10

Autism:

The Extreme Male Brain

At this point on our journey, we have looked at the evidence for the male brain—slightly lower empathizing skill and slightly better systemizing skill—and for the female brain, which shows the opposite profile. These are normal sex differences. They are small, but real (in the sense of being statistically significant).

But what about individuals who are more extreme? How would those who have a much lower ability to empathize, coupled with an average or even talented ability to systemize, behave?

These are the people (mostly men) who may talk to others only at work, for the purposes of work alone, or talk only to obtain something they need, or to share factual information. They may reply to a question with the relevant facts only, and they may not ask a question in return because they do not naturally consider what others are thinking. These are the people who are unable to see the point of social chit-chat. They do not mind having a discussion (note, not a chat) on a particular issue in order to establish the truth of the matter (mostly, persuading you to agree with their view). But just a casual, superficial chat? Why bother? And what on earth about? How? For these people it is both too hard and pointless. These are the people who, in the first instance, think of solving tasks on their own, by figuring it out for themselves. The object or system in front of them is all that is in their mind, and they do not stop for a moment to consider another person’s knowledge of it. These are the people with the extreme male brain.

Present them with a system and they seek to spot the underlying factual regularities. They tune in to the tiny details to such a great degree that, in their fascination with cracking the system, they may become oblivious to all those around them. The spotlight of attention on one tiny variable becomes all that matters, and they might not notice if a person stood next to them with tears rolling down their cheeks. All that they focus on is determining the unvarying if-then rules, which allow them to control and predict the system.

Present them with some speculation about what someone might think or feel, or with a topic that is ultimately not factual, and they switch off or even avoid it because of its unknowability and therefore unpredictability.

When one hits the edge of the range in this way, I suggest that you are meeting autism. Before we look more carefully at this idea, let me remind you what autism is.

Autism

Autism is diagnosed when a person shows abnormalities in social development and communication, and displays unusually strong obsessional interests, from an early age.1

When I started researching autism in the early 1980s, only a handful of scientists in the UK were actively investigating it. At that time, autism was thought to be the most severe childhood psychiatric condition, and it was thought to occur rarely.

It was thought to be severe because half of the children diagnosed with autism did not speak, and most (75 percent) had below-average intelligence (IQ). Their poor language ability and low IQ predicted greater difficulties. In addition, they had the core features of autism: poor social skills, limited imagination, and obsessive interests in unusual topics, such as collecting types of stones or traveling to every railway station in Britain just to look at each depot.

They did not learn from others in any social way, and their narrow obsessions often stopped them from picking up broad knowledge. Many of them lived in a world of their own, and were described as unreachable, as if “in a bubble.” Others who were socially interested would talk to you without eye contact, or stare at you for too long, or touch you inappropriately, or simply badger you with questions on a topic of their choosing and then walk off without warning. No wonder autism was described as severe.

And autism was thought to be rare because only four children in every 10,000 seemed to be affected in this severe way.2

These children attracted the attention of scientists for several reasons. Their social disorder begged for an explanation, since other children of the same IQ seemed appropriately sociable by comparison. Furthermore, some of them also had “islets of ability”: even though they were unable to communicate appropriately, some were lightning-fast at mathematical calculation, for example. Some could name which day of the week any date (past or present) falls on (so-called “calendrical calculation”). Some could tell you instantly if a number is a prime number and, if it is not, the factors of that number. Some could recite railway timetable information to a precise degree, from memory. Some could acquire vocabularies and grammars in foreign languages at a tremendous pace, even though they were unable to chat in these languages, or even in their native tongue. This is clearly a sign of a different kind of intelligence.3

That was the picture of autism then. Children like these are still real enough, and their problems are still regarded as severe and rare. But an interesting shift occurred during the early 1990s.

It had always been known that a small proportion (25 percent) of children with autism have normal, or even above average, intelligence (IQ), but slowly such high-functioning cases started being identified more frequently. By the late 1990s it seemed that high-functioning children with autism were no longer in the minority. It is part of the diagnosis of autism that such children are late to start talking. By late, I mean no single words by two years old, and no phrase speech by three years old. But in these high-functioning cases of autism, the late start in language does not seem to stop them developing good or even talented levels of ability in mathematics, chess, mechanical knowledge and other factual, scientific, technical, or rule-based subjects.

Asperger Syndrome

In the 1990s clinicians and scientists also started talking about a group of children who were just a small step away from high-functioning autism.

