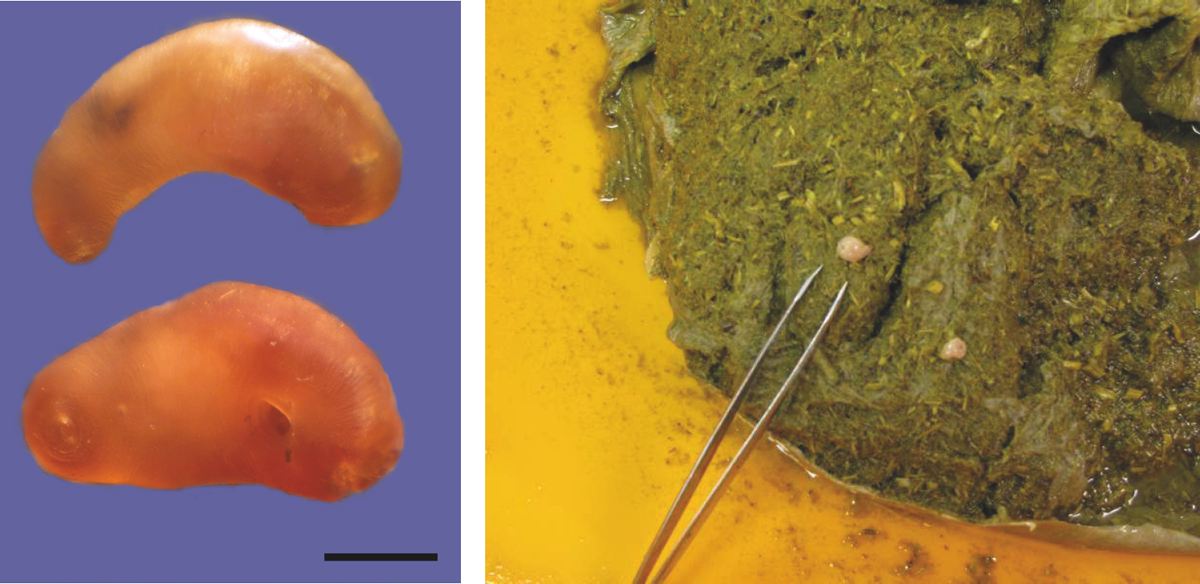

Figure B.1 The beaver beetle (Platypsyllus castoris), a host-specific ectoparasite of beavers. (S. Gschmeissner, R. Zange.)

Diseases and parasites of the Eurasian beaver

Any health assessment of a wild or captive beaver should be carried out with specialist veterinary support and refer to current published baseline parameters for the Eurasian beaver (Goodman et al. 2012; Cross et al. 2012; Girling et al. 2015). Like all other rodents, beavers may harbour common European rodent pathogens (Goodman et al. 2012). It is recommended that any imported, wild-caught beavers are screened for the following as a minimum: Echinococcus multilocularis, hantavirus, tularaemia, Yersinia spp., leptospirosis, Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp. and Toxoplasma gondii – and quarantined for rabies as appropriate.

Beavers can host specific parasites which are of no harm to other species. These include the beaver beetle (Platypsyllus castoris), a small, wingless insect that lives on their skin and fur (Peck 2006). Although these beetles may be mistaken for fleas, they do not jump and are a rusty orange/brown in coloration (Figure B1). Both the larvae and adult beetles feed on the epidermal tissue of the beaver’s skin without any visible signs of irritation (Wood 1965). Beetles have been recorded on Scottish-born beavers (Duff et al. 2013). There is only a single record of a host-switch to an otter (Belfiore 2006), which possibly occurred when the otter was present inside a beaver lodge (Peck 2006). The pupal stage of the beetle is found in the earth of beaver lodges or burrows (Peck 2006). Due to desiccation or extremes in temperature, adult beetles do not survive for long when they leave their host (Janzen 1963).

