20.1 Adverse Selection When Sellers Know More Than Buyers

How do you know who’s telling the truth? You might ask your auto mechanic if he’s honest, and if he is, he’ll say, “Yes.” But if he’s not, he’s still probably going to say, “Yes.” When the person you’re buying a good or service from has information that you don’t have, it can be hard to figure out whether to do business with them. Private information arises when one party in a transaction knows something the other doesn’t. (It’s sometimes called asymmetric information, because your private information creates an asymmetry between you and them.) In this section, we’ll focus on problems that arise when sellers have private information about the quality of their goods. As a buyer in these situations, you’ll need to be careful not to get ripped off.

Of course I’m a prince!

Hidden Quality and the Risk of Getting a Lemon

If you’ve ever bought a used car, you’ve probably wondered what the seller knows about the car—its defects, history, and reliability—that you don’t. Buying a used car is risky because you don’t know if you’re being sold a lemon—a hunk of junk that’ll end up having one problem after another. Unfortunately, it’s hard to learn about these problems without spending a lot of time with the car.

The problem with buying a used car is that sellers have private information. They’ve learned from experience whether they have a lemon. They know whether their car breaks down regularly and whether they drove it in ways that can lead to costly maintenance down the line—like braking or accelerating too rapidly.

As a buyer, you don’t have this information. You can’t tell whether the car you’re looking at is a lemon or not. But you do know there’s a risk it’s a lemon. That’s why the amount that buyers are willing to pay for a used car is lower than if they could be sure that it’s of high quality. When buyers can’t tell the difference between lemons and high-quality cars, both lemons and high-quality cars will sell for the same price. After all, if buyers can’t tell the difference how can sellers charge different prices? In turn, this means that lemons will sell for more than they would if buyers could tell them apart, and high-quality cars will sell for less than they would if their buyers could discern their quality.

Is it a lemon?

The amount that buyers are willing to pay for cars of unknown quality also affects what kinds of cars sellers will offer for sale. To see how let’s fast forward a couple of years to explore the types of decisions you might make as a potential seller in the used-car market.

Sellers of high-quality goods may choose to not sell.

Perhaps, after you graduate, you get a job in an urban area with good public transportation. You don’t need a car to get to work and moving your car across the country will be costly. You wonder if you should sell your car. Importantly, you know that it’s in excellent condition and that you’ve taken great care of it. But when you go to sell it, buyers can’t tell that it’s not a lemon. As a result, they’ll offer you a low price for your car. You compare the price you can get for it, with its alternative value to you. A road trip to your new city sounds fun, and while you don’t need a car, it would be convenient. When you compare the benefit to you of having a high-quality car with the small amount you can get by selling it, you decide to keep the car. When potential sellers like you—folks looking to offload a high-quality car—decide not to sell because they can’t get a price high enough to offset what the car is worth to them, there are fewer high-quality cars offered in the used-car market.

Sellers of lemons are more likely to sell.

Now consider the same scenario, except this time consider the choice you’ll make if you know that your car is a lemon. It burns through oil and you can feel the transmission slipping from time to time. This car’s not worth much to you—you don’t trust it to drive across the country to your new location and you figure that you’ll spend more time keeping it running than using it to do errands. When you go to sell it, buyers can’t tell that it’s a lemon. When they ask you why you’re selling, you’ll probably tell them that you’re moving for a new job and don’t need a car anymore. After all, these things are true! And while you know that you should, you don’t mention that it’s a lemon, perhaps convincing yourself that maybe it’ll be ok for the next buyer.

Buyers aren’t sure whether your car is high-quality or a lemon, but it could be high quality, so they’ll offer more than they would pay if they knew it was a lemon for sure. You think these offers are great—after all, you’re offloading a lemon! That means that the price they are willing to pay is above what the car is worth to you, so you accept the offer. When sellers like you—folks looking to offload an unreliable car—decide to sell because the price is higher than the value of a lemon, there will be more lemons available in the used-car market.

Adverse selection of sellers can cause the market to collapse.

