Section

1:

THE EARLY PRINTS

THE AESTHETIC heart of any ukiyo-e collection must be found among prints like those presented in this section, for here the basic spirit of ukiyo-e asserts itself, and without an appreciation of these early prints one can never savor the essence of this enchanting art form. Fortunately, a fair number of these are in circulation today, and some of the finest are not prohibitively expensive, being within the reach of any collector.

Technically, ukiyo-e developed from book illustrations printed by means of carved wood blocks, and it was from such a page that Print 257 was taken. As the artists' skill grew, it was easy to drop the text from the book and offer albums composed solely of black-and-white prints. These were the sumizuri-e which were discussed earlier, and four of the most pleasing are shown as Prints 17-20. Some of the finest ukiyo-e appeared originally in such albums, and many sheets are still available at reasonable prices. Print 18 was among the first ukiyo-e I purchased, and it remains one of my favorites, a storybook thing whose joyous, saucy line catches the spirit of this art. If I were interested in the essence of ukiyo-e and could afford only one print, I would not select either a Harunobu or a Sharaku, for I might study such a color print without ever discovering what it was that made ukiyo-e great; unquestionably I would choose a sumizuri-e, say Moronobu's masterwork, Print 11, for then I would see constantly before me the essence of the art: its singing line.

From album sheets bound together to summarize a popular story or erotic incident it was an easy jump to single sheets which stood forth as their own justification, and it is these towering sheets that are the glory of ukiyo-e. Print 15 is a classic example and one of the high points of this collection. The two Kiyomasus, Prints 21 and 23, show what vigor could be obtained. Such sheets are excessively rare; fortunately, they are not essential to a basic understanding of ukiyo-e, for one can also learn the lessons they teach through the lesser album sheets. But as artistic units, the swirling Kaigetsudo women, standing aloof and solemn against their white and formless background, are wonderfully pleasing. Furthermore, they epitomize the early period, during which the ukiyo-e artists did their strongest work.

The next step in the development of ukiyo-e was inevitable. Print 16 shows what gratifying results were achieved when one of the massive sumizuri-e was turned over to a worker who daubed it with primitive colors; legend says that the original artist rarely bothered with this brushwork, leaving it to someone else, preferably elderly women. The red lead, called tan, was especially effective, and prints which featured it were popularly called tan-e. Prints 16, 22, and 25 feature tan.

The next development was a multiple one, consisting of three distinct parts, and which came first is difficult to say, but Print 28 is an example of what occurred. First, the color palette was broadened; tan was dropped and the artist was free to choose from more than a dozen different colors. In this case Kiyomasu used red, pink, yellow, khaki, and smoky gray. Second, gold dust was sprinkled over selected areas, here the foremost boat, in order to heighten visual appeal, Third, urushi, a lacquer-like substance often made of black ink and cheap glue, was daubed over areas that were required to stand out, in this case the woman's coat, lending them a scintillating brilliance. Adding these three innovations together, one gets the famous urushi-e, "lacquer print." Sometimes, as in Print 24, the urushi was not mixed with black but appeared as a thin, glistening, translucent fixative. The collector who loves urushi-e is fortunate, for many of these prints are in circulation at modest prices. I find them delightful, small in size, sometimes gaudy in execution, but always evocative of the beginning days of the art. In many ways they resemble primitive Italian paintings depicting the lives of lesser saints: they are awkward, flamboyant, and tenderly reverent. Urushi-e depict not saints but actors, as in the case of Prints 24, 26, and 27, and I commend these affectionate little prints most warmly, for one can often derive from them a personal pleasure that larger, more polished prints do not generate. As we saw in the case of tan-e, the three components-the colors, the gold dust, and the urushi-were applied by hand and pretty surely not by the artist himself.