They diagnosed these children as suffering from a condition called Asperger Syndrome (AS), which was proposed as a variant of autism. A child with AS has the same difficulties in social and communication skills and has the same obsessional interests. However, such children not only have normal or high IQ (like those with high-functioning autism) but they also start speaking on time. And their problems are not all that rare.

Today, approximately one in 200 children has one of the autism spectrum conditions, which includes AS, and many of them are in mainstream schools. We now have to radically reconceptualize autism. The number of cases has risen from four in 10,000 in the 1970s, to one in 200 at the start of this millennium. That’s almost a ten-fold increase in prevalence. This is most likely a reflection of better awareness and broader diagnosis, to include AS.

People with AS do not suffer from problems as obviously severe as are seen in the mute or learning-disabled child with autism. But most children with AS are nevertheless often miserable at school because they can’t make friends. It is hard to imagine what this must be like. Most of us just take it for granted that we will fit in well enough to have a mix of friends. But sadly, people with AS are surrounded by acquaintances, or strangers, and often not by friends, as we understand the word. Many of them are teased and bullied because they do not manage to fit in, or have no interest in fitting in. Their lack of social awareness may even result in their not even trying to camouflage their oddities.4

The Autism Spectrum

If you put classic autism, high-functioning autism, and AS side by side, you have what is called the “autism spectrum.” So, who are these individuals? You can already see that there is a spread of abilities. Compared with someone of the same age and IQ level without autism, all people with autism or AS are seen as socially odd, odd in their communication, and unusually obsessional, to varying degrees; however, some people with autism have little or no language, while others are very verbal. Some have additional learning difficulties, while others can be members of MENSA (the association for gifted people of high intelligence). We will meet one such gifted individual in the next chapter.

But first, a few more facts about the autism spectrum. Autism spectrum conditions are strongly genetic in origin. The evidence for this is derived from studies of twins and families. If an identical twin has autism, the chance of his or her co-twin also having an autism spectrum condition is very high (between 60 and 90 percent). If a non-identical twin has an autism spectrum condition, the equivalent risk for his or her co-twin is much less (about 20 percent). Since a key difference between identical and non-identical twins is that the former share 100 percent of their genes, whereas the latter only share on average 50 percent, this strongly suggests that autism is heritable. And family studies suggest that if there is a child with autism in the family, there is a raised likelihood of their sibling also having an autism spectrum condition.

Autism spectrum conditions also appear to affect males far more often than females. In people diagnosed with high-functioning autism or AS, the sex ratio is at least ten males to every female. This too suggests that autism spectrum conditions are heritable. Interestingly, the sex ratio in autism spectrum conditions has not been investigated as much as perhaps it should have been, given that Nature has offered us a big clue about the cause of the condition.5

Autism spectrum conditions are also neurodevelopmental. That is, they start early—probably pre-natally—and affect the development and functioning of the brain. There is evidence of brain dysfunction (such as epilepsy) in a proportion of cases. There is also evidence of structural and functional differences in regions of the brain (such as the amygdala being abnormal in size, and less responsive to emotional cues).6

Autism is an empathy disorder: those with autism have major difficulties in “mindreading” or putting themselves into someone else’s shoes, imagining the world through someone else’s eyes and responding appropriately to someone else’s feelings. In my earlier book, I called autism a condition of “mindblindness.”

People with autism are often the most loyal defenders of someone they perceive to be suffering an injustice. In this way, they are not uncaring, or cold-hearted psychopaths who want to hurt others. On the contrary, when they discover that they have inadvertently hurt another person, perhaps by saying something which has caused offense, they are usually shocked and cannot understand why their actions have had this kind of impact. They typically find it equally puzzling to know how to repair such a hurt. Certainly, they do not set out to upset others. Broadly, they have difficulty making sense of and predicting another’s feelings, thoughts, and behavior.7

Autism is also a condition where unusual talents abound. These children pay acute attention to detail, and can be the first to spot something that no one else has noticed. They make fine discriminations between things that may be unimportant to, or outside the awareness of, the ordinary person, such as noticing the tiny fibers in the blanket on their bed, and developing a preference for that particular blanket, even though to anyone else the blankets on offer all look and feel the same. They love patterned information, or making patterns, and so will spot the similarities in strings of numbers in otherwise disconnected contexts, or the similarities in the veins of leaves, or the sequence of changes in the weather.

Take one child I came across. At the age of five, he asked his school teacher how computers work. She explained to him that computers store information in a binary code so that every bit of information is either present or not. He immediately said, “But that’s how my brain works!” and gave himself the nickname “Binary Boy.”

