16.2 Non-Price Competition: Product Positioning

The product that your business sells is probably quite similar to that sold by some of your competitors, and quite different to that sold by others. Too often, managers think about these similarities and differences as somehow innate to their product (and those of their competitors). But that’s a mistake. After all, you get to choose what features to include, the quality of your workmanship, the type of service to offer, your product design, its style, the locations where it’s sold, and the way you advertise it. As you make these choices, you effectively choose how to differentiate your product from those of your rivals. And this choice—of how best to position your product—is a key strategic decision that shapes your market power and ultimately your profitability.

The Importance of Product Differentiation

Perhaps the simplest way to appreciate the importance of product differentiation is to see what happens in its absence. And to see that, we’ll visit a local highway, so that you can put yourself in the shoes of Hilda Perez, who owns a Shell gas station. Her gas station sits right across the street from a BP station, although apart from this one rival, she doesn’t face much competition because there are no other gas stations for miles. But Hilda sells a product—gasoline—that’s virtually identical whether you buy it from her Shell or from the nearby BP. It’s the same chemical compound, sold at the same location, and both gas stations accept the same credit cards and offer similarly polite service. Let’s see how competition plays out in the absence of product differentiation.

Pure price competition can drive your economic profits to zero.

Competing on price

Initially, both Hilda’s Shell and the rival BP sell gas for $3.90 per gallon, and they each make a tidy profit, because the wholesale price is only $3.65 per gallon. Given that they’re both charging the same price, they’re probably each selling to half the customers. Now, put yourself in Hilda’s shoes, and think about what to do next. If you drop your price to $3.89, you’ll win over your rival’s customers, and with twice the sales, your profits will nearly double. Good idea. But let’s see how your rival responds, now that they’re selling no gas. He realizes that he can get all of his customers back if he cuts his price to $3.89. Better still, he can cut his price to $3.88, and also win over all of your customers, too. So he cuts his price to $3.88. Now you discover you’re selling no gas. What’s your best response? The smart thing is to cut your price to $3.87, and win all the customers back. And when your rival discovers this, what’s his obvious response? He responds by cutting his price to $3.86.

As each price cut is matched by a further cut, eventually BP is charging $3.66, just a penny above its marginal cost. Even then, Hilda’s best choice is to cut her price to

Hilda’s experience contains a warning for all executives: If you sell identical goods—that is, if you don’t differentiate your product—then competition from even just one rival can force the price so low that it eliminates your economic profits.

Non-price competition through product differentiation yields market power.

The problem that Hilda faces is that if the rival gas station cuts its price, she will lose all of her customers, and her rival finds this an irresistible incentive. More generally, the problem that any business selling identical goods faces is that there is a huge incentive for their rivals to undercut their price. This incentive is particularly strong when competitors sell identical products because gaining even a small price advantage will translate into a large change in the quantity demanded. This suggests that the key to avoiding price competition is to weaken the incentive for your rival to undercut your price.

This is where non-price competition comes in. If you differentiate your product so that it better suits some of your customers, then those folks will keep buying from you, even if your price is not the lowest. Through successful product differentiation, you’ll gain market power.

A price cut on Pepsi means nothing to her.

To see how important this can be, contrast the very different way that competition plays out between Hilda’s Shell and the nearby BP, with the competition between Coke and Pepsi. In both the gas and cola markets, suppliers sell chemically similar—indeed, nearly identical—products. And both are locked in a fierce contest with their rivals. What’s different is the type of competition. The prices at many gas stations are literally four feet high, while ads for Coke or Pepsi almost never mention the price.

That’s because Coke and Pepsi don’t just compete on price. Coke implores you to “Taste the Feeling,” (as if you can taste a feeling) and Pepsi boasts that it’s the drink for those who want to “Live for Now” (as if there’s some other time to live). They’ve each differentiated their products, so that despite the chemical similarities, each cola has a devoted following. I’m sure you have friends who stick with Coke even when Pepsi is cheaper (just as other friends stick with Pepsi even when Coke is cheaper). As a result, their customers—like their beverages—are somewhat sticky.

