7.3 Market Efficiency

Markets are the central organizing institution of our lives. They determine what products are made, how much is produced, who makes what, who gets what, and what the price will be. Markets determine your income and what you can afford to buy. It isn’t always this way. In centrally planned economies like Cuba, North Korea, and to an extent China, the government decides what gets made, and who gets what.

It’s time to ask: Are markets a good idea? Why should markets play such a central role in our lives? The central argument is that markets yield more efficient outcomes. That is, markets create the largest possible amount of economic surplus by providing efficient answers to three central questions: (1) who makes what; (2) who gets what; and (3) how much gets bought and sold? Let’s explore how markets answer each of these questions.

Question One: Who Makes What?

Think about the supply side of the economy: Millions of businesses produce a dizzying array of products. How do we know which businesses should produce which products? Which firms should produce a lot, and which should produce only a little? Who should be in business, and who should go kaput? While it’s nearly impossible for any individual to find the best answer, a well-functioning market can figure it all out. Let’s explore how.

Efficient production minimizes costs.

Efficient production occurs when we produce a given level of output at the lowest possible cost. This requires allocating production so that each item is produced at the lowest marginal cost.

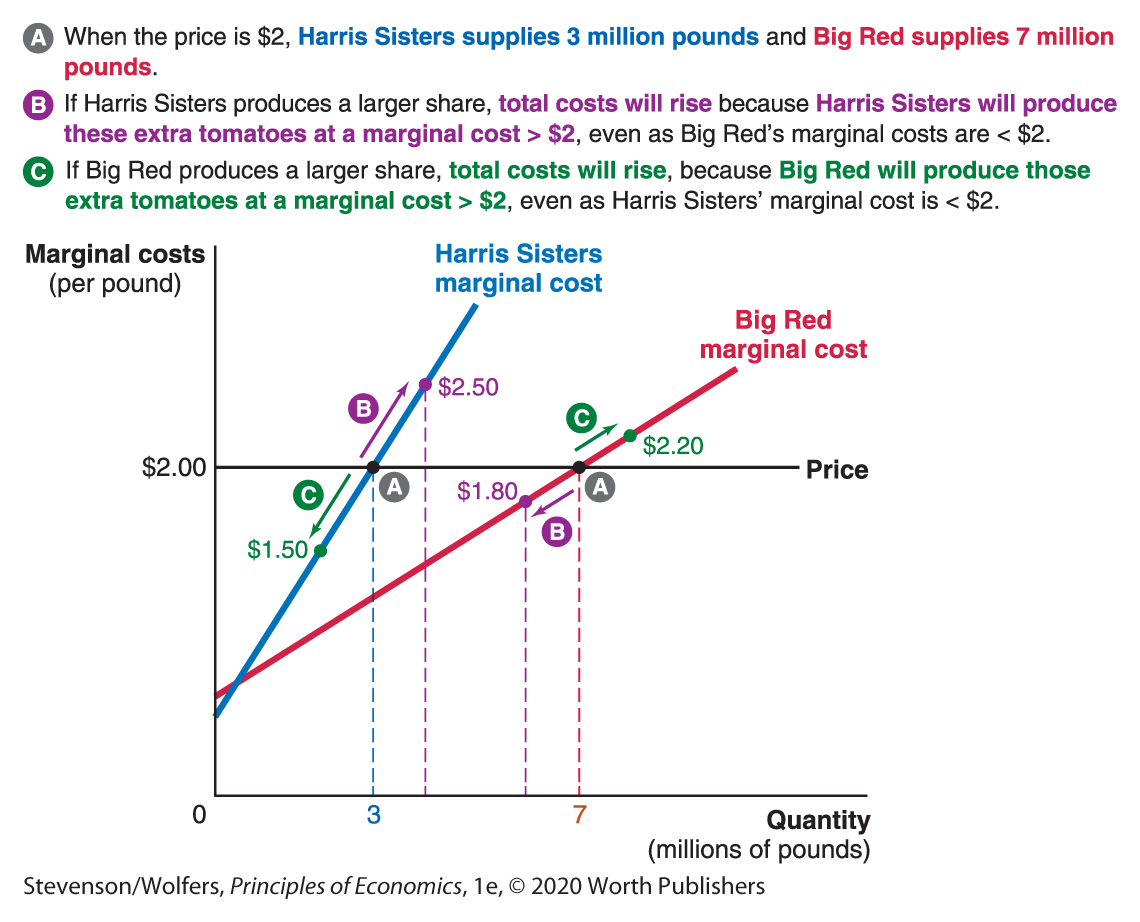

Consider two important suppliers in the market for tomatoes. Harris Sisters is a small family farm in North Carolina, while Big Red is a large industrial farm in California. The marginal cost curve of each farm is shown in Figure 4, along with the current price of tomatoes, which is $2 per pound.

Figure 4 | Which Firm Should Supply How Much?

A business’s marginal cost curve is also its individual supply curve, and so when the price is $2 per pound, Big Red supplies 7 million pounds of tomatoes, and Harris Sisters supplies 3 million pounds. This is efficient production, because there’s no way to produce 10 million pounds of tomatoes at a lower cost. That is, supply and demand lead to efficient production.

To see this, consider the alternatives.

What if you ask Harris Sisters to produce a greater number of tomatoes and Big Red to produce fewer? The total cost of producing those 10 million tomatoes will rise. It’ll cost Harris Sisters more than $2 per pound to produce those extra tomatoes (perhaps as much as $2.50 per pound) even though Big Red had previously produced those extra tomatoes at a marginal cost less of than $2 per pound (perhaps as low as $1.80). So this alternative is inefficient, because it raises the total cost of producing these 10 million pounds of tomatoes.

