26.1 Macroeconomic Investment

Investment is going to be a big part of your life. As an entrepreneur, you’ll invest in starting a new business; as a manager, you’ll invest in new technology; in operations, you’ll invest in more efficient logistics; in accounting, you’ll invest in collecting valuable information. Folks in advertising tell you to invest in your brand, while those in human resources tell you to invest in your workers. In your personal life, you’ll invest in your community, in your friends, and in your romantic relationships. Right now you’re investing in your education by reading about investment. And if that education lands you a job interview, you might invest in a good suit.

Defining Investment

All of these investments involve the following proposition: You incur some up-front cost today in the hope of receiving future benefits. As such, your investment decisions link the choices you make today to your future well-being. In casual conversation people use the word “invest” any time the costs you incur today determine your outcomes in the future. For example, you’ve probably heard people talk about investing in the stock market. When you buy stocks, you are incurring an up-front cost today—giving up your money—in the hope of receiving a future benefit—more money at a later date. But this isn’t what macroeconomists mean when they talk about investment.

Macroeconomists use the word investment to refer to spending on new capital assets that increase the economy’s productive capacity. Because saving money to purchase existing stocks doesn’t add to the productive capacity of the economy, it isn’t part of investment. While we’ll focus on the narrower set of choices that macroeconomists mean when they talk about investment, you can use the analytic framework that we’re about to develop to analyze any decision you face that involves up-front costs and future benefits. Let’s start by exploring what macroeconomists mean when they talk about investment.

Macroeconomic investment refers to spending on capital.

When macroeconomists talk about investment, they mean spending by businesses on new software, equipment, and structures, the accumulation of inventories, and spending on new housing. They include not just physical capital, but also intellectual property.

Macroeconomists focus on this specific definition because macroeconomic investment in capital is a key driver of macroeconomic performance. It’s an important component of spending and a critical ingredient into future production. Figure 1 shows that investment comprises around 16% of total U.S. GDP, which means that investment spending adds up to around $10,000 per person each year.

Figure 1 | Gross Domestic Product

2018 Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Don’t confuse investment and saving.

As you’ve seen, the macroeconomist’s definition of investment excludes a lot of stuff that most people refer to as investments. That’s because people often fail to draw a distinction between saving—which is the money you have left over after paying for your spending—and investment which is spending on new capital that’ll increase the productive capacity of the economy. Putting money in the bank is a form of saving. It isn’t an investment because it doesn’t involve any actual spending on new capital. (As we’ll discuss later in this chapter, saving and investment are related because if your bank lends the money you save to a business which uses it to fund a factory, then that spending will count as investment.) Buying shares in Google, bars of gold, or a block of land doesn’t count as macroeconomic investment because you’re simply buying an existing asset from someone else, without creating any new productive capacity.

Investment adds to the capital stock; depreciation subtracts from it.

The total quantity of capital at a point in time is called the capital stock. Investment is the flow of new purchases of capital that add to this stock. But capital also declines over time due to depreciation, which includes wear and tear, obsolescence, accidental damage, and aging. As a result, this year’s capital stock is equal to last year’s capital stock, less depreciation, plus new investment over the past year. This means that the capital stock rises when new investment exceeds depreciation, but declines when depreciation exceeds investment.

Types of Investment

Macroeconomists break investment into three primary categories shown in Figure 2. The biggest category is business investment and Figure 2 shows you some of its subcomponents as well. The smallest category is inventories and the final category is housing. Let’s take a closer look at each of these types of investments.

Figure 2 | Investment

2018 Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Investment type one: Business investment.

Business investment refers to spending by businesses on new capital assets. This includes spending on equipment (new computers, machinery, and company cars), structures (new offices, stores, factories, and remodeling of existing facilities), and intellectual property (spending on software; on literary, television, movie, and music production; and research and development). These three types of business investment all have one thing in common—they are purchases by businesses that increase the productive capacity of the economy.

Investment type two: Inventories.

Businesses also invest by maintaining inventories of raw materials, work-in-progress, and unsold goods. For instance, the cars you can test-drive at your local car dealership are counted as inventories. Because it’s necessary to keep at least some level of inventories on hand as part of the production process, they’re counted as part of the capital stock. And so an increase in inventories is counted as investment.