10. TOYONOBU: Girl after Bath. Page 262

The next development was a crucial one, and from it grew the later perfections of ukiyo-e. Print 73 was not colored by hand. It was printed exclusively from blocks, the black outline having been obtained from the key block, the rose-red from a second and completely separate block, and the apple-green from a third. This innovation of printing colors from blocks rather than applying them by hand produced startling results. At first, however, its use was restricted to two colors only, rose-red and apple-green, and since the former is known as beni, the two-color prints are called benizuri-e, "red-printed pictures."

Why these particular colors were chosen no one knows, nor are we sure what artist first used them, although there is a suspicion that Masanobu in some work like Print 51 may have done so. It is an extraordinary fact, possibly unmatched in art history, that for more than a decade a group of vivid, experimental, and strong-minded artists were willing to confine their palette largely to these two apparently haphazardly selected colors. On the other hand, some of the choicest ukiyo-e resulted from this discipline, for when one's eye becomes accustomed to rose-red and apple-green one derives from their skillful juxtaposition an entire range of color values. In this book Prints 73 and 81, among others, illustrate what was accomplished in this form, but since the beni used fades rapidly when exposed to light, their original impact is today somewhat diminished.

I should now like to make one simple recommendation to anyone wishing to start an ukiyo-e collection: acquire an album sheet, an urushi-e, and a benizuri-e. This can be done at no great expense, although it may take several years to find appropriate bargains. With good examples of these three beginning types, the collector can add what he will, or avoid what he does not like, yet always be sure of having a selection founded upon the artistic principles that made ukiyo-e originally popular in the streets of Edo and later treasured in the art galleries of the world.

More tardily than one might have expected, ukiyo-e artists mastered the technique of keeping three different colors in register, as demonstrated in the print on this page where blue joins red and green. In Print 85 gray was the third color, and in others yellow was added with great effectiveness. Obviously, at this point the ukiyo-e artists were aesthetically ready to make prints utilizing the full color spectrum; but they had to wait a while for the perfection of some device that would insure perfect registry of their blocks through eight or ten different printings, for this simple trick of printing with many colors was not yet forthcoming.

For the time being the artists experimented with a technique that proved to be somewhat less than successful. In Print 98 the artist has used three basic colors; red, green, and blue. But for the actor's outer robe he has also experimented with this new technical development: he has printed blue over red in an attempt to produce purple. But the result is rather muddy, for the two components have remained separated and have not blended. Similarly, in Print 85 red has been overprinted by gray in a most unsatisfactory attempt to achieve purple. The collection contains several dozen prints showing the basic failure of this particular experiment. Blue and yellow should yield green, but only when mixed; when one is merely superimposed upon the other the colors remain blue and yellow and the result is muddy. But these prints do prove that the buying public was hungry for more color and that the artists were eager to produce it; in this technical impasse the era of the early prints ended.

These prints are also interesting for other technical reasons. Print 43 has been reproduced as large as possible to show how the early ukiyo-e artists were fond of experimenting with European perspective, which they studied in pictures introduced by the Dutch at Nagasaki. Such perspective prints are called uki-e, loosely "bird's-eye pictures," and it is noteworthy that Japanese artists rejected what we think of as accurate perspective because they preferred the tilting Asiatic convention, as shown in Prints 9 and 52, which produced pictures that were much more pleasing to them.

Print 50 shows how Japanese artists used wood blocks to achieve the same effect the Chinese had obtained from stone rubbings, and the Japanese name for such prints, ishizuri-e, "stone-printed pictures," indicates this derivation. Print 36, of which more later, shows how pleasing such prints can be.

When the smaller prints known as hoso-e, "narrow pictures," became popular, publishers found it convenient and no doubt profitable to carve onto one large block three related pictures, with each one separately tided and signed. To rich patrons they sold the entire unsevered triptych, as shown in Prints 86-91. A few such complete triptychs have come down to us, and they are rare and treasured. More often, the canny publisher cut his big sheets into three separate items for quicker sale to his poorer customers; but in later years collectors were occasionally able to reassemble these cut triptychs. Thus the three perfectly matched single sheets, Prints 93-95, must have come from the same original big sheet; but more often collectors have stumbled upon three different prints from three different original sources, as seems to have been the case with Prints 68-70.

