Evidence for the readership of early modern prose fiction—and, indeed, for a taxonomy of the genre—is often to be found in the links between books that are articulated by commentators of the period. As a romance blessed with an extended longevity in England thanks to its multilinguality (being read first in French from the 1540s, then in English from the 1590s), Amadis de Gaule features in many such rhetorical alliances and is frequently paired with Sidney’s Arcadia in particular. Such judgements on romance readership manifest their own generic characteristics: they are often negative and are just as likely to be heavily gendered. This is certainly true of the occurrence of Amadis alongside John Barclay’s Latin romance Argenis (1621) in a prohibition emanating from Queen Henrietta Maria’s confessor that stereotypically places the romances in a negative contrast with religious reading:

Besides the Queens confessor and other priests will not endure that she or they should read Barclaies Arginis, Amadis de Gaule, or any such like bookes but only St Katherine’s life, St Brigetts prophecy or other such like holy tales of that stile …1

While this may well refer to the Queen’s actual preferences, it is also potentially another version of the traditional ‘good’ and ‘bad’ books advice that was doled out to both men and women by clerics and humanists throughout the early modern period. It was expressed particularly forcefully in Catholic Spain thanks to the popularity of the libros de caballaría, or books of chivalry, of which Amadis is the most notable example.2 Drawing its roots from the Platonic distrust of fiction, such advice often sought to legislate against the personal effects of reading fiction, such as vicarious emotion and elevated sensuality. Despite the conventional rhetoric of repudiation, the contrastive prohibition as used here is actually an acute piece of genre criticism that implicitly recognizes the many similarities between ‘bad’ fiction (romance) and ‘good’ fiction (hagiography), such as exemplarity, the rhetoric of affect, and the marvellous: the defining difference between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ fictions, of course, lies in the ends to which this material is, or can be, directed.

All three of these elements and others, such as stylized violence and latent or implicit Catholic piety, are certainly found aplenty in both Amadis and Argenis, and they accord with what we know from other contexts about the literary tastes of the Stuart courts and specifically of Henrietta Maria’s circle. Linda Levy Peck’s characterization of the Jacobean court as a world of ‘court scandal and court reform, chivalric nostalgia and classicism, mannerist excess and baroque grandeur’ certainly chimes with the matter and style of Argenis and Amadis, both of which were praised throughout Europe for their rhetorical elegance and courtly sophistication and which certainly manifest plenty of excess and grandeur. Both romances also tapped into, and in the case of the earlier Amadis helped to formulate, the Jacobean celebration of ‘family and uxoriousness’, and like the Stuart houses discussed by Peck, they express the culture’s ‘changing conceptions of the role of the nobility, from magnate to courtier and from courtier to virtuoso’.3 Amadis, for example, is a poet and exemplar of courtly sentiment as well as a marvel of chivalric prowess. Other reasons to link the two works abound: they are both extremely long translated texts that stem from a pan-European fictional tradition rooted in Greek romance (from which the Argenis is derived) and thirteenth-century French prose romance (the origins of Amadis). Both had been or were popular reading matter at the English court. The aristocratic heyday of Amadis in England was during the Elizabethan period, when it was widely read in its French incarnation, but it retained sufficient purchase during James’s reign for Jonson and others to continue to use the name of its heroine, Oriana, for Anna of Denmark, as had been done for Elizabeth in the madrigal tradition.4 Translated in parts by Anthony Munday during the 1590s, the central four-book narrative of Amadis himself (as opposed to his descendants, whose deeds fill out the rest of the cycle) was completed and repackaged in a substantial folio dedicated to Philip Herbert in 1618–19. Barclay’s Argenis, originally published in Latin in 1621, was available in English from 1625. Unlike Munday’s Amadis, it did not have a ‘popular’ readership, but it was nevertheless read late into the seventeenth century and beyond, and indeed initiated the mid-century fashion for lengthy romances of elevated sentiment that also engaged topically with the matter of politics.

In their different ways, Amadis and Argenis are participants in, and indicative of, the internationalism of Jacobean culture and the intensely self-conscious engagement of its fictional prose genres with the precedents of the ancient and medieval pasts as well as the modern novelistic fictions emerging in France and Spain. The earliest fragments of the Spanish Amadís de Gaula date from the fifteenth century, but it was the four-book redaction by Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo (1508) that took Europe by storm during the early modern period, being translated into French, Italian, Dutch, English, German, and Hebrew, and inspiring a frenzy of imitation and continuation that eventually extended the cycle to twenty-four books.5 Crucial to this success was Nicholas de Herberay, who under the patronage of Francis I translated the first eight books into French between 1540 and 1548. Herberay’s Amadis is an act of wholesale cultural as well as linguistic translatio that relocates Montalvo’s intensely peninsular romance (deeply Catholic, embedded in the politics and language of the Reconquest, prophetic, and austere, yet fantastical) into the world of the Valois court. Herberay updated the military elements, swapped peninsular politics for courtly spectacle, expanded the amorous action, and achieved a heightening of the French language that was so elegant, eloquent, and sophisticated that he was praised by du Bellay as ‘l’Homère François’.6 Herberay’s Amadis served as the source text for Anthony Munday’s translations of the first four books of the romance (1590, 1595, 1618–19) and also for the translations of books five, six, and seven that were published in 1598 (reprinted 1664), 1652, and 1694 respectively. The letters and speeches of the romance were so highly regarded that they were extracted and gathered together for the purposes of rhetorical self-instruction in a succession of books calling themselves ‘treasuries’ (Thresors) of Amadis: an English translation by Thomas Paynell of one of these compendia, The Treasurie of Amadis of Fraunce, was published c.1572.

