Chapter 8

Managing Inventory

In This Chapter

Understanding the importance of balancing inventory with customer demand

Understanding the importance of balancing inventory with customer demand

Using different systems to manage inventory

Using different systems to manage inventory

Evaluating your inventory management system

Evaluating your inventory management system

Using commonality and postponement strategies to reduce inventory

Using commonality and postponement strategies to reduce inventory

Looking at inventory across the entire supply chain

Looking at inventory across the entire supply chain

Inventory refers to all the forms of material eventually intended for sale that a business maintains, including raw materials, work in process, and finished products. In the past, maintaining large stocks of inventory was common practice in manufacturing because primary metrics for evaluating performance centered on utilization, or how busy the company’s resources stayed, and order fulfillment (or back-order reduction), which emphasized the ability to fill customer orders immediately. These metrics led managers to produce more products than were needed, and these parts ended up in inventory. (See Chapter 3 for info on what happens when a process overproduces.)

Now, many business leaders no longer view inventory as an asset but as a liability that ties up a firm’s working capital. Therefore, over the past several years, companies have made a tremendous effort using techniques such as just in time (JIT) to reduce the levels of inventory that they maintain (see Chapter 11 for more on lean manufacturing). But having too little inventory can be just as costly as having too much. Some inventory is necessary to maintain operations and ensure that products are available when customers demand them.

This chapter presents the basics of cost-effective inventory management. We point out why inventory is needed, explain the true costs associated with inventory, and describe three common inventory policies. But don’t worry — it’s inventory, not rocket science! Before all is said and done, we give you some specific methods for reducing inventory without sacrificing customer satisfaction. The chapter concludes with a discussion of inventory management across the supply chain.

Dealing with the Business of Inventory

Inventory has become the four-letter word of operations management. Balancing inventory to satisfy customer demand — that is, actual demand in the market for products and services — without exposing the company to unnecessary cost and risk is crucial. But this aspect of operations can be one of the toughest.

When the number of customers walking through your door ready to purchase your product or when the number of people adding your product to their online shopping cart is significantly different from what you expect, your business is exposed to demand risk. If customer demand exceeds expectations, then you don’t have enough product or resources to fill all customer orders. If demand is lower than expectations, then you’re left sitting with excess inventory.

The problem is that customer demand is variable and forecasts of demand are always inaccurate; in many cases, they’re way off (see Chapter 6). You can never really predict what actual customer demand will be. To manage this uncertainty, companies use inventory and capacity to hedge their bets.

By capacity, we mean the amount of product you can produce during a specific time period — widgets per hour, for example. You need capacity to make inventory.

Chapter 7 covers how to manage capacity; for now, all you need to know is that, in order to meet unexpected surges in demand, companies need to have one of the following:

Sufficient inventory available

Sufficient inventory available

Sufficient additional capacity (often called surge capacity) to make additional products in a time period acceptable to customers

Sufficient additional capacity (often called surge capacity) to make additional products in a time period acceptable to customers

If fewer than expected customers want your goods, you’ll be left with excess inventory in the first case or excess capacity in the second case. Keep in mind that extra capacity requires extra investment in facilities and capital equipment.

In this section, we point out why you need to have adequate inventory. We also lay out the real costs associated with this often-scary part of business.

Recognizing inventory’s purposes

There’s just no way around it for most businesses: If you’re going to sell products, you need to have stuff available for customers to purchase.

Here are some of the important functions of inventory in successful operations:

Meeting customer demand: Maintaining finished goods inventory allows a company to immediately fill customer demand for product. Failing to maintain an adequate supply of FGI can lead to disappointed potential customers and lost revenue.

Meeting customer demand: Maintaining finished goods inventory allows a company to immediately fill customer demand for product. Failing to maintain an adequate supply of FGI can lead to disappointed potential customers and lost revenue.

Protecting against supply shortages and delivery delays: A supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and accessibility to raw materials is sometimes disrupted. That’s why some companies stockpile certain raw materials to protect themselves from disruptions in the supply chain and avoid idling their plants and other facilities.

