1.2 The Cost-Benefit Principle

Nerida Kyle is a 23-year-old economics graduate who is about to start her first full-time job, working as a human resources manager in Houston. She likes her new apartment, but there’s no metro rail station nearby, buses only come rarely, and she’s too far from work to bike or walk. Nerida figures that she’ll need to buy a car to get to work because the only other alternative is a costly Uber ride each way. But before she heads out car shopping, she finds herself wondering: Is buying a car really my best choice?

The cost-benefit principle says that costs and benefits are the incentives that shape decisions. This principle suggests that before you make any decision, you should:

- Evaluate the full set of costs and benefits associated with that choice.

- Pursue that choice, only if the benefits are at least as large as the costs.

This principle says that Nerida should buy a car only if it yields benefits that are at least as large as the cost. Because the balance of costs and benefits define Nerida’s incentive to buy the car, this principle is sometimes best remembered by its conclusion: incentives matter.

The cost-benefit principle isn’t just relevant when deciding whether to purchase a car—it is relevant for literally any choice that you might consider. Look around, and you’ll see that decisions people make—where to go to lunch, whether to study economics, and what career to pursue—reflect their incentives, as they weigh the balance of costs and benefits.

Although it may seem obvious to do something only if the benefits exceed the costs, following the cost-benefit principle can be more challenging than it sounds. The trick is to think broadly about what constitutes a cost or benefit.

Quantifying Costs and Benefits

The hardest part of analyzing costs and benefits can be figuring out how to compare very different aspects of a decision. Let’s think about a simpler choice: You walk into a coffee shop and have to decide whether to buy a coffee. The chalkboard above the counter says that the price of coffee is $3.

The cost-benefit principle says that you should buy the coffee if the benefit is at least as large as the cost. The cost is pretty easy to quantify: It’s the $3 you’ll have to fork over. The benefits, however, are harder to measure. After all, how do you quantify the rich aroma of freshly ground coffee, the earthy richness of the first sip, and the caffeine-fueled jolt that follows?

How do you compare these benefits with three dollar bills? It may seem like that old expression—that you can’t compare apples and oranges. But actually, you can.

Convert costs and benefits into dollars by evaluating your willingness to pay.

There’s a simple trick that economists use: We convert each cost and benefit into its money equivalent. And that’s easier than you may think: Simply assess your willingness to pay. That is, ask yourself: What is the most that you would be willing to pay in order to obtain a particular benefit or to avoid a particular cost?

Let’s use this approach to quantify the benefits of coffee. Are you willing to pay $5 for it? If not, how about $4? Maybe $3? How about just $2? Maybe only $1? If you don’t like coffee, you probably aren’t willing to pay anything. If the most you are willing to pay is $4, then this is the dollar value of the benefits you receive from that coffee. You should always ask yourself about your willingness to pay before you look at the price. After all, you are simply trying to quantify the benefit you get from buying a cup of coffee, and that benefit depends on how delicious it is to you, not the price on the menu.

Let’s say that, like me, you are willing to pay up to $4 for a good cup of coffee. This doesn’t mean that you actually want to pay $4—of course you would prefer to pay a lower price, and you’re happy to see that it only costs $3. Now that you’ve answered the willingness-to-pay question, you have now quantified both the benefit ($4) and the cost ($3) of coffee in the same units (money). With costs and benefits in the same unit, it’s easy to apply the cost-benefit principle. In this case, the benefit exceeds the cost, so you should buy that coffee. Yum.

Money is the measuring stick, not the objective.

Some people worry that converting costs and benefits into their monetary equivalents reflects an unhealthy obsession among economists with money, or a belief that money is the only thing that matters. But that’s dead wrong. Money is simply a common measuring stick that allows you to compare a wide variety of costs and benefits, taking account of both financial and nonfinancial aspects of a decision. Economists are no more obsessed with money than architects are obsessed with inches; these are just how we take our measurements.

Money is just a tool for measuring value.

This simple trick, of converting costs and benefits into their monetary equivalents, will allow you to take account of a wide variety of nonfinancial issues. For example, you can factor in the degree of satisfaction you get from a cup of coffee, and the value of your time or effort in getting to the café. Any consequence of your choices can be a cost or benefit, as long as it has meaning to you.

