17.2 Group Pricing

Next time you go to the movies, I bet you’ll pay a lower price than I do. That’s because most students qualify for a student discount. Movie theaters also charge less for children and seniors. All of this sounds rather civic-minded—as if they’re trying to help those who need it. But it’s actually about the theater boosting its bottom line.

It’s practicing a form of price discrimination known as group pricing, charging different prices to different groups of people. It doesn’t know each customer’s reservation price, so instead, it uses a proxy—whether you’re a student, a child, or a senior—to tailor its prices to different groups of customers.

More generally, group pricing involves offering different prices to groups that differ by their age, location, purchase history, or any other identifiable characteristic. Examples of group pricing include:

- Your campus computer store offers “academic pricing” for Microsoft Office, making it cheaper for students.

- Books are cheaper in India than in the United States.

- Internet companies charge lower prices for residential rather than business service.

- Hairdressers charge more for women’s haircuts than for men’s (even for a similar cut).

- Cell phone companies offer discounts for new customers.

- Microsoft offers lower prices to existing customers by offering upgrades.

- Home Depot and Lowe’s give discounted prices to members of the military.

Indeed, any time your company offers a higher or lower price to one group than to another, you’re engaged in group pricing. But let me offer a hint. Buyers resent being singled out to pay higher prices. So don’t say that your movie theater is charging professors $4 more. Instead, describe your group pricing strategy in terms of group discounts—so that you’re charging students $4 less. The result is obviously the same—those who don’t get the discount pay a higher price than those who do—but you’ll avoid a PR disaster.

EVERYDAY Economics

How to be a savvy online shopper

The rise of online shopping has led to some very sophisticated price-discrimination strategies based on group pricing. For instance, Staples.com has been observed to offer the same stapler at different prices to different groups of customers, depending on the location of their internet connection. While this tactic is controversial, it’s also perfectly legal.

But if you’re a savvy shopper, you can work this to your advantage. Before making a major purchase, try logging on from elsewhere. Or, open your browser in private or incognito mode, which prevents the stores from tracking your movements through their online stores. Another trick: Put something in your shopping cart, but don’t buy it. Some retailers figure this means that you’re in the group of customers with a low enough reservation price that you’re unsure about whether to make a purchase. In many cases, they’ll email you later that week with a discount in order to close the deal.

Setting Group Prices

Group pricing effectively segments what had been one market—say, the market to see movies—into separate markets for each group. It means that your movie theater is now a supplier of a number of different products in a number of different markets: It’s selling tickets in the market for students to see movies, as well as tickets in the separate markets for children, for seniors, and for other adults. In each of these markets, the theater faces different demand curves, and so it sets different prices.

Set the price separately for each group.

It’s time to put yourself in the shoes of the executive team at AMC Theatres. You’ve decided to follow a group-pricing strategy, and now you need to figure out what price to charge each of these groups. You can charge different prices to different groups—so students pay less than other adults—but you charge everyone within a group the same price.

