30.1 Introduction

Research and policy development relating to biological invasions accelerated rapidly in most parts of the world in the late 1980s, following a major international programme on biological invasions conducted under the auspices of the Scientific Committee on Problems of the Environment (SCOPE) (Simberloff 2011). South Africa played an important part in the SCOPE programme, contributing a national synthesis book and major inputs to several thematic projects (van Wilgen 2020, Chap. 2). As was the case worldwide, research on biological invasions in the post-SCOPE era in South Africa was done mainly by individual researchers or small groups working in diverse academic and agency institutions.

There was a major upsurge of interest in research on invasions in South Africa in the mid-1990s, much of it associated with the launching, in 1995, of the Working for Water programme , a public works programme for removing invasive plants from catchments to increase water yields and restore biodiversity (van Wilgen et al. 2011). This was a time of rapid change in all spheres of life in South Africa, following the end of apartheid and the country’s first democratic elections in 1994. Important changes were also made to the way that government science funding was allocated at this time.

The publication of a White Paper on Science and Technology in 1996, and the establishment in 1999 of the Department of Science and Technology (DST) to replace the former Department of Arts, Culture, Science and Technology were key events in the restructuring of the science landscape. The DST introduced the ‘National System of Innovation’ (NSI) and in 2002 launched South Africa’s National Research and Development Strategy. Among other ideas, this strategy proposed the establishment of “networks and centres of excellence” with the aim of “achiev[ing] national excellence by “focus[sing] … basic science on areas where we are most likely to succeed because of important natural or knowledge advantages.” The Strategy also contained plans “to draw young people towards careers in scientific research and to ensure that such careers are sustainable.” There were also requirements to establish a “critical mass to generate sufficient high-quality research to make an impact on the global stage” and to “focus strongly on human resource development and on popularising science”. An important outcome of the strategy was the first call, in 2003, for applications for national Centres of Excellence (CoEs) by the National Research Foundation (NRF ; the intermediary agency between the policies and strategies of the South African Government and the country’s research institutions).

The application for a national “Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology” focused on the need for coordinated research and capacity-building in the field of invasion biology in South Africa, given the interest and importance mentioned above. The proposal reviewed the major and growing impacts of invasive species on the country’s natural capital and ecosystem services , and stressed that poor people in rural areas were particularly adversely affected by invasions through loss of productive land, reduced water catchment yields, the harmful effects of toxic invasive species, and other factors. It also outlined features that make South Africa a superb natural laboratory for the study of biological invasions (see van Wilgen et al. 2020a, Chap. 1 for details). Across all disciplinary areas, 70 pre-proposals were received by the NRF, 13 full proposals were invited, and funding was awarded for six CoEs, of which the Centre for Invasion Biology was one. In 2004, the DST-NRF Centre of Excellence for Invasion Biology (hereafter, the Centre for Invasion Biology, the Centre, or the C∙I∙B) was launched with its headquarters at Stellenbosch University, where the Director and most of the core team were based, and which offered the academic and administrative support associated with a leading research-intensive university (many of the core team of researchers are based at other South African universities and other research institutions). Having the C∙I∙B headquarters in the Western Cape was justified because this region receives the largest investment on alien species management, thanks mainly to the massive invasions of woody plants in the Fynbos Biome . Funding of the C∙I∙B in the face of demands to address many post-apartheid challenges in a developing country context was a recognition of biological invasions as a major challenge to South Africa’s environmental health, and also the opportunities to make major contributions in the rapidly growing field of invasion science. In its 15-year history, the C∙I∙B has become a significant provider of research, skilled capacity, and policy advice to the South African government in the field of biological invasions.

This chapter reviews how the structure and functioning of the C∙I∙B has evolved over time and outlines the main achievements and challenges in each of its key performance areas. We first discuss the guiding principles that have governed the functioning and operation of the C∙I∙B in the 15 years of its existence and then turn to successes and challenges that provide pointers to the way forward.

30.2 Guiding Principles

Research;

Education and training;

Networking;

Information brokerage; and

Service provision.

embracing interdisciplinarity, actively seeking out expert partners in diverse fields relevant to invasion science;

contributing to the international knowledge base while remaining locally relevant (most work was therefore done within South Africa);

improving the understanding of the functioning of South Africa’s ecosystems to inform efforts to respond effectively to changes;

bridging the gap between the natural and social sciences;

being policy-relevant;

focusing primarily on key issues relating to biological invasions in natural and semi-natural ecosystems in freshwater, marine, and terrestrial ecosystems (i.e. excluding agroecosystems), but also giving limited attention to other facets of global change and general biodiversity;

seeking to complement other initiatives already underway in the country (e.g. biological control and disease ecology were explicitly excluded as core focus areas, but synergies were sought with researchers in these fields).

The C·I·B has sought to function as an independent “honest broker” (sensu Pielke 2007) of information that could facilitate the objective framing of problems, and provide the means for the evaluation of potential outcomes of different intervention options, rather than to be an advocate for any particular option. This has been an important guiding principle; it has meant that C·I·B members have been able to study the conflicts of interest that are a key part of invasion science (e.g. van Wilgen and Richardson 2012; Woodford et al. 2016; Zengeya et al. 2017, 2020; Novoa et al. 2018; Davies et al. 2020), and through their understanding lead the way toward resolutions, without “taking a stand” on any particular option. The term “invasion science” (the core business of the C·I·B) describes the full spectrum of fields of enquiry pertaining to alien species and biological invasions. It embraces invasion biology and ecology, but increasingly draws on non-biological fields, including economics, history, ethics, sociology, and inter- and transdisciplinary studies (Richardson 2011a).

A crucial requirement of the CoE mandate was to achieve demographic transformation by changing the race and gender profile of students and researchers to be more representative of the South African population, in line with the broad government intention to redress decades of apartheid policy. The C·I·B has thus actively sought to attract staff, students, and team members from previously disadvantaged groups.

The C·I·B has functioned as an inclusive distributed network, or a “network of networks” (see Sect. 30.3.3), with the aim of drawing together all available expertise in fields relevant to biological invasions. The Centre reports twice a year to the DSI and NRF through its Steering Committee (SC; initially an Advisory Board) which comprises representatives of DSI, NRF, Stellenbosch University, and two to three partner organisations. The Steering Committee also includes two international science advisers who attend the annual research meeting of the C·I·B and report to the Steering Committee Chair on the scientific standard of activities of the Centre from an international perspective. One SC member was a social science advisor whose brief was to advise the Centre on opportunities and priorities for work in this field. At the centre of C·I·B operations is its Core Team, which initially comprised 14 selected researchers working on multiple aspects of invasions, and who were based at South African academic institutions and so could supervise students. A small number of members were based at parastatal research institutions such as the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research . The core team currently has a broader scope and includes 26 members, including several from non-academic organisations such as the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI) and South African National Parks (SANParks).