Interpreting the DATA

What’s the benefit you get from Google?

What is the benefit to you from having access to Google? Even though the price of using Google is $0, the benefit from having all of the world’s information at your fingertips is much larger.

One way of answering this is to think about living without Google. Instead of Googling for answers, you would have to head to the library to answer most questions. Researchers have found that students can answer a typical question (“What scholarships are offered in the state of Washington?”) in about 7 minutes if they use Google, but it takes about 22 minutes to find the answer at the library. Once you factor in the number of searches people do, and put a value on the time saved, Google’s chief economist reckons these benefits from using Google add up to around $500 per year for the average American. Google illustrates an important point: The benefit you get from something can be unrelated to the price you pay.

The cost-benefit principle isn’t selfish—if you aren’t.

At first glance, it may seem like the cost-benefit principle says you should make selfish decisions. By this view, doing something nice—such as buying your friend a coffee—is all cost and no benefit. But this reasoning is wrong, and it comes from defining costs and benefits too narrowly. A careful cost-benefit analysis takes into account both the financial and nonfinancial aspects of a decision. Your innate generosity is an important nonfinancial aspect to consider. If you enjoy buying your friend a coffee—perhaps you like seeing them happy, or maybe you enjoy their company—then this is an important benefit that you need to account for.

How can you quantify this benefit? As with other nonfinancial benefits, you should think in terms of your willingness to pay: How much are you willing to pay so that your friend can enjoy a coffee? The more you enjoy doing nice things like this, the more you are willing to pay for it. Similarly, the benefit of donating time or money to a nonprofit will be high if the cause means a lot to you. You need to include these unselfish motivations in your cost-benefit calculations.

The cost-benefit principle isn’t just about you.

The key to using the cost-benefit principle properly is to think broadly about the full set of costs and benefits involved in your choices. When you account for your unselfish motivations, the cost-benefit principle will lead you to make unselfish choices.

Maximize Your Economic Surplus

When you follow the cost-benefit principle, every decision you make will yield larger benefits than costs. The difference between the benefits you enjoy and the costs you incur is called your economic surplus, and it is a measure of how much your decision has improved your well-being. Making good decisions is all about maximizing your economic surplus.

Follow the cost-benefit principle, and your choices will increase your economic surplus.

In fact, you generate economic surplus every time you make a decision in accord with the cost-benefit principle. Consider again what happened when you bought a cup of coffee: As a buyer, you gained something worth $4 to you (remember, that’s your willingness to pay for it), and in exchange, you transferred something worth only $3 (your money). This simple act of exchange generated an extra $1 worth of benefits to you! That’s your economic surplus.

Now think about the same transaction from the perspective of the seller—the entrepreneur who owns the café. If a cup of coffee costs $1 to make, then she has exchanged something worth $1 to her (some coffee beans, perhaps some milk and sugar, and a few minutes of a barista’s time) for something worth $3 (your money), generating $2 of economic surplus for her. Both buyer and seller are better off.

Let’s consider a more important example: Sony Music might offer you a job paying $45,000 per year, but you love the music industry so much that you would have accepted the job even if it paid only $35,000. If so, your new job yields you an economic surplus of $10,000. Of course, if Sony’s managers are following the cost-benefit principle, they offered you the job because they believe that you will generate benefits for them that exceed the $45,000 per year that they are offering to pay you. Perhaps by finding some great new bands, you are expected to generate an extra $75,000 per year in new revenue, generating $30,000 in economic surplus for them. The cost-benefit principle ensures that both you and Sony Music make choices that generate additional economic surplus, and avoid those that reduce your economic surplus.

Both buyers and sellers benefit from voluntary exchange.

In each of the above examples, both the buyer and seller benefited from the transaction, with each earning an economic surplus. If buyers and sellers always follow the cost-benefit principle, then each will choose to trade only if the benefits to them are at least as large as their costs. This ensures that all transactions will yield economic surplus. This idea of both sides benefiting from a voluntary exchange lies at the heart of all economic transactions.

