14.1 Monopoly, Oligopoly, and Monopolistic Competition

It’s critically important to tailor your business’s strategy to the specific competitive environment you face. Do you have a lot of competitors, only a few strategic opponents, or are you the only business selling your good? Do you expect new competitors to enter your industry and try to steal market share? Are your products exactly the same as those of your competitors? Or are you offering different goods, better service, or higher-quality products? Together, these factors describe the structure of your market and they determine the extent and type of competition you’ll face.

Market structure is important, because it shapes your market power, which is the ability to raise your price without losing many sales to competing businesses. The more market power you have, the higher the price you can charge.

For instance, if you own the only gas station in town, then you have some market power, because very few of your customers will drive twenty miles for slightly cheaper gas. But if you own one of four gas stations at a busy intersection, then you have almost no market power—if you raise your price even pennies above those of your competitors, your customers will buy their gas elsewhere.

Perfect Competition

A gas station operating at an intersection with other competing gas stations is likely facing a perfectly competitive market. Recall that much of our analysis so far has focused on perfect competition, including our initial analysis of supply in Chapter 3. Perfect competition occurs when your competitors sell an identical good and there are many sellers and many buyers, each of whom is small relative to the size of the market.

No bargain hunting here.

If you’re doing business in a perfectly competitive market, you have no market power. You could try charging more than the prevailing market price, but you’ll lose all your customers to rivals who are offering an identical product at a lower price. And there’s no point charging less than the prevailing price, because as a small business you can sell whatever quantity you want at the prevailing market price. Lowering your price will only lower your profit margin. As a result, your best choice is to be a price-taker, which means that you simply take the market price as given and follow along, charging the prevailing market price.

In addition to gas stations operating at intersections with other competing gas stations, there are a few other examples of perfectly competitive markets: agricultural markets (for example, many small corn farmers, each selling the same product); commodities markets like gold, oil, wheat, livestock (there are many sellers, each of whom is selling nearly identical products to a global market); and the stock market (on any given day, there are thousands of people selling identical stock in Apple, GE, or Ford).

But in reality, perfect competition is relatively rare. Most goods are not identical, and in many markets there are a handful of dominant players. The dearth of perfect competition is a natural result of managers hustling to accumulate market power by differentiating their products, squeezing out their rivals, and deterring new entrants.

So why did we start by learning about perfectly competitive markets? Partly, because it’s simpler. It’s easier to generate insight into the production decisions of businesses when we don’t need to simultaneously consider its pricing decisions. And our supply-and-demand analysis—which is built on perfect competition—yielded useful intuition about how competition plays out. All markets involve some degree of competition, and so these building blocks will be useful as we turn to formulating business strategy.

Okay, that’s it. You’ve just read the last sentence in this book focusing on perfect competition. As we move on, the key new ingredient we’re adding is market power. When you have market power, you don’t want to be a price-taker passively following the prevailing market price. Instead, you need to figure out the price that best exploits your market power. And so our task in the rest of this chapter is to figure out how your competitive landscape shapes your market power, and how that market power leads you to make different pricing decisions.

We’ll start by analyzing monopoly, oligopoly, and then monopolistic competition. But don’t focus too much on the distinctions between these types of markets. Most managers focus instead on their market power, which is aligned along a spectrum.

Monopoly: No Direct Competitors

Is this what a monopoly looks like?

Look down at your pants. See the zipper? Chances are that it says “YKK.” That stands for Yoshida Kogyo Kabushikikaisha, which is the company that makes nearly all of the world’s zippers. YKK is an example of a monopoly, which means it’s the only seller in the market. If you’re a monopolist, you have a lot of market power because you can raise your price without losing customers to your competitors. After all, you don’t have any direct competitors!

Oligopoly: Only a Few Strategic Competitors

Now, look in your pocket. I bet you found a cell phone. And that cell phone probably gets service from Verizon, AT&T, Sprint, or T-Mobile. This is an example of an oligopoly: a market with only a handful of large sellers.

Data from: Statista.

Managers of oligopolistic businesses are locked in a strategic battle for market share. When you have only a handful of rivals, their decisions can have a big impact on your bottom line. And this means that it’s critically important that you think through how your rivals will respond to your choices. Indeed, your best choices depend on how your rivals will respond, just as their best choices depend on how you’ll counter.

Oligopolies have market power, though not as much as a monopolist. That’s because when Verizon raises its prices, it loses some customers, but not all of them. Verizon may hang on to many of its customers because its rivals respond by also hiking their own prices. In some areas the competing networks are too patchy to induce Verizon’s customers to switch. And some customers remain loyal—either out of a strong preference for Verizon, or simply out of inertia.

