34.3 How the Fed Sets Interest Rates

When the FOMC announces that it will raise or lower interest rates, it’s announcing a new level for a specific interest rate called the federal funds rate. But it doesn’t directly set the federal funds rate, which you’ll recall is the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans in the federal funds market. Only banks and certain other financial entities can borrow and lend in this market. So in order to implement its new monetary policy decision to shift this interest rate, the FOMC needs to create incentives for banks that shift the supply or demand for loans in this market. Let’s explore how it does this.

The Overnight Market for Interbank Loans

We’ll begin by thinking through why banks sometimes need to borrow from each other overnight. When you deposit your paycheck in a checking account, the money doesn’t just sit as cash in the vault. Banks make money by lending out the funds you’ve deposited. But when you write a check to your landlord to pay your rent, you expect the bank to give that money to your landlord. Banks must keep cash on hand—known as reserves—so that they can make those payments. So banks face a trade-off: If they loan more of their money out, they make more revenue from borrowers paying them interest on those loans, but they also risk not having enough cash available to make payments like the one to your landlord. When they don’t have enough cash on hand, they’ll need to borrow money to make those payments.

The Fed sets reserve requirements: a minimum amount of reserves—that is, available cash—that each bank must hold. They have to either hold these reserves as cash in their vaults, or on deposit at the Fed. Sometimes banks don’t have enough ready cash to meet the reserve requirement or are short of what they need to make payments on a given day. As a result, they have a demand for funds, which they can meet by borrowing money overnight from another bank in the federal funds market. Other banks may have more cash than they need. These banks are willing to supply funds, lending their spare cash overnight to those who need it. The forces of supply and demand determine the price in this market, which is the interest rate charged on these overnight loans. It’s called the federal funds rate because it is the price in the market for funds to meet the Fed’s reserve requirements.

The Fed can try to influence the federal funds rate by changing the reserve requirement. If the Fed raises the reserve requirement, the supply of funds available in the federal funds market will decrease as banks are required to keep more funds in reserve and thus have less available for lending. This decrease in the supply of funds will raise the federal funds rate. In reality, the Fed doesn’t change the reserve requirement very often.