The structure of the C∙I∙B has changed over time. A second network of C·I·B Associates was formed in 2007, consisting of individuals based in South Africa who were either researchers or managers at non-academic institutions, or retired academics. This network was later expanded to include key international partners. A third network of “C·I·B Visiting Fellows” was added in 2014. Fellows are senior researchers based outside South Africa who visit the C·I·B for a month or more to collaborate with C·I·B team members. Visiting Fellows, of whom 13 had been supported by mid-2019, typically establish ongoing collaborations with C·I·B members, thereby extending the international reach of the Centre. Another network—C·I·B alumni—is increasingly contributing to Centre activities (see Sect. 30.3.3). In 2017, the Core Team was expanded to include managers in partner organisations to reflect the increasing importance of operational research. Since the salaries of most Core Team members are covered by their employer organisations, and members receive only a moderate annual incentive grant from the C·I·B, the Centre’s activities form only a part (in some cases a small part) of the work programme of most Core Team members. This limits the extent to which research directions can be prescribed, although the allocation of student bursaries ensures alignment with the C·I·B’s Mission. Five Core Team members have held Research Chairs as part of the South African Research Chairs Initiative (SARChI) which is another funding instrument of the NRF. These Chairs have strengthened opportunities for networking and for drawing in expertise in key areas aligned to the C·I·B’s Mission. The Chairs focus on biodiversity issues in particular geographic regions (the Vhembe Biosphere Reserve; KwaZulu-Natal and the Eastern Cape ) and fields of study (Land Use Planning and Management; Inland Fisheries and Freshwater Ecology; and Mathematical and Theoretical Physical Biosciences).

Two conceptual frameworks that have guided investments and activities in the Centre for Invasion Biology between 2004 and 2019. B is reproduced from van Wilgen et al. (2014) with permission of the Academy of Science of South Africa

30.3 Achievements in Key Performance Areas

This section describes progress in addressing the Centre’s key performance areas (KPAs): research; education and training; networking; information brokerage; and service provision.

30.3.1 Research

In the framework for the establishment of DST-NRF Centres of Excellence in 2004, the DST and NRF required the Centre to focus on research as its main activity. It specified that “the work that is undertaken should be focused on the creation and development of new knowledge and technology. A Centre of Excellence should focus on niche knowledge area, or field, in which it commands exceptional expertise and comparative advantage over other research institutions or centres”. Here we provide a brief overview of how the C·I·B has gone about achieving that focus with particular reference to publications in scholarly journals.

Between the inception of the C·I·B in 2004 and the end of 2018, 1745 peer-reviewed papers with C·I·B-affiliated authors were published in journals listed on the Web of Science. The DST-NRF set the C·I·B an annual target of 60 (2004–2014) and 85 (2015 onwards) papers published annually; this has consistently been exceeded; for example, 201, 216 and 162 papers were published in 2016, 2017 and 2018, respectively. Of papers published from 2004 to 2018, 987 (57%) can be categorised as core contributions to invasion science, while the remainder address diverse “biodiversity foundations” topics. Of the 987 contributions to invasion science, most (83%) deal with invasion biology and ecology (the “nuts and bolts” of invasions sensu Richardson 2011a, b), while 17% of papers focussed primarily on the management of biological invasions. The scientific impact of these papers is reflected in 42,608 citations in Web of Science and an h-index of 89 (i.e. 89 papers have been cited 89 or more times each). Although we have no benchmark against which to compare the relative productivity of the C·I·B, it is clear that the Centre has made a substantial contribution both nationally and internationally. For example, between 2004 and 2017, the C·I·B contributed 50 out of 460 (11%) of invasion biology-related papers to the journal Diversity and Distributions, 10 out of 37 (27%) of papers to the journal NeoBiota, and 60 out of 1597 (4%) of papers to the journal Biological Invasions.

For papers published in Biological Invasions (the flagship journal of invasion science) between 2004 and 2018, the C·I·B ranked fourth among funding agencies acknowledged in publications (after the National Science Foundation, USA; the Australian Research Council; and the National Natural Science Foundation of China). Stellenbosch University was also ranked fourth in terms of organisations in the addresses of papers (after the US Geological Survey; University of California, Davis; and Spain’s Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas). C·I·B-affiliated researchers occupied the first two places in terms of numbers of papers published (D.M. Richardson—40 papers; P. Pyšek—27 papers). At a national scale, as may be expected, the relative contribution was much higher, with the C·I·B contributing 67%, 62% and 49% of invasion biology-related papers in African Journal of Marine Science, Bothalia, and South African Journal of Botany respectively.

Besides peer-reviewed journal articles, C·I·B activities have led to the production of several volumes and journal special issues synthesising a diversity of themes in invasion science (see Sect. 30.3.3). Many non-technical texts were produced that helped to raise awareness of invasive species issues among a wider audience (van Wilgen et al. 2014).

Fields of research within the discipline of invasion science, and brief descriptions of key contributions to the development of those fields by the Centre for Invasion Biology (C·I·B)

Element of framework | Field of research | Brief description of C·I·B contributions |

|---|---|---|

Patterns and processes of invasion | Pathways of species introduction | The C·I·B has conceptualised the role of dispersal pathways (notably the contributions of propagule pressure , genetic diversity and the potential for simultaneous movement of co-evolved species) in determining the success of introductions of species to new regions. Research at the C·I·B has also shed light on the dynamics of introduction and dissemination of a range of organisms and different spatial scales in detail, notably for ants, marine organisms, reptiles, amphibians, and plants (especially Australian Acacia species, and the roles of horticulture, biofuels, roads and rivers) [7, 12]. |

Determinants of success of species establishment | Research at the C·I·B has advanced the understanding of factors that mediate invasion success for numerous groups, including birds, terrestrial invertebrates, and vascular plants [13, 14]. Such work has provided key insights for assessing the risk of further introductions [20]. Phenotypic plasticity (the capacity of organisms to change their phenotype in response to changes in the environment) has been explored mainly for invertebrates, but also for plants. | |

Patterns and mechanisms of species expansion and spread | Understanding how alien species spread is crucial for developing appropriate management responses. Macroecological studies have explored the relationship between native and alien species diversity, and the link between human population density and alien species distributions [3]. Studies have also elucidated the invasion dynamics and options for management for birds [5], marine organisms [9], reptiles [5], amphibians [5], and terrestrial plants. The role of propagule pressure in mediating invasions has been explored in many studies, covering many taxa and contexts. | |

Impacts of invasions on biodiversity patterns and processes, and ecosystem functioning | Many invasive alien species have serious negative impacts on biodiversity and ecosystem services [15, 17]. The C·I·B has made substantial contributions in this area, ranging from local to national scales. These included studies on Marion Island [8], in Fynbos, Karoo [16] and Savanna Biomes , and in freshwater [6] and marine ecosystems [9]. | |