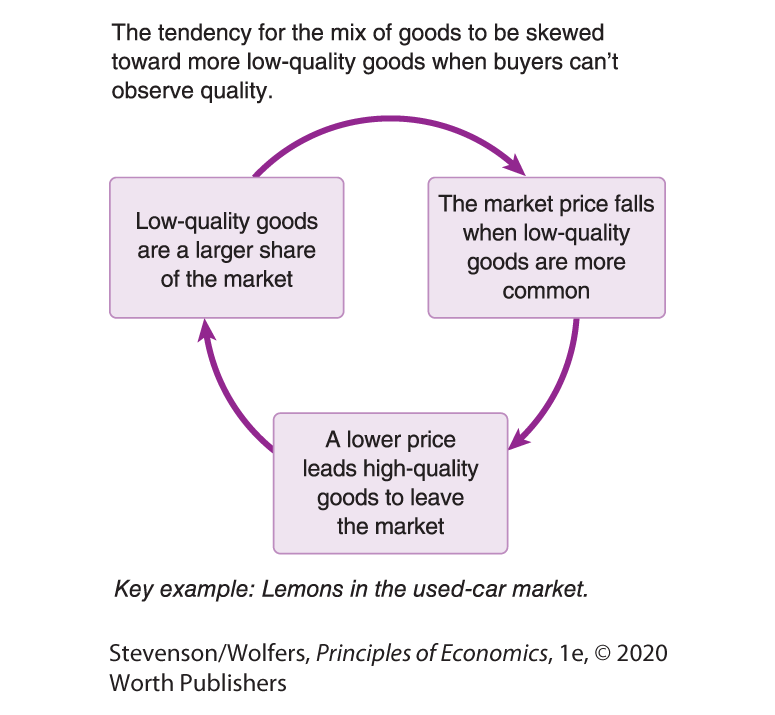

Putting these two insights together—that owners of lemons get a high price compared to what the car is actually worth, and owners of high-quality cars get a low price compared to what the car is actually worth—means that lemons are more likely to be offered for sale in the used-car market than there would be if everyone had the same information. As a result, you’re more likely to encounter a lemon at a used-car dealership than in an ordinary parking lot. This is known as adverse selection of sellers—the tendency for the mix of goods offered for sale to be skewed toward more low-quality goods when buyers can’t observe quality. It’s selection because the sellers get to choose what’s offered for sale, and it’s adverse because they’re more likely to offer low-quality goods.

Figure 1 highlights the problem with adverse selection of sellers. The risk of buying low-quality goods reduces the price that buyers will pay, this lower market price leads sellers to offer fewer high-quality goods, which means that the mix of goods sold includes more low-quality goods. And these effects are self-reinforcing, as the fact that low-quality goods are a higher share of the market drives the price down even further, which causes more high-quality goods to exit.

Figure 1 | Adverse Selection of Sellers

This is sometimes called the adverse selection death spiral, because this cycle can continue until there’s nothing left in the market but low-quality goods. When that happens the market price will be the price for lemons, and only lemons will be sold. For example, how many real Rolexes or Coach bags do you think are sold by vendors on the streets of New York City? Knockoffs are so prevalent that buyers are only willing to pay prices so low that no seller would supply authentic merchandise. It’s a market for fakes only.

Do the Economics

To see how all this works, let’s analyze the used-car market in a bit more detail. We’ll see how the prices buyers are willing to pay help determine which cars get sold, and how that then feeds back into the prices that buyers are willing to pay.

Let’s start with the buyers. In this example, let’s say that buyers value lemons at $2,000, they value good cars at $12,000, and buyers are risk-neutral (which means they’re indifferent to risk).

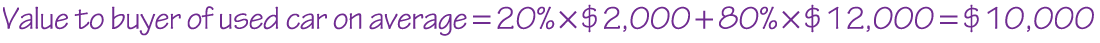

- What price will buyers be willing to pay if 20% of the cars offered for sale are lemons?

Start by figuring out the value of a used car on average. Since 20% are lemons, and those cars are worth $2,000 to buyers, while 80% are high-quality cars they value at $12,000:

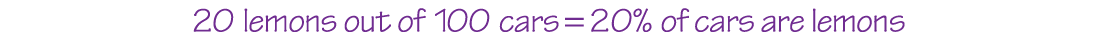

Now let’s consider the sellers. 100 people are considering selling their cars. 20 have lemons, which they would sell for as little as $2,000. 30 have a high-quality car that they need to sell, so they’d sell it if offered at least $5,000. (At lower prices, they’ll decide to give it to a relative instead.) And 50 have a high-quality car but they don’t really need to sell their car, so they’ll sell it only if they’re offered a price of at least $11,000.

- What share of all used cars are lemons?