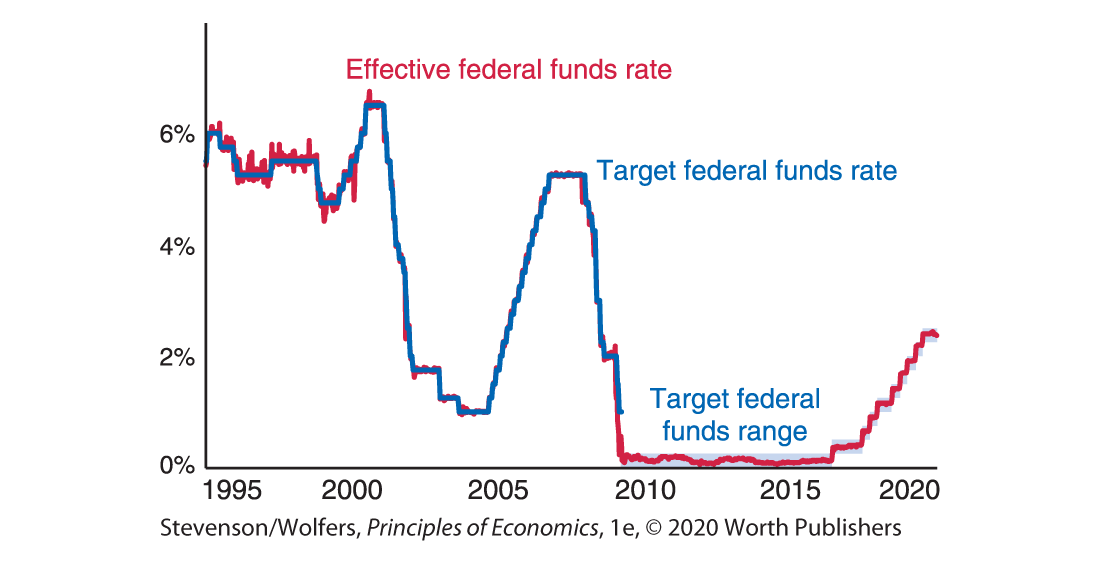

But this intuition can help you understand the tools the Fed does use, many of which are designed to encourage banks to hold more or less in reserves. These tools effectively shift the supply or demand of overnight loans to achieve the goal of changing the equilibrium interest rate in the federal funds market. These tools work well: Figure 4 shows that the actual interest rate—called the effective federal funds rate—is usually incredibly close to the Fed’s target for the federal funds rate. (Notice that the Fed used to set a specific target for the interest rate, but since late 2008, it has set a target range.) Let’s explore the tools the Fed uses to hit these interest rate targets.

Figure 4 | The Federal Funds Rate

Data from: Federal Reserve.

Tool one: The Fed pays interest to banks on their excess reserves.

In order to influence the federal funds rate, the Fed pays interest to banks on excess reserve balances—the reserves they hold above the amount required. This effectively creates a minimum interest rate that a bank will charge before loaning its excess funds to other banks. (The Fed also pays interest on required reserves, but since those reserves are required, that interest doesn’t affect banks’ willingness to lend their extra cash.)

If you can just leave your extra cash in your own reserve account and earn a 1% return with no risk of losing your money, you’ll only take it out of your account and lend it to someone else if they offer a rate higher than 1%. As a result, the interest rate on excess reserves effectively serves as a floor on the interest rate at which banks will loan their funds. The higher this interest rate, the fewer reserves are available to loan to other banks, which will raise the interest rate on overnight loans. And so when the Fed wants to increase or decrease the federal funds rate, it raises or lowers the interest rate it pays on excess reserves.

However, not all institutions in the federal funds market are eligible to receive interest payments on their reserves. So the Fed must use another tool to set an effective floor for the federal funds rate at those institutions. Let’s turn to that tool now.

Tool two: The Fed borrows money overnight from financial institutions.

The Fed has another way of establishing a floor for the price of borrowing money: It can borrow from financial institutions and pay them interest on the loan. By engaging in overnight borrowing, the Fed increases the demand for overnight loans, which leads to higher interest rates. When it reduces such borrowing, it decreases the demand for overnight loans, which lowers rates. It does this primarily to have a tool to set an effective floor for the federal funds rate at financial institutions that aren’t banks.

Let’s see how this tool works. The Open Market Trading Desk, informally known as the Desk, is a trading desk at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; traders at the Desk buy and sell government bonds. Government bonds are IOUs from the government, saying that the government promises to pay back a certain amount by a certain date at a particular rate of interest. The Fed isn’t borrowing money itself, it’s simply trading government bonds just like you might buy or sell government bonds (if you have a retirement account, you’ve probably bought government bonds, albeit indirectly). The difference is that the Fed is trading these bonds in order to influence interest rates. The Desk engages in these trades in order to carry out the directions of the FOMC to influence the federal funds rate. The Desk is called the “open market” desk because it’s required to buy and sell in the competitive open market.

The Desk is housed at the New York Federal Reserve Bank.

The Desk sells a government bond to a bank or other financial institution overnight, with an agreement to buy it back the next day at a higher price. These sales are called overnight reverse repurchase agreements. This might sound complicated, but the idea is actually pretty simple: If I sell you a piece of paper today and agree to buy it back at a higher price tomorrow, you’re giving me your cash today and I’m promising to give you more cash tomorrow. Effectively then, I’m borrowing your money overnight, and the difference between the cash you give me today and the cash I’ll pay you tomorrow is the interest I’m paying you. That’s what these agreements do—they set an interest rate at which the Fed is willing to borrow money. These loans effectively set a floor for the federal funds rate—because why would a financial institution lend its money to someone else if it could lend to the Fed and make more in interest?

Both paying interest on excess reserves and the rate of return on overnight reverse repurchase agreements put a lower bound on the federal funds rate. Together, this method of implementing Fed policy for the federal funds rate is known as the floor framework because it effectively sets a floor on how low of an interest rate a financial institution will be willing to lend to another.

