25.3 The Macroeconomics of Consumption

We’ve now uncovered the two big ideas that are the building blocks of the macroeconomics of consumption. People make decisions about how much to consume—and thus how much to save—considering their permanent income, and they prefer to smooth consumption over time. Because these forces drive individual people’s consumption choices, they also drive total consumption in the economy. And so these two big ideas have important implications for the macroeconomic link between total income and total consumption. They’ll help you see where the economy is going and better understand how total consumption will change in response to changing macroeconomic conditions.

The Relationship Between Consumption and Income

Income is an important determinant of consumption and when income changes, consumption changes. But there are different kinds of changes in income and these different kinds of changes in income have different implications for consumption. We’ll now dig into five important insights that will help you identify different types of income changes and how those changes will likely impact consumption.

Insight one: A temporary change in income leads to a small change in consumption.

Don’t spend it all at once.

What would you do if you won a $1 million lottery? A lottery win is a temporary boost in income because you don’t expect to win it again. So how would you adjust your consumption in response? I hope you won’t go out and blow the whole million bucks tomorrow. I hope that you don’t even spend half of it right away. A financial planner might advise you to spend $50,000 of it each year, so that you can enjoy higher consumption for the rest of your life.

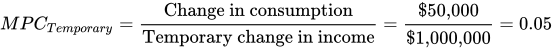

The desire to spread a temporary spike in income out over your lifetime is why a temporary increase yields only a relatively small increase in consumption. In this example, a temporary increase in income leads this year’s consumption to rise by only $50,000. This yields a marginal propensity to consume (or MPC) out of a transitory rise in income of 0.05:

Insight two: A permanent change in income leads to a large increase in consumption.

A new job that’ll boost your income by $50,000 per year forever is a much bigger deal than a one-off signing bonus of $50,000 that only temporarily raises your income. It’s a bigger deal because a permanent change in income leads to a much larger change in your lifetime income. As a result, a permanent change in income leads to a larger change in consumption. This means that the marginal propensity to consume out of permanent income is much higher than it is out of temporary income.

Getting named as one of Forbes 30 under 30 means that your permanent income might be higher than you thought.

For example, perhaps when you graduate you’ll land a job as a first-year analyst at Goldman Sachs with a starting pay of $110,000—which is much more than you ever expected. Even better, that initial job puts you on a career path in which you can expect to go on to earn even higher wages throughout your career. So it’s not just a one-year boost, your future income is now a lot higher than you had previously anticipated. How should you respond? If your job at Goldman Sachs means that your income will be $50,000 per year higher than you anticipated, and you’ll get that unexpected boost every year for the rest of your life, then that means that your permanent income has risen by $50,000 per year. Unlike a one-time gain, which you allocate over your remaining years of life, a permanent increase in your annual income means that you can enjoy increased consumption and income every year for the rest of your life.

The marginal propensity to consume out of a rise in permanent income is typically fairly high. In fact it could be as high as 1:

To summarize: an unanticipated change in income that’s likely to continue every year for the rest of your life yields an equally large change in permanent income, and so there is a correspondingly large increase in consumption.

Interpreting the DATA

What is your permanent income?

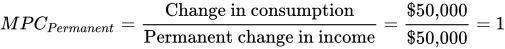

We’ve seen that your level of consumption should reflect your permanent income. But what is your permanent income? I don’t know you personally, but a useful starting point is to analyze the typical earnings of other college graduates who work full time. By looking at graduates at different points in their career, you can see how your earnings are likely to evolve throughout your career.

Figure 7 illustrates the typical earnings of folks at different points in their careers. We focus on the median because half the people earn more and half earn less. Those with only a high school diploma typically earn around $34,000 per year over the course of their careers; they start lower and their income grows very little over their lifetime as they gain experience. For those with associate’s degrees, the career average is $46,000; and for those with a bachelor’s degree, it’s $71,000. With more education, you not only start your career with higher earnings, but your earnings will tend to grow more sharply as you gain experience. This is even more true for economics majors, who typically earn an average of $94,000 per year over the course of their careers. In other words, choosing to go to college and major in economics is even better than winning a million dollar lottery—because relative to not attending college—your income and thus consumption will be about $60,000 higher per year throughout your career.

Figure 7 | Median Annual Earnings of Full-Time Workers over the Course of a Career

Data from: Hamilton Project.

