9.4 International Trade Policy

Your company’s success in winning international business will depend on navigating the complex maze of government policies that foreign governments put in place to help protect their domestic businesses—your rivals!—from competition. So it’s time to explore how countries regulate trade and how those regulations will affect your market conditions. We’ll then turn to examining global trade agreements, which limit the ways that individual countries can protect their businesses.

Tools of Trade Policy

Managers of international businesses quickly learn that they need to compete in two domains. The first is the market, where you’ll compete to produce the best goods at the lowest price. And second, you’ll be forced to compete in the political marketplace, as your foreign rivals will lobby their governments to adopt policies that will protect them from having to compete with you. That’s why our next task is to evaluate how international trade policies can affect your market.

Tariffs are a tax on imported goods.

As tariffs are taxes on imported goods, they increase their trade costs. We can use our domestic demand and supply curves to figure out the consequences of this higher trade cost.

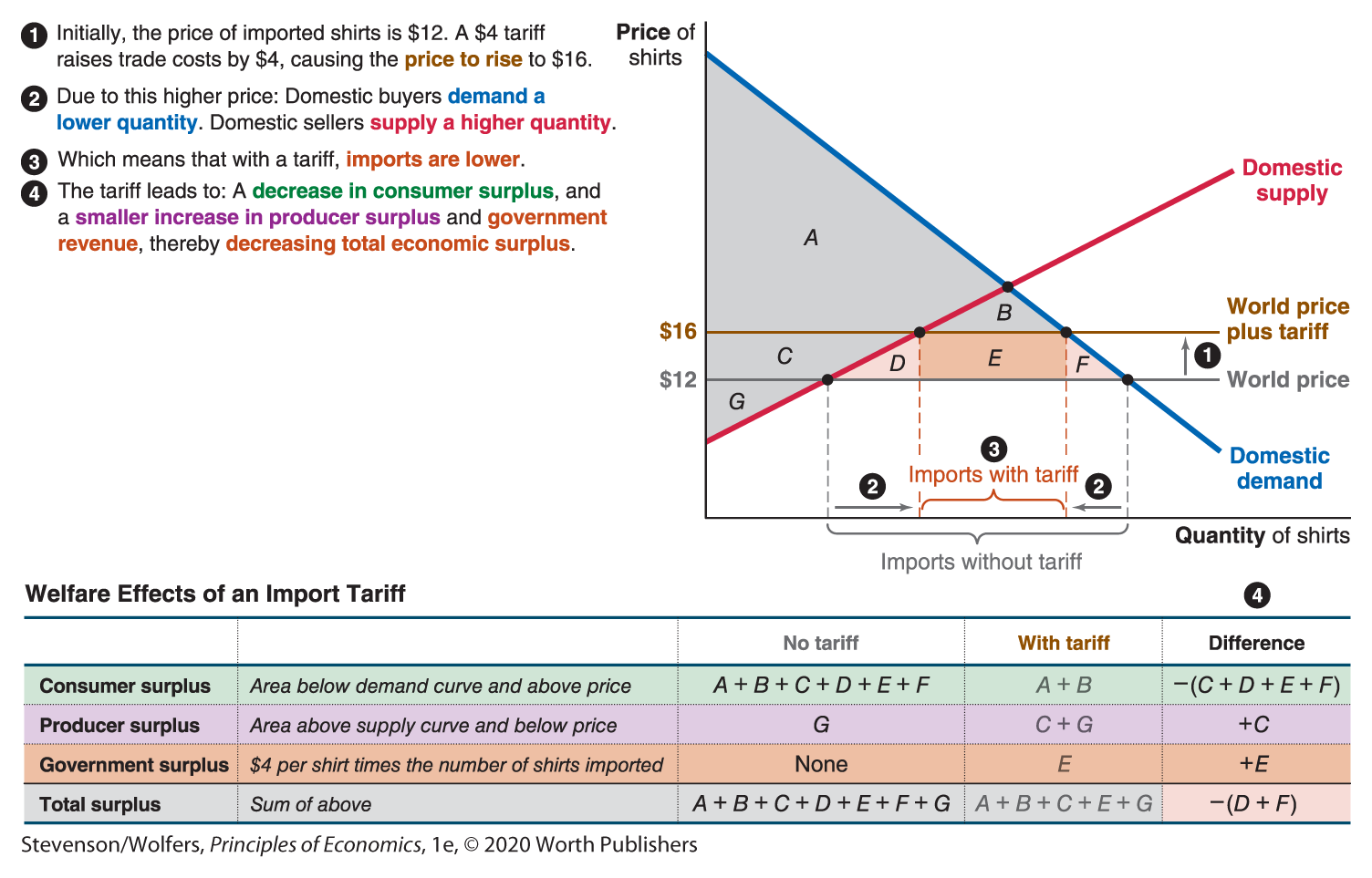

For instance, what happens if the government imposes a $4 tariff on shirts? We already know what happens without the tariff: The equilibrium price will be equal to the world price of $12. This outcome is shown in gray in Figure 9.

Figure 9 | The Effects of an Import Tariff

Let’s use our three-step recipe to see the effects of adding a $4 tariff:

- Step one: What will the new price be? This tariff adds $4 to the trade costs of importers. Because the world price of $12 is fixed, importers have to pay the world price of $12 plus the tariff of $4. Therefore, the price of shirts rises by $4, to $16.

- Step two: At this new price, what quantities will be demanded and supplied? Consult the domestic supply and demand curves to discover that at the new higher price, the quantity demanded by domestic buyers is lower, while the quantity supplied by domestic suppliers is higher.

