1.3 The Opportunity Cost Principle

Nerida has enjoyed a fair bit of success in her first three years of work. She has also noticed that many of the executives she admires have advanced degrees. In the long run, she might be even more successful if she studied for a Master of Business Administration (MBA). But is it worth it? The cost-benefit principle tells her that a good decision requires comparing the relevant benefits and costs. The benefits of an MBA are better career prospects. Indeed, careful studies show that MBAs earn around 10% more than comparable college graduates. But what are the costs?

Opportunity Costs Reflect Scarcity

The most obvious cost of an MBA is tuition, which is about $60,000 per year. But this isn’t the only cost. For instance, if Nerida pursues an MBA full time, she’ll have to quit her job. The more Nerida thinks about it, the more she realizes that some costs aren’t always obvious. And so she is left wondering: How can you be sure that your decisions reflect your true costs and benefits?

The opportunity cost of something is the next best alternative you have to give up.

Your decisions should reflect your opportunity cost, rather than just out-of-pocket costs, because the true cost of something is what you must give up to get it. This principle reminds you that whether you are deciding how to spend your money, your time, or anything else, you should think about its alternative uses. It tells you to assess the consequences of your choice relative to the best of your alternatives. The principle forces you to focus on the real trade-offs you face, and in doing so you will make better decisions. The opportunity cost principle is such a fundamental part of economic thinking that when economists say “costs,” we really mean opportunity costs.

Let’s now see how thinking about opportunity costs might lead you to assess your decisions differently.

People who haven’t studied economics tend to think about the cost of something as the out-of-pocket financial cost—how much money they have to take out of their back pocket to pay for it. But this can be very misleading. For instance, studying economics in the library until closing time every day doesn’t lead to any extra out-of-pocket costs. If this were the right way to think about costs, then you would be in the library studying economics whenever it’s open, since the benefit (learning more economics, which helps you make better decisions) surely offsets the out-of-pocket cost of zero. But this ignores other important costs. Your time is scarce, and so each hour spent studying economics has an opportunity cost, because it’s an hour that you can’t spend studying psychology, marketing, history, or math. It’s also an hour you can’t spend sleeping, working, or just enjoying life. You should only study another hour of economics if it yields benefits that are at least as large as those of the best of these alternatives.

The opportunity cost principle leads you to focus on the true trade-offs you face. If you make one choice (studying economics until 3 A.M.), what is the best alternative that you’re forced to give up? Just as the opportunity cost principle can help you better allocate your time (as in this example), it can help you better allocate your scarce money, attention, and resources.

The opportunity cost principle highlights the problem of scarcity.

If you ever think that a choice involves no costs, think again. Even if there’s no out-of-pocket cost, there’s always an opportunity cost. The logic is simple: Whenever you choose to do something, you are implicitly choosing not to do something else. Deciding to go to the movies? That’s a decision not to spend two hours preparing for class. The forgone opportunity to pursue an activity is the opportunity cost that you need to consider.

This opportunity cost arises because of a fundamental economic problem: scarcity. Your resources are limited—that is, they’re scarce. It’s not just that you have limited income, but you also have limited time (only 24 hours in a day), limited attention, and limited willpower. Any resources you spend pursuing one activity leaves fewer resources to pursue others. Scarcity implies that you always face a trade-off. Whenever you use any scarce resource—your time, money, attention, willpower, or other resources—there’s an opportunity cost.

EVERYDAY Economics

The opportunity cost is the road not taken

The opportunity cost principle even informs some poetry. Consider the last stanza of the poem “The Road Not Taken,” by the great American poet Robert Frost:

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference.

Frost’s traveler has come to a fork in the road, and faces a stark choice: which path to take. What is the opportunity cost of taking one path? The opportunity cost is the road not taken. Frost’s traveler takes “the one less traveled by,” and when he says that this “has made all the difference,” he is comparing it to his next best alternative. You can think of the opportunity cost principle as asking you to consider “the road not taken.”

Calculating Your Opportunity Costs

Remember, the opportunity cost of something is what you give up to get it. So, if you want to make sure that you are evaluating your opportunity cost correctly, you should ask yourself just two questions:

What happens if you pursue your choice?

