27.2 The Bond Market

Fast-forward from Nike’s humble beginnings to 2016, and you’ll find that it’s grown to become one of the world’s largest companies. Every investment it made seemed to make the company more valuable. Buoyed by this success, senior management decided they had to invest more, particularly in improving Nike’s computing infrastructure and global distribution network. It’s worth doing, but it’s also expensive. Nike’s financial team crunched the numbers and figured they needed another $1 billion to fund this new investment.

What Does the Bond Market Do?

A bond certificate.

When you want to borrow money, you probably go to the bank. But what if you’re Nike, looking for a cool billion? I’m afraid your local bank manager just isn’t prepared to deal with a loan that big. Instead, Nike did what many other corporations do—and also what the government does when looking for a loan. It turned to the bond market. The simplest way to think of the bond market is that it’s where the big dogs go to borrow the big bucks.

A bond is just an IOU. When Nike issued its bonds, it borrowed a billion dollars and promised to pay it back in the future, with interest. The bond is just the piece of paper recording the terms of the IOU. When you buy a bond, you give Nike cash, and it gives you a piece of paper, promising to pay you back.

That piece of paper is important, though, because it spells out the terms of the loan. It records the borrower (called the issuer, which is Nike), how much Nike has to repay at the end (the principal, which is $1 billion), when the loan must be repaid (the maturity date, which is November 1, 2026), and the interest it has promised to pay along the way (these are called coupons, and Nike promised to pay 2.375% interest per year).

The bond market is a big deal. As of 2016, the total quantity of outstanding bonds issued in the United States was close to $39 trillion, or a bit more than $100,000 per American. Many students believe that they don’t own any bonds. Perhaps that’s true, at least while you’re a student. But you’ll probably go on to a career that includes a retirement plan, and your retirement plan will likely invest some of your money in bonds. This means that in a few years, you’re going to be a big player in the bond market, albeit somewhat indirectly.

So what purpose does the bond market serve? The bond market performs four key functions.

Function one: The bond market channels funds from savers to borrowers.

The bond market provides an alternative to banks; it’s an alternative market where companies can borrow the large sums of money they need to fund their investments, and savers can lend the funds they aren’t using. As such, it channels unused resources from savers (like you) to borrowers (like Nike).

While the stock market tends to hog the headlines, in fact bonds are a much bigger source of corporate financing. In 2016, companies raised around $250 billion by issuing new stock, but they raised nearly $1.5 trillion from issuing bonds. This equates to a bit less than $1,000 per American each year in new stock issues, and about $5,000 per American in new bond issues.

Function two: The bond market funds government debt.

It’s not just companies like Nike that borrow by issuing bonds—so do governments. In fact, the U.S. federal government is the biggest player in the bond market: It has borrowed over $15 trillion by issuing bonds. Whenever you hear about government debt, realize that it borrowed all that money by issuing bonds. Beyond the federal government, state and local governments (and even school districts) also borrow money by issuing bonds. Foreign governments also borrow money by issuing bonds.

Function three: The bond market spreads risk.

Instead of issuing just one $1 billion bond to one person, Nike issues thousands of bonds in denominations as small as $1,000. This way, even if no one individual has a spare billion to lend to Nike, thousands of investors may be willing to each make a smaller loan. By making it easy to spread borrowing across many lenders, bonds spread the risk that Nike won’t repay its loan across many lenders.

As an investor, even if you had a billion dollars to invest, you probably wouldn’t want to lend it all to Nike. Instead, you should diversify your portfolio, investing small amounts in bonds issued by many different companies. By not holding all your eggs in one basket, you’ll make sure that if Nike collapses, you won’t lose all your savings.

Function four: The bond market creates liquidity.

Trading bonds creates liquidity.

The problem with lending someone money for 10 years is that you might suddenly discover you need the cash before the loan is due. Fortunately, you can sell your bond to other investors in the bond market. Because there are many buyers, you’ll usually get something close to a fair price. That is, the bond market creates liquidity, which is the ability to quickly and easily convert your investments into cash, with little or no loss in value.

In this way, the bond market—like banks—creates long-term loans from short-term loans. This maturity transformation is done through the ability to resell bonds in the bond market. When you sell your bond to someone else, you get your money back—the cash value of your bond—and they take over the loan, getting the future interest payments and the principle repayment on the maturity date.

Evaluating Risks

Bonds have the advantage of clear terms: You know the interest rate you’ll be paid, the date at which you’ll be paid back in full, and these promises will be honored as long as the company hasn’t gone bust. But there are some specific risks that you face. The first is the chance that the company goes bust: default risk. The second is term risk and the third is liquidity risk. Let’s explore each in turn.

Risk one: Default risk is the risk of not getting paid.

One risk of lending people money is that they won’t repay their loans, and this risk also exists for bonds. If Nike goes bust, it may not have enough money to repay people who bought Nike bonds. The risk that you won’t be repaid (or won’t be repaid in a timely fashion) is called default risk. Companies like Fitch, Standard and Poor’s, or Moody’s evaluate companies and assign credit ratings, which are like credit scores for businesses. Because it’s difficult for each investor to assess Nike’s chances of default, investors rely on these credit ratings to assess default risk.