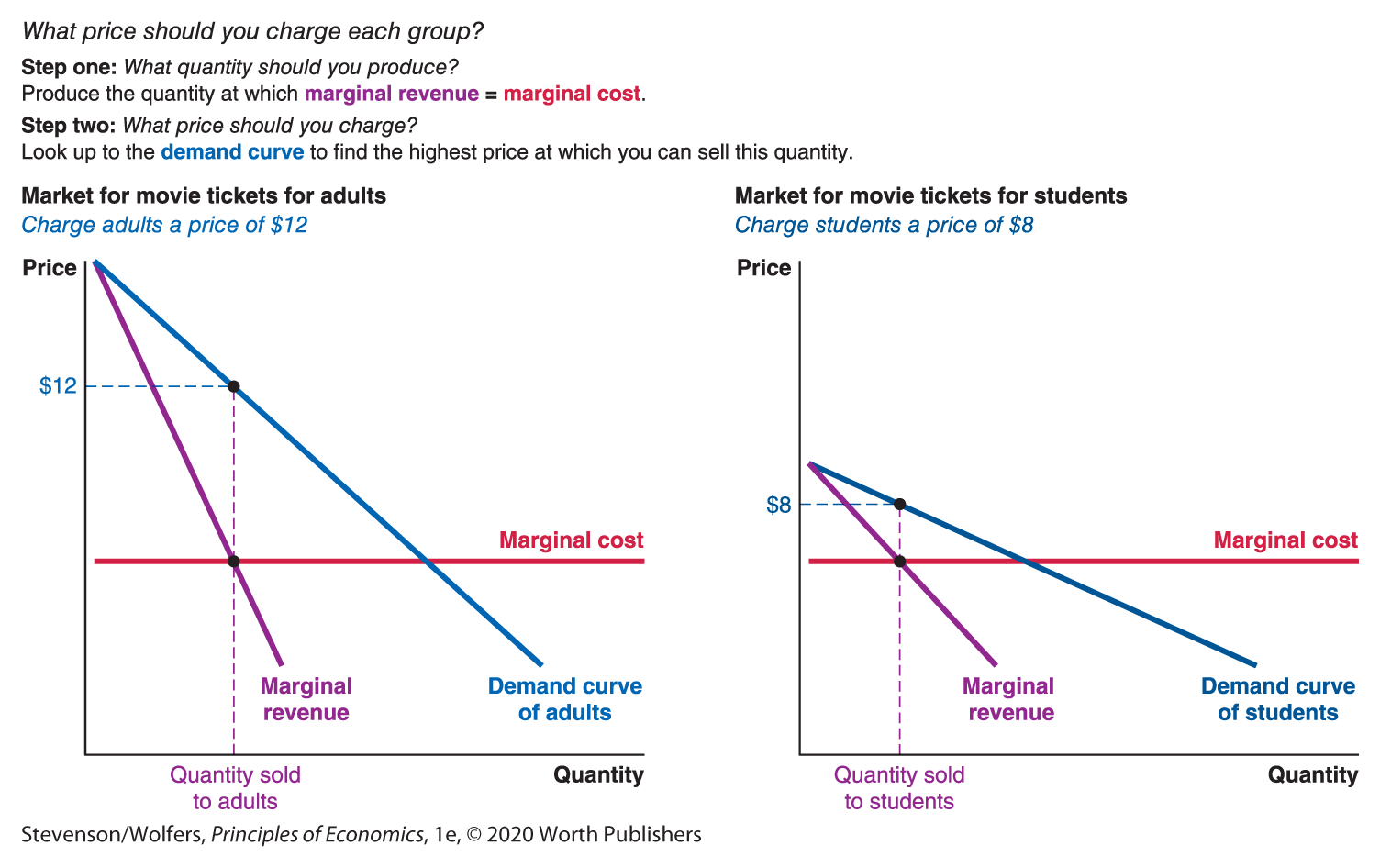

Within each market segment—such as the market for student tickets—you now face a familiar question: What price should you charge students to earn the largest possible profit? And then you face a similar question for adults, kids, and seniors. These are all familiar questions because they’re simply about figuring out the best price to set when you have market power. In each case you should follow the two-step process we explored in Chapter 14:

- Step one: What quantity should you produce? Follow the Rational Rule for Sellers and keep selling until marginal revenue (in that market segment) equals your marginal cost.

- Step two: What price should you charge? Look up to your firm’s demand curve (for that segment) to find the highest price you can set and still sell this quantity.

The demand curves for each group are different, and so you’ll want to follow this two-step process separately for each market segment.

Set different prices for different groups.

Figure 2 illustrates the process for two groups. The left panel shows the market for movie tickets for adults, and the right panel shows the market for movie tickets for students. The demand curve of students is a bit lower because fewer students can afford to pay a lot to see a movie. And it’s flatter because students are more responsive to prices. The two markets are otherwise similar. When you’re engaged in group pricing and there are no spillovers to consider (so adults don’t care how many students are in the theater, and vice versa), each of these is effectively a separate market, which is why you can analyze them separately. Let’s explore how these differences in demand lead theater executives to choose a lower price for students.

Figure 2 | Setting Group Prices

For each group, you should set your quantity at the point where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In each case, your next step is to look up to the demand curve to find the associated price. In this example, the best choice for AMC Theatres is to set the price of movie tickets for adults at $12, and the price for students at $8.

Set prices for each group much as you would set different prices in different markets.

You can analyze each group separately because each group is effectively a separate market. There are two big ideas to keep in mind:

- Charge higher prices to groups that value your product more. This is the idea that the higher the marginal benefit, and hence reservation price, of your customers, the more you’ll be able to get away with charging them a higher price.

- Charge lower prices to groups that are especially price sensitive. This is the idea that market power matters. You don’t have much market power with price-sensitive groups because a small increase in price will lead you to lose a lot of them as customers. And so the more price sensitive a group—that is, the more elastic their demand—the lower the price you’ll want to charge them.

