7.2 Measuring Economic Surplus

We’ve just seen that economic surplus plays an important role in economic policy debates. And so if you want to influence these debates, you’ll need to know how to measure economic surplus. That’s our next task.

Consumer Surplus

When you gain economic surplus from buying something, economists refer to it as consumer surplus, because you’re earning that surplus in your role as a consumer. You gain consumer surplus when you buy something for a cheaper price than the marginal benefit you get from it.

Consumer surplus is your marginal benefit, less the price.

Your marginal benefit is your willingness to pay for these jeans.

Let’s take an everyday example. You’re at the mall looking for new jeans, and you find the perfect pair of Levi’s, although the price tag is missing. After trying them on, you decide you’re willing to pay up to $80 for them. You ask the clerk to look up the price and learn some good news: The price is only $50. It’s good news, because you were willing to pay up to $80 for the jeans, but you got them for only $50. It’s like you’re $30 ahead! That $30 gain is the consumer surplus you get from this transaction.

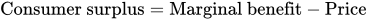

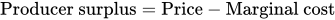

Consumer surplus describes the gain from buying something at a price below the highest price you were willing to pay (which is your marginal benefit). It’s the marginal benefit you’ll get from those jeans, less the price you pay. You can see it graphically in Figure 1, and you can measure it as:

Figure 1 | Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is the area below the demand curve and above the price.

So far, we’ve analyzed the consumer surplus of a single transaction—it’s the marginal benefit you get, less the price you pay. What about the consumer surplus of all purchases in a market? Let’s take a look at the market demand curve.

Figure 1 shows the market demand curve for jeans. Recall from Chapter 2 that the demand curve is the marginal benefit curve. This means that each point on the demand curve reveals an individual buyer’s marginal benefit. And so for any individual purchase, the consumer surplus gained is the marginal benefit (which is given by the height of the demand curve) less the price. You can see the consumer surplus from your single purchase shown as the difference between the point on the demand curve where the marginal benefit is equal to $80 minus the price of $50. Add up this gain for each pair of jeans sold, and you’ll end up with the entire area under the demand curve and above the price, out to the quantity purchased. This reveals that total consumer surplus in a market is the area under the demand curve and above the price, out to the quantity sold.

