24.2 Different Measures of Inflation

Inflation data are used for many different tasks: They’re a guideline for cost-of-living adjustments, an input to adjusting financial and economic indicators, a guidepost for Federal Reserve policy makers, and an indicator that forecasters use to project where the economy is going. Each role is best served by slightly different measures of inflation. While the CPI remains the most popular measure of inflation, it is in fact just one of several price indices that can be employed to meet the needs of specific decision makers. Different measures of inflation consider different baskets of goods and services, and are therefore useful for different tasks.

Consumer Prices

So far we’ve been focusing on the prices that consumers pay when they buy goods and services. Let’s take a look at how various measures of inflation in consumer prices differ, and what each is useful for.

The CPI is used for cost of living adjustments.

The CPI is the most widely accepted measure of the change in cost of living. That’s why workers who want to protect themselves from the effects of the rising cost of living insist that their employment contracts include indexation clauses which automatically adjust their wages in line with the CPI. The government also indexes Social Security and other payments so that they’re automatically adjusted to keep pace with the rising cost of living. And the income cutoffs to qualify for many government programs are automatically adjusted each year to account for inflation.

Monetary policy focuses on the personal consumption expenditure deflator.

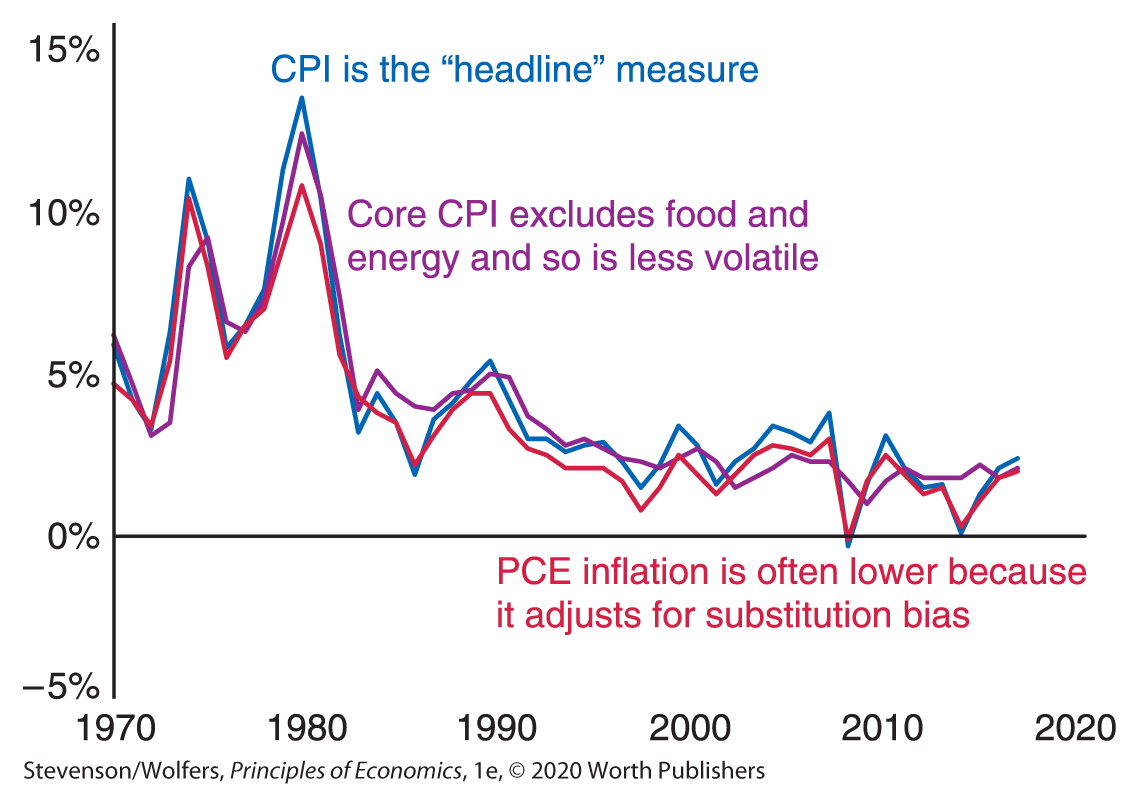

Figure 5 | Alternative Measures of Inflation Move Together

Data from: Bureau of Labor Statistics and Bureau of Economic Analysis.

One of the key goals of the Federal Reserve is to achieve low and stable inflation. Indeed, as we’ll discuss in Chapter 34, it tries to manage the economy to hit a target rate of inflation of 2%. But rather than focus on the CPI, the Fed sets this target in terms of the personal consumption expenditure deflator (or the PCE deflator, to its friends). This alternative measure of inflation is based on a slightly different basket of goods and services, which also includes items that you consume but don’t pay for directly, like medical care paid for you by your employer or the government. The goods and services in the PCE basket are continually updated, so (much like the chained CPI), it accounts for changing patterns of spending. This means that the PCE does not have the problem of substitution bias that the CPI has. As Figure 5 shows, the Fed’s preferred measure of PCE inflation moves in lockstep with CPI inflation, though it is often lower due to the correction for substitution bias.

Forecasters focus on core inflation.

When forecasters look for the underlying trend in inflation, they consult an alternative measure of inflation that excludes food and energy. This measure is called core inflation. Sometimes people think this is odd because food and energy are two of the most critical purchases people make. They are excluded not because they aren’t important, but because their prices are often volatile and they don’t track broader inflation trends. Food prices rise and fall with agricultural harvests, and oil prices fluctuate with geopolitical tensions. Excluding these volatile prices often provides a clearer reading of underlying inflation trends. As Figure 5 illustrates, core inflation tends to be similar to the headline measure, but it bounces around a bit less.

Business Prices

The CPI is designed to measure inflation as experienced by people in their day-to-day lives. But what if you’re running a business? Then you might care about the prices of inputs into your production process or the price at which you can sell your output. Similarly, if you want to know if a country is producing more output or just charging higher prices, you need to account for inflation in the prices of all the goods and services that are produced.

Inflation experienced by businesses is measured by the producer price index.

The producer price index (or PPI for short) measures the price of inputs into the production process. It’s useful because it helps businesses see how the prices that matter to them are changing. It’s also useful because it can help you keep tabs on what’s likely happening to your competitors’ costs. From a macroeconomic perspective, it’s worth tracking the inflation that businesses are facing because rising input prices eventually cause businesses to raise their prices.

The GDP deflator tells us about the rising prices of all goods and services produced.

When you’re adjusting dollar amounts describing what the economy produces, you should focus on the GDP deflator, which is an alternative price index that’s calculated based on a basket of goods and services that represents everything the U.S. economy produces. That means it accounts for the prices of everything we make from sandwiches to submarines, and unlike the CPI, it includes capital goods but excludes imported goods. The GDP deflator is particularly important because it can be used to convert nominal GDP into real GDP. Recall from Chapter 21 that real GDP is measured using a fixed price level so that it isolates changes in the amount of stuff being produced from changes in the price level. That means we can compare real and nominal GDP to compute the GDP deflator:

Now that you know many different measures of inflation, let’s turn to adjusting for the effects of inflation.