17.1 Price Discrimination

They’re each paying a different price to be there.

How expensive is your college? Ask around to find out what your classmates are paying. Chances are the price you’re paying is quite different. Even though your college pretends that there’s just one price for everyone—or at least one price for in-state students if you’re at a public university—that’s not true. Sure, it charges everyone the same annual tuition. But that’s not the actual price. The price you actually pay for college is the annual tuition charge, minus the grants and scholarships that you receive. Grants and scholarships are discounts given to particular customers. Once you take these discounts into account, the price you’re paying for college may be many thousands of dollars higher or lower than the person sitting next to you in your econ class. And so even though you’re receiving the same education as your classmate, you’re each paying very different prices.

Your college is following a sophisticated pricing strategy. It has figured out that it can reap a lot more revenue and attract better students by charging different people different prices, even though they’re purchasing the same product. Our analysis in previous chapters has focused on the case where businesses charge everyone the same price. It’s time to explore how businesses increase their customer base and earn higher profits by charging different people different prices for the same good.

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination is the strategy of selling the same product at different prices. For instance, once we take into account the “discounts” given in the form of grants and scholarships, the price that leading private colleges charge a typical freshman could be as low as $0 for a gifted student from a low-income family, or as high as nearly $60,000 per year for a freshman from a high-income family.

Interpreting the DATA

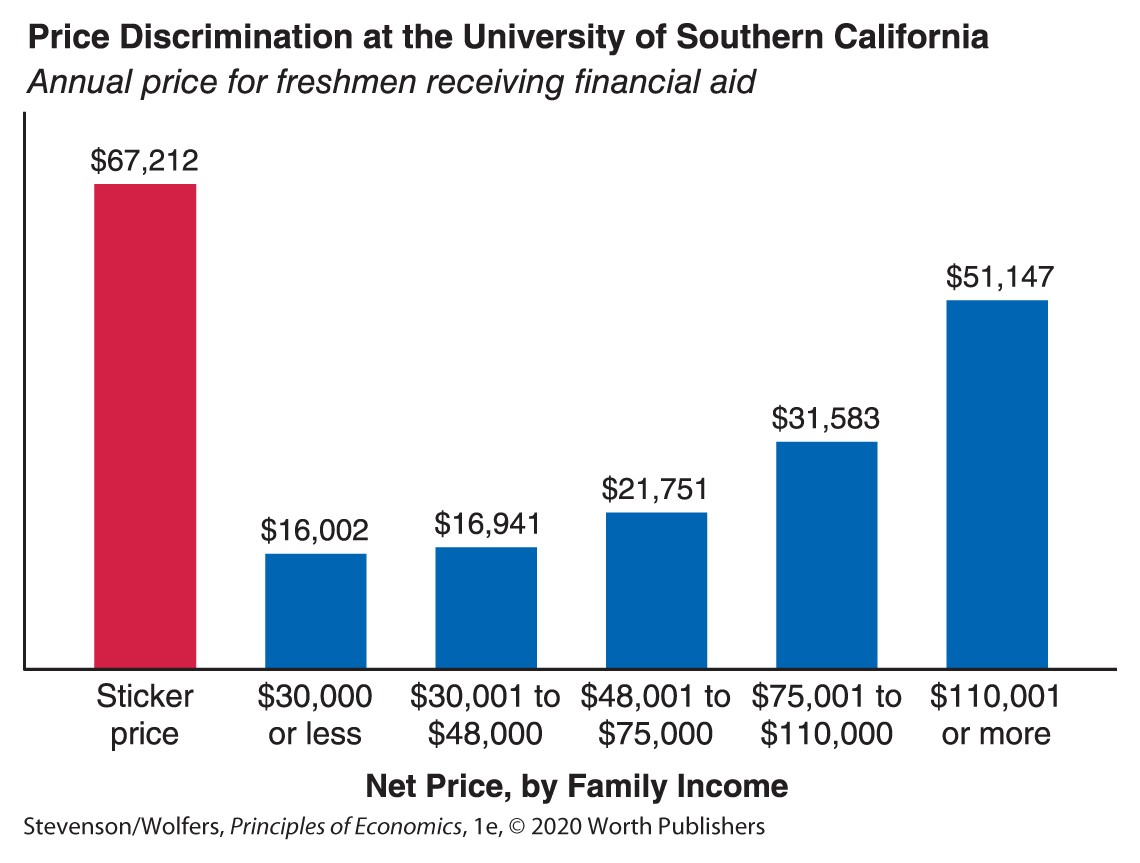

How much price discrimination is there at college?

