13.3 Social Insurance, the Social Safety Net, and Redistributive Taxation

The numbers you have seen so far are data on people’s incomes before taxes. Once we take taxes and transfers—meaning the cash, goods, and services the government provides some people—into account, there is less inequality and less poverty. That’s because most governments take actions that help reduce the inequality and poverty that would occur without government.

There are several ways in which government reduces inequality and poverty. Government funds the social safety net, which is the cash assistance, goods, and services provided by the government to better the lives of those at the bottom of the income distribution. Part of the safety net are government programs that insure you against bad outcomes such as unemployment, illness, disability, or outliving your savings. These programs are called social insurance because it’s insurance, but it’s provided socially by everyone in society rather than by a private insurance company. Government raises the money for the safety net (and everything else it does!) through taxes—which themselves are an equalizing force, since our overall system of taxation is progressive. A progressive tax system is one in which those with more income tend to pay a higher share of their income in taxes.

Let’s explore how the safety net, social insurance, and taxes equalize incomes in the United States.

The Social Safety Net

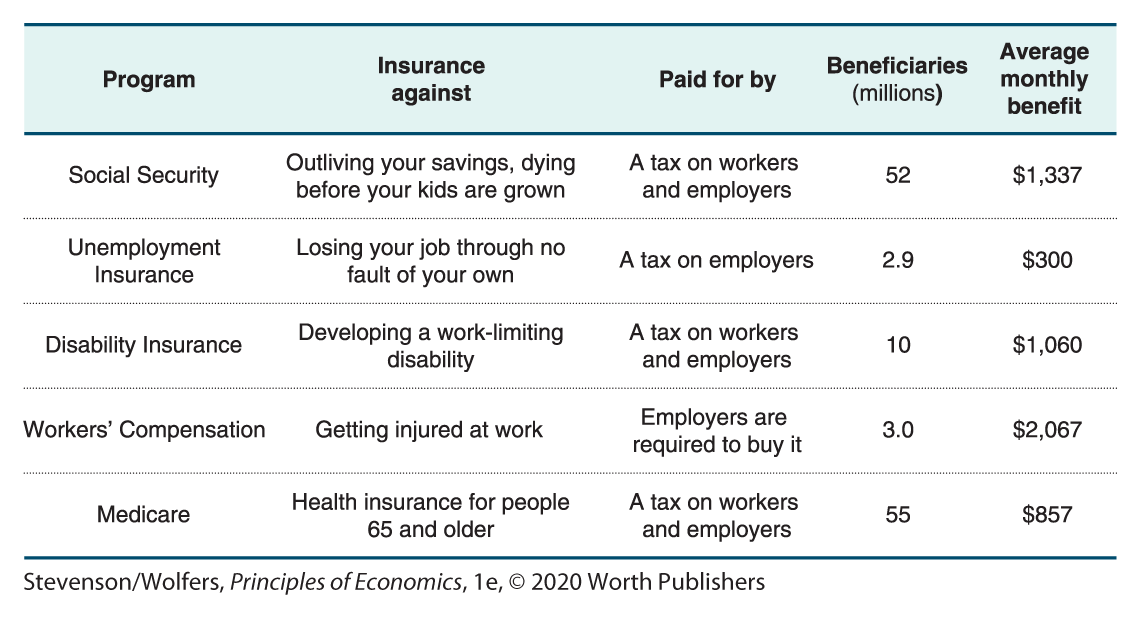

To help ensure a minimum material standard of living for those at the bottom of the income distribution, the government does more explicit redistribution to those at the bottom through social safety-net programs. The major programs are described in Figure 11.

Figure 11 | Major U.S. Government Redistribution Programs

Data on recipients and costs are from 2014-2015. Programs are listed in order of total expenditures.

Let’s now analyze the main features of the U.S. social safety net.

The safety net is means-tested.

In order to ensure that benefits only reach the truly needy, social safety net programs are means-tested, which means that your eligibility depends on your income. In addition, some programs also have asset tests to ensure that the idle wealthy don’t get benefits.

The elderly and the disabled are protected by Supplemental Security Income; working families are helped by the Earned Income Tax Credit; single parents often rely on welfare, and many of the jobless get by with the help of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (lots of people still refer to it as “food stamps”). Medicaid helps each of these groups. In theory many of those in poverty qualify for housing assistance, but in reality long waiting lists mean that few actually receive it.