Essentially, the Fed raises the opportunity cost of lending in the federal funds market. Since no bank should want to lend at a rate lower than its opportunity cost, the alternative options the Fed provides for banks and other financial institutions to earn interest puts a lower bound on how low the federal funds rate will go.

Tool three: The Fed lends to banks directly through the discount window.

There’s another way the Fed can influence the amount of reserves that banks hold, but the reality is that it isn’t used that much. It can lend directly to banks through the discount window. It’s called that because in the old days, there was an actual window at each of the district reserve banks, where banks sold their loans to the Fed at a discount and later bought them back. Essentially, it was a pawn shop for banks. It doesn’t work quite the same way anymore, but the name has stuck. And the main idea is the same—banks offer collateral (something they’ll lose if they don’t pay back the loan) and get a loan from the Fed that helps them meet their reserve requirements.

The interest rate that the Fed offers through the discount window is called the discount rate, and it’s typically set higher than the federal funds rate. It’s important because it creates an upper bound for the federal funds rate. Banks prefer to borrow from each other at the federal funds rate, but if the federal funds rate goes above the discount rate, they can just borrow from the Fed at the discount rate.

So the Fed can affect the federal funds rate by operating as an alternative lender. When the Fed wants to increase or decrease the federal funds rate, it raises or lowers the discount rate accordingly.

Tool four: The Fed buys and sells government bonds.

The last tool is really more of a history lesson. Prior to 2007, rather than trying to influence the federal funds rate by setting an interest rate floor and ceiling, the Fed would buy and sell bonds until they achieved their desired interest rate in the federal funds market. If the Fed wanted to raise rates, it would tell the Desk at the New York Federal Reserve Bank that it should sell bonds. When a bank buys a bond from the Fed, the money it pays is taken from its reserves. With fewer reserves, the bank is more likely to need to borrow reserves and less likely to be able to supply them to other banks. By selling bonds, the Fed increases demand for overnight loans and decreases supply. The net result is that the Fed’s bond sales push the federal funds rate up.

When the Fed wanted to lower rates, it bought bonds. The money the Fed paid for the bond added to banks’ available reserves. Because banks had more reserves, they’d be less likely to need to borrow from another bank overnight and more likely to be able to lend. By purchasing bonds, the Fed decreases the demand for overnight loans and increases the supply. Therefore, the Fed’s bond purchases push the federal funds rate down.

Open market operations refers to the Fed buying and selling government bonds. Technically, overnight reverse repurchase agreements are a form of open market operations. But historically open market operations through buying and selling bonds were the primary way that the Fed implemented monetary policy decisions.

In the 2000s, Fed officials began looking for alternative approaches to move interest rates because buying and selling bonds through standard open market operations didn’t always achieve their desired federal funds rate. The financial crisis sped up some of those changes. Today the Fed uses a floor framework plus the use of an effective price ceiling through the discount rate. By setting the relevant prices—that is, a floor and ceiling for interest rates—and letting market quantities adjust, the Fed can precisely target the federal funds rate without having to indirectly try to influence this price by changing the quantity of bonds traded in the market.

The Impact of Changing the Federal Funds Rate on the Rest of the Economy

The Fed’s decisions ripple out and affect every part of the economy.

Ok, so now you know how the Fed adjusts its main tool—the federal funds rate. But how does that affect you? Once the Fed has succeeded in moving the federal funds rate, the effects ripple throughout the economy. Banks adjust many of their interest rates such as those on credit cards, business loans, mortgages, student loans, savings accounts, and auto loans. Those interest rate changes then have broader macroeconomic effects. A lower real interest rate leads to more consumption and investment, an exchange rate depreciation, and higher net exports. This rise in aggregate expenditure leads managers to expand production, which requires them to hire more workers. Higher output leads more businesses to experience capacity constraints, leading them to raise their prices more frequently and by larger amounts, boosting higher inflation. People follow the Fed’s decisions closely because they eventually affect nearly every corner of the economy, both in the United States and abroad. Let’s see how all of this happens.

A change in the federal funds rate percolates through to other interest rates.