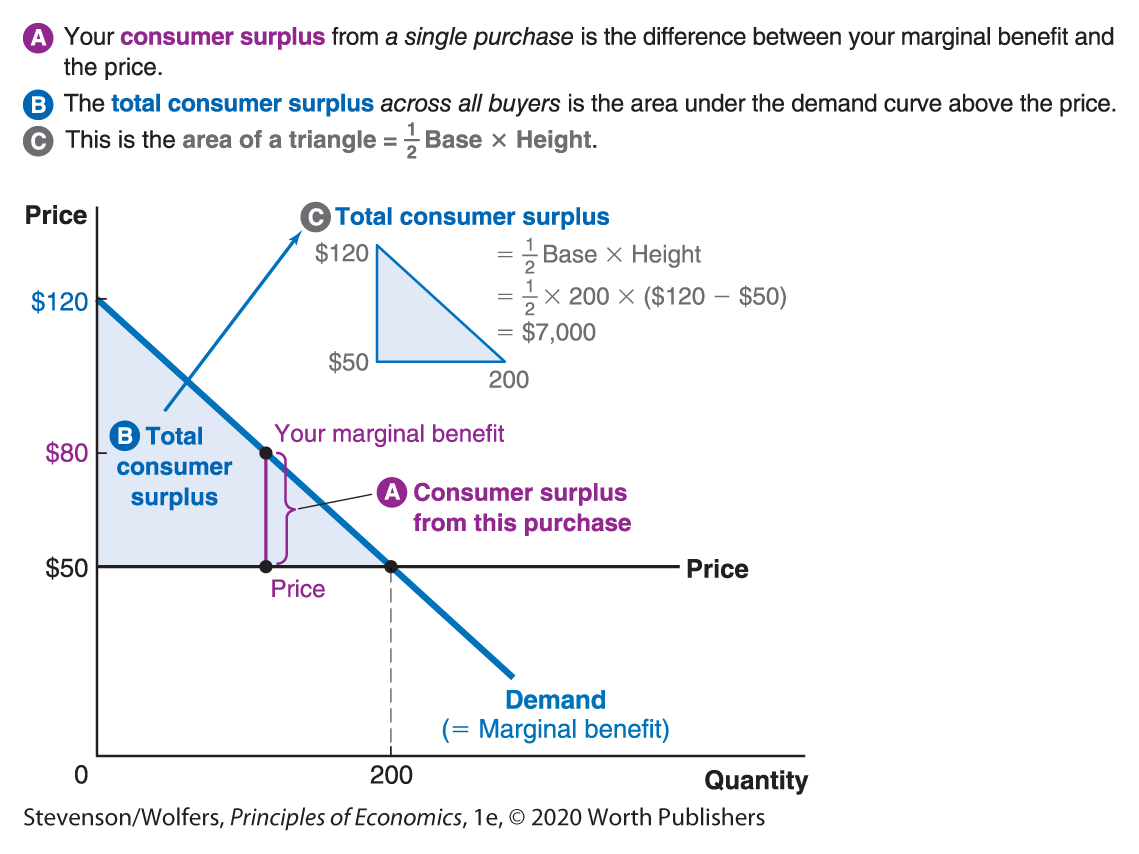

The area of a triangle is half the base, times the height.

This is the moment you thought might never arrive: High school geometry will be useful. Here’s why: When the demand curve is a straight line, consumer surplus is a right triangle. So figuring out total consumer surplus means figuring out the area of that triangle, which is half the base, times the height.

Do the Economics

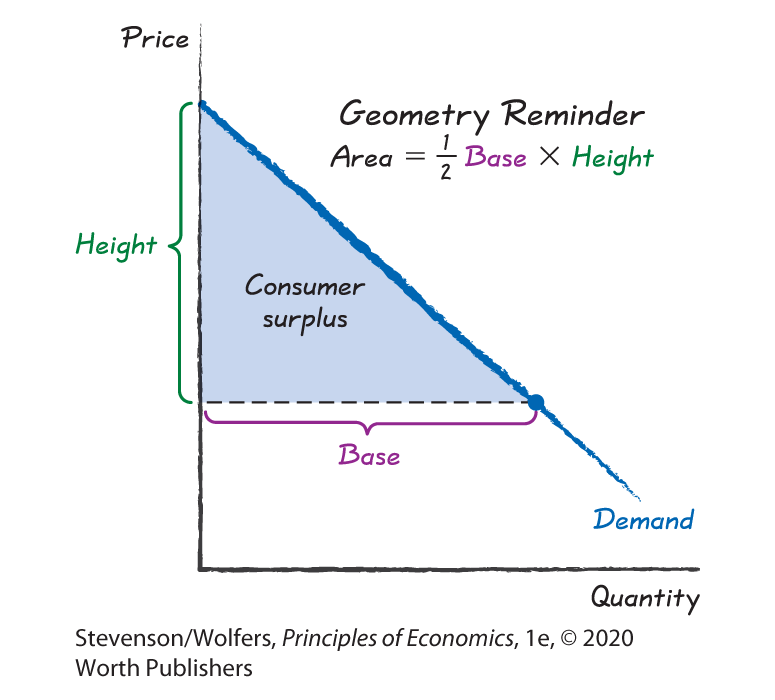

What’s the consumer surplus of a song? Let’s try to work it out. Take Rihanna’s song “Work,” which she sang with Drake. She sold 10 million copies of this song for roughly $1.29 a copy. If half the people who bought this song said in a survey that they would have been willing to pay at least $2.29 for it, then we have two points on the demand curve for this song. If we connect these two points to get an estimate of the demand curve for this song, we’ll discover that the demand curve cuts the vertical axis at $3.29.

Consumer surplus is the area under the demand curve and above the price, out to the quantity sold. Zoom in on that triangle:

That’s it. Rihanna’s song created around $10 million in consumer surplus for her fans. Thanks, Rihanna!

You earn consumer surplus on all but your last purchase.

Some students are puzzled by the idea that consumer surplus is the difference between their marginal benefit and the price, while the Rational Rule for Buyers (introduced in Chapter 2) says to keep buying until price equals marginal benefit. But there’s no contradiction. The Rational Rule tells you to keep buying jeans until the marginal benefit of the last pair is equal to the price. If you bought four pairs, then your fourth and last pair yields a marginal benefit equal to their $50 price tag. That means you won’t earn any consumer surplus on that last pair. But the marginal benefit from your first pair is likely much higher—you don’t have to wear shorts! Perhaps your marginal benefit was $80 for that first pair, exceeding the $50 price, and therefore, yielding a healthy consumer surplus. Likewise, you also may earn consumer surplus on the second and third pair you buy. The point is, even if you earn no consumer surplus on the last item you purchase, you’ll likely earn consumer surplus from all of your preceding purchases.

