24.4 The Role of Money and the Costs of Inflation

People really dislike inflation. In one survey—taken when inflation was below 2%—more than half of Americans described rising prices as a “very big problem,” while another third called it a “moderately big problem.” Surveys of economists reveal that they think inflation is costly, but they’re a bit less concerned. We’re going to explore both why the general public is so concerned by inflation, and what economists believe are the true costs of inflation. But first, we need to turn to the topic of money.

The Functions of Money

You’ve probably spent much of your life thinking about money, worrying about money, or dreaming about money. But have you ever just sat down and thought hard about what money is? It’s not just the pieces of paper in your wallet; it’s also the deposit in your checking account and the bits and bytes in your Venmo account. Money is any asset that’s regularly used in transactions.

More importantly, think about what money does. It’s an essential component of our modern economy because it serves three key functions: It’s a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. Let’s explore each of these in turn.

Function one: Money is a medium of exchange.

You’re using money as a medium of exchange whenever you hand it over to buy stuff, or alternatively, when you accept it from your employer in exchange for your hard work. If there were no such thing as money, you would either have to make everything you need for yourself, or barter for it. But barter constrains you to only do business when there’s a double coincidence of wants: You can only trade your extra milk for bread if you can find someone who wants milk and coincidentally has extra bread.

Money eliminates this constraint, creating opportunities for you to specialize. You can focus on the narrow set of tasks where your skills are most valuable, knowing that you can spend the money you earn to buy fresh bread from a professional baker, a smartphone manufactured in Chinese factories, and shares in Amazon. Without a widely used medium of exchange, bartering small slices of your workday for some bread, a smartphone made on the other side of the world, and part ownership of an online company would be a logistical nightmare. With money, it’s an everyday convenience.

But money can only be an effective medium of exchange if it’s widely accepted. And that depends on sellers maintaining faith that when they accept money, they’ll subsequently be able to use it to buy stuff at reasonable prices.

Function two: Money is a unit of account.

A common unit of account makes these comparisons easier.

Money is also a unit of account, which means that it’s a common unit that people use to measure economic value. Indeed, just as nearly all architects use yards to measure distance, nearly everyone uses dollars as the common unit to describe prices, record debts, and write financial contracts. Putting everything in the same unit is useful because it makes it easier to apply the opportunity cost principle and ask, “Or what?” If apples cost $1 a pound and oranges cost $1.25 a pound, then you know you have to give up more apples to get a pound of oranges.

It’s important to have a stable unit of account for measuring economic value for the same reason that it’s useful to have a stable unit of account to measure distance—it simplifies comparisons and eases communication. If your architect’s measuring tape were to shrink or expand each day, it would no longer be very useful. The same is true for money—the value of a dollar needs to be relatively stable for it to be a reliable unit of account.

Function three: Money is a store of value.

You could store your wealth this way, but do you really want to?

When you save money for a rainy day, you’re using money as a store of value, storing your purchasing power for another day. Want to ensure that you have goods and services to consume in retirement? You can do that by earning money today, saving or storing that money, and then using it in the future to buy stuff. While there are other ways of shifting wealth to the future—you could try storing gold bricks, fine art, or canned food instead—none of these is a good store of value: the price of gold fluctuates a lot, fine art is hard to store, and canned food loses its value as it reaches its expiration date.

Money will successfully function as a store of value when it’s easy to store and it can reliably hold its value over time.

Inflation undermines the productive benefit of money.

Money plays a productive role in the economy similar to a lubricant that keeps the economic engine operating efficiently. When inflation is low and stable, money serves its three functions well, and the economic engine hums along.

But when inflation is high or unpredictable, problems emerge. You’ll be less willing to use money as a store of value if rising prices mean that the $100 you put in your wallet today will only buy half as much next week. Money is also a less effective unit of account when its value is uncertain, because a price denominated in dollars is less informative when you aren’t sure what a dollar is worth. You’ll be less willing to sign an employment contract spelling out your future wages in dollar terms if you can’t be sure those dollars will buy you a reasonable quality of life. Skyrocketing inflation can undermine the role of money as a medium of exchange when it becomes too much of a hassle to get your hands on enough cash, push it around in wheelbarrows, and spend it before it loses its value. Likewise, sellers will stop accepting money if they fear that they won’t be able to spend it.