- Step three: What quantity will be traded? Recall that imports make up the gap between the quantities demanded and supplied. Because this gap shrinks, imports fall.

OK, so given these effects, who wins and who loses from a tariff?

Domestic buyers are unhappy because the higher price means they either pay an extra $4 per shirt or buy fewer shirts. Their consumer surplus is the area under the demand curve and above the price. Before the tariff, this was equal to the triangle made up of the areas A + B + C + D + E + F. After the tariff, this falls to area A + B. Thus, tariffs cause consumer surplus to fall by area C + D + E + F.

Domestic suppliers are happy because the higher price means higher profit margins on each shirt sold and they also sell an increased quantity. Producer surplus is the area above the supply curve and below the price. Without a tariff, this was area G. After the tariff, it is area C + G. Thus, tariffs cause producer surplus to rise by an amount equal to area C.

The government also gains because it collects $4 of revenue for each shirt imported. This total tax revenue is equal to the $4 tax (which is the height of rectangle E) times the total number of imports (the width of rectangle E). So the tariff yields tax revenue equal to the height times width—that is, the area of rectangle E.

Adding all this up, consumers lose C + D + E + F; producers gain C; and the government gains E. Hence, in total, a tariff will decrease the economic surplus of Americans by an amount equal to area D + F.

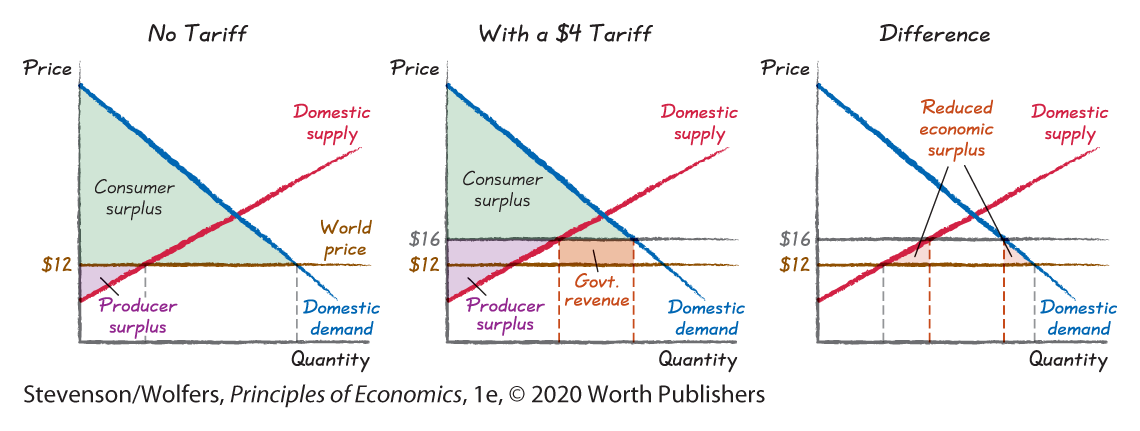

If you’re worried that Figure 9 looks complicated, don’t be. It’s really not so bad. The charts below show how we built this figure. We started by analyzing outcomes without a tariff. Then we analyzed the case with a tariff, tracking consumer surplus, producer surplus, and government revenue. Finally, we looked to see what changed.

