CHAPTER 18

BOOK OF EXODUS

Everybody who’s anybody is moving to Babylon.

—PATTY HASSETT

The 1960s left Brooklyn with a lot less than a kumbaya highway stretched across its strife-torn south. A sojourner returning after a decade abroad would have been stunned to find many of the borough’s most vital, venerated institutions dead or dying. The fifteen years between 1955 and 1970 were the most convulsive in Brooklyn history, a time of exodus and loss that left the borough a quaking shell of its former self. It was as if the wrecking balls of urban renewal so busy downtown had begun smashing the very temples of Brooklyn life and culture. The presses of the Brooklyn Eagle were stilled in 1955, leaving the most opinionated place in America without a mouthpiece of its own. As Pete Hamill has put it, the Eagle was never a great paper, but “it had a great function: it helped to weld together an extremely heterogeneous community. Without it, Brooklyn became a vast network of hamlets, whose boundaries were rigidly drawn but whose connections with each other were vague at best, hostile at worst.”1 The timing of the daily’s demise was itself extraordinary—folding just seven months before one of the biggest stories of the era: the Dodgers victory over the Yankees in the 1955 World Series. Two years later, almost to the day, the Dodgers themselves were gone. Their storied Flatbush ballpark, Ebbets Field, vanished not long after, cleared for a dreary housing estate. In 1964, just days before Thanksgiving, secretary of defense Robert S. McNamara announced that the 158-year-old Brooklyn Navy Yard would be shuttered, dooming thousands of jobs. That news came on the heels of another bombshell—that Steeplechase Park, last and greatest of Coney Island’s storied amusement grounds, would not open again after the 1964 season. Its cavernous Pavilion of Fun—Brooklyn’s own Crystal Palace—was purchased by Fred Trump, ostensibly for an apartment complex à la Miami Beach. On September 21, 1966—after the city denied him the requisite zoning changes (but before the nascent Landmarks Preservation Commission could designate the Pavilion a city landmark)—Trump hosted a boorish “V.I.P. Farewell Ceremony” at which guests were handed bricks to hurl through the great windows. He razed the structure a few weeks later, an act of vandalism that destroyed a memory-palace of the very people who made Trump rich.

By this time, all of Brooklyn seemed “shabby and worn-out,” wrote Hamill, “not just in the neighborhood where I grew up, but everywhere . . . The place had come unraveled, like the spring of a clock dropped from a high floor.”2 People were fleeing in droves. Brooklyn’s population had climbed steadily for a century, leveling off after World War II and peaking at 2.74 million in 1950—more than the populations of Los Angeles, Detroit, and Philadelphia at the time. The collapse began slowly but accelerated wildly in the 1960s. By the 1970s, the bleakest decade in modern New York history, more than 500,000 people had fled Kings County—a city the size of Atlanta gone in a generation. Precipitating this mass exodus was a Gordian knot of both push and pull forces, many of which were operating with equal ferocity in cities throughout the Northeast at the time. As we have seen, the postwar collapse of Brooklyn industry and resulting loss of tens of thousands of factory jobs yanked the keystone from the borough’s economic arch. There were many other factors; race, for one. The influx of large numbers of African Americans from the rural South and Harlem was, to put it gently, not a demographic shift met with joy and open arms by Brooklyn’s white ethnic community. They regarded the newcomers with the same skepticism and outright hostility that had been aimed at them a generation before by the Anglo-Dutch elite. And just as the borough’s old-line WASPs fled for Westchester and Long Island in the 1920s, so too now did the Irish, Jews, Italians, Greeks, and Poles. The nexus of race, crime, and white flight in New York City is a barbed and hazardous topic, but vital to understanding not just the postwar era but everything that came afterward—including the “discovery” of Brownstone Brooklyn by antiestablishment elites in the 1970s and the wholesale gentrification of once-shunned neighborhoods in the 1990s. In the fields of urban planning and American studies, it has long been an article of faith that racism and bigotry were the chief causes of the postwar flight to the suburbs—a population shift that deprived cities of billions in tax revenue, gutting their coffers and plunging them into a protracted era of fiscal crisis.