The origins of Barclay’s Argenis are similarly cosmopolitan. Barclay was born in France of Scottish-French parentage, was educated in France, and himself married a Frenchwoman. He spent the years 1606 to 1615 in England at the court of James I where he wrote satirical and political works in Latin and assisted the King in his own literary endeavours. In 1615 he moved to Rome for the sake of his Catholic family, where he composed the Argenis, ‘beyond any doubt the most accomplished novel written in Latin’.7 Argenis was published in Paris in 1621 and Barclay died of a fever in Rome the same year, aged 39.8

Amadis is a neo-Arthurian romance, descended from the thirteenth-century French prose romances of Lancelot and Tristan that were well known, translated, and adapted in the Iberian peninsula. Amadis, the son of Perion and Elisena, is raised outside his family and known as the ‘Gentleman of the Sea’, but his royal parentage is manifested in his remarkable early adventures and deeds of arms. Drawn to the court of Lisuart, King of Great Britain, Amadis falls in love with Lisuart’s daughter Oriana; their love is secretly consummated and a son, Esplandian, is born. But the secrecy of their liaison renders it vulnerable to misunderstanding and jealousy: troubled by fears of a rival, Queen Briolania, Oriana banishes Amadis, who, under the sobriquet of the ‘Faire Forlorne’, continues his chivalric adventures. Meanwhile, Lisuart, his family, and his kingdom are constantly subjected to the machinations of the enchanter Archalaus, which include orchestrating insurrection in Britain and abducting Lisuart and Oriana. A more worldly threat to the lovers arises from Lisuart’s errors of kingship, such as his attempt to secure the marriage of Oriana to Patin, Emperor of Rome. The intervention of Amadis and his allied knights and the rescue of Oriana to the ‘Firme Island’ ruled by him, sets up an alternative locus of power that threatens the stability of Lisuart’s kingdom yet further. Ultimately, however, Lisuart comes to recognize his dependence on Amadis, and both political and familial harmony are restored by the revelation of Esplandian’s identity.

Montalvo’s Amadis is rightly viewed as a bridge between the medieval and the Renaissance, ‘a work of medieval inspiration, composition and themes’ that through the intervention of Montalvo—most notably in his updating and refining of the romance’s language and its treatment of arms and love, a process continued further by Herberay—became the pattern for the genre of the libros de caballería that dominated European fictional prose during the sixteenth century.9 As far as developments in early modern prose are concerned, Amadis refashions for the modern age the technique of interlaced narrative and the ‘cyclic imagination’ of medieval prose romances.10 It is typical of cyclic narrative in having no beginning, middle, or end; it interweaves the narratives of subordinate characters and descendants (such as Amadis’s brother Galaor and his son Esplandian) into the narrative of the hero (some of these narratives, such as that of Esplandian, become separate ‘branches’ emanating from this ‘trunk’); and it employs digressions. Following Horace, discussions of cyclic narrative often debate its capacity for internal coherence and its strategies for managing its inherent diffuseness. A strict control of chronology is important here (chronology being the primary means of structuring a cyclic narrative), as are, paradoxically, the digressions: as well as contributing to the diffuse character of the cyclic romance, they bestow coherence upon its sens (meaning) by showing how the narratives of its diverse matière (substance) ‘harmonize or clash’.11 Chronology is indeed the determining feature of the narrative in Amadis: it has a beginning of sorts, in the story of the encounter between his parents that leads to the hero’s birth, but the four-book ‘trunk’ of the narrative does not end: after the reconciliation of Amadis and Lisuart, adventures continue to proliferate into the next generation, often reprising established ‘memes’ such as the abduction of Lisuart, an event which recurs in the final chapters and triggers the branching out of the Esplandian narrative.12 Having said that, Montalvo is successful in imparting a high level of coherence to his Amadis. This is achieved primarily through the unifying effects of the love narrative and the extension of this amorous theme into the realm of politics by means of the fact that Amadis’s devotion to Oriana and his lordship of the Firme Island set up an alternative power base in the romance that makes amorous loyalty the scenario for knightly disobedience. Lisuart is not a tyrant, but he is prone to kingly folly: during the episode of Barsinan’s rebellion he fails to discern bad advice and acts rashly.13 The (only partially successful) re-education of Lisuart in the art of good government and Amadis’s own entry to the ‘higher felicities’ of rule (961) establish a thematics of kingship that unifies the narrative and (like Barclay’s Argenis) sets up many typically Renaissance similarities between the prose romance and the mirror for policy. As Robert Cummings notes concerning English translations of the latter in this period, there is a tendency to ‘leave behind the empirical and the historical to propose models and offer critiques for princes and states’.14 The modelling and critiquing of statehood certainly underpins Amadis, which in its Spanish incarnation addresses itself directly to the personalities and peninsular politics of Ferdinand and Isabella, the Reyes Católicos. In his preface (not found in either French or English translations) Montalvo praises the ‘santa conquista’ (holy conquest) of Granada using the terminology of his own romance, invoking the dangerous combats, grand speeches, and great praise accruing to the King from his deeds.15 Although the intense geopolitical ambitions of Reconquest Spain are displaced by the Valois obsession with courtly government and cultural supremacy in Herberay’s version, the essential function of Amadis as a critique of princeliness, action, loyalty, and obedience (virtues that map conveniently onto both the amorous and political worlds) nonetheless remains intact.16