His mother gave me a real example of this extraordinary type of mind in action. Every day they would walk down their street in Fulham, west London, to school. One day the five-year-old boy said to his mother, “We had better tell the woman who lives at number 105 that her parking permit runs out next Tuesday.” His mother looked at her son, astonished. “How do you know that?” she asked. “Well,” he said, “the parking permit in her windscreen has the date when it runs out. That’s her car, the red Landrover, right there.” It turned out that this five-year-old boy had first worked out which car in the whole street belonged to which house. This by itself was no mean feat, as there were hundreds of houses on each side of the road. He had then noted the expiration date in every windshield of every car in the street. His mother, flabbergasted, decided to test his knowledge.

“So, who does that green Saab belong to?” she asked.

“That would be the old man at number 62,” he replied in a monotone voice. He was right.

“And when does his permit need renewing?” she asked, not quite believing what he was telling her.

“April 24th next year,” he replied, in an equally matter-of-fact tone. She went over and checked. Sure enough, he was correct.

“So are you telling me you know every expiration date of every car’s permit in this street?”

“Yes,” he said, in a slightly bored tone.

“Do you know anything else about these permits?”

“I can tell you the serial number for each permit, too. The green Saab is a Saab 900, and its permit is serial number A473253. The red Land Rover’s permit is serial number Z534221.”

People with autism not only notice such small details and sometimes can retrieve this information in an exact manner, but they also love to predict and control the world. Phenomena that are unpredictable and/or uncontrollable (like people) typically leave them anxious or disinterested, but the more predictable the phenomenon, the more they are attracted to it.

Some children with autism can look at the spinning of a wheel on a toy car, over and over again. Others can watch the spinning of the washing machine, for hours. Yet others become engrossed in the pattern created as raw beans or grains of sand fall through their fingers into a jar, or in strings of numbers such as dates of birth or phone numbers.

When they are required to join the unpredictable social world, they may react by trying to impose predictability and “sameness,” trying to control people through tantrums, or insistence on repetition. The pleasure they get watching a toy train go round and round the same track, something that is exactly controlled depending on the position of the points, is something they may try to recreate in the social world, trying to get people to give the same answers to the same questions, over and over and over again. This should provide us with a strong clue about the nature of their brain type.

Many people with autism are naturally drawn to the most predictable things in our world—such as computers. To you and me, computers go wrong, so they are far from predictable. But unlike people, computers do follow strict laws. If they go wrong, there is a finite number of reasons for this, and if you are patient enough, or understand the system well enough, you will logically track down how to fix the problem.

Computers are a closed system: they are, in theory, knowable, predictable, and controllable. People’s feelings and thoughts and behavior are ultimately unknowable, less predictable and less controllable open systems. Some people with AS will figure out things on the computer at what to an outsider might seem like an intuitive level but which is the product of a very exact mind storing rules and patterns and sequences in an orderly and logical way. Others with AS may not make computers their target of understanding, but may latch on to a different, equally closed system (such as bird-migration or trainspotting).8 A young man with AS who I met had become obsessed with pressure points on the human body, and explained to me that applying pressure to these points with your thumb could kill a person. He had learned (and could demonstrate) the dozens of ways you could kill someone in seconds, using only your thumb as a weapon.

Closed systems can appear superficially very different from each other, but they still share the property of being finite, exact, and predictable. One child might become obsessed with Harry Potter, rereading the books and rewatching the videos hundreds of times, able to describe the facts in astonishing precision when asked. Another child might become obsessed with War Hammer, the miniature model soldiers that can be arranged and rearranged with total control and precision, his collection becoming ever larger and ever closer to completion.

One young man with AS latched on to juggling as the ultimate closed system. He had tuned in to the mathematics of juggling, the rules that determine whether a juggling trick will succeed or fail. He explained to me that the two key factors are the angle at which the ball leaves your hand and the height of the peak before the ball begins its downwards trajectory. These two factors are totally controllable, especially if you spend (as he did) three hours per day juggling. He could juggle with nine balls in the air at a time.

This attraction in becoming an expert at understanding a closed system is particularly apparent in the high-functioning cases of autism or AS. Here we can see the workings of the autistic mind, without the associated problems of language disorder or developmental delay and learning difficulties that frequently accompany classic autism. People with AS have their greatest difficulties on the playground, in friendship, in intimate relationships, and at work. It is here, where the situation is unstructured and unpredictable, and where relationships, social sensitivity, and reciprocity matter, that people with AS struggle.