What happens under your next best alternative?

That’s it. Now, let’s apply this principle to figuring out the true opportunity cost of pursuing an MBA.

What happens if Nerida pursues an MBA?

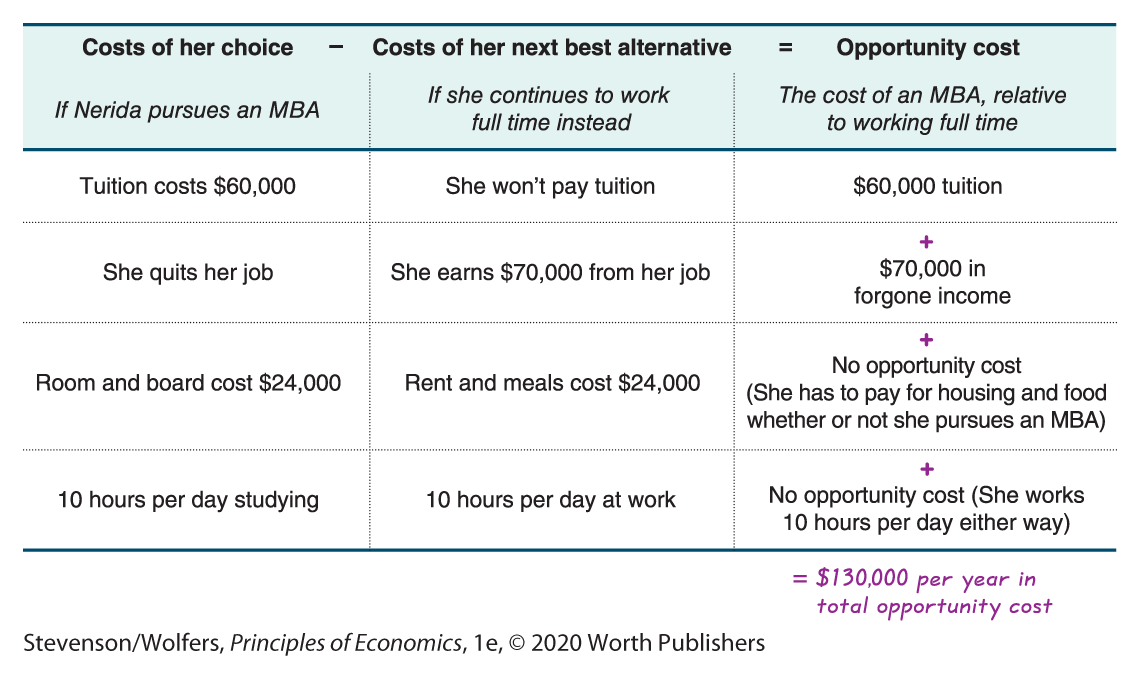

If Nerida pursues an MBA, she’ll quit her job, pay tuition, pay for room and board, and spend a lot of time studying. These consequences are listed in the first column of Figure 3.

What happens if Nerida pursues her next best alternative?

Nerida’s next best alternative is to keep working in her current job. If she chooses this route, she won’t have to pay tuition, she’ll earn $70,000 per year, she’ll still have to pay for rent and meals, and she’ll spend her days working. These consequences are listed in the second column of Figure 3.

Figure 3 | The Opportunity Costs of Pursuing an MBA (per year)

If the opportunity cost of something is what you must give up to get it, then it’s the difference between the consequences of making that choice and the consequences of the next best alternative. And so the opportunity cost of pursuing an MBA—shown in the final column of Figure 3—is equal to the first column minus the second column. We’ve found that the opportunity cost of pursuing an MBA is $130,000 per year, and so a two-year program comes at a cost of $260,000. This analysis reveals that Nerida should pursue an MBA only if the benefit exceeds the total opportunity cost of $260,000.

Your analysis has revealed four important lessons about opportunity costs:

Lesson one: Some out-of-pockets costs are opportunity costs.

The first cost that Nerida thought about was the $60,000 per year cost of tuition. Obviously this is an out-of-pocket cost. It is also an opportunity cost—she has to pay tuition if she pursues an MBA, but she wouldn’t incur this expense if she pursued her next best alternative, which is continuing in her current job.

