28.5 The Balance of Payments

It’s time to draw together the threads of this chapter. We began by noting that the American economy is linked to the global economy through international trade and global financial flows. We then explored the role that these play in shaping the supply and demand for U.S. dollars, and analyzed how the real exchange rate also affects imports and exports. Our final task is to describe how to keep track of all of this using the balance of payments, which summarize a country’s transactions with the rest of world.

The Current Account and The Financial Account

The balance of payments tracks two important sets of transactions. The current account tracks how much income crosses national borders each year, while the financial account tallies up financial flows across borders.

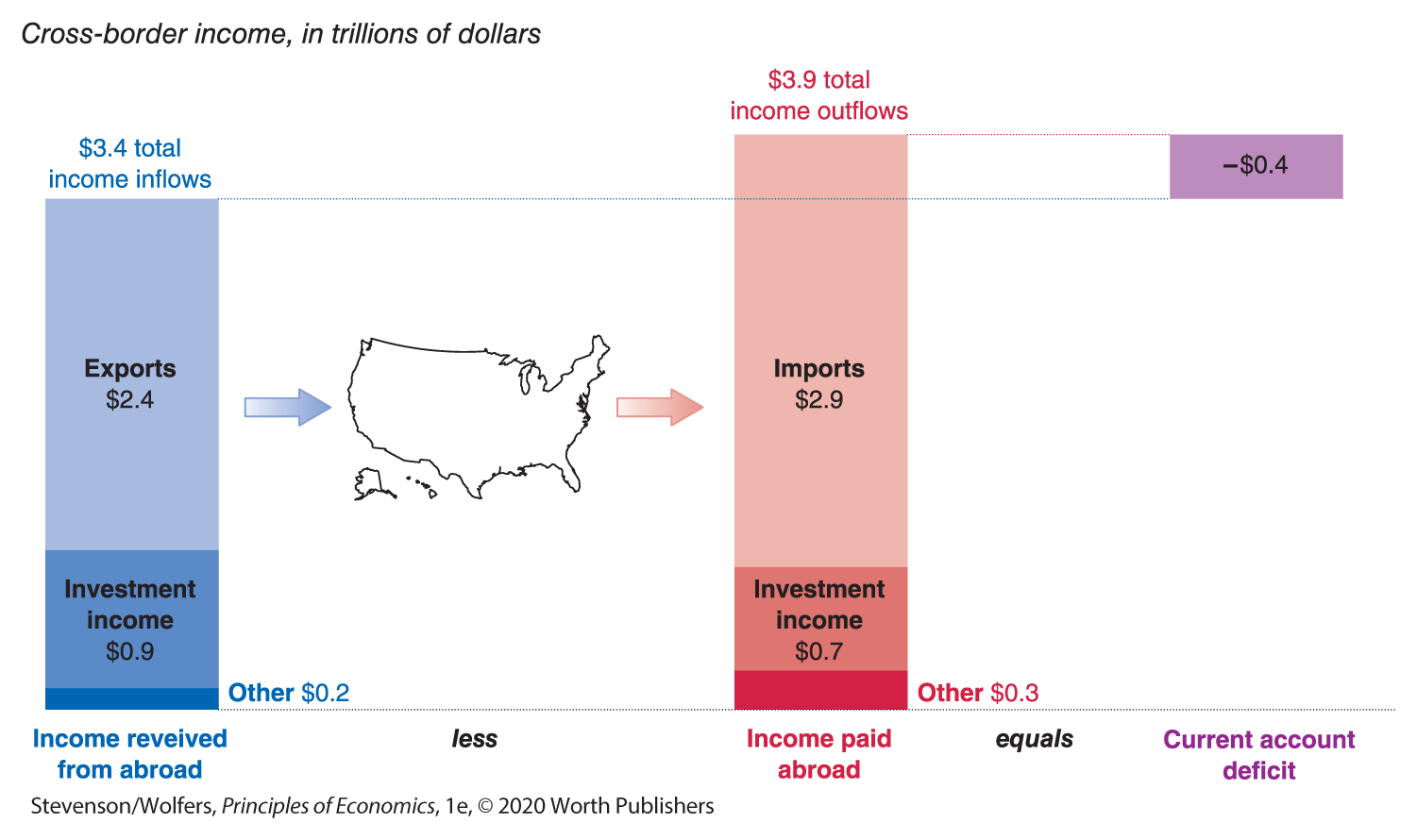

The current account tallies up income flows into and out of a country.