Alternatively, what if you ask Harris Sisters to produce fewer tomatoes and Big Red to produce more? That’s also inefficient. The problem is that when Big Red produces more tomatoes, its marginal cost exceeds $2 per pound (perhaps it’s as high as $2.20), while Harris Sisters could have produced those extra tomatoes at a marginal cost below $2 (perhaps as low as $1.50). And so this alternative plan is also costlier.

Putting the pieces together, we’ve discovered that any production plan other than the one caused by the forces of supply and demand would raise costs. Amazingly enough, supply and demand lead Harris Sisters and Big Red to divvy up total production in such a way as to ensure that it occurs at the lowest possible cost! This is how competitive markets lead to efficient production in which each item is produced at the lowest possible cost.

Markets distribute production across firms in a way that minimizes costs.

It’s worth pausing to think about how amazing this is. The farmers at Big Red and Harris Sisters don’t know each other, and indeed, they’ve never even been in touch. Neither has an interest in ensuring that ten million pounds of tomatoes is produced as cheaply as possible. Instead, each of them pursues their own self-interest, choosing the production levels that maximize their own profits. Yet this self-interest leads these businesses to split production in a way that ensures that together they produce the industry’s total output at the lowest possible cost.

In sum, perfectly competitive markets ensure efficient production so that every good is produced by the supplier who can do so at the lowest possible marginal cost.

Question Two: Who Gets What?

Let’s now turn to the demand side of the economy. There are millions of people who all want to consume the myriad products the economy produces. Who should get what? To take just one example: Who should get a lot of tomatoes, and who should get just a few? Intuitively, we want the tomatoes to go to people who will really value them. After all, there’s no point in sending tomatoes to folks like my uncle who despises them.

Efficient allocation maximizes benefits.

An efficient allocation occurs when goods are allocated to create the largest economic surplus from them, which requires that each good goes to the person who gets the highest marginal benefit from it (at least as measured by how much they are willing to pay).