2015–16 academic year data from: Tuitiontracker.org.

The price of college varies enormously. As the figure to the left shows, the “sticker price” to attend the University of Southern California is $67,212. But few people actually pay that price. Students from relatively low-income families—those with a family income at or below $30,000—pay, on average, $16,002. By contrast, students from affluent families—say, those with family incomes over $110,000—pay, on average, $51,147. And there are even differences within each of these income groups, with some people paying more, and others paying less.

Want to see how much price discrimination there is at your college? Point your browser to tuitiontracker.org, and explore how the price paid by your classmates varies, depending on their family’s income.

Set prices close to (and just below) marginal benefit.

As a profit-oriented manager, the goal of your price-discrimination strategy is to charge each individual customer the highest price you can get away with. We call the maximum price that a customer will pay their reservation price.

What determines your customers’ reservation price? If buyers follow the cost-benefit principle, the most each is willing to pay for something is their marginal benefit.

And so your goal should be to charge each customer a price that’s just below, but as close as possible to their reservation price, which is also their marginal benefit. You’ll leave your customers willing to purchase your product—but just barely. The case in which you get this targeting exactly right—so that you charge each customer their reservation price—is known as perfect price discrimination. Succeed at this, and you’ll achieve two profit-boosting objectives:

- Charging the highest price you possibly can on each sale; and

- Make every possible sale where there’s a customer whose marginal benefit exceeds your marginal cost.

The practical challenge in implementing a successful price-discrimination strategy is sorting out which customers need a low price to be induced to buy your product, and which customers will pay more if you charge them a higher price. It’s a problem because your customers aren’t going to tell you when they have a higher reservation price. We’ll set this problem of figuring out each customer’s reservation price aside for a few pages, but then we’ll return to spend the rest of the chapter solving it.