Lesson two: Opportunity costs need not involve out-of-pocket financial costs.

But focusing too much on out-of-pocket financial costs might lead you to miss important opportunity costs. For instance, one of the biggest costs of pursuing an MBA is the salary that you forgo when you leave your job. Nerida is currently earning $70,000 per year, so going without this paycheck is a substantial opportunity cost!

Lesson three: Not all out-of-pocket costs are real opportunity costs.

Paying too much attention to out-of-pocket financial costs can also lead you to think about factors that aren’t actually relevant opportunity costs. For instance, if Nerida pursues an MBA, she’ll have to pay $24,000 per year for room and board. But room and board isn’t a cost that should be associated with getting your MBA, since even if you didn’t pursue an MBA, you would still have to pay for food and housing. If the expense is the same, and if you have to pay for it under either alternative, then it’s not an opportunity cost.

Lesson four: Some nonfinancial costs are not opportunity costs.

There are also nonfinancial costs of pursuing an MBA. For instance, Nerida will have to work hard, studying 10 hours per day. But in her current job, Nerida also works hard for 10 hours per day. Thus, relative to her next best alternative, the hard work demanded by an MBA program isn’t an opportunity cost.

EVERYDAY Economics

The true cost of college

You now have the tools you need to assess the true cost of your own college experience. I bet you thought about the cost of college before applying, and you probably looked up the numbers on your college’s website. But you were probably thinking about it wrong. That website probably listed the cost of things such as tuition, housing, meals, books, and health insurance—a list that is surprisingly unhelpful for evaluating the true opportunity cost of attending college.

For that, you need to know: If you weren’t attending college, what would be different? It’s true that you wouldn’t be paying tuition, so that’s an opportunity cost. But you would surely continue to eat, so the cost of food isn’t an opportunity cost. The same goes for the cost of rent and health insurance. College websites always manage to omit the biggest cost of going to college, which is that if you weren’t studying, you would probably be working and earning tens of thousands of dollars. Those forgone earnings are an important opportunity cost that you need to consider.

Yes, going to college involves a large opportunity cost. But hopefully applying the opportunity cost principle to your decisions while you’re in college will help you make sure that the benefit of your college education exceeds the cost.

In order to make a good decision, you always have to ask “or what?,” comparing your choice to its next best alternative.

The “Or What?” Trick

Here’s a simple trick to ensure that you are always applying the opportunity cost principle correctly: Whenever you pose a question, the word “OR” should be in the middle of your sentence. That is, when Nerida asks, “Should I get an MBA?” she is only asking half the question. She needs to add: “OR keep working?” The “OR” part of this sentence forces you to consider your alternatives, which is at the heart of the opportunity cost principle. So remember, always ask: “Or what?” Sometimes you’ll find that you can list more than one alternative. When this happens, just remember that the opportunity cost is the best of these alternatives. So you have a choice: Use this simple trick, OR sometimes make bad choices.

Do the Economics

What are the opportunity costs of each of the following choices?

Should you hang out with your friends on Saturday afternoon?

Or what? Or should you study for Tuesday’s exam?

Should you devote a lot of time to an extracurricular activity and aim for a top leadership position?

Or what? Or should you study a lot more and aim for straight A’s?

Should you do an unpaid internship this summer?

Or what? Or should you continue waiting tables?

Should you hire your best friend to work in your family business?

Or what? Or should you hire someone else?

Should you invest your savings in the stock market, where your savings can grow a lot in value over the long run, but where they can also fall in value?

Or what? Or should you invest your savings in the bank, where the value of your savings will stay roughly the same?

Should your online store export its goods, selling them to people overseas?

Or what? Or sell them only to people domestically instead?

Should you spend all of your income?

Or what? Or should you save some of your income, to spend it in the future?

Your actual answers to these questions are unique to you, but they still make up some of the biggest costs you’ll face. That’s why you’re learning the tools of economics, so that you can make better decisions for your own unique life.