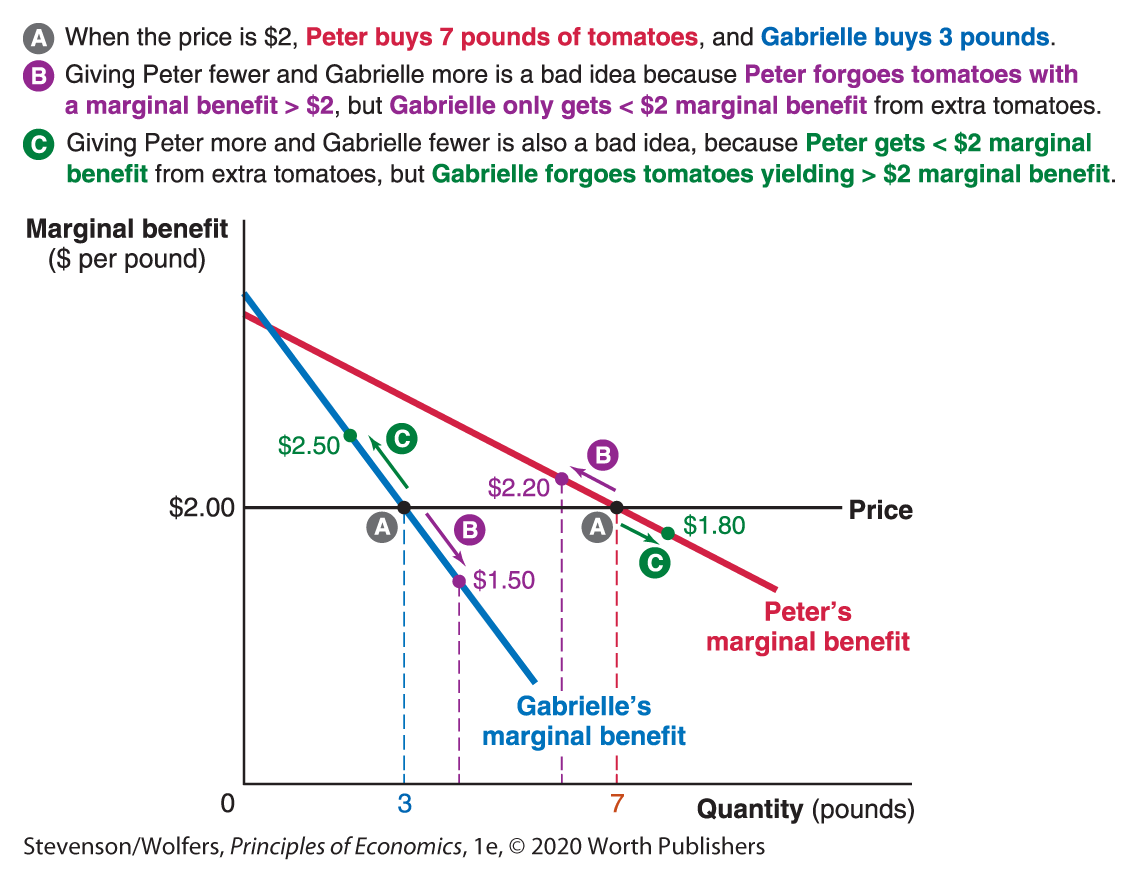

Consider two tomato buyers, Gabrielle and Peter. Their marginal benefit curves are shown in Figure 5. Remember, these marginal benefit curves are also their individual demand curves, and so when the price is $2, Peter will buy 7 pounds of tomatoes, and Gabrielle will buy 3 pounds.

Figure 5 | Who Should Get How Much?

This is an efficient allocation, because each tomato is going to the person with the highest marginal benefit, ensuring that they generate the largest economic surplus. That is, supply and demand leads to an efficient allocation.

To see this, consider alternative allocations.

You could give Gabrielle some of Peter’s tomatoes. But that will decrease economic surplus, because the extra benefit to Gabrielle is less than the forgone benefit to Peter. The reason is that Gabrielle’s marginal benefit from extra tomatoes is less than $2 (perhaps as low as $1.50), while Peter is forgoing tomatoes from which he would get a marginal benefit that’s greater than $2 (perhaps as high as $2.20).

Alternatively, you could try to give Peter some of Gabrielle’s tomatoes, but this will also decrease economic surplus, because Peter’s marginal benefit from getting extra tomatoes is less than $2 (say, $1.80), while Gabrielle will forgo tomatoes from which she would get a marginal benefit that’s greater than $2 (perhaps $2.50).