This insight should shape how you think about economic transactions. Often noneconomists think about the economy like a sporting competition—that if you gain, I lose. It’s a colorful analogy—but it is false. It’s often more useful to think of economic transactions as being more like cooperation than competition. The café owner has something you really want (coffee), and you have something they really want (money). By cooperating, you can make each other better off. Similarly, you may have something Sony Music really wants (the ability to identify great bands, and in doing so you might generate $75,000 in new revenue for them) and they have something you want (a fun job and a good salary). Both buyers and sellers benefit from voluntary exchange, as long as they each follow the cost-benefit principle.

Sellers get money, buyers get the stuff they want. Both are better off.

Focus on Costs and Benefits, Not How They’re Framed

The cost-benefit principle says that you should make choices based on the underlying costs and benefits of the choice you face, rather than how they are described, or framed. But sellers will often try to make this difficult.

For instance, whenever a shirt is on sale, the price tag will show both the sale price and the original price. However, the amount of money you “save” is irrelevant. Instead, you need to ask yourself a simple question: Do the benefits of this shirt outweigh the cost (the sale price)? Similarly, many restaurants include one outrageously expensive item on the menu, even though no one orders it. (Lobster, anyone?) This overpriced lobster makes everything else on the menu look cheap by comparison. The restaurant hopes that with the money you “saved” by not ordering lobster, you’ll be tempted to order an appetizer, drink, or dessert. And some people do succumb to this temptation. This is a mistake: Your choice of food should depend on costs and benefits, and not something irrelevant, such as whether there’s an overpriced lobster on the menu.

Following the advice of the cost-benefit principle can be harder than it sounds. For instance, how would you respond to the following scenario:

Do the Economics

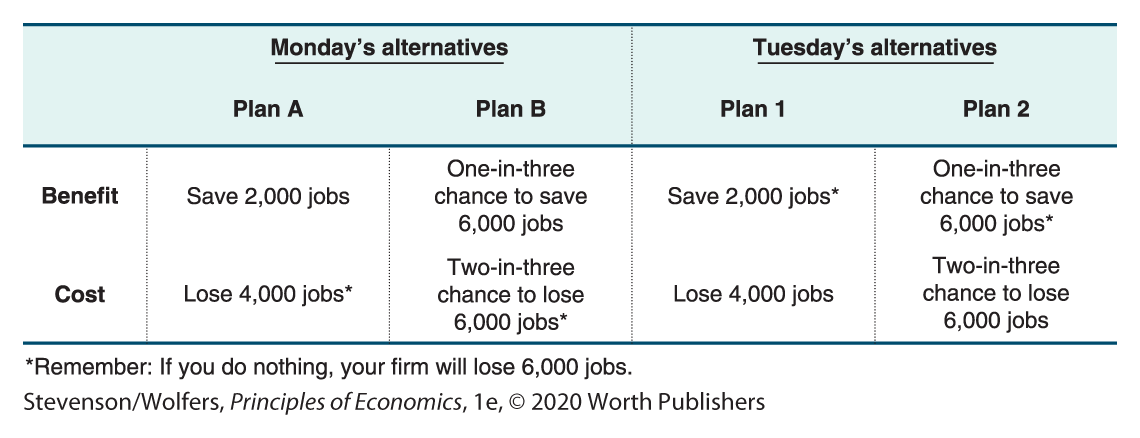

You’re the CEO of a large but struggling insurance company. Sales have fallen, and you need to cut costs in order to avoid losing money this year. You anticipate needing to fire 6,000 of your employees. Your management team has been exploring alternatives to this drastic action. During your Monday morning meeting, they suggest two possible plans:

Plan A: Saves 2,000 jobs.

Plan B: Has a one-in-three chance of saving all 6,000 jobs, but a two-in-three chance of saving no jobs at all.

Which plan would you choose?

Plan A Plan B

You arrive back at work on Tuesday, and your management team tells you that they have figured out a new set of alternatives to consider. They present the following two different alternatives:

Plan 1: Will result in the certain loss of 4,000 jobs.

Plan 2: Has a two-in-three chance of losing all 6,000 jobs, but a one-in-three chance of losing no jobs.

Which plan would you choose?

Plan 1 Plan 2

As the manager of your own life, you are going to confront high-stakes decisions just like this one.

