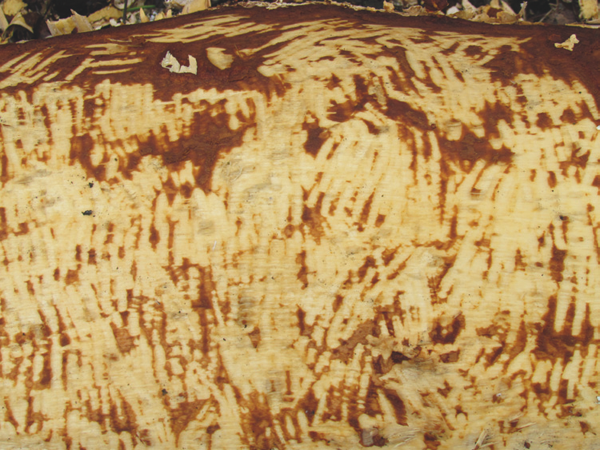

Figure A.1 Distinctive teeth marks left by beavers when felling trunks/removing branches. (R. Campbell-Palmer)

The teeth pattern left in beaver-felled wood is highly distinctive (Figures A.1 and A.2). When felling tree trunks or removing side branches, the patterns produced are those in Figure A.1 – a cutting action with no consumption – while the teeth marks in Figure A.2 represent bark-stripping, in which bark is consumed.

Figure A.1 Distinctive teeth marks left by beavers when felling trunks/removing branches. (R. Campbell-Palmer)

Figure A.2 Distinctive teeth marks left by beavers when stripping bark for consumption. (R. Campbell-Palmer)

On saplings and smaller side branches, the angle of the cut results in a ‘whistle’-shaped profile, while on larger tree trunks the beavers’ gnawing and felling can result in very distinctive ‘pencil-sharpened’ points. Marks left by their incisors can be clearly seen or felt by running a finger across the cut end. Beavers fell timber by cutting chips from the main stem with the upper and lower incisors, alternating from one side of the head to the other, creating a distinctive scalloped pattern in the trunk. When beavers gnaw through substantial timber, they produce distinctive chippings (Figure A.3).

Figure A.3 Freshly felled tree with distinctive chippings. (Scottish Beaver Trial)

Gnawed wood, peeled sticks and wood chippings can all be classed as fresh or old by their colourations, which are very pale when fresh and darken with age (Figures A.4 and A.5).

A.3 Ring-barking/bark stripping

Ring-barking can typically be seen on conifers and non-typical food-tree species such as beech (Fagus sylvatica). This is when sections of bark are pulled of the trunk by the beaver, usually in an upward motion, in thin strips. If this results in a full ring barking of a tree, it is probably created as the animals walks around the trunk removing bark at the most accessible level, rather than an actual attempt to fell a tree. Ring-barking is generally unpopular, especially on large trees in public areas.

Figure A.4 Old ring-barking by beavers. (R. Campbell-Palmer)

Figure A.5 Fresh ring-barking by beavers. (Gerhard Schwab)

A.4 Grazed lawns and cut vascular plants

Beavers feed on a wide variety of vascular plant species and woody shrubs. On more rigid cut stems, a typical 45° angle cut is visible. Feeding by beavers on root or cereal crops is distinctive. They will completely clear a discrete area of up to several square metres where the crop is adjacent to a watercourse. The site will have obvious worn access trails and, for some crop types such as maize, distinctive 45° angle feeding cuts. Root crops can be completely extracted in small patches and removed for storage in nearby burrow systems. Beavers can also produce tightly mown grazing lawns. These are created by regular feeding on vascular plants within the same area and can extend over several square metres, with a definable perimeter surrounded by longer sward. These lawns can be distinguished from the more general grazing patterns of larger water fowl such as geese by an absence of feathers and guano, and worn forage trails, leading from the water’s edge, are usually nearby.

Figure A.6 Beaver-cut bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) stems (Knapdale, Scotland). (R. Needham)

Figure A.7 Beaver feeding on roots of vascular plants (River Earn, Scotland). (R. Campbell-Palmer)

Beavers often repeatedly feed at the same location on the water’s edge for extended periods. Many freshly peeled sticks float away on the surface of the water into the wider environment or lie submerged in and around the feeding sites. In habitats that are densely vegetated, identification of these pale twigs in the water or on land along the shoreline can often be the first indication of the presence of beavers. These feeding stations can vary greatly in size from just a few sticks to well over 100 in number. Their approximate age can be established by the coloration of the peeled sticks (lighter tends to equal fresher) (Figure A.8(a)) and/or the presence of freshly cut green vegetation (Figure A.8(b)).