Protecting against supply shortages and delivery delays: A supply chain is only as strong as its weakest link, and accessibility to raw materials is sometimes disrupted. That’s why some companies stockpile certain raw materials to protect themselves from disruptions in the supply chain and avoid idling their plants and other facilities.

Separating operations in a process: Inventory of subassemblies or partially processed raw material is often held in various stages throughout a process. Work in process inventory (or WIP) protects an organization when interruptions or breakdowns occur within the process. Maintaining WIP allows other operations to continue even when a failure exists in another part of the process.

Separating operations in a process: Inventory of subassemblies or partially processed raw material is often held in various stages throughout a process. Work in process inventory (or WIP) protects an organization when interruptions or breakdowns occur within the process. Maintaining WIP allows other operations to continue even when a failure exists in another part of the process.

Smoothing production requirements and reducing peak period capacity needs: Businesses that produce nonperishable products and experience seasonal customer demand often try to build up inventory during slow periods in anticipation of the high-demand period. This allows the company to maintain thruput levels during peak periods and still meet higher customer demand.

Smoothing production requirements and reducing peak period capacity needs: Businesses that produce nonperishable products and experience seasonal customer demand often try to build up inventory during slow periods in anticipation of the high-demand period. This allows the company to maintain thruput levels during peak periods and still meet higher customer demand.

Taking advantage of quantity discounts: Many suppliers offer discounts based on certain quantity breaks because large orders tend to reduce total processing and shipping costs while also allowing suppliers to take advantage of economies of scale in their own production processes.

Taking advantage of quantity discounts: Many suppliers offer discounts based on certain quantity breaks because large orders tend to reduce total processing and shipping costs while also allowing suppliers to take advantage of economies of scale in their own production processes.

Measuring the true cost of inventory

Maintaining inventory is expensive; it diverts resources from other areas of your business. But not having enough inventory can lead to lost sales and inadequate customer service. Therein lies the rub. Getting too far off the delicate balance of appropriate inventory for your business puts you in dangerous territory.

When deciding how much inventory to carry, an operations manager must balance the costs of having too much with the risk of coming up short. The different costs of inventory touch every area of business:

Ordering costs: The costs of ordering and receiving inventory vary for each business, but these costs include the labor associated with placing an order and the cost of receiving the order. Ordering costs are usually expressed as a fixed dollar amount per order, regardless of order size.

Ordering costs: The costs of ordering and receiving inventory vary for each business, but these costs include the labor associated with placing an order and the cost of receiving the order. Ordering costs are usually expressed as a fixed dollar amount per order, regardless of order size.

Holding or carrying costs: The cost of physically having inventory on-site includes expenses to maintain the infrastructure needed to warehouse the goods and insurance to protect it.

Holding or carrying costs: The cost of physically having inventory on-site includes expenses to maintain the infrastructure needed to warehouse the goods and insurance to protect it.

Additionally, the value of inventory can decline because of deterioration and obsolescence, which adds to the cost of storing inventory. This is particularly true of perishable goods such as food and medicine, but even nonperishable products can go out of style or become obsolete. And inventory can be damaged or “disappear” off the shelf when it’s being stored, which in operations lingo is called shrinkage.

Additionally, the value of inventory can decline because of deterioration and obsolescence, which adds to the cost of storing inventory. This is particularly true of perishable goods such as food and medicine, but even nonperishable products can go out of style or become obsolete. And inventory can be damaged or “disappear” off the shelf when it’s being stored, which in operations lingo is called shrinkage.

Lost sales: If a product isn’t available, then you can’t sell it. Unless a customer is willing to wait for delivery while you produce and/or prepare the product of interest, you lose the sale and the resulting revenue and profit by not having an adequate supply to meet demand.

Lost sales: If a product isn’t available, then you can’t sell it. Unless a customer is willing to wait for delivery while you produce and/or prepare the product of interest, you lose the sale and the resulting revenue and profit by not having an adequate supply to meet demand.

Goodwill costs: Alienating customers if your product is out of stock rolls back a considerable investment that your company has likely made in establishing goodwill in the market. Your loss in this situation includes other items that the customer doesn’t purchase when the product is unavailable as well as products he doesn’t purchase from you in the future because of perceptions about your company related to the initial shortage.