As we’re about to see, when inflation makes money a less effective economic lubricant, it can cause the whole economic engine to seize up.

The Costs of Hyperinflation

The costs imposed by inflation become most obvious in the worst-case scenario of an extremely high rate of inflation, also called a hyperinflation. There’s no precise cutoff between a high inflation rate and hyperinflation, but think of prices at least doubling every few months. Fortunately, hyperinflation is rare. One of the most famous examples is the chaotic German hyperinflation of 1922–23, when prices doubled every few days!

Unfortunately hyperinflation continues to be a modern reality. Recently Venezuela has struggled with hyperinflation. An annual inflation rate measured in thousands of percent per year has pushed the price of a café con leche—a delicious local coffee drink—from 450 Venezuelan bolivars in mid-2016 to 800,000 bolivars less than two years later, as you can see in Figure 8.

Figure 8 | Price of Café con Leche in Venezuela

Data from: Bloomberg.

Hyperinflation makes most aspects of life harder.

Within a few years, a crate of bolivars that would have bought a house could no longer buy a carton of eggs. The currency became so worthless that when thieves looted a store, they left behind dozens of 20 bolivar bills because they didn’t think it was worth the effort to pick them up.

Venezuela’s experience illustrates how the logistical challenges of dealing with hyperinflation come to dominate everyday life. In late 2016, the highest denomination note, 100 bolivars, had become worth less than a nickel. The government responded by printing even higher value notes. But inflation raced ahead even faster, and soon the new 100,000 bolivar notes also came to be worth less than a nickel. As a result, it takes heaping fistfuls of cash to buy anything. Wallets can’t fit enough cash, so people have taken to stuffing bundles of notes into backpacks. One shopkeeper said that instead of counting banknotes he weighs them using the same scales he uses to weigh cheese. Bank branches regularly run out of money. All of this wreaks havoc with ATMs, some of which needed to be refilled every three hours. For some people, the only way to get cash is to wait in a long ATM line in which the withdrawal limit is so low they can only get enough bolivars to pay for a few bus rides. Some stores have responded to the shortage by selling cash to customers, who buy it with a credit card. But the markups are steep, and you might pay a 180,000 bolivar credit card charge to get a 100,000 bolivar note.

Hyperinflation erodes all the functions of money.

A huge stack of Venezuelan bolivars that’s now worth less than US$2.

Hyperinflation destroyed the bolivar as a store of value. Indeed, the bolivar lost its value so quickly that Venezuelans would race to spend their cash before it became worthless. The hassle required to get cash also made the bolivar an unattractive medium of exchange. Instead, people figured out workarounds. Barter became more common—taxi drivers took cigarettes in lieu of cash, a haircut could be bought for five bananas and two eggs, and Facebook pages sprang up so that people could swap toothpaste, baby formula, and other essentials. Folks who were well-connected used U.S. dollars instead of Venezuelan bolivars. American Airlines refused to accept bolivars for flights out of Venezuela, insisting their customers use foreign credit cards to buy their tickets online. Amid all this chaos, there was no reliable unit of account in Venezuela. Even in real estate, where the law requires contracts to be written in bolivars, a group of realtors established a password-protected website that lists the prices of houses in U.S. dollars.

The Venezuelan hyperinflation aptly illustrates the problem that arises in every episode of hyperinflation—when money no longer works as it should, every facet of economic life becomes more difficult. As one Venezuelan said, “Something so simple as taking money out of a bank machine or buying a coffee or taking a taxi has become a race for survival.” While hyperinflation is not the only problem in Venezuela—add in a big dose of corruption and mismanagement and stir—the result was an economic depression, widespread poverty, and a humanitarian disaster in which millions of people starved despite living in a country blessed with extraordinarily valuable oil reserves.

