9.1 Comparative Advantage Is the Foundation of International Trade

What drives people in different countries to trade with each other? As a buyer, why do you buy goods imported from other countries? As a manager, why would you buy raw materials from foreign rather than domestic producers? As a producer, why would you sell your output to foreigners rather than just locals?

The most obvious reason to buy goods from abroad is that you can get a better deal. You will choose to import—that is, buy goods or services from foreign sellers—when foreign products are cheaper than their American-made equivalents.

Likewise, American businesses choose to export—that is, sell their goods or services to foreign buyers—when they can get a better price than if they just sold them in America. Indeed, many businesses find more people willing to pay a high price for their products when they supply them to the global market comprising all 8 billion people on the planet, rather than just the 330 million Americans in their domestic market.

Comparative Advantage and International Trade

You can get a better deal by trading with foreigners for the same reason that you get a better deal by trading with people within your country. The reason is comparative advantage.

You have a comparative advantage in a task if you can complete it at a lower opportunity cost than someone else. Instead of making everything yourself, you should specialize in those activities where you have a comparative advantage, because this means your opportunity cost is lower than others. And you should rely on your trading partners for the other stuff, where their opportunity costs are lower.

When we each specialize according to our comparative advantage, we’re each doing more of what we’re relatively good at and trading with others so we’re buying the things they’re relatively good at. The result is that we can both end up better off. Specializing according to comparative advantage means that we can produce more together than we can apart. (This should all be familiar from the first half of Chapter 8. If it’s not, go back and read it right now. The idea of comparative advantage is so important to international trade that I’ll wait here until you’re done.)

Geography is irrelevant.

This idea of assigning tasks to those with the lowest opportunity cost is no less persuasive if the folks with the lowest opportunity cost happen to live in another country. After all, an international border is just an arbitrary invisible line. So the same logic and calculations that suggest you’ll be better off if you trade with other Americans also suggest that you’ll be better off if you trade with foreigners who happen to be on the other side of that invisible line.

Comparative advantage drives international trade.

This logic says that we choose to import and export for the same reasons we do business with other Americans: Specializing according to comparative advantage can give us both more stuff. The only thing that’s different about international trade is the scope and scale of specialization that’s possible when there are 8 billion people scattered around the world to trade with.

It leads Americans to export those goods where their opportunity costs are low and to import goods for which their opportunity costs are high. This is why American computer scientists and engineers design the iPhone, while Chinese factory workers manufacture them. And both sides gain when trade is driven by comparative advantage, as this division of labor leads to lower iPhone prices for Americans and better-designed smartphones for the Chinese.

Does comparative advantage really drive international trade?

The price tag will tell you a lot about your comparative advantage.

Some of this might seem a bit far-fetched. After all, do people really make the sort of comparative advantage calculations we outlined in Chapter 8 before deciding whether to import or export goods?

The answer is yes, but in a much simpler way. All you need to do is look at the price tag. When you shop for shirts, the cost-benefit principle tells you to pay careful attention to the price. And in a competitive market, the price is equal to marginal cost. (Yep, that’s the marginal principle at work again.) This means that when you compare the price of an imported shirt with the price of the domestically produced shirt, you’re effectively comparing their marginal costs. The opportunity cost principle reminds you that marginal cost should include all relevant opportunity costs. This means that when you compare the price of domestic versus imported shirts, you’re effectively comparing the opportunity cost of each—and this is exactly what the idea of comparative advantage suggests you should do.

By looking for the lower-priced shirt, you’re effectively evaluating which shirt was made at the lowest opportunity cost. And when you buy that cheaper shirt, you’re buying from the manufacturer who has a comparative advantage in shirt-making.

What Gets Traded?

Comparative advantage yields a pretty stark piece of advice: Produce what you’re good at and buy what you aren’t. Applied to international trade, this says to export the stuff you can produce at the lowest opportunity cost, and import the other stuff. In reality, that advice is a bit too stark, because there’s one more factor to consider: trade costs.

Trade costs determine whether it’s worth buying or selling internationally.

Trade costs are the extra costs—aside from the price—incurred as a result of buying or selling your goods internationally rather than domestically. For instance, buying a car from Japan involves shipping costs. You might also have to pay an extra tax to the U.S. government on imports, or a tax to a foreign government for exports. The opportunity cost principle reminds you to consider the full set of costs—not just the out-of-pocket financial expenses. And so trade costs also include the hassle of working across language barriers, trading across different time zones, dealing with foreign laws, and adapting to different ways of doing business.