Goodwill costs: Alienating customers if your product is out of stock rolls back a considerable investment that your company has likely made in establishing goodwill in the market. Your loss in this situation includes other items that the customer doesn’t purchase when the product is unavailable as well as products he doesn’t purchase from you in the future because of perceptions about your company related to the initial shortage.

Though ordering and holding costs are usually easy to calculate, estimating the actual cost of lost sales and goodwill is more difficult. Many companies don’t have a way to track potential customers who wanted to buy a product that was unavailable and to determine whether the inventory snafu led to the loss of other sales. Nevertheless, accurately measuring these costs is important because they can significantly affect a company’s inventory policies and, ultimately, the bottom line.

The best way to measure goodwill costs varies by industry and by the nature of your product, but good market research and acute familiarity with your customer base are critical.

Managing Inventory

Inventory management is one of the most difficult tasks in operations because it’s hard to predict actual customer demand. You can approach inventory management in many different ways. The right one for any given situation depends on the specific business environment.

Establishing a cost-efficient inventory management system — a process that determines how much inventory you need and when — requires knowledge of three specific variables:

Customer demand forecast: Because point forecasts (a single estimate for expected demand) are always inaccurate, your forecasts should always include information on expected average demand and a measure of the potential variability in demand (see Chapter 6).

Customer demand forecast: Because point forecasts (a single estimate for expected demand) are always inaccurate, your forecasts should always include information on expected average demand and a measure of the potential variability in demand (see Chapter 6).

Inventory costs: Reliable estimates of inventory costs should contain expenses related to ordering and holding inventory and costs of lost sales and goodwill if insufficient inventory is available to meet demand.

Inventory costs: Reliable estimates of inventory costs should contain expenses related to ordering and holding inventory and costs of lost sales and goodwill if insufficient inventory is available to meet demand.

Lead time: Accurate estimates of expected delivery lead time for raw material and other manufacturing components (time between a placed order and delivery) and the variability of this time is critical to planning inventory levels. You also need to add in how long it will take you to process those materials into a finished product. Find out how to design your supply chain to meet delivery targets in Chapter 10.

Lead time: Accurate estimates of expected delivery lead time for raw material and other manufacturing components (time between a placed order and delivery) and the variability of this time is critical to planning inventory levels. You also need to add in how long it will take you to process those materials into a finished product. Find out how to design your supply chain to meet delivery targets in Chapter 10.

Many different inventory management systems are available, but they all share one goal: Get the right products to the right place at the right time. To figure out which system is the right one for you to achieve this goal in light of your business environment and infrastructure, you need to answer four basic inventory questions:

Can I reorder? In most cases, you can place orders to replenish stock that sells. But this isn’t always the case. In the fashion industry, for example, restocking isn’t usually an option. The best approach for managing inventory is fundamentally different for businesses that can and can’t restock inventory.

Can I reorder? In most cases, you can place orders to replenish stock that sells. But this isn’t always the case. In the fashion industry, for example, restocking isn’t usually an option. The best approach for managing inventory is fundamentally different for businesses that can and can’t restock inventory.

When can I review inventory levels? If you can reorder, choosing when to review inventory levels is crucial. Most often, inventory review can occur either continuously or periodically. If monitored continuously (hopefully this is automated), inventory can be ordered whenever a certain set point is reached. In many cases it’s impractical to keep a constant eye on inventory, so you can set a designated time period to review inventory levels and place orders; this is called periodic review.

When can I review inventory levels? If you can reorder, choosing when to review inventory levels is crucial. Most often, inventory review can occur either continuously or periodically. If monitored continuously (hopefully this is automated), inventory can be ordered whenever a certain set point is reached. In many cases it’s impractical to keep a constant eye on inventory, so you can set a designated time period to review inventory levels and place orders; this is called periodic review.

How much do I need to order? Regardless of the review system you use, you need to consider expected demand, costs, and delivery times when deciding how much inventory to order at any one time.

How much do I need to order? Regardless of the review system you use, you need to consider expected demand, costs, and delivery times when deciding how much inventory to order at any one time.

When is the best time to place an order? If you can reorder product, then you need to figure out when to place the reorder. This decision tends to go hand in hand with how you choose to monitor inventory levels.

