23.3 Understanding Unemployment

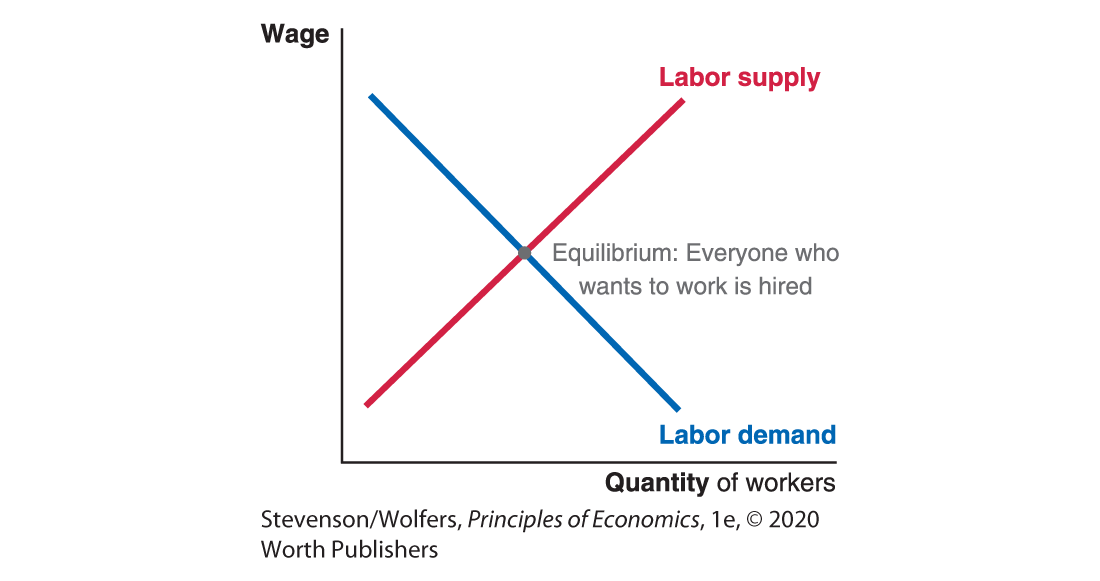

Now that we’ve explored the labor market and discovered how to measure unemployment, it’s time to dig into what causes unemployment. The starting point is supply and demand in the market for labor. Workers supply their labor, selling it for a price (their wage). Like other markets, supply is upward-sloping, meaning that workers supply more labor when wages are high. Employers—buyers of labor—demand less when the price of labor is high, so they hire fewer people when wages are high.

If market forces worked perfectly, wages would adjust to the point where the quantity of labor demanded is equal to the quantity of labor supplied as shown in Figure 9. The forces of supply and demand would ensure that everyone who wanted to work at wages that employers were willing to pay would find jobs. That’s because workers who wanted a job but couldn’t find one would be willing to work for a bit less, pushing wages down so that employers would hire more people, and fewer people would want jobs. This process means no one is left unemployed—willing to work at market wages, but unable to find a job.

Figure 9 | Labor Demand Equals Labor Supply

Types of Unemployment

Unemployment reflects the failure of the market to bring the demand for labor in balance with its supply. Why does this happen? There are three categories of reasons that people experience unemployment. Let’s start by learning what the three categories are.

Unemployment type one: Frictional unemployment.

Frictional unemployment occurs because it takes time for employers to search for workers and for workers to search for jobs. Labor demand and labor supply might be in balance—in other words, there might be enough jobs for all the people who want them—but the process of matching workers and jobs isn’t instantaneous. When you graduate from college with an economics degree there is a good job out there for you, but you’ll still spend time talking to employers, going on interviews, and trying to figure out which job has the right mix of tasks, co-workers, benefits, and perks that will make it the best fit for you. You may even need to relocate to where your skills are most in demand by employers.

Unemployment type two: Structural unemployment.