- If buyers are willing to pay $10,000 for a used car, as we found above, what fraction of cars offered for sale will be lemons?

There will be 20 sellers of lemons, and 30 sellers who have a high-quality car that they need to sell. (The other 50 people with high-quality cars will choose not to sell since the price is less than the $11,000 needed to induce them to sell.)

Let’s see how buyers will respond.

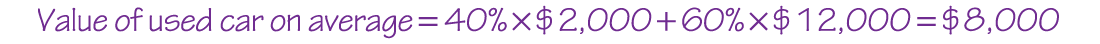

- If 40% of cars offered for sale are lemons, what price will risk-neutral buyers be willing to pay for a used car?

At this price the used-car market stabilizes with buyers willing to pay up to $8,000 and 40% of the cars offered for sale are lemons.

- Extension: What if 75% of all used cars are lemons, what will happen?

Buyers: Value of used car on average = 75%×$2,000+25%×$12,000=$4,500

Sellers: Only sellers of lemons will offer their car for sale.

Buyer response: If 100% of cars are lemons, price=$2,000

In the first example, the market stabilizes at a price of $8,000 which is lower than the value of the average used car. Lemons are overrepresented among the used cars offered for sale, but some high-quality cars are still sold. However, in the extension the large number of lemons ends up driving all the high-quality cars out of the market. Since buyers can’t distinguish between lemons and high-quality cars, the used-car market collapses, and the only cars sold are lemons.

EVERYDAY Economics

Why you should consider buying a used car from a relative or friend

It may not be cool, but at least you know it’s not a lemon.

The problem with the used-car market is that you can’t sell a high-quality used car for what it’s actually worth. That means that if a family member or close friend—indeed, anyone you can trust—is thinking of selling their car, you can get a great deal. Even if you pay your sister more than the prevailing price in the used-car market, you benefit from knowing that she would likely tell you the truth if the car was a lemon. This is why used cars are often kept in the family or sold to friends. These sales benefit both sides: If you buy from your sister, she can charge you a fair price given the condition of the car; and you get the comfort of knowing you’re driving a reliable car. Buying from people you trust solves the lemons problem.

Adverse Selection and Your Ability to Buy High-Quality Products

So far we’ve seen that when quality is hard to observe, sellers are more likely to supply goods they know to be of lower quality. This in turn reduces the price that buyers are willing to pay, which leads more sellers of high-quality goods to leave the market.

The result is a market failure in which the forces of supply and demand lead to an inefficient outcome. The failure is that many people will be unable to buy or sell some products—particularly high-quality products—even when the marginal benefit to buyers of purchasing a high-quality product exceeds the marginal cost to sellers of supplying it. There are buyers who would benefit if they could find a reliable seller of high-quality products, and they’re willing to pay a good price for one. Sellers of high-quality products would also benefit if they could find a buyer willing to pay a good price for their product. But they won’t be able to sell them at a price that reflects their products’ high-quality, because buyers can’t tell that they’re not getting a lemon. That makes buyers reluctant to pay the high price needed to get a high-quality product. Buyers are right to be worried because suppliers can trick them into buying a lemon. The problem is that buyers can’t be sure they’ll get the right product. When sellers know more than buyers about quality, mistrust makes the market function poorly, leading it to fail to work for many buyers and sellers.

Adverse selection problems can arise whenever sellers have private information.

The lemons problem is not just about used cars. It can occur whenever there’s an information gap in which sellers know more than buyers. As a buyer, you’ll need to watch out for adverse selection problems so that you know what you’re getting. Here are a few real-world examples:

- You want to buy a Tiffany necklace online, but how do you know if it’s a fake? eBay shoppers demand a discount because they suspect some necklaces are fakes, but this discounted price makes those with authentic Tiffany necklaces reluctant to sell. As a result fakes become relatively more prevalent, which explains why Tiffany discovered 70% of its products for sale on eBay were fake.

- You want to buy health supplements, but how do you know what’s really in the capsules? Suppliers who use cheap fillers instead of promised ingredients will be more profitable at lower prices, shifting the mix of sellers toward those with fake products. Indeed, when the New York attorney general’s office tested many herbal supplements, it found four out of five didn’t contain the promised ingredients, and many were filled with cheap fillers like ground-up house plants.

Can you tell which one is wild salmon?