You enjoy a lot of consumer surplus in your life.

Consumer surplus is important because the price you pay for something is often a poor indicator of the benefits you get from it. Consider water. Because it’s so cheap, your marginal gallon of water is probably used for something pretty unnecessary, like running the faucet while brushing your teeth.

Not every use of water saves your life.

But how much would you be willing to pay for the half-gallon a day you need to stay alive? Thousands of dollars, right? Yet your water bill shows that you pay only pennies for it. The fact that water is cheap doesn’t mean that it’s not valuable; rather, it means that you’re enjoying thousands of dollars of water-related consumer surplus.

The same idea applies to health care. Antibiotics that sell for only a few dollars can prevent a simple infection from becoming life threatening. The vaccinations you got as a baby protect you from polio, tetanus, and hepatitis, yet they cost your parents very little. And if you’ve ever had a friend or relative survive a life-saving operation, you’ve probably enjoyed a lot of surgery-related consumer surplus. Even if the surgery cost thousands, that price is small relative to the benefit of saving a loved one.

Each of these examples shows that you’ll enjoy a lot of consumer surplus in your life. Indeed, that’s a theme we’ll continue to explore in the next case study.

Interpreting the DATA

Consumer surplus on the internet

Perhaps you started your day by checking your e-mail. Maybe you skimmed Instagram, Facebook, Snapchat, or Twitter. Hopefully you looked up the weather forecast before heading out. You might have listened to Spotify on the way to class. While you (hopefully!) didn’t look at your phone during class, when it ended you may have used Google to look up a troubling concept. And later in the evening, you might have used Yelp to choose where to get dinner, and checked Google Maps for directions. Or maybe it’s a quiet night, so you headed home to browse BuzzFeed, read the news, and then watch videos on YouTube. How much did you pay to use each of these sites?

Nothing. Nada. $0.

If you used the price to measure the economic importance of your favorite websites, you’d infer that they’re worth nothing. But that would be a mistake. It’s a mistake, because it fails to account for the enormous consumer surplus that a good website generates.

To measure this consumer surplus, think about how much you would pay each year to have access to Google. Likewise, you can evaluate your willingness to pay for Wikipedia, Facebook, and all the other internet services to figure out the marginal benefit you get from your favorite websites. The consumer surplus you get from them is this marginal benefit, less the price, which is $0.

Economists have made such calculations, considering different ways of measuring the marginal benefit people get from these services. They’ve looked at how much people used to spend on internet access when it was a newer, more expensive technology; at how much people used to pay for non-internet based substitutes like encyclopedias; at how much time people spend on the internet; and at what people say they would have to be paid to give up access to internet services. While estimates vary, one reasonable estimate is that access to the internet collectively brings the average person around $2,600 per year worth of consumer surplus. Consumer surplus reveals that these websites are extremely valuable, even though most of this value isn’t reflected in their low or nonexistent price.

Producer Surplus

Consumer surplus tells us about the gains from trade that buyers get. But buyers aren’t the only ones who benefit from a transaction; sellers also gain something. When you gain economic surplus from selling something, economists refer to it as producer surplus, because you’re earning that surplus in your role as a producer. You gain producer surplus when you sell something at a higher price than the marginal costs you incur.

Producer surplus is the price, less the marginal cost.

Let’s analyze what happens when you buy a pair of Levi’s for $50, but this time, we’ll focus on the producer’s perspective. For Levi’s, the marginal benefit of selling you those jeans is the $50 price you paid for them. And the marginal cost is the $35 worth of extra denim, thread, and labor it took to make that extra pair of jeans. Levi’s is thrilled to get $50 in return for $35 worth of denim, thread and labor. It’s thrilled because producing and selling those jeans made Levi’s $15 better off. This $15 is the producer surplus that Levi’s gains from this transaction.