The Costs of Expected Inflation

While hyperinflation illustrates the costs of high rates of inflation, it’s worth remembering that this is an extreme outcome. More moderate rates of inflation have more moderate costs. At the other extreme, some economists argue that the 2% inflation rate that the United States aims for is close enough to price stability that it imposes few costs. But when inflation creeps a bit higher—as it did in the 1970s when it averaged 7% and rose as high as 14%—it becomes more disruptive. We’ll explore this by first analyzing why expected inflation is costly, and then turn to the extra costs that arise when inflation is unexpected.

Cost one: Inflation creates menu costs for sellers.

Put yourself in the shoes of a manager who has to decide how many times to change their prices each year. The marginal principle reminds you that it’s simpler to ask whether to raise your price one more time. The cost-benefit principle says: Yes, adjust your price today if the marginal benefit of doing so exceeds the marginal cost. The cost to a restaurant of raising prices is printing new menus, which is why economists describe the marginal cost of adjusting your price as menu costs. The marginal benefit of adjusting your price is that you’ll shift to a price that covers the rising cost of your inputs. The higher inflation is—and the faster your costs rise—the larger this marginal benefit is. As a result, higher inflation leads to more frequent price adjustment.

Inflation is costly because it leads businesses to devote valuable resources to reprinting menus, adjusting price tags, and reprogramming vending machines more often. These costs arise because inflation renders money an unstable unit of account—prices are marked in dollars, but those dollars are worth less—and so last year’s price is no longer suitable this year.

Cost two: Inflation creates shoe-leather costs for buyers.

People waiting to get cash in Venezuela.

Next, think about how inflation will affect your relationship with money. Every time you go to the ATM you have to decide how many dollars to withdraw and how much to leave in your account earning interest. This is a “how many” question, so the marginal principle says to focus on the simpler question of whether to withdraw one extra dollar. The cost-benefit principle says yes, withdraw that extra dollar if the marginal benefit exceeds the marginal cost. The marginal benefit of withdrawing an extra dollar is the convenience of having more cash in your wallet that you can use to buy stuff. The marginal cost comes from the opportunity cost principle, which reminds you that every dollar you withdraw would otherwise stay in your savings account earning a real interest rate. Inflation adds another cost: As prices rise, the cash in your wallet comes to be worth less. This cost is a big deal in Venezuela, because the 100,000 bolivar note you have in your wallet this week might only buy half as much next week. It follows that when inflation is high, the marginal cost of holding money is high, leading people to hold less of it.

Just as inflation erodes the value of banknotes, it also eats into the value of the balance in your Venmo or checking accounts. So inflation will also lead you to hold less of these other forms of money. As many Venezuelans have discovered, that means you’ll need to visit your bank more often, withdrawing money only as you need it, and rushing to spend it quickly. The time and effort this takes are called shoe-leather costs, because they arise from running around town (which wears down the leather on your shoes). Shoe-leather costs arise because inflation undermines money’s function as a store of value, forcing people to take costly measures to keep their wealth in assets that better maintain their value.

The Costs of Unexpected Inflation

So far we’ve considered the costs that arise when everyone expects inflation to occur. There are additional costs that occur when inflation is unexpectedly higher or lower than anticipated.

Cost three: Inflation confuses the signals that prices send.

Did the price rise because demand for quinoa increased, or is it just inflation?

Microeconomics teaches us that prices play a key role in coordinating economic activity. An increase in the price of an individual good like quinoa is a signal from buyers that they really want quinoa; the price transmits this information to quinoa producers, who see it as an incentive to expand production. By contrast, macroeconomics teaches us that when inflation causes all prices to rise, there’s no reason to expand production because the higher price of your output is matched by an equal rise in the price of your inputs.

The problem is that if the price of quinoa rises, it can be hard for producers to figure out whether that higher price is due to increased demand for quinoa or to a burst of unexpected inflation. In the resulting confusion some managers will respond to unexpected inflation by expanding production, although they’ll later discover that was a mistake because their costs have risen. At other times they’ll fail to expand production when demand for their product has risen because they mistakenly guessed that the higher price reflected an unexpected burst of inflation. These mistakes occur because inflation undermines the stability of dollars as a unit of account, and this instability confounds the signals that price sends.

