6.3 Quantity Regulations

Just as the government might set the maximum or minimum price for the market, it can also set a quantity regulation—a maximum or minimum quantity that can be sold. A mandate requires you to buy or sell a minimum amount of a good. A health insurance mandate requires consumers to purchase health insurance. A housing mandate occurs when developers want to build new housing and they are told that they must also build (hence, supply) a certain amount of low-income housing. A binding mandate—meaning that without the mandate the equilibrium quantity would be lower—on buyers increases the quantity buyers demand. A binding mandate on sellers increases the quantity sellers supply. In both cases, the amount of the good or service sold increases to the mandated amount.

Quotas set a limit on the maximum quantity of a good that can be sold. Quotas can be on buyers—for instance, many states that have legalized marijuana limit the amount that people can buy per day. These limits are designed to reduce the quantity sold by reducing demand. Quotas, however, are more frequently placed on suppliers. For instance, New York City has a taxi quota, a cab is legal only if its owner holds a “medallion,” and only 13,600 of these have ever been issued. Consequently, even during rush hour, you won’t see more than 13,600 taxis on the road in New York City. Of course, taxis now have competitors like Uber and Lyft. To understand what motivated Uber and Lyft to enter the market and how they changed the market for rides, you need to understand what a quota on sellers does to the quantity supplied and the prices charged. So let’s take a closer look at a quota in the housing market, and then we’ll look at what happened in the taxi market.

Quotas

Whenever you drive around a quiet, leafy neighborhood, it usually isn’t that way by chance. Often, zoning laws explain why there are houses with backyards instead of apartment buildings. Zoning laws articulate the type and quantity of housing that can be built in an area. Many U.S. cities and suburbs have zoning laws. The result is usually less housing and higher prices. Why? Because zoning laws effectively impose quotas, limiting the number of housing units that can be built. Let’s use the supply-and-demand framework to see why this happens.

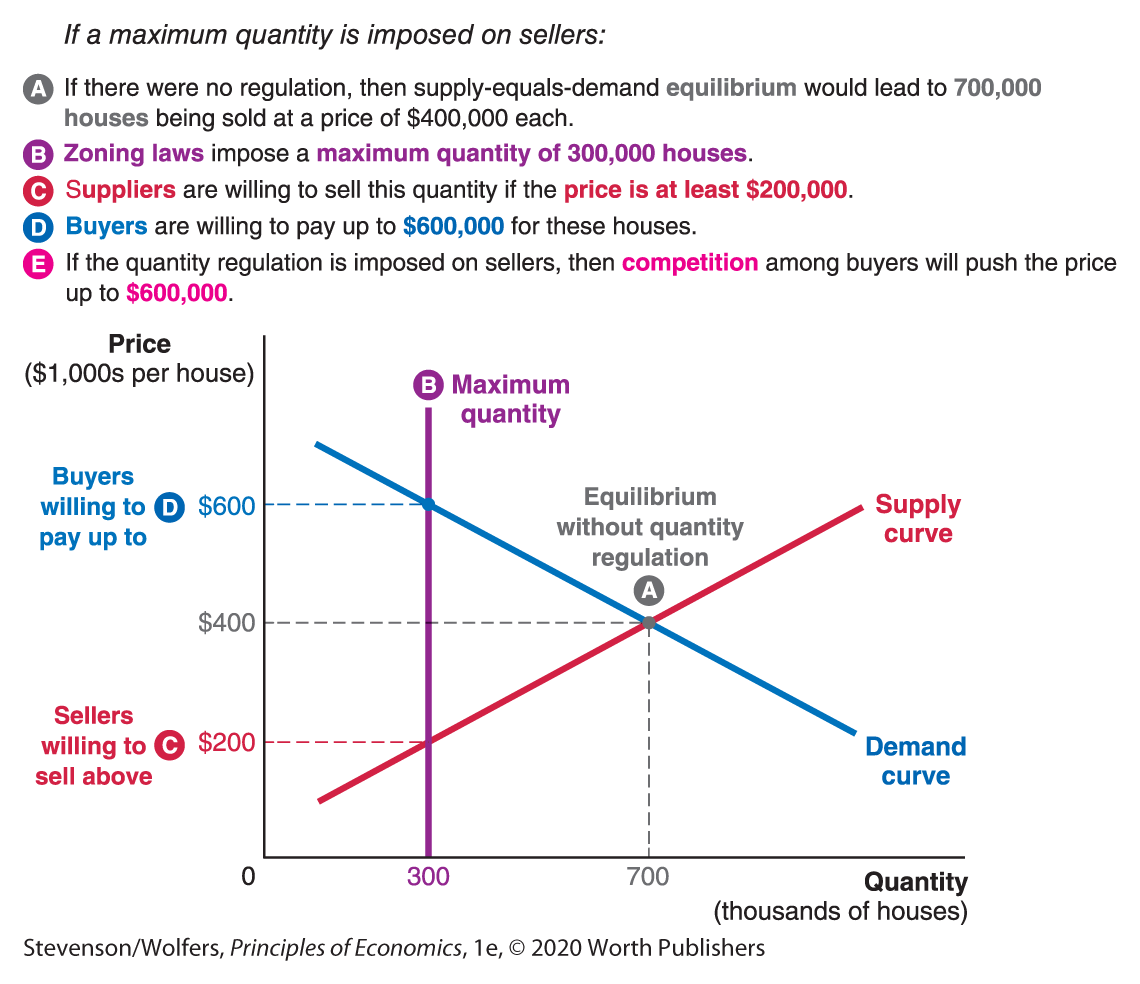

Seattle is a city with zoning regulations that limit the development of housing. Figure 7 illustrates the consequences of housing quotas in Seattle, showing the supply and demand curves for housing in Seattle. If there were no government regulation, then you would expect the supply-equals-demand equilibrium to occur, and there would be 700,000 housing units in Seattle, selling for $400,000 each.