This has big implications for how competition plays out. It blunts Pepsi’s incentive to undercut Coke’s prices since a price cut won’t translate into many new customers. By making your rival’s product an imperfect substitute for yours, you effectively blunt their incentive to undercut your prices. This makes price competition less fierce, which is why both Pepsi and Coke sell for prices well above their marginal costs.

The contrast between cut-throat price competition in the market for gas and the larger profit margins in the market for cola highlights the importance of finding ways to differentiate your product.

There are many ways to differentiate your product.

Product differentiation is about finding ways other than a lower price to attract and retain customers, and there are many ways to do this. You could offer different features, like HP and Dell who compete by offering computers with different combinations of memory, hard drive size, and processor speed. Quality is important too, and Gibson handcrafts its guitars to create a sweeter sound than a factory-made alternative. Customer service matters, which is why Nordstrom hires more people to help you shop than Walmart does. Design counts, which is why Target collaborates with leading designers to create more interesting homewares than Kmart. Style is essential, and Diesel competes with Levi’s by trying to offer more fashionable jeans. Reliability is important, and LL Bean backs up its outdoor gear with an impressive money-back guarantee. Location and convenience are time-savers, and this is a key part of the competition between banks. And even beyond these objective differences, advertising can persuade some customers, which explains why Pepsi and Coke spend so much money trying to convince you to prefer one similar-tasting cola over another.

There’s fierce competition at each of these margins—in features, quality, service, design, style, reliability, location, and brand image. And that’s why you shouldn’t think of them as fixed characteristics of your product, but rather as strategic choices you make to best position your product. A successful strategy will give you more customers who are loyal, effectively redrawing your business’s demand curve so that it’s in a more profitable place. That’s why our next task is to develop the tools you’ll need to figure out how best to position your product.

Positioning Your Product

The idea of product differentiation is to offer your customers a product that better serves their needs. The payoff is that your customers will still want to buy from you, even if you charge a slightly higher price than your rivals.

So you know differentiation is important, but how should you decide the best ways to differentiate yourself? This is about you choosing the set of attributes—the features, service, brand image, and so on—for your product. The answer depends on how you can best position your product relative to your competitors’ products. As we’ll see, it involves a delicate trade-off between demand-side considerations, positioning your good to be attractive to as many customers as possible, versus supply-side concerns, positioning it to be as different from your competitors as possible. It’s a balancing act with big implications. Position your product too close to your rivals—that is, make it too similar—and you risk more intense price competition, leading to lower prices and lower profits, as in the competition between Shell and BP. Position your product too far away—perhaps by including unusual features—and you’ll find it hard to win customers from your rivals.

In order to analyze this trade-off strategically, we’ll begin with a metaphor. While it might seem a bit contrived, stick with it, because we’ll soon see how businesses actually use this framework—sometimes called the Hotelling model (after its founder, Harold Hotelling)—to figure out how to best position their products.

The beach as a metaphor for non-price competition.

Here’s a very simple story to illustrate non-price competition. It’s a hot day out, and so people are spread all along the beach. You’re an ice cream seller and have to decide where to position your ice cream cart. This decision is important, because you’re not the only ice cream seller, and people will only walk to the nearest cart. For simplicity, we’ll assume that people are evenly spaced along the beach, and you have only one rival.

Where are you going to position your ice cream cart? Figure 2 illustrates where your rival is, and two possibilities you might choose.