There was, to be sure, no shortage of racial hatred in Brooklyn; working- and lower-middle-class whites, especially, resented the influx of African Americans from the South—a demographic shift that began in the 1920s, but reached a fever pitch following World War II. But if racist loathing of the black Other drove some to abandon the old neighborhood, it was the calamitous unraveling of the borough’s social fabric in the 1960s—especially the rise of violent crime—that turned what might have been a trickle into a full-scale exodus. In all of New York, crime skyrocketed in the postwar years—a phenomenon that baffled police, politicians, and sociologists alike. To most observers, Gotham at war’s end seemed on the verge of a glorious era of peace and prosperity. Civic leaders were convinced that, just as the war had vanquished evil, New York would enter “a new era in which intelligence, education, and the insights of psychology and other social sciences,” wrote Roger Starr in The Rise and Fall of New York City, “would overcome most behavior problems . . . that full employment would eliminate crime.” Few indeed could have seen that, despite a booming national economy and high overall employment, “crime itself would, within twenty-five years, be regarded as New York’s most serious problem.” The statistics are grim. As Vincent J. Cannato notes in The Ungovernable City, between 1955 and 1965 murders citywide “increased 123 percent; robberies 25 percent; assaults 88 percent; and burglaries 31 percent.” And it was just the start. From 1960 to 1974, robberies soared by 255 percent, forcible rape by 143 percent, and aggravated assault by 153 percent. There were 58,802 incidents of violent crime in the city in 1965; by 1975 that figure had nearly tripled to 155,187. Murders in the same period shot from 836 citywide to 1,996—an increase of 139 percent. As James Q. Wilson and others pointed out, this upsurge came in spite of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society programs and War on Poverty and an unprecedented array of social welfare initiatives at every level of government. “If in fact crime resulted from poverty,” writes Philip Jenkins in Decade of Nightmares, “then it should surely have declined, or at least got no worse. Instead, crime rates had risen to historic highs.”3

Fairly or not, whites blamed the crime explosion on the city’s swelling black and brown underclass. In Brooklyn, the African American population more than tripled between 1950 and 1970, rising from about 208,000 to more than 650,000, while the number of Puerto Ricans citywide jumped from 187,420 to 817,712 in the same period. The disappearance of manufacturing jobs, owing to automation as well as factory closures, hit minority communities first and hardest. By the mid-1960s, unemployment among African American men in the eighteen-to-twenty-four age bracket was five times that of white men. The ego-shattering inability of bread-winners to find and hold a job not only mired families in poverty, but spawned a vexing array of social ills—single-parent households, truancy, youth gangs, prostitution, drug addiction. Blacks in the city suffered higher mortality rates than whites, paid more in rent for lower-quality housing, and were forced to contend with lesser schools, while median black household income was just 65 percent that of whites. In Brooklyn, conditions were especially bad in Bedford-Stuyvesant, which shifted from majority white to 85 percent black between about 1945 and 1960. Battered by urban renewal, hemmed in by redlining, and gutted by blockbusting real estate agents, the enormous neighborhood—really a vast assembly of neighborhoods forced under the racialized rubric of “Bed-Stuy”—was terra incognita to most New Yorkers until July 1964, when protests touched off in Harlem by the police shooting of a black student spread to Brooklyn.4

