12.1 Labor Demand: What Employers Want

Let’s start by considering how labor demand—that is, what employers want—shapes your wage. The key insight from our study of labor demand is that your productivity plays a central role in determining how much your boss is willing to pay you. Specifically, recall that an employer’s demand for workers is determined by the value of what each worker can produce, which is why savvy executives hire workers until the marginal revenue product is equal to the market wage. It follows that if you want to be offered a high wage, you need potential employers to believe that you’ll produce a lot of valuable output. And so in this section we’ll analyze what makes some workers more productive than others and what employers look for to determine which workers are likely to be most productive.

Human Capital

You’re probably in college because you expect to earn more as a college graduate. In fact, you may even be taking this course because you’ve heard that economics students earn more than other college graduates. I’ve got good news for you: Both are true. Over the course of a lifetime, the average worker with a college degree will earn a million dollars more than those who stop their education at high school. And economics majors will earn even more.

Education makes you more productive.

Economists refer to your accumulated productive skills as your stock of human capital. Because greater human capital can raise your productivity, workers with more human capital tend to get paid more.

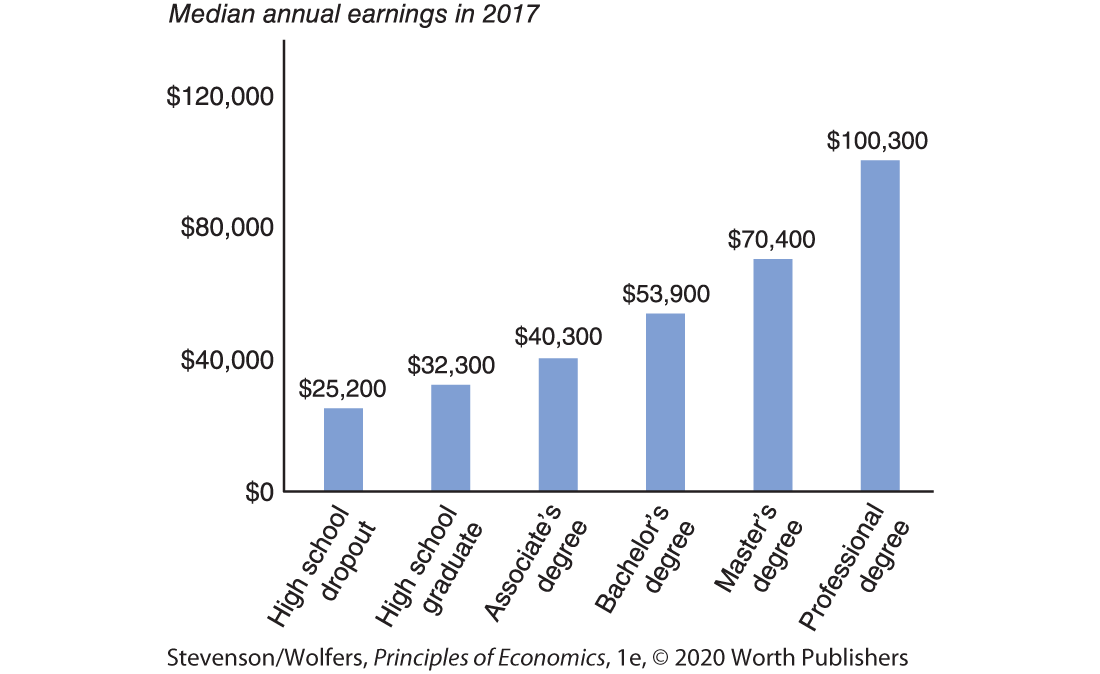

Figure 1 | Education and Earnings

Data from: U.S. Census Bureau.

Indeed, Figure 1 shows median annual earnings among people with different levels of education. (The median means that half the people with that level of education earn at least this much.) The median person with a professional degree, such as a doctor or lawyer, earns roughly twice as much as the median person with only a Bachelor’s degree. And the median person with only a Bachelor’s degree earns roughly twice as much as the median person who drops out of high school before graduating. These differences should make you feel pretty good about the payoff from your current studies. In fact, the typical person’s wages will be higher for each additional year they invest in building their human capital by going to school.

EVERYDAY Economics

Does going to college really matter?