The current account balance measures the difference between the income that Americans receive from abroad, and the income that Americans pay to people abroad. The current account tracks all income flows with the rest of the world, and so it’s a broader measure than net exports, which only tracks the income earned from exports less the income paid for imports.

The blue bar in Figure 15 shows the income that Americans receive from abroad. The largest source of income from abroad comes from selling exports, such as the income the Mathisons earn from selling their apples to Japanese buyers. The next most important source of income is the investment income that Americans earn on their foreign assets.

Figure 15 | The Current Account

Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The red bar in Figure 15 shows the income that Americans pay to people abroad. The largest source of this income is the money that Americans spend buying imports from abroad. Investment income that foreigners earn on the assets they own in the United States is the next largest source. This includes the profit that Toyota’s American factories generate for their Japanese owners, the annual interest that American borrowers pay to foreign banks that have loaned them money, and the dividends that American companies pay to their foreign shareholders. In addition, there are some other smaller income flows.

All told, in 2017, Americans received $3.4 trillion in income from abroad, and made $3.9 trillion in income payments to foreigners. As a result, the United States ran a current account deficit of $0.4 trillion. To put this in more human terms, on average, each American received roughly $1,500 less income from abroad than they paid to foreigners.

Notice that the current account doesn’t count the sale of assets as income. That’s because when you sell $10,000 of your stock in Ford to a foreigner, you’re not really generating any income: You’re sending someone a financial asset worth $10,000 (your stock certificate), and in return, they’re sending you a financial asset worth $10,000 (the cash they hand over). A transfer of existing assets doesn’t generate any new income, which is why it’s not part of the current account. However, these financial flows are important because they reflect the changing international ownership of assets, and so our next task is to see how we keep track of them.

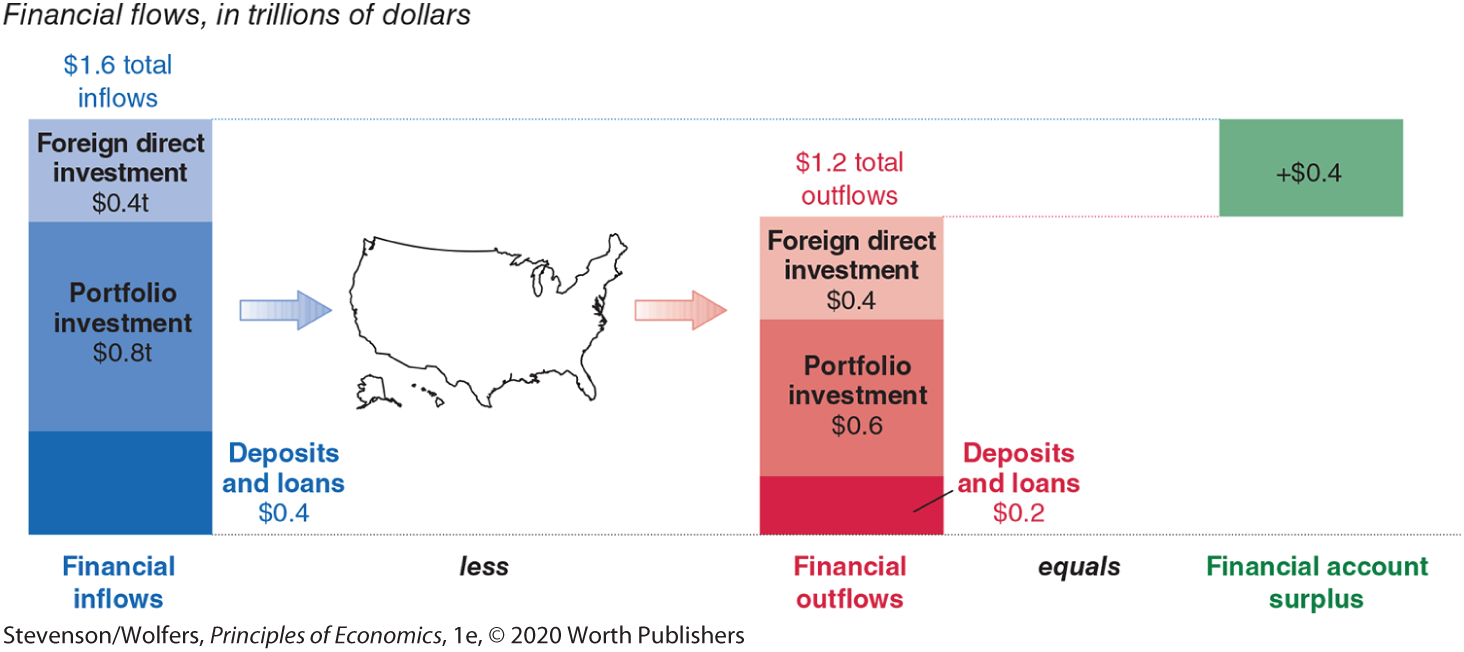

The financial account tallies up changes in the ownership of assets.