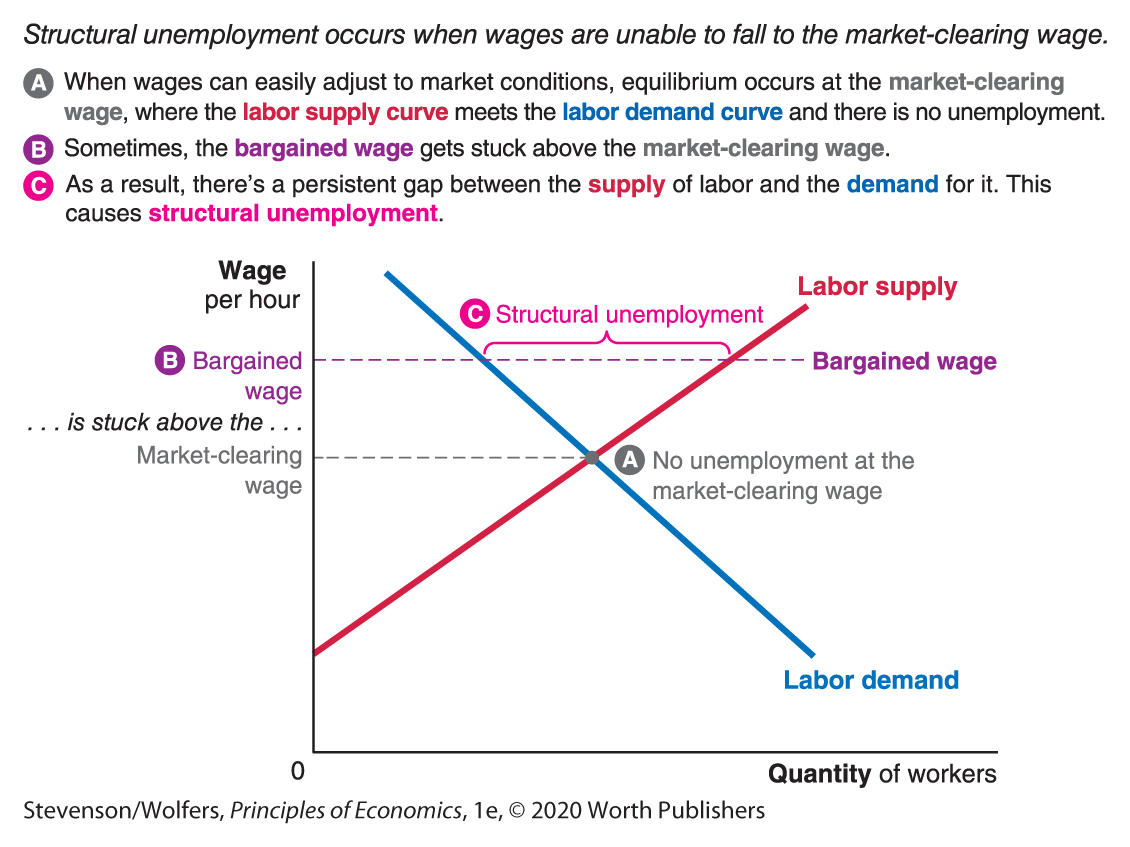

Structural unemployment occurs when there are structural barriers that prevent wages from falling to the point where labor demand and labor supply are in equilibrium. Because wages remain higher than the equilibrium level, more workers want to work, but employers offer fewer jobs. There are many reasons that this happens: Employers sometimes want to pay higher wages to get more effort out of workers; unions may push for higher wages; and governments may enact policies that make it hard for the labor market to clear. These features of the labor market can lead to unemployment, and we’ll explore why in this section.

Unemployment type three: Cyclical unemployment.

Cyclical unemployment occurs when there is a temporary downturn in the economy. It explains why the unemployment rate was so high during the 2007–2009 Great Recession and why it came down as the economy recovered. Cyclical unemployment reflects the fact that during a downturn there are lots of unused resources in the economy—unfortunately that includes workers.