The change in inventories is only a tiny share of total investment. But it’s also volatile, because unsold goods build up quickly when sales are weak. As a result, changing inventories account for a big chunk of quarter-to-quarter movements in investment.

Investment type three: Housing investment.

Housing investment refers to spending on building new houses or apartments, as well as improvements to existing housing. It includes both homes that you buy to live in and housing that you plan to rent out.

Buying an old home doesn’t count as investment—but spending on renovations does.

Housing investment is a bit different from business investment, because when you live in a house, it doesn’t generate revenue. But the opportunity cost principle reminds you that your family home could be used to generate rental income. Thus, building a new family home counts as investment because it’s an increase in the stock of capital that increases the economy’s productive capacity—increasing the economy’s capacity to generate rent. For similar reasons, remodeling a home is an investment. But sales of existing homes simply transfer ownership from one person to another, and hence don’t count as investment because they don’t increase the economy’s productive capacity.

Investment Is a Key Economic Variable

While investment only accounts for around one-sixth of all spending, it’s a category that economists pay close attention to because it has an extraordinarily important impact on the economy.

Investment drives the business cycle.

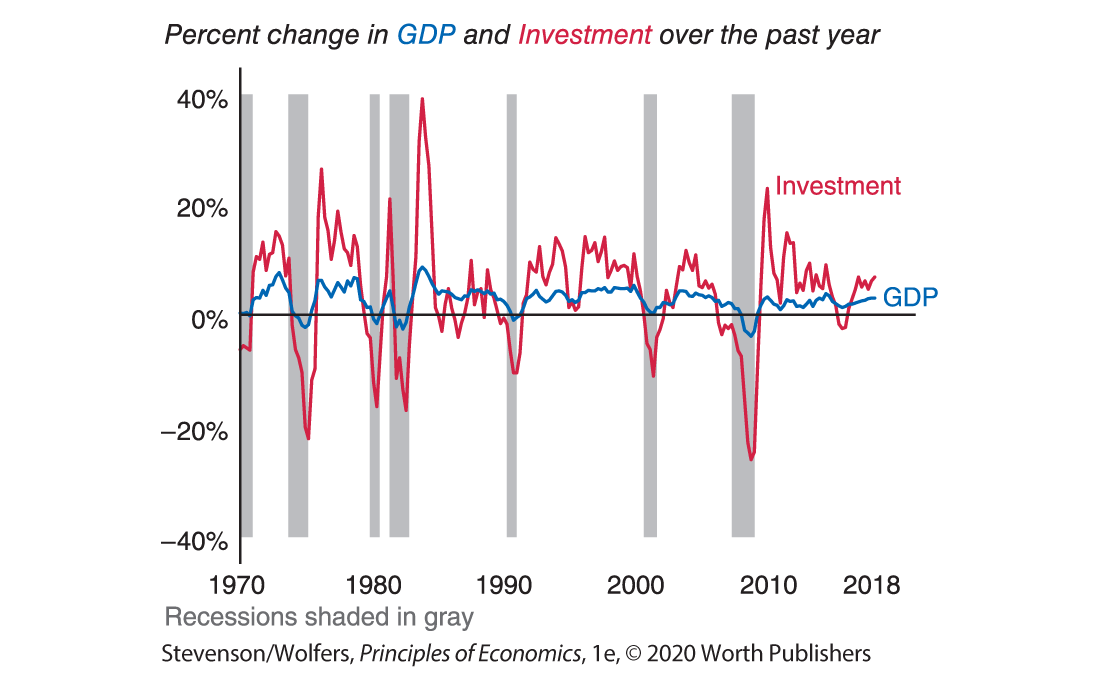

Investment fluctuates dramatically as business conditions change, so it plays an outsized role in driving the ups and downs of the business cycle. Figure 3 shows the relationship between the annual percent change in GDP and investment. A recession might lead GDP to decline by 2% from the previous year. In contrast, investment might decline by more than 20% from the previous year, as it did in 2009. Likewise, a strong economy might lead GDP to grow by 4%, but it could cause investment to grow by ten times as much. In short, investment changes more from year to year than GDP does.