Management and remediation of impacts | Preventing the introduction of new invasive species | One of the most effective ways to reduce the risk of biological invasions is to stop them before they happen, by preventing high-risk species from entering the country, or by intercepting them at the border. Many C·I·B studies have contributed knowledge to inform screening systems to identify species that pose a high risk of invading South African ecosystems [20]. |

Removing newly-established populations of potentially harmful invasive species | If populations of invasive alien species are detected early, eradication can be considered. The C·I·B has studied several invasive plant species that still have limited distributions and where eradication is potentially feasible [21]. | |

Reducing impacts and ecosystem restoration | Considerable attention has been given to developing sustainable protocols for restoring ecosystems following the removal of invasive species [23]. Key insights for restoring fynbos and riparian communities after the clearing of invasive trees have emerged from the C·I·B’s work. The overall effectiveness of national-scale alien plant clearing programmes has also been assessed [19, 21]. | |

Monitoring the extent and impacts of widespread invasive species | Once alien species have come to dominate ecosystems, management options are reduced. It is important to be able to identify such areas. Remote sensing and other methods have been applied to map, assess and monitor the extent of invasions, and standardised metrics have been proposed [27]. | |

Policy development | Policy formulation | Work at the C·I·B is intended to lead to knowledge that will underpin the development of sound policies for management [11, 12, 21, 22, 28, 30]. The C·I·B has published accounts of frameworks or protocols for prioritising invasive species and/or areas for management based on the evaluation of their impacts and/or other considerations [30]. The C·I·B has also played a key role in developing legal regulations for the management of invasive species, and in the drafting of a national strategy for dealing with biological invasions in South Africa [1, 18]. |

Risk assessments | Formal risk assessments (RAs) are a central component of policies and legislation for the management of invasive species. The C·I·B has contributed to the conceptual development of risk assessment methodologies for invasive species management, and to the implementation of RAs for specific applications in South Africa [20]. | |

Overarching research | Biological foundations | Understanding the impacts of invasive species demands a fundamental understanding of the functioning of the ecosystems they invade and the diverse drivers of change in these systems, as well as the interactions and synergies between these drivers. To this end, the C·I·B has conducted many studies have contributed to the improved understanding of South African ecosystems [30]. |

Human dimensions | Many studies have addressed the numerous ways in which human requirements drive introductions of alien species, and how humans perceive alien and invasive species and rationalise the need to manage invasions and the options for doing so [24]. Studies have examined the drivers of invasions, including commercial forestry, the pet and nursery trade, and recreational angling. Several case studies have been exploited to elucidate the range of human perceptions pertaining to invasive species and options for their management, which is especially challenging when invasive species (such as trout or trees used in commercial forestry) also have commercial or other value [4]. | |

Basic inventories | Many studies have contributed to inventories and species lists for a range of native taxa and ecosystems. Other contributions have been based on detailed surveys of marine ecosystems , the application of molecular methods to detect cryptic species, an assessment of cryptogenic marine species, studies to resolve questions of species identification, and the combination of meticulous field surveys, interviews and the examination of introduction records and collections. DNA barcoding has emerged as an important tool for resolving a range of species identification issues in invasion biology. | |

Development of a modelling capability | Many types of models have been developed and used the study of different aspects of invasion science . These include models used in theoretical analyses of evolutionary processes, population dynamics, through to models applied to provide support to management. Many studies have applied bioclimatic, species distribution or niche-based modelling. |

Networks of connectivity for authors affiliated with the Centre for Invasion Biology in 1711 publications from 2004 to 2018. Network A: Taxonomic groups are shown in different colours (key: blue: plants; yellow: invertebrates; green: mammals; purple: marine organisms; pink: freshwater organisms; grey: amphibians; dark grey: reptiles; white: all species). White shapes indicate papers dealing with general invasion literature applicable to all species. Triangles show the 57% of C∙I∙B publications on invasions, while circles are “foundational biodiversity” publications. B shows the same network with only invasion-focussed research articles (triangles). Research articles are shown in blue, while those focussing on management are in green. Those that deal with both research and management are shown in red

Once the 43% of papers with diverse “biodiversity foundations” topics are removed, the taxonomic disparities in the author networks begin to dissolve (Fig. 30.2b). There is an obvious bias in the publications by C∙I∙B authors towards management topics on alien plants, with some authors dealing almost exclusively with this topic. Despite papers with a management focus being relatively slim for other taxa, the number of papers dealing with management of freshwater fishes is growing (see Weyl et al. 2020, Chap. 6). This bias away from research on the management of animal invasions likely reflects the absence of South African legislation pertaining to these taxa until relatively recently (Lukey and Hall 2020, Chap. 18; Davies et al. 2020, Chap. 22). We might therefore expect this aspect of the literature among C∙I∙B authors to grow in the future.

30.3.2 Education and Training

In the framework for the establishment of DST-NRF Centres of Excellence, the DST and NRF required CoEs to develop human capacity by focussing on support for post-graduate (honours, masters and doctoral) students, post-doctoral fellows, interns and research staff. This activity was explicitly required to include support for students to study abroad, and to undertake joint ventures in student training. The human capital development efforts were required to “target the development of high-level scarce skills in the relevant disciplines within specialised fields of knowledge”. In creating, broadening and deepening research capacity, Centres of Excellence were required to “pay particular attention to racial and gender disparities”. The inputs, outputs and outcomes of this activity are discussed sequentially below.

The South African research landscape has changed dramatically since the establishment of a democratic government in 1994 (Department of Science and Technology 2017). The CoEs have been in existence for much of this period since they were established in 2004. Along with an expansion of funding instruments available to researchers such as the SARChI chairs programme, the Thuthuka Programme aimed at early career researchers, and the THRIP programme for industry/higher education partnerships, and partly as a result of the government target of one PhD graduate per 10,000 of population (Department of Science and Technology 2008; see Byrne et al. 2020, Chap. 25), enrolments at the PhD level have increased. In response, the C∙I∙B has strongly emphasised student training and capacity-building, specifically the quality and throughput rates of post-graduate students (bachelor with honours, masters and doctoral degrees).

