CHAPTER 16

COLOSSUS OF ROADS

In downtown Brooklyn, the real harbinger of things to come was neither the embattled Fort Greene Houses nor that alcazar of postwar liberalism—the long-delayed Brooklyn Civic Center—but rather the asphalt passage between the two. Wholly absent from earlier schemes for the civic center, the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway became a key piece of the downtown renewal plan crafted by Robert Moses, for it was vital to the highway system he had long envisioned for the region. Originally called the Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway, the twenty-three-mile motorway drove a path through the city every bit as destructive as the later, more highly publicized Cross Bronx Expressway. By the time construction on the artery was finished in 1950, Gotham’s road grid was fully woven into the extensive web of motor parkways built earlier in Westchester and across Long Island. Moses was well on his way to achieving one of his oldest dreams—to “weave together,” as he famously put it, “the loose strands and frayed edges of New York’s arterial and metropolitan tapestry.”1

If, as we saw in chapter 4, the parkway was a Brooklyn invention, the modern highway was a product of the Greater New York metropolitan region. The word highway itself was first officially used in Kings County, in a document dated June 1654 that made reference to Kings Highway. It was in Westchester County in the early 1920s that the essential elements of modern highway design—limited access, grade-separated crossings, and smooth flowing curves, all enabling the sustained high-speed operation of motor vehicles—first appeared, in the pathbreaking trio of the Bronx, Saw Mill, and Hutchinson River parkways. Progenitors of the American interstates, they were the first roads anywhere designed for the pleasure of the motoring public. The Westchester parkways were studied by engineers from Germany, China, and Australia, replicated throughout North America and around the globe. Indeed, there is not a highway in the world without some of their DNA. In its original form, the parkway was meant to be not a commuter arterial, but rather a scenic reservation threaded with a drive for the leisurely—and exclusive—use of passenger automobiles (buses, like trucks, were prohibited from the start, complicating later claims that parkway bridges were made low on purpose to prevent the nondriving poor from using parks and beaches). The parkway was literally a way through a park. Like an extruded version of Central Park, it was meant to spirit one away from the city—from the “cramped, confined and controlling circumstances of the streets of the town,” as Frederick Law Olmsted put it—by imparting an immersive, almost cinematic sense of travel through a vast pastoral landscape. This was, of course, mostly stagecraft and illusion. In reality, the parkway corridor was just a narrow strip of land, in places just a few hundred feet wide. But it was richly garnished with rustic fences, signs and light standards, and romantic, low-slung bridges dressed with ashlar stone, while off-site scenes disruptive of the pastoral reverie—factories, commercial districts, apartment buildings, adjacent neighborhoods—were artfully screened by berms and lush plantings of trees and shrubs. The parkway was thus both a bold step forward and a nostalgic glance back—the machine age in tweeds or, as Marshall Berman memorably put it, “a kind of romantic bower in which modernism and pastoralism could intertwine.”2

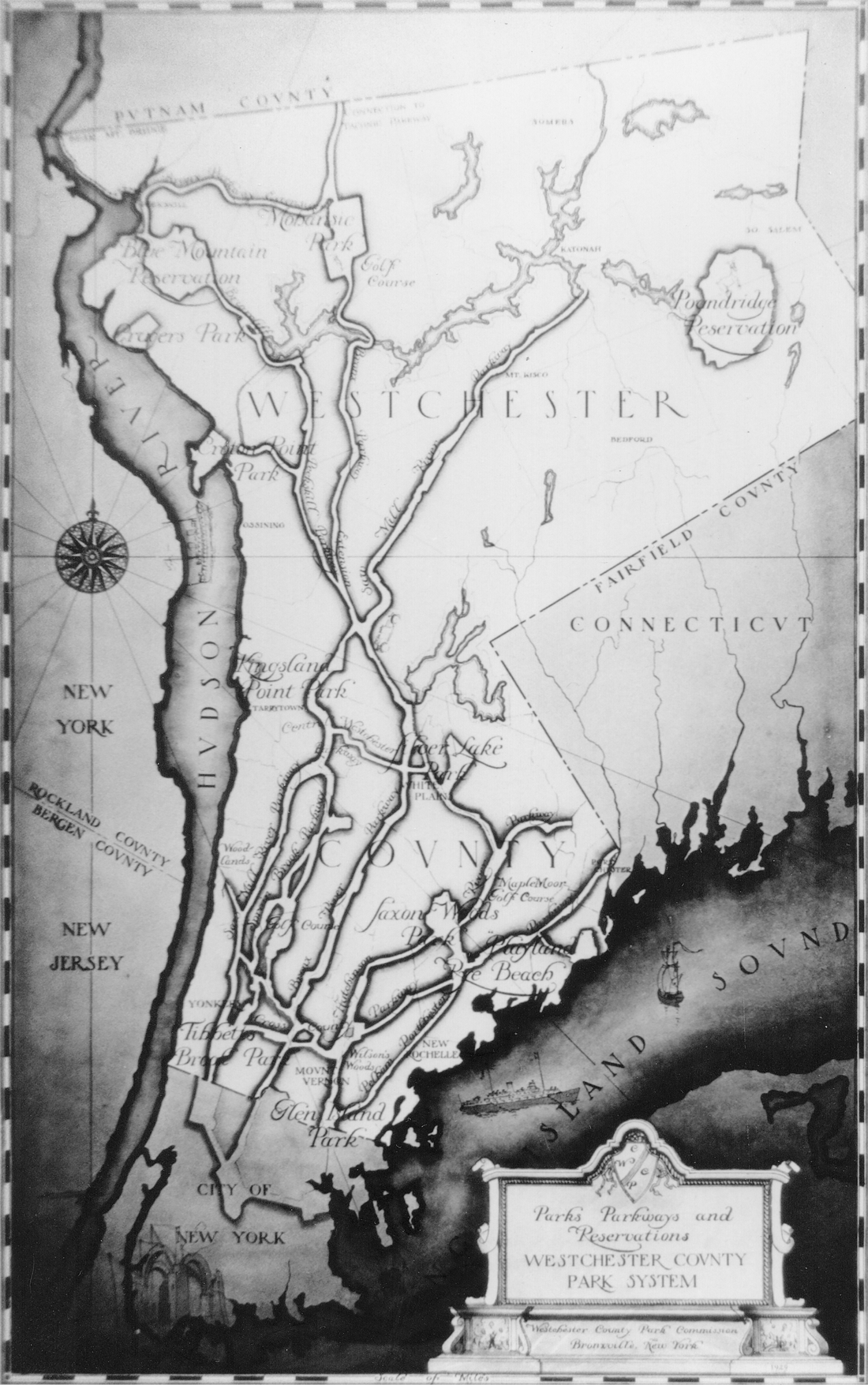

Equally innovative was the way these early parkways were used to structure a region-wide system of parklands and open space, creating in Westchester County the first park system of the motor age. It was specifically this—the motorway as regional parks-and-recreation infrastructure—that caught the eye of Robert Moses, whom Governor Al Smith had placed in charge of a new statewide parks agency in 1924. Moses modeled both the Long Island State Park Commission and the earlier New York State Council of Parks on the Westchester County Park Commission, and tapped the design genius behind its parks and parkways—Gilmore D. Clarke—to help him develop a sand-and-sea replica of the Westchester system for Long Island. Clarke, as we’ve seen, first met Moses while supervising construction of the Bronx River Parkway and later planned the Brooklyn Civic Center with partner Michael Rapuano. A decade before Moses brought Clarke to New York City, he tried to recruit the landscape architect to the Long Island State Park Commission. Though Clarke declined the job, he agreed to give lantern-slide presentations about his Westchester work to Long Island civic groups. Clarke later advised Clarence C. Coombs and a fellow veteran of the American Expeditionary Forces, Henry Lee Bowlby, in laying out the first Long Island parkways. He also sent one of his Westchester acolytes—Melvin B. Borgeson—to help draft plans for Jones Beach State Park, on which he was a consultant.3