How Entrepreneurs Think About Opportunity Cost

The opportunity cost principle is also critical to how entrepreneurs evaluate whether or not to start a business. Just as you shouldn’t be overly focused on out-of-pocket costs, entrepreneurs know to look beyond their business revenues and financial costs. They also understand that starting a new business imposes some hard-to-see opportunity costs. The “or what” approach makes these costs clearer. Starting a new business requires confronting the following two questions:

Should you start a new business or stay in your current job?

Starting a new business means quitting your job and, thus, giving up your regular paycheck. These forgone earnings are the opportunity cost of an entrepreneur’s time.

Should you invest your money in the new business or leave it in the bank?

Investing your money in your business means not investing it in the bank, and so not earning interest. This forgone interest is the opportunity cost of an entrepreneur’s capital.

So when you are thinking about starting a new business, it isn’t enough just to figure out whether you’ll earn a financial profit. Starting a business is only a good idea if the benefit it yields—those financial profits—are large enough to offset the opportunity cost of the income you forgo by investing both your time and your money into this business, rather than your next best alternatives.

You Should Ignore Sunk Costs

Sometimes when you’ve spent a lot of time or money on a project, you may think: “I can’t stop now; I’ve already put so much into this project.” But this is a mistake. When the time, effort, and other costs you put into the project cannot be reversed, they are referred to as sunk costs. And good decision makers ignore sunk costs. Why? The opportunity cost principle asks you to compare the consequences of your choice with the consequences of the next best alternative. Since sunk costs can’t be reversed, you’ll incur those costs under either scenario, which means that they are not opportunity costs. Thus, you should ignore sunk costs. There’s another way to say this: Let bygones be bygones.

Unfortunately, many of us find it hard to ignore sunk costs in our everyday lives. Have you ever seen anyone stay in an unhappy relationship because they’ve already spent so much time working on it? Or perhaps you’ve seen someone stay in a college major, job, or career that they hate, figuring that it’s the right thing to do, given how much time and effort they have put into it. Sometimes corporate executives make similar mistakes, throwing good money after bad, in the hope that an investment project will eventually pay off.

Do the Economics

It is easy to fall for the sunk-cost fallacy. Think about the following scenarios:

- Yesterday you bought a Halloween costume for $35 to wear to a friend’s Halloween party. But today you’re feeling sick, and as you’re getting dressed to go to the party, you realize that you won’t enjoy it. Do you head to the party?

- You paid $13 for movie tickets. But 30 minutes into the film, you’ve seen enough: The acting is terrible, the plot is predictable, and the jokes are cringe-worthy. Do you stay for the last hour?

- You found a great deal for spring break: a $700 package deal to Puerto Rico. You immediately buy the package and tell your friends about it. Unfortunately, by the time they call, tickets are sold out. Instead, your friends decide to drive to Miami, where you can all stay for free with your best friend’s uncle. You would prefer to be with your friends, but the $700 ticket is nonrefundable. Do you go to Puerto Rico?

Applying the Opportunity Cost Principle

The opportunity cost principle is an incredibly powerful tool that can help you better understand all sorts of decisions. The following examples illustrate just how important it is in explaining the decisions that people make.

Why do more people go to the movies during an economic downturn?

Earth’s economy was weak in 2009, but Pandora’s was booming.

During the recent economic downturn, the major film studios braced themselves for a major decline in business. But they shouldn’t have. Why? The most important cost of seeing a movie isn’t the $13 price of the ticket. Instead, it’s the opportunity cost of your time. The movie takes two hours, and you could spend this time doing something else. Perhaps you could be working instead of seeing the movie. But when the economy is weak, there are fewer jobs, and there is often less work to do, and so the opportunity cost of your time is lower. Or perhaps the alternative to the movie is going to a party. But fewer people throw parties when the economy is weak, so your alternative may be a night watching television. Because the opportunity cost of time is lower during an economic downturn, people choose to see more movies. In fact, a weak economy is often good news for the movie industry.