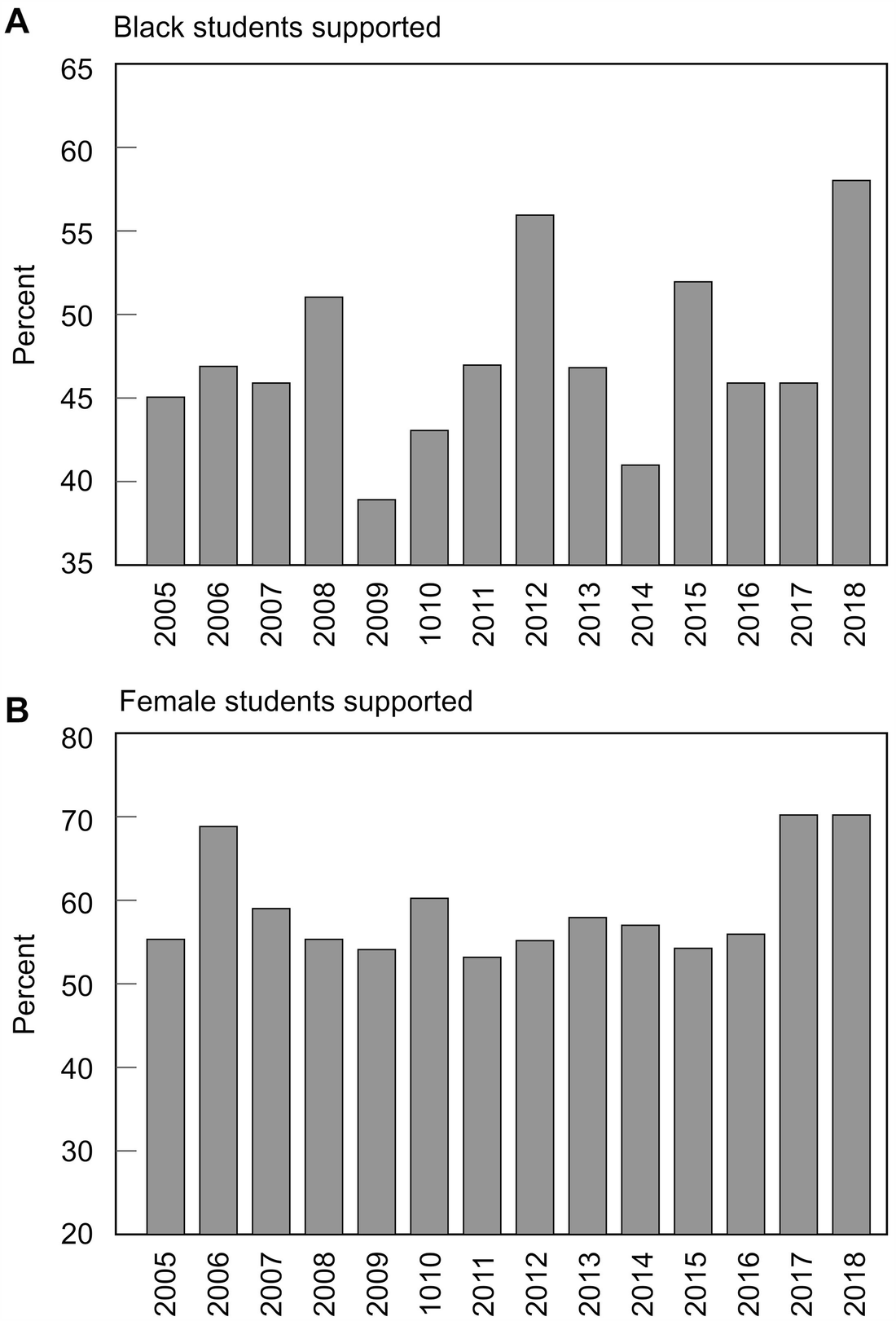

Demographic targets and metrics for the C∙I∙B’s entire history (2005–2018) showing percentage of black students (a) and percentage of women students (b). The Centre’s service level agreement with its principal funders imposes a target of 50% black students and 50% female students

The C∙I∙B runs two bursary programmes, one that is accessible to students who apply to study under supervision of a Core Team member at a partner university, and the other that is open to all post-graduate students working on any invasion-related subject, who can receive a bursary to work with any researcher located at any academic institution nationwide. The ‘open bursary programme’ has produced 27 graduates, including six PhDs. In some cases, the collaborations established with the open programme bursars and supervisors have resulted in productive longer-term research partnerships, thereby widening the C∙I∙B’s network. All fully-funded bursars receive the same level of funding at competitive rates established by the NRF, unless otherwise specified by an external funder, and project running costs are supported by a separate grant paid to the supervisor.

Bursaries and post-doctoral salary support are offered to applicants if they are aligned with, or contribute to, the C∙I∙B’s equity targets expressed in its service-level agreement with the NRF, the C∙I∙B’s Vision and Mission, and its strategic and business plans. In addition, the C∙I∙B’s bursary panel takes into account synergies with the programmes of partner organisations such as SANBI , SANParks , and the SARChI initiative of the NRF, and provincial nature conservation agencies and local municipalities, and attempts to achieve equity among regions and terrestrial, freshwater and marine realms.

Up to the end of 2018, 64 PhDs have been awarded, and 67 post-docs have been supported through the C∙I∙B. Sixty two percent of students and post-docs were registered at Stellenbosch University, and the remainder at 15 other South African universities. Most students published at least one peer-reviewed paper in an ISI accredited journal; for instance, 76% of PhD students published at least one (maximum: 5) papers during their degrees or in the two years following graduation. The diversity of opportunities to communicate their research to peers and the public has resulted in awards and recognition in competitions open to students. For example, over the past four years (2016–2019) C∙I∙B students have participated in training courses and competitions for science communication such as the Fame Lab, and received prizes and awards at institutional, national and international academic meetings.

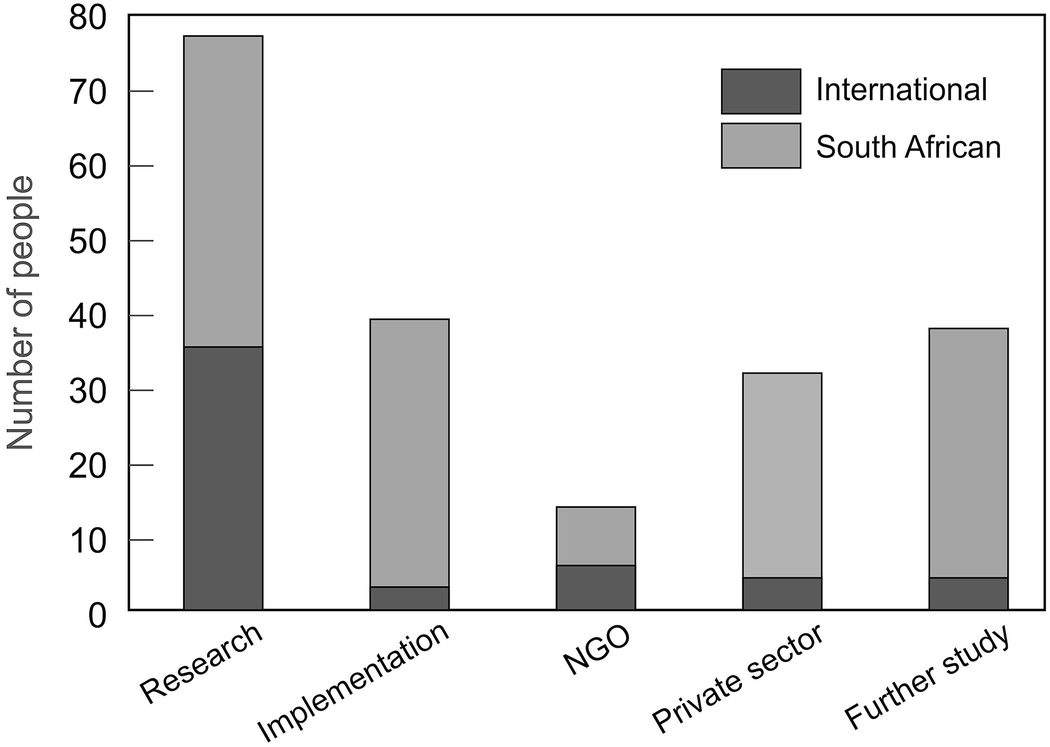

Many alumni maintain contact with the C∙I∙B or continue to work with C∙I∙B members in various capacities, and the Centre maintains a database of the whereabouts of alumni. Of those alumni whose whereabouts are known, 19% are not in any employment because they are studying further. The majority (39%) are located in academic and research organisations, 20% are in government and implementing agencies, 16% work in the private sector, including consultancies, and 7% are working for NGOs, locally or abroad.