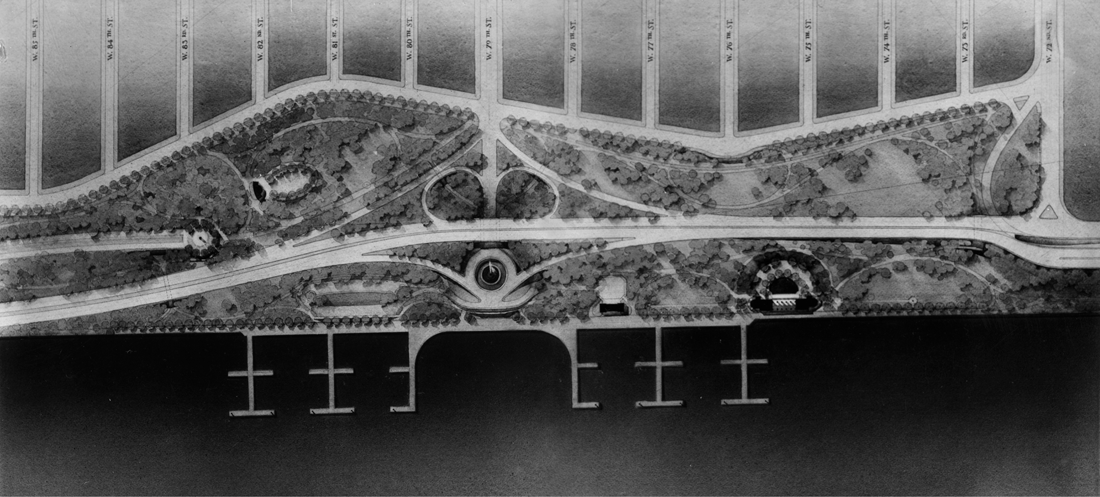

By 1935, with the suburbs north and east of town laced with state-of-the-art motorways, New York struggled to make do with a street grid designed for horse carts and carriages. Traffic congestion was so bad that planners feared for the city’s future as an economic powerhouse. For Moses, lacing Gotham with modern parkways, linking the metropolis by road to the nation at large, was a keystone ambition of his career, one that he first unveiled in February 1930 as chairman of the Metropolitan Park Conference—and that he acted on within days of taking office as the first citywide commissioner of parks. The first of these—the Henry Hudson Parkway—linked Manhattan and the Bronx to Westchester County via the Saw Mill Parkway. A project Moses had dreamed about for decades, work on the road began in early 1934, with the northernmost section opening two years later. Like its Westchester antecedents, the Henry Hudson was much more than just a vehicular thoroughfare. One of the hallmarks of motor parkway design as it evolved in Westchester was the provision of a rich array of leisure and recreation facilities along the route for use by the nonmotoring public—trails, picnic areas, ball fields, playgrounds. For Moses, too, such amenities were vital—at least at first. In his own words, parkways were “long ribbon parks with landscaped edges providing passive and active recreation for all age-groups resident nearby.”4 The southernmost section of the Henry Hudson was especially well endowed in this regard. It was part of a massive overhaul of Olmsted’s old Riverside Park—the West Side Improvement—that fused city, park, and motorway into a seamless whole. At Seventy-Ninth Street, Clarke and Rapuano and architect Clinton F. Lloyd created an extraordinary multileveled roundabout—officially the “79th Street Grade Crossing Elimination Structure” (carefully worded to tap federal funds for removing dangerous road-rail intersections). There, parkway access ramps and walking paths were spun around a Romanesque sunken plaza with a fountain in the center and a terrace overlooking the Hudson (today the Boat Basin Café). Elsewhere the Henry Hudson Parkway was padded with playgrounds, ball courts, and athletic fields, all framed by the same Italianate grid of London plane trees that Rapuano used at Cadman Plaza and Bryant parks. The West Side Improvement was highway planning at its best, a splendid union of city, citizenry, and the motorcar.5

Watercolor rendering of the Westchester County Park System, 1928. Westchester County Archives.

That high note would be struck again in Brooklyn, though under very different circumstances. It was there that Robert Moses built the most ambitious parkway project of his career—that shoreline route proposed as early as 1911 by Brooklyn’s minister of improvement, the Reverend Newell Dwight Hillis, and later urged by the Regional Plan Association as part of a “Parkway Circuit in South Brooklyn.” Originally called the Brooklyn-Queens Circumferential Parkway, the thirty-six-mile route would ultimately consist of four signed sections through Brooklyn and Queens—the Shore, Southern, Laurelton, and Cross Island parkways. Moses personally renamed the route the Belt Parkway shortly after construction began in 1938, reportedly because Queens borough president George U. Harvey could neither spell nor pronounce “circumferential.” Mayor La Guardia called it “New York’s first Ringstrasse,” while others favored “Lynque Parkway”—a playful homophone emphasizing the road’s linkage of Brooklyn and Queens. No road offered more amenities for communities along the route than the Belt Parkway, which is why—along with its fifty-eight bridges—the project cost nearly as much as Hoover Dam. In a letter to Reagan “Tex” McCrary of the New York Daily Mirror (who later produced the “American house” display at the 1959 United States Exhibition in Moscow, setting off the Nixon-Khrushchev kitchen debate), Moses described the Belt as “not just an automobile roadway,” but “a narrow shoestring park running around the entire city and including all sorts of recreation facilities”—ball fields, basketball courts, and many miles of bike path. He implored one of his superintendents, Allyn R. Jennings, to keep in mind that such “incidental . . . features are just as important as the parkway itself,” especially for “people in the neighborhoods along the route, present and future, who do not have automobiles.” With this great profusion of public amenity—3,550 acres of parkland in all—the Belt Parkway was hailed “the greatest municipal highway venture ever attempted.”6

Michael Rapuano, watercolor rendering of Henry Hudson Parkway and Riverside Park, December 1935. This section of Rapuano’s immense drawing shows the parkway from West Eighty-Fifth Street to West Seventy-Second Street, including Clinton F. Lloyd’s roundabout and fountain court at Seventy-Ninth Street (Boat Basin Café). From Detail Plans and Estimated Cost of Construction . . . for the West Side Improvement in Riverside Park (1936). Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

However innovative, the Belt was not the first trailblazing thoroughfare in Brooklyn. Nor was it the first conceived as part of a greater park system, or even to be called a parkway. As we saw in chapter 4, Olmsted coined the term to describe the three great pleasure drives, based on Haussmann’s Parisian boulevards, that he proposed to extrude Prospect Park through still-rural Brooklyn and Queens and even back to Central Park via a bridge at Roosevelt Island.

After World War II, with car sales soaring and a new culture of speed and efficiency in place, the humanism of Olmsted’s parkways and the motorways of the 1930s was largely set aside. Long, flowing spiral curves were pulled straight; lushly planted parkway reservations were pared down to the barest minimum; bike paths, walks, playgrounds, and ball fields were scrapped. Partly this was because, by 1945, the “easy” pieces of the arterial tapestry had all been woven—routes along the shoreline, often on filled land, like the Belt and Henry Hudson, or through farmland, parks, or cemeteries like the Hudson, Interboro (Jackie Robinson), or Grand Central parkways. Connecting up the remaining dots now involved punching through some of the most densely built urban terrain on the Eastern Seaboard—lower Manhattan, the South Bronx, and downtown Brooklyn. The longest and most costly of these—the Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway—began with the construction of the Gowanus Parkway prior to World War II. A transitional project, it was meant to extend the Belt Parkway north from Bay Ridge through Sunset Park as part of a grand arterial loop Moses hoped to build through Brooklyn and Queens. But the Gowanus was nothing like the Belt or the earlier scenic motor parkways. Instead, it was up high and arrow-straight, riding atop the steel piers that once carried the BMT Third Avenue Elevated from downtown to Sixty-Fifth Street (and on new supports north of Thirty-Eighth Street). Because the roadbed was much wider than the railway, hundreds of buildings had to come down on both sides of the street. And while Third Avenue had been shadowed by the el since the 1890s, it flourished nonetheless as the commercial core of Sunset Park’s large Scandinavian community. The shade cast by elevated tracks is light dappled and moves with the sun, like that of forest trees. The shade cast by an elevated roadbed is as fixed and unbroken as night. It “buried the avenue in shadow,” writes Robert Caro; “and when the parkway was completed, the avenue was cast forever into darkness and gloom.” Seduced by Moses’s ingenuity in repurposing the old el, the Times missed the larger point—that the Gowanus, despite its name, had scuttled nearly every design principle that distinguished the American parkway. “When Commissioner Moses finds the surface of the earth too congested for one of his parkways,” it rationalized, “he lifts the road into the air and continues it on its way.” New York was, after all, just “too heavily built up for a leisurely, landscaped parkway.” Time to get tough with all that silly urbanism cluttering the path of automobiles! And trucks, too: insofar as it was a nominal “parkway,” only passenger cars were permitted on the Gowanus, so Moses widened Third Avenue from four to ten lanes to handle all the truck traffic generated by the still-busy industrial waterfront. Within a decade, not only Third Avenue—once home to seven movie theaters, scores of shops, stores, restaurants, and cafés—but much of Sunset Park would be spiraling toward abandonment and blight. Whatever survived was finished off by the late 1950s, when the Gowanus was widened from four to six lanes and officially named what it had been all along—the Gowanus Expressway.7

