27.1 Banks

Phil Knight was a track enthusiast who ran for the legendary University of Oregon Ducks. He was also a business student with a paper to write for an entrepreneurship course. So he wrote about what he knew: running shoes. At the time, Japanese cameras were starting to take market share from the once-dominant German camera companies. In his paper, he argued that the time was ripe for Japanese-made shoes to challenge the German athletic giants such as Adidas and Puma. When he presented the paper in class, his fellow students were bored. No one asked any questions, but at least he got an A.

The original Nike logo design.

Phil couldn’t stop thinking about his big idea. After graduation, he decided to give it a try. He visited a Japanese shoe factory, presenting himself as an American tycoon. His ruse worked, and he landed a deal to sell Japanese athletic shoes in the United States. When his old track coach saw the shoes, he was so impressed that he asked to become Phil’s business partner. Initially they called the company Blue Ribbon Sports. Later on, they changed it to Nike.

Phil bought his first shipment of shoes with a loan from his father. He quickly sold his first shipment, so for his next shipment he did what many other small businesses do: He turned to his bank for a loan. The First National Bank of Oregon lent him enough money to buy nine hundred pairs of shoes.

Banks are an important funding source for many of life’s major investments. Banks provide car loans to fund your car purchase, home loans to help you buy a home, and small business loans to help you start or expand your business. And so our first task in this chapter is to explore just what it is that banks do.

What Do Banks Do?

This is not how banks work.

When you put your money in a bank, your bank takes your money and puts it to work by lending it out, perhaps to provide a loan to a student, a home loan to a young couple, or short-term funding for Nike. Putting your money to work is how the bank earns itself a profit.

Banks make money by charging higher interest rates than they pay.

When you deposit your money in the bank, it is not storing your money for you. Instead, it’s borrowing money from you. This changes how you think about your relationship with your bank: As a saver, you’re the lender, and it’s the borrower. Your bank borrows from you so that it can then lend that money to others, and in the process both you and the bank make money.

The price your bank pays to borrow your money is the interest you receive. If you earn 2% per year interest, then depositing $100 in the bank now means that a year from now, you’ll have $102 in your account. Your bank makes money by lending that money out to someone else at a higher interest rate. If it charges 6% per year interest on its loans, then someone who borrows $100 will owe them $106 a year later. At that point, the bank owes you $102, but borrowers owe it $106, meaning that the bank made $4.

Your bank is just a middleman; it’s buying and then selling a somewhat unusual product: the right to use $100 for the next year. Just like the middleman in any other business, it buys its products at a low price (the 2% interest rate), and then sells it at a higher price (the 6% interest rate).

People willingly pay for this because banks provide valuable services. There are five important functions that banks provide. Let’s look at them one by one.

Function one: Banks pool savings from many savers.

Your bank pools the savings of many savers and lends that pool of savings to a specific borrower. For savers, this is a valuable service because it means that even if you only have $100 in savings you can earn interest on the money, even if that amount is too small for you to efficiently find someone who needs to borrow it. The flip side is that it’s also easier for borrowers to go to one bank than it is for them to try to borrow from dozens of individual lenders. Imagine trying to directly approach dozens of people, asking to borrow their savings, when you need a car loan.

Function two: Banks spread the risk of lending money across many borrowers.

Banks also make lending your money much less risky because they lend to a diverse array of borrowers. Your bank doesn’t lend all your savings to Nike or any one borrower. Instead, your bank pools money from thousands of savers and lends that money to thousands of borrowers. Effectively, you’re lending a dollar of your money to Nike, a nickel to a local small business, a dime to your neighbor’s home loan, and so on. The more diverse this portfolio of loans is, the less risky it is.

Function three: Banks solve information problems.

Your bank is also an important information intermediary. It doesn’t lend your money out to just anyone. Before a borrower can get a loan, your bank will delve into their credit history, check on their assets, and examine their debts. Banks are particularly effective at figuring out who to lend to because they’re privy to the financial histories of their customers, and they use this to identify which borrowers will be able to repay their loans.

