles. In patches of moderate to dense forest enjoy the abounding birdlife (chickadees, juncos, warblers, woodpeckers, robins, evening grosbeaks). Elsewhere are meadows, where bluebirds and flycatchers flit about, and occasional drier stretches with broken slabs. When there’s water, you may also be able to camp in the occasional dry, forested patch or at a meadow edge, but the streams can be dry by the middle of summer. You enter a particularly beautiful meadow after 3 miles, with some giant boulders along its western edge that is slowly being encroached upon by young lodgepoles.

At the meadow’s southern tip, you climb just briefly, drop a bit more steeply back to the river corridor, and continue onward, still mostly through lush lodgepole forest. Wandering fleabane spreads across the forest floor, joined by larkspurs, dwarf bilberry, and one-sided wintergreen. The trail trundles along—this is about as easy as walking gets in Yosemite, with a soft forest floor, gentle grade, and well-maintained trail. About 1.5 miles north of Glen Aulin you emerge from forest cover, crossing more open expanses and descending a bit more steeply. Here are a few possible campsites if there is water in the creek. On the final, rocky downhill to the river, you catch glimpses of Tuolumne Falls and the White Cascade, and their roar carries all the way across the canyon.

Within sight of Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, you reach a junction with the trail that descends the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne (right; west; Trip 40) and continuing straight ahead (left; northeast), after 50 feet, come to a spur trail that goes left (east) to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, crossing Conness Creek on a footbridge. To reach the backpackers’ campground, loop north through the camp, passing the tiny store with its meager supplies, and continue to an open area with many tent sites (7,930'; 37.91051°N, 119.41699°W); there is potable water (when the camp is open), a pit toilet, and animal-proof food-storage boxes. This is the last legal camping before Tuolumne Meadows, so you must camp here or complete the entire Day 3 hike description.

DAY 3 (Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp to Tuolumne Meadows, 5.4 miles): Follow Trip 31, Day 8 to the Glen Aulin Trailhead (8,590'; 37.87889°N, 119.35854°W).

Tarns near Upper McCabe Lake Photo by Elizabeth Wenk