Cover, Gowanus Improvement, Triborough Bridge Authority, 1941. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

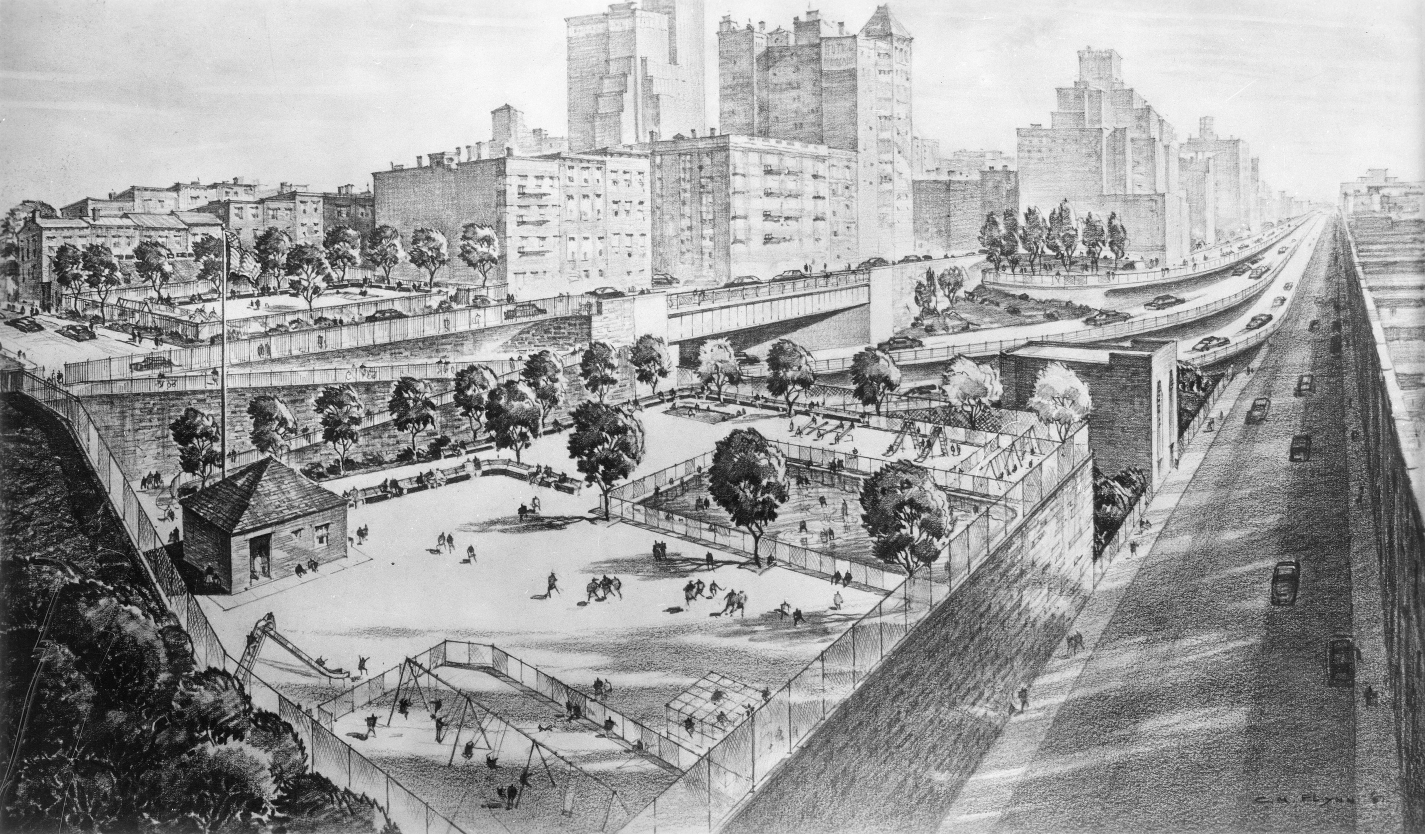

Worse was in store for the older, denser, poorer neighborhoods north of Sunset Park—the large working-class community of South Brooklyn (parts of which were rebranded Carroll Gardens and Cobble Hill as the area began gentrifying in the 1960s). Here a new colossus of roads would be built—not overhead like the Gowanus, but in a mile-long trench down Hicks Street from Hamilton to Atlantic avenues. The Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway would extend the Belt-Gowanus system north toward Astoria, eventually joining the Grand Central Parkway to provide “a convenient and rapid connection,” explained the Times, “between congested Brooklyn districts and popular routes leading to the World’s Fair, as well as Long Island parks and seashore.”8 Moses positioned the project as one of four “vital gaps” in the region’s arterial system that he sought to fill on Washington’s dime. Bending geopolitics to serve his will, he announced a $65 million program of road building on Armistice Day 1940, ostensibly to “facilitate the defense of New York City in war.” Left unfilled, Moses argued, these arterial lacunae would invalidate two decades of public works, for all those bridges, tunnels, and parkways built since the 1920s “could not adequately cope with both military and essential civilian requirements in wartime without the four proposed highways.” This was a tautology Moses would deploy again and again in the postwar era: unlocking a full return on earlier highway investments required investing in more of the same. Filling these gaps—the Harlem River Drive, a Pelham–Port Chester Express Highway (southern end of the New England Thruway today), and an expressway across lower Manhattan were the others—would open the city to “ponderous units of mobile war machines” and “mass military manoeuvers” while at last realizing Moses’s decades-old dream of a fully integrated system of metropolitan arterials. If the city took no action, Moses warned, Gotham might have to choose between food and freedom; for “if the streets are to be kept open for the inhabitants to survive, they cannot be commandeered for military use and defense transportation without disaster.” Moses, always shovel-ready, promised that work on all four segments could begin immediately and be done in a year, using round-the-clock shifts and a “speeded-up” condemnation process.9

Construction on the BQE came in bursts, with the first section—from Meeker Avenue in Greenpoint over the Kosciuszko Bridge to Queens Boulevard—opening in the fall of 1939. In South Brooklyn, Hicks Street was approved for conversion into a multilane arterial by the City Planning Commission in May 1941. At first it was to be simply widened, from 60 to 160 feet, with twin carriageways separated by a narrow median and flanked by service roads and sidewalks. But an Ocean Parkway it was not; for “it is proposed ultimately,” noted commission chair Rexford Tugwell, “to depress the central roadways below the level of the service roadways and to introduce grade separations . . . for express traffic in this highway.” Title to some 250 parcels on the west side of Hicks Street was secured by late August, and demolitions began within weeks. Construction on this and other sections of the BQE was halted with America’s entry into the war. Not until August 1946 did work begin on a “six-lane depressed highway down the center of widened Hicks Street,” with twin twenty-eight-foot service roads, twelve-foot sidewalks, and bridges to carry streets across at Union, Sackett, Kane, and Congress streets. With South Brooklyn thus gutted, how would this python of a motorway cross Brooklyn Heights? In map view the most obvious route was to simply stay the course: continue the BQE in a Hicks Street ditch straight north to the Brooklyn Bridge. Heights residents lived in fear of just this—that Moses would drive his road north and split the gracious old neighborhood like Solomon’s baby. And so when surveyors were seen fiddling with theodolites and transit rods on Hicks Street in early September 1942, the neighborhood was set abuzz like a boot-kicked beehive. The Brooklyn Eagle called the planned road “shocking,” while the Brooklyn Heights Press pulled out its biggest font to DENOUNCE EXPRESS HIGHWAY, claiming readers were “shocked beyond recovery.” Calmer souls knew that only a fool would incur the huge costs of condemning Hicks Street mansions when an easier route was at hand—around the Heights to the west along the steep Furman Street embankment. Moses understood this better than anyone. Aside from a self-serving quip years later—that he was talked out of going “through the Heights” by borough president Cashmore—there is no evidence that Moses seriously meant to run his road up Hicks Street. At best, the alignment was considered only briefly in the project’s early route-vetting stage. As one of Moses’s most trusted engineers, Ernest J. Clark, put it, none of the alignment options “except the one around Furman Street” met expressway standards, and most involved cutting through “very expensive property and churches.” Furman Street was clearly “the most logical way to go.”10

The Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway (BQE) trenched along Hicks Street in South Brooklyn, showing Union and Sackett street overpasses. Parks Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Fear and outrage over Hicks Street alignment of Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway, Brooklyn Heights Express, September 25, 1942. Roy M. D. Richardson Collection, Brooklyn College Library Archives and Special Collections.

Hicks Street would have also been politically costly. This was, after all, no hardscrabble immigrant district like Red Hook, but a neighborhood as well off as it was well connected. While the glory days of the Heights were past, it still had real power in 1940—the soft-spoken, old-money power of club and boardroom. A list of residents in and around Columbia Heights compiled in April 1943 reads like a page from the social register—Sturgis, Talmadge, Hamilton, Fairbanks, Parke, Hale, Edwards, Atwater, MacKay. There is not a single Jewish, Italian, Irish, Greek, Polish, or Chinese name among them.11 Moses had already been stung by the moneyed WASPs of Brooklyn Heights. Given his penchant for grudges and Machiavellian nature, it is very plausible that Moses directed his engineers to make a big show of surveying Hicks Street simply to provoke the community—as payback, perhaps, for its role in ending his Brooklyn-Battery Bridge dream several years earlier. Among the well-placed souls he faced in that fight was first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, who twice denounced the Moses span—an “eyesore perpetrated in the name of progress”—in her New York World-Telegram “My Day” column, evidently at the behest of friends on the Heights. By playing coy with the truth, Moses gained a strategic advantage as well: threatening the community with the Hicks Street alignment virtually guaranteed that any alternative would be eagerly approved. Introducing Furman Street as an apparent substitute for the dreaded Hicks Street route made Moses seem to be yielding to community will, while Heights residents convinced themselves it was their timely action that saved the day. Indeed, there was virtually no opposition to the “new” alignment, the one Moses almost certainly meant to build all along. “Representatives of a dozen Brooklyn business and civic organizations,” the Times reported of the sole planning commission hearing on the project on March 10, 1943, “were unanimous in approving the proposed route.” Proof that Hicks Street was just a diversion comes by way of a map, published the previous year in the Triborough Bridge Authority’s Gowanus Improvement brochure, that clearly shows the future BQE running along the Heights waterfront. Even earlier, in a June 1941 New York Times article about extending the Gowanus Parkway north, borough president John Cashmore explained that it was “the intention of the city . . . to extend this express highway route . . . to Furman Street and by way of Furman Street to a connection with the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Meeker Avenue bridges.”12

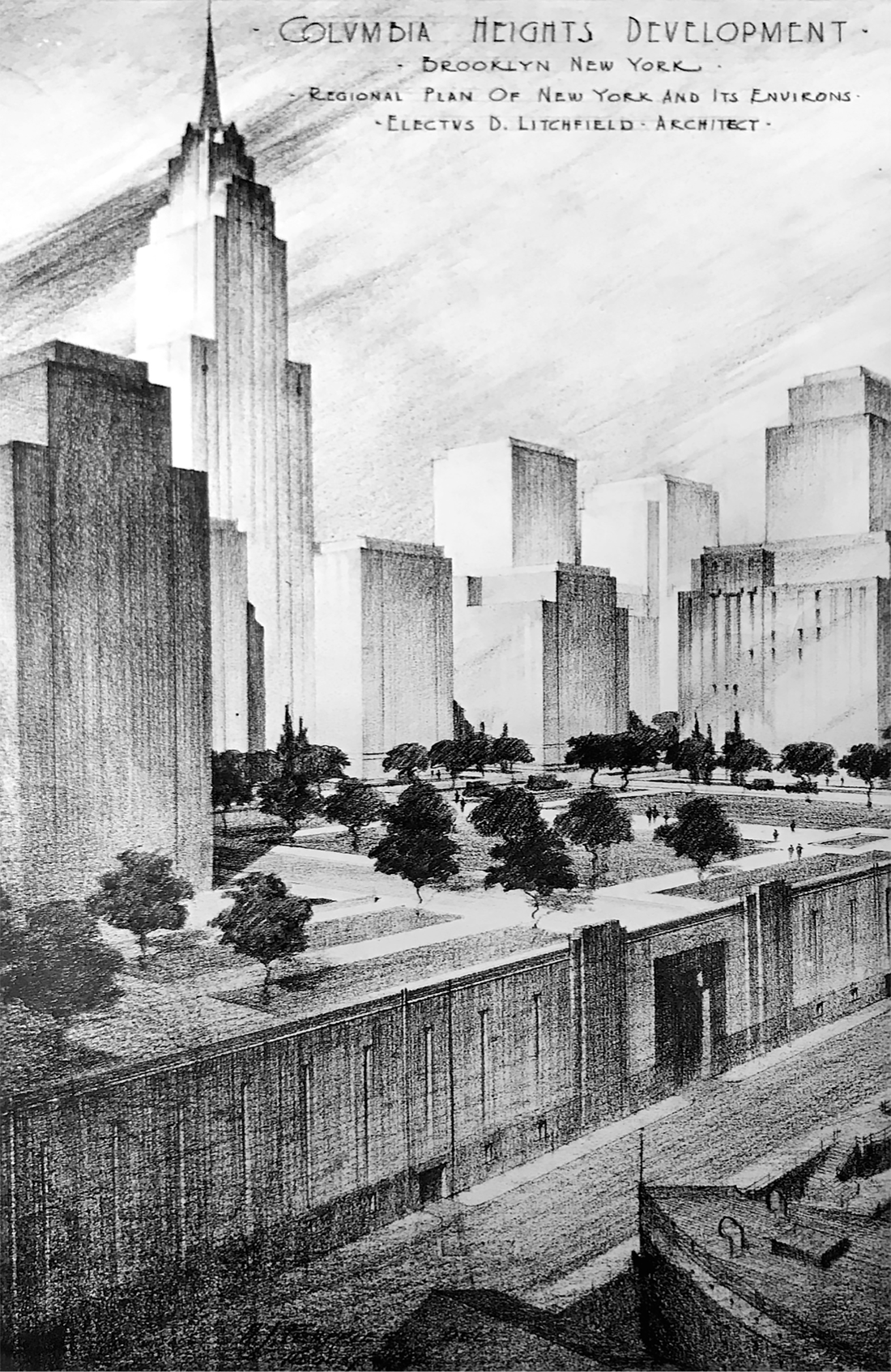

Given all this, it is poetic justice of a sort that Moses is blamed to this day for having nearly destroyed Brooklyn Heights with his expressway. Heights lore has it that only prompt action on the part of the Brooklyn Heights Association—the venerable body founded by the Reverend Hillis—saved the neighborhood from the same ruination that befell Sunset Park, Red Hook, and the South Bronx. Colorful tales abound, too, of heroics and selflessness on the part of influential Heights residents. One of the most persistent involves the Brooklyn-born typewriter heiress Gladys Underwood James. As the late Heights chronicler Henrik Krogius put it, James organized a “dinner of persuasion” to which she invited Moses and two other local doyennes. At some point in the evening, the good woman trotted out “diagrams and maps” and proceeded to convince the autocratic Moses “that the [Hicks Street] route would be fatal to the neighborhood, and that the highway must be put along Furman Street.” But as Krogius later discovered, James was not even a Heights resident until 1948, when she and her husband—Darwin James III—purchased Two Pierrepont Place. In any case, an expressway down Hicks Street was hardly the most extreme proposal floated for Brooklyn Heights in the decade before World War, II. That came instead, ironically, not from Demon Moses but from the pious progressives of the Regional Plan Association, who endorsed a mind-boggling scheme by architect Electus Darwin Litchfield in 1931 to remedy the presumed “obsolescence of large numbers of houses on Brooklyn Heights.” How? By razing every last structure on all the blocks west of Willow Street—purging in a single pass some of the most magnificent residential architecture on the Eastern Seaboard. In its place would rise a phalanx of three-hundred-foot-tall apartment buildings. Their immense scale would have cowed even Albert Speer. At the base of these towers, Litchfield—president of the Municipal Arts Society and a descendant of Edwin Litchfield, developer of Park Slope—proposed a formal park atop Furman Street, built on a plinth with a four-lane thoroughfare tucked underneath.13