But don’t expect to be making money like this straight away. As Figure 7 shows, starting salaries are about half what they are at midcareer. So your earnings right out of the gate don’t represent your permanent income, and it’s likely your income will keep growing for another decade or more.

Insight three: An anticipated change in income leads to no change in consumption.

Your permanent income is your best estimate of your long-term average income, and so it reflects your expectations about how your income will evolve over time. As such, it already factors in anticipated future changes in your income. And so if you set your consumption in line with your permanent income, then anticipated changes in income won’t affect your consumption. As a result, the marginal propensity to consume out of anticipated changes in income is zero.

To see this concretely, put yourself in the shoes of a polling expert expecting to earn $60,000 in even-numbered years (when there are a lot of elections), but $40,000 in other years (when you have fewer clients). Instead of cutting your consumption spending every second year only to raise it the next, you’ll be better off spending $50,000 each year, which is in line with your permanent income. And so the anticipated rise in income in an election year has no effect on your consumption, just as the anticipated cut in income in odd-numbered years has no effect.

Insight four: Learning about a future income change leads to a change in consumption.

When does consumption respond to changes in future income? If you’re basing your consumption on your permanent income, then you’ll respond as soon as you get the news about a change in your future permanent income, rather than when the money actually arrives. (By that time, it has been fully anticipated and already factored in to your spending decisions.)

For instance, if your employer unexpectedly announces that in a year’s time everyone will get a 4% higher-than-normal raise, then a consumption smoother will use that information to boost their consumption right away. This also works the other way—if your company unexpectedly announces a pay freeze such that next year’s expected pay raise disappears, the permanent income hypothesis suggests that you should cut your consumption right away.

The broader point is that today’s consumption can be quite sensitive to expectations about future income. This also suggests that changes in macroeconomic policy might have their largest effect on consumption when they’re announced, rather than when they actually go into effect.

Insight five: It’s hard to forecast changes in consumption.

The final implication of all this is that changes in consumption are very difficult to forecast. After all, we’ve seen that consumption does not change much in response to anticipated changes in income. It only responds to unanticipated changes in income. But unanticipated changes are, by their nature, very difficult to forecast. After all, if they were easy to forecast, you would have anticipated them!

If changes in individual consumption are difficult to forecast, then it follows that changes in total consumption—the sum of the consumption decisions of millions of individual Americans who follow a similar logic—should also be difficult to forecast.

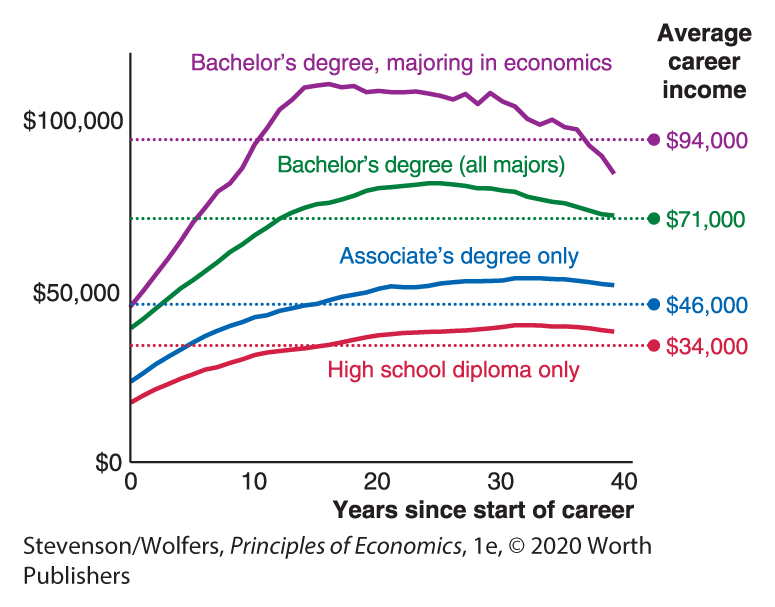

Figure 8 | Changes in Consumption Are Difficult to Forecast

Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

It’s worth being careful about this implication. It doesn’t say that the level of consumption is difficult to forecast. In fact, it’s not: The level of consumption is usually about two-thirds of GDP. Instead, it says that future changes in consumption are hard to predict. Take a look at the annual changes in aggregate consumption shown in Figure 8, and I think you’ll agree that changes in consumption are hard to forecast. The change in consumption in each year appears roughly unrelated to what happened in previous years. And because consumption is a big chunk of GDP, this also means that it’s awfully difficult to predict changes in GDP.