And the end result is worth all this work. We’ve found that taxing goods made in other countries actually reduces the total economic surplus of Americans! If this is surprising, here’s the intuition: The extra government revenue isn’t really a gain, because it’s effectively paid by American consumers who now pay an extra $4 for each shirt they import. And so the tariff shifts money from one set of Americans (consumers) to another (the government). The tariff also raises the price of shirts, which distorts both the choices that consumers make (they’ll buy fewer shirts) and the choices that producers make (they keep producing even when it’s not efficient to do so).

Red tape is like a tariff because it raises costs, but it doesn’t even raise revenue.

Given all the red tape, it’s a miracle this bicycle ever made it to Burundi!

Tariffs aren’t the only tool that governments use to reduce international trade. Consider what it takes to export a bicycle to Bujumbura, a city in Burundi where bikes are often used as taxis. Even once you’ve shipped that bike to the nearest port in Tanzania, it has to wait for 50 days of pre-arrival approvals, 8 days of port handling, 15 days to go through customs, and then a month on a train. Once the bike arrives at the border of Burundi, it then takes another 12 days to get through customs again, be loaded on a barge, and then go through customs again at Bujumbura port. The 124 days, 19 documents, and 55 signatures required to get a bike to Bujumbura aren’t just a headache; they add a lot to your trading costs.

All this red tape ultimately has the same effect as a tariff—it increases trade costs and so raises the price of American-made bikes. The effects of this higher price is the same, whether it’s caused by tariffs or red tape: It reduces the quantity demanded, raises the quantity supplied by domestic sellers, and therefore reduces international trade. But red tape is more inefficient than a tariff, because it doesn’t even raise revenue for the government.

Import quotas have similar effects to tariffs, but don’t raise revenue.

Tariffs and red tape affect trade because they raise the price of foreign goods, reducing the quantity of international trade. However, setting an import quota would also have the same impact. An import quota limits the quantity of a good that can be imported. For instance, the $4 tariff on shirts in Figure 9 reduces imports to a quantity equal to the width of rectangle E. The government could achieve the exact same outcome—the same price and the same quantity demanded, supplied, and imported—if instead it imposed a quota limiting imports to this number. However with a quota, the government wouldn’t raise revenue the way it does with tariffs (unless it auctioned off the scarce import licenses).

Exchange rate manipulation changes the price of your goods in foreign markets.

Foreign governments also can give their companies a leg up by manipulating their exchange rate. Think about how this affects an American exporter, such as Boeing. If a Boeing 737 typically sells for US$60 million (the “US$” symbol means “in U.S. dollars”), and it takes six Chinese yuan (China’s currency) to buy one U.S. dollar, then each plane will cost a Chinese buyer 360 million yuan. But if the Chinese government sets the exchange rate so that it takes seven yuan to buy one U.S. dollar, then the price of Boeing’s plane for a Chinese buyer rises to

The lower yuan also makes it cheaper for Americans to import goods from China. Consider a shirt that a Chinese business will sell for 84 yuan. When the exchange rate is 6 yuan per dollar, this sells for

Current Trade Policy

We’ve come a long way in understanding the many ways that government policy can shape trade. Let’s take a look at the current state of play.

U.S. trade policy largely embraces free trade.

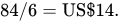

While trade policy is still hotly debated—particularly since the election of President Donald Trump—the United States still broadly encourages international trade. As shown in Figure 10, the average tariff charged on imports into the United States was only 1.9% in 2018, which is down from rates as high as 29% over a century ago. The United States has as few or fewer trade barriers than nearly all of our trading partners.

Figure 10 | Average Tariff Rate Levied by the United States

Data from: U.S. International Trade Commission.

However, the United States protects a few specific industries from foreign trade. Most notably, the farm lobby has been very successful in persuading the government to maintain high tariffs, particularly on dairy products, tobacco, and sugar. President Trump also imposed new tariffs on steel and other products. When government economists analyzed all significant import restrictions in 2017, they found that in total they reduce total economic surplus by about $3.3 billion, which sounds like a lot, until you realize that it amounts to about $10 per person.