When is the best time to place an order? If you can reorder product, then you need to figure out when to place the reorder. This decision tends to go hand in hand with how you choose to monitor inventory levels.

Modern inventory software makes monitoring inventory much easier than it was in the old days of counting boxes. Computer programs have all but eliminated the need to take a physical count of inventory in most cases. Counting usually takes place only at tax time to value the inventory or to verify the accuracy of the software count. This means you can now maintain a near-constant tally of inventory and even link with supplier systems, thereby automating the ordering process.

The periodic review system, despite requiring slightly higher inventory levels, offers many advantages over continuous review systems. It simplifies operations because you can set a specific time for a resource to place all necessary orders. It allows you to consolidate shipments if you purchase multiple products from the same supplier, and it simplifies life for the supplier because the supplier knows when to expect an order from you.

Effective inventory management hinges on choosing the best process for reviewing inventory levels, which depends on your particular business. Basically, inventory review can be continuous, periodic, or isolated as a single period. Most of today’s inventory review programs are based on one or more of these basic systems.

Continuous review

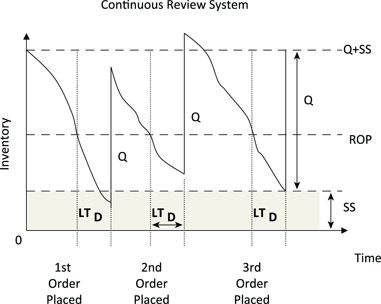

In continuous inventory review, you monitor inventory on an ongoing basis. You set a predetermined inventory level as the reorder point (ROP) and typically place a consistent order.

Figure 8-1 shows a continuous inventory review system, and on average, inventory falls by the average demand rate. If demand becomes higher or lower than normal, inventory levels change at a different rate.

Regardless of timing, when inventory falls to a specified point (represented by ROP) in the figure, an order is placed for a certain amount of goods (represented by Q in the figure).

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-1: Continuous inventory review system.

Depending on the nature of the products, a certain length of time (also known as lead time) passes between the time of order placement and delivery. Remember that demand can vary from the average during this time, and you may run out of inventory if demand is unusually high. To avoid inventory depletion, many companies maintain some inventory to cover above-average demand that may occur during the lead time; this inventory is known as safety stock (SS).

After the new order arrives, inventory is boosted beyond the reorder point, and continuous monitoring resumes.

Calculate the ROP using this formula:

Use this formula to determine how much SS you need to cover the risk of above-average demand during reorder lead time:

In this formula, z is the number of standard deviations above the mean in normally distributed demand. Its value depends on the service level (SL) — the probability that demand won’t exceed supply during the lead time — that the company wants to maintain. The SL increases as the risk of a stock out (running out of inventory) decreases.

Using Excel or some other table-based software, you can find z using this equation if you know the desired service level:

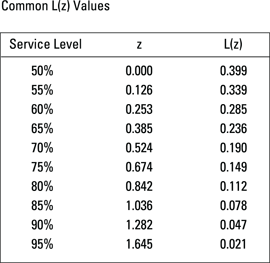

Figure 8-2 provides the z value for some common service levels.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-2: Common service level z values.

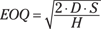

The economic order quantity (EOQ) — how much inventory you order when the ROP is hit — represents an order that minimizes total inventory costs.

In the following equation, D is the annual expected demand, S is the ordering cost, and H represents annual holding costs per unit. An order of EOQ is placed every time inventory falls to the ROP.

Periodic review

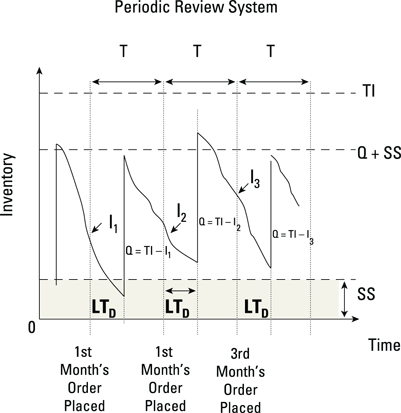

Continuously keeping your eye on inventory numbers can be inconvenient. After all, you have other things to do. Using periodic review, you can schedule time to assess the need to place an order for any additional inventory.