EVERYDAY Economics

Build a good credit score

One way that banks decide who to lend money to, and what interest rate to charge, is by checking a borrower’s credit score. Whether you know it or not, you probably have one. It summarizes everything that credit bureaus have learned by tracking your financial life. Your credit score (sometimes called your FICO score) is like a GPA for your financial life, and it has far-reaching consequences. So it’s a wise idea to take care of your credit score by following these good practices:

- Pay your bills on time. A missed payment will stay on your credit report for seven years.

- If you miss a payment, catch up as soon as possible.

- Develop a history of using credit responsibly. Ironically, not having a credit card doesn’t help—you need to show that you can be responsible when you have credit.

- Once you have a credit card, pay off the full balance every month.

- If it looks like you might be getting into trouble, call the lender. Often, they will be willing to work with you to negotiate an arrangement.

- You have the right to see the data that goes into your credit report and to demand corrections. You can check it for free at www.annualcreditreport.com.

Function four: Banks provide payment services.

The other reason that you want a bank account—beyond earning interest—is that it makes your economic life a lot simpler. You’ll likely find it easier and safer to have your pay deposited directly into a bank account than to go and collect cash. Similarly, you might find it easier to pay your rent electronically, pay your bills online, send money overseas with a bank transfer, and shop online using your credit card. In each case, your bank is providing you with payment services that are often more convenient than using cash.

Function five: Banks create long-term loans from short-term deposits.

There’s an interesting tension at the heart of banking: Your bank borrows money from savers like you who want to be able to withdraw their funds whenever they want. But your bank then lends this money to borrowers who don’t have to repay their loan on demand. Instead, borrowers tend to repay over a fixed (and long) period of time. For example, home owners might take out a loan in which they agree to a 30-year repayment plan.

The fact that you want to be able to wake up any day and take your money out of the bank means that effectively you loan the bank money overnight. If you don’t withdraw it on any given day, then you are loaning it for another night (and thus giving yourself the option of withdrawing the money the next day). In other words, by making your funds available to you on demand, your bank effectively gets its money from taking short-term (overnight) loans from people like you. But it needs to use those funds to make longer-term loans. What it’s doing is called maturity transformation—using short-term loans to make long-term loans. Maturity transformation ensures that investors can fund long-term projects, even when no individual savers are willing to make a long-term loan.

While banks typically successfully engage in maturity transformation, it can cause problems. In fact, it creates a risk that can lead the whole system to come crashing down. Let’s see how.

Bank Runs

If your bank doesn’t just store your money in its vault and leave it waiting for you, how do you know that your money will be there when you want it? The answer: You don’t.

Your bank makes money by lending money. That means that it doesn’t keep your money in a bank vault waiting for you. Of course, your bank knows that some people will withdraw their cash, so it keeps enough cash on hand to meet a typical level of withdrawals, plus a bit extra just in case. But it can’t keep it all, because if it did, it wouldn’t be able to pay you interest or pay its employees.

A bank run occurs when many customers try to withdraw their savings at the same time. If a much larger number of customers than usual try to withdraw their savings at the same time, your bank might not be able to pony up your money. When this happens, it can cause a bank to collapse.

Bank runs can cause a bank to collapse.

When there’s a bank run, run.

On a typical day, few savers will make a withdrawal and banks have plenty of money on hand to give them when they request it. But what makes a day typical? Well, it turns out that a day is typical if most people believe that it is a typical day.

If you believe that tomorrow will be a typical day, then you can go to bed confident that if you need your money, your bank will be able to pay you since your bank can pay everyone who withdraws their money on a typical day. Given this, you’re happy keeping your savings in the bank if you don’t need the cash.