We’ve discovered that the forces of supply and demand lead Gabrielle and Peter to divvy up these tomatoes in a way that ensures each tomato goes to the person who’ll get the highest marginal benefit from it (at least as measured in terms of willingness to pay). Any other allocation would reduce the total amount of economic surplus. It follows that competitive markets lead to an efficient allocation of goods in which each item winds up being sold to the person who’ll get the highest marginal benefit from it.

Markets allocate goods to those with the highest marginal benefit.

This is an extraordinary outcome. Neither Gabrielle nor Peter know each other, and indeed, they’ve never even spoken. But by each pursuing their self-interest, they’ve ensured that each tomato is allocated to the person who would enjoy the highest marginal benefit from it. This same logic applies to how markets allocate billions of tomatoes (and countless other items) across millions of buyers—the competitive market will allocate them to the folks with the highest marginal benefit. As each buyer pursues their own self-interest, the market allots each tomato to the person who gets the largest marginal benefit, at least as measured by their willingness to pay.

Question Three: How Much Gets Bought and Sold?

So far we’ve seen that whatever quantity of goods is produced, competitive markets lead to efficient production, which means those goods are produced at the lowest overall cost. Competitive markets also lead to efficient allocation, which means those goods are allocated to the people who get the largest marginal benefit from them.

Our final step is to analyze the quantity of goods that is bought and sold. We’ll assess whether the forces of supply and demand lead to the efficient quantity, which is the quantity that produces the largest possible economic surplus.

The Rational Rule for Markets says to produce until marginal benefit equals marginal cost.

Let’s start by figuring out the efficient quantity of tomatoes: How many tomatoes will produce the largest possible economic surplus for society as a whole? Since this is a “how many” question, the marginal principle says to focus on the simpler question: “Should we produce one more tomato?” Next, apply the cost-benefit principle, which says that yes, an extra tomato will increase economic surplus, as long as the marginal benefit is at least as large as the marginal cost.

Put the pieces together, and we get the following very helpful rule.

The Rational Rule for Markets: To increase economic surplus, produce more of an item if the marginal benefit of one more is greater than (or equal to) its marginal cost.

It follows that we’ll get the largest possible economic surplus if the market keeps producing until marginal benefit equals marginal cost. That is, the efficient quantity occurs where:

Supply and demand produce the surplus-maximizing quantity.

There is no one in charge of the market; somehow the forces of supply and demand naturally produce this surplus-maximizing quantity. Recall that equilibrium occurs where supply equals demand. In a well-functioning market, the supply curve is also the marginal cost curve, and the demand curve is also the marginal benefit curve. And so supply-equals-demand equilibrium occurs at the point where marginal benefit equals marginal cost. As Figure 6 illustrates, this is the point that creates the largest possible economic surplus.

Figure 6 | What Quantity Yields the Most Surplus

To see why, realize that if sellers produce less than the equilibrium quantity, the marginal benefit to buyers exceeds the marginal cost to sellers, and so we could increase economic surplus by increasing production. On the flipside, if sellers produce more than the equilibrium quantity, the marginal cost to sellers exceeds the marginal benefit to buyers, and so we could increase economic surplus by decreasing production.

It follows that the quantity that maximizes economic surplus is also the equilibrium quantity that results from the forces of supply and demand. That is, competitive markets lead to the efficient quantity of any good.

It’s as if all economic activity is being directed by an invisible hand.

Let’s put all of this together, because it’s a pretty extraordinary finding. Organizing our economy—deciding who makes what, who gets what, and how much to make of each good—is a task of astonishing difficulty. It’s so difficult that no committee of expert economists could ever figure out how to do all of this efficiently.

Yet millions of buyers and sellers, guided by nothing but their own self-interest, end up doing what an expert committee cannot. They produce the quantity that maximizes the total amount of economic surplus. They ensure that this quantity is produced at the lowest marginal cost. And they ensure that each good goes to the person who draws the largest marginal benefit from it, as revealed by their willingness to pay. The market achieves an efficient outcome, despite the fact that no market participant is trying to achieve that goal. Instead, as each person pursues their independent self-interest, they guide the market toward an efficient outcome. As Adam Smith, who was one of the founders of economics, noted, it is as if all economic activity is guided by an “invisible hand.”