In a periodic system, you order inventory at certain time periods (T) to bring the total back to a designated target inventory (TI). Between the time you place and receive an order, higher-than-expected demand can cause a stock out. This situation is even more dire than in a continuous review approach because you must also account for the demand variability that occurs before the next review time.

The equation for the TI is similar to the ROP except TI must also account for the monitoring time interval. Here’s the formula to calculate TI:

Use this equation for calculating SS as part of a periodic inventory review system:

Figure 8-3 illustrates a periodic review system.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-3: Periodic inventory review system.

Often, you don’t have a choice about the monitoring time interval. For example, you may have to place orders every Friday. However, if you have the freedom to set a monitoring time interval, use the following equation to select a monitoring time interval that minimizes costs:

Regardless of how you determine T, every T time periods, you place an order for Q according to the following equation (where I is the current level of inventory):

Single period review

Sometimes, you need to make a one-time decision on how much to order, such as with seasonal items like snowblowers and swimsuits. At the end of the season, you typically liquidate any unsold items at significant price discounts to make room for new products for the next season.

In the single period inventory review model, the optimal quantity of inventory to order balances both the costs of understocking (Cu) and overstocking (Co) product. Cu is the sum of the lost profit per unit (usually price minus variable cost/unit) and the associated goodwill cost, which is the net present value of not having a unit of inventory on hand when a customer wants to purchase it. Co is the difference between the variable cost/unit of a product and its salvage value — often equivalent to the end-of-season clearance price.

You can calculate the desired service level for the product using this equation:

As defined, the service level is the probability that you won’t stock out given a certain order quantity. If the demand is normally distributed, you can find z as described in the earlier Continuous review section.

After you find z, use this equation to determine the optimal quantity to order:

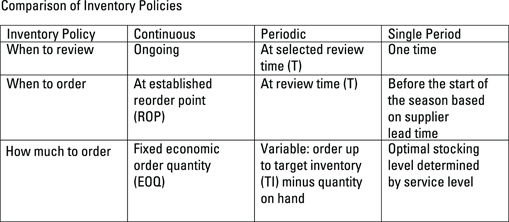

Comparing the options

A company may want to use more than one review process depending on the nature of the products they need to purchase. Figure 8-4 presents a side-by-side comparison of the three inventory review policies.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-4: Comparison of inventory policies.

Getting Baseline Data on Performance

How effective is your inventory management process? In this section we provide common metrics used to measure how well a company is controlling inventory levels and meeting customer demand.

Assessing the inventory management system

To find out how well an organization is managing its inventory, you must be able to measure it. Here are some common inventory metrics:

Average inventory level: As the name implies, this is the average inventory levels maintained in the system. Your goal is to reduce this without negatively impacting the other metrics.

Average inventory level: As the name implies, this is the average inventory levels maintained in the system. Your goal is to reduce this without negatively impacting the other metrics.

Line item fill rate: This is the total number of line items filled divided by the total number of line items. This metric applies to products or orders that contain multiple products. Again, you want this as high as possible without sacrificing average inventory levels.

Line item fill rate: This is the total number of line items filled divided by the total number of line items. This metric applies to products or orders that contain multiple products. Again, you want this as high as possible without sacrificing average inventory levels.

Order fill rate: This is the number of orders filled on time divided by the total number of orders during a time period. You want this to be as close to 100 percent as possible. Order fill rate and average inventory levels can be conflicting. Trying to maintain a high fill rate typically means maintaining more inventory.

Order fill rate: This is the number of orders filled on time divided by the total number of orders during a time period. You want this to be as close to 100 percent as possible. Order fill rate and average inventory levels can be conflicting. Trying to maintain a high fill rate typically means maintaining more inventory.

Service level: This represents the likelihood of having available stock in a replenishment cycle. You use the service level to calculate the safety stock in the inventory models. You usually set this value based on your customer expectations.

Service level: This represents the likelihood of having available stock in a replenishment cycle. You use the service level to calculate the safety stock in the inventory models. You usually set this value based on your customer expectations.