Monopolistic Competition: Many Competitors Selling Differentiated Products

Now look at your pants. Have you ever noticed how there are thousands of different styles? Just think about jeans. They can be bootcut, straight leg, skinny, or flared. They can also be low-rise, classic, or high-rise. They can be raw denim, acid washed, stonewashed, or vintage washed. You can get five pockets, flap pockets, zipped pockets, or side pockets. They can be done up with a button or zip fly. And they can be dark, neutral, light, or faded; blue, green, red, black, or brown.

Product differentiation yields market power.

Different varieties of jeans have proliferated because sellers are seeking market power through a strategy called product differentiation. By making each product slightly different from their competitors, sellers hope to make each specific variety especially attractive to a particular group of customers. In turn, they figure that you’ll be willing to pay more for a style the more it flatters you. This gives the seller market power, because the most devoted followers of a particular brand or style will stick with it, even if the price is higher. Product differentiation doesn’t just involve differences in what you sell. Savvy managers also differentiate their products based on brand image, quality, store location, customer service, return policies, and packaging. Successful product differentiation can create market power even when you face hundreds of competing sellers, because some customers want the precise variety you offer, and they’ll pay a little more to get it. In other words, the more distinct you make your product, the less your rivals’ products will be a close substitute.

The jeans market is an example of monopolistic competition. This occurs when there are many competing businesses, each selling somewhat differentiated products. It’s a useful term, highlighting the fact that such markets are both monopolistic and competitive. The jeans market is monopolistic because there’s only one seller making each specific model of jeans. But it’s also competitive because there are dozens of businesses competing to sell you jeans.

Market Structure Determines Market Power

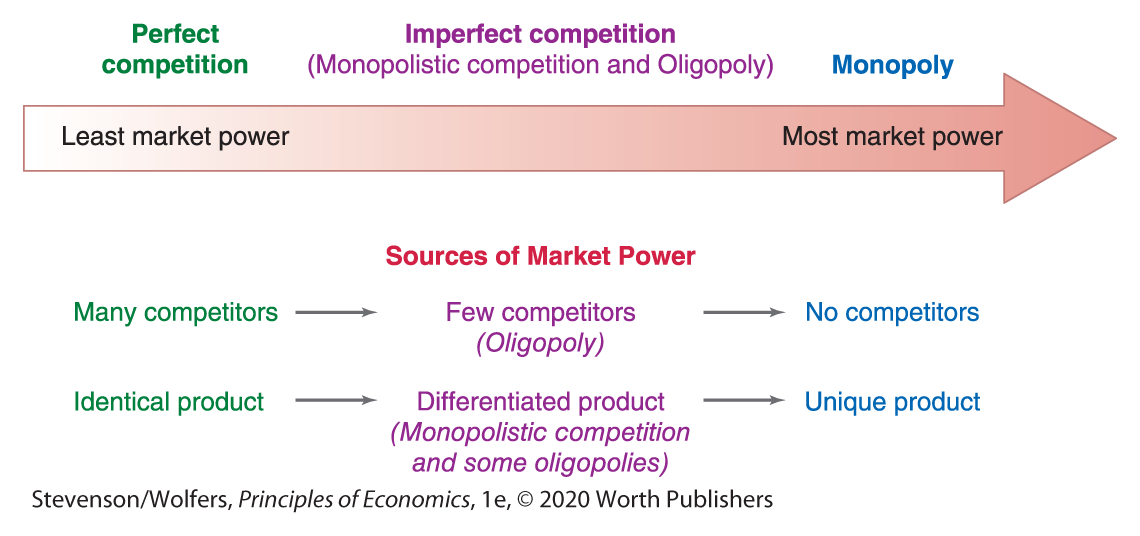

The structure of your market matters, because it shapes your market power. As Figure 1 shows, the structure with the least market power is perfect competition, where many small businesses sell identical products. At the other extreme, monopolists have the most market power, because they’re the only business selling a unique product. Rather than focusing on sharp distinctions between these market structures, Figure 1 emphasizes that there’s a spectrum along which some businesses have more or less market power.

Figure 1 | The Spectrum of Market Power

The lower part of Figure 1—the bits below the large arrow—shifts attention from the four specific market structures to the underlying sources of market power. It illustrates that you have more market power when you have fewer competitors, and when your products are more unique.

Perfect competition and monopoly are both rare.

Even a monopolist in the zipper market faces competition in the broader market for fasteners.

In reality, few businesses populate the extremes of this spectrum. Perfect competition is rare, because your competitors rarely sell products that are identical to yours. For instance, even though competing gas stations sell similar products, they differ in convenience (some are closer to your house than others), their gas includes different chemical additives, and they offer different customer service. Likewise, pure monopoly is rare. Once you broaden your definition of the market sufficiently, you’ll find that every business faces at least some competition. For instance, even though YKK dominates the zipper market, its customers could always use button flies instead, which means that YKK has competitors in the broader market for fasteners.

Most businesses operate in imperfectly competitive markets.