More than 45 species of Schizocarpus mite are associated with the Eurasian beaver (Bochkov and Saveljev 2012). These mites are usually spread through direct contact; and, although more than 10 species may live on an individual beaver at any one time, they are often restricted to a particular area of the body (Bochkov and Saveljev 2012). Beavers may harbour ticks, but these parasites do not appear to be present in all individuals or in significant numbers and are probably largely removed by the beaver’s specially adapted grooming claw (Figure B2). As with other species, ticks can transfer haemoparasites (blood-borne parasites) and Lyme disease (bacteria Borrelia spp.) to their hosts. Although haemoparasites have not been recorded to date in Eurasian beavers (Cross et al. 2012), further investigations are encouraged.

Figure B.1 The beaver beetle (Platypsyllus castoris), a host-specific ectoparasite of beavers. (S. Gschmeissner, R. Zange.)

Figure B.1 Grooming claw found on the webbed hindfeet of the beaver, used to keep hair ‘unclumped’ to maintain effective insulation and assist in removing ectoparasites. (S. Jones)

Travassosius rufus is a stomach nematode specific to beavers and has a direct life cycle, with its eggs being expelled in beaver faeces (Åhlén 2001). These thin worms can be identified within the beaver stomach walls and stomach contents at post-mortem, or by the presence of eggs in the faeces.

Stichorchis subtriquetrus is a specialised trematode or intestinal fluke found only in beavers, mainly in their caecum and large intestine. Its life cycle incorporates an aquatic snail as the intermediate host, which infects a beaver when it ingests aquatic plants (Bush and Samuel 1981). This host-specific parasite has been found in Scottish-born beavers (Campbell-Palmer et al. 2013).

Cryptosporidium spp. is an intestinal protozoan parasite that causes disease in the small intestine, particularly in immunocompromised or naïve individuals. It is zoonotic species that causes diarrhoea, usually self-limiting, in humans. The transmission route is faeco-oral. It is a common condition of various wildlife and domestic animals already present in the UK; beavers are most usually infected by domestic cattle.

Figure B.2 Beaver intestinal fluke (Stichorchis subtriquetrus), adult fluke (left) and adult fluke in opened caecum (right); this fluke is largely found in the caecum and large intestine. (J. del Pozo and R. Campbell-Palmer)

Giardia spp. is another intestinal protozoan parasite. Although beavers have been implicated in human outbreaks – a media-inspired name being ‘beaver fever’ – it should be noted that this parasite naturally occurs in the environment and is present in wildlife, domestic livestock and human populations within the UK, which may provide a source of infection to the beaver (Morrison 2004). This parasite lives in the small intestine and can cause diarrhoea and abdominal pain in all mammals. In a survey of 241 wild-trapped Norwegian beavers, none tested positive for Giardia (Rosell et al. 2001).

Echinococcus multilocularis (also known as the fox tapeworm) is a pathogenic zoonotic parasitic present throughout Central Europe. There is currently no evidence of its existence in the wild in the UK, though the potential for unscreened, directly imported beavers to introduce this parasite has received attention (Simpson and Hartley 2011; Pizzi et al. 2012; Kosmider et al. 2013; Campbell-Palmer et al. 2014). Barlow et al. (2011) diagnosed E. multilocularis post-mortem in a captive beaver which had been wild-caught and imported from Bavaria years previously. The definitive host is usually the Red Fox, but domestic cats and dogs can also function as definitive hosts (Eckert and Deplazes 1999). Various rodents, mainly voles but rarely including beavers, function as intermediate hosts through which the tapeworm can be transmitted when they are consumed by a fox (Janovsky et al. 2002). Humans can also act as an accidental intermediate host, with the mean annual incidence rates ranging from 0.02 to 1.4 cases per 100,000 inhabitants in different parts of Europe; infected people often require life-long medical treatment (Eckert 1997). Captive collections should ensure that any beavers imported from areas where this parasite is endemic are not allowed to be scavenged by carnivores, as the parasite can only become a threat to humans if it gains access to a carnivore’s digestive tract. As beavers are intermediate hosts, they do not shed this parasite which only completes it’s life cycle in a carnivore host. Therefore beavers can not spread this parasite in their faeces (or therefore be tested for parasite eggs via faecal screening), and can not be treated for this parasite via ‘worming’. Post-mortem examinations should incorporate investigations for this parasite through examination for liver cysts (Barlow et al. 2011). A blood test for beavers for the presence of this parasite has been developed (Gottstein et al. 2014); previously, screening for this parasite in live beavers involved combined ultrasound and laparoscopic investigation, particularly of the liver and abdominal organs, as was done for wild-caught beaver of unknown origin within the River Tay catchment (Campbell-Palmer et al. 2015).