At the same time, publishers occasionally provided their artists with choice large pieces of wood upon which single designs rather than triptychs were cut, and these again are treasured items. Prints 81 and 92 were carved upon such oversized blocks, the latter being instructive in that it shows how poorly the artists usually designed such large areas, being more at home in smaller compositions.

On the other hand, these artists exhibited the most extraordinary skill in designing tall, narrow prints. They varied from fairly wide prints like 33, through standard sizes like Prints 76 and 83, and on to the culmination of this branch of the art, the extremely narrow print shown on the facing page. The wider prints were known as kakemono-e, "hanging-thing pictures," and the narrowest as hashira-e, "pillar pictures."

In leaving these early prints one must not forget that when ukiyo-e reached Europe to dazzle and instruct the impressionists and to startle the general art world, it was not these early prints that did the work; the international fame of ukiyo-e has always rested on the later color prints. Nevertheless, many collectors find their greatest joy in these earlier prints, a choice that is neither affectation nor antiquarianism. These early prints are bold, vigorous in design, excellently drawn. They are authentic Japanese art from one of the great periods of Japanese history and as such are treasured.

The Beginnings:

FIVE OF the handsome sumizuri-e which mark the beginnings of ukiyo-e are shown in this first group. Print 12, one of the most interesting, had small areas of hand-applied color, and is thus disqualified as a pure sumizuri-e, but since the color was probably added later and has been deleted from the present reproduction, it is not altogether inappropriate to include the print here.

The basic characteristic of these early prints, a flowing line which is used in varied ways to express emotion on the one hand and to enclose interesting spatial areas on the other, is nowhere better exemplified than in Print 11, where the bold, black line fairly sings. The movement of the drapery of the mosquito net from lower left to upper right, repeated in the two female figures, is Moronobu at his best, and although the print is florid in design and therefore not typically Japanese, wherever the line goes it is of itself interesting.

In the original print the blacks are of an intensity that is difficult to reproduce by means of printer's ink. They create such powerful contrasts that the addition of what we commonly call color-red or green, for example-would merely detract from the dynamic quality of the print. Its color, as in the case of all really fine sumizuri-e, already exists in its blacks, and no other is needed.

Print 12 is one of the most joyous works in this book. It shows a typical highway scene of a two-sworded samurai hiking to the right, having just passed a group of five chattering ladies who, with their two servants, are walking to the left. There is the customary Moronobu interplay between the groups, while in the background appear the fragments of landscape, artistically positioned and artfully drawn, that set the stage. There are eight or ten such Moronobu sheets that combine rural travel and impressionistic landscape, and they have always seemed to me almost the essence of the Genroku period. They are intensely Japanese: simple, poetic, handsomely achieved, and evocative of nature. I enjoy them enormously and wish I had others besides this one.

The artist who did Print 13 is a fascinating person; for nearly three centuries he had no artistic existence, his prints having been assigned totally to Moronobu. Then the Japanese expert on erotic prints, Shibui Kiyoshi, noticed that on many prints hitherto ascribed to Moronobu appeared the character Mura or the inconspicuous word Jihei, and working upon this clue he began to resurrect the artistic personality of Sugimura Jihei and to take from Moronobu many prints that were once ascribed to him. This collection contains two additional Sugimura prints of high quality, the black line being especially good, but they are too erotic in content to be reproduced. I regret this, for they demonstrate what artistic effects can be achieved by this singing line.

Single-page prints by Sukenobu are excessively rare. I know of less than a dozen subjects and it is only by accident that one happens to appear in this collection. I stumbled upon it one day in a folio in London, and although a more appropriate subject for this most successful early portrayer of young women would have been one of his traditional beauties, the print shown here is a fine Sukenobu and one of the rarities of the collection.