Turnover ratio: This ratio tells you whether average inventory levels are in line with sales. Calculate turnover by dividing annual sales by average inventory level. You typically want this number to be large. For example, a ratio of 5 means that your sales are 5 times greater than your average inventory levels. In this case, many operations managers say they’re carrying 5 turns of inventory.

Turnover ratio: This ratio tells you whether average inventory levels are in line with sales. Calculate turnover by dividing annual sales by average inventory level. You typically want this number to be large. For example, a ratio of 5 means that your sales are 5 times greater than your average inventory levels. In this case, many operations managers say they’re carrying 5 turns of inventory.

Many industries publish the average turnover ratio for companies in the industry. This allows firms to compare their performance to their competitors. If your ratio is lower than your competition’s, then the other companies are doing a better job of keeping their inventory levels low.

The inverse of the ratio gives you the average time period of supply on hand. If a company has a turnover ratio of 6, for example, it has, on average, 2 months of inventory in stock.

Evaluating the quality of customer service

As a manager, knowing how many customers you’re serving, particularly in context of how many you’re sending away, is extremely helpful. The ratio of sales (how many products you sold) to demand (how many customers wanted to buy) provides a much better picture of how you’re satisfying customers than the service level does.

The term service level is thrown around by operation managers, but it doesn’t exactly represent what it seems to. The service level tells you only how likely it is that you’ll have inventory on hand for all the customers who want it. For instance, a company that sets it service level at 95 percent has a 5 percent probability of running out of inventory. But this doesn’t mean that you’ll disappoint 5 percent of your customers by not having inventory.

The service level also tells you nothing about when the stock out will occur, and this matters. Experiencing a stock out just before a new shipment arrives or during the last days of the season isn’t as damaging as stocking out just after you place an order or midway through the season. The service level number doesn’t account for the fact that if you do stock out at some point, you’ve potentially still served many, if not most, of your customers. Therefore, the number always underestimates how many customers you’re actually serving, sometimes significantly.

A better measure of customer service is fill rate, or how many customers you serve on average (expected sales) as a percentage of the average number of customers who want your goods (expected demand). Here’s an equation to calculate your fill rate:

Depending on what inventory review system you use (single period, periodic, or continuous), the process of calculating the fill rate varies a bit.

Single period review

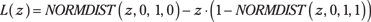

If your demand is normally distributed, expected sales are a function of the z you use to calculate your order quantity. (See the section Single period review earlier in this chapter.) Solve for L(z) to discover the number of sales lost due to inventory stock outs in relation to the standard deviation of demand:

To find L(z), program the following function into Excel or a similar spreadsheet program:

See Figure 8-5 for values for L(z) for some common service levels.

After you solve for L(z), you can find the fill rate using this formula:

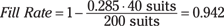

For example, if the service level for a swimwear company is 60 percent and the expected demand is 200 bathing suits, with a standard deviation of demand of 40 bathing suits, you can find the fill rate with this process:

1. A service rate of 60 percent corresponds to an L(z) of 0.285.

2. Calculate fill rate using this equation:

3. In this case, 94.2 percent of customers can be satisfied from inventory, and only 5.8 percent (100 – 94.2) of customers arrive to find no inventory on hand to fill their demand.

Note that the fill rate of 94.2 percent is significantly greater than the 60 percent service level.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-5: L(z) values for common service levels.

Continuous review

Under a continuous review policy, the odds of a customer arriving during a stock out are considerably less than in the other policies because the only time a stock out can occur is between the time a reorder of inventory is placed and when it arrives.

In this case, you calculate the L(z) the same as you do in the single period review, but you calculate the fill rate to account for the lead time:

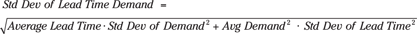

1. First, find the standard deviation of demand during the lead time:

2. Now calculate the fill rate using this formula, where LT is the lead time, D is the average demand, and EOQ is the economic order quantity:

Periodic review

Calculating the fill rate when using a periodic review policy is similar to the process for figuring fill rate for a single review policy, but finding the exact fill rate in this case is extremely difficult. You can get a reasonably accurate approximation by using a modified version of the single period equation:

1. Find the standard deviation of the demand over the lead time:

2. Use the value of the standard deviation of the demand in the following formula, which is essentially the single period fill rate formula:

Reducing Inventory without Sacrificing Customer Service

A company’s financial health depends on its ability to reduce inventory, but its viability as a business relies on doing so without sacrificing credibility as a supplier and its customer service. Accomplishing inventory reduction in customer-friendly ways requires well-designed processes (covered in Part 1), accurate demand forecasting (see Chapter 6), implementation of lean strategies (flip to Chapter 11), and production of quality products (turn to Chapter 13). Just as waiting is undesirable to customers in service operations, as shown in Chapter 7, waiting for a product to become available can be devastating to your business. Customers may cancel their order and buy elsewhere, and your business may lose those customers for good.

