32.1 The Fed Model

What happens when we put the pieces together?

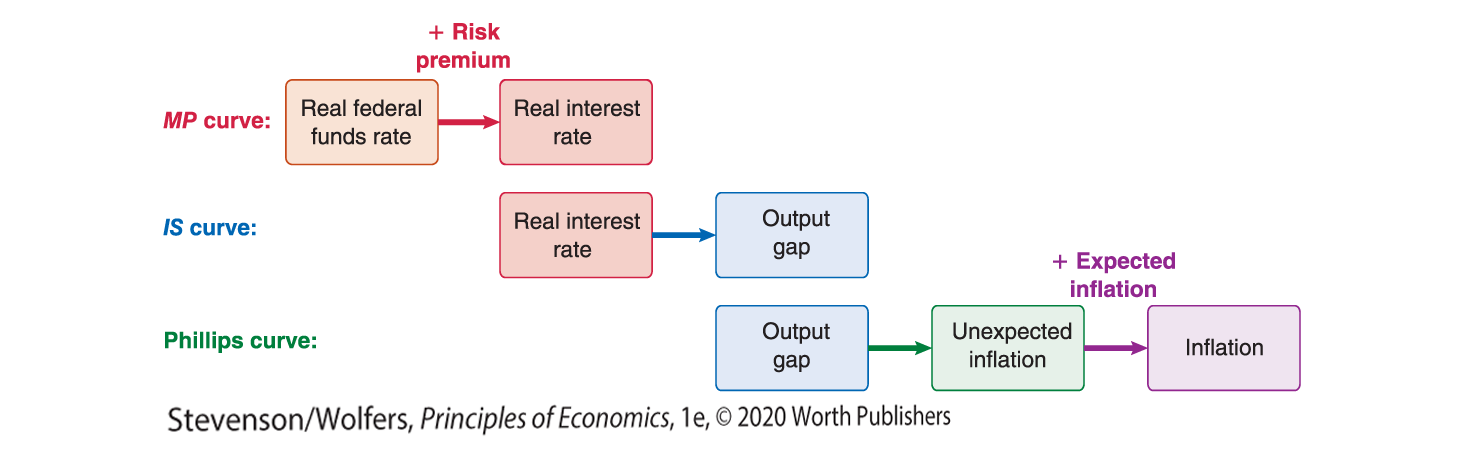

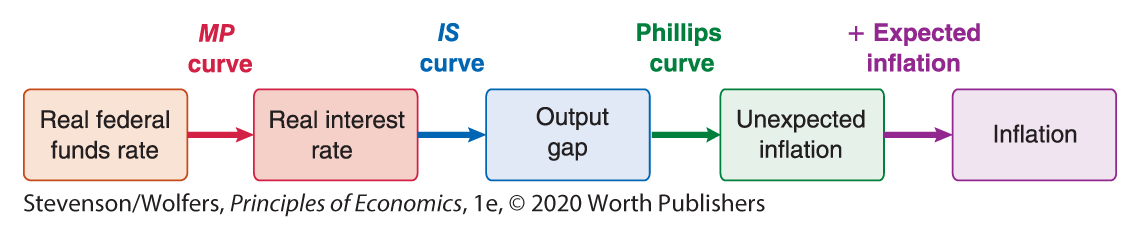

Over the past two chapters you’ve done something pretty extraordinary: You’ve developed all of the components necessary to construct a complete model of business cycles. You can draw links from monetary policy and financial markets to interest rates using the MP curve, then from the real interest rate through spending decisions to output using the IS curve, and then from the consequences for the output gap through to the resulting inflationary pressure using the Phillips curve.

In this chapter, we’ll put these components together. The result isn’t just a textbook tool, it’s the actual framework that businesses, economists, and policy makers use to understand the ups and downs of the business cycle. We call it the Fed model, because it’s the framework that policy makers at the Federal Reserve use to analyze, forecast, and tweak the economy. They use it because it represents the state of the art for understanding our economy.

The Fed Model Combines the IS, MP, and Phillips Curves

All that remains is to put each of the pieces of our analysis together into this whole. In Chapter 30, we analyzed how the intersection of the IS and MP curves determines the output gap. And in Chapter 31, we saw how the Phillips curve illustrates the role the output gap plays in shaping inflation. Put the pieces from these two chapters together, and you’ll be able to forecast interest rates, the output gap, and inflation.