In sum, one can think of people with autism and AS as people who are driven by a need to control their environment. Being in a relationship with someone with AS is to have a relationship on their terms only. You can play with a child with AS so long as the game is the game they want to play. And as we will see, a relationship with an adult with AS is only possible when the other person is able to accommodate in the extreme to their partner’s needs, wishes, and routines. The more controllable an aspect of the environment is, the more people with autism or AS are driven to comb its every detail, and to master it.

Adults with Asperger Syndrome

I run a clinic in Cambridge for adults who suspect that they may have AS, but whose problems went undetected in their childhood. AS just wasn’t recognized when they were at school. So they have limped through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, and slowly the accumulated difficulties have piled up until they reach a clinic like ours, at which point they are desperate for a way to make sense of a lifetime of not fitting in, of being different.

In most cases these patients also suffer from clinical depression, as they have not found an environment, in terms of a job and a partner, that accepts them as different. They long to be themselves, but instead feel forced to act a role, desperately trying not to cause offense by saying or doing the wrong thing, and yet never knowing when someone else is going to react negatively or judge them as odd.

Many of them struggle to work out a huge set of rules concerning how to behave in each and every situation, and they expend enormous effort in consulting a sort of mental table of how to behave and what to say, from minute to minute. It is as if they are trying to write a manual for social interaction based on if-then rules, or as if they are trying to systemize social behavior when the natural approach to socializing should be via empathizing.

Imagine the sort of Victorian books on social etiquette for dinner parties (which fork to use, how to reply to questions such as “Would you like some more dessert?”, and so on) but writ long, to cover every eventuality in social discourse. Of course, it is impossible to be fully prepared, and while some of these individuals do a brilliant job in getting close to this goal, they find it physically exhausting. By the time they get home from work, where they have been pretending to interact normally with other people, the last thing they want to do is socialize. They just want to close the door on the world, and say the words or perform the actions that they have had to censor all day. They do not know why they are not allowed to say what they think, and they wish that others would just speak their mind. It is difficult for them to understand how speaking one’s mind could cause offense or lead them into social difficulties.9

For example, an employee with AS might say (truthfully) to a prospective client, “Our company produces low quality goods that are unreliable.” Or a young man with AS might say to his female office colleague, “You’ve got big breasts.” Or a man with AS might say to someone at a dinner party, “Your voice is too loud and unpleasant.” Or a child with AS might say to his teacher, “You’re stupid.” All of these statements might be true, but it is just self-evident to us that they should not be said. Such things are far from evident to someone with AS.

You might try to advise someone with AS that on certain matters they should just keep quiet to avoid causing offense to the listener. But their low empathizing often leads them to think that it is not their problem if someone is offended. One man with AS put it very clearly to me:

What I say is what I believe. How someone else perceives what I say is nothing to do with me. If they’re hurt or offended, that’s not my problem. I just say what is true. I just express myself, and where my words land are nothing to do with me. It’s no different to when I use a toilet. Once the feces have left my body, I’m no longer responsible for what happens to them in the toilet, or beyond.

This statement shows that this man (who had an IQ in the superior range) could not appreciate that people are different from toilets and other inanimate objects. He could not see that people have feelings that we have a responsibility not to hurt.

Nevertheless, many people with AS learn to stay silent, rather than make a personal comment about someone. They do this not out of any empathic understanding or concern, but because that way they avoid getting into trouble. Once again, they learn a rule rather than being motivated by empathy.

Another man with AS put it to me very succinctly: “If you don’t feel it, fake it.” He said this when I asked him what he would do if he saw someone else was a bit tearful. He said he had learned to say, “Would you like some tea?” and sound helpful, but the truth of it was that he did not feel any emotion in response to the other person’s tears.

So many adults with AS have to train themselves, through trial and plenty of error, to learn what can be said or done, and what can’t. What an effort.

Below I will outline the typical set of characteristics that we see in adults with AS in our clinic, almost all of whom are male.

As Children

When we look back at the childhoods of people with AS, we find a common picture emerging. They almost always tended to be loners. Even though they were aware of other children in the playground, many of the children with AS did not know how to interact with them. Some of them describe the experience as being like “a Martian in the playground”10 and many of them said that they preferred to talk to adults such as teachers than to the other children.

Sadly, it was the case that as children they were rarely invited to play at other children’s houses or to their birthday parties, and if they were invited once, they tended not to be invited back. When we ask their parents what kind of play their child produced, we discover that they did not produce much varied, social pretend play. Instead, they would be far more focused on constructional play (building things), or reading factual books (such as encyclopedias). If other children did come round to play, the child with AS behaved in a way that was often described as “bossy,” trying to control the other person. Not just choosing the game, but telling the other child what to say and what to do.