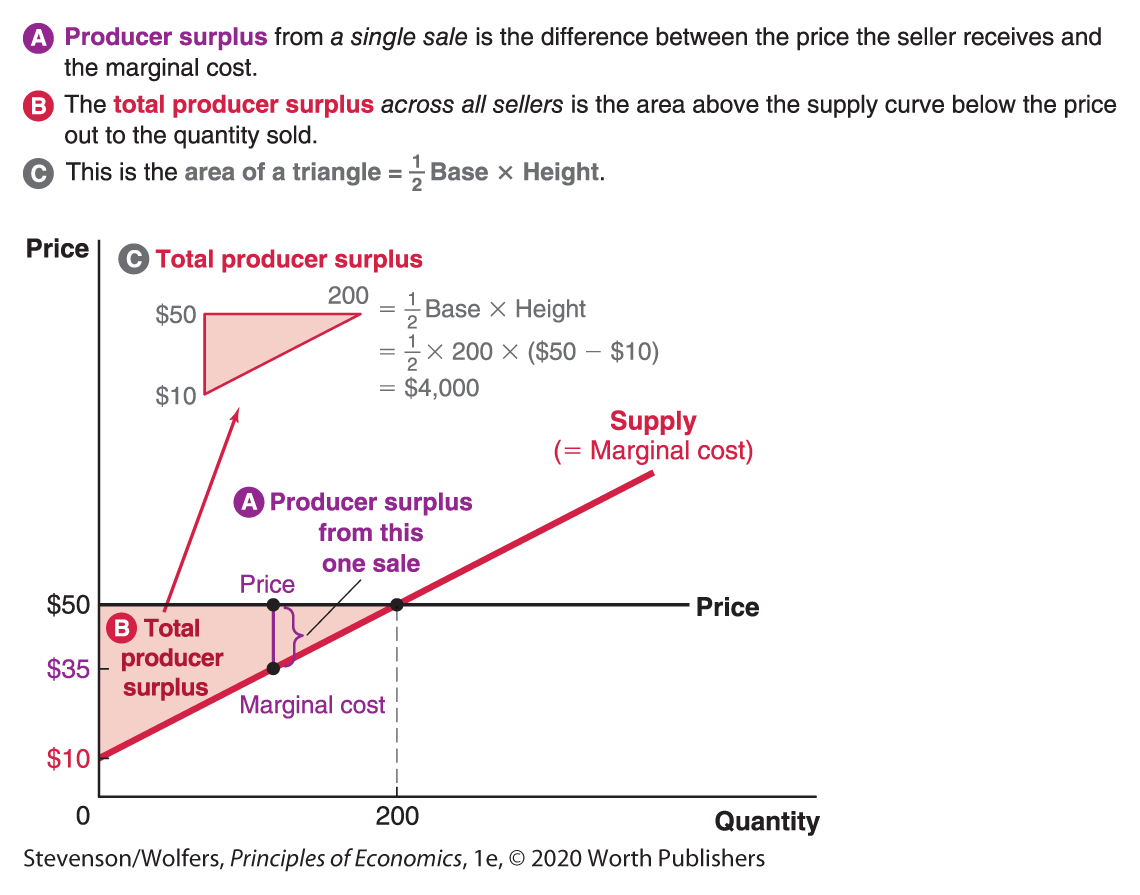

Producer surplus describes the gain a producer gets from selling something at a higher price than necessary for them to want to supply the item, which is its marginal cost. More generally, the producer surplus a seller gains from a transaction is the price they receive less the marginal cost. And so, you can measure it as:

Producer surplus is the area above the supply curve and below the price.

So far, we’ve figured out the producer surplus from Levi’s selling you one pair of jeans. What about the total producer surplus from all the jeans sold by all producers? The producer surplus from any individual transaction is the price less marginal cost. This leads to a simple graphical representation: Total producer surplus in a market is the area below the price and above the supply curve, out to the quantity sold, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 | Producer Surplus

To see why, recall from Chapter 3 that the supply curve is also the seller’s marginal cost curve. This means that each point on the supply curve reveals a seller’s marginal cost. And so for any given sale, a seller gains producer surplus equal to the price, less their marginal cost, and the marginal cost is the height of the supply curve. Add this producer surplus up across all jeans sold, and you’ll end up adding the entire area above the supply curve and below the price, out to the quantity sold.

You earn producer surplus on all but your last sale.