Distribution of alumni of the Centre for Invasion Biology in employment sectors: Research—academic and research organisations such as universities and science councils; Implementation—government and implementing agencies at national, provincial or local (municipal) level; NGO—non-government organisations; Private—private sector companies and consultancies

A 2019 survey of C∙I∙B alumni elicited response from 70 people (32%), 80% of whom said that their experience of invasion biology (obtained through their association with the C∙I∙B) was relevant (at least partly) to their current area of work, with 73% of their current work associated with biological invasions. Although most C∙I∙B alumni are involved with universities (48%), many are employed by government, science councils or government implementing agencies which are involved with biodiversity management (27%).

The C∙I∙B has taken a ‘pipeline’ approach to student training, which seeks to attract promising students to the field of biological invasions research, and to retain them as long as possible to produce graduates who are sought after for their knowledge, their creative and critical thinking, and expertise. To this end, the C∙I∙B provides opportunities for students to network widely and this has led to student mobility within the network. Several students have studied alongside C∙I∙B members from undergraduate level through to PhD or post-doctoral level, moving through several nodes of the network to work with different supervisors and in different ecological systems. These early-career researchers have increased their exposure to a wide range of invasion science questions and techniques through the C∙I∙B’s training, networking, and science communication initiatives.

Changes in the status of students and post-doctoral associates within the C∙I∙B’s network

Initial status | Current status | Number of individuals |

|---|---|---|

Student | Core Team Member | 4 |

Student | Research Associate | 7 |

Post-doctoral Associate | Core Team Member | 6 |

Post-doctoral Associate | Research Associate | 7 |

30.3.3 Networking

In the framework for the establishment of DST-NRF Centres of Excellence, the DST-NRF required the Centre “to actively collaborate with reputable individuals, groups and institutions. Equally, it must negotiate and help realise national, regional, continental and international partnerships”. The C∙I∙B has actively established and maintained networks that allow it to maintain and build research excellence. Such networks also provide the means to interact directly with policy-makers, managers and practitioners to fulfil obligations on service provision (Sect. 30.3.5). The C∙I∙B model has shown that effective networking can enhance the relevance of academic research to a host of stakeholders. However, networking cannot be limitless, as it has relied on individual C∙I∙B members and their capacity to form and maintain productive working relationships. By making networking a mandatory KPA, the C∙I∙B has clearly become more relevant to more stakeholders than it would have been by simply relying on the normal academic networks of conferences and collaborations. Some of the main activities that have contributed to meeting this requirement are discussed in the next sections.

A network (transformed into a unimodal network using Gephi 0.9.1: Bastian et al. 2009) wherein the links represent collaboration/co-authorship of C∙I∙B articles between locations (based on authors addresses). Articles co-authored by C·I·B-affiliates over the period of 2004–2018 were used (n = 1711). To generate the networks showing the global reach of collaborations, data in the address field of the bibliographic records of the relevant articles were geocoded using Citespace (5.3.R4.8.31.2018) software (Chen 2004). Links between, C∙I∙B Core Team members and their collaborators (red circles), and the locations representing them are red. Links that represent collaborations between C∙I∙B Associates and their collaborators (white circles) are shown in blue. Of the 1115 articles (by 2779 authors, 52 countries) that were geocoded successfully, 881 articles involved at least one Core Team member as a co-author. Although a sizeable proportion of the articles analysed were not successfully geocoded, the resultant network clearly demonstrates the global reach of C·I·B collaborations. The lack of standardisation of addresses in the WoS address field, and software and geocoder limitations, pose some difficulties with automated geocoding processes in terms of both detection and its accuracy (Leydesdorff and Persson 2010; Bornmann and Ozimek 2012)

The ethos of inclusivity of the C∙I∙B is demonstrated by the collaborative links between Core Team members. The Centre started with 14 Core Team members and has built on this steadily over its 15-year history; in 2019 the Core Team had 26 members. Five of the original Core Team have remained throughout the period, although this includes two retirees who now have Emeritus status. Since 2004, 41 South African researchers have been members of the C∙I∙B Core Team; members have been spread across 15 different South African institutions, including eight of the country’s universities and seven partner institutions.

The C∙I∙B is a partner to several government institutions that are legislatively mandated to manage invasive species. These include the national environmental authority [DEFF, principally, though not exclusively, through the Natural Resources Management Programme in its Environmental Programmes directorate (formerly the Working for Water programme ) and provincial environmental and conservation agencies (e.g. CapeNature in the Western Cape and the Department of Agricultural and Rural Development in Gauteng ) and local metropolitan municipalities (eThekwini [Durban ] and City of Cape Town]. SANParks and SANBI, both affiliates of DEFF, are also key partners; such partnerships allow the Centre to identify connections between research and implementation, and to gain valuable input to student training, field work opportunities and project ideas from SANParks and SANBI staff. Through these partnerships, the C∙I∙B supports established scientists working in these organisations (as Core Team members or Associates), promotes coordination of research into invasive species, and provides a forum for interaction and career development of young researchers and practitioners once they graduate. Advice given by team members informs management practices, and assists policy development. The C∙I∙B has a strong collaboration with the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity, a National Facility of the NRF, through which most C∙I∙B-funded work on invasions in freshwater ecosystems is conducted.

Both SANBI and the City of Cape Town have paid for personnel to be embedded within the C∙I∙B. SANBI staff have provided an invaluable and direct link between research at the C∙I∙B and government policy and management initiatives, thereby helping to achieve many of the Service Provision objectives of the centre. This has included work on “emerging invasive species” (as discussed by Wilson et al. 2013), where effective networking has drawn on the combined resources of SANBI and the C∙I∙B to gain new knowledge. Similarly, with respect to risk assessment science (Kumschick et al. 2020), obvious benefits have emerged from linking SANBI and C∙I∙B networks. Links with the City of Cape Town helped to formalise the often missing association between research and implementation (see Gaertner et al. 2016, 2017), especially in habitat restoration (see Mostert et al. 2018; Holmes et al. 2020), and urban invasions (see Potgieter et al. 2018, 2020, Chap. 11). Collaborations with both institutions started with formal memoranda of understanding, built around existing and new Associates of the C∙I∙B. Similar arrangements are being explored for municipalities in other parts of the country.