Adding Behavioral Economics and Credit Constraints to Our Analysis

We’re exploring these ideas to give you a window into the thinking that underlies the consumption choices of the millions of Americans who make up the macroeconomy. Along the way you might have wondered: Do people actually make their consumption choices like this? As you might have guessed, there are limitations to how much people can smooth their consumption. It relies on people knowing a lot about their future income and being able to both borrow and save when required. Unfortunately, borrowing and saving isn’t always easy or even possible.

These practical limitations don’t undermine our previous insights, but they do require us to modify them slightly. Let’s start by looking at the problems people can run into, and then we’ll see what this means for the insights we’ve developed about the relationship between income and consumption.

People can’t always borrow.

Some people don’t follow the Rational Rule for Consumers simply because they are unable to borrow. Credit constraints limit the amount that some people can borrow. If you don’t have savings or credit, you’re constrained to only spending no more than what’s in your latest paycheck, and therefore you can’t smooth your consumption. This is an important constraint for many Americans.

Credit constraints arise because banks are often reluctant to lend money to fund consumption when the loan isn’t backed by collateral—an asset they can take over if you fall behind on your repayments. This means that you’ll find it easier to borrow for certain kinds of spending, like buying a house or a new car, because the bank retains the right to foreclose on your house or repossess your car. But it’s much more difficult to find a bank willing to lend you money to buy groceries or pay the rent if you don’t have sufficient current income. And yet you’re most likely to want to borrow money to fund consumption when your income is temporarily low, such as when you’re unemployed. Banks are also reluctant to loan money to people who have yet to build up a solid credit history, and this makes it difficult for students to borrow all that they need to consumption smooth.

It’s hard to make deliberate forward-looking plans and stick to them.

Planning is hard work, but worth it.

Even if banks were willing to lend to you, it’s really hard to perfectly forecast your permanent income and make consumption plans that you stick to. Our insights into consumption come from applying a framework that’s deliberate, forward-looking, and requires thinking hard about difficult trade-offs. Following the Rational Rule for Consumers requires you to constantly compare the present to the future, to make plans about when to spend and when to save, and to follow through on those plans.

The reality is that not all consumers are this deliberate about their choices all the time. I bet you’ve occasionally made spending decisions without a careful evaluation of marginal benefits. Too many students refuse to draw up a budget when their financial aid check arrives. And even among those who do, temptation or unexpected needs can get in the way, disrupting even the best-laid plans. The bottom line is that cognitive or behavioral limitations—from being poorly informed, tired, or impulse-driven—mean that some people don’t smooth their consumption. They don’t save enough; they run up debt without a plan to pay it back; and they make impulse purchases.

Incorporating insights from psychology into our understanding of how people make economic decisions refines our understanding of the relationship between income and consumption. The ideas that people are impulsive, that they procrastinate, and that when it comes to making trade-offs between today and tomorrow they can be impatient all mean that some people won’t follow the Rational Rule for Consumers. Instead, some people will simply spend what they have in the moment.

Hand-to-mouth consumers spend their current income; consumption smoothers spend permanent income.

Together, these two factors—psychological limitations and credit constraints—mean that some people don’t smooth their consumption or they don’t smooth it fully. Instead, they live paycheck to paycheck. As a result, their consumption reflects their current income rather than their permanent income. Economists call these folks “hand-to-mouth consumers.” For many people, hand-to-mouth consumption is not so much a choice as a reality—they find it hard to borrow, and rather than save, they spend all their income on necessities. Calling people hand-to-mouth consumers is not a judgment on their lifestyle, but rather it’s intended to describe the different relationship between their consumption and income. Because these folks spend their income as they receive it, their marginal propensity to consume is 1, and it’s the same in response to a change in income that’s temporary or permanent, anticipated or unanticipated.

Total consumption is a mix of hand-to-mouth consumers and consumption smoothers.

The macroeconomy includes both people who smooth their consumption and people who live hand to mouth. The earlier insights that we developed to understand how different kinds of income changes impact consumption were based on the behavior of consumption smoothers. We’ve just seen that hand-to-mouth consumers tend to spend what they have, so their consumption reflects their current income. Let’s take a look at how aggregate consumption across the economy will respond to a change in income, modifying our earlier insights to account for the responses of both consumption smoothers and hand-to-mouth consumers.