As a seller, your producer surplus is the difference between the price and your marginal costs. But the Rational Rule for Sellers in Competitive Markets (in Chapter 3) says to keep selling until price equals marginal cost. At first glance, this might confuse you into thinking that you won’t earn any producer surplus if you follow this rule. But that’s not right. Instead, realize that the Rational Rule says to keep selling until price equals marginal cost. This means that price is equal to marginal cost only for the last (or marginal) pair of jeans you sell. With an upward-sloping marginal cost curve, the marginal cost of every other pair of jeans you make is lower, and so you’ll earn a healthy producer surplus on all but the last pair of jeans you sell.

EVERYDAY Economics

The producer surplus of work

My first job was babysitting and I loved it. I got to eat the family’s snack food, have fun playing with the kids, then watch TV after they went to bed. The pay was also great. Here’s what I never told the parents who hired me—I would have done it for half the pay. Have you ever had a job where you would have done it for less than you were actually paid? If so, then you earned producer surplus at your job.

Here’s the logic: As a worker, you’re a supplier, selling your labor, and your hourly wage is the price you’re selling it at. What’s the relevant marginal cost? Applying the opportunity cost principle, it’s the value of your next best use of that hour. If the wage exceeds how much you value this alternative use of your time, then you’re earning producer surplus.

In one survey, around one-third of American workers said they would stay in their job even if their salary were cut by 25%. A typical economics graduate with a few years of work experience earns about $60,000 per year, and so this would mean sticking with your employer even if you were paid $15,000 per year less. So we can infer that many folks are earning at least $15,000 per year in producer surplus!

Voluntary Exchange and Gains from Trade

Next time you go shopping, pay attention to how polite everyone is. When I last bought a pair of jeans, I handed over my $50 and said to the seller, “thank you,” and the seller said to me “thank you.” We now understand why. I said thank you, because the store gave me a pair of jeans that I valued at more than a $50 bill. I was grateful to gain some consumer surplus. And the seller said thank you because I gave them money that they value more than the stitched denim they were handing over. They were grateful to gain some producer surplus. This is more than just politeness—it reveals a deeper economic truth: Voluntary transactions create both consumer and producer surplus. This means both the buyer and the seller gain from trade. The big idea here is that buying or selling goods and services isn’t a zero-sum game in which one person wins at the other person’s expense. Instead, trade is a win-win situation, creating gains for both the buyer and the seller. That’s why economists talk about the gains from trade.

Voluntary exchange ensures both buyer and seller enjoy gains from trade.

Trade generates gains for both the buyer and the seller because it’s based on voluntary exchange, where buyers and sellers exchange money for goods only if they both want to. And you only want to buy or sell stuff if it’ll make you better off.

Think about it: As a buyer following the cost-benefit principle, you’ll only buy a pair of jeans if the marginal benefit you receive is at least as large as the price you pay. That is, you’ll only buy something if it yields consumer surplus. Likewise, a supplier following the cost-benefit principle will only sell jeans if the price is at least as large as their marginal cost. That is, suppliers only produce stuff if they expect it’ll generate producer surplus. And so voluntary exchange ensures that both buyer and seller enjoy gains from trade (or at least that neither is made worse off).

This leads to an underappreciated perspective. You might be used to thinking about markets as being mostly about competition. But voluntary exchange generates economic surplus for both buyers and sellers, and so perhaps it’s more useful to think about markets as facilitating cooperation. Just as your purchase of Levi’s jeans helps boost its bottom line, Levi’s production of jeans has also helped you line your bottom.

This doesn’t mean that consumers and producers share equally in the gains from trade. But even if the gains are unequal, as long as both buyers and sellers are well-informed and follow the cost-benefit principle, neither will engage in a trade that makes them worse off.

Economic surplus is marginal benefit less marginal cost.