You can see the connections as follows:

The Fed model isn’t a distinct mode of analysis. Rather, it puts together the pieces you’ve already developed. That’s why it’s sometimes also called IS-MP-PC analysis, because it combines IS-MP analysis with the Phillips curve (or “PC” to its friends):

Forecasting Economic Outcomes

Putting these pieces together requires stepping through each of the basic tools we’ve developed in the past two chapters, in turn.

Start by finding the output gap.

Begin your analysis with the IS-MP framework, which determines the output gap. We do this in the top panel of Figure 1, which reproduces a familiar chart from Chapter 30. Remember that the vertical axis is the real interest rate and the horizontal axis is the output gap. The MP curve is a horizontal line illustrating the current real interest rate, and the IS curve is a downward-sloping line illustrating how a lower real interest rate stimulates more spending and output.

Figure 1 | The Fed Model

Importantly, macroeconomic equilibrium occurs where the MP curve cuts the IS curve. You can look down from the point where the curves cross to find the resulting output gap. In the example shown in Figure 1, you would forecast an output gap of −5%.

Next, assess inflation.

Use the Phillips curve to figure out the inflationary implications of this output gap. I’ve stacked the Phillips curve directly under the IS-MP curves in Figure 1, so you can trace the output gap down from the top panel to the lower panel until you hit the Phillips curve. Once you’ve found the Phillips curve, you just need to look across to find out what will happen to inflation. Recall the vertical axis of the Phillips curve tells you what will happen to unexpected inflation, and you also need to consider the influence of inflation expectations. So to forecast actual inflation, you’ll add this forecast of unexpected inflation to the latest reading of inflation expectations.

In this example, an output gap of −5% leads to unexpected inflation of −1%, which means that actual inflation will be 1% below expected inflation. If inflation expectations are 2%, this says inflation will be 1%.

You can see why Fed economists like this style of analysis—it delivers a complete set of forecasts: the real interest rate will be 4%, the output gap will be −5%, and unexpected inflation will be −1%, and so if expected inflation is 2%, inflation will be 1%.

But what will happen if economic conditions change? That’s where the Fed model really shines. So let’s read on.

Three Types of Macroeconomic Shocks

Warning: Potential shocks ahead.

There are dozens of shocks that might hit the economy. You can just imagine the headlines: Stocks crater! Productivity surges! Banks fail! Confidence soars! Exports wither! Dollar skyrockets! Fed cuts rates! Uncertainty rocks markets! Oil prices plummet! Wages boom! And so on … (So! Many! Exclamation points!)

There are financial shocks, spending shocks, and supply shocks.

Fortunately, the Fed model categorizes each of these many possibilities into one of three types of shocks, each of which is familiar from the past two chapters.

- Financial shocks: Any change in borrowing conditions that affects the real interest rate—whether due to the Federal Reserve shifting the federal funds rate, or changes in financial markets shifting the risk premium—will shift the MP curve.

Spending shocks: Any change in aggregate expenditure at a given real interest rate and level of income—whether due to consumption, planned investment, government expenditure, or net exports—will shift the IS curve.

Supply shocks: Any change in production costs that leads suppliers to change the prices they charge at any given level of output will shift the Phillips curve. Common supply shocks include changes in input prices, productivity, and the exchange rate.

The Fed model brings together three curves, which are shifted by the three kinds of shocks. Thus, we can summarize our complete framework—which includes the IS, MP, and Phillips curves, as well as the economic shocks that cause them to shift—as follows:

This taxonomy is tremendously helpful because it means that forecasting the consequences of whichever of the zillion things that might happen next to the economy—a collapse in the banking system, plummeting consumer confidence or rising oil prices—doesn’t require a zillion different kinds of analysis. Rather, you simply need to figure out if you’re dealing with a financial shock (such as when the banking system collapses), a spending shock (such as when plummeting consumer confidence leads to a decrease in consumption), or a supply shock (such as when oil prices skyrocket). Then it’s simply a matter of exploring how that type of shock will affect the economy.