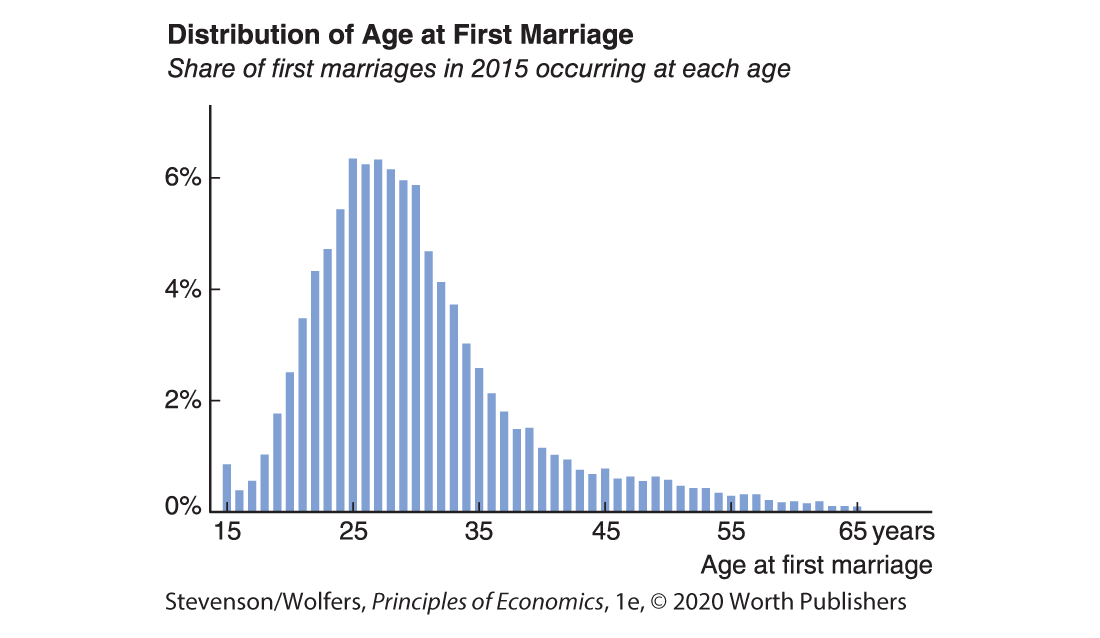

Why not get married as soon as you turn 16?

Many high school students get involved in romantic relationships, but very few get married at age 16. Why? The choice you face is: Should I get married or keep searching for a better match? At age 16, you may have had only a couple of romantic entanglements, and so the possibility that later on you’ll meet someone who’s an even better match is pretty high. That is, the opportunity cost of marriage—the opportunity to search for an even better partner—is high. By your twenties and thirties, you have more life experience and have met people from many spheres of life. While there’s always the possibility that you’ll find someone even better later on, the opportunity cost of getting married is likely to be much lower.

Data from: U.S. Census Bureau.

Why do the terminally ill want unproven experimental drugs?

Most people are unwilling to take unproven experimental drugs, because they fear that the drugs will do more harm than good. But people with terminal illnesses sometimes plead with their doctors to be allowed to be part of a new medical trial. Why? For healthy people, the choice they face is between taking part in a risky experiment and continuing with their healthy, happy lives. For those with terminal illnesses, the alternative to the risky experiment is continued illness and probable death. Due to this lower opportunity cost, people with severe illnesses are willing to take risks that others are not.

Why I don’t eat free doughnuts.

Early-morning business meetings often include a tray of doughnuts on the conference table. These doughnuts are delicious, and they’re free, but I never eat them. Why? In order to stay healthy, I try to limit myself to only one indulgence each day. So I face a choice: should I eat the doughnut or enjoy a bowl of ice cream tonight? And I love ice cream. So while the financial cost of the doughnut is $0, it’s still too expensive, because the opportunity cost of a doughnut is an even more delicious bowl of ice cream.