Franciscella tularensis is a bacterium that can be found in beaver blood, faeces, organs and body fluids. This bacterium can be passed to humans via handling infected beavers, or water sources containing a dead infected beaver, or through biting insects such as mosquitoes and ticks which have fed on the blood of infected beavers. The resultant disease can be fatal, with septicaemia developing rapidly in some cases. It should be noted that this bacterium is not currently present in Britain, and therefore serological and or faecal culture screening is advised for imported beavers. It has been reported predominantly in North American compared to Eurasian beavers (Wobeser et al. 2009).

Yersinia pseudotuberculosis is a bacterium commonly found in any rodent and may be recovered from beavers (Nolet et al. 1997; Gaydos et al. 2009). It is generally carried in the gastrointestinal tract but may occasionally result in septicaemia in mammals and birds, particularly rodents, primates and some ruminants. It can also produce a chronic wasting disease with granulomatous changes in the gastrointestinal tract. Yersinia enterocolitica may also result in septicaemia and gastrointestinal disease and has been isolated from North American beavers (Hacking and Sileo 1974).

Salmonella spp. may be carried by any mammal and may result in zoonotic transmission to humans, causing diarrhoea and vomiting. Beavers, as mammals, may become persistent carriers and shedders of this bacterium, although it is uncommon in our collective experience (Rosell et al. 2001). Faecal culture is recommended.

Campylobacter spp. may also be carried by any mammal, including beavers, and may result in zoonotic transmission to humans, causing diarrhoea and vomiting, but is again uncommon (Rosell et al. 2001). Faecal culture is recommended.

Bacillus piliformis is a bacterium causing Tyzzer’s disease, which is common in rodents in the wild and in captivity (Wobeser et al. 2009). It can result in acute septicaemia and death, or in a chronic wasting disease with granulomatous lesions in the liver and intestinal tract. It is passed via the faeco-oral route and may be detected in carriers or persistently infected animals in the faeces. It is uncommon in beavers.

Leptospira spp. may be carried by rodents, including beavers (Nolet et al. 1997). This zoonotic disease is already common in British wildlife, and can cause interstitial nephritis. It is transmitted through urine and mucocutaneous junctions. It may be tested through serological analysis using monoclonal antibody tests for servars of pools 1–6 in the first instance.

Trichophyton mentagrophytes is mainly found in rodents, which may carry it without clinical signs. Colloquially it is referred to as ‘ringworm’. Other species of Trichophyton and Microsporum spp. may also cause disease. Fur-brushing for culture in dermatophyte media is advised to assess for carrier status. This organism is widespread in the UK and Europe.

Adiaspiromycosis (Emmonsia spp.) is a yeast which has been reported in beavers and has been seen in other semi-aquatic and fossorial species, such as European Otters and Hedgehogs (Erinaceus europaeus) (Morner et al. 1999). It affects the lungs, and results in pneumonia. Beavers with respiratory disease should be screened by chest radiographs and broncho-alveolar lavage to determine the causal organism.

Hantavirus has never been reported in beavers; but in theory, as any rodent, they may act as a reservoir. It is known to be a problem in rodents, particularly rats, and has been reported in the UK (Jameson et al. 2013). The infected animal persistently excretes the virus in saliva and urine. It can be zoonotic, and produce haemorrhagic fever with renal failure. In North America, a pulmonary form has also been reported. Polymerase chain reaction tests on urine and saliva may be used to screen rodents. Serology may be used to determine exposure.

Rabies virus has also not been reported in Eurasian beavers but may affect any mammal. Screening of the live animal is not currently possible, so any imported beavers to the UK should be sourced from rabies-free areas or quarantined according to current Rabies Importation Order (as amended) directions.