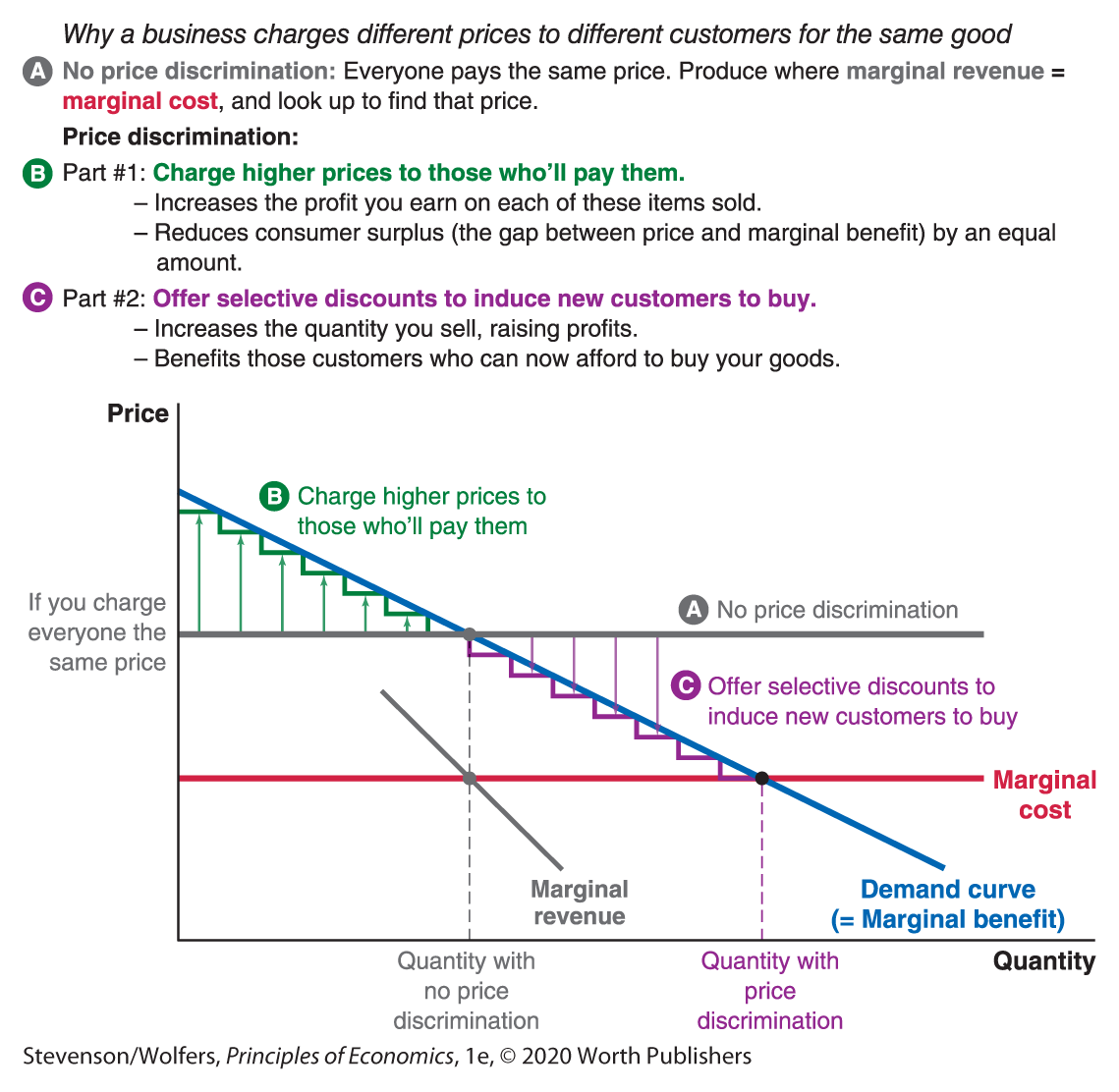

For now, note that because the demand curve is also the marginal benefit curve, it reveals each customer’s marginal benefit, and hence reservation price. Thus, setting the price you charge each customer to be just below their reservation price means setting prices just below the demand curve. The stepped line in Figure 1 illustrates a nearly perfect price-discrimination strategy in which the price charged to each customer is just a smidge below their marginal benefit.

Figure 1 | Price Discrimination

Price discrimination leads to higher prices for some and lower prices for others.

It’s worth comparing this sophisticated pricing strategy with the simpler alternative of no price discrimination when you charge all your customers the same price. That’s the case we analyzed in Chapter 14, and hopefully you recall that a manager with market power first chooses their quantity at the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost, then chooses their price by looking up to the blue demand curve. Consequently, with no price discrimination, everyone pays the same price, shown as the gray line in Figure 1.

By comparison, the stepped line in Figure 1 reveals that a successful price-discrimination strategy has two parts: Charge higher prices for some customers (the green part of the stepped line), and charge lower prices for others (the purple part). We’ll analyze each of these in turn.

Part one: Charge higher prices to those who’ll pay them.

You can charge a higher price to those customers who have a higher marginal benefit because they’re the customers with a higher reservation price. Higher prices for high-marginal-benefit customers are illustrated by the green part of the stepped line in Figure 1. As long as this higher price doesn’t exceed your customers’ marginal benefit, they’ll still buy your product, and you’ll enjoy a higher profit margin on each sale.

Your gain from these higher prices comes at your customers’ expense—your profits rise because they’re paying more. This reduces their consumer surplus, which is the gap between their marginal benefit and the price they pay. They’ll be unhappy about this, but their loss is your gain, boosting your producer surplus, which is the gap between the price they pay and your marginal cost. Thus, the “higher prices” part of a price-discrimination strategy redistributes economic surplus from buyers to sellers, but it doesn’t increase the total amount of economic surplus.

Part two: Offer selective discounts to induce new customers to buy.