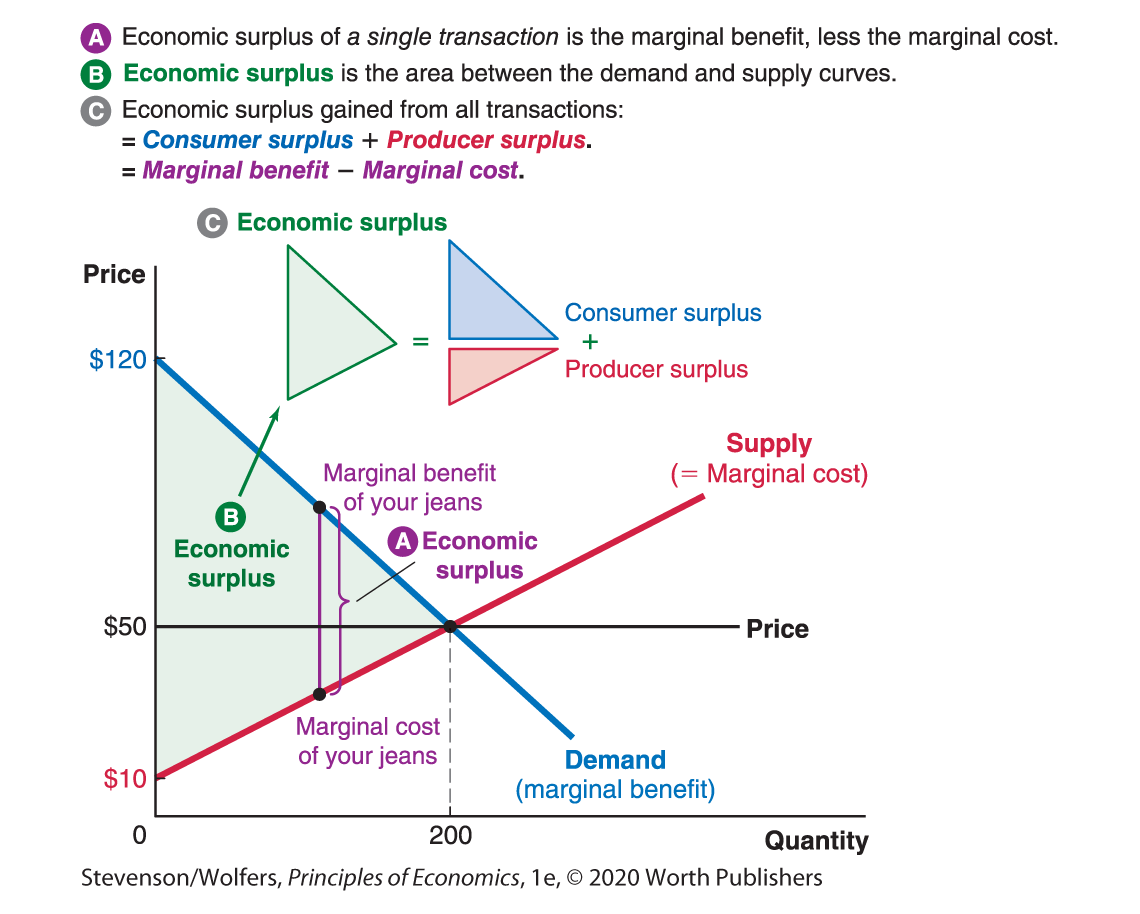

Let’s put the pieces together. The economic surplus generated by a transaction is the sum of consumer surplus enjoyed by the buyer (the marginal benefit, less the price) and the producer surplus accruing to the seller (the price, less the marginal cost). Add them up, and the economic surplus generated by a transaction is the marginal benefit less the marginal cost:

For instance, when you buy a pair of jeans that brings you $80 worth of benefit, and it cost Levi’s only $35 worth of denim, cotton, and labor, the transaction creates $45 in economic surplus.

Economic surplus is the area between the demand and supply curves.

Total economic surplus, or gains from trade, across a whole market is the consumer surplus triangle (the area below the demand curve and above the price) plus the producer surplus triangle (the area above the supply curve and below the price). Add them up and you’ll discover that economic surplus is the area between the demand and supply curves, to the left of the quantity bought and sold, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 | Economic Surplus

Alternatively, you can think of the economic surplus from a single transaction as being the marginal benefit less the marginal cost. Add this up across all items purchased, and it’s the difference between marginal benefits (the demand curve) and marginal cost (the supply curve) across all items bought and sold. And that’s why economic surplus is the area between the demand (or marginal benefit) curve and the supply (or marginal cost) curve, out to the total quantity.

Okay, so now you should have a good sense of how to measure economic surplus—it’s the marginal benefit to the buyer less the marginal cost to the seller. This means that on a graph, it’s the area between the demand and supply curves, to the left of the quantity sold.

Now let’s use these tools to assess the efficiency of markets.