INFORMATION AND PERMITS: This trip is in Yosemite National Park: wilderness permits and bear canisters are required; pets and firearms are prohibited. Quotas apply, with 60% of permits reservable online up to 24 weeks in advance and 40% available first-come, first-served starting at 11 a.m. the day before your trip’s start date. Fires are prohibited above 9,600 feet. See nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wildpermits.htm for more details.

DRIVING DIRECTIONS: From the Tioga Road–Big Oak Flat Road junction in Crane Flat, drive northeast 14.5 miles east along Tioga Road (CA 120) to the White Wolf Lodge turnoff. Follow White Wolf Road 1.1 miles to the trailhead parking area, located on the right, just before the entrance to White Wolf Campground. If you are traveling from the east, take Tioga Road 24.8 miles west from the Tuolumne Meadows Store to the White Wolf Road junction. In early summer, White Wolf Road is often closed, adding 1.1 miles to your hike; there is limited parking at the junction alongside Tioga Road.

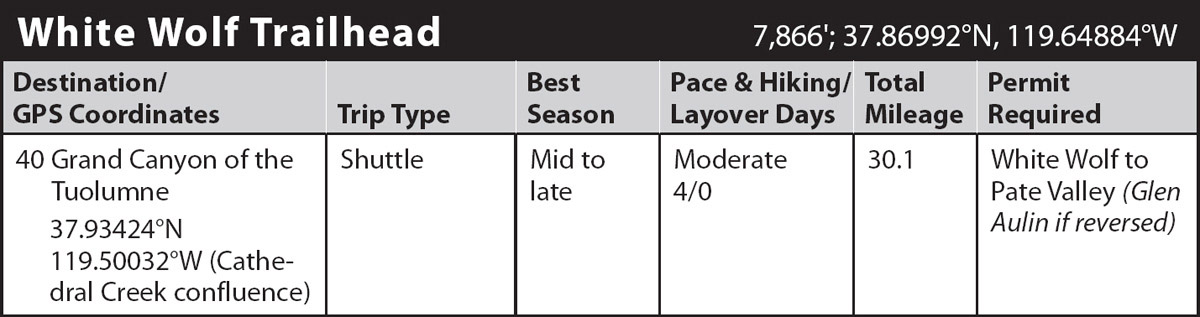

trip 40 Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne

Trip Data: |

37.93424°N, 119.50032°W (Cathedral Creek confluence); 30.1 miles; 4/0 days |

Topos: |

Tamarack Flat, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, Ten Lakes, Falls Ridge, Tioga Pass |

HIGHLIGHTS: In taking this trip, you’ll experience firsthand what the mighty Tuolumne River and its Pleistocene glacier have created over tens of millions of years—and the water continues to create today. If you have only a couple of days, an out-and-back trip based on Day 1 of this trip, as far as Morrison Creek, makes an easy weekender with a fine view of the Tuolumne River Canyon.

HEADS UP! If the preceding winter was a heavy one, this trip may be hazardous in early season because of high water and hazardous at any time if needed bridges have been swept away by high runoff—a remarkably regular occurrence along this route.

HEADS UP! YARTS provides daily shuttle services between White Wolf and the Tuolumne Meadows Store. Although not required it is best to make reservations in advance. And certainly check the time table to time your exit—or best of all, see if it works to leave a car where you finish the walk and take the shuttle to the trailhead the morning of your trip, eliminating the need to precisely time your exit.

SHUTTLE DIRECTIONS: Your trip ends at the Lembert Dome parking area in Tuolumne Meadows, 25.1 miles east along Tioga Road (CA 120) from the White Wolf Road. You can shuttle a car or use the local transit system, YARTS, to return to your car at White Wolf Lodge.