The financial account tracks incoming and outgoing foreign investments. The financial account balance measures the difference between financial inflows and financial outflows. Figure 16 shows that in 2017, financial inflows totaled $1.6 trillion, while financial outflows were $1.2 trillion. This yields a financial account balance of a $0.4 trillion surplus, which means that foreigners invested $0.4 trillion more in the United States than Americans invested abroad. In other words, foreigners bought $0.4 trillion more American assets than Americans bought foreign assets.

Figure 16 | The Financial Account

Data from: Bureau of Economic Analysis.

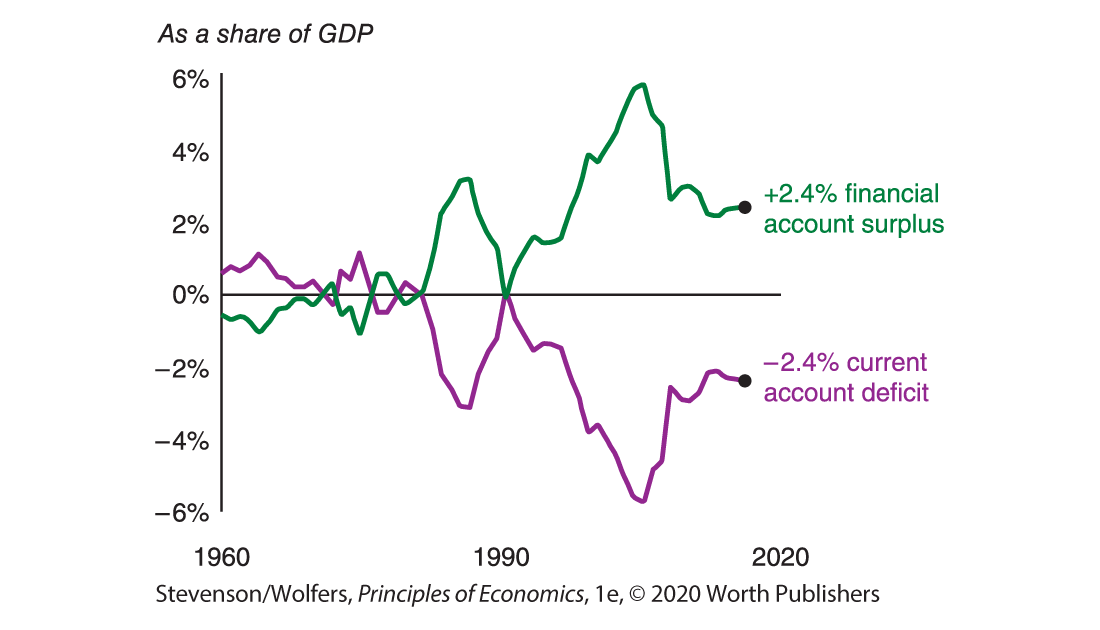

The United States has run a current account deficit and financial account surplus for decades.

The purple line in Figure 17 shows that the United States has run a persistent current account deficit since the early 1990s. This deficit means that the income that Americans have paid foreigners has exceeded the income that Americans have earned from abroad. The green line shows that through this same period, the United States has also consistently run a financial account surplus, meaning that each year more funds have been invested in the United States from abroad than Americans have invested overseas.

Figure 17 | Financial Account and Current Account Balances

Data from: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

Put these two pieces together, and the current account deficit describes a net outflow of funds that is exactly offset by the net inflow of funds from the financial account surplus. This connection is not a coincidence: You can think about the current account deficit as the gap between the income and the expenditure of Americans. The financial account is how we pay for it.