Figure A.8 Feeding station, with freshness of activity defined by (a) presence of freshly peeled sticks and, potentially, by (b) freshly cut green vegetation (depending on season). (Scottish Beaver Trial)

Beavers often forage repeatedly at points not on the immediate shoreline. Regular movements to and from these create trails and pathways (Figure A.9).

Figure A.9 Typical beaver haul-out point along a shore, and foraging trails. (D. Gow and R. Campbell-Palmer)

These features are further worn by repeated dragging of branches back to the water. Following these trails inland may lead to further field signs such as cut branches and felled or gnawed trees. These routes are usually easily visible along the shoreline, especially if snowfalls occur. They make excellent locations for positioning camera traps. Foraging trails often lead from feeding stations, which are often situated in the water or near to the shore.

Beaver lodges and burrows are the focal points of a beaver family, providing shelter from the elements and from predators. They vary greatly in shape and size depending on the surrounding habitat and number of occupants. Some dwellings can be very obvious structures at the water’s edge, or occasionally free-standing in ponds, while others consist of burrows or chambers with few or no obvious external features. Burrows will frequently be excavated under the root plates of large trees, although burrow structures do vary greatly. Some burrows have tunnels running from the living chamber into the surrounding landscape. These are commonly used for foraging purposes. Although most are less than 5 m in length, some can extend for greater distances. Mud, branches and other vegetation are the usual construction materials for lodges. These structures can contain a number of chambers. Beavers always enter and leave these structures via a submerged entrance, often obscured by a protruding structure of woody debris. Lodges can survive as features for some time after they are no longer occupied by beavers. If beavers are in residence, fresh feeding signs or foraging trails are usually evident in the immediate vicinity of a lodge. If the branches on a lodge are carrying green leaves that have not yet wilted, this is a good indicator of current occupancy, as is wet mud or the presence of aquatic plants on the outer surface. Fresh building and food-caching activity mostly takes place, and is therefore most obvious, in the autumn.

Figure A.10 Free-standing beaver lodge (left). (R. Campbell-Palmer)

Figure A.11 Drained beaver pond with exposed lodge with multiple entrance and exit tunnels visible (these would usually be submerged). (G. Schwab)

Figure A.12 An active lodge (no food cache as yet present, cache construction occurred later) with fresh mud layer, debarked branches and branches with fresh vegetation. (H. Parker)

Figure A.13 An inactive lodge, dry in appearance, with old branches and no evidence of fresh mud or cut vegetation. (H. Parker)

To create a lodge, beavers usually first dig a burrow or excavate a cleft in banking next to the water. In rocky environments or artificially reinforced river banks, beavers may adapt any available shallow shelves. Once a construction point is selected, it is built upon or added to by piling layers of sticks, mud and vegetation on top. Where branches protrude into the walls of the chamber, they are smoothed of through gnawing. The internal floor is lined with a bed of finely split wood shreds. Living chambers are formed in two ways. If the bankside substrates are suitable, then the beavers will excavate tunnels and chambers by digging. Where the substrates are not so suitable for digging, more of a lodge structure is built outwards from the bank itself. Burrows frequently break the surface sometime after first occupation. When they do, a ‘roof’ is constructed of sticks and mud; this may develop into a bank-lodge, a structure starting from the water as a burrow and ending as a lodge standing on the bank a short distance from the water.

There are, therefore, three principal lodge designs: a free-standing structure in a pool (known in North America as a ‘brook lodge’), a bankside lodge and a burrow lodge. The first type is established when beavers dam a small stream to create a pool which subsequently expands to surround the lodge. The lodge is then built up in response to the deepening water. The second type is a structure entirely constructed from sticks, mud, etc., including the underwater entrance. The third is the burrow lodge described above.

It is important to be able to determine if a lodge is occupied or not, and this is best judged visually in the autumn when beavers prepare for the winter period. Those lodges that will be used that winter will almost always have fresh additions of debarked branches, mud and often some kind of green fresh vegetation, along with a food cache (which may be partly visible). Alternatively, an abandoned lodge will lack these features, and look ‘dry’ in appearance.

Burrows may extend from the shoreline and open above ground nearby, acting as access routes from the water’s edge to food sources further up the bank. Most burrows are not visible above ground, although their entrances can sometimes be observed where the water is clear or where levels are unusually low. In narrow watercourses, these burrows are most likely to be found by viewing from the opposite bank, or from a canoe in wider or deeper watercourses. The growth of tall vegetation in the summer months can easily obscure even large beaver lodges. Beavers can also create ‘day rests’ (lairs), which are scrapes or shallow burrows lined with shredded woody vegetation, situated close to the water’s edge, where they may sleep in preference to the main lodge during the warmer summer months. Radio-assisted observations in 11 well-established beaver territories in Telemark county, Norway, found that the beaver groups each regularly use an average of seven lodges and burrows (range: six to eight) at any given time (Rosell and Campbell, unpublished).