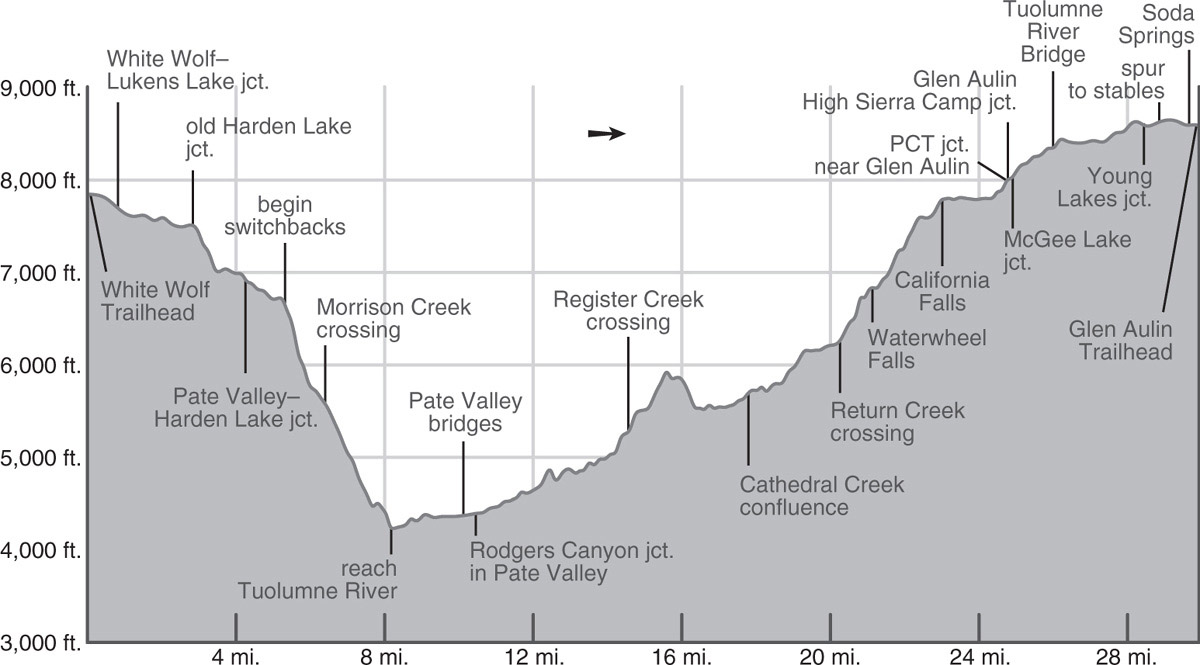

DAY 1 (White Wolf Trailhead to Pate Valley, 10.1 miles): The described trailhead is approximately opposite White Wolf Lodge and just south of the White Wolf Campground entrance road, not along the service road, although you could follow the service road and link back to the described route beyond Harden Lake. The trail begins by skirting the south side of the campground through a flat, lush lodgepole pine forest, continuing much the same to the seasonal Middle Tuolumne River. At full flow it is crossed via a log or sandy-bottomed wade. A few steps farther lead to a signed junction, where you turn left (northwest) toward Pate Valley, while right (south) leads to Lukens Lake. The trail strikes north across rolling uplands to cross a nearly imperceptible ridge. Then descending, the trail follows a lovely creek to a beautiful, forest-fringed meadow dense with flowers until midsummer. Beyond, the route climbs gently for an easy mile to a more open, distinctive ridgetop. Here, you stand on the crest of a moraine that was deposited by a glacier that once flowed down the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne—and therefore impressively marks the height to which ice filled the valley.

Two long switchbacks take you down to a sandy flat with an easily missed, abandoned and unsigned lateral left (west) to Harden Lake, while you continue ahead (right; north-northeast). At first you cannot see the Tuolumne River Canyon, as the trail crosses several more lateral-moraine crests, but after the grade steepens and you descend on switchbacks sparser forest cover permits your first views across the canyon. Just under a mile of switchbacks leads to another junction, 4.3 miles from the trailhead, where left (west) leads again to Harden Lake and you turn right (east) to Pate Valley. Since your descent followed a bedrock rib, you may not have noticed the verdant slopes left and right of you, rich with flowers and thickets of quaking aspen due to abundant moisture. Water collects in the moraine sediments each winter and spring, slowly oozing out during the summer months and irrigating the hillside.

The trail takes you northeast, winding across slabs and seeps, through pocket meadows, and stepping across many small rivulets draining the slopes above. As you cross one particularly densely forested bench, you can suddenly hear Morrison Creek to the right and cross a tributary on a plank bridge. A little beyond, the forest cover opens, and just south of the trail, on a bedrock granite ridge is a choice break spot (and possible campsite) to enjoy the view north across the canyon to broad Rancheria Mountain. The trail now begins the final plunge to the bottom of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne, still more than 2,000 feet below.