This patchwork of programs means that some people fall through the cracks and don’t receive any assistance, while others are eligible for several programs.

The safety net helps support a lot of families.

Once we account for the overlap across programs, somewhere between one-in-three and one-in-four people live in a household currently receiving some form of assistance. An even larger proportion will need this assistance at some point in their lives. Thus, the social safety net provides support for much of the population. This may surprise you if you have never received benefits or you think you don’t know anyone who has. But perhaps this is because many people perceive there to be a stigma in relying on the safety net, and so they don’t tell friends or family about it.

The safety net provides minimal support.

Notice that the typical monthly payments in Figure 11 aren’t particularly generous. But these safety net programs often provide enough to raise low-income families with children above the poverty line. Recall that the poverty rate is calculated excluding most of these benefits—direct cash assistance like welfare and Supplement Security Income is included, but the other benefits are not. Including the value of all benefits helps lift about a third of the people living in poverty above the poverty line.

The safety net includes cash assistance, tax breaks, and in-kind transfers.

While some safety net programs provide income or tax breaks, others provide specific goods, which are sometimes called in-kind transfers. For instance, the food support program known as SNAP provides an ATM-style card that can only be used to buy food; housing vouchers can only be spent on housing. But many economists are puzzled by this: Why help people with in-kind benefits, rather than just giving an equivalent benefit as cash? After all, recipients can use cash to buy whatever they most need—food or housing.

There are four key reasons why government provides in-kind benefits rather than cash benefits. First, giving goods rather than cash prevents recipients from making bad choices, such as gambling the money away. Second, taxpayers may care more about reducing homelessness or hunger, rather than about what will make the recipient happiest. Third, providing an in-kind benefit that only the poor will value—such as public housing—makes it more likely that only those who truly need the assistance will get it. And fourth, some in-kind benefits—such as child care—are a complement to work, which helps offset the incentive for recipients to rely on the safety net rather than work.

EVERYDAY Economics

Why parents give gifts rather than cash

When it comes to birthdays, many parents are a bit like governments, preferring to give gifts rather than cash, despite the fact you could use cash to buy the perfect gift. They do so for similar reasons. Perhaps your parents are worried that you’ll make bad choices, spending cash on parties rather than a new warm coat. Or maybe they care more about your success than your happiness. Also, parents understand complements and often give “responsible” gifts to help you succeed—such as an interview suit or a laptop. After all, your success means that you won’t need to rely on them for support when you are older.

Social Insurance Programs

Don’t worry. It’s insured.

Some safety net programs are not means-tested, because they are insurance programs designed to cover everyone—the rich and the poor. You probably know about renters insurance, homeowners insurance, and car insurance: You pay a small amount each month to the insurance company, and if misfortune strikes, your stolen laptop will be replaced, your burnt home will be rebuilt, or your crumpled car will be fixed. Buying insurance is a good way of protecting yourself against these risks. The same logic says that it’s also a good idea to insure against the financial risks involved with losing your job, becoming disabled, incurring huge medical bills, or outliving your savings. The problem is that many of the things we want to insure against are difficult for private insurance companies to provide profitably (for more on why see Chapter 20).