As for Print 15,1 have already discussed the problem of finding a Kaigetsudo, and here I should like merely to stress again that the powerful blacks of this early period provide their own color. A fair portion of the great Kaigetsudo prints are handcolored, but like most collectors, I much prefer those that are not, and this print, somewhat more florid in design than I should have liked, demonstrates why color is not required. If one seeks a single print by which to summarize the impact of ukiyo-e, he customarily selects one of these large black-and-white figures of standing women. It is an appropriate choice and one with which I would not wish to argue.

11. MORONOBU: Lovers with Attendant. Page 254

12. MORONOBU: Groups of Travelers. Page 254

13. SUGIMUKA: Lovers by a Screen. Page 254

14. SUKENOBU: Hairdressing. Page 255

15. KAIGETSUDO DOHAN: Courtesan. Page 255

Kiyonobu Kiyomasu:

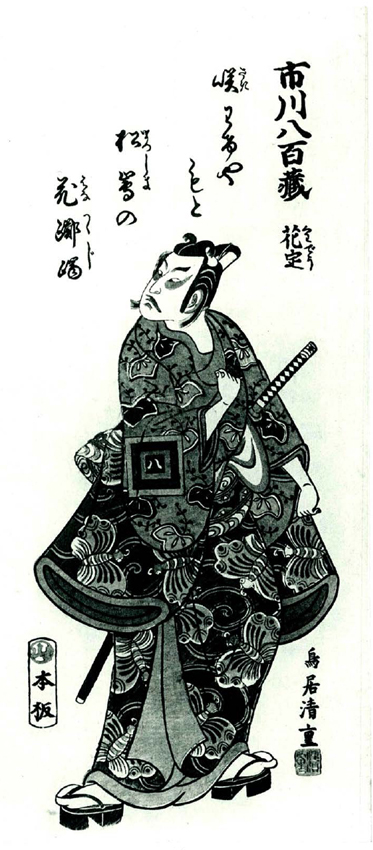

ALL BOOKS on ukiyo-e face the perplexing problem of how to explain the relationships between the two or three different men who called themselves Kiyonobu and the two different men who used the name Kiyomasu. I have argued the problem elsewhere, and here I should like merely to point out some of the major types of prints produced by these excellent artists of the Torii school. They did sumizuri-e albums, some of whose pages are shown in Prints 2 and 17-20. They did marvelous big prints, both as sumizuri-e, Prints 21 and 23, and as tan-e, shown opposite. They did hundreds of hoso-e, some in tan-e form, like Prints 22 and 25, but most in urushi-e, like Prints 27 and 28. And at the end of their careers they issued many benizuri-e, of which this collection has numerous examples; none are reproduced because it was thought that readers would prefer to see the rarer urushi-e.

Were an informed collector given his choice of all the prints contained in this book, he would probably select, in this order: first, the print opposite; second, the Kaigetsudo woman, Print 15; third, the Kiyonaga night diptych, Prints 145-46; and fourth, the Tare Choki snow scene, Print 174. Certainly, the big tan-e facing this page is one of the finest prints of its kind; when the Japanese publishers of the Ukiyo-e taisei, which reproduces over five thousand prints for quick reference, sought a distinctive cover for their series, one which would remind the public of the power of ukiyo-e, they chose this Kiyomasu, and as a result it has become the most widely known of all tan-e. It is also a glowing indication of why collectors have always prized Torii art. The artistic merits of this print are great: the position of the actor, his balance, the counterpoising of the umbrella, and the harsh modeling of the drapery combine to produce a most striking design.

If Print 16 is a gem among the larger sized prints, Print 24 is a no less noble example of what can be achieved within the narrower measure of the hoso-e. This print seems to me extraordinarily winning in its design-perfect even in the placement of the title and signature-color and general effect.