Some people see these income differences by education and say: “Okay, college graduates earn more than high school graduates. So what? Couldn’t this just be because smart people are more likely to go to college? Maybe they would have earned just as much if they didn’t go to college.” They’re asking: Does more education cause higher wages, or is some other factor—such as your innate intelligence or family upbringing—responsible for both higher earnings and more education?

Economists have conducted careful studies to try to sort this out. Comparisons of people with similar IQ scores show that people who went to college earned more than similar people who didn’t. Comparisons of identical twins—who share the same genes and were brought up in the same home—yield the same conclusion. Also, people who grew up near a college—and hence were more likely to attend college—earn more than otherwise-similar folks who grew up farther away from a college and were less likely to attend. All of this suggests: Yes, going to college really does make a difference. A big one.

Education can also serve as a signal of your ability.

A college diploma is a valuable signal.

Why does more education lead to a higher salary? So far we’ve suggested that education makes you more productive, and when you’re more productive, you earn more. Most economists agree that education raises people’s productivity and that’s a big part of why you’ll likely earn more than the typical person who gets less education than you. But it turns out that education plays another role as well. Beyond teaching you useful skills, your degree conveys information—that is, it signals—to your employer that you are a good worker.

Here’s the idea. Employers value smart and tenacious workers. But in an interview, employers can’t easily figure out who actually has these characteristics and who’s just saying they do. And so savvy employers look at your past achievements that might convey this information—such as your education. By this view, the fact that your degree requires hard work means that only folks with both brains and tenacity will find it worth it to complete a college degree. (Applying the cost-benefit principle, the cost to those who are less tenacious is just too high.) And so employers looking for smart and tenacious workers realize they should hire college graduates.

But the reason they do this isn’t necessarily that they value any specific skills you learned in college. Instead, it’s because you did something that many other people would find too challenging, and this conveys otherwise unobservable information about how productive you will be.

The idea is that actions speak louder than words—you can’t simply tell a potential employer how hard-working and tenacious you are, because anyone might claim that in an interview. Education serves as a signal—a costly action that you take to credibly convey information that would otherwise be hard for someone else, like a potential employer, to verify. A useful signal helps employers figure out which workers are likely to be more productive. However, for education to work as a signal, it must be substantially costlier for less productive workers to earn a college degree than it is for highly productive workers. It’s precisely the fact that college is hard—and even harder if you aren’t tenacious and hard-working—that makes it serve as a useful signal.

EVERYDAY Economics

Which interests should you tell employers about?

What do your hobbies signal about you?

During job interviews, potential employers often ask: What do you like to do in your free time? This isn’t just a question to break the ice; your answers can signal otherwise unobservable traits about you. So which interests and hobbies should you mention? Try to focus on the ones that illustrate relevant traits for the job. If you spend a lot of time helping your parents by looking after younger siblings, say so: It signals that you are a team-player and responsible. If you spend time tutoring others, mention it so employers know that you are likely to be helpful to your colleagues. If you’ve run a marathon, tell employers because it shows that you are persistent and disciplined. Enjoy sky diving? Be careful: That might signal that you are fearless, which is a good attribute if you’re applying to the military, but a bad one if you’re applying to work in child care.

Does education raise your productivity or signal your ability?

Economists often present the ideas of signaling and human capital as two competing ideas to explain why more education leads to higher wages. In reality both ideas have some validity. Take signaling: As an employer you’ll want to use the information you have about people to try to choose who’s likely to be the most productive worker. College is a useful signal, because college grads have different traits on average than those without college degrees (beyond what they’ve learned in school). For instance, people who are better able to delay gratification are more likely to go to college. And workers who are able to delay gratification are valuable employees, because they’ll endure short-run costs—such as working through dinner—for long-run benefits, such as finalizing a big project on time. But human capital is also important. Employers understand that while you’re in college you’re building your writing, quantitative, and reasoning skills. They value this and will pay you a higher wage because this human capital makes you a better communicator, problem solver, and strategic thinker on the job.