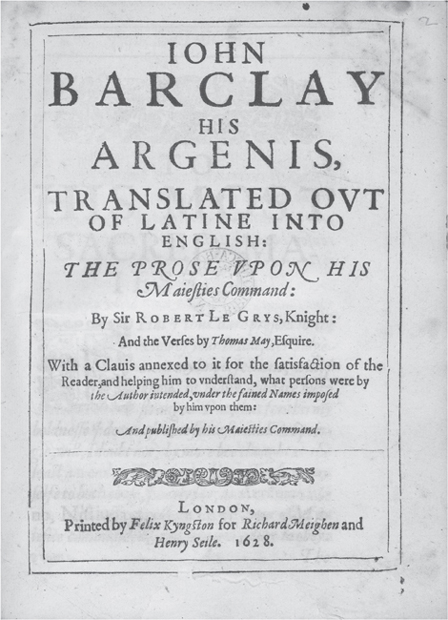

Barclay’s Argenis is even more overtly engaged with questions of statehood and kingship. It was published in Latin in 1621; over thirty Latin editions have been identified and it was translated into all the major European vernaculars.17 English translations were made by Kingsmill Long (1625), with verses by Thomas May and by Robert Le Grys (1628), using the same verses by May. These verses are themselves notable for being May’s first published foray into the translation of politically resonant Latin texts. His translation of Lucan’s Pharsalia (of which the first three books were published in 1626 and the whole in 1627) has earned him a significant place in the narrative of English republicanism. The Pharsalia, like Argenis, is deeply critical of courtly corruption, but unlike Barclay’s romance, it extends that scepticism into a questioning of absolute royal power. Pharsalia and Argenis are linked by their shared interest in the limitations of monarchical absolutism, the element of the subject that was of most topical interest in England. May’s choice of dedicatees for the Pharsalia signals ‘a gesture of support for an anti-absolutist alliance’, but its position is not ultimately a republican one, May preferring instead to close with ‘a generalized appeal to monarchical nationalism’; it is not, then, surprising to find him engaging with the decidedly un-republican Argenis in the same period.18 Argenis is rooted in the societies and discourses of early modern monarchy. The version by Le Grys declares itself on the title page (Figure 4.1) to be ‘translated … upon His Majesties Command’ and Le Grys states in his dedication to Charles I that Barclay was ‘long bred under your Royall Father’; although Argenis had ‘a forraine birth, it was first conceived in this your Kingdome’ and is now ‘cherish[ed]’ of the King.19 According to Sir Dudley Carleton, James I commissioned Jonson to translate it; although entered in the Stationers’ Register in 1623, Jonson’s translation of three books of Argenis was lost in the fire that consumed his library that same year, as remembered in the poem ‘An Execration upon Vulcan’.20

Argenis opens amid ‘broyles and civill dissension’ (107) arising from the rebellion of Lycogenes against Meleander, King of Sicily.21 Meleander is a weak king, principled but indecisive, whose inaction means that he is assailed at home by ‘civil dissensions’ arising from a destabilizing concoction of noble conspiracies and the innate tendency to disobedience of the ‘unruly vulgar’ (247). A lack of effective action against his domestic rebels renders Meleander vulnerable on the international stage as well: the Sardinian prince Radirobanes exploits Meleander’s dependence on his military aid in order to mount his own political and sexual assault on Sicily, culminating in the attempted abduction of Meleander’s daughter Argenis. As so often in Jacobean literature, Sicily’s tumults are a reflection of, and themselves pattern, the domestic turmoil of Meleander’s family: his daughter’s attendant Theocrine has turned out to be the disguised prince of France, Poliarchus, whose real identity is known only to Argenis, and whose potential aid to Sicily is thereby squandered by Meleander’s vengeful pursuit. Meleander is a master of political mésalliance who, apart from his ill-advised compact with Radirobanes, seeks an alliance for his daughter with Archombrotus, incognito prince of Mauritania, who turns out to be Argenis’s half-brother.