If you believe that tomorrow will not be a typical day—meaning you expect more people than normal will try to withdraw their money—then you shouldn’t feel so reassured. Perhaps you’ve heard that some people are so worried about your bank’s financial health that they’re planning to withdraw their savings tomorrow. You realize that an abnormally large number of withdrawals might clean your bank out of cash, and so you can’t afford to wait to withdraw your money. Your best response is to run—don’t walk!—to the bank and withdraw your savings before other customers beat you there. If other customers follow similar logic—and I believe they will—then they’ll also run to the bank.

In fact, this was the story of Washington Mutual, a bank that was suffering from having made a large number of home loans that were struggling. In September 2008, customers got wind of the bank’s financial trouble, and many ran to the bank to take their money out. Others raced to the bank simply to beat those who were making panicked withdrawals. Within 10 days customers had withdrawn $16.7 billion from their checking and savings accounts. These demands left the Washington Mutual unable to conduct day-to-day businesses, and the bank was taken over by the government.

A bank run is likely whenever people believe that a bank run is likely.

While Washington Mutual was suffering from poor financial health, the challenge for banks is that a bank run can happen even when they are financially healthy. In fact, almost anything can trigger a bank run. For example, more than 10,000 Latvians rushed to the bank to withdraw their money after a false rumor spread on Twitter that the bank was planning on shutting down operations in Latvia. In this sort of panic, it can be rational for you to pull your money out of the bank even if you know the rumor is untrue.

If you believe that others are going to run to withdraw their savings, then your best response is to try to get there first—before the bank runs out of money. And this is your best response whether they’re doing this for good reasons (the bank is in financial trouble) or crazy reasons (it’s a lunar eclipse) or for a Twitter-based rumor of bank closure that you know is false. And if other people believe that you’re going to run to the bank, their best response is to try to get there first, no matter the reason.

This is the interdependence principle at work—your best choice depends on what others will do, and their best choice depends on what you will do. In normal times, this interdependence means that you’re happy keeping your money in the bank, as long as others are happy keeping their money in the bank. But it also means that there’s the possibility of a self-fulfilling panic: You’ll panic because you’re worried that others will panic, and they’ll panic because they’re worried you’ll panic.

Bank runs can be contagious.

Because you panic if someone else panics, it’s also easy to see how bank runs can be contagious. For example, on September 15, 2008, a financial institution called Lehman Brothers collapsed. The collapse of Lehman Brothers increased concern about Washington Mutual, fueling a bank run that led to Washington Mutual’s collapse on September 25. As a result, depositors at other banks started looking hard at their banks, wondering if they could be next. Wachovia Bank found itself in this position as depositors withdrew deposits over the weekend following the collapse of Washington Mutual. Wachovia was forced into a fire sale—a quick sale due to financial distress—selling itself to Wells Fargo over the weekend to ensure its branches could open on Monday with enough funding to meet depositors’ demands. As the CEO of Wachovia put it: “You could go from being OK … to in trouble in a matter of days. I don’t think people understand how quickly events unfolded.”

Deposit insurance makes bank runs much less likely.

While the United States experienced a few bank runs in 2008, they have been quite rare throughout your lifetime. But this wasn’t always true. Bank runs were such a big problem in the Great Depression that in the early 1930s over one-third of all existing banks failed. In response, the federal government introduced deposit insurance, which effectively guarantees that you’ll always get your savings back, even if your bank collapses. This ensures that you won’t lose the money you deposit in the bank. But this insurance only covers up to $250,000 in an account.