Efficiency Wages

So far we’ve seen that employers pay more to workers who are more productive. But sometimes employers pay workers more to make them more productive. Let me explain. You’re a smart, educated person capable of being really productive at your job. But you also get tired, enjoy snacks, and wonder what your friends are doing on social media. Most people find it hard to stay focused on the job all the time. If you follow the marginal principle, you’ll ask yourself whether it’s worth working hard for one more hour. The opportunity cost principle reminds you that the alternative is slacking off. And the cost-benefit principle says that it’s worth slacking off in that hour when the marginal benefit of working hard is less than the marginal cost of that effort. And so if the marginal cost of effort exceeds the marginal benefit, perhaps you’ll slack off.

A higher wage provides an incentive to keep working hard.

Your boss understands this, which is why in many factory jobs employers closely monitor what their workers are doing. But if your boss can’t monitor your effort closely, they might try a different strategy, tweaking your costs and benefits to keep you working hard. So when no one is watching, how does your employer ensure that you keep your nose to the grindstone? By paying you a wage that’s higher than what you could earn elsewhere. They figure that the higher your wage, the more you value your job. (As the opportunity cost principle highlights, how much you value your job depends on how much you’re paid, relative to your next best alternative.) And the more you value your job, the less you’ll want to risk losing it by slacking off. Highly paid workers are also more likely to feel valued, inspiring them to give back in the form of greater effort.

Indeed, some employers have calculated that a higher wage might inspire you to work so much harder that your higher wage pays for itself. Economists refer to this as an efficiency wage—a higher wage paid to encourage greater worker productivity, by increasing worker effort and reducing worker turnover.

Some jobs pay more because effort is costlier to monitor.

What this means is that jobs where it’s hard for your employer to monitor your effort will tend to pay a bit more. That’s one reason that nannies tend to make more than day-care workers. Parents can’t monitor nannies as well as managers at day-care centers do. As a result, many parents pay an efficiency wage, while few day-care centers do.

The Market for Superstars

Human capital, signaling, and efficiency wages can’t fully explain why Beyoncé earned $105 million in 2017. That’s over 2,000 times more than the median singer or musician. Is she 2,000 times more talented? Beyoncé is good, but maybe not that much better.

When millions of people can enjoy your talents at the same time, small differences in talent can have big effects. Before I explain why, I want you to think of the song you most want to hear right now. Okay, who sings it? Is it a superstar with millions of fans or a local singer in your community? Indie music lovers aside, most people answer that they want to listen to a song by a superstar. After all, there’s no point listening to the 100th best musician when you can listen to the best.

Technology expands the reach of superstars.

The existence of superstars like Beyoncé reflects the combination of two facts—that people like to hear the best, and technology makes it easy for the best to reach millions of customers. To see why this matters, look back to the music scene a century ago, when most music was consumed by listening to live concerts. There were hundreds of musicians who would each make a living by filling the biggest concert hall in their town. The reach of the very best musician was limited by the size of the available concert halls. As a result, there wasn’t much of a difference in pay between the best musician and the 100th best—both would sell out their local venues. Now fast-forward to the modern era of recorded music and online streaming. Today’s top stars have a far greater reach. Beyoncé, for instance, has sold over 35 million albums and her songs have been streamed billions of times. When you can listen to the world’s best singer, there’s no longer much reason for anyone to listen to the 100th best.

Beyoncé’s career illustrates that whenever you can reach millions of customers—each of whom has a slight preference for the very best—the labor market becomes something of a winner-take-all market. In such a market, the very best performers capture a large share—sometimes all—of the rewards, leaving little for those who are just slightly less skilled. Occupations that demonstrate this winner-take-all dynamic include actors, authors, and athletes. In these markets, each person competes to be the next global sensation. Pursuing a career in these fields can be very lucrative but very risky, because only a handful of people make it to the very top.

Interpreting the DATA

Why is chief executive pay so high?

Mary Barra, the CEO of General Motors, earns millions of dollars each year.

If you were on the board of a major corporation, how much would you be willing to pay to get the very best talent to run the company? Before you answer, I’ll share with you the results of a recent study, which estimated that getting the very best chief executive will raise the value of your company by 0.016% more than the 250th best alternative. That doesn’t sound like much. But if your corporation is General Motors, which is worth roughly $50 billion, then even this very small difference is worth an extra $8 million. That’s a key reason big firms are willing to pay millions of dollars to get the very best managers.

There’s an important idea here: The more broadly you can spread your talent—say, across a big firm or a big market—the more likely it is that being slightly better than the competition will be enough to generate a multimillion-dollar pay deal.