Frictional and structural unemployment explain why the equilibrium unemployment rate is above zero, while cyclical unemployment explains why unemployment rises and falls around the equilibrium unemployment rate. In later chapters, we’ll explore why there are temporary ups and downs in the economy and how they lead to unemployment. In this chapter, we’ll examine the unemployment that can persist even when the economy is doing well. So we’ll focus on better understanding what causes frictional and structural unemployment and how these types of unemployment can be reduced.

Frictional Unemployment: It Takes Time to Find a Job

Frictional unemployment includes time spent looking for the right job.

Frictional unemployment occurs when there are enough jobs for everyone, but the process of matching workers to jobs isn’t instantaneous. Searching for a job reflects an information problem—there’s a good job out there for you, but you don’t know where it is. You have particular training, interests, and experiences for a job that would be a great fit for you, but a terrible fit for someone else, and vice versa. The longer it takes for workers and employers to find each other, the higher frictional unemployment will be.

Three major factors determine how much time it takes for workers and jobs to find each other and thus how much frictional unemployment there is. The first is the efficiency of all the technology, networks, and other resources that help workers and employers find each other. The second is the distribution of skills among workers, compared to the distribution of skills needed by employers. And finally, there’s workers’ access to financial support when they’re looking for work. Let’s go through each of these.

The efficiency of the resources employers and workers use to find each other.

Employers and workers have to find each other. They may rely on word of mouth, online job postings, recruiting firms, or career centers on college campuses. Since frictional unemployment reflects an information problem, anything that affects the information that’s available can affect the amount of frictional unemployment. The better workers are at identifying jobs that are a good fit for them, the less time they need to spend searching. Similarly, when managers can use technologies to screen applications effectively, it typically takes less time for them to identify a worker that will be a good fit for them.

The more efficient the resources available for workers and managers to find each other, the lower frictional unemployment is likely to be. Many of these tools are provided by the private sector—job postings, informational interviews, online job boards, headhunter agencies, and job placement services. But there’s also a role for public policy, since improving job matching can lead to less frictional unemployment. That’s why governments often run job-search centers in which they work with businesses to identify unemployed workers with the right skills for their open positions. Similarly, governments try to help job-seekers target their search to the jobs that are the best possible fit for them. Research shows that when workers get access to job-search assistance, they are reemployed faster.

The alignment of the skills workers have and the skills employers desire.

If all workers had the same skills and all jobs used the same skills, then it wouldn’t take very long for workers and jobs to match. Imagine a 500-piece jigsaw puzzle in which all the pieces are identical. It’s a snap to put it together!

But when each piece is unique, you have to find the one piece out of 500 that fits to put it together. Similarly, when workers all differ in their skills and personalities, and jobs differ in their attributes and the skills that they need, it becomes harder for workers and businesses to find each other. So the more diverse workers and jobs are, the more difficult it is for workers and employers to find the right match.

There can also be skills mismatch, meaning that the skills workers have are not the skills that employers want. Technological change and international trade lead to changes in the mix of industries and occupations in which jobs are available, and this can lead to skills mismatch. In fact, the labor market is constantly adapting, with some sectors growing more slowly or disappearing altogether, while other sectors grow rapidly. The United States has become increasingly service-oriented—consulting, other professional services, and health services have grown by millions of jobs since 2000. Meanwhile, goods-producing sectors such as manufacturing have been in decline as technological change has led many workers to be replaced by machines.

When sectors are in decline, it can be hard for workers to find a new job in the industry in which they previously worked. While there are still typically millions of jobs available, they are increasingly more competitive as there are more workers than jobs. Millions of workers change occupations each month, but it can take time for people to realize that their skills are not in as much demand and to seek retraining. As a result, shifts in the skills needed by employers can lead to increases in frictional unemployment as workers take longer to find jobs.

Some people call the changing mix of occupations and industries structural unemployment, but they mean the word differently than we use it. They are referring to structural changes in the labor market that reduce the number of jobs that are a match for the skills and experiences of some workers. But the reality is that throughout your life time you’ll likely need to adapt your skills to the changing needs of the labor market—you’ll probably change occupation (most people do!) and you’ll need to learn to use new technology. Perhaps the most important set of skills you are developing right now is the ability to take in new information and adapt based on what you are learning.