Figure 3 | Investment Drives the Business Cycle

Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Investment is very sensitive to business conditions partly because managers can easily delay or cancel expansion plans. Moreover, because investment decisions are forward-looking, they’re extremely sensitive to expectations about the future state of the economy. Investment is also sensitive to financial sector conditions because businesses often have to get a loan to fund their investments. It’s often said that once you figure out what drives investment, you’ve figured out much of what drives the business cycle.

Investment changes quickly, but the capital stock changes slowly.

Today’s capital stock is the accumulation of investments made over many previous years. As a result, even though investment—the flow of new spending on physical capital—often fluctuates quite dramatically, the capital stock—which is the stock typically of physical capital—only moves slowly. Indeed, the capital stock typically rises gradually over time, and it doesn’t change much from year to year. As such, the capital stock provides a relatively stable link between last year’s economy and today’s economy.

Investment is a key driver of long-term prosperity.

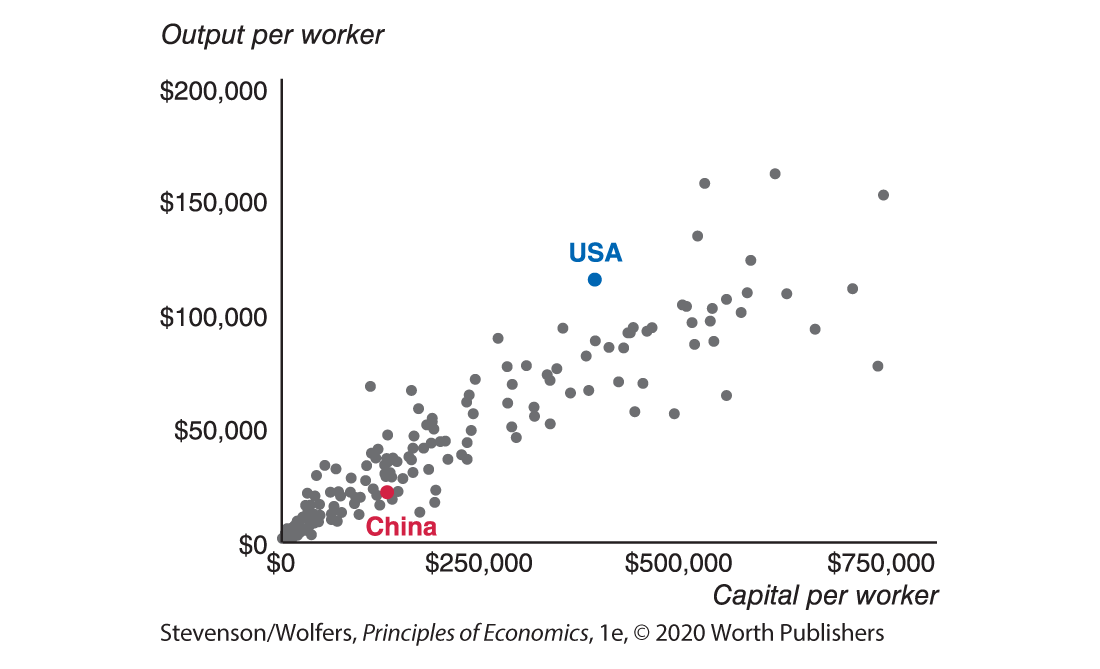

Investments in capital are an important source of differences across countries in productivity and hence prosperity. The more capital—tools, machines, and computers—your workers have to work with, the more output they’ll be able to produce. Indeed, Figure 4 shows that countries with more capital per worker typically have more productive workers, producing more output per worker.

Figure 4 | Countries with More Capital per Worker Produce More Output per Worker

2017 Data from: Penn World Tables 9.1.

Education is another big driver of worker productivity, but investments in human capital—that is, going to school and college—aren’t counted in macroeconomic investment. If they were to be included, then the role of investment in making some countries more productive, and therefore more prosperous, would become even more dramatic.