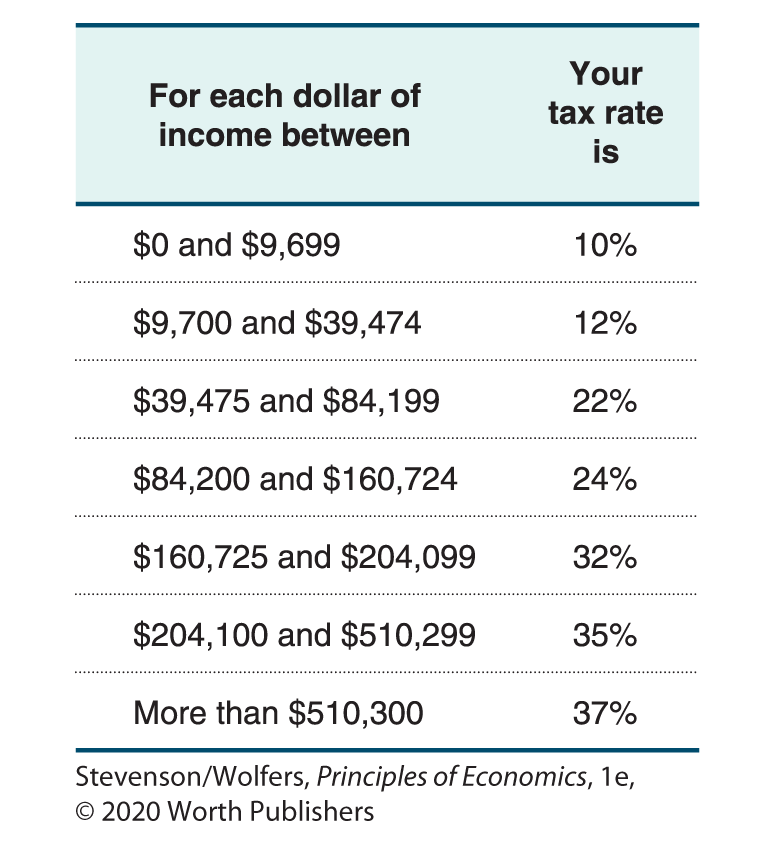

Because of failures in the private insurance market the government steps in to make sure that everyone can get access to certain forms of insurance. It is known as “social” insurance because it is provided “socially”—by your fellow taxpayers—rather than by private insurance firms. Figure 12 outlines the most important social insurance programs in the United States.

Figure 12 | The Largest U.S. Social Insurance Programs

Note: The average benefit amount for workers’ compensation is the amount spent by employers on total benefits divided by the number of claims in 2015.

Benefits are based on certain bad outcomes.

Social insurance—like private insurance—pays you when you experience a bad outcome. Unemployment insurance exists to provide protection against temporary spells of unemployment. Workers’ compensation provides payments and medical benefits if you are injured at work. And disability insurance provides payments if you develop a work-limiting disability. Social Security provides income in retirement and therefore insures people against outliving their savings. The “bad” outcome is living longer than you expect or having inadequate savings due to stock market declines or higher than expected inflation (which means your money doesn’t buy as many things as you were expecting). Social Security provides a stream of income to the elderly for the rest of their lives to ensure that they don’t outlive their savings. Social Security also provides benefits to certain survivors when people die. When someone loses a parent growing up, they receive Social Security benefits to help support them until they turn 18. In this way, Social Security also provides life insurance to parents. Finally, Medicare provides health insurance to people age 65 or older and therefore covers some of the costs of medical care when they develop health problems.

People pay into social insurance programs.

Just like you pay your insurance company a monthly payment to provide you with car insurance, people make regular payments into social insurance programs. Sometimes the money is withheld from workers’ paychecks and sometimes employers pay. For example, for Social Security, disability insurance, and Medicare you pay 7.65% of your wages to the program, and your employer also kicks in the same amount. Employers pay employment insurance taxes on workers’ wages and are asked to pay a certain amount per worker to ensure that their workers are covered by workers’ compensation insurance.

EVERYDAY Economics

Insuring against bad decisions?

Social Security insures us against outliving our savings; in that way it also insures us against the possibility of making bad decisions about retirement. People who aren’t good planners will spend their income having fun today, rather than saving for old age. They only discover what a bad idea this is when they find themselves old, and in poverty. Fortunately, Social Security insures against the risk of making such myopic decisions, ensuring that you’ll have enough to get by, and hopefully avoid poverty. But Social Security doesn’t guarantee a comfortable retirement, which leads to my advice: When you start your first job, find out about the retirement plan, and start saving right away.

Benefits are based on your past earnings.

Social Security, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation, and disability insurance payments are all partially a function of your past earnings. Those who have earned more have paid more in, and are eligible to receive more benefits. Social insurance programs are explicitly not means-tested. That means that you don’t need to have a financial need to get access to these benefits. Every once in a while Congress complains about someone whose tax return shows an income for the previous year of more than a million dollars, yet they are receiving unemployment insurance benefits. But the point of social insurance is that everyone is covered, regardless of how much money they have.

EVERYDAY Economics

How marriage provides insurance

You may have a lot in common, but you’ll get less insurance marrying someone just like you.

Here’s an important benefit of marriage: It provides something akin to social insurance. Think about traditional wedding vows: Spouses promise to look after each other “for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health.” That sounds like a promise to provide unemployment insurance, disability insurance, and health insurance. Just as unemployment insurance ensures that you’ll still be able to get by when you lose your job, a working spouse effectively provides the same insurance. In both cases, someone—your spouse or the government—will help you pay for groceries if you lose your job. Your spouse can do a better job of insuring you if they don’t face the same risks as you do, which is one reason to marry someone who works in a different occupation or at least for a different employer—you’re less likely to both experience unemployment if you aren’t both working at the same company.