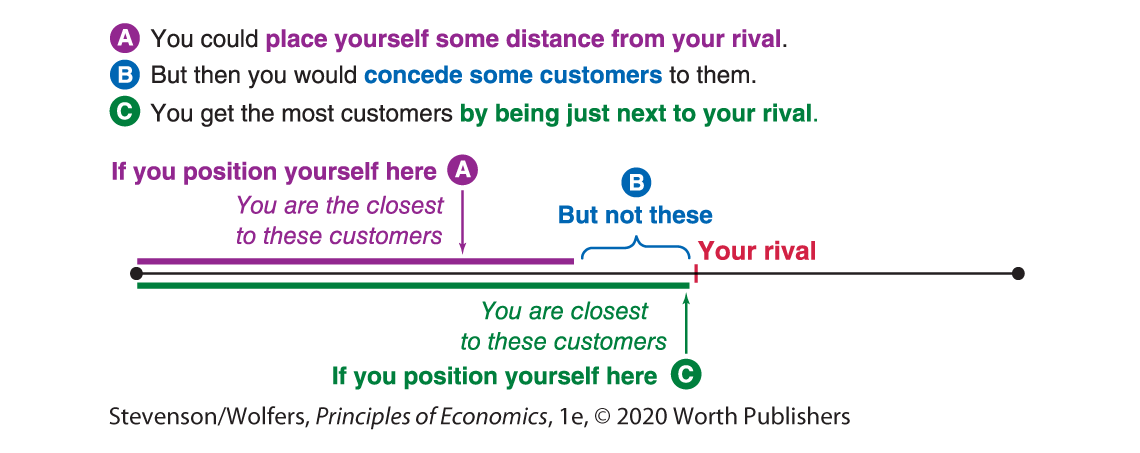

Figure 2 | How Should You Position Your Product?

First, take note of where your rival is located, because you want to choose the best position, relative to them. To gain the most sales, you want to position your cart so that your cart is the most convenient one for as many customers as possible. In this case, your rival is on the right end of the beach. You should position your cart so that you can supply the underserved part of the market, which in this case is the left end of the beach. Doing this will win you all the customers to your left, as well as half of those between you and your rival. You can see that this is a better outcome, because it yields more customers than if you had taken the position to your rival’s right.

Your business’s position is a metaphor for the type of product you offer.

Okay, that’s it: You’ve now made your first product-positioning decision. And the example can be applied to the many other businesses that regard their location as the most important strategic positioning decision they face.

But it also applies beyond choosing a location. Let’s see how we can extend this metaphor to help you think about the positioning of many other products, relative to their competitors. In each case, the trick comes in trying to sort out the important dimensions in which you and your competitors differ.

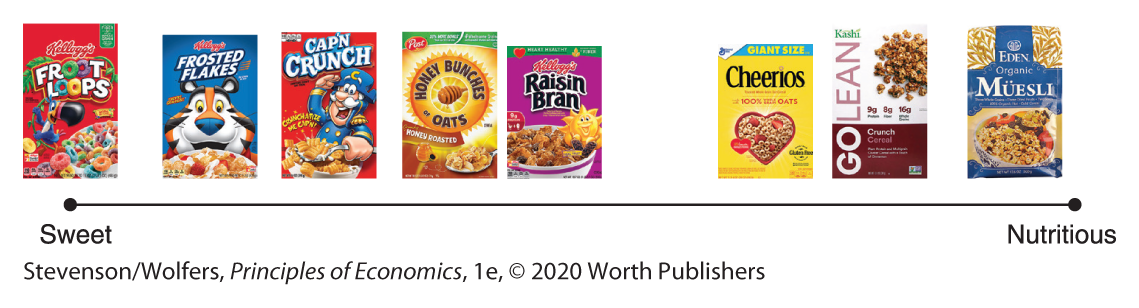

- A product manager at Kellogg’s doesn’t choose where on a beach to locate, but rather where to position their new breakfast cereal on a continuum from sweet to nutritious.