Many of them as children were content to spend long, solitary hours playing with jigsaw puzzles, Legos, and other constructional systems. Some also built houses out of boxes around the home, constructed dens outside, became engrossed in miniature systems such as model-making, or played with armies of tiny figures of knights in armor, soldiers, or fantasy figures.

They all spoke on time (this is part of how their diagnosis is made) but some acquired a precociously exact vocabulary. For example, one mother told me that her (now adult) son’s first word was “articulated lorry” (note: not simply “lorry”) just after his first birthday.

Because of their unusual interests and lack of normal sociability, many of these adults with AS reported having been bullied or teased by other children at school. This caused depression in some individuals, while others turned bully themselves through the frustration and anger they felt at the unfair treatment they received from their peers.

Typically they pursued their own intellectual interests to high levels, learning books of facts, or studying the movement of the sun and shadows around their bedroom, or attempting to breed tropical fish, becoming very knowledgeable on these subjects. But many also failed to hand in the required schoolwork, so that they were failing in some academic subjects. Having no drive to please the teacher, they simply followed their own interests rather than the whole curriculum.

Throughout childhood there were signs of an obsessional or deep interest in narrow topics, such as collecting a complete set of wildlife picture cards, or carrying around mathematical equations in their pockets, or learning language after language. They were building up collections of knowledge. As for the female patients with AS, many of them recall being described as “tomboys” in their behavior and interests.

As Teenagers

When we asked our patients with AS to recall their adolescence, most recall that they did best at factual subjects such as math, science, history, and geography, or at learning the vocabulary and syntax of foreign languages.

Many (but not all) were weakest at literature, where the task was to interpret a fictional text or to write pure fiction or to enter into a character’s emotional life. Some learned rules to systemize the analysis of fiction and obtained good grades in this way. In an extreme example, a young woman with AS bought exam-preparation books and learned literary criticisms about texts without actually reading the texts herself.

Many became acutely aware that they were low in social popularity, and they found it difficult to make friends; males with AS found it partic- ularly difficult to establish a girlfriend relationship. Their obsessions continued, and they changed topic only when the last one was fully exhausted—generally every few years. The female patients found their adolescent peer group particularly confusing and impossible to join: “All that giggling in lifts, and talk about fashion and hair. I couldn’t understand why they did it.”

Some got into trouble for pursuing unusual interests (the chemistry of poisons, the construction of explosives). Most of them at one time or another had said things that had hurt others’ feelings, often on a frequent basis, yet they could not understand why the other person took offense if their statement was true. Sometimes the offensive remark was rather blatant: “She’s fat,” or, at a funeral, “This is boring.”

As Adults

Many adults with AS have held a series of jobs, and have experienced social difficulties leading to clashes with colleagues and employers, resulting in their dismissal or resignation. Their work is often considered technically accomplished and thorough, but they may never get promoted because their people skills are so limited.

Some have had a series of short-term sexual relationships. Such relationships usually flounder, in part because their partner feels that they are being over-controlled or used, or because the person with AS is not emotionally supportive or communicative.

Other people recognize that those with AS are socially odd (though this is harder to detect in the female patients), and their few friends are also usually somewhat odd themselves. Typically, their friendships drop away because they do not maintain them.

A significant proportion of adults with AS experience clinical levels of depression and some even feel suicidal because they feel that they are a social failure and do not belong. One woman described her feelings to me very bluntly:

Do I think that AS should be treated as a disability or simply as a difference? Clearly it should be treated as a difference, since then the person is accorded all the dignity and respect they deserve. But do I wish I hadn’t been born with AS? Yes, I hate my AS, and if I could be rid of it I would.

Another man with AS described his life in a very graphic way:

Every day is like climbing Mount Everest in lead boots, covered in molasses. Every step in every part of my life is a struggle.

In adulthood, many of them continue to collect hundreds of one type of object (soccer programs, CDs, and so on). Their books and CD collections are often organized in highly systematic ways, such as by genre, date last played or read, sex of author/composer or date of first publication/recording, and they get very upset if one of these is out of place. And even if the collection is not obviously ordered to the naked eye but instead lies in a messy heap, the person with AS often knows exactly what they have in their collection—it is mentally very ordered.