Figure 7 | Zoning Laws and the Seattle Housing Market

Quotas raise prices.

Figure 7 shows that zoning restricts development to a maximum of 300,000 houses. Because consumers want to purchase more housing and sellers want to sell more housing, the quota will be binding—meaning that the quota will determine the quantity sold. Suppliers are willing to supply a quantity of 300,000 houses as long as the price is at least $200,000 per house. You can see this in Figure 7 by looking at the intersection of the supply curve with the maximum quantity, which occurs at a price of $200,000 per house.

However, with only 300,000 houses available, buyers are willing to pay up to $600,000 for these houses. You can see this in Figure 7 by looking at the intersection of the demand curve with the maximum quantity. If sellers sell houses for less than $600,000, there will be more buyers than sellers. Because buyers can demand as much housing as they want, but sellers are limited to selling only the 300,000 houses, buyers will compete with each other for the limited available housing, bidding up the price until it reaches $600,000, where the quantity demanded is equal to the maximum quantity that can be supplied due to the zoning regulation. Even though sellers would be willing to sell for less, competition among buyers for scarce goods leads them to pay higher prices.

Due to zoning laws, homeowners in Seattle can sell their houses for $200,000 more than they could without the laws (prices rose from $400,000 without the quota to $600,000 with the quota), and they enjoy a less crowded environment. However, fewer people are able to afford to live in Seattle, and those who do have to pay more for housing.

This has a direct effect on people like Indira, who would like to move to Seattle. Indira is a software engineer living in Houston, who would like to accept a job offer at Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle to advance her career. Due to zoning restrictions, she can’t find a house in the area in her price range. So she stays in Houston and works remotely for Amazon. This arrangement allows her to keep enjoying lower-cost housing, but it also makes it harder for her to bond with her colleagues, limiting her ability to make new contributions and get promoted.

EVERYDAY Economics

How Uber and Lyft undermined government taxi quotas

Quotas set by the government limit taxis in many cities. As you’ve just seen, a quota that restricts supply leads to higher prices and a lower quantity sold. You also saw that suppliers would be willing to sell for less—meaning that the marginal cost of providing another taxi ride is well below the price in the market with quotas. That gap between price and marginal cost creates an incentive for potential sellers to find a way around the regulation. Uber and Lyft did just that. They entered the market as an alternative business—ride sharing—and they argued that ride-sharing businesses weren’t covered by the government quantity regulations.

Researchers have shown that the supply of drivers in a city rose by 50% and that incomes for taxi drivers fell as prices paid for rides fell on average. So part of what ride-sharing companies did was undermine regulations that limited supply and therefore drove prices down. But there was another effect that pushed prices in the other direction—ride-sharing companies improved the technology matching potential riders to potential drivers. You no longer have to stand in the rain hoping to hail a taxi, but you can stay where it’s dry and look for a ride on your phone. The technological change increased the productivity of drivers—they spend more time driving people and less time looking for people to drive—and by improving the marginal benefit of a ride, the technological change increased demand from consumers.

Quotas are quite common.

Analyzing quantity regulations can be useful for understanding an enormous array of government regulations, since quantity restrictions are quite common beyond what you might think of as “traditional” markets. Consider the following quotas:

- Immigration quotas effectively limit the supply of workers;

- China lets families have a maximum of two children;

- Trade quotas limit the number of certain goods that can enter a country, and customs regulations limit what kinds and how many souvenirs you can bring back from abroad;

- The U.S. government has capped the number of medical residents, or doctors in training, that it funds;

- Environmental regulations often limit the quantity of pollutants that firms can release;

- During the recent drought, California banned irrigating medians along streets;

- “Hunting season” limits the number of days in which hunting is legal, and amount of game that can be hunted;

- The U.S. Department of Transportation limits the number of hours truck drivers can work each week.

In each of these cases, these restrictions reduce the quantity of each activity.

Compare price and quantity regulation.

Let’s summarize the steps we’ve taken to analyze a quantity regulation, and compare it with price regulation. The first step is the same in both cases: Begin by figuring out if the regulation is binding. Does it establish a maximum quantity below (or a minimum quantity above) the equilibrium? If the regulation isn’t binding, it won’t affect market outcomes. But if it is binding, you need to determine the new price and quantity.

With price regulation, the new price will be the regulated price, and you need to find the quantity sold at that price. The quantity sold is determined by the forces of supply and demand and is the minimum of the quantity demanded or the quantity supplied. With quantity regulation, the quantity is determined by the regulation and the forces of supply and demand determine the price. With a quota on sellers, the resulting price will be determined by what buyers are willing to pay for the limited quantity available. A quota on buyers, however, will lead to the price at which suppliers are willing to supply the restricted quantity that buyers demand.