Prints 29 and 31 are of importance in the study of ukiyo-e because they effectively illustrate the two basic characteristics of Torii art. The first is known as hyotan-ashi, "gourd legs," a convention of drawing legs in the shape of gourds to produce an illusion of strength, which before long was also applied to arms. And the second was mimizu-gaki, "worm drawing," whereby the design was achieved through using lines that looked like wiggling worms, thereby lending a sense of frenzy and dramatic chaos to the print. These two conventions help explain why Torii prints caught so effectively the spirit of the Kabuki theater, which in many of its plays specializes in frenzy and rude power.

Prints 28, 30, and 32 are by Kiyomasu II, and their presence in this book requires something of an apology. Earlier I wrote of this strange artist: "Kiyomasu II is responsible for some of the most boring art in ukiyo-e, disasters consisting of one actor standing and one seated." I still think the bulk of his work boring, but Print 28 shows what he could accomplish when he avoided stock design; so far as I know this is his masterpiece. Print 30 is one of the best of his standard subjects. And as for Print 32, I have actually grown fond of it, for it epitomizes the wiggling-worm school of art and I believe the casual reader will also discover a certain frenzied joy in its lively design. One of the pleasures of art is constant re-evaluation of what constitutes merit, and ukiyo-e provides fascinating subject matter for such review. The possessor of a print is forced to decide what he thinks about it, and in arriving at conclusions his artistic sensibilities are sharpened, which is a very good thing.

16. KIYOMASU I: Nakamura Senya in the Role of Tokonatsu. Page 256

17. KIYOMASU I: Goro, Shosho, and Asahina. Page 256

18. KIYOMASU I: Saint Narukami and Princess Taenia. Page 256

19. KIYOMASU I: Agemaki and Sukeroku. Page 256

20. KIYOMASU I: Fuwa and Okuni. Page 256

21. KIYOMASU I: Warriors in Combat. Page 256

22. KIYOMASU I: Takie, Shingoro, and Danjuro. Page 256

23. KIYOMASU I: Heihuro and Takesaburo. Page 256

24. KIYOMASU I: Fujimura Handayu. Page 255

25. KIYOMASU I: Courtesan. Page 256

26. KIYOMASU II: Fujimura Handayu. Page 257

27. KIYOMASU II: Segawa Kikunojo. Page 257

28. KIYOMASU II: The Maiden Tamamushi., Page 257

29. KIYOMASU II: Kantaro and Takenojo. Page 255

30. KIYOMASU II: Danjuro and Hiroji. Page 257

31. KIYOMASU II: Ichikawa Kuzo. Page 255

32. KIYOMASU II: Segaiva Kikujiro. Page 257

Masanobu:

MY FAVORITE ukiyo-e artist is Masanobu, which accounts for the fact that I have here allotted more prints to him than to any other. He is important because he arrived on the scene when ukiyo-e was in danger of petrifaction. Men like Moronobu, Kiyonobu, the Kaigetsudo artists, and Sukenobu had given the art a vigorous initial impulse, but as their fires died down, prints fell into ritualistic patterns of color, design, and content. It was mainly Masanobu who blasted the art loose from such conventionalism and launched it upon vigorous new paths.

The six hoso-e shown together, Prints 46-51, fairly well summarize his art experience. Starting with Prints 48 and 49, he issues urushi-e that are as muscle-bound as anything done by the Torii school. The design is formal, the drawing harsh, and the coloring heavy. But in Print 46 he gives us a handsomely designed little print in black and gray; while in Print 47 he offers one of the loveliest urushi-e that was ever issued. I am sorry that it could not be shown in color, for it is a gem. In Print 50 he experiments with ishizuri-e, and late in life he comes up with many perfect benizuri-e, as for example, Print 51.

He is supposed to have initiated the following new ideas that revitalized ukiyo-e: urushi-e; gold dust; mica grounds; European perspective; the triptych form; the tall upright print, narrower than the size used by the Kaigetsudo and Torii masters; the narrow pillar print; the ishizuri-e; the landscape print; the embossing which Harunobu later used with such success; the selection of rose-red and apple-green as basic colors for benizuri-e; and the printing of all colors from blocks. Most of these supposed Masanobu inventions are illustrated in the nineteen prints shown here.