- You want to buy wild salmon, but how do you know if the fish is wild or if it’s even salmon? Since consumers can’t tell when cheaper fish are masquerading as more expensive fish, imposters are offered for sale, but that drives down prices. Low prices then make it harder for fishing vessels to profitably supply genuine wild salmon. Oceana, an advocacy group, tested DNA on over 1,000 seafood samples from hundreds of retail outlets across the country and found that a third weren’t what they said they were.

- You may want to invest your money by buying shares in a company. But be careful: Corporate executives are more willing to issue new shares when they believe their company’s share price is overvalued. Since buyers tend to know less than the company’s executives, they have a hard time telling if this stock is overvalued. This drives down the price buyers are willing to pay. These low prices discourage undervalued or correctly valued companies from issuing shares. As a result, new stock issues are disproportionately made up of overvalued companies.

The problem in each of these situations isn’t simply that some products are higher quality than others—it’s that buyers can’t accurately evaluate quality when they make their purchase, but sellers can. This reduces how much buyers are willing to pay, which drives out some high-quality sellers, leaving a larger share of low-quality sellers. If the adverse selection problem is bad enough, the market will consist of only suppliers of low-quality products.

But the website said this was a nice hotel.

Be skeptical, especially when the price seems too good to be true.

As a buyer, you won’t always know how many low-quality sellers there are. Many people use price as an indicator of the likely quality. When a price seems too good to be true, it probably is! Low prices are often an indicator that there are a lot of low-quality goods and services in the market. But be careful: A high price doesn’t mean something is high quality. If choosing a high price made you think that something was high quality, then sellers of low-quality goods would simply set a high price to try to fool you. You can’t trust a price to tell you about quality when it’s otherwise unobservable.

Solutions to Adverse Selection of Sellers

Thankfully, there are ways to address the adverse selection problems that can arise when sellers have private information. When you’re a seller, these solutions can help you provide better information that can make buyers more comfortable buying your product. And when you’re a buyer, these solutions can help you tell high- and low-quality products apart.

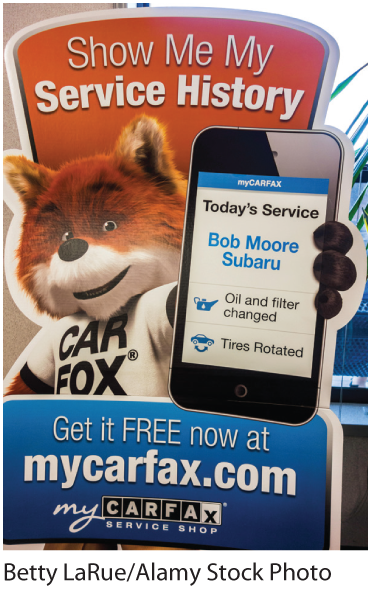

Solution one: Buyers can learn from third-party verifiers.

Third-party verifiers can help you spot a lemon.

As we’ve seen, an information gap can be costly to both buyers and sellers. This points to a business opportunity for savvy entrepreneurs to try to bridge that gap. For example, Carfax is a web-based company that checks tens of thousands of sources to learn a car’s ownership history, maintenance records, and whether a car has ever been in an accident. While it would be difficult for an individual buyer to do this on their own, a trusted independent third party like Carfax can help solve adverse selection problems by reliably and efficiently gathering and sharing that information. This is an example of a business operating as a third-party verifier, reducing the amount of private information held only by sellers. Third-party verifiers gather credible information and make it available to potential buyers, thereby making it easier for them to identify high-quality products.

Third-party verifiers can help shoppers learn about the quality of products.

Your mechanic is another resource—a third-party verifier—who can give you expert information about the current state of a car you’re thinking of buying. When you’re buying a used car, it’s a good idea to do both—check a third-party report like Carfax and get it inspected by your mechanic.

Third-party verifiers exist for many goods. Consumer Reports tests products and reports on their quality, giving information about the reliability of everything from bike helmets to kitchen sinks. U.S. News & World Report ranks colleges and universities using data that would be difficult for prospective students to gather on their own. Moody’s rates the creditworthiness of companies looking to borrow money, so you know which corporate bonds are safest.

Other organizations provide certifications that reveal useful information about workers in professional services. For instance, if you want to find a financial advisor who’s knowledgeable and has your best interests at heart, then you can look to the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors, who certify only highly trained financial advisers who commit to not taking any kickbacks for recommending specific investments.

Third-party verifiers can help shoppers learn about the experiences of past customers.