Public policy can respond by helping workers learn what jobs do fit their skills, helping them identify regions where job growth is occurring, and offering job-retraining programs. Retraining programs can reduce frictional unemployment by helping workers develop the skills that are in demand by employers.

Unemployment insurance and other income support during unemployment.

When the government supports people financially during unemployment, unemployment is likely to last longer. Unemployment insurance is a program through which the government provides financial assistance to workers who’ve lost their job through no fault of their own. The program pays a modest amount—no more than half of a worker’s previous wages and typically much less—usually for up to six months. The program’s goal is to reduce the hardships people face as they struggle to pay for housing, food, and other necessities while unemployed.

To understand why unemployment insurance can lead to longer unemployment durations, apply the opportunity cost principle. When you are unemployed you can choose to focus on the jobs that are a best fit for your skills; if you do that, you’ll be more likely to land a higher-paying job that you’ll want to stay in. Alternatively, if you are desperate for cash you might walk into the corner store that has a help wanted sign up and take their minimum wage job. The opportunity cost of staying unemployed to focus on searching for a better job is the wage you could earn by taking that corner store job, or whatever would be the easiest job for you to get.

Unemployment insurance reduces the opportunity cost of another day spent searching because if you took the job, you’d get the wage but lose the unemployment insurance check. So if you could have earned $100 working, but would lose $50 in unemployment insurance, your opportunity cost is only $50. Not surprisingly, when people have unemployment insurance they tend to spend more days searching and focus their search more on the jobs that are the best fit for them.

Studies show that countries offering more financial support to people when they’re unemployed tend to have higher unemployment rates. But studies also show that people without access to unemployment insurance suffer from bigger declines in consumption and more hardship. Moreover, without sufficient savings or unemployment insurance, some people end up settling for worse jobs because continuing to search means not having enough to eat or losing their housing. In these situations, income support during job search can lead workers to better long-term outcomes.

EVERYDAY Economics

Why you should ask your friends to help you find work

Personal referrals help.

Studies show that if you have a personal referral when you apply for a job, you’re more likely to get a job interview—and if you get an interview, you’re more likely to get a job offer, which is also likely to come with a bigger pay package. No wonder people who get job offers through referrals are more likely to accept the offer.

Why is it so great to have a referral? Referrals contain information that’s hard to get elsewhere. It can be hard for employers to credibly learn whether you’re likely to fit in with your co-workers, and whether you’re a hard worker with the right skills for the job. If someone who works at the company vouches for you, she is providing valuable information that the hiring manager can’t easily see in a resume or learn in an interview. And she’s likely to tell the truth—after all, if you get hired, she has to work with you. Similarly, your friend has information about the job you want. She can tell you if workers are happy, if the company is well managed, and whether hard work is likely to lead to a promotion. While you can ask about those things in an interview, it might be hard for a manager to credibly tell you the answers. After all, who’s going to admit to unhappy workers, poor management, and no career path?

Roughly half of available jobs are filled using a personal referral to help make the connection, and about two-thirds of companies have a program to encourage referrals. You may even find that your company offers to pay you a bonus if you refer someone. Sometimes people think that referrals are unfair. But employers use them because referred workers tend to be better matches. Referred truck drivers have fewer accidents than those hired without a referral. Referred high-tech workers generate more patents. And referred workers overall are much less likely to quit. All this means that referred workers are more profitable. Referrals are a win-win situation for job-seekers and employers, but they do mean that people who know more people get a leg up. It’s a good idea to try to get to know—and stay in touch with—people who are in the line of work you want to be in so that you can build your network of potential referrers.

Structural Unemployment: When Wages Are Stuck Above the Equilibrium Wage

Structural unemployment occurs because there simply aren’t enough jobs for everyone who wants to work at the prevailing market wage. In other words, there are structural impediments preventing wages from falling to the point where the quantity of labor supplied is equal to the quantity of labor demanded.