In this section, we point out how to use commonality and postponement strategies to reduce inventory levels without sacrificing customer service.

Multitasking inventory: The commonality approach

A manufacturer producing several products made from multiple components can reduce its overall inventory levels by using each component in more than one product. For instance, a major automobile manufacturer uses up to 85 percent of the same components in its luxury model and its economy name plate. By reducing overall demand variability for the component, the company reduces inventory requirements.

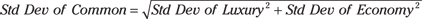

To put this in practical terms, let’s say that the demand variability for the luxury vehicle is 20 cars per week and the demand variability for the economy model is 10 cars per week. If each model utilizes its own ignition switch and the company strives to maintain a service level of 98 percent, then z equals 2.05 from the normal distribution curve.

If you assume that lead time is 1 day, the safety stock (SS) needed for each model would be as follows:

Total SS for switches is 61.5 (41 + 20.5), or 62 switches.

If the company can use a common switch for both cars, then the combined standard deviation for the switch would be

The safety stock for the common switch would be

By using the same components across multiple models, known as commonality, the manufacturer can reduce inventory. In the car example, the number of switches needed is reduced by 16, or about 26 percent, and the company can still maintain the original service level with this lower level of inventory.

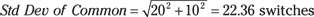

Holding on: The postponement strategy

By delaying product differentiation or customization for specific customer requests, a company can provide products according to buyer specifications while reducing overall inventory levels. Postponement involves strategically placing work-in-process inventory in the pipeline before customization points.

In addition to reducing inventory levels, postponement holds inventory in the state of lowest possible cost and reduces customer lead time for custom products. Postponement must be a consideration inherent in product design, and the benefits of postponement require a commonality strategy.

For example, consider a company that manufactures three different models of Super Dog action figures. Through the use of commonality, the models are the same except for their exterior armor and color. The non-optimized manufacturing process is illustrated in Figure 8-6.

Assume these conditions for this sample scenario:

Daily demand for each action figure stays at 100 with a standard deviation of 10.

Daily demand for each action figure stays at 100 with a standard deviation of 10.

The firm desires a 95 percent service level (Z = 1.64).

The firm desires a 95 percent service level (Z = 1.64).

Total lead time from start to FGI is 0.4 days.

Total lead time from start to FGI is 0.4 days.

In this case, the safety stock of the FGI for each action figure needs to be

Total FGI for the three models is 11 x 3 = 33 total items.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-6: Manufacturing without postponement.

If, however, the company implements a postponement strategy and delays customization by holding common dog figures in a WIP prior to attaching armor, as illustrated in Figure 8-7, the lead time to assemble the common models reduces to 0.3 days and the lead time from the WIP to FGI for each item becomes 0.1 days. The amount of safety stock in each of the three FGIs becomes

The total FGI for the three models is now 6 x 3 = 18 dogs.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-7: Manufacturing with postponement.

Employing a postponement strategy can reduce the amount of inventory in finished goods and protect a company against variability in demand for an individual product. The finished goods inventory drops from 33 dogs to 18 dogs with the implementation of a postponement strategy. If the customization lead time is small enough, the firm may consider not customizing the product until a customer order is received, thereby eliminating the need for an FGI altogether. Find ideas on how to reduce lead time in Part I of this book.

Managing Inventory across the Supply Chain

So far this chapter has focused on managing inventory within an individual firm. However, cost-effective inventory management also involves looking at total inventory across your entire supply line. After all, you do eventually pay for the excess inventory your supply holds or pay if your supplier stocks out and can’t supply you the parts you need in a timely manner. In this section we show you how important the entire supply chain of inventory is. (For details on the ins and outs of managing other aspects of the supply chain, see Chapter 10.)