The cost-benefit principle says that trade is only worthwhile if the benefit exceeds the cost. This means that you should only import a good if the price you can get it for from another country is sufficiently far below the local price as to offset the associated trade costs. Likewise, you should only export a good if the price you’ll get for it in another country is sufficiently far above your local price as to offset the export-related trade costs.

Trade costs determine how important international trade is in your sector.

It follows that it’s unlikely to ever be worth importing or exporting products with high trade costs. On the flip side, there’s a lot of international trade in products with low trade costs. And so trade costs determine whether international trade is likely to be a big factor in your market.

For example, trade costs associated with digital music are virtually zero—Spotify simply exports bits and bytes—and so there’s a huge amount of international trade in music. Clothes are more expensive to trade, but they’re still easily sent in massive container ships, which explains why your shirt was probably imported. However, it’s prohibitively expensive to get a cavity filled in another country (think of the flight costs), and it’s virtually impossible to transport a house. Consequently there’s almost no international trade in dental services, and no international trade in houses.

Do the Economics

Which of the following goods or services are traded internationally? (Hint: Think about the relevant trade costs.)

- Land

- Coffee beans

- Laptops

- A haircut

- Cars

- Bowling shoes

- Wheat

- A hot cup of coffee

- Cloud computing

- Hair gel

- Bikes

- Bowling alleys

- Flowers

- Sandwiches

- Surveillance equipment

- Hairdressing scissors

- Taxi rides

- An afternoon bowling

Trade costs don’t just determine what is traded. As the next case study shows, they also determine how much is traded. Indeed, declining trade costs are responsible for one of the most important economic trends of your lifetime.

Interpreting the DATA

Global trade is rising because of declining trade costs.

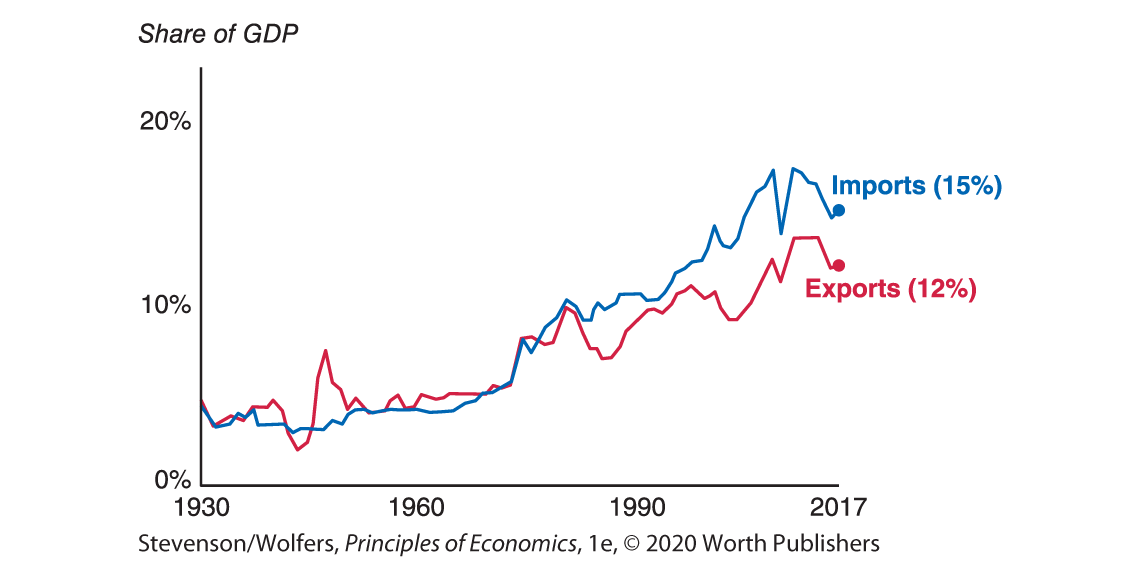

International trade—both exports and imports—has been a growing share of the U.S. economy throughout the entire postwar period (Figure 1). This trend—sometimes called “globalization”—has transformed the economy. And it’s largely due to declining trade costs.

Figure 1 | Imports and Exports Are a Rising Share of the U.S. Economy

Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The United States has brokered trade agreements with a number of countries that have eliminated extra taxes (called tariffs) imposed on trading with them. Some of these trade agreements have also reduced the red tape that often hinders exporters.

The standardization of shipping containers dramatically decreased the cost of shipping goods overseas, and ongoing improvements in air travel reduced transport costs. The increased adoption of English has made international transactions run more smoothly, and an increasingly global business culture makes it easier to do business across borders.