At first, the trail descends steeply on tight, gorgeously constructed switchbacks through the narrow gully that holds Morrison Creek; white fir, incense cedar, sugar pine, and dogwood provide shade. After dropping about 700 feet, the trail leaves the sheltered draw for open slab and views open up dramatically as you traverse north, then east. You cross a bench where you should stop for breathtaking views of this phenomenal canyon, including Hetch Hetchy Reservoir and Rancheria Mountain. There are splendid campsites here as long as Morrison Creek flows (usually through midsummer, but note the flatter stretch of stream near the bench dries out before the steeper sections of creek just 0.1 mile upstream or downstream). Passing another stretch of slab with more camping, you cross Morrison Creek, now shaded by incense cedars, black oaks, and canyon live oaks.

The last 1,200 feet to Pate Valley are mostly across exposed slopes on a steep, in part, cobblestoned trail. Along this magnificent descent you can see and hear the Tuolumne River far below. At an elevation of 5,000 feet, the trail crosses an unmapped seasonal creek channel, doubling as an avalanche chute in the winter. Four hundred feet lower, you cross another mapped seasonal creek. Both of these creeks can be dangerous torrents when runoff is high. At 4,400 feet, the grade levels briefly, and you pass a moraine-dammed seasonal pond before entering tall forest again. Another 200-foot descent brings you to the canyon floor at the western end of Pate Valley.

Here you first encounter campsites on a bench high above the river, under incense cedar shade. If you’d like to camp in grander forest, continue upcanyon; the walking is easy. For the first mile, you are crossing a steep slope without campsites, but thereafter traverse a broad bench. The popular Pate Valley campsites are at the eastern end of this valley, just before the first bridge over the river in a cathedral forest of tall incense cedars, white firs, and ponderosa pines (4,395'; 37.93111°N, 119.59435°W). There are additional campsites on the north side of the river, downstream of the crossing.

DAY 2 (Pate Valley to Cathedral Creek confluence, 7.8 miles): Today’s journey takes you through the narrowest and deepest part of the Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne. The trail crosses a pair of bridges, the first over an overflow channel that dries late season, and the second across the main river channel. Once north of the river, you enter a broad flat valley with a densely vegetated wet understory and abundant downed logs from a collection of fires. Surrounded by wildflowers and miniature wild strawberries you come to a junction with the trail that leads left (north) to Pleasant Valley and Rodgers Canyon, while you turn right (east), toward Glen Aulin, passing through a narrow marshy corridor.

WHY THE MARSH?

Perhaps bedrock, acting like an underground dam, has forced groundwater near the surface here to produce a lush, muddy area. Though it’s too wet for trees, many species of water-loving flowers and shrubs thrive here, including cow parsnip and rushes.

Beyond, you cross a sandy flat, then where a granite bluff extends right to the river’s edge and the trail is just inches from the flow, you cross a short section of cobblestones set in cement to withstand flooding. If there is water over the trail and you find it unsafe, turn back.

A gentle ascent brings you to another burned area, this one dating to 1985, where the lack of tall trees tells you the fire was quite hot. Just beyond this area you leave the flat river terrace you’ve been following and come to some fantastically large and deep pools in the bedrock—a fine swimming and fishing spot in late summer. Now 1.4 miles beyond the last junction, the canyon narrows, and the trail stays close to the river. Over the next 1.3 miles there are both spots where you may have to wade during high water and locations where the trail is routed high above the riverbank to avoid the flow.

Next you enter a wider, sunnier valley—another river terrace, composed of sediment deposited in long-ago floods. Be advised: The Grand Canyon of the Tuolumne has a well-earned reputation for having a large population of reptiles, including the ubiquitous blue-bellied western fence lizards, alligator lizards, and quite a few rattlesnakes. Look carefully before stepping over logs or taking a break on a sunny rock. Soon the landscape again pinches closed and you walk gradually along narrower terraces and across slab, passing occasional small campsites and enticing swimming holes.

The canyon closes in further as you approach Muir Gorge. Named after John Muir, a man who eagerly sought out inaccessible places, Muir Gorge is the only part of the canyon whose walls are too steep for a trail, so you’re obliged to climb around it. Beyond two live oak–shaded campsites, the trail turns north and begins climbing away from the river; at one point you can look straight up the dark chasm of Muir Gorge.

