18.1 How to Think Strategically

One of these involves game theory.

The other does not.

Think of the difference between a boxing bag and a boxer. To hit a punching bag, you line it up, take your swing—and boom!—you’ve walloped it. But hitting a boxer is much harder: A boxer will duck and weave, feint one way and move the other, raise their gloves to deflect the blow, or counterpunch. The boxing bag is not strategic; a boxer is strategic—a boxer anticipates, responds, and tries to influence your movements. When two boxers meet, the outcome is determined not only by their skill and strength, but also by the interaction of their competing strategies.

When you’re meeting with business partners, political rivals, friends, or romantic partners, you need to figure out whether they’re more like a boxing bag or a boxer. If they’re more like the boxer, then you’re in the realm of game theory. And you’re going to need to learn to think like a game theorist in order to avoid getting knocked out.

Introducing Game Theory

Game theory is the science of making good decisions in situations involving strategic interactions, which means that your best choice may depend on what other people choose, and likewise, their best choices may depend on what you choose. Your best choice might depend as much on the choices made by your allies as your opponents, and hence this notion of strategic interactions encompasses collaboration as much as competition.

Game theory gets its name from the observation that the same notions that inform how you might box or play a strategic game like chess, can also be applied to your business strategies, and indeed, the many strategic interactions that arise in the ordinary business of life. The underlying idea comes from applying the interdependence principle, focusing on how your decisions are intertwined with those of others. It might seem a bit unusual to call these interactions “games,” but pretty soon you’ll see people “playing games”—sometimes high-stakes games—all around you.

Storytelling and metaphors will help you learn game theory.

As we explore the science of strategic interactions, we’ll work through a series of stories. You shouldn’t take each story too seriously, but rather look to see how each highlights a deeper logic that applies much more broadly. Think of each story as a metaphor. Your task is to discover all the different ways that these metaphors apply to your interactions with others. As you get better at this, you’ll find yourself applying game theoretic insights to everything from your business decisions to your dating life.

Games are strategic interactions—and they’re all around you.

Strategic interactions are central to your economic and social life. For instance, in business you’ll have strategic interactions (that is, you’ll “play games”) with your competitors, particularly in an oligopoly where you have only a few rivals. Business decisions are strategic interactions because the payoff to, say, cutting your prices, depends on whether your competitors respond with a similar price cut. Likewise, your decision on how best to position your product is a strategic interaction because the profitability of targeting a particular market segment depends on how your competitors position their products. And your decision to enter a new market involves a strategic interaction, because your profitability depends on whether the incumbent firms will respond with a price war. Strategic interactions include partners as well as rivals, and the profitability of a new investment might depend on how much your partners invest in the project.

Politics is full of game theory. There are strategic interactions between both political rivals and political allies, because the payoff from voting for a bill depends on whether others vote for it, too. In elections you might choose to vote only if other voters are likely to make it a close election. There are also weighty strategic interactions when countries decide to get involved in an arms race or amass troops near the border.

Strategic interactions also occur among friends. These interactions highlight that sometimes strategy is more about cooperation and coordination rather than competition. For instance, a party is more fun if your friends are going to it too. So it’s natural that your decision about whether to go a party will depend on what you think your friends will do.

Hopefully this gives you a sense that strategic interactions—games—are a pervasive part of your life. And though they are all different, there’s a basic logic that is common to all strategic interactions—making a good choice requires that you anticipate what others will do. This is why our next task is to develop some intuitions that will help you make good decisions in all of the games you play.

The Four Steps for Making Good Strategic Decisions

Making good strategic decisions boils down to following four simple steps. Savvy strategists internalize these ways of thinking so that they become mental habits. That should be your goal too. We’ll start by learning the four steps now, and then we’ll turn to some specific games to see how these habits will help you uncover deeper strategic insights.

Step one: Consider all the possible outcomes.

To make an informed choice, you’ll need to consider all the different outcomes that could occur. This means considering every combination of choices that both you and other players might make.