The internet has made global communication much cheaper and quicker, which has fueled greater international trade in services. For instance, the financial industry is becoming more globalized as computers link banks and financial networks at lightning speed. And it’s now easy for foreign radiologists to read X-rays taken in the United States.

She has seen the world.

As trade costs fall, companies trade more intermediate inputs, creating global supply chains. For instance, Barbie is produced by a global supply chain. Her plastic limbs and hair are made by workers in Taiwan and Japan; she’s assembled in Indonesia, Malaysia, and China; and she was designed and marketed in the United States. International trade allows Barbie to be manufactured and sold more inexpensively, while allowing workers in each country to contribute what they do best.

Choosing Your Trading Partners: Sources of Comparative Advantage

It’s a good bet that trade costs will continue to fall, making international trade an even more important force through your career. This more integrated global marketplace will create new opportunities for you to exploit your comparative advantage. Which raises the question: What is your comparative advantage, and what strategic choices can you make to enhance it?

Economists have identified three factors that shape your comparative advantage: relatively abundant inputs, specialized skills, and the benefits of mass production. Let’s examine each in detail.

Source one: Abundant inputs—Take advantage of what you have, to get what you want.

New Zealand has lots of land, and so New Zealand farmers can raise sheep cheaply to export wool. Canada has ample forests, and so Canadian foresters export wood and related products like paper. Saudi Arabia has abundant oil, which is an essential input into the gasoline that Saudi refineries export. France has ideal soil for growing grapes, leading French winemakers to export wine. The United States has thousands of scientists, and so pharmaceutical companies export new medicines. Each of these examples reflects a comparative advantage that is due to the relative abundance of the necessary inputs compared to their trading partners.

Some of this relative abundance of inputs is simply a matter of climate, geography, and natural resources. But people, businesses, and countries can shape their advantages through strategic investments. For instance, America’s colleges and universities have helped create the relative abundance of highly educated workers that led to the United States’ comparative advantage in scientific fields.

This focus on abundant inputs suggests that international trade is all about exporting products made with resources you have a lot of, and importing products made with resources that are scarce. Importantly, it is relative abundance of inputs that matters—whether you have more or less labor relative to capital, land, or sunshine than your trading partners.

The more your trading partner differs from you, the larger the gains from trade will be. If your trading partner has very different resources—whether they’re worker skills, machinery, natural resources, or climate—it’s likely they’ll also have very different opportunity costs, leading to gains from trade.

Interpreting the DATA

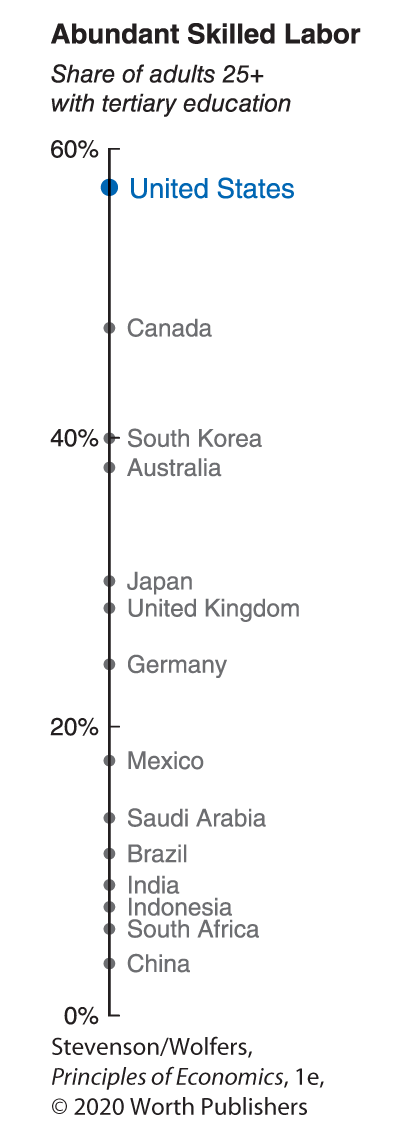

What inputs are relatively abundant in the United States?

As a savvy manager, you should specialize in making and exporting products that rely on inputs that are relatively abundant near you. And you’ll find likely customers in areas where those inputs are relatively scarce. On the flip side, you should import those goods that require inputs that are relatively scarce near you. And you’ll typically get the best deal if you import them from a country where those inputs are relatively abundant.