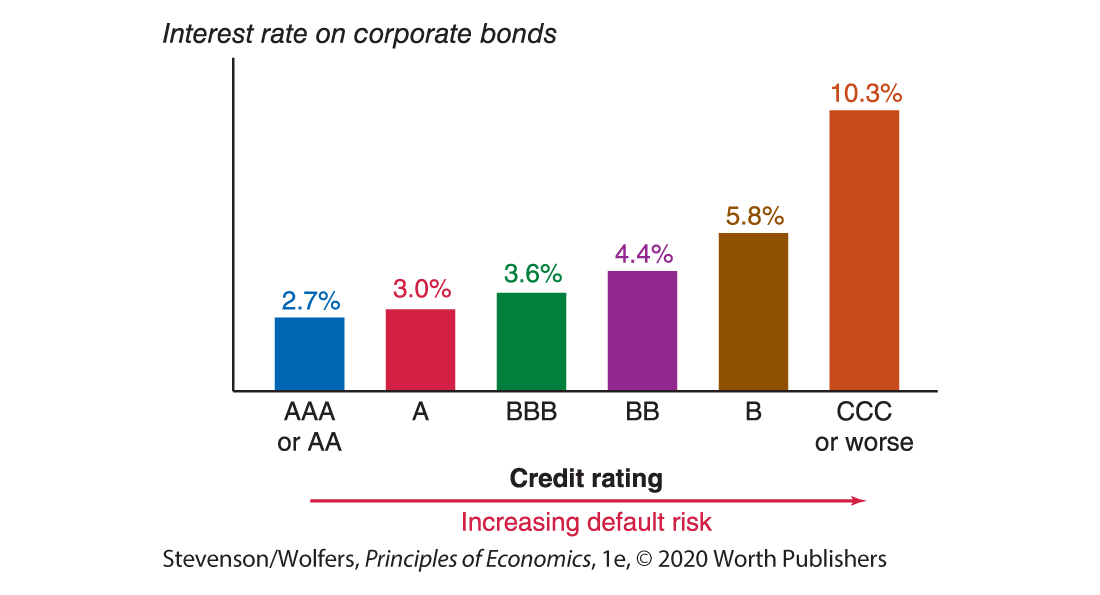

A rating of “AAA” is the highest possible rating, meaning the company has an extremely strong capacity to repay its debt. Nike’s $1 billion bond issue earned a rating of “AA–,” which is not quite perfect but still good enough to suggest it has a very strong capacity to repay its debt. Figure 2 shows that the worse the rating, the higher the interest rate: as the default risk rises, lenders demand a higher return in order to take on the additional risk that the loan won’t be paid back.

Figure 2 | Interest Rates Rise with Default Risk

Data from: Bloomberg.

Risk two: Term risk arises when there’s uncertainty about future interest rates.

The opportunity cost principle reminds you that tying up your money comes with an opportunity cost—you could invest that money in the bank and earn interest on it. The problem is that when you buy a bond, you don’t know what future interest rates will be, so you are taking a risk as to what the opportunity cost will be over the term of the bond. The investors who agreed to loan Nike money for a term of 10 years at 2.375% per year were hoping that the opportunity cost over the next 10 years would be less than 2.375%. If interest rates shoot up to 4%, they are stuck earning only 2.375%, and the forgone opportunity to earn a bigger return can be an expensive opportunity cost.

The risk that arises from uncertainty about future interest rates is called term risk because the risk is connected to the length, or term, of the loan. The more uncertain you are about future interest rates, the greater this risk is. The longer the term, the more interest rates might change, and so the higher the term risk. Nike borrowed $500 million over 30 years and faced a higher interest rate (3.375%) than it had when it borrowed $1 billion over 10 years (2.375%). Term risk explains why it had to pay this higher rate.

Risk three: Liquidity risk arises when your bond will be hard to sell.

Another risk in lending out your money is that you might end up needing those funds yourself. If your money is in the bank, you solve this by just making a withdrawal. But to “withdraw” your money from a bond, you have to sell it. While the bond market creates liquidity, there is a risk that you won’t be able to quickly find a buyer for your bonds. Liquidity risk refers to the risk that if you need to sell an asset quickly, you may not be able to get a good price for it.

Billions of dollars of federal government bonds are traded each day, and so these involve very little liquidity risk. But it can be harder to quickly find a buyer for a bond issued by small company, making liquidity risk a much bigger deal.

U.S. government bonds are the safest investment.

Putting all of this together, you’ll discover that the safest investment you can make is to buy bonds issued by the U.S. government, which are often called Treasuries. They’re considered safe because the U.S. government can always pay its debts simply by printing more money. (However, there remains a political risk that Congress might choose not to make debt payments in a timely fashion.) U.S. government bonds are also the most heavily traded bonds in the world—around $500 billion in Treasuries are traded each day!—and so they carry basically no liquidity risk. And a short-term loan carries almost no term risk, which is why the interest rate on short-term loans to the federal government is often described as a risk-free interest rate.

The cost of all of this safety is that lower risk comes with a lower reward, and so the interest rate on U.S. government bonds is lower than the interest rate on other bonds. That’s why the U.S. government can borrow money at a lower interest rate than any other organization. Of course, it doesn’t have to be this way: When investors became concerned about whether Greece could repay its debts in 2012, the interest rate on Greek government bonds rose to over 25%.

If you’re a company looking to raise money, you don’t have to turn to banks or the bond market—you also have the option of issuing stock instead. So let’s turn our attention to the stock market.