It is appropriate that the emotional highpoint of this collection is found in the sadly worn pair of Masanobu prints appearing as 39-40. They show the nonpareil Sukeroku and, possibly, his love Agemaki. I do not feel capable of describing what Sukeroku means to a Japanese theater audience when he swaggers down the hanamichi, defying the authorities by wearing about his head a knotted scarf of purple, a color forbidden to commoners. I have heard Japanese men whistle and shout when he appeared; women have wept. These prints are in such wasted condition that normally I would not have kept them; but they are more than prints: they are the finest extant portrayals of the Robin Hood of Japan and his love and they symbolize the spirit of Masanobu. Other recollections of the Sukeroku drama are found in Prints 81, 123, and 133-35.

The famous design which appears here as Print 36 presents a difficult problem. Most European and American critics have always accepted it as a brilliant example of Masanobu's skill, and in Hillier's book on ukiyo-e it is accorded a place of honor. Japanese critics and Dr. Lane, however, condemn it as a much later issue, an opinion in which I concur. It is reproduced to show fellow collectors that sooner or later every collector makes major mistakes.

Print 38 is one of the most distinguished in this book insofar as history is concerned. The print occurs in four distinct versions: as a much wider kakemono-e showing the full body of the actor; in the same form but with a marked split running from the left heel of the actor up to his left shoulder; the form shown here, which was made from the original block after it had been neatly sawed down the split; and in a completely recut version. The first and last versions can be seen in the Chicago catalogue, Masanobu 95 and 96. The second can be seen at Boston. The present copy, which has been widely reproduced, is the best extant of the third version and is well known for that reason. Finally, to show what a canny publisher and artist Masanobu was, he redid the whole print with all new blocks and made it into a benizuri-e, as shown in the Ukiyo-e taisei. III, 106.

33. MASANOBU: Young Samurai on Horseback. Page 257

34. MASANOBU: Cutting up the Flute for Firewood. Page 257

35. MASANOBU: Lovers Playing Checkers. Page 258

36. "MASANOBU" (19th-century imitation): Courtesan Walking. Page 258

37. MASANOBU: Girl with Mirror. Page 258

38. MASANOBU: Onoe Kikugoro. Page 258

39. MASANOBU: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 258

40. MASANOBU: Courtesan Walking. Page 258

41. MASANOBU: Sanokawa Ichimatsu with Puppet. Page 258

42. MASANOBU: Courtesan with Love Letter. Page 258

43. MASANOBU: Evening Coll by Ryogoku Bridge, Page 258

44. MASANOBU: Sanokawa Ichimatsu. Page 258

45. MASANOBU: Shidoken the Storyteller. Page 259

46. MASANOBU: Kuo chü Thanks Heaven. Page 259

47. MASANOBU: Actor in Snow. Page 259

48. MASANOBU: Sojuro and Kantaro. Page 259

49. MASANOBU: Ichikawa Monnosuke. Page 259

50. MASANOBU: Hsü and Ch'ao Resist Temptation. Page 259

51. MASANOBU: Sanokawa Ichimatsu. Page 259

Minor Masters:

IN EVERY period of ukiyo-e, side by side with the acknowledged masters there flourished a small, lively group of capable workmen who turned out minor prints of persuasive charm. In the early period, among the more commendable were those who appear in this next group, and a collector who could gather together one or two good examples of the work of these men could well forgo the most expensive prints, for here he will find most of the beauties of ukiyo-e capably exemplified.

The print reproduced in color on the opposite page is an appropriate opening to such a section, for its author is not known. Up to now it has always been catalogued as a Masanobu, and it compares favorably with his best urushi-e; but Japanese critics doubt that it was done by that master. Some think it might be by Toshinobu; others question that attribution. I feel that it is close to Masanobu; Dr. Lane suggests that it may be the work of another, unknown master, working after the manner of Toshinobu. At any rate, it is a perfect little gem of a print, colorful, musical, flecked with gold and sparkling with urushi. The reader is invited to make his own attribution.