Figure 10 shows that in a well-functioning labor market equilibrium occurs at the intersection of the labor supply and labor demand curves. At that point, there is no structural unemployment—there are just as many jobs as there are workers. However, sometimes wages are prevented from falling to the equilibrium point. Employers demand fewer workers when the prevailing wage is above the supply-equals-demand equilibrium wage. Yet, the quantity of labor supplied is higher because more people want to work at higher wages. Putting these two together reveals that when the prevailing market wage is above the equilibrium wage, there’s a gap between the number of jobs available and the number of available workers. This gap is structural unemployment. The number of people unemployed is equal to the difference between the quantity of labor supplied at the market wage and the quantity of labor demanded.

Figure 10 | Structural Unemployment

The prevailing wage can persist above the equilibrium wage for several reasons. Employers might choose to pay higher wages in order to get employees to work harder, employees might use their bargaining power to demand higher wages, and there might be institutional barriers to lowering wages. Let’s start by considering why employers might choose to pay higher wages, and then we’ll turn to other factors.

Efficiency wages: One cause of structural unemployment.

Happy workers building Fords.

In 1913, Henry Ford made history with the introduction of the moving assembly line in auto production. Workers would stand in place and focus on a single simple task—such as screwing in a particular nut over and over again. This innovation allowed Ford to more than double his production. But he quickly ran into a problem. The work was painfully, mind-numbingly dull. Similar low-skill factory jobs were plentiful in Detroit, so when workers couldn’t take the monotony any longer, they quit. The average worker stayed only a few months, meaning that Ford was constantly hiring and training new workers.

So in 1914, Henry Ford made history again—this time by more than doubling wages to what has famously become known as the $5 day. That doesn’t sound like much today, but back when the prevailing market wage was $2.25, it was a big deal. Applicants flooded his factory gates looking for work. To get a job with Ford in 1914, you had to be two things: a good worker and lucky. If you slacked off on the job, came in drunk, or failed to show up, you were fired. But even if you were a hard worker, there were more workers hoping to land a $5-a-day job than there were positions at Ford. That’s why you also had to be lucky. Persistence also helped, and people would line up day after day, hoping to get hired.

Efficiency wages make it unprofitable for employers to lower wages.

Not only did Henry Ford pioneer the assembly line, but he helped pioneer a new cause of unemployment. Paying higher than the equilibrium wage meant that not everyone who wanted to work at that wage was able to get a job. Those who queued hopefully at the factory gate could have been working elsewhere at the prevailing market wage; instead, they were unemployed, taking their chances at getting a higher-paying Ford job.

Economists refer to Ford’s higher-than-market wage as an efficiency wage—a wage above the prevailing market wage, paid to encourage greater worker productivity. When you’re paid a wage that’s higher than what you can get elsewhere, you’re more careful not to lose it, meaning you don’t slack off, skip work, or antagonize co-workers or managers. Highly paid workers are also more likely to feel valued, inspiring them to give back to their employer in the form of greater effort.

Efficiency wages can lower total labor costs.

Unemployed workers who want to build Fords.

Henry Ford’s problem of rapid turnover ended with the $5 wage. And his workers became even more productive. Any worker who was feeling frustrated simply had to glance out the window at the queue of hopeful workers ready to take his job to be reminded of how good he had it. Workers who quit knew that their next job would probably only pay $2.25. Since the marginal benefit of a new job offer was low compared to what they currently had, Ford’s workers stayed focused on their tasks to avoid being fired. Ford later referred to the $5 wage as one of his greatest cost-saving moves.

Efficiency wages create unemployment.