You should also offer discounts to potential customers who wouldn’t otherwise be willing to buy your product. Lower prices for these potential new customers are illustrated by the purple part of the stepped line in Figure 1. As long as you cut the price by enough that it’s below the reservation price of these potential customers, you’ll increase the quantity you sell. And as long as you don’t reduce your price below your marginal cost, these extra sales will increase your profits.

Using selective discounts to induce additional sales increases the economic surplus enjoyed both by your business and your customers. You’ll enjoy higher producer surplus because you’re selling at a price above your marginal cost. And the additional sales will generate some consumer surplus because your customers will only be induced to buy your product if the price is at or below their marginal benefit.

The Efficiency of Price Discrimination

Recall from Chapter 14 that when companies exploit their market power to set higher prices, they sell less than the efficient quantity—an outcome we referred to as the underproduction problem. Price discrimination can help solve this problem.

Price discrimination increases the quantity you sell.

That’s because price discrimination includes offering selective discounts to induce additional sales. And indeed, Figure 1 shows that this type of price discrimination leads your business to sell a larger quantity than if you were forced to charge everyone the same price. It follows that price discrimination partly solves the problem of businesses with market power underproducing.

Selective discounts help solve the underproduction problem.

To see why price discrimination helps solve the underproduction problem that otherwise results from market power, it’s worth invoking the marginal principle, and focusing on your marginal revenue. Evaluate the consequences of selling one more item to a marginal customer who wouldn’t otherwise buy your product in these two scenarios:

When You Don’t Price Discriminate

You charge everyone the same price, and so any discount you give to get this extra sale also applies to all of your existing customers. Your marginal revenue is the price you charge that marginal buyer, less the lost revenue from also giving that discount to all your customers. This lost revenue reduces your marginal revenue substantially. In Chapter 14, we called this the “discount effect,” and noted that it causes businesses with market power to underproduce relative to society’s best interests.

When You Price Discriminate

You can be selective about who you offer discounts to. Offer the right discount to the right person—and only that person—and you’ll make a sale you wouldn’t otherwise have made. Your marginal revenue from this extra sale is the price you charge that marginal buyer, which may involve a small discount offered only to that buyer, or perhaps a small number of buyers. The more precisely your price-discriminating strategy targets its discounts, the smaller the discount effect will be, and the less you’ll underproduce relative to what’s in society’s best interest. Indeed, as the example in Figure 1 shows, in the extreme case when you get it exactly right—the case of perfect price discrimination—you’ll keep offering discounts and inducing new customers to buy until the point where your marginal cost is equal to your last customer’s marginal benefit, which means that you’ll produce the efficient quantity. When businesses use selective discounts to increase the quantity they sell, they reduce the underproduction problem.

Interpreting the DATA

Is college tuition really skyrocketing?

Data from: College Board.

There’s a lot of concern that the cost of college is skyrocketing. But is it?

If you focus on the “sticker price” that colleges list on their websites, it looks like it. For instance, the average sticker price at private four-year colleges has nearly doubled from $18,050 in 1990 to $35,830 in 2018. (This comparison adjusts for inflation, and so both of these prices are measured in today’s dollars.) Prices that high would push a lot of students out of college, leading to underproduction of college grads.

But if you focus instead on the “net price”—which is the tuition you pay, minus the scholarships and grants you receive—a different picture emerges. The net price that people pay for college is much lower. And on average, the net price has risen by a much smaller amount, from $12,390 in 1990 to $14,610 in 2018.

What’s really happening is that colleges are now doing a lot more price discrimination. Notably, they are doing more of both parts of a successful price discrimination strategy.

- Part one: Charge higher prices to those who’ll pay them. College administrators understand that wealthy families have high reservation prices, and so they charge them more. To do this, colleges raised the sticker price. In order not to raise prices for other families, they combined these higher sticker prices with offsetting discounts, often known as financial aid, for students from middle-income families, so that their net price has barely risen.

Part two: Offer selective discounts to induce new customers to buy. Colleges have come to understand that they can attract students from low-income families if they make the cost of college extremely low cost or even free. They’ve actually increased the discounts (or grants) they offer these families by even more than enough to offset the rising sticker price. This lower net price for low-income families has led to an increase in the number of low-income students who apply to college.