FIGURE 4.1 John Barclay, Argenis, trans. Robert Le Grys (1628), title page

Like Amadis, Argenis also circulated in a reduced form. In this case, the focus was on the core narrative of the lovers Argenis and Poliarchus, rather than on the utility of the romance as a rhetorical pattern book, as it had been with the Treasurie culled from Amadis. Again, though, the generic paradigm is a French one, that of the abridgement, or ‘epitome’. Judith Man’s An Epitome of the History of Faire Argenis and Polyarchus was published in 1640; it is a translation of the abridgement Histoire de Poliarque et d’Argenis by Nicolas Coëffeteau, bishop of Marseille. Coëffeteau’s motives in making his abridgement are difficult to discern: as Amelia Zurcher has pointed out, the abridgement of Argenis could have been intended either to increase the range of its readership, or to remove the defences of monarchical authority which Coëffeteau (himself a proponent of papal power) opposed.22 Certainly, in the prefatory material to the English version, there is no indication of the political nature of Barclay’s work, as the reading and writing of the epitome is relocated into an entirely female world of paradigmatic heroinism, virtuous aristocracy, and obedient translation. Casting herself as a grateful and diligent subordinate, Man’s dedication to Anne Wentworth, daughter of the Earl of Strafford (in whose household Man was educated), draws a parallel between her patron and Argenis, ‘the Fairest, most Vertuous, and Constant Princesse of Her time’ and hopes that Anne will herself be matched with an equivalent to Poliarchus, ‘the most Compleat Prince of the Earth’ (sigs. A3r and A4v). Thus, the regal biopolitics on which the plot of the original Argenis is founded are themselves ‘epitomized’ into a local form of dynastic romance, the aristocratic marriage.23

Although not a cyclic narrative like Amadis, Barclay’s Argenis still has to manage its multiple narratives, protagonists, and speakers very carefully. The beginning in medias res pays tribute to the foundational influence of Heliodorus’s Aethiopica, but at the same time it brings together in friendship the men who will later become competitors for Argenis’s hand (and throne), as Archombrotus aids Poliarchus during the latter’s flight from the vengeful pursuit of Meleander. The cause of this strife lies in Poliarchus’s abuse of the laws of hospitality and his potential treason in having disguised himself as a woman, thereby gaining access to Argenis. This explanation remains hidden, however, until it is revealed maliciously in flashback to the third suitor, Radirobanes, by Argenis’s waiting woman, Selenissa, in Book III. Both romances use the techniques of prospection and retrospection, but chronology is disrupted like this more frequently in Argenis than in Amadis, via the use not only of flashback, but also of explanation. For example, Poliarchus’s account for Archombrotus of the origins of the rebellion gathers up into a coherent political narrative otherwise disconnected events spread over a considerable period of time (I.2). Information is also presented incrementally: Poliarchus’s identity as a great man is trailed long before his history is revealed and the minutiae of Lycogenes’s plots emerge over several chapters; such incremental narrative progress and the gradual elucidation of meaning to events is a descendant of the riddling withholding of information (usually a name) that is seen frequently in medieval prose romances such as those from which Amadis is descended.

Barclay maintains an impressive command over the intersecting narratives and conventions that make up Argenis; while drawing freely and unselfconsciously on his stock of inherited narrative motifs, he is also careful to habilitate them to the needs of his own story. Arsidas’s capture by Gobryas’s fleet (a version of the capture by pirates found in Greek romance) turns out to be a highly effective means of infilling the story of Poliarchus’s earlier life, as the enforced cessation of Arsidas’s active narrative thread—his search for Poliarchus—enables him to ‘find’ Poliarchus in a more abstract sense, by learning of his past deeds and royal identity from Gobryas’s inset narration (IV.8–14). The trickster-servant motif is given new life, too, in the theft of Arsidas’s precious cargo, a letter from Argenis to Poliarchus. This serves as an excellent means of getting Argenis’s letter into Poliarchus’s hands and thus accelerating the progress of the plot whilst providing some incidental comedy as Arsidas and Poliarchus talk at cross-purposes thanks to the confusion the thief has introduced in an effort to exculpate himself (V.6–8).

The narratives of Amadis and Argenis are also punctuated by incursions from other genres. Both romances include examples of prose genres such as the letter, the oration, and the prayer, and as discussed below, both stage debates on kingship through dialogue and scenes of counsel. Soliloquies are frequently deployed in Amadis, interrupting and yet amplifying the plot in the same way as does a letter or oration: they proliferate in the emotionally intense section of Book II that deals with Oriana’s jealousy and Amadis’s exile. The soliloquy on Fortune in II.4 is a set piece lament that elaborates cosmic woe out of individual misfortune, as repeated references to the self (‘I’, ‘me’, ‘my’) rub shoulders with proverbial sentiments castigating Fortune for ‘flatteries and wanton intisements’ and warning of the ‘labyrinth of all desolation’ that awaits those who trust in her (326).

Inset verses perform much the same function of elaboration and commentary. In Amadis, the poetry is exclusively amorous, but in Argenis it embraces public genres and is frequently occasional. There is pastoral (99–100), protest poetry (88–9), lament (114–15), epithalamium (335–6), and epic (328–32), for example. Verses can also serve a narrative function: in one particularly self-aware moment in Amadis, an inset verse becomes entangled in the plot, as Amadis and his squire Gandalin overhear the song of praise to Oriana uttered by his soon-to-be-rival, Patin. Full of despair, Amadis has to be nagged and shamed by Gandalin into rebuking this poetic ‘presumption’: doing so, however, places him back on the path to emotional and chivalric recuperation (329).

In Argenis II.2, the poet and courtly commentator Nicopompus (a figuring forth of Barclay himself) describes his intention to write ‘some stately Fable, in manner of a History’ in which he will ‘fold up strange events; and mingle together Armes, Marriages, Bloodshed, Mirth’ that will delight and then ‘with the shew of danger’ ‘stirre up pitty, feare, and horrour’. Some readers will meet with themselves in the fiction, but in a concealed form and mingled with ‘imaginary names’ to resist over zealous glossing. Located somewhere between factuality and fiction, Nicopompus’s ‘new kind of writing’ (a thinly veiled description of Argenis) defies both (109).