These two ideas explain the pattern of group discounts that many companies offer. For instance, businesses often charge higher prices in the United States than they do overseas because the higher disposable income of American consumers tends to boost their reservation prices. And businesses charge lower prices to students and other price-sensitive groups because they know that they have a lower reservation price.

Interpreting the DATA

Group pricing controversies

It’s not often that a college assignment ignites a corporate controversy, but that’s what happened when Christian Haigh, an economics major, was at his computer doing research for a class called “Data Science to Save the World.” When he clicked on The Princeton Review’s website to look up the price of online SAT tutoring, he noticed that it asked for his zip code. He punched in a few different zip codes, and quickly learned that the company was charging different prices in different parts of the country.

So he and his classmates dug deeper. They coded up a script to harvest the price for all 32,989 zip codes in the United States and found quite large differences. Much of the Northeast paid a high price, parts of California, Texas, Illinois, Wisconsin, Connecticut, and Wyoming paid a medium price, and much of the rest of the country paid a lower price.

It appeared that The Princeton Review was charging higher prices in richer zip codes. Further analysis uncovered a troubling pattern, as areas with a high density of Asian residents were nearly twice as likely to be charged higher prices, even after accounting for the influence of income. This difference may not be the result of intentional discrimination, as these zip codes are also different in other ways. But whether or not it’s intentional, it doesn’t change the fact that, on average, Asian students faced higher prices. The lesson for businesses is that computer algorithms can help them price discriminate, but they may end up doing so in ways that are unpalatable or even illegal. So be careful!

How to Segment Your Market

So far we’ve figured out what price you should charge each group. That’s half of your group pricing strategy. The other half lies in figuring out which groups to target. The main idea is that a successful pricing strategy involves segmenting your market into groups. But how should you do this? There are three criteria that you’ll need to follow to successfully segment your market: find groups with different demand curves, whose membership can be easily verified, and whose membership is difficult to change.

Let’s dig into each of these ideas, in turn.

Criteria one: Segment your market into groups whose demand differs.

The goal of a successful price-discrimination strategy is to set the price you charge each customer as close as possible to their reservation price. And so the idea behind group pricing is to use observable proxies—like being a student—that are related to each customer’s reservation price. The better the proxy—that is, the more closely it captures differences in reservation prices—the more successful your strategy will be.

A movie theater charges a lower price to students because it believes the demand from students is different than that from other adults. Indeed, students typically have lower reservation prices because they have less money to spend, and they’re also likely to be more price sensitive. Because of these demand differences, it’s more profitable to charge a lower price to students than other adults.

But notice that no theater charges different prices for men and women. Partly, that’s to avoid stoking public outrage. But it’s also partly about economics. Men and women have fairly similar demand for movies, and so a buyer’s gender is not a useful proxy for their reservation price. There’s no point in segmenting your market into groups whose demand doesn’t differ.

How far should you segment your market? It depends on what information you have available to you. Movie theaters don’t know much about their customers—basically just whether they have a student card or a senior card in their wallets. As a result, they follow a fairly coarse market segmentation, charging different prices to just a few different groups. By contrast, colleges know a lot more about their students, so they use much more fine-grained segmentation, tailoring their financial aid packages to each individual student’s circumstances. A typical college segments the market by family income, home ownership, savings, family size and structure, state residency, and many other variables. All of this information helps tailor the net price of college much more closely to each household’s reservation price.

In deciding which segments to offer group-specific prices to, your goal should be to find the cleavages that best divide your market into segments with distinct patterns of demand.