It’s most likely that your business will lie in the intermediate range of imperfect competition, which includes monopolistic competition and oligopoly. The term is apt, because you’ll face competition, but it will be imperfect—either because you only have a few competitors or because you sell somewhat different products than your competitors.

An earlier generation of economists focused on drawing sharp distinctions between monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly. But over time, economists have come to understand that different industries don’t neatly fit into one bucket or the other, partly because the structure of markets is constantly evolving.

We’ll take that more modern view, focusing on the broader insights that apply to all imperfectly competitive markets. This view emphasizes that there’s a spectrum of market power, reflecting the number and type of rivals, and how different their products are. It recognizes that your business doesn’t operate in a static market structure, but rather in a competitive environment that changes in response to the strategies employed by dueling businesses. And it recognizes that your best strategies depend on the particulars of your specific market. That’s why we’ll focus less on market structure, and more on the “deep forces” which both shape your business’s market power, and inform the strategies that managers pursue.

Five Key Insights into Imperfect Competition

Our brief tour so far points to five big insights that will set the agenda for the rest of our study of business strategy.

Insight one: Market power allows you to pursue independent pricing strategies.

The pricing strategies you’ll want to pursue in imperfectly competitive markets are sharply different than those you’d employ under perfect competition, where you’re a price-taker who simply charges the prevailing market price. Instead, when you have market power, you can set your own price, but you face a difficult balancing act: Raising your price will boost the profit margin on each item you sell, but it’ll also reduce the number of items you sell. Managing this balancing act is crucial to earning a healthy profit. It’s so important that we’ll spend the rest of this chapter exploring how managers in imperfectly competitive markets set their prices.

You can also use your market power to charge different people different prices. Do it right and you’ll both expand your market and boost the profit margin you earn on your most devoted customers. We’ll explore how to do this in Chapter 17, on Sophisticated Pricing Strategies.

Insight two: More competitors leads to less market power.

The more competitors selling their wares in your market, the less market power you’ll have. The logic is simple: If your customers have many good alternatives to buying from you, they’ll be less likely to stick with you if you raise your price. When new rivals enter your industry, they both grab your market share and reduce your market power. If the competition is fierce enough, your competitors may compete away all of your profits.

It follows that your long-run profitability depends on how many rival businesses enter your market. That in turn depends on whether there are barriers preventing the entry of new businesses into your market, and how porous those barriers are. But those barriers to entry aren’t simply a naturally occurring defense—to some degree, they’re also the result of your strategic choices. These strategic choices are so central to your long-run profitability that we’ll devote all of Chapter 15, on Entry, Exit, and the Long Run to assessing the strategies you can pursue to deter new entrants from competing your profits away.

Insight three: Successful product differentiation gives you more market power.

The more different your product is from that sold by your rivals, the less likely it is that your customers will find them to be a useful substitute if you hike your price. As a result, successful product differentiation gives you more market power.

Savvy managers understand that these differences in product attributes are not a fixed attribute of your market. Rather, you get to choose the attributes of your product, and so you face an important strategic choice about how best to position your products. Smart product positioning can boost your market power and hence your profitability. These decisions are a key part of the marketing function in most businesses, and they’re sufficiently important that we’ll spend the first half of Chapter 16, on Business Strategy, figuring out how best to position your product.

Insight four: Imperfect competition among buyers gives them bargaining power.

So far we’ve mostly focused on the imperfect competition between rival sellers in a market. But in many cases, there’s also imperfect competition among a limited number of buyers, making it important for managers to keep their most valuable clients. This gives buyers a degree of bargaining power which they’ll use to demand lower prices.

You’ll want to use this insight to negotiate a better deal with your suppliers. After all, you’re not just a customer—you’re one of their most valuable clients. But realize that your big customers will also try to exploit their bargaining power to extract a better deal from you. Ultimately, your profits depend on managing this conflict well—using your bargaining power as a valued client to extract low prices from your suppliers, while fending off demands from your important clients that you lower the price you charge them. We’ll dig more deeply into how to improve your bargaining power in the second half of Chapter 16, on Business Strategy.

Insight five: Your best choice depends on the actions that other businesses make.

The interdependence principle is particularly important in imperfectly competitive markets, as your best strategic choices likely depend on the choices that others make. And their best choices also depend on the decisions that you make.

This interdependence arises in all of the strategic decisions described above, including pricing, entry, product positioning, and bargaining with buyers and suppliers. For instance, the best price for your goods depends partly on the prices offered by your rivals, and whether they’re trying to steal your customers. This interdependence is so fundamental to business strategy that we’ll devote all of Chapter 18 to Game Theory and Strategic Choices, so that you develop the tools you’ll need to analyze strategic interactions.

Do the Economics

Assess the market power of the following sellers:

We’ve set the agenda for the next few chapters. It’s time to focus on our first task. As a manager with market power, you’re no longer a price-taker, so you need a pricing strategy.