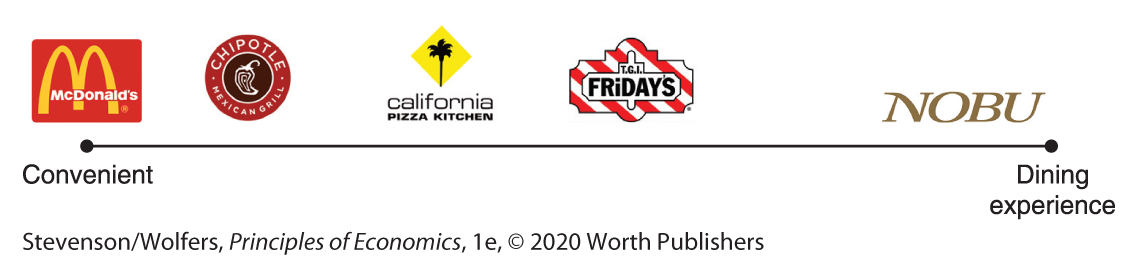

- A restaurateur doesn’t decide between the left or right end of the beach (or somewhere in between), but rather between offering convenient fast food or a more elaborate dining experience (or something in between).

- Automotive engineers design new car models somewhere on the spectrum between compact, fuel-efficient cars at one end, and larger, more powerful gas-guzzlers at the other.

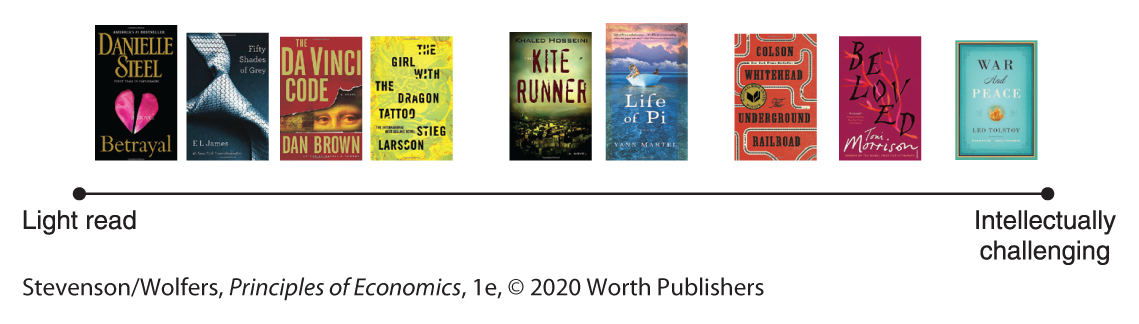

- Even in art, product positioning matters. Writers have to place their work somewhere on the spectrum between an enjoyable light read and a challenging intellectual work.

Let’s return to the beach, and try to decide exactly where to position your ice cream cart. We’ll start with the demand-side considerations figuring out how to position your product to appeal to the most customers, and then turn to the supply side.

Demand side: Position your product next to your rival to get the most customers.

We’ve already decided to place your ice cream cart to the left of your rival so that you cater to the underserved part of the market. But now the question is how close to place it. The answer shown in Figure 3 might surprise you.

Figure 3 | How Close Should You Position Your Product to Your Rival?

When you only face one rival, you want to position your offering as close as possible to them. Why? If you’re on your rival’s left, then you’ll definitely be the preferred choice of every customer to your left, but you’ll only be the nearest choice for half of the customers between you and your rival. Those folks are the marginal customers that you could win over by moving just a little closer to them. Every time you shift closer to your rival, you’ll start to win more and more marginal customers. Notice that the folks to your left don’t have a better option, and so they’ll still come to your ice cream cart, even if you shift a bit farther away. And so you should keep shifting closer to your rival until you’re just next to them. At that point, you’re selling to as many customers as possible, given where your rival is. Yes, the folks all the way at the left end of the beach will be frustrated at having to walk farther, but you’re going to get their business anyway.

The bottom line here is that demand-side considerations suggest that making your product more attractive to as many customers as possible means positioning yourself just next to your rival.

Interpreting the DATA

Why are political parties so similar?