Ford was able to hire all the workers he wanted at $5 a day because he was paying more than other employers. His higher wage increased labor supply to the Ford plant by encouraging people to try to get a job at his plant. To understand why labor supply increases apply the marginal benefit principle: the marginal benefit of applying rises due to the higher efficiency wage. But not everyone can get hired at the higher wage. Some accept jobs at a lower wage at another auto plant—for them, the marginal benefit of standing outside the Ford factory (the chance at getting the Ford wage premium) isn’t as big as the marginal cost of the forgone wage they would earn working at another plant. But for some workers, that marginal benefit will be big enough that they’ll give up working elsewhere or they’ll enter the labor market in order to stand in line and hope to get their lucky break at the Ford plant.

Institutions: Additional Causes of Structural Unemployment

Efficiency wages are not the only reason why wages don’t fall to bring labor supply and labor demand into balance. The labor market has many unique institutional features that can keep the wage above its supply-equals-demand equilibrium wage. These causes of structural unemployment result in workers with jobs being better off, but their higher wages and compensation and greater job security make jobs scarce for others.

There are three institutional factors that tend to be primary causes of structural unemployment around the world: unions, job protection regulations, and minimum wage laws. Let’s find out more about how each of these can contribute to structural unemployment.

Unions can keep wages high for some workers.

A union strike.

Unions are organizations representing workers who band together to negotiate jointly with their employers. Unionized workers earn about 15% more than a comparable worker in a non-union job and often receive better benefits.

There are lots of reasons why unions are effective. Unions give more bargaining power to workers, allowing them to extract some of the profits that might otherwise go to management or investors. They might have different information than management, allowing businesses to make better decisions because they have an effective way to gather input from workers. Regardless of the reason, union wages mean that more workers want union jobs than there are union jobs available, and employers might demand fewer workers at the higher wage. The result is structural unemployment.

Unions aren’t a big deal in most industries in the United States. Only around 7% of private-sector workers are unionized. However, unions play a much larger role in education and other public-sector jobs. In other countries like Belgium, Norway, and Germany, unions play a large role in the labor market.

Job protection regulations make it hard to fire workers.

If you want to reduce the number of people unemployed, why not just make it harder for businesses to fire people? This is a strategy that many countries have tried. But let’s think through what you’d do as a manager. When you consider whether to hire someone, you know that if it doesn’t work out, you’ll either have to keep paying that person anyway or pay a large price to let them go. Not surprisingly, that ends up causing you to think twice before making someone a job offer. You’ll want to be confident that they’ll generate enough additional revenue to justify their wage; after all, if they don’t, you can’t fire them.

Let’s also think back to the reasons employers pay efficiency wages—workers are more productive when they don’t want to lose their jobs. So what do you think happens to worker productivity if employers can’t fire workers? Some workers may decide to slack off, knowing that it’s hard for them to be fired. Because workers are less productive, employers want to hire fewer of them.

Taken together, while job protection policies succeed in reducing the number of people who lose their job, they also reduce the number of workers businesses want to hire at any given wage. These policies reduce labor demand and thus employment is lower than what would occur without these policies. These policies could result in lower wages or they can exacerbate structural unemployment if there are other factors making it hard for wages to fall. Such policies can also increase frictional unemployment by encouraging employers to search longer to find a good match. This leads to a dynamic where fewer workers are willing to leave jobs because they know it will be hard to find another job. Job protection regulations make for a less dynamic and less flexible labor market.

The challenges of high firing costs are apparent in Europe, where some countries make it hard to fire workers. In France and Italy, employers need to have a government-approved reason to fire a worker, and there are obstacles to laying off many workers at once. Such policies are good for people who are already employed and want to stay in their current jobs. But they’re not good for the unemployed workers who want to change jobs or employers.