When Argenis first began to command some degree of critical attention in the later twentieth century, studies were dominated by its identification as a roman à clef. In an influential reading that located Argenis within the ‘royal romance’ of Stuart (specifically Caroline) self-presentation, Annabel Patterson asserted that the Latin Argenis was ‘quickly recognized as an encoded and fictionalized account of European history’: Queen Hyanisbe ‘represents’ Elizabeth I, Meleander is Henri III of France, and Argenis herself is ‘an allegorical concept, the crown of France’. Paul Salzman’s overview of early prose fiction adopts a similar line: it is ‘a political allegory depicting the religious and political turmoil in France under Henry III and Henry IV’.24 Both Patterson and Salzman take their cue from the tradition of providing a clavis, or key, to Argenis that identifies the historical personages who can be linked to Barclay’s fictional creations. The clavis appeared in the Latin edition of 1627 and was translated for the 1636 second edition of Long’s translation; a shorter version was included in Robert Le Grys’s translation of 1628. It is important to note that in both of its English incarnations the clavis prioritizes the act of reading over that of writing: it advertises itself as a satisfaction to readerly curiosity, an ‘unlock[ing]’ of ‘the intentions of the Author’: it is a scratch to a hermeneutic itch.25 The 1636 Long edition also included the elegant illustrations by Mellan and Gaultier first used in the French edition of 1623: in this edition, clavis and illustrations work together paratextually to enforce a particular kind of reception that is cognizant of the purposeful dignity and continental aesthetics attributed to Barclay’s romance. The self-description in the 1636 subtitle—‘beautified with pictures together with a key præfixed to unlock the whole story’—indicates that by the 1630s the act of reading Argenis was firmly allied with visual pleasure and the heavily managed hermeneutic satisfactions of a particular kind of elite readerly ‘unlocking’. Encountering the English Argenis in this decade was of necessity a cross-cultural activity, framed and directed paratextually by continental, aristocratic norms of reading that insistently and self-referentially invoked art, history, and politics alongside fiction.

As Danielle Clarke has pointed out, the use of a clavis does not necessarily lead to the successful literary decoding that is being advertised. Rather, ‘it may be that the clavis merely serves to restrict access to the subtext by providing an interpretation that gestures at closure’.26 Even assuming that the identifications proposed in the clavis have some validity (and it should be noted here that Nicompompus’s description expressly resists undue allegorization), they represent only a partial story, one that is notably (perhaps deliberately, as Clarke argues) dismissive of alternative modes of romance reading typically characterized as wanton or pleasurable. While Argenis does undoubtedly contain allusions to contemporaneous European history such as the rise of Calvinism (II.5) and to Jacobean politics (for instance the Overbury scandal [I.6] and tax controversies [IV.18]), these elements do not exert a structural or determining influence on its plot, which functions independently of history and possesses its own internal viability.27 This is manifestly clear in the triangulated relationship of Argenis and her two suitors Poliarchus and Archombrotus. Argenis has no historical identity (she is typically glossed as an anagram of ‘Regina’, with an added ‘s’ to make a Greek-sounding name); the deftly realized hatred of Archombrotus for Poliarchus as Argenis’s preferred suitor (expressed for example in IV.4) is rooted in an intense male sensibility that is literary rather than historical in its origins; and the deus ex machina solution to the problem (Archombrotus turns out to be Argenis’s half-brother) has a double heritage in both Greek and medieval French romance (not to mention Amadis itself).

Over-reliance on the clavis should also be qualified by a recognition that Argenis addresses political matters directly through inset dialogues and digressions, in which policy can be discussed in isolation from the matter of the plot itself (as exemplified by the discussion of forms of government in I.18). Hence, Argenis is not properly allegorical romance in a sustained sense, but a flexible and historically self-aware mode of fiction that references and recasts contemporaneous events, personality types, gossip, and scandal as part of its capacious receptivity. The anti-hero Radirobanes, for instance, exemplifies the dangers to the princely person and the commonweal that are attendant upon solipsism, delusion, misplaced lust, and the treacheries they generate. This function is enhanced, not effaced, by his identification in the clavis as Philip II of Spain, which adds a frisson of recognition and serves as an argumentative proof, an exemplum cut from the real world, to demonstrate the truth of Barclay’s wider moral-philosophical point about the perils of excess as practised by the mighty (in other words, tyranny).

Easy as it is to see the ‘unlocking’ act of the clavis as operating on the narrative by revealing a political (and by implication more true and serious) sous-texte, it should instead be viewed in a horizontal, rather than vertical axis, as ‘unlocking’ the purposeful links between the matter of romance and the incident of history: it makes correspondences, rather than negates the matter of fiction, amplifies significations, rather than reduces them. The writers and translators of the different keys knew this, as revealed in the ways they negotiate around Argenis’s innumerable historical inconsistencies. The 1628 clavis, in discussing Radirobanes, acknowledges that his historical alter-ego did not of course ‘dye upon Poliarchus his sword’ as Radirobanes does (sig. 2K1v) and the 1636 version prefaces its discussion of Radirobanes as Philip II by expressing some doubt ‘whether that may in all things suit to his person’. The problem is finessed by a pragmatic acknowledgement of the fact that ‘all things in this Booke are not to be drawne to an Historicall truth’, as Nicopompus himself had dictated (sig. B1r). That observation is nowhere more true than in the chapters in which Radirobanes becomes separated from his army during the wars against Hyanisbe and her ally Poliarchus in Mauritania. As the aggressor, Radirobanes is fatally in the wrong during this conflict, but Barclay nonetheless manages to inject a moving and individualized sense of his vulnerability, fear, and courage as he seeks to hide amongst the Mauritanian troops and then escapes back to his army by swimming his horse across a lake (IV.19–20). Within two chapters he is dead at the hands of Poliarchus, an outcome that is very nearly regrettable following the insight this episode provides into Radirobanes’s version of the ‘great spirit’ (9) that is both the virtue and the potential undoing of all the rulers in Argenis.