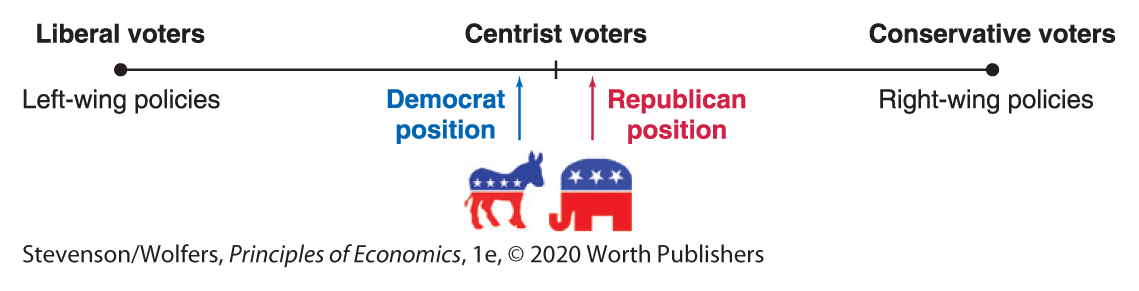

It’s easy to get disillusioned by politics, and some people say that elections don’t offer a real choice. They say that sure, there are two parties, but they’re so similar on most issues that it doesn’t really matter who wins.

But if you think about policy platforms as an example of product positioning, this is exactly what you should expect. In this case, the left end of the beach represents left-wing ideas (such as more government spending on the social safety net, paid for with higher taxes), and the right end of the beach represents right-wing ideas (such as less government spending and lower taxes). Instead of thinking about beachgoers scattered at different locations along the beach, think about the preferred policies of different voters scattered at different locations along this left-wing/right-wing spectrum.

Just as the ice cream vendors want to be close to as many beachgoers as possible, politicians want their policies to be close to the preferences of as many voters as possible because that’s what’ll help them persuade more folks to vote for them. The result is that the Democratic and Republican candidates each find it easier to get elected if they set their policy positions quite close to those of their opponents. As each party jockeys to cater to the underserved end of the voter pool, they end up converging in the middle, both trying to win centrist voters—a finding known as the median voter theorem.

Of course, the two parties do differ a bit—some people say they differ quite a bit—so perhaps this finding is best viewed as explaining why they don’t differ even more.

Supply side: Position your product away from your rival to reduce price competition.

So far, we have only analyzed the demand side of the market and the incentive to be as close as possible to your customers. But you also need to consider the supply side, and how your rivals might respond. Now it’s time to invoke the interdependence principle to think through how your product positioning affects the prices your competitors set.

As we learned from the neighboring gas stations, if you position yourself right next to your opponent so that you’re offering essentially identical goods, then intense price competition will push down prices and profits. When your positions are nearly identical, you have no market power.

By contrast, if you position your product far apart from your rival, many of your customers will find your rival’s product to be a less useful substitute for yours, giving you some market power. The result will be less downward pressure on your prices. For instance, rather than positioning your gas station across the street from your rival, you could choose a location in the next town. It’s likely that you’ll win most of the customers in that town, and your rival will win most of the customers in their town. The advantage of positioning your gas station some distance away is that a small price cut is unlikely to lead many customers to switch gas stations, reducing the incentive for either of you to try to undercut the other’s prices.

The bottom line here is that you want to position your product to reduce the incentive for your rivals to undercut your price. The more that you position your products so that they’re different from those offered by your rival, the more market power you’ll have, allowing you to charge higher prices and enjoy larger profit margins. For instance, HP and Dell sell very similar Windows-based computers, and so the fierce competition between them has led to razor-thin profit margins. But Apple has chosen to position itself as offering quite a different type of computer, and its prices and profit margins are much higher.