Examples of substantial focussed collaborations that have advanced understanding and raised awareness of biological invasions in South Africa

Subject | Initiative/product | Products | Issues addressed | Primary references |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Management of riparian ecosystems in invaded landscapes | National project and journal special issue on “Riparian vegetation management in landscapes invaded by alien plants: insights from South Africa” | 14 papers by 26 South African authors | The project produced guidelines and tools to improve management of invaded riparian ecosystems | Esler et al. (2008) |

Links between marine and terrestrial ecosystems in oceanic islands | Synthesis of collaborative research by the South African National Antarctic Programme and edited book on “Prince Edward Islands : Land-sea interactions in a changing ecosystem” | 14 chapters by 24 authors from seven countries | An overview of the structure, functioning and interactions of marine and terrestrial systems of the Prince Edward islands. Demonstrates how global challenges, including climate change , biological invasions and over-exploitation are playing out at regional and local levels in the Southern Ocean | Chown and Froneman (2008) |

Global synthesis of invasion ecology | International workshop and edited book on “Fifty years of invasion ecology” | 30 chapters by 51 authors from nine countries | A synthesis conference was hosted by the C·I·B to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Charles Elton’s classic book on the ecology of invasions by animals and plants. It examined the origins, foundations, current dimensions, and potential trajectories of invasion science | Richardson (2011b) |

Status of plant invasion ecology | International conference on plant invasions (EMAPi 10) and journal special issue entitled “Plant invasions: theoretical and practical challenges” | 15 papers by 48 authors from 10 countries | The Ecology and Management of Alien Plant Invasions (EMAPi) conference series is the premier international forum for this field. The C∙I∙B hosted the 2009 event which attracted 263 delegates from 29 countries. The journal special issue contains papers on advances and challenges in theoretical and practical dimensions of plant invasion science | Richardson et al. (2010) |

Ecology and management of introduced Australian Acacia species | International workshop and journal special issue on “Human-mediated introductions of Australian acacias—a global experiment in biogeography” | 21 papers by 112 authors from 14 countries | This compendium explored how evolutionary, ecological, historical and sociological factors interact to affect the distribution, usage, invasiveness and perceptions of a globally important group of plants | Richardson et al. (2011) |

Plant invasions in protected areas | International project and edited book on “Plant invasions in protected areas: Patterns, problems and challenges” | 28 chapters by 79 authors from 20 countries | The first comprehensive global review of alien plant invasions in protected areas, providing insights into advances in invasion ecology arising from work in protected areas. It provides practical guidelines for managers drawing on experience from around the world | |

Ecology and management of tree invasions | International workshop and journal special issue on “Tree invasions—patterns and processes, challenges and opportunities” | 16 papers by 36 authors from 12 countries | The special issue collates knowledge on tree invasions and identifies key challenges facing researchers and managers. Contributions span disciplines, geographic regions and taxa, and provide new insights on pathways and historical perspectives, detection and monitoring , determinants of invasiveness , function and impact, and the challenges facing managers | Richardson et al. (2014) |

Wicked problems in invasion science | International workshop on “Confronting the wicked problem of managing biological invasions” co-hosted by the C·I·B and the Canadian Aquatic Invasive Species Network; attended by 50 researchers, mainly from South Africa and Canada | One synthesis paper with 5 C·I·B-affiliated authors and 2 Canadian authors | Reviews the disconnect between the perception and reality of how “wicked” invasions are. Proposes an approach for dealing with “wickedness” in invasion science, by either recognising unavoidable wickedness, or circumventing it by seeking alternative management perspectives | Woodford et al. (2016) |

Insect invasion ecology | International workshop and journal special issue on “Drivers, impacts, mechanisms and adaptation in insect invasions” | 14 papers by 95 authors from 24 countries | The study of insect invasions has given scant attention to emerging hypotheses and theories in invasion science . The workshop and special issue set out to explore the current understanding of insect invasions with reference to key hypotheses | Hill et al. (2016) |

Evolutionary ecology of tree invasions | International workshop and journal special issue on “Evolutionary dynamics of tree invasions” | 13 papers by 45 authors from 10 countries | Synthesis of evolutionary dynamics of alien and invasive trees, including evolutionary mechanisms in tree genomes, to explore how such mechanisms can impact tree invasion processes and management | Hirsch et al. (2017) |

Biological invasions in urban ecosystems | International workshop and journal special issue on “Non-native species in urban environments: Patterns, processes, impacts and challenges” | 18 papers by 63 authors from 15 countries | The workshop and special issue reviewed the current understanding of invasions in urban settings to determine whether patterns and processes of urban invasions are different from invasions in other contexts. It sought insights on the special management needs for urban invasions and guidelines for bridging gaps between science, management, and policy for urban invasions | Gaertner et al. (2017) |

The status of biological invasions in South Africa | National workshop and journal special issue on “Assessing the status of biological invasions in South Africa” | 20 papers by 172 South African authors | The workshop and special issue collated information required for the first national status report on biological invasions in South Africa | Wilson et al. (2017) |

Engaging stakeholders in alien species management | National workshop on “Towards a framework for engaging stakeholders on the management of alien species” | One synthesis paper with 19 authors | Management of invasions is contentious when stakeholders who benefit from alien species are different from those who incur costs. Effective engagement with stakeholders is key to effective management. The workshop, subsequent consultations, and the paper developed a 12-step framework for such engagement | Novoa et al. (2018) |

The human dimensions of invasion science | International workshop and journal special issue on “The human and social dimensions of invasion science and management” | 18 papers by 66 authors from 18 countries | The workshop and special issue examined the relations between humans and biological invasions in terms of four crosscutting themes: how people cause biological invasions; how people conceptualise and perceive them; how people are affected—both positively and negatively—by them; and how people respond to them |

The Annual Research Meeting is a key networking event for the C∙I∙B. Two-day meetings are held in Stellenbosch in early November each year (near the end of the South African academic calendar). All C∙I∙B students, Core Team members, Associates and partner organisations are invited (attendance is compulsory for all C∙I∙B-funded affiliates). This is the one time every year when all these groups meet face-to-face, allowing for networking within and between groups. All C∙I∙B students (50–60 annually) present their work in formats that have varied over the years. In this way, ongoing projects are demonstrated to all groups, and cross-fertilisation of ideas occurs across disciplines and from academics to practitioners and managers. Students are exposed to prospective supervisors and employers, providing career opportunities (see Sect. 30.3.2). Prizes, judged by an international panel of invasion scientists, are given for the best presentations by MSc and PhD students. These cash awards allow students to participate in an international meeting or to visit an overseas laboratory, further facilitating the networking potential of promising young researchers. Annual Research Meetings are usually preceded by a themed workshop hosted by the C∙I∙B.