Some third-party verifiers aggregate the experience of past customers. The internet has made it easier for you to share your experiences, and many companies are using it to help buyers figure out which sellers offer high-quality goods and services. Companies like Angie’s List, Yelp, TripAdvisor, and Amazon provide customer ratings and reviews of products and services. Anytime you’re considering a major purchase, it might also be worth consulting a website called The Wirecutter, which aggregates reviews from many different sources. When potential buyers have easy access to the experiences of past customers, there’s a stronger incentive to treat your customers well, because a reputation for providing shoddy products will quickly catch up with you.

Don’t say you weren’t warned.

Solution two: Sellers can signal their product’s quality.

Actions speak louder than words, particularly when there’s private information. Sellers can’t simply tell you about how great their products are, because why should you believe them? But sometimes they can reveal their private information by taking an action. A signal is an action taken to credibly convey private information. In Chapter 12 we analyzed how education can be a useful way for workers to credibly signal to employers that they are capable and tenacious workers. Private information is a problem in the labor market because workers (who are sellers of labor) know how capable and tenacious they are, but buyers (that is, employers) don’t. An employer can’t figure this out just by asking, because no one in a job interview ever responds by saying “thanks for asking, because really, I’m neither capable nor tenacious.” So employers rely instead on actions—like earning a degree—which signal that information.

There are all sorts of signals that sellers can use to convey their true quality. A useful signal helps you differentiate good products from bad ones. However, in order for a signal to work, it must be substantially costlier for sellers of low-quality products to send the signal than for sellers of high-quality goods to do so. That way, only the high-quality sellers will choose to send the signal.

For example, a car dealer who wants to signal that they’re selling high-quality used cars, will offer a warranty—paying for any needed repairs for the first few years after the purchase. Such a warranty is costlier for people selling lemons. If offering a warranty is too costly for those with lemons to offer, then high-quality used cars might come with warranties, while lemons won’t. For similar reasons, a person trying to sell you their high-quality used car might show you maintenance records, offer to pay for a mechanic’s inspection, and give you a Carfax report.

Signals like this help buyers discern whether they’re being offered lemons or high-quality products. They’re reliable only when sellers of high-quality products are much more likely to find it worthwhile to send the signal. This will lead to a price difference between those products in which the seller credibly signals high-quality and those in which the seller doesn’t. For example, cars with warranties sell for more than cars without. Importantly, this price difference reflects not just the value of the warranty, but also the fact that the warranty signals to buyers that this is a high-quality car. As long as it’s too expensive for an owner of a lemon to offer the warranty, then presence or absence of a warranty effectively tells you whether you’re considering a high-quality used car or a lemon.

Solution three: Government can increase information or weed out low-quality goods.

Government policy can help in three ways. The first is by providing information directly to buyers; the second is by giving sellers an incentive to reveal truthful information, and the third is by regulating quality, and therefore keeping sellers of the lowest-quality products out of the market.

Government reveals information.

Have you ever wondered if it was worth it to buy organic produce? Before you answer, think about whether you can tell whether the “organic” produce you’re being sold is actually grown organically. For many years it was virtually impossible. But then the U.S. Department of Agriculture created regulations that define what it means to be organic and what farmers need to do to be able to apply the label organic. Now, when you see the government’s official organic seal, you know what you’re getting.

Government creates incentives for sellers to reveal private information.

The government can also help close the information gap between buyers and sellers by giving sellers an incentive to reveal what they know. For instance, when you sell your house, the law requires you to reveal any problems that you’re aware of—such as a roof that needs to be replaced or asbestos that needs to be removed. In some states, sellers must also disclose more unusual problems, like a history of death in the house or a reputation as a haunted house. The idea isn’t to take a stance on whether ghosts exist, but rather to require homeowners to disclose any information that might affect a buyer’s willingness to pay.

Would you want to buy a house with a chilling past?

Government can outlaw the lowest-quality product.

There may be situations where it’s best to simply eliminate low-quality sellers. For instance, you probably don’t want a doctor who doesn’t know anything about medicine. That’s why many types of jobs—including medicine—require an occupational license in order to ensure a minimum quality of service. Similarly, federal and state agencies like the Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission set minimum quality levels for some products, with the aim of effectively eliminating low-quality products from the market. If suppliers aren’t allowed to sell low-quality products, then their private information, and hence the problem of adverse selection, disappears.