But marriage provides imperfect insurance, because there remains the risk that your spouse will also lose their job. Divorce also provides an escape hatch in which your spouse can fail to provide the promised coverage when a bad event happens.

So far, we’ve examined the redistributive effects of government spending. Let’s now turn to analyzing the redistributive role played by taxes.

The Tax System

All the goods and services, social insurance, and safety net programs funded by the government are paid for by tax payers. You’ve seen so far how spending by the government is used to fight poverty and reduce inequality. Tax dollars fund all of that, but because we don’t all pay the same amount in taxes, the tax system itself reduces inequality.

Federal income taxes are progressive.

Income taxes are taxes collected on all income, regardless of its source. Income includes earned income from wages and unearned income—such as investment income, pensions, and gifts. The 2019 federal income tax bracket for unmarried individuals in the United States is shown in Figure 13. As you can see, the higher your income is, the higher the tax rate that you pay on each additional dollar you earn.

Figure 13 | Federal Tax Rates, 2019

While this suggests that the tax system is designed to make sure higher income people pay a higher share of their income in taxes (that is, that it’s progressive), it isn’t the whole story. Billionaire investor Warren Buffett is often described as the most successful investor in the world. But he’s also known for pointing out that he pays a lower tax rate than his secretary. He calculated that he had paid only around 18% of his income in federal income tax, while his receptionist paid around 30%. Is this a widespread problem? Buffett thinks it is. He said:

I’ll bet a million dollars against any member of the Forbes 400 who challenges me that the average federal tax rate including income and payroll taxes for the Forbes 400 will be less than the average of their receptionists.

No one has taken him up on this bet. Let’s explore why.

Some investment gains are excluded from income taxes.

If you buy an asset for $2,000 and then sell it for $3,000 a year later, the $1,000 gain you make is treated differently from other income. Taxes on such gains are complicated. In 2018, capital gains tax rates were either 0%, 15%, or 20% depending how long you held the asset before selling, as well as your taxable and non-taxable income. But here’s the problem: Super high-income folks—like Warren Buffett—can often find ways to pay the lower rate despite having a high income. And because capital gains tax rates are lower than income tax rates, people who earn much of their income from investment gains end up paying a lower average tax rate than people who earn most of their income in wages.

Higher income people get bigger tax breaks.

There’s a trick when it comes to the income tax schedule—it only applies to your “taxable income.” There are lots of special exemptions that reduce how much of your income counts as taxable income. If you save for retirement, the government rewards you by excluding what you save from taxable income. If you buy a house, the government rewards you by letting you subtract the interest you pay on your home loan from your taxable income. If you’re a student, you may get to subtract some of the tuition you paid from your taxable income.

Taken together, these exclusions reduce the taxable income of the highest earners the most because they spend more of their money on the types of things for which there are special exemptions. That means that exclusions reduce the progressivity in the tax system.

Many other taxes aren’t progressive.

Beyond income taxes, there are a raft of other taxes, which taken together are largely regressive. A regressive tax is a tax where those with lower incomes pay a higher share of their income on the tax compared to people with higher incomes. Taxes based on the things you buy, rather than the money you earn, tend to be regressive. The reason is that the rich tend to spend a smaller share of their income. Because state and local governments tax more of what people buy, these taxes are, on average, regressive. The poorest fifth of households pay nearly 11% of their income on state and local taxes, while the richest fifth of households pay around 7%.

Taxes that fund most social insurance programs are not progressive.

The taxes that fund social insurance programs do not contribute to the progressivity in our tax system. Mostly they are proportional taxes in which we all pay the same percentage of our income regardless of whether we earn a little or a lot. They actually become regressive at the top, because many of these programs cap the amount of income subject to the tax. For example, Social Security taxes are only applied to roughly the first $130,000 of wages. Anything earned over that is not subject to Social Security taxes.

Overall, the tax system is progressive.

Let’s put the pieces together. The basic income tax scale shown in Figure 13 is progressive, taxing the rich at a higher rate than the poor. But the devil lies in the details, and while these details tend to favor the rich, the tax system still remains progressive. Over all, the poorest fifth of all households pay around 16% of their income as tax, while the richest one-fifth pay closer to 30%, although the richest 1% probably pay slightly lower taxes than the rest of this group.