Themed workshops, held at irregular intervals, have drawn participants from around the world to address an emerging key theme in invasion science that is relevant, not only to South Africa, but internationally. They are hosted by Core Team members, and have made important contributions to invasion science (Table 30.3). Working together intensely on a topic over two or three days has built lasting relationships between the C∙I∙B and international researchers, both in invasion science and beyond, and has produced key research products. These workshops have become an important entry on the calendar for invasion researchers around the world.

The C·I·B has been a founding partner of several working groups that address issues relating to invasive species in South Africa. These typically comprise a complement of scientists, mandated authorities, and implementation agents, as well as any other stakeholders with significant interests, such as commercial growers of alien plants (Kaplan et al. 2017). An example is the South African Cactus Working Group , whose proposed national strategic framework for the management of Cactaceae in South Africa (Kaplan et al. 2017) serves as a blueprint for the strategic plans that are needed for all major invasive taxa. Other examples are the National Alien Grass Working Group , the CAPE Invasive Alien Animal Working Group, the Flower Valley Conservation Trust Sustainable Harvesting Programme Research Working Group, and The Australian Trees Working Group. These networks have served multiple purposes, including collating data to address key research questions (e.g. Novoa et al. 2015; Visser et al. 2016; Kaplan et al. 2017) and aiding in the transfer of research results to stakeholders (Novoa et al. 2015, 2016, 2018).

30.3.4 Information Brokerage

In the framework for the establishment of DST-NRF Centres of Excellence, the DST and NRF required the Centre to “provide access to a highly developed pool of knowledge, maintaining data bases, promoting knowledge sharing and knowledge transfer”. This KPA is closely aligned with several others, notably research (see Sect. 30.3.1), networking (Sect. 30.3.2), and service provision (Sect. 30.3.5). The fact that the C∙I∙B has actively sought to publish all of its research outputs, maintain a database of outputs and underlying data, and pursue knowledge transfer through diverse forms of networking has contributed to meeting this objective.

Annual reports since 2004 (available at http://academic.sun.ac.za/cib/reports.htm) provide details on information brokerage and knowledge transfer through publications, scientific talks, media interactions, newspaper articles, popular articles, popular talks, the C·I·B web page, and social media platforms. In 2005 the C·I·B collaborated with the University of Sheffield, with funding from the U.K. Darwin Initiative, to launch an outreach programme named “Iimbovane: Exploring Biodiversity and Change” focussing on secondary schools. Iimbovane continues to be the Centre’s flagship outreach programme; it aims to increase environmental literacy and inspire secondary school pupils to choose scientific careers through facilitating field and laboratory work that is embedded in the life science curriculum; the programme focuses on under-resourced schools (Davies et al. 2016). The contribution of Iimbovane as a vehicle for information brokerage on invasive species issues to schools is discussed in Chap. 25 (Byrne et al. 2020).

An ongoing component of information brokerage is the C·I·B ‘nugget’ series. These are short summaries of important research papers that can be readily understood by the media and the lay public. As of May 2019, the C·I·B had published 396 nuggets on the website; an archive of these nuggets is available at http://academic.sun.ac.za/cib/news.asp. These nuggets, which form the basis for press releases and stories in the popular media, are also provided to funders who use them in promoting the Centres of Excellence programme.

The C∙I∙B is required to curate, store and make available to users all the information generated by the Centre. The Centre’s Information Retrieval and Submission System (RSS) is an online database that stores metadata and data associated with C∙I∙B projects, including long- and short-term research projects by team members, post-docs and students. The metadata portion of the IRSS is freely accessible via the web page, and permission can be requested to view data files.

30.3.5 Service Provision

In the framework for the establishment of DST-NRF Centres of Excellence, the DST and NRF required the Centre “to provide and analyse strategic information for policy development, as well as other services including informed and reliable advice to government, business and civil society”. The activities undertaken to comply with this requirement are summarised below.

The C∙I∙B incorporated key research findings from its own programmes and from the international literature into the formulation of the regulations under the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEM:BA ) relating to alien and invasive species (Box 1.1 in van Wilgen et al. 2020a, Chap. 1). Most core team members have participated in various task teams assembled by the DEFF to develop objective, science-based lists of alien and invasive species, to compile a risk-assessment framework based on the international best practice and advances in invasion biology in South Africa, and to participate in the drafting of the NEM:BA regulations from 2006 onwards. Revision of the regulations and invasive alien species lists is ongoing, so this is envisaged to be a long-term involvement. The outcomes of diverse C∙I∙B research projects have been used in the process, and expert insights have ensured that the regulations were grounded in international best practice from the fields of invasion biology and environmental management.

Between 2012 and 2014, the C·I·B co-led, with the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research , the development of a National Strategy for Dealing with Biological Invasions in South Africa. This comprehensive strategy, based on the inputs of 19 authors (more than half of them affiliated with the C∙I∙B) and numerous workshop participants, addressed all aspects of the management of biological invasions, covering all taxa and all stages of invasion. Although the strategy was delivered to the former Department of Environmental Affairs (now DEFF) in 2014, it is yet to be formally adopted.

The C∙I∙B was also contracted by the DEFF to review international best practice in the field of risk assessment for invasive species, and to prepare guidelines for the implementation of risk assessment methods as part of national protocols for preventing the introduction of new invasive species. Work conducted at the C∙I∙B to improve risk assessment protocols for invasive species management in South Africa is summarised in Chap. 20 (Kumschick et al. 2020).

In 2008, the C∙I∙B was involved in the development of the “Invasive Species Programme” (now the Biological Invasions Directorate) of SANBI (Wilson et al. 2013). One of the main aims of this initiative was to focus on incursion response (stage 2 in Fig. 30.1). The programme therefore aims to (1) detect and document new invasions; (2) provide reliable and transparent post-border risk assessments ; and (3) provide the cross-institutional coordination needed to successfully implement national eradication plans. This initiative was a departure from historical practice in South Africa, where the introduction of alien species was only considered insofar as it would affect agricultural productivity and human health, and where the impacts of alien species on the broader environment were only considered reactively. The C∙I∙B has been the primary research partner for this SANBI Directorate, and has assisted it in meeting its mandate of reporting on the state of invasion nationally, managing data on biological invasions, and co-ordinating risk assessments .

The Working for Water programme has since 2008 provided funding to the C∙I∙B for research and capacity-building in four broad areas, namely monitoring and evaluation, ecosystem rehabilitation, the reduction of invasions, and resource economics. The C∙I∙B has been most active in the field of ecosystem restoration; such work has included basic research (e.g. Hall et al. 2016; Nsikani et al. 2017; Krupek et al. 2016) as well as ecosystem-level assessments of rehabilitation success (e.g. Fill et al. 2017). In the field of economics, the Centre has investigated returns on investment from biological control (De Lange and van Wilgen 2010) as well as the costs and benefits of achieving effective control of invading plants (Wise et al. 2012; van Wilgen et al. 2016). C∙I∙B researchers have also developed a set of indicators to support the monitoring of the status of biological invasions at a national level (Wilson et al. 2018).