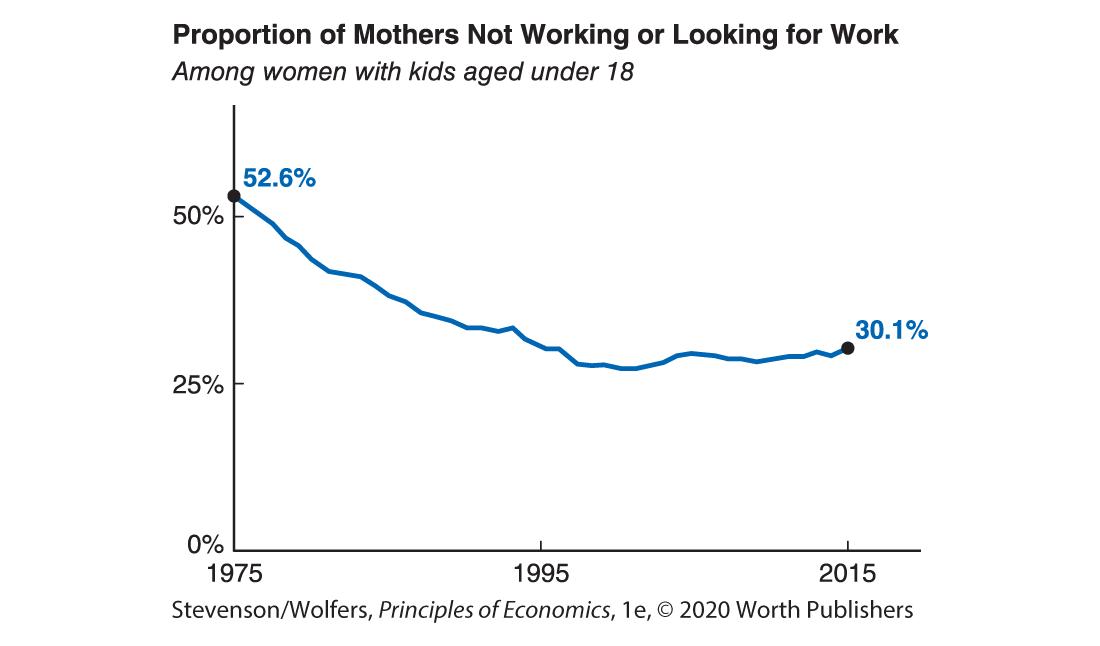

Why are there fewer stay-at-home moms?

In 1975, more than half of all mothers stayed out of the labor force. Since then, things have changed, and the most recent data suggest that only 30% of moms stay at home. Why? Most mothers face a choice between staying at home and working for pay. Over recent decades, there has been a sharp rise in women’s wages, and since 1975, the annual earnings of a typical full-time female worker rose by around $10,000 (after adjusting for inflation), even as male earnings barely changed. Consequently, the opportunity cost of being a stay-at-home mom has risen. As this opportunity cost has risen, fewer women have chosen to stay at home. Instead, more women are now choosing to combine motherhood and working for increasingly better pay.