Their life is often governed by “to-do” lists. They may even make lists of lists. Their domestic lives are frequently full of self-created systems. For example, one man always had five tubes of toothpaste in the bathroom, lined up in an exact way alongside the sink. He explained that when one tube runs out, he brings the next one forward to replace the empty one. When out shopping, he would then buy a replacement, and put it into the new empty position (behind tube number four) so that he was always prepared. Many adults with AS put a huge number of hours into planning every detail of their lives in order to maintain the systems that they live by.

Many of them continue to say things that offend others, even though they do not intend any offense. They may learn to avoid obvious statements like reference to someone’s weight, but instead commit faux pas of a more subtle kind. For example, one man with AS turned to his sister at her second wedding, as she sat at the reception dinner table with her new husband, and asked, “How’s David [the first husband]? Do you see much of him these days?”

Almost invariably, those with AS are disinterested in small talk and do not know how to do it, or what it is for. They frequently feel that they cannot say what they think, as people often seem shocked by their independent, extreme, unempathic, and sometimes offensive views. For example, one man with AS described his politics as “green fascism”: the belief that anyone spoiling nature should be shot. Another said he believed in “meritocratic misogyny”: the belief that women have not achieved equally high positions in society because they are less able. Most have no time for political correctness or spin. They believe in saying what they think, seeing no point in sugaring the pill or spin-doctoring.

Many adults with AS hate crowds, or people dropping in. This is probably because they find it anxiety-inducing or annoying when people do things unpredictably. This might include people moving without warning, or a guest moving an object from its customary place on the mantlepiece to a new position on a different shelf. If people are invited over for supper by their partner, the person with AS might just walk into the next room and read a book while the guests are at the table.

Politically or in other ways, their views are often held very strongly, and are black or white. They are typically convinced by the rightness of their beliefs, and given the chance will spend hours relentlessly trying to convince the other person to change their view. They do not understand how one’s beliefs can be a matter of subjectivity or just one point of view. Rather, they believe that their own beliefs are a true reflection of the world and, as such, that they are correct.

If you sit next to someone with AS at dinner you can begin to feel like you are being pinned to the wall as they will often go too far when explaining their views. In response to a polite question about their weekend, the person with AS might go into too much detail about the technicalities of their hobby, not realizing that their listener has long since become bored. Other individuals with AS might converse too briefly and provide only factual responses. It is as if they are unable to judge what another person would like to hear or find interesting.

Their lives are also often governed by routines: going to the same places every weekend or every holiday, eating in the same restaurant, having the same after-work routine each evening. It is often commented that people with AS notice small details that others miss.

Most would not bother to read a novel of pure fiction or watch a human drama on television unless it was based on historical fact, science (science fiction), or an issue (politics). Instead they read factual books or watch documentaries. In this way, their beliefs are in fact like information databases, storing up facts. They frequently describe their brains as being just like computers—either containing some piece of information or not. In other words, they think in a way that is binary, digital, and precise; they do not think in approximations in the same way that many other people do. In a recent book about an artist with AS, Sally Wheelwright and I coined a phrase for this: “the exact mind.”11

Some become obsessed by signs as patterns to causes. For example, some adults with AS are fascinated by crime reports because they enjoy working out basic rules of the following kind: if the victim showed physical signs a, b, and c, then the murder in all likelihood involved techniques x, y, and z. Others become obsessed with natural or man-made disasters such as hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, floods, and bomb attacks, focusing on the physical event rather than the plight of the victim. Some people with AS call this approach to the world “forensic,” beautifully epitomized by Sherlock Holmes, and they extend this approach to understanding social situations.

One patient I met watched news reports of buildings collapsing after terrorist bombings, over and over again, in order to understand the differences between types of architecture and the consequences an attack would have for these. He could give me statistics on how many people were killed in each building collapse and the materials that the building was made from, as well as an account of the physics of each type of material; however, he admitted that he did not find himself spontaneously stopping to think about the victims or their families.

People with AS will often also admit they would not know how to comfort someone. They would not notice that someone was upset unless the person told them so, or was showing extreme outward signs of distress, such as tears.

Some of them also end up in trouble with the law, not for acts of dishonesty but for aggression when they don’t get their own way. Some become obsessed with role-play games that are tightly scripted and rule-based, such as Dungeons and Dragons.