This idea for a combined road and promenade at Columbia Heights was not new in 1931. As we saw in chapter 10, the Reverend Hillis had proposed a “boulevard one hundred feet wide, on the level of the gardens in the rear of the Columbia Heights houses” some twenty years before. Though he was the first to envision a joint promenade and drive, plans for a “Harbor View Terrace Park” had circulated at least a decade earlier. Elaborated in a lengthy piece in the May 10, 1903, issue of the New-York Tribune, the “imposing park or terrace” above the Furman Street embankment would run from Middagh Street to Joralemon Street and command “an unobstructed view of New-York Harbor.” At intervals along its great retaining wall there would be “semi-circular, turretlike stone platforms, like those along Riverside Drive, but more ornamental.” Columbia Heights property owners were predictably “not overjoyed with the scheme.” Promoters—including the Municipal Arts Society and some two thousand “leading business and professional men of the borough”—attempted to bully the holdouts, warning that failure to build the park “will mean the erection of large apartment houses upon this location within twelve months.” Homeowners on Columbia Heights already had a long history of fighting attempted takings in the public interest. As early as 1827, none other than pioneer Heights developer Hezekiah Pierrepont proposed creating “an open promenade for the public . . . from Fulton ferry to Joralemon Street,” but his own neighbors quashed the idea. Robert Moses refused to brook such opposition, especially from the rich, and under his autocratic rule the old idea of a Heights promenade was finally made real.14

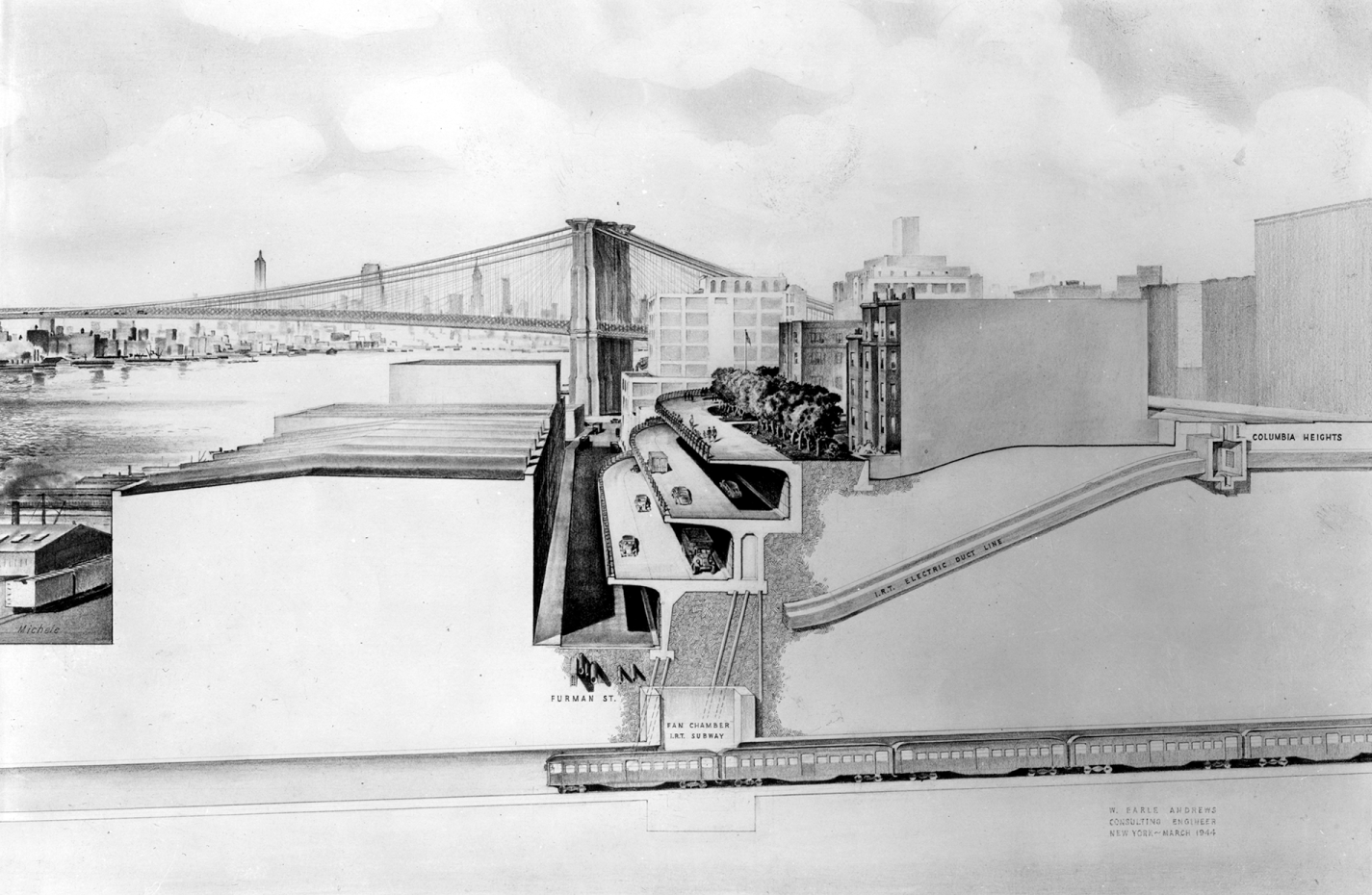

At the March 1943 City Planning Commission hearing, the BQE was presented as a single broad platform elevated above Furman Street at roughly the level of Columbia Heights. Roy M. D. Richardson—Heights Association president and a Wall Street lawyer (who lived at 218 Columbia Heights)—suggested that the road be built instead as “a double-decker . . . covered on top.” This would not only require taking less land along the embankment, but “keep to a minimum . . . noise and fumes” while enabling Columbia Heights homeowners to have their backyards “re-created over the covered highway.” Moses had a similar scheme in mind, but where Richardson and his neighbors dreamed of private gardens, Moses envisioned a grand public promenade, from which the breathtaking vista of lower Manhattan could be enjoyed by more than a few well-heeled elites. A full month before the public hearing, his trusted engineering consultants, Andrews and Clark, had prepared plans for an ingenious cantilevered highway structure topped by a deck with room enough for both private gardens and a public promenade. It was a quantum improvement over Litchfield’s bloated podium or Hillis’s Ocean Parkway on stilts. This idea, too—stacking the highway lanes one above the other—had itself been proposed before. In 1939 site planner Fred W. Tuemmler was retained by the City Planning Commission to prepare drawings for a “Brooklyn-Queens East River Express Highway.” His work, published the following year, called for a partly cantilevered stacked highway structure along Furman Street, with the upper road at roughly the level of Columbia Heights but without any promenade or even sidewalks. It was left to a team of Moses consultants—led by Andrews and Clark and backed by the omnipresent Clarke and Rapuano—to recognize that a series of cantilevered decks topped with a promenade would transform a clunky piece of arterial infrastructure into a masterpiece of urban design.15

Electus D. Litchfield’s solution to the “obsolescence of large numbers of houses on Brooklyn Heights,” 1931. The immense podium would replace the warehouses along Furman Street, what is today Brooklyn Bridge Park. From Thomas Adams, Regional Plan of New York and Its Environs, vol. 2 (1931).