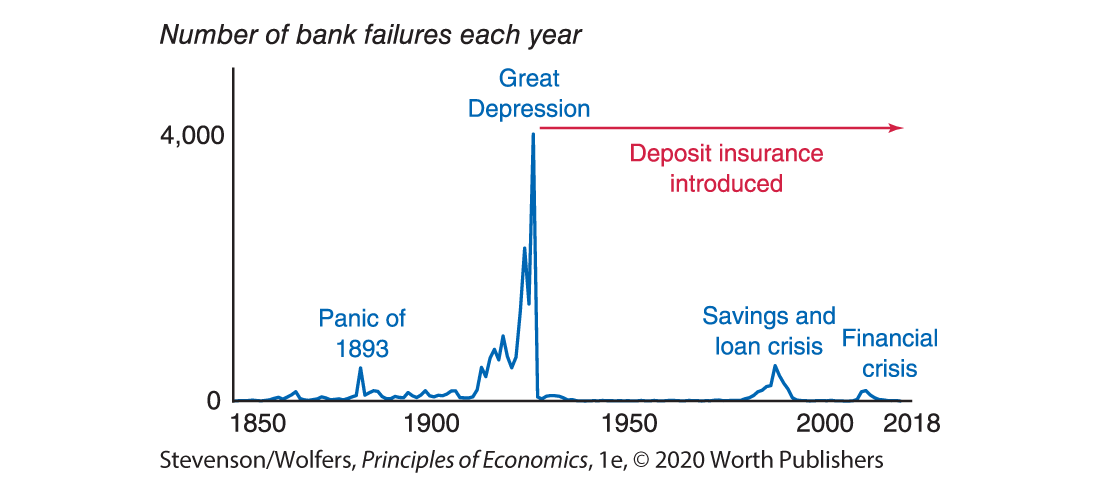

Deposit insurance is designed to break the interdependence that leads to self-fulfilling panics. When you have deposit insurance, you know that your savings are safe, no matter what other people do. Even if others withdraw their money from the bank, you don’t need to try to beat them to the bank, since you know that you’ll ultimately get your money back. Deposit insurance is a simple idea, but it really works. Figure 1 shows that since the government created deposit insurance in 1934, U.S. bank failures have become incredibly rare.

Figure 1 | Deposit Insurance and Bank Failures

Data from: Historical Statistics of the United States and FDIC.

Shadow Banks and the Financial Crisis

At this stage, you might be wondering: If deposit insurance works so well, why did the United States suffer a major financial crisis in 2008? One answer is that not all financial firms are banks and only banks are covered by deposit insurance.

Shadow banks perform banking functions, but aren’t regulated as banks.

Shadow banks are pretty similar to banks—they get their funds from depositors who can withdraw their money at any time, and they use those funds to make long-term loans to investors. But because they’re not officially called banks, they’re not regulated like banks, which frees them up to rely on innovative and risky funding. It also means that there’s no deposit insurance, and that makes them vulnerable to bank runs. That’s the short-story version of what happened in 2008. Large financial firms such as Bear Stearns were shadow banks, and when their depositors lost faith in them, they withdrew their money, causing a (shadow) bank run.

Fire sales can cause shadow bank runs to spread.

The problem quickly spread. A shadow bank facing a bank run has to sell its assets quickly in order to repay its depositors. Putting billions of dollars of financial assets up for sale at once floods the market, pushing the price of those assets down. Then the interdependence principle kicks in: Because other shadow banks hold similar assets, a fire sale of assets by one shadow bank in trouble reduces the market value of other shadow banks’ assets. And that reduction in market value makes the customers of other shadow banks more nervous, leading to further bank runs. As more shadow banks go belly up, there are more fire sales, and the problem spreads like a virus.

Shadow banks are opaque.

The insurance company AIG is a shadow bank that got in trouble and needed a bailout in 2008.

There’s another problem in all of this: The shadow banking system is incredibly opaque, and so when one financial institution can’t pay its debts, it’s hard to know who will be hurt. Unknown interdependencies can make small problems balloon into big ones. It’s a bit like knowing that a small share of the meat supply is infected with illness-inducing bacteria, but not knowing which particular shipments or suppliers are affected. When this happens, millions of people stop eating meat rather than risking illness.

Bad loans are the financial equivalent of bacteria. Depositing money with a shadow bank infected with bad loans may put you in financial distress. If you don’t know which shadow banks are infected and there is no deposit insurance, you won’t want to lend money to any of them. That’s how a relatively small number of bad loans in 2008 caused lending to decline sharply, which then sparked a major recession.

Okay, that completes our tour of banks and shadow banks. Let’s now turn our attention to another way to borrow money: the bond market.