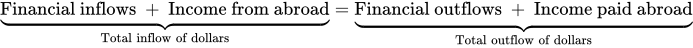

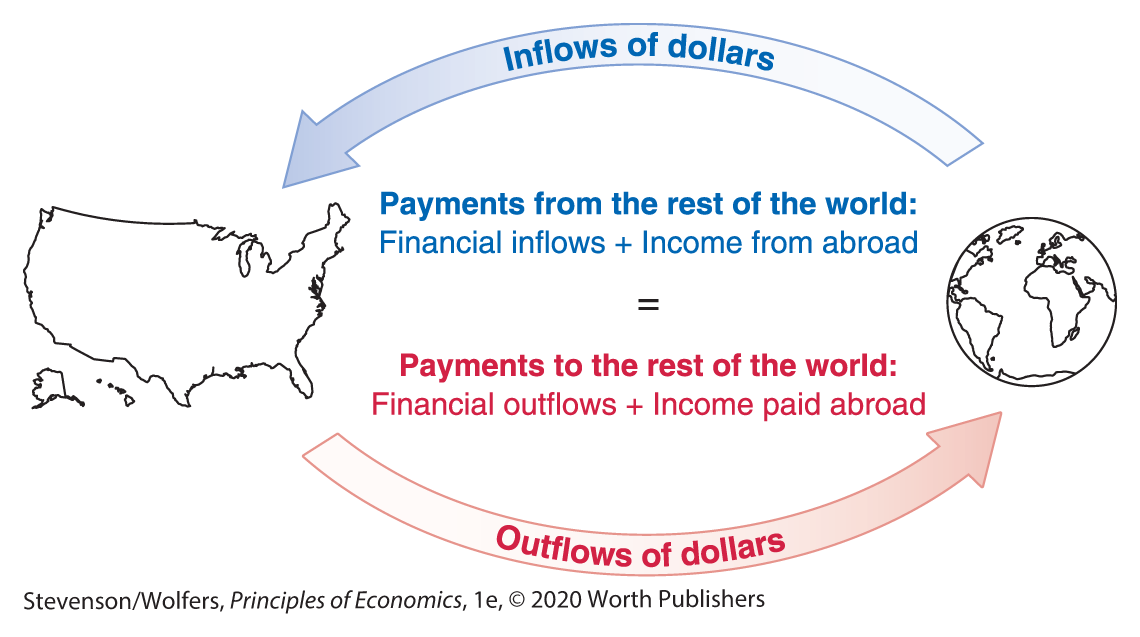

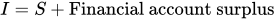

Inflows of dollars must equal outflows of dollars.

This close connection between the current account and the financial account balance reflects a deeper truth: You can only buy a dollar if someone sells it to you, just as you can only sell a dollar if someone buys it from you. And so inflows of dollars from abroad (which requires buying dollars) must be equal to the outflow of dollars (which requires selling them).

Figure 18 shows that the total inflow of dollars (which reflects both financial inflows and income received from abroad) must be equal to the total outflow of dollars (which reflects both financial outflows and income paid abroad). And so it follows that:

Figure 18 | Inflows Equal Outflows

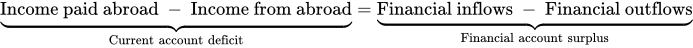

Equality between inflows and outflows implies equality between the current and financial accounts.

If we take this inflows-equals-outflows equation and do a quick bit of rearranging, we get the following insight:

The left-hand side of this equation is the current account deficit, while the right-hand side is the financial account surplus. It says that the current account deficit must always be matched by an equal financial account surplus. It follows from a simple idea: The uses of cash must be equal to the sources of cash—and the current account describes the uses of cash, while the financial account describes its sources.

EVERYDAY Economics

The global consequences of buying a kimono

The US$100 you send to pay for this kimono will eventually return to the United States.

For every international action, there’s an equal and opposite reaction which ensures the current account deficit and financial account surplus remain equal. To see this, let’s track a $100 bill after you spent it buying imports. Perhaps you logged on to Etsy and paid a Japanese artisan US$100 to make you a kimono. Because your new kimono is an import, it added $100 to the current account deficit. What’s the equal and opposite reaction?

It depends on what the Japanese artisan does with your $100 bill. They really only have three possibilities:

- They might invest it, buying $100 worth of American assets, which would boost U.S. financial inflows by $100. In this scenario your initial purchase, which added $100 to the U.S. current account deficit, is exactly offset by a foreign investment which adds $100 to the U.S. financial account surplus, maintaining their equality.

- They might buy $100 of American goods and services. In this case, your initial purchase boosted U.S. imports by $100, and their purchase boosted U.S. exports by $100, and in total, the U.S. current account deficit is unchanged.

- They might trade that US$100 on the foreign exchange market to a third person. This just transfers the question of what to do with that US$100 to that third person, who faces the same choices about whether to invest it in the United States or spend it on goods exported from the United States. Whichever choice that third person makes, it’ll ensure that the current account deficit and financial account surplus continue to be equal.

The travels of this $100 bill highlight a deeper truth: every dollar that’s spent overseas eventually returns to be spent in the United States, and this truth ensures that the current account deficit is equal to the financial account surplus.