In an alcove, the trail crosses Rodgers Canyon’s creek on a bridge, then wades adjacent Register Creek, difficult at high flows. You have now covered 4.6 miles for the day—this terrain is not for fast walking! Tight, shaded switchbacks ascend the side canyon of Register Creek before the trail trends southeast across a sandy passageway between slabs. After a short descent, you switchback up another 500 feet to top a granite spur overlooking the river—it is well worth a short detour south for a better peek into mysterious Muir Gorge.

Cutting across granite slabs and through forested draws, the trail descends back to the river above Muir Gorge where the canyon again widens. In another quarter mile, you come to a seasonal stream channel in white gravel. Between the trail and the river there’s an excellent campsite—the first of many good choices over the next gentle 1.2 miles. Soon Cathedral Creek, spilling down the canyon’s southern wall will catch your attention. The river jogs a little south at the confluence and here, on a knob overlooking the Tuolumne River and staring straight at Cathedral Creek are some more good campsites (5,654'; 37.93424°N, 119.50032°W).

DAY 3 (Cathedral Creek confluence to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp, 6.8 miles): You begin today with a steady 1.6-mile ascent, soon entering landscape burned in the 2009 Wildcat Fire, making most of the previously popular campsites below the Return Creek confluence less appealing. At 2.5 miles into your day, a bridge takes you across Return Creek, and now the real climbing—and falls—begin.

Tuolumne River Photo by Elizabeth Wenk

Waterwheel Falls looms above, and, at peak runoff in June, is thunderous and spectacular as protrusions in the granite throw wheeling sprays of water far out into the air. Don’t be in a hurry because these falls are best viewed from below, and on a hot day, you’ll appreciate their cooling spray as you begin to climb 600 feet up steep, exposed switchbacks north of the falls.

The trail returns to the river just above the brink of the falls, but the ascent pauses just briefly, soon climbing up an open, juniper-dotted slope, then passing close to the river at Le Conte Falls. These are my favorite of the cascades for a long break, for you can share the granite slabs with the tumbling water, giving you a good vantage point of some smaller waterwheels.

Leaving behind the last incense cedars and sugar pines, the trail becomes increasingly steep and sunny until you pass close beneath the massive south buttress of Wildcat Point. The grade eases just before you reach California Falls, and a relatively short climb then brings you to the top of these, the last of the three major falls below Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp. Glen Aulin itself, the valley through which you soon pass, was extensively burned in 1987 and much of the ground is covered with crisscrossing trunks, with the only campsites tiny nooks near the valley’s northern walls about halfway along the glen. At the western end of the glen, you cross the outlet creek from Mattie Lake, which at times disperses to cover 300 feet of trail. Indeed, long stretches of trail through Glen Aulin are wet during June—if you’ve come when the waterfalls are at their peak, it is wise to accept wet shoes and just wade through here.

CYCLES OF NATURE

This walk takes you through landscape bearing a mosaic of fire scars, the most recent around White Wolf, from 2010, 2014, and 2020. Following fire, species that can resprout, including aspens in Glen Aulin and black oaks at lower elevations, are the first to “bounce back,” providing a splash of green within a year. If a fire is sufficiently hot, the conifers die and take decades to reestablish. Glen Aulin was burned more than 30 years ago, but the lodgepole pines have only recently started producing cones, and later germinants, like firs, will take many more years to become mature trees.

After more than a mile of level ground, you leave Glen Aulin and briefly climb slabs to a junction with the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT). Turn right (south) on the PCT and almost immediately meet a spur trail left (east) that crosses Conness Creek on a bridge to Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp. There is a backpackers’ campground with pit toilets, piped water, and bear boxes at the back of the camp. This is the last legal camping before Tuolumne Meadows, so you must either stay here (7,930'; 37.91051°N, 119.41699°W) or complete the entire distance described under Day 4.

DAY 4 (Glen Aulin High Sierra Camp to Tuolumne Meadows, 5.4 miles): Follow Trip 31, Day 8 to the Glen Aulin Trailhead.

If you need to take a YARTS shuttle bus back to White Wolf, from Lembert Dome, walk west along the shoulder of CA 120 to the Tuolumne Meadows store.