Much of the service provision for government has been done at low or no added cost to government, since the C∙I∙B regards this as part of its funded mandate. The C∙I∙B has explicitly not sought to operate as a consultancy, although individual Core Team members may undertake consultancy work if this is allowed by their employer institutions.

Research involving the City of Cape Town and C·I·B collaborators has addressed diverse issues pertaining to the management of invasive species in urban environments, initially focussing mainly on issues in Cape Town and Ethekweni (Durban ). Examples include the development of a framework for selecting appropriate goals for the management of invasive species in urban settings (Gaertner et al. 2016, 2017; Potgieter et al. 2018); a multi-criterion approach for prioritising areas for active restoration following invasive plant control in urban areas (Mostert et al. 2018); an assessment of the perceptions of people regarding the impacts of invasive species in cities (Potgieter et al. 2020, Chap. 11); and the development of guidelines to enable South African municipalities to become compliant with national legislation on biological invasions (Irlich et al. 2017).

30.4 Conclusions

Over its 15-year history, the C·I·B has added greatly to the knowledge base on all aspects of biological invasions and invasion science in South Africa and globally. It has also facilitated the training of about 200 post-graduate students, many of whom now occupy positions where their knowledge is contributing to management of invasive species in South Africa. There has been substantial transfer of research outputs to influence management (see also Foxcroft et al. 2020, Chap. 28). Focussing on all five key performance areas described above has meant that the C·I·B has done “invasion science for society” in the South African context (van Wilgen et al. 2014; Duvenage 2007). It is, however, impossible to evaluate exactly how much better, if at all, “the C·I·B model” has been in channelling invasion science in South Africa than would have been the case if a different model had been followed. We lack the counterfactual—where would we have been without the C·I·B?

We contend that the South African invasion science fraternity would have been markedly worse off if the C·I·B had not been established and if it had not been mandated to work in all five key performance areas. Although we cannot re-run the 2004–2018 experiment, we feel confident in discussing aspects of the work that would likely not have been addressed had history not unfolded as discussed in this chapter.

In research, the C·I·B was mandated to strive for excellence, and this has led to pioneering work in the field of invasion science such that the C·I·B is a leader in this field globally. This is shown quantitatively by the numbers of peer-reviewed publications and their impact as measured by citations. More generally, the C·I·B is held in high regard by members of the invasion science community around the world, whose members have repeatedly shown willingness to collaborate with the Centre as Fellows and Associates and to employ its alumni, so aiding with the building of substantial networks. Striving for excellence in research, and facilitated through the C·I·B networks, has also led to the production of many syntheses (including this book) which would probably not have happened without the C·I·B. The requirement of service provision pushed the C·I·B to forge stronger networks, and close (even embedded) collaboration with our partners, with products that lead the world; it led, for example, to the world’s first National Status Report on Biological Invasions (van Wilgen and Wilson 2018) and the first framework of indicators for monitoring biological invasions at a national level (Wilson et al. 2018). The same “service provision” KPA also led the C·I·B to develop globally relevant approaches for tackling problems associated with invasions through innovative participation with a diverse range of stakeholders, and to publish these exemplars of what can be done (e.g. Novoa et al. 2018). The “education and training” KPA has produced impressive numbers of graduates, but perhaps it is the work that continues with alumni that demonstrates how well the Centre has trained and maintains contact with its members. The KPA in information brokerage led directly to the Iimbovane outreach programme, facilitating science learning, and emphasising the importance of invasion biology.

Despite our assertions above, we recognise that there are areas in which the C·I·B could have done better. We cannot demonstrate that the C·I·B has achieved its Vision of improved quality of life for all South Africans, nor could it realistically have been expected to do so. It could also not be demonstrated that the C·I·B has helped to reduce the rate of biological invasions through its work with legislative and implementing bodies (e.g. DEFF, SANParks ), as rates of invasion continue to increase (van Wilgen and Wilson 2018). The nature of biological invasions (long time lags and a growing invasion debt ; Rouget et al. 2016) means that we cannot produce a list of species that have been stopped from having impacts in the country, or a ledger of resources saved directly as a result of C·I·B outputs. The Centre’s work in outreach has yet to reach the point where the broad South African public is familiar with invasive species to the extent that they fully support expensive management options (Byrne et al. 2020, Chap. 25). Conflicts of interest that thwart management efforts for many invasive taxa are partly due to the lack of understanding of aspects of invasion science in some sectors of society. While it may not be the role of a Centre of Excellence to reach all South Africans, the C·I·B has failed to make the case sufficiently clearly to the South African government of the need to do this. The impact of the C·I·B’s research, capacity building , networking and information brokerage notwithstanding, the gap between knowing and doing in most areas of invasive species management remains worryingly large (Esler et al. 2010; Shaw et al. 2010; Ntshotsho et al. 2015; Foxcroft et al. 2020, Chap. 28). Biological invasions bring challenges not only to scientific inquiry, but also to socio-economic realms of the social sciences where, although the C·I·B has made inroads, much work remains before a major impact can be claimed. A challenge is to develop and implement more effective ways of working with stakeholders to co-produce knowledge, taking account of the fundamental roles of communication, translation and mediation processes between researchers and practitioners in the context of invasion science in South Africa (Abrahams et al. 2019).

Given the escalating problems with biological invasions globally, and especially in developing countries which lack the resources to apply state-of-the-art interventions at all stages of the introduction-naturalisation-invasion continuum , there is clearly a need for a permanent body such as C·I·B to co-ordinate cutting-edge invasion science in South Africa. The South African Centres of Excellence model has served well as a launch pad for such a body. New ways of supporting and sustaining a centre such as the C·I·B into the future must be sought to serve the changing needs of South Africa. There are also opportunities to roll out the C·I·B model to other regions, most obviously to develop invasion science throughout Africa, but also more widely, for example to other countries within the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) consortium (Measey et al. 2019).

We acknowledge Steven L. Chown, founding director of the C·I·B, whose energy, insights and inspirational leadership were crucial for the establishment of the Centre and for its functioning between 2004 and 2012. Four of the authors of this chapter (SJD, JM, DMR, BWvW) are Core Team Members at the C·I·B. We therefore cannot claim to be unbiased in our assessment of the Centre’s achievements. We thank Jane Carruthers, Robin Drennan, John Hargrove, Brian Huntley, Angus Paterson, Paul Skelton and Laura Meyerson for discussions, comments and suggestions during the writing of this chapter. The C·I·B’s Steering Committee, the Department of Science and Innovation, the National Research Foundation , Stellenbosch University, and all other partners of the C·I·B between 2004 and 2019 are thanked for their many contributions.

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.