EVERYDAY Economics

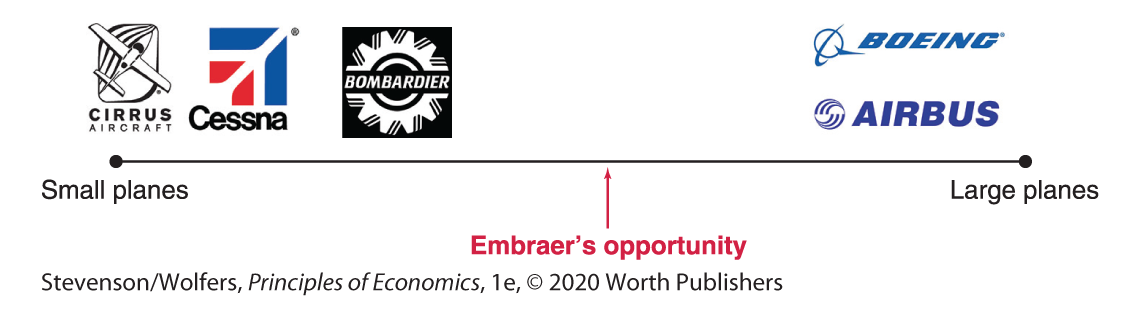

Can you make a dent in the airplane market?

Smaller, but profitable

Much of the attention paid to airplane manufacturing focuses on the two giants, the U.S.-based Boeing and the European-owned Airbus, who both make the large jets that seat hundreds of people. The Canadian company Bombardier makes the Lear jet and other smaller planes used largely as corporate jets. Cessna makes small planes that seat a dozen or fewer people, and Cirrus mainly makes planes for hobbyist pilots. The CEO of the Brazilian company Embraer is trying to decide how to position his company’s planes. What’s your advice?

The rough sketch above gives you a sense of how Embraer saw the market. Boeing and Airbus are engaged in a brutal price war for the large plane segment, and it makes no sense to join that fight. Instead, it went looking for an underserved niche in the market. Embraer discovered that neither of these giants bothered making medium-sized planes with 70 to 118 seats, and the traditional small-jet manufacturers didn’t have the capacity to build planes that big. Embraer positioned itself to dominate this niche, building jets that have proven to be very popular among regional airlines like American Eagle. And because there is not much price competition—no one really makes a good substitute for its medium-sized planes—this niche has proven to be very profitable for Embraer.

Recap: There is a product positioning trade-off.

Let’s wrap up what we’ve learned from all of this. The question of how to differentiate your product is really about how best to position your product. There are two competing forces to consider:

Demand side: Consider your customers. You want to position your product so that you’re closer than your rival to the preferences of as many customers as possible, which means positioning your product on the underserved end of the market. But once you’re serving this part of the market, the same logic says you should try to locate closer to your rival—that is, make it as similar as possible—so as to maximize the number of customers who prefer your product.

Supply side: Consider your competitors. You want to position your product so as to minimize the incentive for your rivals to undercut your prices. This is a countervailing force to position your product away from your rivals—that is, to differentiate your product—so as to soften price competition, which yields market power and larger profit margins.

Putting these together says that positioning your product closer to your rival can help increase the quantity you sell, while positioning it further away boosts your market power and hence the profit margin on each item you sell. Because both the quantity you sell and your profit margin matter, this is a difficult trade-off to manage. There are no hard and fast rules about how to get it right, but rather some basic rules of thumb:

- If price competition is particularly intense—as it is between neighboring gas stations—you want to differentiate your product (as Coke and Pepsi do).

- If price competition is subdued (as in elections, where politicians are not allowed to buy votes), then you want to minimize any differences, so that you can appeal to as many people as possible.

One approach to positioning your product is through advertising, and so our next task is to apply these ideas to putting together a successful advertising campaign.

The Role of Advertising

Advertising is an essential part of a successful product positioning strategy. It’s so important that businesses spend hundreds of billions of dollars on advertising every year, which is enough to support the TV shows you watch, the newspapers you read, and the web content you enjoy.