Modified insight one:

A temporary change in income will lead to a small change in consumption for consumption smoothers and a large change in consumption for hand-to-mouth consumers. For example, what would you do if you got a $500 tax refund this year? Most people say that they would put most of it in savings or use it to pay off debt, implying that they are consumption smoothers. But others say that they would use the money right away, on any number of things ranging from health care needs to car repairs or vacations. Total consumption reflects the spending decisions of both groups, and so the aggregate marginal propensity to consume out of a temporary income change will be larger the more hand-to-mouth consumers there are in a society.

Modified insight two:

A permanent change in income will lead to a large change in consumption from both consumption smoothers and hand-to-mouth consumers, leading to a large change in total consumption. Indeed, consumption will rise by about as much as permanent income. The marginal propensity to consume out of permanent changes in income remains close to 1, regardless of the mix of hand-to-mouth and consumption smoothers.

Modified insight three:

An anticipated change in income will lead to no change in the consumption of consumption smoothers, but a large change for hand-to-mouth consumers who consume their income as it arrives. The marginal propensity to consume out of anticipated income changes will depend on the share of hand-to-mouth consumers: The larger the share of hand-to-mouth consumers, the higher the marginal propensity to consume out of an anticipated change in income.

Modified insight four:

Learning about a future income change will lead to a large change in consumption from consumption smoothers, who respond to news about future income straight away, but no change from hand-to-mouth consumers, who won’t respond until the extra income arrives. Once again the marginal propensity to consume out of anticipated income changes will depend on the share of hand-to-mouth consumers. However, in this case, the larger the share of hand-to-mouth consumers, the smaller the marginal propensity to consume, since hand-to-mouth consumers do not increase consumption when learning about a future income change.

Modified insight five:

Forecasting changes in consumption depends on the share of hand-to-mouth consumers. Hand-to-mouth consumers spend what they have, so you can forecast changes in their consumption if you know how their income will change. For example, if you know that a tax cut is coming, you can reasonably predict that hand-to-mouth consumers will spend it. Consumption smoothers, however, don’t change their consumption in response to anticipated income changes, so you can’t forecast changes in their consumption. Therefore, your ability to forecast changes in consumption depends on the mix of consumption smoothers and hand-to-mouth consumers.

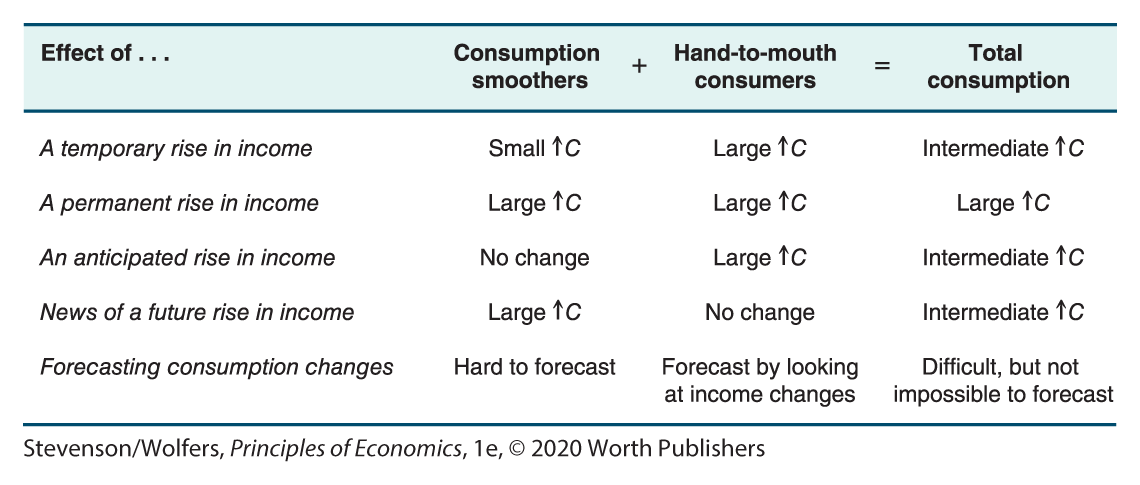

Putting it all together, on average the economy shows some influence of permanent income driving consumption and some influence of current income driving consumption. Figure 9 summarizes the effect of a rise in income on consumption (labelled C) for consumption smoothers in the first column and for hand-to-mouth consumers in the second column. To forecast how aggregate consumption across the economy will respond to the rise in income, you need to account for the responses of both consumption smoothers and hand-to-mouth consumers, and this is shown in the final column of Figure 9.

Figure 9 | Implications of Income Changes for Consumption