EVERYDAY Economics

The costs of grade inflation

Figure 9 | Average Grades Have Risen at Nearly Every College

Data from: www.gradeinflation.com.

Back in 1950, the average grade at Harvard was roughly a

This grade inflation is costly, for the same reasons unexpected inflation is costly—it distorts the signals that grades send. Grades are most useful when they signal your ability to potential employers. But grade inflation makes it hard for employers to know whether you have a high GPA because you’re an exceptional student or because you graduated from a school that pumped up everyone’s grades.

Cost four: Inflation redistributes.

Unexpected inflation also redistributes from savers and lenders toward borrowers. This occurs because most loans specify repayment schedules in nominal terms—they use dollars as the unit of account—and so unexpected inflation changes the real value of your repayments. For instance, if you borrow $15,000 to buy a car at a 5% nominal interest rate, the repayment schedule commits you to pay $283 per month for the next five years. Perhaps that 5% nominal interest rate reflects expectations of 2% inflation and a 3% real interest rate. But if inflation ends up being higher—say if it’s 4%—then the real interest rate you’ll pay will be 1%, instead. You’ll gain, and your bank will lose, because even though you’ll keep sending in that $283 each month, the dollars you send your bank aren’t worth as much.

Inflation that’s higher than expected is good for borrowers and bad for lenders.

When this happens, lenders can go broke, as many did during the 1980s “savings and loans crisis.” The seeds of the crisis were sown in the 1960s, when expectations of 2% inflation led some lenders to make long-term loans at nominal interest rates as low as 5%. Then inflation unexpectedly rocketed above 10% in the 1970s and it stayed high through to the early 1980s. This unexpected inflation was good news for borrowers, because their monthly loan repayments remained fixed in dollar terms even as their nominal income rose. But for lenders, it was disastrous. They had loaned money at what turned out to be a negative real interest rate, so in inflation-adjusted terms, borrowers repaid less than they borrowed. Many financial institutions went belly-up as a result.

On the flip side, when inflation is lower than anticipated, the opposite happens: The real value of your repayments rises, so lenders gain at the expense of borrowers. This happened in the United States in the early 1980s, when the Federal Reserve brought inflation down faster than anyone expected. Borrowers who had expected inflation to continue at 10% had signed up for 30-year mortgages charging nominal interest rates of 15%. When inflation nosedived—it fell as low as 2%—they ended up paying extremely high real interest rates. Banks made huge profits at the expense of homeowners, many of whom struggled to meet these higher-than-anticipated real mortgage payments.

The Inflation Fallacy

Ok, now you know the costs of inflation. Inflation has very real costs, and economists worry about inflation. But you might have noticed that it’s not for the reasons that most people worry about inflation. People worry about inflation because they go to the store and see higher prices. That sounds bad. If you have to pay more for what you’re buying, then you can’t buy as much as before, right? Surveys show that more than three-quarters of people agree that inflation erodes their purchasing power. But that’s only true if your income stays the same, which it rarely does. Inflation means that on average all prices are rising, and that usually means that wages and salaries are also rising.

The inflation fallacy is the (mistaken) belief that inflation destroys purchasing power. It’s a fallacy because it tells only half the story. While a $1 price rise makes a buyer $1 poorer, it also makes the seller $1 richer. It follows that higher prices don’t destroy purchasing power.