Let’s now turn from using your gut to make decisions, to rigorously applying the cost-benefit principle. If you compare the choices you were offered on Monday with those offered on Tuesday, you will soon realize: They are identical! They were simply framed differently. That’s right: Since the total number of jobs at stake is 6,000, Plan A, which saves 2,000 jobs, is the same as Plan 1, which loses 4,000 jobs. Similarly, a one-in-three chance of saving 6,000 jobs in Plan B is the same as a one-in-three chance of losing no jobs in Plan 2.

So, if you chose Plan A on Monday, you also should have chosen Plan 1 on Tuesday, and if you chose Plan B on Monday, you also should have chosen Plan 2 on Tuesday. However, it’s possible that your choices between Monday and Tuesday were not consistent. If so, you’re not alone.

In fact, around 80% of people choose Plan A when offered a choice between Plans A and B, and about 80% of people choose Plan 2 when offered a choice between Plans 1 and 2. This means that most people change their decision depending on how it is described. And that’s a mistake.

Framing effects can lead you astray.

This is an example of a broader problem. Psychologists have documented that small differences in how alternatives are described, or framed, can lead people to make different choices. This phenomenon is known as the framing effect. But while the framing effect is common, it is not rational, and you don’t want your decision making to be this arbitrary. If you want to make good decisions that aren’t affected by how your choices are described, you should follow the cost-benefit principle. That is, you should evaluate the full set of costs and benefits of each alternative and only pursue those whose benefits are at least as large as their costs.

If you rigorously followed the cost-benefit principle, laying out the pros and cons of each plan, you would’ve ended up with an analysis like that in Figure 1.

Figure 1 | Costs and Benefits of Each Plan

When you articulate your costs and benefits this clearly, you’re less likely to fall prey to framing effects.

Applying the Cost-Benefit Principle

Let’s return to the decision we started with: Should Nerida buy a car or simply take an Uber to work every day? Since she’s trying to decide what to do over the next year, she should consider the costs and benefits that accrue over that year. Here are the costs she came up with:

- She can buy a 5-year-old Ford Focus for $10,000, however, she can sell it for $8,000 after using it for the year.

- She expects to drive 5 miles to and from work, 5 days a week, for 50 weeks per year (she takes 2 weeks off for vacation), and she anticipates getting 25 miles per gallon. Gas currently sells for $3 per gallon.

- Insurance costs $1,500 per year.

- She anticipates spending another $500 per year on repairs.

- Parking costs $5 per day.

The benefit of buying a car will be the Uber fares that she doesn’t have to pay. Each time she avoids taking an Uber to or from work, she’ll save $10 in fares. Over the course of a year, this will add up to $5,000. (For now, let’s say that this is the only benefit she gets from owning a car, because she can borrow her roommate’s car on the weekends.)

Figure 2 tallies up the costs and benefits. This is a useful exercise, highlighting just how expensive the total costs of driving are. Once Nerida considers all the hidden costs, the total cost of having her own car for one year adds up to $5,550! This annual cost is larger than the $5,000 benefit of not having to pay for an Uber each day. So while it feels decadent, Nerida takes an Uber to and from work every day. And this earns $550 worth of economic surplus—not a bad return for doing a few quick calculations!

Figure 2 | The Costs and Benefits of Car Ownership

EVERYDAY Economics

The true cost of car ownership

Are you surprised by how expensive car ownership is? In fact, for many people, it’s even more costly than this. You won’t make the right decision about whether to buy a car unless you account for the full set of costs and benefits associated with owning a car. To help you, the American Automobile Association (AAA) publishes a worksheet to help people figure out the true cost of car ownership. A typical family car costs $9,887 per year to run. Click through to https://exchange.aaa.com/automotive/driving-costs and calculate what it’ll cost you. The results might surprise you.

Calculate costs and benefits, relative to your next best alternative.

Let’s pause to notice something important about how Nerida calculated her costs and benefits. She’s comparing buying a car with taking an Uber to work instead. That is, she’s comparing one possibility—driving to work—with its next best alternative, which is taking an Uber. In fact, this is exactly the type of thinking that lies at the heart of our next principle: the opportunity cost principle. It’s an important principle because it’ll help you count your costs and benefits properly.

Plan B

Plan B