Section-elevation of cantilevered deck structure looking north at Clark Street, Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway (BQE), 1944. Rendering by Julian Michele. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

It’s long been debated who deserves principal design credit for the cantilevered viaduct and promenade, and every line of inquiry leads to the same conclusion: like all public works of the Moses era, it was the product of many hands and minds. That said, it is probable that Michael Rapuano was the first to envision the highway cover as a grand viewing terrace. This was certainly the contention of Clarke and Rapuano partner Domenico Annese, a veteran of the Long Island State Park Commission who had once worked for Clarence C. Coombs. And it stands to reason; for not only was Rapuano one of the most gifted spatial designers of his generation, but he had particular expertise in the architectonics of steeply sloping sites. It was Rapuano who helped translate the rugged bluffs below Riverside Drive into a symphony of terraces and platforms, and who—years earlier as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome—spent months studying that masterpiece of cliffside design, the Villa d’Este in Tivoli. Prior to World War II, recipients of the Rome Prize in landscape architecture were required to produce detailed measured drawings of great Renaissance villas. Queen of Italian gardens, the Villa d’Este was an elusive subject, owing to its sheer scale and complexity; wrestling the terraced titan onto paper took hundreds of hours of work in field and at the drawing board. Today a UNESCO World Heritage site, the complex was built in the 1560s by the Ferrarese cardinal Ippolito II d’Este, who had architect Pirro Ligorio erect a palace over an old monastery and transform the hillside below into a fountain-splashed cat’s cradle of platforms and promenades. Soaring concrete arches and retaining walls, visible only from the valley below, made the seemingly effortless play of space possible. The gardens inspired a legion of artists over the centuries, from Piranesi to Franz Liszt, and tutored a generation of landscape architects in the mechanics of topography. “There is enough in that one garden,” Daniel Burnham observed, “to furnish profitable food for thought to all landscape men in America.”16 Rapuano’s exquisite watercolor renderings of the Villa d’Este, completed in 1928, were the basis of the Italian government’s later restoration of the garden complex. It requires no great leap of imagination to see the similarities between the Heights promenade and the expansive viewing terrace atop the Villa d’Este, high above the Lazio Plain. Rapuano’s hand is evident at a finer scale too. The layout and appointment of the promenade was commissioned to Clarke and Rapuano, where the latter took responsibility for it. Rapuano employed there one of his signature motifs—a scroll or volute—to terminate both north and south ends of the promenade, a design move he had used previously at Bryant Park and Battery Park (neither of which survives).

Perspective rendering of Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Heights Promenade by C. M. Flynn, 1951. Photo Archive, New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

Michael Rapuano, watercolor section-elevation through the Villa d’Este, Tivoli, c. 1929. Photographic Archive of the American Academy in Rome.

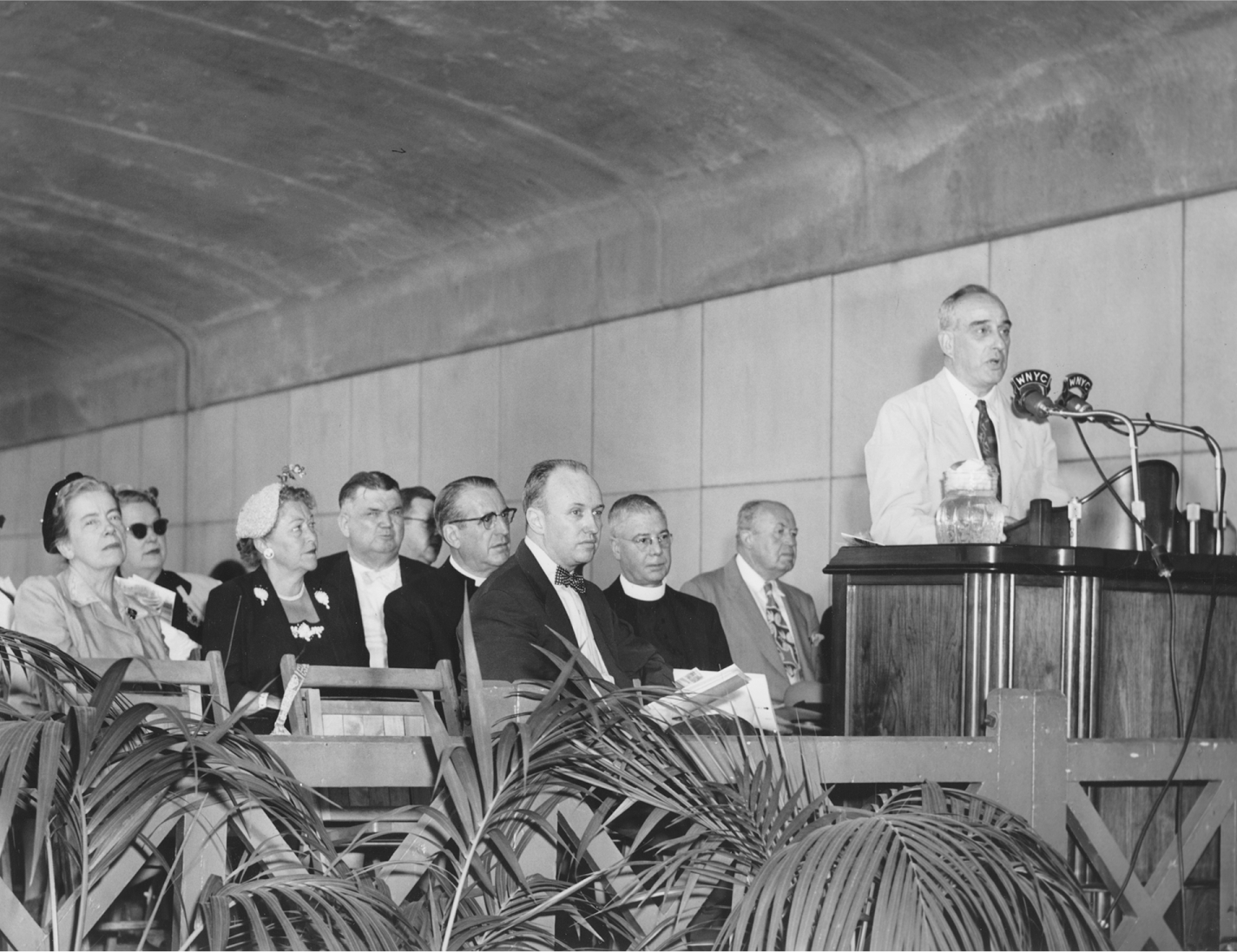

The Red Hook portion of the Brooklyn-Queens Connecting Highway opened on May 25, 1950, along with the Brooklyn-Battery (Hugh L. Carey) Tunnel—still the longest vehicular tunnel in North America. A caravan of “500 official automobiles” carried dignitaries over the new road from the tunnel ribbon cutting in lower Manhattan to a luncheon at the Hotel Bossert on Montague Street. The Furman Street section—stalled the previous autumn while some three hundred families were relocated from buildings south of Joralemon Street—was finished not long afterward, with the promenade itself opening on October 7, 1950. At a ribbon-cutting ceremony that December (complete with benedictions by a minister, rabbi, and priest) borough president Cashmore called Moses “the modern Leonardo da Vinci.” It was hyperbole, to be sure; but Moses had indeed created an extraordinary piece of urban infrastructure here—one that both solved an arterial problem and gave New York one of its finest public spaces. Lewis Mumford, a critic not easily impressed by anything to do with Moses or the motorcar, admitted that the viaduct and promenade “must be counted among the most satisfactory accomplishments in contemporary urban design.” Exhausted by the project’s more heroic aspects, he focused on an exquisite little space at the foot of Orange Street—the Fruit Street Sitting Area formed by Rapuano’s scrolled terminus at the promenade’s northern end. Here the great space reached “a breathless architectural climax,” wrote Mumford; “From one side of this circle, a reverse spiral leads upward in a ramp to the street. Within the circle, there are benches and trees, all arranged in the same circular pattern, while the stone paving consists of circular bands of contrasting textures—broken stone, hexagonal blocks, cobblestones—forming a complicated pattern with which the eye could play for hours.” All this yielded such a “deeply satisfying composition” that Mumford set down his pen, pleasantly spent. “Perhaps it is just as well to leave my account of these great reconstructions at this point,” he sighed; “When one has reached a moment of perfection, there is no use pushing any further.”17