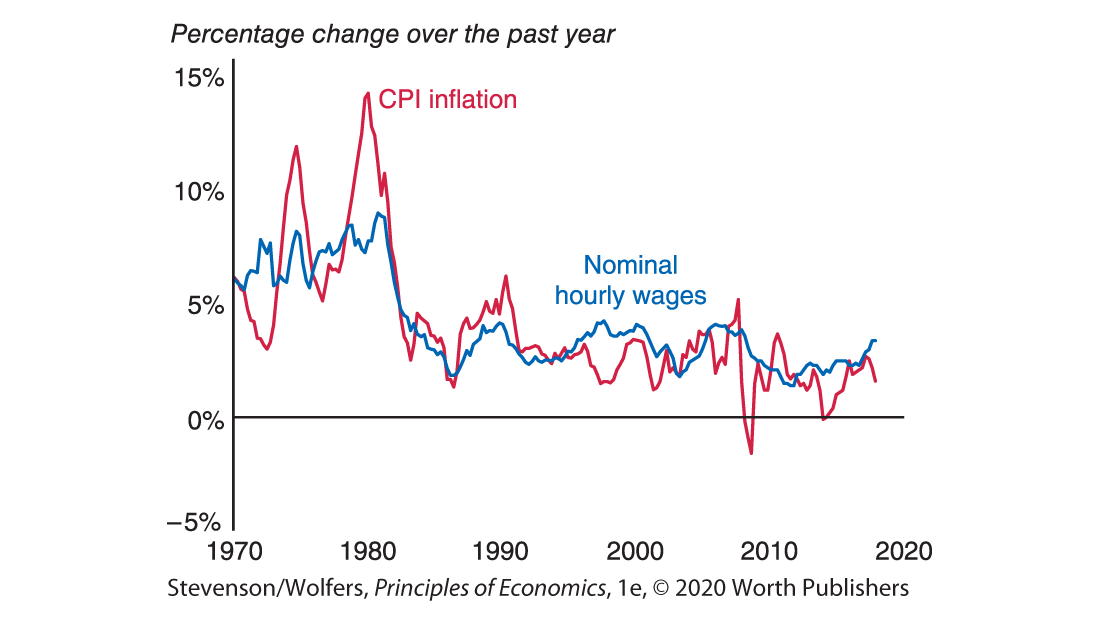

Moreover, inflation is a generalized rise in all prices, and so it raises the price of what you sell just as much as it raises the price of what you buy. You sell your labor, and inflation typically boosts the price of labor—meaning your wages—in lockstep with the price of the stuff you buy, as shown in Figure 10. Likewise, the price of the stocks in your portfolio and the interest you earn on your savings rise with inflation, leaving your purchasing power roughly unchanged.

Figure 10 | Nominal Wages Grow in Lockstep with Inflation

Data from: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The inflation fallacy reflects a psychological bias in which people are quick to blame inflation for the higher prices they pay, but take personal credit for the parallel rise in their nominal wages, interpreting it as a well-deserved reward for their hard work unrelated to inflation. While their logic is wrong, their unhappiness is real, making inflation a potent political issue.

It’s the real stuff that matters, not how it’s measured.

To see the error that drives the inflation fallacy, consider the following thought experiment. Imagine that you wake up on New Year’s Day, and every price tag in the economy has an extra zero on the end of it. Gumballs sell for $2.50 instead of a quarter. Trinkets at the dollar store sell for $10. And a pair of jeans sells for $500 instead of $50. It’s not just the price of stuff that changes, but the price of everything. Your wage will rise from $12 per hour to $120. That $10 bill in your wallet now says “$100.” And your bank statement says that your $400 in savings is now $4,000. Everything involving a dollar sign gets multiplied by ten. It’s like the dollar has shrunk and its value is one‐tenth what it was before. But in another sense, nothing has changed, because everyone has ten times as many of these shrunken dollars.

What if it shrank?

Now think about how this new economy will work. Apart from all those extra zeros floating around, nothing will change. Your purchasing power won’t change, because your paycheck is ten times higher to compensate for prices being ten times higher. You won’t change how many gumballs, trinkets, or jeans you buy, because the opportunity cost of buying each of these items remains unchanged. More generally, you won’t change what stuff you buy, what you’ll produce, or how many hours you work. Indeed, no one will change the quantities of the stuff they buy, sell, produce, or do. So that means that across the whole economy, this purely nominal change—a change in the number of zeros on each price tag—will have no effect on real variables: There’ll be no change in the total amount of each good purchased, the quantity of production, or the purchasing power of your income.

This thought experiment highlights the idea that the costs of inflation aren’t due to the price level being higher. Rather, it’s the process of changing all these prices that’s costly. The process of changing prices leads sellers to incur menu costs, buyers to incur shoe-leather costs, and unexpected price changes also create costly confusion and arbitrary redistribution.