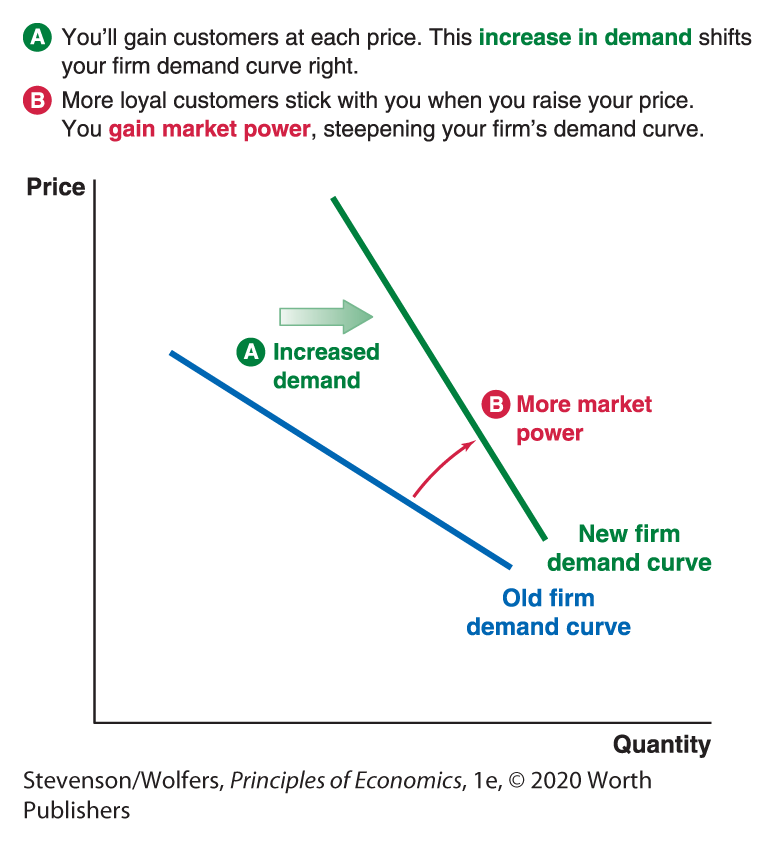

Advertising aims to shift and steepen your firm demand curve.

A successful advertising strategy will shift your firm demand curve in two important ways, which are illustrated in Figure 4. First, by convincing more people to buy your product at any given price, it increases the demand for your product. This shifts your firm demand curve to the right, allowing you to sell a larger quantity. And second, if your advertising campaign builds brand loyalty, then your customers will stick with you even if you raise your prices. These price-insensitive customers increase your market power, which translates into a steeper or more inelastic firm demand curve and larger profit margins. Both of these changes will boost your profits.

Figure 4 | Advertising Shifts Firm Demand

Market structure shapes your advertising strategy.

The structure of competition in your market shapes the impact of different types of advertising, and that in turn determines the messages you’ll want to emphasize.

In a perfectly competitive market it rarely makes sense for an individual business to advertise. After all, when you’re only a tiny part of the market, your campaign to convince people to “eat more beef” will benefit other farmers a lot more than it’ll benefit you. The only way advertising makes sense is when it’s coordinated and paid for by an industry association, such as the Cattlemen’s Beef Board—which all beef farmers contribute to—with its message: “Beef. It’s What’s for Dinner.”

Monopolies use advertising to shift the market demand curve for their product. DeBeers, which for a long time was a monopolist in the diamond market, used its marketing muscle to help create the modern custom that couples celebrate their engagement with a diamond ring. An increase in demand for diamonds benefited DeBeers exclusively, and so its advertising focused on the product, rather than the brand, as in its famous tagline, “A diamond is forever.”