When the federal funds rate changes, banks reset the rate they charge borrowers because the marginal costs and benefits of making loans has changed. The marginal benefit to your bank of loaning money to you is the interest you pay. Its marginal cost is the opportunity cost—the interest it could earn by leaving the money in its reserves, instead. When a lower federal funds rate leads this opportunity cost to fall, the cost-benefit principle tells banks to make more loans at any given interest rate. This increase in the supply of loans causes the interest rate that banks charge folks like you to fall.

The federal funds rate directly impacts short-term and variable interest rates. Many variable interest rates—such as the rates on most credit cards—move directly with the federal funds rate. Some private student loans also have a variable rate. Your savings account may have a variable rate that adjusts with the federal funds rate.

Changes in short-term interest rates also percolate through to longer-term loans. To understand why, realize that a longer-term loan can be thought of as a series of short-term loans. So when you pay a fixed interest rate on a five-year car loan, the bank can think of adding up the different interest rates it would charge over each month of the five years. Since the opportunity cost for the bank of making you a five-year loan is not making a series of short-term loans, it will only do so if the interest it earns is at least as great as what it could expect to earn on a series of short-term loans. As a result, long-term interest rates move when the federal funds rate changes, and how much they move depends on how long banks expect the federal funds rate to be at its new rate.

Interest rates change the value of consuming today versus consuming tomorrow.

For consumers and businesses, consumption and investment change with the interest rate because of the opportunity cost principle. When the Fed changes the federal funds rate, the effects filter through to change the interest rates you face on things like your savings account and credit cards, which affects your choices about how much to save or borrow. Similarly, the return on savings for businesses changes, as does the cost of borrowing. Likewise interest rates change how much the government pays to borrow, therefore potentially affecting how much the government has available to spend on other things.

Interest rates change the value of the U.S. dollar.

Fed decisions affect the U.S. dollar, which affects Japan and the rest of the world.

Investors are global actors, seeking the highest risk-adjusted returns they can find. When U.S. interest rates fall, investing in the United States becomes less attractive. With fewer foreign investors trying to buy U.S. dollars so that they can invest in America, the value of the dollar falls. This depreciation means that it takes fewer yen, euros, or yuan (the currencies of Japan, Europe, and China) to buy an American dollar.

When it takes fewer yen to buy a dollar, Japanese consumers can buy American-made goods more cheaply. If you’re exporting apples to Japan, you’ll get the same number of dollars, but it costs your Japanese customers fewer yen. And that increases demand for your exported apples. Indeed, when the dollar depreciates, people around the world will discover that American goods will be cheaper in terms of their own currency, leading them to buy more goods exported from the United States.

The flip side is that it takes more dollars to buy goods priced in other currencies. In order for a Japanese auto manufacturer to receive the same number of yen, you must pay more U.S. dollars for a Japanese car. That price rise leads to a decline in the quantity of imported goods that Americans demand. If the quantity of imports declines by enough to offset the higher prices, then total spending by Americans on imported goods will also fall.

All this means that low interest rates lead to a cheaper U.S. dollar, causing exports to rise and imports to fall, thereby increasing net exports. The opposite happens when interest rates rise: The value of the dollar rises, making U.S. goods more expensive and foreign goods cheaper, and this leads to a decrease in net exports.

The Fed’s decisions, therefore, percolate through the entire global economy because of their impact on global financial flows, exchange rates, and international trade. To summarize, a change in the federal funds rate changes real interest rates throughout the economy, which in turn changes consumption, investment, government spending, and net exports.

EVERYDAY Economics

The Fed just lowered interest rates. Does that mean it’s a good time to borrow?

The Fed just lowered rates. Should you take out a car loan?

When the Fed lowers the federal funds rate, other interest rates will follow. You’ll likely be able to take out an auto loan for less as a result. So does this make it a good time to buy a car? The Fed hopes you think so—after all, it’s trying to boost spending with the lower rates. But whether this is a good decision depends on your personal situation. In particular, it’s important to realize that the Fed lowers rates when it sees the economy weakening. That means that you should factor in the chance that you might lose your job. If that were to happen, would you still be able to make payments? Typically, young people are the most vulnerable to high rates of unemployment during an economic downturn. So be extra careful with your budget when you see the Fed lowering rates, and perhaps hold off on that car purchase until you’re sure you could support yourself (and the car payment) if you lose your job.