As a result of some happy accident, the collection is unusually strong in urushie by Toshinobu, and the four designs chosen here to fill two pages, Prints 57-60, were selected purposely to show as many characteristics of this fine print-maker as possible. He loves strong color, clashing designs, and movement. For many years he was supposed to have been the son of Masanobu, but firm dates recently established for some of his prints require Masanobu to have been ten when he sired him, after which Toshinobu began designing polished work at the age of nine months, both of which events seem unlikely. Whoever he was, he is most congenial and his prints are minor lyrics.

Shigenaga, represented here by Prints 61-64, is a focal figure in ukiyo-e because, with his harsh angular style, he produced many prints that strike us with their power; furthermore, he taught a host of successors on whom much of the subsequent glory of ukiyo-e rests: Toyonobu, Harunobu, Koryusai, Shigemasa, and Toyoharu, the latter of whom taught Toyohiro, who taught Hiroshige. The two prints of Shoki the Demon Queller present an interesting problem in that in the Western world such prints have always commanded high prices; in Japan they sell for little, for they were originally painted as good-luck charms to ward off evil and are thus not counted true art objects.

Academically, the highlight of this section is the pair of Mangetsudo triptychs, Prints 65-70. They were once a part of the Hayashi collection, became separated, and are here published together for the first time. They are important because they provide a summary of this little-known man's work. In their Japanese Colour Prints, Binyon and Sexton use as the first color plate a handsome benizuri-e by Mangetsudo; otherwise we do not know much of his accomplishment. Prints 65-67 show him to have been weak in design, fond of clutter, and unable to achieve a unified effect. Prints 68-70 show just the opposite, for the gothic-style design is unusually effective, and the black line by which it was achieved is both strong and rhythmic. But this very excellence raises serious suspicions, for this print exists in the Stoclet collection in Brussels, with marked variations in design, fully signed by Masanobu. It can be seen in the Happer catalogue. Other versions have been found signed Hogetsudo and Kogetsudo, so that Dr. Lane raises the interesting query: "Is it not possible that Mangetsudo might be only a name used by a pirate publisher when reissuing Masanobu's work, and not an artist at all?"

52. STYLE OF TOSHINOBU: Girl Playing Samisen. Page 260

53. WAGEN: Yamashita Kinsaku. Page 259

54. KIYOTOMO: Yamamoto Koheiji with Puppet. Page 259

55. TERUSHIGE: Mangiku and Danjuro. Page 260

56. KIYOTADA: Osome and Hisamatsu. Page 260

57. TOSHINOBU: Ichikawa Gennosuhe. Page 260

58. TOSHINOBU: Sanjo Kantaro. Page 260

59. TOSHINOBU: Monnosuke and Wakano. Page 260

60. TOSHINOBU: Sanjo Kantaro. Page 260

61. SHIGENAGA: Descending Geese at Katata. Page 260

62. SHIGENAGA: Shoki the Demon-queller. Page 261

63. SHIGENAGA: Shoki the Demon-queUer. Page 261

64. SHIGENAGA: Sanokawa Ichimatsu. Page 261

65-67. MANGETSUDO: Yoshiwara Kotnachi. Page 261

68-70. MANGETSUDO: Lovers under Umbrellas. Page 261

71. SHIGENOBU: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 261

72. SHIGENOBU: Girl Selling Flowers. Page 261

The End of an Epoch:

ONE OF the more interesting problems of ukiyo-e concerns the authorship of the two prints on the facing page. They are clearly signed as having been done by Shigenobu, and a fairly large number of other prints similarly signed exhibit identical characteristics, so that there can be little doubt that we are dealing with one man who issued a consistent body of work. Some of his awkward and angular compositions are pleasing and demonstrate that Shigenobu, whoever he was, had an interesting artistic personality. He worked only a brief time, then vanished, and it has always irritated critics that one so important should have no secure place in the history of ukiyo-e.