So which inputs are abundant, and which are scarce in the United States relative to other countries? Compared to countries like Australia and Canada, the United States doesn’t have particularly abundant land (Canada is physically bigger than the United States, but its population is smaller than that of California!). And compared to countries such as China, India, and Brazil, the United States doesn’t have particularly abundant labor. This might leave you thinking that because our businesses use state-of-the-art machinery, the United States has relatively abundant capital. But studies have found that the United States exports goods that are slightly less capital intensive than its imports. So what abundant inputs drive our comparative advantage?

Data from: World Bank.

The answer is a specific category of labor: highly educated workers. The United States has a much higher share of workers with some college education compared to other countries. In turn, this means that our comparative advantage is in producing skill-intensive goods, such as scientific and medical instruments, airplanes, and computer software. This is good news for smart college students: You’re our comparative advantage!

By contrast, because less-educated workers are relatively scarce in the United States, we have a comparative disadvantage in mass manufacturing. This explains why Americans import toys, footwear, and clothing from Chinese and Mexican businesses with easy access to plentiful less-educated, low-wage workers.

So when you think about your comparative advantage, just look around at your classmates and realize that relative to your international competitors, you have access to a large number of highly educated and creative workers.

Source two: Develop a specialized skill.

Businesses in Switzerland, France, and the United States have roughly similar access to capital and skilled labor. Yet the Swiss are the world’s best watchmakers, the French produce the greatest cheese (sorry, Wisconsin!), and Americans make terrific movies (usually). In each case, skilled artisans produce watches, cheese, or movies in a way that their foreign counterparts can’t match. Your unique skills, production methods, or expertise can be an important source of comparative advantage.

As they say, practice makes perfect: If you—or a country or a business—focus on a particular product for a long time, you’ll likely discover new production techniques that lower your costs. This comparative advantage gets stronger over time, as you produce more and learn more. Economists refer to this as “learning by doing,” and it explains how a long-term investment in a specific industry can pay off. As a manager, you’ll discover that the more you produce, the more efficient you’ll become, which will lead you to sell and hence produce more, creating more opportunities to learn, further reinforcing your comparative advantage.

Source three: Exploit the benefits of mass production.

Ikea sells millions of Billy bookcases each year to buyers all around the world. It sells so many of them because the Billy bookcase is so cheap. And the Billy bookcase is so cheap because Ikea sells so many of them. This virtuous cycle arises because of the benefits of mass production (which are sometimes called economies of scale).

Billy the bookcase and his creator, Ronnie the robot.

When you’re producing millions of bookcases, you can invest in creating incredibly specialized production lines that are much more efficient. For instance, rather than hiring skilled woodworkers to make the Billy, Ikea has programmed specialized robots to do most of the work, and they can work 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. The automated production line is so efficient that it makes a new bookcase every five seconds. In addition, Ikea produces so much furniture that it’s one of the world’s largest purchasers of wood. This gives it substantial bargaining power, which it uses to demand cheaper wood, further lowering its input costs. Put it all together, and the opportunity cost of producing another bookcase is lower for Ikea than for any other business. These lower opportunity costs due to the benefits of mass production can be another enduring source of comparative advantage, particularly for large producers.

EVERYDAY Economics

Using comparative advantage at home

The same big idea that drives international trade—comparative advantage—also explains why you trade tasks with your roommates to make your household run more efficiently. It’s simple: You want to allocate each task to the person who has a comparative advantage. And thinking about the sources of comparative advantage can help.

Who should do the weekly shopping? The idea that abundant inputs creates comparative advantage suggests that you should assign that task to the housemate who owns a car, because they have a relative abundance of the necessary capital equipment. Who should be responsible for IT around the house—making sure the Wi-Fi works, and that the stereo can pair with everyone’s phones? Assign that task to whoever has developed a specialized skill in computer networking. As they get used to troubleshooting, they’ll develop even more expertise. And what about cooking dinner? Anyone can cook spaghetti, so perhaps anyone could have a comparative advantage here. True, but since it’s just as easy to make spaghetti for four as it is for one, the benefits of mass production create a comparative advantage for whoever is already cooking for themselves to cook for the whole household. The same ideas that guide successful global businesses can also guide your household. Allocating tasks according to comparative advantage will make your household more efficient, and it’ll make sure you get your shopping, technology, and meals dealt with at the lowest possible opportunity cost.

Now that we’ve explored how comparative advantage drives international trade, it’s time to explore how international trade reshapes supply and demand.

Land

Land