Some marry, but remain married only if their partner is patient to the point of saintliness, is able to accommodate family life to the rigidity of the autistic routines and systems, and can accept an eccentric, remote, often controlling partner. Some marry a partner of a different ethnicity, possibly because their social oddness and communication abnormality is less apparent to a non-native speaker. Often their partners learn to avoid asking friends around because their spouse with AS is so socially embarrassing. Their social life may be restricted to that which is structured for them (for example, through the church) or by others.12

I should stress that the above social difficulties are typical only of those people with AS who are suffering enough that they have sought the help of a clinic. Against this catalog of social difficulties, we must keep in mind that AS involves a different kind of intelligence. The strong drive to systemize means that the person with AS becomes a specialist in something, or even in everything they delve into. One man with AS in Denmark who I met put it this way: “You people [without AS] are generalists, content to know a little bit about a lot of subjects. We people [with AS] are specialists. Once we start to explore a subject, we do not leave it until we have gathered as much information as we can.” In effect, the systemizing drive in AS is often a drive to identify the underlying structure in the world.

Now that you have a picture of autism and AS, it is time to relate this to the idea of the extreme male brain.

The Extreme Male Brain Theory of Autism

The extreme male brain (EMB) theory of autism was first informally suggested by Hans Asperger. Here is what he said:

The autistic personality is an extreme variant of male intelligence. Even within the normal variation, we find typical sex differences in intelligence . . . In the autistic individual, the male pattern is exaggerated to the extreme.13

Asperger wrote this statement in 1944, in German. The above is Uta Frith’s translation, which did not reach the English-speaking world until 1991. His monumental idea therefore went unnoticed for almost fifty years, and it took until 1997 for anyone to set out to see if there was any truth to his controversial hypothesis.14

What did Asperger mean by an extreme of male intelligence? Psychologists usually define intelligence very narrowly as performance on IQ tests. Asperger left this term undefined, but he probably meant it in the widest sense, that there are sex differences in personality, skills, and behavior. In order to make any progress in this area a half-century later, a tight definition of the male and female brain is required so that we can test the EMB theory empirically.

A model of the male and female brain, and their extremes

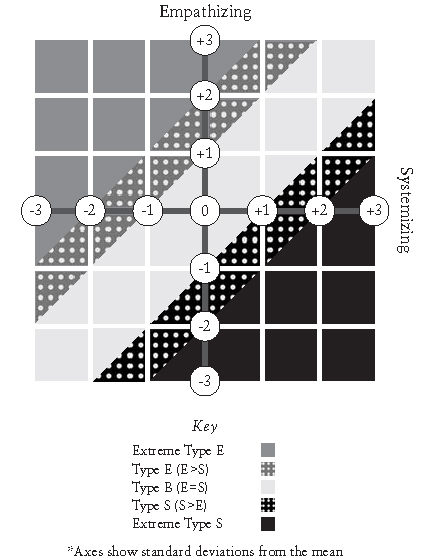

fig 8.

Throughout this book I have defined the female brain as being characterized by the individual’s greater ability to empathize than systemize (E>S). If you look at Figure 8, those with the female brain are the grey, dotted zone. The male brain is defined as the opposite of this (S>E). They are the black, dotted zone.

You will notice immediately that many people have neither the male nor the female brain. Their empathizing and systemizing abilities are pretty much balanced (E=S). They are the people in the pale grey zone. According to the EMB theory, people with autism or AS should always fall in the black zone.15 For males, it is just a small shift, from type S to extreme type S (from black dotted to black). For females, the shift is bigger, from type E (grey dotted) all the way to extreme type S (black).

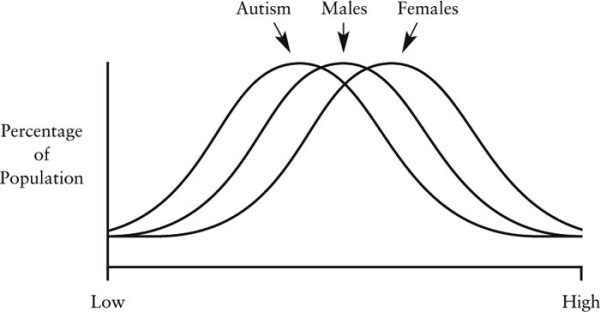

Male, female, and autism scores in empathizing

fig 9.

So what is the evidence in favor of the extreme male brain theory? I will briefly summarize the different lines of evidence here.