Keeping track of the pipeline inventory

When assessing inventory, a firm not only has to take into account the inventory it has on-hand but also needs to be aware of the inventory being held by its suppliers. Figure 8-8 shows the typical supply chain for a product. Let’s assume that you’re the maker of an end product (OEM), and you purchase a subassembly for your product from supplier T1. T1 purchases components for the subassembly from T2, and T2 purchases raw materials for the component from T3. Your inventory costs are determined by how well you manage your on-site inventory and also by how well your suppliers manage their inventory levels. Inventory in the supply chain is often referred to as pipeline inventory because it will eventually emerge out the end.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-8: Supply chain inventory.

Unfortunately, managing this pipeline inventory isn’t an easy task and involves coordination across an often diverse supply chain. (See Chapter 10 for more on supply chain management.) Two important questions that a firm needs to address are where in the pipeline to hold inventory and how much should be at each stocking point. Answers to these questions vary based on production and shipping lead times.

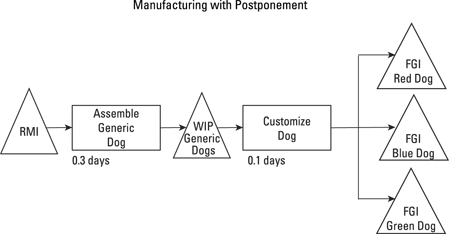

Some techniques can be used to manage supply chain inventory if the inventory costs across the chain are accounted for. Figure 8-9 illustrates a firm that buys a component from a supplier. The buying firm has a setup cost of $100 to order and a holding cost of $10 per component per year. The supplier produces the component only when an order from the buyer is placed and ships the component as soon as it’s manufactured, and thus, the supplier has no holding cost for the final component. The supplier, however, incurs a $300 per-order setup cost.

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-9: Optimizing supply chain inventory.

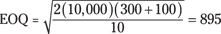

If the buying firm only looks to optimize its costs and uses an EOQ model with annual demand of 10,000 per year, then it would place an order for (to simplify the example we assume a constant demand):

You can calculate total supply chain inventory costs by multiplying the sum of the average inventory (EOQ/2) times the annual holding cost per unit, plus the number of orders place per year (D/EOQ) times the setup cost per order. Given an EOQ of 448, total supply chain cost would be

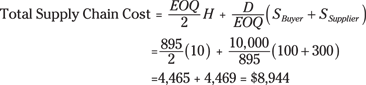

However, if you optimize taking into account the supplier’s costs when determining your EOQ, your new recommended order quantity is

Total supply chain costs then become

In this example, you can reduce your total supply chain inventory costs by $2,225 ($11,169 – $8,944), or approximately 20 percent. As you can see, being aware of all inventory costs across your supply chain can lead to significant savings.

Setting service levels with multiple suppliers

As if setting service levels isn’t hard enough with one supplier, doing so is even more difficult if you have multiple suppliers providing materials that all must go into your product. Figure 8-10 shows a manufacturer that has multiple suppliers. (For more on the tiered structure of a supply chain, see Chapter 10.) If the OEM sets a service level of 98 percent for each of its suppliers, then the end service level will be much lower at 90 percent. In general, the end product service level is calculated as

Illustration by Wiley, Composition Services Graphics

Figure 8-10: Service levels across the supply chain.

This lower-end product service level occurs because each supplier has a 2 percent chance of stocking out, and you can’t produce your product unless you have product from every supplier. As you can imagine, the more suppliers you have, the higher your individual service levels must be to maintain an acceptable end product service level.

Successfully balancing inventory with actual customer demand minimizes the risks of losing sales to the competition and of overinvesting in unneeded inventory.

Successfully balancing inventory with actual customer demand minimizes the risks of losing sales to the competition and of overinvesting in unneeded inventory. Make sure to express SL as a decimal when entering this value into Excel. In other words, use 0.95, not 95 percent, because this is standard Excel notation.

Make sure to express SL as a decimal when entering this value into Excel. In other words, use 0.95, not 95 percent, because this is standard Excel notation.