Saving, Investment, and the Current Account

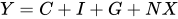

There’s another perspective on all this that’s worth considering. Recall that the total output of the U.S. economy is measured as:

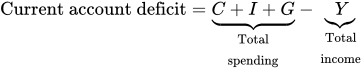

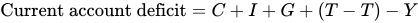

A current account deficit arises when we spend more than we earn.

In order to simplify things, let’s abstract away from investment income, so that the current account deficit is determined purely by net exports. We can rearrange the expression above to make the current account deficit the focus (remembering that the

This says that the United States has a current account deficit because total spending exceeds total income. Just as with your own finances, if you’re spending more than you’re earning, then you’ll need a cash infusion to pay for it. In the balance of payments, the excess spending is called the current account deficit, and the cash infusion is called the financial account surplus.

The current account deficit reflects the imbalance between saving and investment.

Another important perspective on the current account focuses on the role of saving. If we add and subtract tax revenues (abbreviated as T) on the right-hand side of the previous equation:

And then rearrange this expression, we get:

The first expression in parentheses is personal saving, which comes from households who save whatever income they don’t either spend or pay in taxes. The second expression in parentheses is government saving, which is the tax revenues less government spending. (When it runs a budget deficit, government saving is negative.) All told, this says that the current account deficit arises because investment exceeds total national saving (which is the sum of private and government saving, and we denote as S).

When you observe the current account deficit (or alternatively, the trade deficit), you might be tempted to focus on the tradeable sector of the economy to see if there’s a problem. This alternative perspective suggests that it’s worth focusing on what’s driving saving and investment decisions, instead.

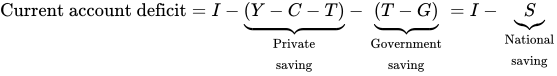

Investment is funded by a combination of domestic saving and savings from abroad.

Another way to see the link between domestic investment and saving decisions and the balance of payments is to focus on the financial account balance. Recall that a country’s current account deficit must be equal to its financial account surplus

All investment spending needs to be funded somehow. The right-hand side of this equation illustrates that investment must be funded either out of national savings, or from the savings of foreigners. By this view, financial inflows from abroad are useful because they help fund investment.

Current Account Controversies

The current account deficit—and its mirror-image twin, the financial account surplus—are both politically polarizing and poorly understood. And so it’s worth asking: Should the United States be worried about its current account deficit?

A current account deficit can reflect people living beyond their means.

Some people bemoan the “international imbalances” that lead to current account deficits. They note that as Americans spend more than they earn, they fund the gap by selling assets and borrowing from overseas. As a result foreigners are increasingly taking ownership of American factories and equipment, and Americans are going into debt to foreigners. This might be a signal of a country living beyond its means, especially if the spending is wasteful, and if people borrowing money have no idea how they’ll ever pay it back. Even the possibility that the borrowing is unsustainable can cause trouble, as it might lead to a sudden stop in which foreign investors lose confidence that they’ll be repaid and suddenly stop making loans. While sudden stops are more common in developing countries, the consequences can be severe, as a rapid decline in financial inflows requires difficult adjustments that in many cases lead the economy to tank.

A current account deficit can reflect valuable investments in the future.

Others argue that America’s current account deficit might best be thought of as a sign of economic health. The flipside of America’s current account deficit is a financial account surplus, and this inflow of funding from foreign investors has increased the supply of loanable funds, and spurred more investment. In an economy that’s ripe with opportunity, spending more than your current income can be a really good idea, particularly if that spending is directed to high-quality investments that will boost your future income. Under these conditions, reducing the current account deficit (and hence the financial account surplus) would do more harm than good, preventing businesses from making valuable investments that could be the foundation of future economic growth.

And so we’re left with the difficult conclusion that a current account deficit might be a symptom of future economic trouble, or it might be a signal of future economic strength. It really depends on how sound the millions of decisions that make up that deficit are.

Don’t worry about bilateral trade balances.

One thing nearly all economists agree on is that you shouldn’t worry about bilateral trade balances—how much we buy from one specific country compared to how much they buy from us. For instance, Americans import more from China than they export to China, and so America has a bilateral trade deficit with China. But from a macroeconomic perspective, this is largely irrelevant. What matters is whether the totality of America’s international transactions are sustainable, not just the part related to China.

The question you should ask when you’re trading is whether you’re getting a good deal, not whether the other side is buying as much from you as you are from them. As one economist memorably put it, “I have a chronic deficit with my barber, who doesn’t buy a darned thing from me.”