Data from: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

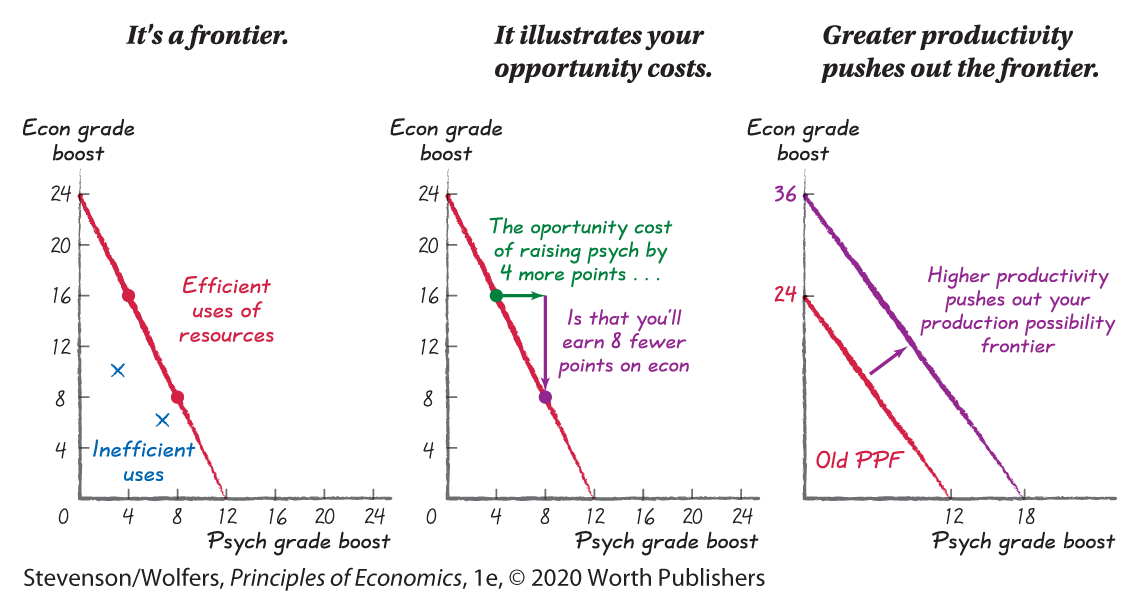

The Production Possibility Frontier

Sometimes you’ll find it useful to visualize your opportunity costs. That’s what the production possibility frontier is for—it maps out the different sets of output that are attainable with your scarce resources. It illustrates the trade-offs—that is, the opportunity costs—you confront when deciding how best to allocate scarce resources like your time, money, raw inputs, or production capacity.

The production possibility frontier illustrates your alternative outputs.

Let’s see how this applies to your study time. If you have three hours per night to study, you can allocate that time between studying economics and studying psychology. Perhaps each extra hour per night you devote to studying economics will raise your econ grade by 8 points, while allocating that time to studying psychology instead will boost your psych grade by only 4 points.

Effectively you’re the CEO of a grades-producing factory whose inputs are study time and whose outputs are grades. You can devote your factory’s resources to boosting your econ or psych scores to varying degrees. At one extreme, you could spend all three hours studying economics, which would raise your econ grade by 24 points (and psych by nothing). At the other extreme, you could spend all three hours studying psychology, which would boost your psych grade by 12 points (and econ by nothing). In between there’s a bunch of other possibilities for allocating your study time, each of which corresponds to a point on your production possibility frontier. Together, these points form a frontier, shown in Figure 4 as a straight line (although in many other cases, your production possibilities frontier may be a bowed-out curve). We call this a frontier, because it describes the most that you can produce given your current circumstances. If you waste your resources, or use them inefficiently, you won’t even hit this frontier, and you’ll end up producing less of each output than you otherwise could.

Figure 4 | The Production Possibility Frontier

Moving along your production possibility frontier reveals your opportunity costs.

When you’re on your production possibility frontier, you can’t produce more of one output unless you produce less of the other. Moving along your production possibility frontier highlights this opportunity cost: Every hour you devote to studying psychology (which boosts your psych grade by 4 points) is one less hour you can devote to economics (which would have boosted your econ grade by 8 points). As a result, the opportunity cost of adding 4 more points to your psych grade is earning 8 fewer points on econ.

Productivity gains shift your production possibility frontier outward.

So, what if you want to produce more than is possible with your production possibility frontier? Well, you’ll have to change something. One way to do that is to discover new production techniques that allow you to do more with the same amount of inputs. For example, if you uncover more effective study habits (my advice: reading the text before class is much more productive than cramming weeks later) you might be able to increase the grade boost that comes from each hour you spend studying. This increase in productivity shifts out your production possibility frontier (or PPF for short). But even if you get better at studying psych and econ, your resources are still limited; and so there’s still an opportunity cost to your time.

Recap: Evaluating Either/Or Decisions

Let’s take a breath, and take stock. The two principles that we have studied so far provide useful guidance whenever you are trying to decide whether or not to do something—such as whether to get an MBA, whether to get married, whether to go to a movie, and whether to look for a job. Since you either choose to do these things or not, we call these “either/or” choices. The cost-benefit principle says: Do it if the benefits are at least as large as the costs. But what are the costs? The opportunity cost principle says that the true cost of something is the best alternative you give up to get it. Taken together, these principles say: You should pursue your choice if it yields benefits that are at least as large as the opportunity cost, which is your next best alternative.

But many choices are “how many” rather than “either/or” choices. Consider some examples: How many classes should you take? How many workers should you hire? How many children should you have? When you face “how many” questions, you’ll need to use one more core principle, the marginal principle, which will allow you to simplify even incredibly complicated “how many” choices into a series of much simpler “either/or” choices. This will help you answer a much wider range of questions, since you’ve already figured out how to make good “either/or” choices.