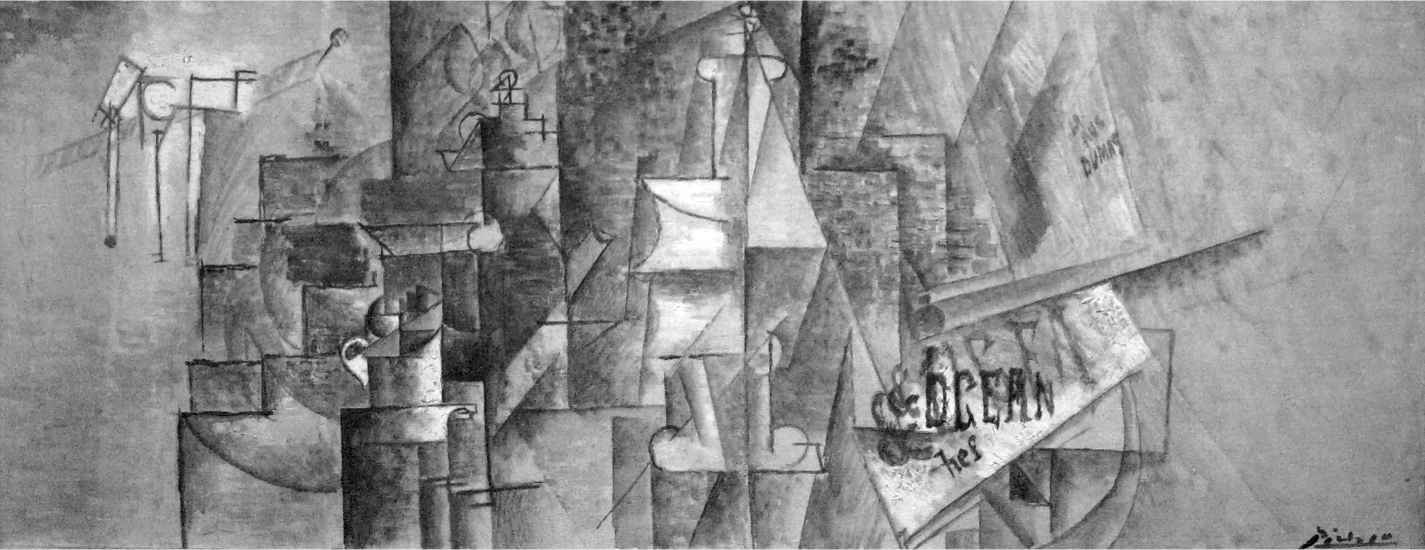

In Brooklyn Heights, the BQE bestowed a great blessing on the city. Elsewhere it took much and gave little in return. The enormous cost of the cantilevered viaduct and promenade was effectively subsidized by poorer communities along the route, which were deprived of much-needed parks and playgrounds as project funds dried up. In the Heights, too, the BQE was hardly evenhanded. Swinging east past the promenade, the road obliterated several blocks of the working-class North Heights at Middagh, Poplar, and Vine streets. Among the casualties was February House, the bohemian rookery made famous by Carson McCullers. Scores of homes were caught in the road’s yawning right-of-way, but February House lay directly in the highway’s path—as if Moses had purposely tweaked the alignment to blow away the storied den of libertines (the house stood where the BQE’s eastbound lanes exit the Columbia Heights underpass, at about the level where Paul Bowles would have had his basement piano). Also sacrificed for the expressway were the “Quaker Row” townhouses—104 to 110 Columbia Heights—erected by James Cromwell Haviland in the 1840s. It was from a window in the last of these that Washington A. Roebling monitored progress of the Brooklyn Bridge after falling victim to Caisson’s disease. The homes later came into the possession of Haviland’s grandson, Hamilton Easter Field. Born in the Heights, Field studied architecture at Columbia before moving to Europe, where he immersed himself in the Parisian art scene. He befriended many avant-garde artists, including Pablo Picasso, whom he commissioned in 1909 to create an eleven-piece mural for his Brooklyn Heights library—an ensemble that was only partly executed and never installed (one painting, Nude Woman, is at the National Gallery of Art; another, Pipe Rack and Still Life, is at the Met). Field was later art critic for the Brooklyn Eagle and opened a gallery and art school—the Ardsley School of Modern Art—in Quaker Row, joining several of the homes together at the first floor. It became a key venue by which Americans were introduced to European and Japanese modern art. Field’s first big show—Important Exhibition of Modern Art: Impressionism, Post Impressionism and Cubism—opened in December 1916, featuring work by Man Ray, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin.18

The highway and the city: perspective rendering of cantilevered highway structure and Brooklyn Heights Promenade by Greville Rickard, 1945. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

Robert Moses speaking at dedication of the Brooklyn Heights Promenade and Furman Street section of Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, October 1950. Brooklyn Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

February House (with pediment) at western end of Middagh Street shortly before demolition, c. 1949. New York City Municipal Archives.

There were other noteworthy tenants in the building and on the street. Not long after Field’s death in 1922, poet Hart Crane began renting rooms at 110 Columbia Heights, exulting at what he described as “the finest view in all America.” He set up a desk close to Washington Roebling’s window, and there began his epic tribute to the span—The Bridge (finished, ironically, in a basement apartment up the street). John Dos Passos moved to the building shortly after Crane, and the pair often dined and drank together at a local Italian eatery in the winter of 1925. It was at 110 Columbia Heights that Dos Passos launched his most celebrated novel, Manhattan Transfer. Thomas Wolfe, Asheville-born author of Look Homeward, Angel, resided briefly across the street in a building spared by a hair’s breadth when the BQE came through. As it plodded on toward the Navy Yard, the expressway consumed hundreds more buildings, mostly homes of common folk and wholly erased from collective memory. Between Jay Street and Hudson Avenue, acres of heavily built land were cleared just to accommodate the coiled ramps joining the BQE to the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges. This was the last, fatal blow to the old Fifth Ward, a place long bedeviled by the ill winds of improvement and renewal. And it came right on the heels of another convulsive burst of modernity dumped in the neighborhood’s lap—the Admiral Farragut Houses.19

Pablo Picasso, Pipe Rack and Still Life on a Table (1911). Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society.