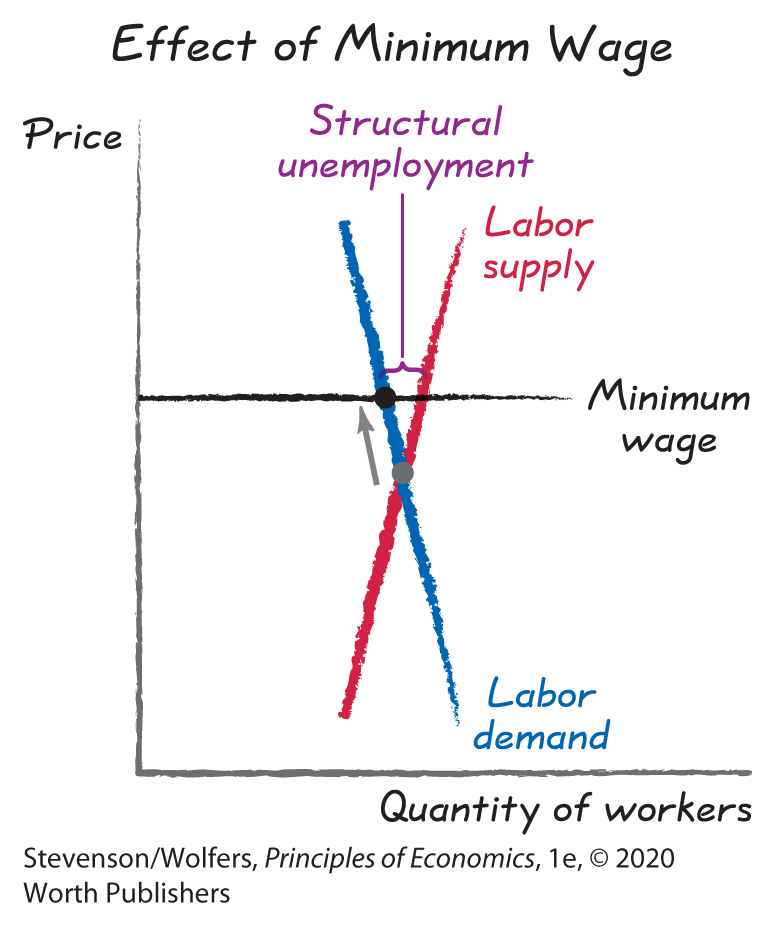

The minimum wage keeps wages from falling below the set minimum wage.

The federal minimum wage law says that your employer can’t pay you less than $7.25 per hour. Some states have their own higher minimum wages. If the minimum wage is higher than the equilibrium wage, businesses want to hire fewer workers. Yet more workers want to work at the higher wage. The resulting gap between the labor supplied and labor demanded is structural unemployment.

The minimum wage is a hotly contested issue. Opponents focus on the unemployment that’s created by the minimum wage. Setting the minimum wage too high will lead to fewer jobs. For many, unemployment is even worse than a low-wage job. Proponents argue that the poor earn low wages because they lack bargaining power relative to employers, and a slightly higher wage won’t lead to much of a change in the labor market. Essentially, they argue that neither supply nor demand for labor changes very much with the wage.

Economists who’ve studied the effects of raising the minimum wage suggest that raising the minimum wage leads to a negligible change in overall unemployment. Most workers earn wages well above the minimum wage, and thus the minimum wage applies only to a small subgroup of workers. Among minimum wage workers, many studies find only small changes in the number of workers hired, although economists disagree about just how big or small the effect is. The change in unemployment also depends on just how high the minimum wage is relative to the supply-equals-demand wage: the higher it is the more structural unemployment there’ll be.

The biggest impact of minimum wage laws is on the unemployment rate of teenagers—more of whom want to work when the minimum wage is high, but fewer of whom are desired by employers. Instead, slightly more experienced or older workers get the jobs.

Recap: Frictional and Structural Unemployment

Frictional and structural unemployment explain why the equilibrium unemployment rate is above zero. Frictional unemployment occurs because looking for a good job takes time. Structural unemployment occurs when more people want to work at the prevailing wage than there are employers desiring workers. You’ve also seen that there are things government can do to reduce frictional and structural unemployment, but there are other things government does that can increase these types of unemployment. Sometimes these choices involve trade-offs—like helping people get through unemployment with less hardship versus encouraging them to take a job right away. To better understand these trade-offs, we’ll next turn to the costs of unemployment for individuals and society.