The result of all this is higher prices for some, lower prices for others, and an increase in the number of applicants, despite little overall change in the average net price actually paid. The student body is probably now stronger because colleges are selecting from a larger pool of applicants. And those selective discounts likely induced people from previously marginalized groups to go to college, creating greater socioeconomic diversity within that student body.

Conditions for Price Discrimination

The extra profits that you can earn through price discrimination suggest that it should be part of the strategic arsenal of any sophisticated manager. But it’s not for everyone. That’s because the whole premise of price discrimination is that you can charge a high price to some folks and a low price to others, and this will only work if three specific conditions are met:

Condition one: Your business has market power.

If your business has no market power—as in a perfectly competitive market—then trying to charge your customers different prices simply won’t work. You could try raising your prices for some customers, but they’ll simply buy from someone else instead. And in perfect competition, you can already sell whatever quantity you want at the prevailing price, so there’s no reason to offer discounts to get new customers. This is why you don’t see price-taking firms like wheat farmers or coal companies trying to price discriminate.

On the flip side, if you do have market power, then price discrimination can help you exploit it, and so it’s well worth considering.

Condition two: You can prevent resale.

Your price-discrimination strategy can only succeed if you find a way to prevent resale. Otherwise, the people who qualify for low prices will buy your product cheaply and then resell it to the folks you were hoping to charge a high price to. If you can’t prevent resale, you’ll end up selling large quantities at the low price—mainly to resellers—and you won’t be able to sell much at the high price because the resellers will undercut you with your high-value customers.

Games are cheaper in Asia, but they may not work in your U.S. PlayStation.

As a result, many companies make it a strategic priority to find new ways to prevent their products being resold. It’s a priority for Sony, which is a major player in both the movie and videogame industries because physical discs—movie DVDs and videogame discs—are easily resold. The ease of resale prevents Sony from charging higher prices to, say, me, an economics professor. If they did, I would avoid paying that higher price by getting a friend who gets lower prices from Sony to purchase my favorite movies or videogames for me. And it’s also the reason Sony won’t offer discounts to financially strapped economics students. Sony is worried that you’ll resell its products on eBay at a profit, undermining its ability to charge other customers higher prices.

Sony is using technology to help solve this problem. For example, it price discriminates partly by charging higher prices in the United States than in India, and it prevents Americans from importing cheap discs from India by including a region code on each disc. That code ensures that a low-priced game or movie bought in India won’t work on a PlayStation or DVD player purchased in the United States. In the future, Sony hopes to do an even better job at preventing resale, and it is trying to shift movie and videogame distribution from sales of discs to online streaming, partly because these online streams can’t be copied or resold.

Other businesses use simpler strategies to prevent resale. Stores sometimes couple their special offers with fine print restricting each customer to buying only two items. This strategy prevents people from stocking up to later resell items they bought on sale. Airlines prevent resale by requiring you show an ID at the airport that matches the name on your ticket. And in the service sector, it’s relatively easy to prevent the resale of services—an hour with your accountant or doctor—because you have to turn up in person for them.

The more aggressively your business price discriminates, the more important it is to prevent resale. This is particularly important for drug companies, which charge around $100 for a year’s worth of AIDS treatment in sub-Saharan Africa, but $10,000 in the United States. That’s why drug company executives worked with the government to make it illegal to import many pills from Africa into the United States. They’re also careful to make the pills they sell overseas a different color or shape, which prevents smugglers from passing them off to U.S. drugstores. These efforts to prevent resale help maintain different prices for different consumers.

Condition three: You can target the right prices to the right customers.

There’s one more challenge: You need to be able to figure out which customers can withstand a higher price and which customers need a discount to buy your product. You could try asking your customers, but they’re usually too smart to admit to a seller that they’re willing to pay higher prices.

Solving this problem of how best to target the right prices to the right customers is central to successful price discrimination. That’s why we’ll spend most of the rest of this chapter developing strategies you can use to target the right prices to the right customers. We’ll start with a simple but familiar strategy, which is to offer different prices to people in identifiably different groups.