Impaired Empathizing

On the Empathy Quotient (or EQ), females score higher than males, but people with AS or high-functioning autism score even lower than males (Appendix 2).16 Moreover, on social tests such as the “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test (Appendix 1) or the Facial Expressions Test, females score higher than males, but people with AS score even lower than males.17

Females make more eye contact than do males, and people with autism or AS make less eye contact than males.18 Girls develop vocabulary faster than do boys, and children with autism are even slower than males to develop vocabulary.19 As we saw in Chapter 4, females tend to be superior to males in terms of chatting and the pragmatics of conversation, and it is precisely this aspect of language that people with AS find most difficult.20

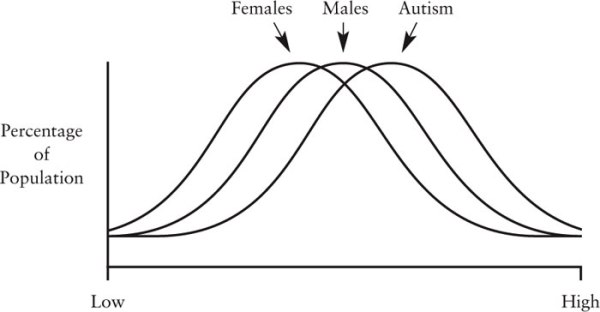

Male, female, and autism scores in systemizing

fig 10.

Females are also better than males at the Faux Pas Test, and people with autism or AS have even lower scores than males do.21 Girls also tend to be better than boys on standard “theory of mind” tests (tests which involve thinking about others’ thoughts and feelings), and people with autism or AS are even worse than normal boys at these tests.22 Finally, women score higher on the Friendship and Relationship Questionnaire (FQ) that assesses empathic styles of relationships. Adults with AS score even lower than normal males on the FQ.23

Superior Systemizing

On tests of intuitive physics, males score higher than females, and people with AS score higher than males.24 In addition, males are over-represented in departments of mathematics, and math is frequently chosen by people with AS as their favorite subject at school. As we saw in Chapter 2, boys prefer constructional and vehicle toys more than girls do, and children with autism or AS often have this toy preference very strongly. As adults, males prefer mechanics and computing more than females do, and many people with AS pursue mechanics and computing as their major leisure interests.

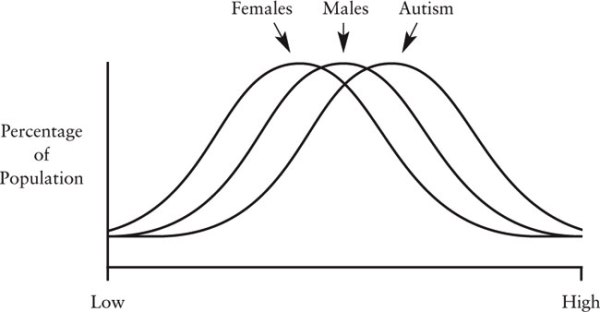

Male, female, and autism scores on the

Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ)

fig 11.

On the Systemizing Quotient (SQ), males score higher than females, and people with autism score highest of all (Appendix 3).25 On the Embedded Figures Task (EFT), a test of attention to detail, males score higher than females, and people with AS or HFA score even higher than males. The EFT (see Figure 6) is a measure of detailed local perception, a prerequisite for systemizing, but may also involve systemizing itself because there are rules that govern how the target can fit into the different possible slots (a bit like how to assemble a jigsaw or an engine).26 On visual search tasks, males have better attention to detail than females do, and people with autism or AS have even faster, more accurate visual search. This, too, is a prerequisite for good systemizing, while not comprising systemizing itself.27

Biological and

Family-Genetic Evidence

On the Autism Spectrum Quotient (the AQ), males score higher than females, but people with AS or HFA score highest of all (Appendix 4).28 When one looks at somatic (bodily) markers such as finger-length ratio, one finds that males tend to have a longer ring finger compared with their index finger; this finding is more pronounced in people with autism or AS.29 This finger-length ratio is thought to be determined by one’s pre-natal testosterone level. On the Tomboyism Questionnaire (TQ), girls with AS are less interested in female-typical activities.30 In one small-scale study, men with autism are also reported to show precocious puberty, correlating with increased levels of current testosterone.31

When one looks at the wider family as a clue to genetic influences, one finds that fathers and grandfathers of children with autism or AS (on both sides of the family) are over-represented in occupations such as engineering. These occupations require good systemizing, and a mild impairment in empathizing (as has been documented) would not necessarily be an impediment to success.32 There is a higher rate of autism in the families of those talented in fields such as math, physics, and engineering, when compared with those talented in the humanities. These latter two findings suggest that the extreme male cognitive style is in part inherited.33

But enough of data for a moment. I want now to put flesh on the bones, and tell you about a special person with AS who I had the privilege to meet.