Barclay’s combining of romance fiction with historical particularity and broader political instruction was influenced by the writings of his father William in support of absolute monarchy and against papal power, and also by classical texts that did not observe a strict distinction between the prose of instruction and that of fiction.28 One he must have read with particular assiduity is Xenophon’s Cyropaedia (‘Education of Cyrus’), in which the education and achievements of Cyrus the Great are expounded through a mixture of narrative and politico-philosophical dialogues. Xenophon was highly valued by Spenser and Sidney, Barclay’s predecessors in writing politically inflected romance, because of his skill in ‘feigning’ history and philosophy—that is, turning them into the ‘poetry’ (meaning literature/fable/fiction) that can best teach ‘the sound of virtue’, as Sidney puts it in his Defence of Poetry. In the Defence, Sidney repeatedly cites Xenophon’s ‘feigned Cyrus’ as ‘doctrinable’ (instructive), a demonstration of how poetry is better for directing a prince than ‘philosopher’s counsel’, and an embodiment of ‘each thing to be followed’, a ‘perfect pattern’. These sentiments are echoed in Spenser’s letter to Ralegh, appended to the 1590 Faerie Queene, in which Xenophon is to be preferred to Plato because in Cyrus he ‘fashioned a government such as might best be’.29 Xenophon’s feigned history bears fruitful comparison with Barclay’s techniques: his Cyrus is only loosely based on the Cyrus of history, and historical geography and politics have been adjusted to suit Xenophon’s own ‘doctrinable’ ends (for example, Persia is geographically more like Sparta and its politics is actually closer to that of the Greek polis).30 The Cyropaedia was read as a combination of travelogue and mirror for policy throughout the sixteenth century: according to William Barker, whose translation was published in 1552, it offers ‘preceptes’ that instruct in good government, virtue, and policy.31 Exactly the same vocabulary of political example and principle is used in the 1636 clavis to Argenis, which is just as concerned to identify the political direction of Barclay’s ‘counsailes and precepts’ (sig. A6v) as it is to name names: unfortunately, the perpetuation in the English clavis of this mid-Tudor language of political engagement has been obscured by the tendency to read Argenis retrospectively from the allegorical high ground of 1650s romance, rather than as the inheritor of a classical and Tudor discourse of governmental precept that was shared across poetical and political texts. Barclay was certainly not the only writer contemplating the ancient and modern ‘feigning’ of history for the purposes of political instruction at this time: Philemon Holland, translator of Livy, Pliny, and Plutarch, completed his first draft of the Cyropaedia in 1621 as well, although it was not published until 1632.32

The most obviously ‘doctrinable’ element of Argenis is the insight it provides into good and bad government by kings, whether of their own ‘great spirit’, of their nobles, or of the commonweal. Meleander is the indicative negative example: he is certainly ‘doctrinable’ in his deficiencies, but at the same time Barclay’s great skill in articulating the psychology of kingship renders him far more than an exemplary failure. Early on Meleander is tellingly described as ‘perplexed’ by faithlessness (6): the primary meaning here is the political one (‘perplexed’ as used of a state meaning ‘troubled’), but it is indicative of Barclay’s method that there should also be a psychological dimension. The perplexities of Sicily that dominate the plot of Argenis are also the perplexities of a king and a father who is repeatedly confounded (another word with both political and psychological resonances) by the machinations of the people around him, whether subjects, allies, enemies, or family. As the narrative unfolds we learn from many different sources about Meleander’s weaknesses: these include an undue interest in pleasures such as hunting, a failure to grasp the realities of courtly self-interest, a lack of decision (in a further overlaying of politics and psychology he is described as troubled by ‘conflict of his thoughts’ [11]), a failure to discern the trustworthy from the deceitful, and an undignified willingness to ‘covenant’ (62) with a subject as shown by his consideration of a pact with the rebel Lycogenes.