At the same time another mystery perplexed the critics: Why did Toyonobu, the artist whose highly skilled work follows, leave no early prints showing his apprenticeship? By a process of logic a clever scholar decided that both of these irritating gaps could be filled by one simple theory: Shigenobu was the name used by Toyonobu when the latter was beginning; and elsewhere I confidently reported this rather clever deduction, as did most catalogues and auction lists.

Now we are not so sure. There seem to be pretty substantial stylistic differences between the work of the two men, enough at least to counsel hesitancy; the reader is invited to compare the Shigenobus with the Toyonobus. At the same time he should make his own estimate as to which of two very popular prints borrowed from the other: Prints 60 and 72.

Print 73 is one of historic importance, and when Frank Lloyd Wright owned it he described it in the following terms, not conspicuous for their temperance: "The noblest design of the primitive period in flawless state and one of the noblest Japanese prints of any kind in existence. A triumph over the Hmitations of the two-color print. . . . Certainly one of the most important things that has appeared." This print was among the first to show American collectors how brilliant a benizuri-e could be when its original colors were preserved, and it is reproduced here in color to reiterate that fact.

Print 81 is perhaps even more treasured, faded though it is, for it is a handsome design, and no other copy is known to the author, although others probably exist without having been published. Print 82 is being published with a special purpose in mind. In the early iooo's the American market was flooded with adroit counterfeits of benizuri-hoso-e, and they were so well done that many of them got into museum collections. The present collection appears to contain several. For some years Print 82, which also reached America via Frank Lloyd Wright, was suspected of belonging to this notorious group of forgeries, and some critics challenged it. About thirty years ago the print was sent to Japan for authentication, and critics there not only accepted it but proudly reproduced it in Ukiyo-e taika shusei as an example of Toyonobu at his best. Even so, I had doubts about its validity and took the print with me to Japan in 1957, where a new generation of scholars studied it and found it identical with the great Toyonobus now housed in the Ueno Museum.

The last two color plates, Prints 93-95 and 98, show the excellent work being done on the eve of full-color printing. The first is a standard-type benizuri-e to which a striking blue has been added, yielding a curious color harmony indeed, but one not inappropriate to the subject matter. Print 98 merits careful study, for as noted earlier, it utilizes three basic colors and achieves a fourth by overprinting. Technically, it marks the end of the early-print epoch.

73. TOYONOBU: Ichimatsu and Kikugoro. Page 262

74. TOYONOBU: Ichimatsu and Kikunojo. Page 262

75. TOYONOBU: Maiden. Page 262

76. TOYONOBU: Girl Holding Umbrella. Page 262

77. TOYONOBU: Girl with Flowers. Page 262

78. TOYONOBU: Girl with Umbrella. Page 262

79. TOYONOBU: Girl with Lantern and Fan. Page 262

80. TOYONOBU: Courtesan and Maidservant. Page 262

81. TOYONOBU: Ichimatsu and Kikugoro with Puppets. Page 262

82. TOYONOBU: Young Man with Flower-cart. Page 262

83. KIYOSHIGE: Sanokawa Ichimatsu. Page 262

84. KIYOMISU: Bando Hihosahuro II. Pace 263

85. KIYOSHIGE: Ichikawa Yaozo. Page 263

86-88. KIYOHIRO: Couples under Umbrellas. Page 263

89-91. KIYOHIRO: Young People by the Waterside. Page 263

92. KIYOMITSU: Maiden Dreaming. Page 263

93-95. KIYOMITSU: Dancers. Page 263

96. KIYOHIRO: Hikosaburo and Kichiji. Page 263

97. KIYOMHSU: Ichikawa Ebizo. Page 263

98. FUJINOBU: Sanokawa Ichimatsu. Page 263