Bottom line: The United States has largely embraced free trade. That conclusion holds even as the future is less clear, as President Trump has argued both for aggressively increasing tariffs, and for eliminating them altogether.

The United States has signed many free-trade agreements.

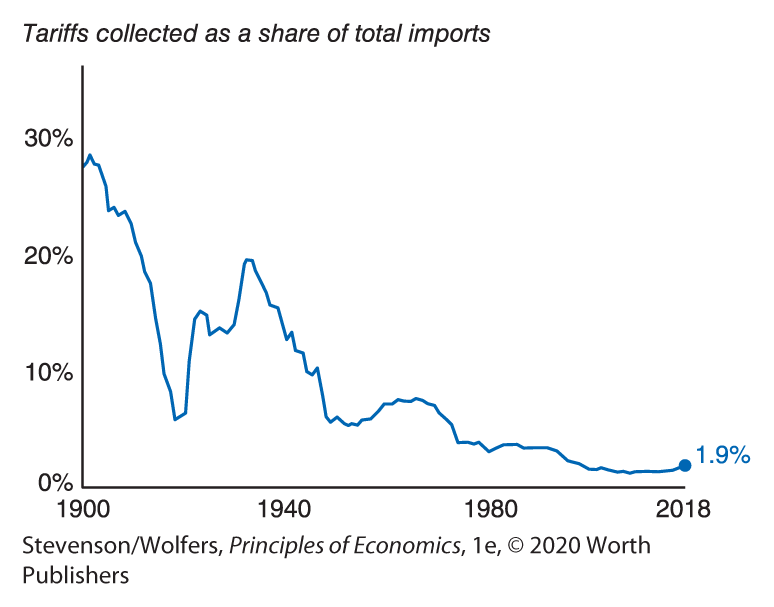

Your fate as an exporter will depend partly on the trade policies adopted by the countries you’re exporting to. Tariffs vary across products and across countries. The average tariff rates in the world’s major economies, shown in Figure 11, are typically pretty low.

Figure 11 | Average Tariff Rate

Data from: World Bank.

In many cases, you’ll actually face lower tariffs than shown here, because the United States has negotiated free-trade agreements with various neighbors. The most important agreement is NAFTA—the North American Free Trade Agreement—which includes Canada and Mexico. A new agreement called the USMCA may replace NAFTA if the three countries approve the replacement, but the new agreement will essentially continue the long-standing free trade arrangements. The United States is also a member of the Dominican Republic–Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), which includes Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua. The United States has also negotiated bilateral (that is, two-way) trade deals with Israel, Jordan, Singapore, Chile, Australia, Morocco, Bahrain, Colombia, Panama, and South Korea. While these are often called “free-trade agreements,” it is more accurate to call them free-er trade agreements, since they typically reduce rather than eliminate trade barriers.

The World Trade Organization is a forum for global agreements to reduce trade barriers.

Negotiating these trade agreements country by country is time-consuming. That’s why large-scale multilateral (that is, many-country) trade agreements often make more sense. Today, nearly all countries are members of the World Trade Organization—or WTO, for short. The WTO provides a forum for these countries to jointly agree to reduce or eliminate trade barriers. It has played a major role in reducing trade barriers throughout the world.

WTO agreements also curtail the extent to which individual countries can put up trade barriers. They include two important principles. The first, called most-favored-nation status, means that all member nations must treat all others equally—at least as well as the most favored nation. (There is an exception for free-trade agreements.) And second, the national treatment principle means that imported goods and locally produced goods must be treated equally once they’ve entered a country. If your business is hurt by trade barriers that violate these principles, there may be a useful remedy.

Talks to further reduce trade barriers have been underway since the “Doha round”—named for the Middle Eastern city in which member countries agreed to another round of negotiations. These talks aimed to reduce tariffs on manufactured goods in many poor countries, in return for reduced farm subsidies in the United States and Europe. Unfortunately, the Doha round has remained deadlocked for many years. (Yawn.) But even if this round is a failure, past reductions in trade barriers have unleashed a torrent of international trade whose effects are felt throughout the world. Let’s now turn to analyzing how these international linkages shape your life.