Interpreting the DATA

Why the same drugs cost less for Fido than for Freddy

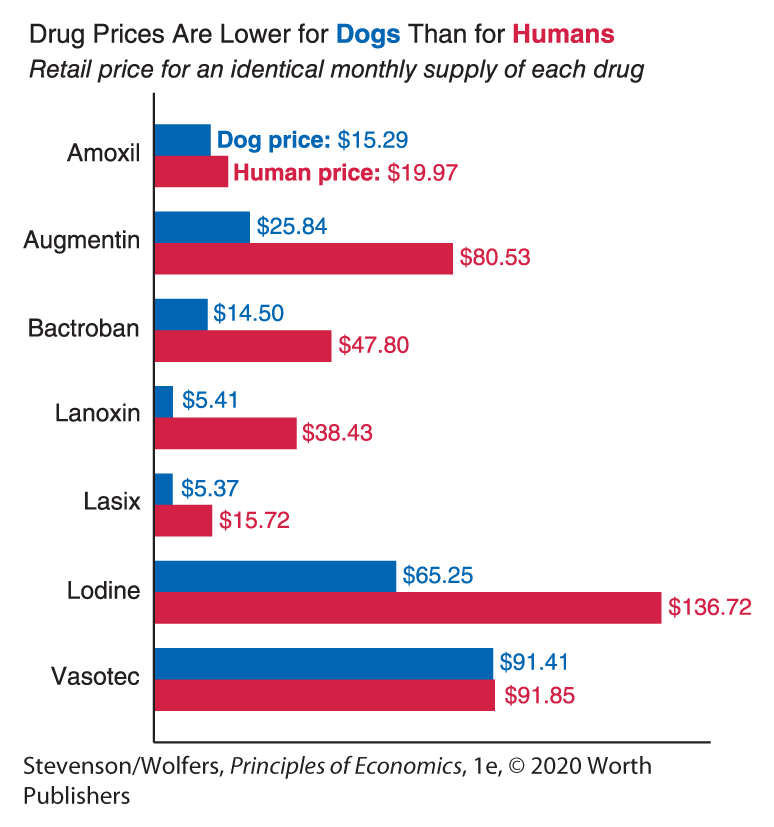

Data from: “Prescription Drug Price Discrimination in the 5th Congressional District in Florida.”

You might be surprised to learn that humans and dogs often take the same medications. In some cases, they’re identical—they use the same active ingredients, meet the same FDA rules for quality and purity, and are often made in the same factory by the same drug company. The key difference between the dog and human versions is that people fill their prescriptions at a retail pharmacy, while dogs fill their prescriptions at a veterinary pharmacy.

A study that examined eight of these dog-and-human medications found that the human pharmacy typically charged a price that was around twice as high as the veterinary pharmacy. It’s a simple case of price discrimination—charging different species different prices for the exact same drug. This price differential is targeted to differences in reservation prices, suggesting that people care more about their own health than that of their four-legged friends. Woof!

Criteria two: Target your group discounts based on verifiable characteristics.

When you offer different groups different prices, you’ll quickly discover that buyers will try to come up with cunning ways to avoid paying the high price. That’s why it’s important to link your group discounts to verifiable characteristics, such as your customer’s age, student status, or address. This ensures that people can’t just lie about their status to get the discount.

The characteristics that are verifiable vary a bit, depending on your industry. A movie theater can verify whether a customer is a student by asking to see their student ID. But an online retailer can’t do this. Instead, many websites offer discounts to folks with email addresses that end in “.edu.” (Your professors love this because it means they also qualify for student discounts!)

Very few businesses can verify their customers’ incomes, which explains why it’s rare to see discounts based on your income or wealth. Colleges are a notable exception, as they tailor their financial aid offers to your family’s income. They can do this because the government helps them verify your family’s income. When you fill out the FAFSA, you give the government permission to share your tax records with the colleges of your choice.

Criteria three: Base group discounts on difficult-to-change characteristics.

Finally, you should segment your market based on characteristics that are not only verifiable, but also difficult to change. This is to avoid the possibility that your customers will switch into a different group in order to get a lower price.

Discounts for children pass this test, because people can typically tell whether you are actually a child. Student discounts sort of pass this test, since it’s pretty unlikely someone would start attending college just to get $4 off the price of movie tickets. But if too many people start using their old student IDs to get discounts not meant for them, then it would no longer pass this test.

While most people think it’s wrong to lie outright to get a discount, economists have also found that any changeable characteristic appears to be on the rise whenever there is a discount to be had. So if the movie theater starts offering discounts to people with vision problems, you’ll see a lot more people show up wearing glasses.

EVERYDAY Economics

Pay less for graduate school

In-state tuition is a form of group discount, but it’s based on a characteristic that’s not too difficult to change—your official state of residence. Know the rules about this, and you could save a ton of money. For instance, the University of California system—which includes many top business, law, and medical schools as well as top-tier doctoral programs—allows you to become an official California resident once you’ve been in the state for a year, as long as you meet certain eligibility requirements and fill in the appropriate paperwork. That means that even if you’re not from California, you may qualify for in-state tuition by the time of your second year of graduate school. The rules differ across states, but it’s worth checking them out.

Recap: Group discounts are a promising price-discrimination strategy.

Group pricing can be an effective price-discrimination strategy when verifiable and hard-to-change factors like a customer’s home address do a good job in sorting out which buyers have high reservation prices.

But what should you do when observable characteristics aren’t a good proxy for your customers’ reservation prices? Answering this is our next task, and we’ll explore an approach to price discrimination that doesn’t require you to know anything at all about your customers’ characteristics.