Under imperfect competition it’s typically worth advertising even more aggressively because you have an extra incentive beyond increasing demand for your product: Advertising can also help you steal customers from your rivals. To do this effectively, you should emphasize your particular product positioning and the unique value that your product offers. For instance, rather than arguing that chocolate is delicious, M&M’s remind you that it’s the only chocolate that “melts in your mouth not in your hands.” Likewise Visa doesn’t describe how useful credit cards are, but rather that it is the world’s most widely accepted credit card—“Everywhere you want to be.” And Subway’s slogan “Eat Fresh,” is a subtle dig at the quality of its fast-food rivals.

Search goods lend themselves to informational advertising.

The characteristics of your product will also influence the type of advertising you should do. A search good is any good that you can easily evaluate before buying it. For instance, a desktop computer is a search good, because once you’ve read a list of its specifications—such as the type of processor it uses, the size and speed of the hard drive, and the amount of memory—you can figure out whether it provides good value for your money. (In contrast, Pepsi is not a search good because you have to taste it to really evaluate it.)

Search goods lend themselves to a type of advertising strategy called informative advertising, which aims to inform you about a product. The idea is to provide your potential customers with hard data about the specific attributes of your product. Whenever you click on a company’s homepage, you’ll probably discover informative advertising. Computer companies catalog the components they use, law firms list the qualifications of their staff, and investment companies describe their recent performance. Generally, economists believe that informative advertising is helpful, as better information leads people to make better choices.

When customers are uncertain about quality, branding can help.

Branding can be an especially important part of advertising for goods where buyers can’t easily discern their quality. It’s a lesson you’ll recognize from the last time you got hungry on a road trip. As you’re scanning the exits far from home, you quickly realize that you don’t know whether the local diner serves quality burgers or health code violations topped with lettuce and tomato. This uncertainty about the quality of the burger leads millions of people to pull over at the nearest McDonald’s, instead.

Versions of this story play out not only at thousands of highway rest stops every day, but also in any market where customers are uncertain about the quality of the goods they’re buying. And they illustrate how effective branding provides information to consumers about the quality of your goods. Through careful brand management, McDonald’s convinces you its burgers will be safe, Tiffany convinces you its diamonds aren’t fake, and Apple convinces you its phones won’t be faulty. Even better, it’s a self-reinforcing cycle, because the stronger a brand’s reputation for quality, the greater the stake it has in maintaining that reputation.

Persuasive advertising aims to persuade.

But advertising often contains very little information. Instead, persuasive advertising tries to persuade or manipulate you into believing that you’ll enjoy a particular product. Persuasive advertising often exploits your emotions, and uses subtext to hint at claims that are not actually true.

Are you persuaded?

When Pepsi tells you to “Live for Now,” and Coke says you should “Taste the Future,” neither provides any information that’ll help you choose the tastier or less unhealthy beverage. It’s hard to see how this advertising leads buyers to make better decisions, and it might lead them to make worse ones.

A lot of advertising may be wasteful.

Indeed, the main effect of Pepsi’s advertising might be for it to win business from Coke. This is called a business-stealing effect. And it means that while it’s privately profitable for Pepsi to advertise, from society’s perspective it’s wasteful, because Pepsi’s gains are offset by Coke’s losses. Similarly, if Coke’s advertising only helps it steal business from Pepsi, then its advertising campaign is also socially wasteful.

It may even be worse than this. Part of the reason that Pepsi spends so much on advertising is that it can’t afford to lose market share when Coke advertises. Likewise, Coke advertises because Pepsi does. The result is an advertising arms race, in which each brand is forced to advertise just to keep up with the amount of advertising by their competitors. This suggests that much of the $180 billion spent each year on advertising may be socially wasteful.

Recap: Product positioning is about non-price competition.

OK, now it’s time to pan back to the big picture. At this point, you should have a good sense of the first of the five forces—how best to compete with your existing rivals in the market through both price competition and strategic product positioning, including advertising. The second force—the threat of new entrants—was the focus of the last chapter, while the third major force, the threat of substitution was also discussed in detail earlier. So let’s now turn to the fourth and fifth forces: The threats posed by the bargaining power of your customers and your suppliers.