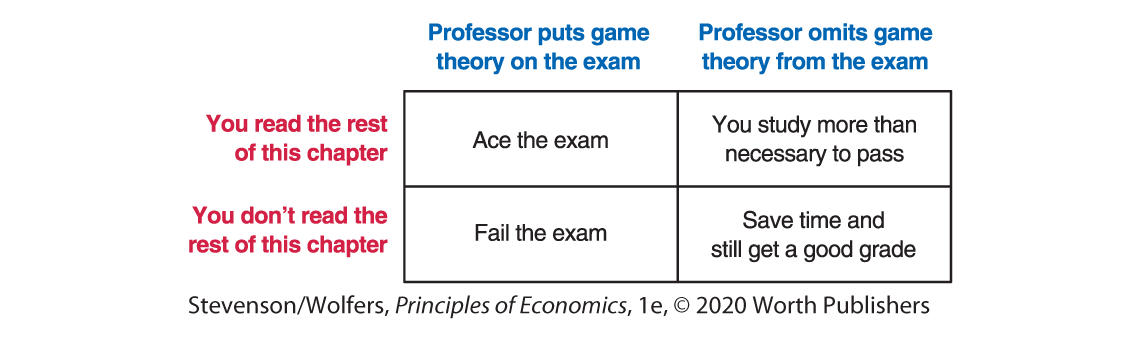

There’s a simple trick for listing all the possible outcomes in a two-player game: Construct a table that lists each of your possible actions as a separate row, and each of the other player’s possible actions as a separate column. The cells in this table now show all the possible outcomes. Because we usually list the payoffs to both players in each cell, we call this a payoff table. For instance, you have two choices right now: Keep reading this chapter, or not. And your professor has two choices: Put game theory on the exam, or not. We can summarize the possible outcomes as follows:

Figure 1 describes different payoffs in words (“You ace the exam”). In most cases though, we’ll use numbers such as your grades, your business’s profit, or some other measure of your payoff from each outcome.

Figure 1 | A Payoff Table

Step two: Think about the “what ifs” separately.

Once you start thinking about strategic interactions, you can easily get overwhelmed by the complexity of it all. For instance, whether you read the rest of this chapter partly depends on whether you think your professor will put game theory on the exam. And whether she puts game theory on the exam depends on whether she expects you to read the rest of this chapter. And so your choice depends on what you expect her to choose, and you know that her choice depends on what she expects you to choose. Keep thinking this way and pretty quickly you will disappear down the rabbit hole of “I think that she thinks that I think that she thinks . . .” Let me help you out of that rabbit hole by showing you a simpler way.

Here’s the idea: Break the problem into its simpler components, which are the various choices that the other person could make. Think in terms of “what ifs?” and write down each “what if?” separately. In this case, you want to ask: What if she does include game theory on the exam? And what if she doesn’t? When you think about these separately, you get two far simpler problems. You’ll then proceed to the next step.

Step three: Play your best response.

For each “what if?” your goal should be to play your best response—the choice that yields the highest possible payoff for you, given the other player’s choice. What is your best response if your professor does include game theory on the exam? (Probably to keep reading this chapter.) And what is your best response if she doesn’t? (I would say keep reading because game theory is useful, but if all you care about is your exam grade, then you can stop now.)

There’s one more thing I want you to do: When you find your best response, put a check mark next to it. This check mark will help you remember your best response, and it’ll be part of a useful trick that we’ll get to shortly.

Step four: Put yourself in someone else’s shoes.

In every strategic interaction your outcomes depend on the choices that other people make. This means that you cannot figure out your best choice without first trying to figure out the choices that others will make. To figure out someone else’s choices you need to apply the someone else’s shoes technique from Chapter 1. This technique tells you to put yourself in someone else’s shoes in order to figure out what decision you would make if you faced their incentives.

She’s thinking strategically.

When you put yourself in your opponent’s shoes, you’ll often come to see that they are also thinking strategically. Just as you do, they’ll consider all the possible outcomes, think through the various “what ifs,” and evaluate their best responses. When you work your way through someone else’s thought process, you’ll find it easier to predict their choices. For instance, put yourself in your professor’s shoes: When she writes an exam, she wants to make sure that she rewards students who read all the material. Understanding this, you realize that it’s a good idea to keep reading to the end of this chapter.

Now armed with these four steps for thinking about strategic interactions, let’s start applying them to some specific games. We’ll begin with the most famous example in game theory, the Prisoner’s Dilemma.