Figure A.14 Beaver-shredded bedding. (D. Gow)

Figure A.15 A ‘day rest’ under a tree with shredded bedding visible. (J. Coats)

Beavers often collect large quantities of woody browse during the autumn months to create winter food stores. This practice varies with climate, being more common in climates with greater risks and longer durations of winter ice cover. Cut branches are secured by jamming them into the substrate, usually at a point just outside the lodge entrance. Other branches may then be woven through or piled upon. When they are not completely utilised by the beavers or dislocated by river flows, some branches, particularly willow, can begin to regrow in the spring of the following year.

Figure A.16 Beaver lodges with food caches: mid-winter. (Scottish Beaver Trial)

Figure A.17 Beaver lodges with food caches: pre-winter, with leaves still visible on cut branches. (Scottish Beaver Trial)

Beaver dams vary considerably in height, extent and character. They can initially be formed around natural features such as fallen trees or large rocks, or where channels narrow. Dams are constructed from various materials including sticks, branches, mud, stones and vegetation. Beaver dams are faced on their upstream side by ramps of mud shovelled by the beavers and sediment trapped by the dam itself (Wilsson 1971). In some watercourses, dams are only tenable in the summer months and are destroyed by the winter flows. It should be noted that the creation of dams by beavers depends on stream characteristics. Dams are usually only built where the watercourse is initially less than 0.8 m deep and less than 6 m wide (Hartman and Törnlöv 2006), and with stream inclines of less than 2%. Dam systems can exist as multiple impoundments or as individual structures. When newly created from timber, they are unvegetated. As they age, they are rapidly overgrown and, if not kept in repair by the beavers, will gradually decline in height as their organic components decay. As the area behind a beaver dam becomes less water logged, a series of plants recolonise the area and ‘beaver meadows’ are formed, with associated plant succession as the area dries out.

Figure A.18 Abandoned beaver territory with unmaintained dam (lodge visible in the background on the left). A drop in water level has resulted in increased emergent vegetation and the start of beaver meadow formations. (H. Parker)

Although well-worn foraging trails may eventually fill with water, beavers will also actively excavate networks of small canals (Figure A.19) in flatter habitats. These structures, which branch out from a principal water body, will be cleared by the beavers of sediment, detritus, fallen leaves or other vegetation on a regular basis. This excavated debris is placed on the canal side in irregular mounds. Beavers use these canals to transport browse and building materials; they also provide escape routes back to deeper water and safety. Where conditions allow, numerous canals can be created. Most are of short length, but some can extend 150 m or more from the main water body. The average width is 40–50 cm. Canals may contain a series of small dams or muddy impoundments which can be reinforced during droughts to allow them to retain water.

Figure A.19 Beaver-dug canals in Norway. (D. Halley)

Scent mounds are small piles of mud, vegetation or other detritus that beavers gather from the surrounding environment. These are deposited on the bankside or on a rock or islet in a water body, and are marked using castoreum and/or anal-gland secretion. Scent mounds can be hard to find unless searched for carefully; but, if recently marked, the camphor-like smell is quite distinctive.

Figure A.20 Beaver scent mounds can sometimes be difficult to spot, but the camphor-like smell will be a giveaway. (R. Campbell)

Normally, urination and defecation occur in the water (Wilsson 1971), and therefore beaver faeces are not often seen. The fibrous nature of the faecal content ensures that breakdown is relatively swift, especially in habitats with flowing water. Pellets of faeces ~5 cm long may occasionally be seen in the vicinity of lodges or feeding stations in areas of still or slow-moving water.

Complete beaver tracks can be hard to find, as a heavy, wet animal which drags its tail behind it can produce distorted tracks. These are further obscured when beavers drag branches behind them. Intact prints of the fore and hind paws differ greatly. The hind paws are large and long. A clear print will display the outline of the web of skin connecting the toes. It is unlikely that this could be mistaken for other native riparian mammal in Britain. The smaller forepaw print is also distinctive, although the outline of every toe is not always clear. Where beaver trails are well used, individual tracks become less distinct. Muddy or snowy trails, banks with sparse vegetation and areas around their lodges, dams or canals are all good places to search for tracks.

Figure A.21 Beaver faeces trapped behind a beaver dam. It is unusual to observe beaver faeces, as defecation occurs in the water and hence faeces often break apart, though they may be recovered in shallow, still water. (D. Gow)

Figure A.22 Beaver tracks: forepaw and hindpaw. (Rachael Campbell-Palmer)

Figure A.23 Beaver tracks to scale. (Left) Forepaw top right. (Right) Hind (webbed) paw lower track. (R. Campbell-Palmer)