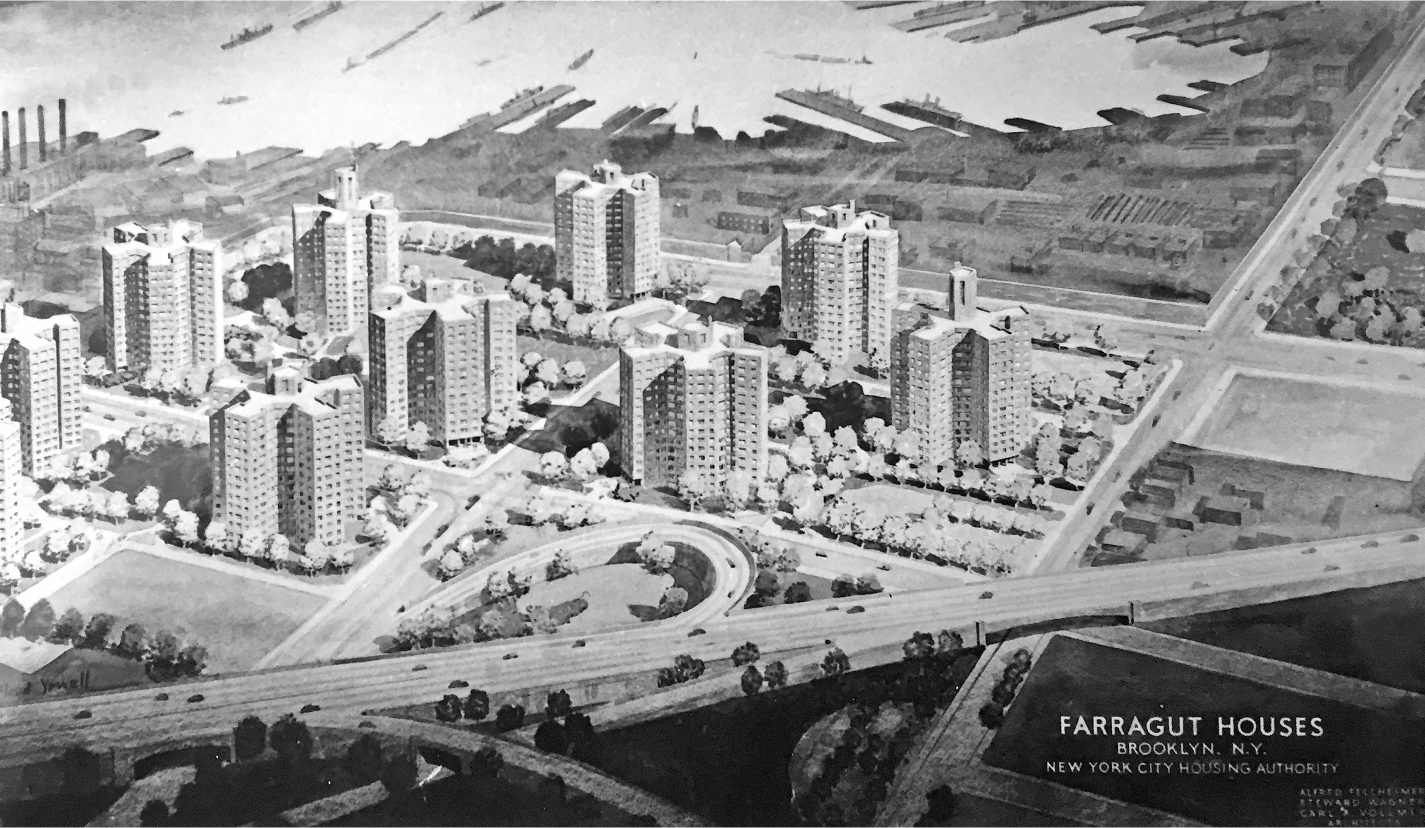

While not as vast as the earlier Fort Greene project, the Farragut complex obliterated all the blocks around the entrance gate to the Navy Yard—including, for better or worse, notorious Sands Street. The grim fleet of hub-and-spoke towers, set adrift on superblocks, was the work of Alfred T. Fellheimer—a onetime classicist, incredibly, who had helped design Grand Central Station. The project should have been named the Panoptic Houses, given the chilling resemblance of its barbican towers to eighteenth-century English philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s scheme for a total-surveillance penitentiary. Making room for the Farragut Houses and the BQE together consumed some forty-five acres of the most heavily built blocks in Brooklyn, displacing scores of families (including my uncle and grandmother) and laying waste to a community that—for all its problems and against all odds—had survived for more than a century. The expressway was elevated now, lifted on pylons after passing beneath the Manhattan Bridge. But it was not lifted much. Riding lower and wider than the Gowanus Expressway, the BQE crushed the life out of Park Avenue; it was a looming rampart that made everything in its path a dark and forbidding no-man’s-land. Every neighborhood touched by the BQE from here to the Queens line was doomed to the same “gyre of destruction” that made Sunset Park a slum years before—including the struggling Fort Greene Houses. As it roared past the Navy Yard, the BQE swung north again, marching through Williamsburg and Greenpoint like a latter-day Sherman’s army. Photographs of the newly cleared right-of-way recall scenes of bombed-out Lebanon. This was urban warfare. As Mumford observed, the impact of arterial construction on the fabric of a city was very much like that of “the passage of a tornado or the blast of an atom bomb.” A six-lane expressway is wildly out of scale with all but the most industrial cityscapes, and arterials like the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway “must not be thrust,” he cautioned, “into the delicate tissue of our cities; the blood they circulate must rather enter through an elaborate network of minor blood vessels and capillaries.” But “what is Brooklyn to the highway engineer,” Mumford lamented, “except a place to go through rapidly, at whatever necessary sacrifice of peace and amenity by its inhabitants?”20

Perspective rendering of Farragut Houses, 1947. New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

A man with the ego and drive of a Robert Moses is never satisfied. Nor is highway building generally an enterprise with intrinsic closure. Roads can go on forever, and they generate a momentum all their own; build one and suddenly, inevitably, others seem vitally needed. This was especially the case in the postwar era, when Americans were buying cars by the millions and Detroit was the nation’s economic polestar. Each completed highway—wide open and traffic free at first—convinced that many more people to take up the wheel, increasing traffic volumes and soon prompting another round of road building. Lewis Mumford was the first to call this ruinous cycle, whereby the remedy “actually expands the evil it is meant to overcome.” The highwaymen, he feared, would not stop until that “terminal point” was reached, when all civic life was forced from the city, leaving behind “a tomb of concrete roads and ramps covering the dead corpse.”21 Something more sinister was at work, too. Noting that the limited-access highway made it possible “to go from Coney Island to Buffalo without encountering a traffic light,” Mumford conjectured that “once a system like that takes shape, it has an abstract, hypnotic fascination, which leads to the next step of complementing it by a system that will lead the motorist from Washington to Maine with the same smooth facility”—even if this meant scrambling “the living quarters of tens of thousands of people.”

Thus, at a time when our cities can be made livable again only by isolating their residential neighborhoods from through traffic and rebuilding our decaying systems of mass transportation, our public authorities are busily breaking down the structure of neighborhoods and parks and devoting public funds to private transportation and private speculative building.

“As a formula for . . . ruining what is left of our great cities,” Mumford concluded, “nothing could be more effective.”22

In postwar America, a roaring economy, cheap oil, and widespread suburban development made the highway juggernaut nearly unstoppable—and nowhere more so than the New York City of Robert Moses. In the 1930s, motorways were woven thoughtfully into the metropolitan fabric; roads served city and citizen. Now Moses and his cadre of engineers began to see the city as little more than an obstacle to a future of seamless, flowing rivers of cars—the very future General Motors presented so seductively in its Futurama exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. What was needed, Moses expounded after winning a GM essay contest on highway building, was the temerity and boldness to drive “modern expressways right through and not merely around and by-passing cities.”23 And Moses was as good as his word. By 1956 he had completed the Prospect and Major Deegan expressways. Work was well under way on the Cross Bronx Expressway, which opened in stages between 1955 and 1963. The Clearview and Van Wyck expressways were completed in the early 1960s, the latter eventually extended north and south to the Whitestone Bridge and John F. Kennedy Airport. The ill-starred Bruckner, last of the Mosaic pythons, dragged on for years—an “indeterminate artery,” Ada Louise Huxtable called it, that epitomized the turmoil and paralysis of New York City in the 1970s.24

The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway carves a path through Williamsburg, 1958. New York City Municipal Archives.

Just as the New Deal paid for the parkways of the 1930s, the postwar expressways were heavily subsidized by another federal initiative—officially the Eisenhower Interstate Highway program. Made law on June 29, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956 was among the most significant pieces of legislation of the twentieth century. It authorized billions in federal funds to help states construct a forty-one-thousand-mile matrix of asphalt—a National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, as Congress called it—that would eventually link up nearly all US cities with populations over fifty thousand. Substantially built in just over a generation, this “greatest and the longest engineered structure ever built” forever changed the lifeways and landscape of the United States.25 Ironically, Moses was at first opposed to a national highway system, believing it wasteful to run big roads “through many thinly populated sections of the country where no such super-highways are needed.”26 There were trains and planes for cross-country travel. “The only justification for superhighways and parkways,” he argued in a 1940 letter to Thomas H. MacDonald of the Bureau of Public Roads, “lies in their close relationship to metropolitan centers and substantial cities.”27 The whole point of this infrastructure, he avowed, was to ease congestion, and congestion was fundamentally an urban problem. But the postwar Moses was very different from the prewar model. Among other things, he changed his tune about a national highway system. Once it became clear that Uncle Sam could help fund his arterial dreams for Gotham, Moses threw his weight behind the Eisenhower interstate program. Most of his postwar expressways were built with huge infusions of federal cash, and all were eventually made part of that sprawling web of asphalt that changed forever the American landscape.