Meleander is also, however, a rhetorical participant in his own ‘doctrinable’ function: by granting him the opportunity for self-analysis he can also be used to model that most notoriously difficult of political desiderata, royal self-correction. An important exchange between the King and Cleobulus in III.4 shows Barclay’s dialogic method at its best, interweaving theoretically driven political dialogue with plot-driven conversation. Debating how to mop up the pockets of resistance left over from Lycogenes’s rebellion, Meleander asks Cleobulus to outline his own faults, as ‘a warning, that I fall not into the same lapse’. Ever the courtly pragmatist, Cleobulus evades the pitfall of ‘saucy freedom’ and ‘prepare[s] the king’s mind’ for counsel by blaming ‘his enemies, the times, and the Fates’ before launching into a lengthy rebuke to his ‘clemency’ (158) that addresses both the specifics of Meleander’s dilemma and the wider principles of absolute power dear to Barclay’s heart. Overtly and carefully chary of tyranny, Cleobulus’s advice nonetheless advocates firm measures to quell the ‘restless dispositions’ of a factional nobility (159), such as removing their royally given estates and powers. Sighing and striking his breast in reply (itself a telling demonstration of the way in which the gestural languages of amorous and political emotion overlay one another in Argenis), Meleander resists the daily ‘rigour’ in government that is implied, by personalizing Cleobulus’s theory: ‘Shall I make All, my enemies, by my strictnesse? Or shall I live like a beast in the Desart? Or rather, furnish my Court with new men?’ (161). The personal frustrations of kingship are clearly audible here alongside the political theorizing.

The use of romance to exert political traction such as this was by no means the invention or even the preserve of the seventeenth century, however. Amadis is equally concerned with the theorization of kingship, although its analysis is delivered not through philosophical dialogue, but elaborated scenes of royal counsel that are derived from the medieval tradition of the quaestio in which arguments for and against a particular thesis are rehearsed. Two such debates occur at moments of crisis in Lisuart’s kingdom—in the lead up to the rebellion of Barsinan in Book I (I.32) and during the early stages of the hostilities between Lisuart and Amadis’s Knights of the Firme Island in Book III (III.1). The first crisis, in which the threat is an external one emanating from the malevolence of Archalaus the enchanter, is moralized by the narrator as a reminder of the dependence of worldly power upon divine favour: Lisuart’s misfortunes are attributable either to his forgetting ‘the author of his good’ or as a consequence of ‘divine permission’ (219). In the second instance, Lisuart is rendered more overtly culpable because it is his unreasonable hostility to Amadis, sown in his mind by the hypocrites Gandandell and Brocadan in hope of gaining the kingdom, that precipitates war. Gandandell plays on Amadis’s importance to Lisuart’s court in order to plant the fear of treachery and alien influence (Amadis being a prince of Gaule) in the King’s mind. This in turn generates a desire in Lisuart to reassert his authority by refusing to grant the Isle of Mongaza to one of Amadis’s allies. In a process of incremental despotism, Lisuart quarrels with Amadis (II.20), refuses reasonable supplications, and even ignores what ought within the moral framework of the romance to be the overwhelming evidence provided via judicial combat (II.22). His knowing repudiation of advice that even he acknowledges to be ‘verie good’ and his reliance on military might (‘their strength is in no way equall to mine’ [521]) accelerate his decline from good to bad king.

Unlike Argenis (and behind it the Cyropaedia), or, indeed, Sidney’s Arcadia, Amadis does not attribute particular agency to the populace, or construe them as a threat to monarchy. In Amadis, the knightly class is both the origin of instability and the source of a king’s protection: the fact that Lisuart has been captured and therefore removed from the military action (I.36) prior to Barsinan’s assault on London (I.38) very much throws the focus onto the role of King Arban, Lisuart’s relative and ally and a member of his court. It falls to Arban to deliver one of the romance’s typically stirring military orations in opposition to usurpation and tyranny, and in defence of ordained monarchy:

Remember the cause of your fight, not onely to maintaine your good king, but your owne liberty: against a tirant, a traitour, and what worse? … Beholde you not the end of his purpose? Which is to ruinate this noble Realme, that hath (by divine providence) beene so long time preserved, and ever-more continued in reputation, flourishing with loyal subjects to their Prince? (260)

The political commentators of Amadis and Argenis are united in their abhorrence of flattery. Here in Amadis the anti-flattery rhetoric invokes Edenic treachery (‘Heard you not the flattering perswasions, which the Rebell used before the assault, thinking to conquer us by his golden tongue?’ [260]). In Argenis the focus is on the practical, deleterious effects of flattery and favouritism upon the courtly polity and the way it undermines monarchical government. The vulnerability of a monarch to being ‘spoil’d with flattery’ (49) is a key weakness in this system, one that Barclay advertises at every turn. In this Argenis is reminiscent of the 1620s satires that excoriated the corrupt counsel, sexual immorality, and profligacy that stemmed from favouritism.33 In both romance and satire, flattery is dangerous because it traduces good government and imperils the legitimacy of monarchical rule, leading to dangerous political speculations. During the inset debate on forms of government in I.18, for example, Anaximander expresses his preference for government ‘in which the people or the Nobles governe: for why should all things depend upon one man’s will’, especially if it can be turned so that the people’s money is ‘lavishly powred [poured] upon Favourites’ (49).

Recent work on ancient prose has noted with interest the links between political philosophy and the Greek novel, itself a paradigm of narrative discourse for Barclay.34 Cyrus is described, for example, in the language of a romance marvel, being ‘worthy of wonder’ for bringing so many nations under his rule.35 Such articulation of wonder (astonishment and admiration) is also a very Jacobean enterprise found in travel writing, history, and drama. Argenis and Amadis are replete with wonders, whether of the human or the magical kind. Indeed, the evocation of wonder is in many ways both the downfall and the apotheosis of prose romance in this period, paradoxically laying it open to the charges of extreme fabulation and imaginative ravishment so often directed at Amadis, or alternatively rescuing it from those very accusations of idleness by pointing to a higher plane of human aspiration in politics, art, or architecture. The hybrid identity of Amadis as both medieval and modern, Spanish and French, means that it juggles wonders such as the Endriagus—a monstrous concatenation of medieval horrors (scaly, hairy, red-eyed, smoking, stinking, howling, and winged) who inhabits the Devil’s Island—and Apolidon’s enchanted palace, which is recast by Herberay into an astoundingly modern architectural marvel based on the château de Chambord, the construction of which was begun by Francis I in 1519.36

As well as supplying wonder to the reader in these diverse ways, Amadis also deploys wonder internally as a spur to action and an index of courage. When shipwrecked on the Devil’s Island, for example, Amadis is surprised by the terror of his shipmates, observing that ‘I see nothing yet that should thus amaze ye’ (631); having heard the story of the Endriagus’s origins and deeds he is duly ‘amazed’ (632) and enacts the drama of (in) comprehension that features so often in romance from Chrétien de Troyes onwards, in this instance questioning internally how such a thing could be born and externally how the monster could have been permitted to live so long. The task of explanation is undertaken by Master Elisabet, physician and repository of knowledge in Amadis, and the hero’s amazement thereby serves a useful purpose in terms of narrative diversification by generating an inset tale of archetypal vice that mingles detailed conversational exchanges, moral commentary, and folkloric descriptions of grisly matricidal and patricidal violence. Amadis is duly amazed for a second time (‘you have told me wonders’, 634) and enacts a conceptual leap that amplifies the coming combat into a battle of moral dimensions by stating his intention to revenge wrong and restore Christian religion to the island. Amazement, and the lack thereof, shifts at this point from being the trigger for an interpretative dilemma that generates an inset narrative and moral digression to being an index of heroism. The ‘admirable maner’ of the monster’s dreadful appearance ‘could not daunt our knight a jote’ (unlike his squire Gandalin, who rather pointedly runs to hide): the hero’s not being amazed or admiring thus becomes a marker of spiritual resistance, heroic agency, and exemplary purpose (636).

The sources of admiration in Argenis tend to be more like those found in Heliodorus, typically invoking wonder by some kind of alterity, whether ethnographic (for example religious rites, I.20) or mythological (the discovery of Cyclops’s bones, II.22). One remarkable feature of the romance is its lack of the kinds of amorous wonder that characterize Amadis: there is no Arch of Loyal Lovers to enthrone Argenis and Poliarchus, no consummation scene, nor even a chaste embrace. The lovers rarely encounter one another and their energies are directed far more towards the evasion, deflection, and subversion of Meleander’s patriarchal authority than the traditional love-business of romance. Argenis emerges as a new kind of heroine in this rescription of love as dynastic pragmatism: the very lack of amorous encounters renders her a much more active and strategizing, indeed subversive, agent even than Oriana, who herself rebukes and resists her father (III.18).

Barclay seems remarkably at ease with the idea of the governing mother who overcomes defective or absent husbands and rebellious nobles: both Hyanisbe, Archombrotus’s adoptive mother, and Timandra, Poliarchus’s mother, rule alone and take command of their armies. For much of the romance, it looks as though Argenis is being schooled in the traits of this romance gynocracy, as manifested particularly in her mastery of emotion: she becomes expert in managing ‘the combat of griefe and dissimulation’ such that ‘her words and gestures might fall into a just temper’ (25). Temperance, or emotional balance, is an indispensable attribute for a monarch, but an unusual aspiration for a romance heroine. Also unusual is the way in which Barclay recasts female dissimulation as a form of legitimate resistance to a flawed king: Argenis in her own way is just as much a threat to the stability of Meleander’s throne as are Lycogenes or Radirobanes. She has her own epithet, too—as ‘quicke-witted Argenis’ (187), she is far better than her father at scenting out treachery and casting her own counter-plots. In a splendid speech comparing herself to Iphigenia, Argenis articulates the frustrations of a woman at the heart of political events, yet without political influence. The letter she writes to Poliarchus binding him to revenge upon Radirobanes for his plots against her and outlining her plans for the ‘ghastly spectacle’ of her suicide on her forced wedding day is lucid, dignified, and magisterially ‘violent’, the public-private prose of a princess and an implicit rebuke to the men who command and, so she fears, fail her (IV.5; 256). In its rhetorically charged ‘admirable maner’ it encapsulates one of the many common threads linking Argenis and Amadis, both of which, like Argenis’s letter, are exhortations to the mighty born of an insistent sense of the dangers and opportunities inherent in the exercising of power.

Barclay, John. Argenis, ed. Mark Riley and Dorothy Pritchard Huber, Bibliotheca Latinitatis Novae/Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, 273, 2 vols. (Assen: Royal van Gorcum and Tempe, AZ: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2004).

Munday, Anthony. Amadis de Gaule, ed. Helen Moore (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004).

Patterson, Annabel. Censorship and Interpretation: The Conditions of Writing and Reading in Early Modern England (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1984).

Salzman, Paul. English Prose Fiction, 1558–1700: A Critical History (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1985).

—— Literary Culture in Jacobean England: Reading 1621 (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002).

Zurcher, Amelia A. Seventeenth-Century English Romance: Allegory, Ethics and Politics (New York and Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).