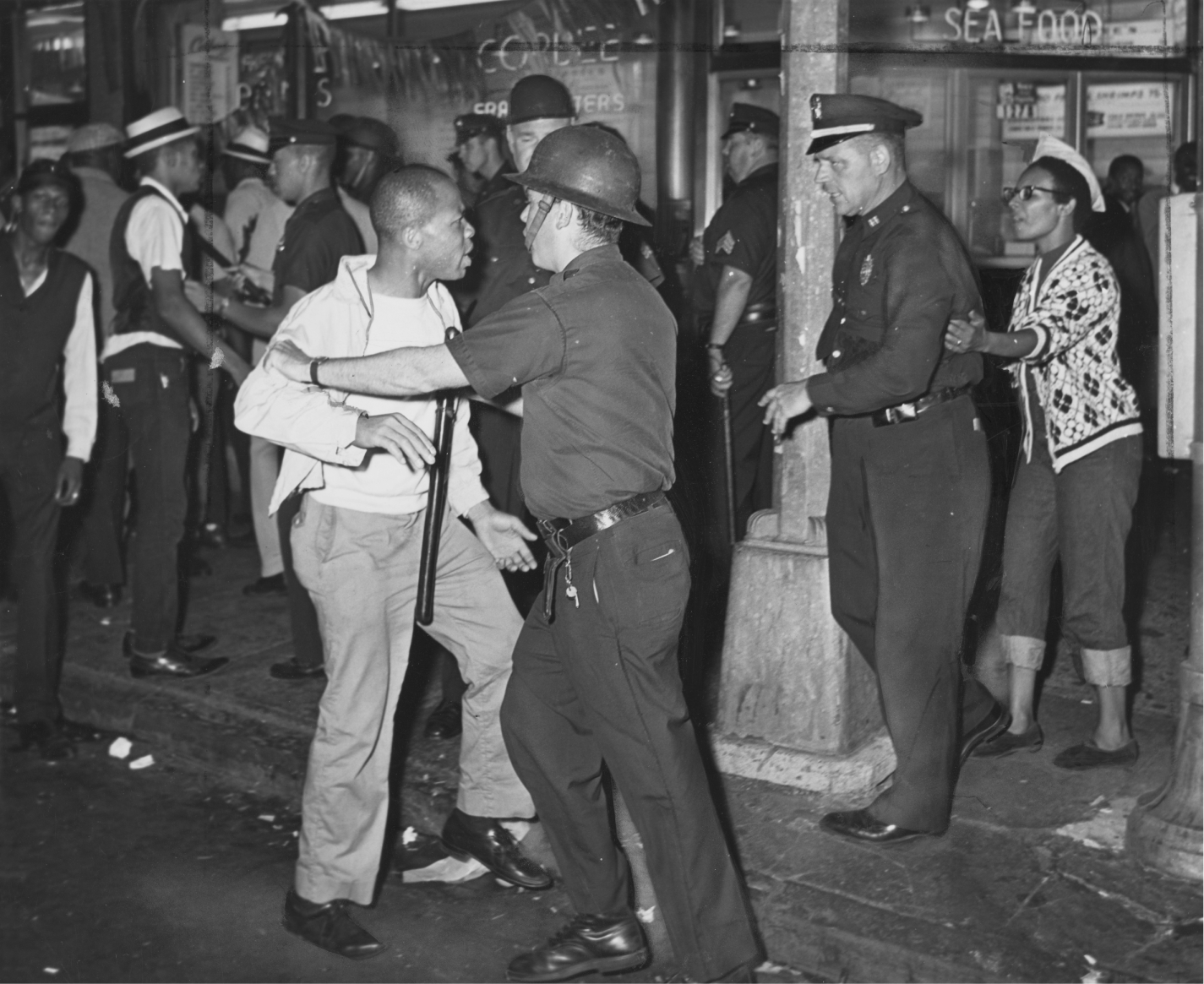

Several days of violence and looting ensued, centered on Fulton Street and Nostrand Avenue. Police, pelted with brickbats from rooftops, could do little to quell passions. Equally unsuccessful was the NAACP, whose sound truck was nearly overturned as lawyer George Fleary and other staffers begged for calm while handing out pamphlets exhorting, “Cool It, Baby.” Hundreds of shops were gutted and torched by the time peace was restored. Police arrested some 450 protesters; more than a hundred people were injured. The uprisings were the first of the civil rights era, and by summer’s end had spread to Rochester, Philadelphia, Jersey City, Paterson, Elizabeth, and Chicago. The violence rattled Brooklyn and took a toll on racial tolerance throughout the city. For all its liberal, Democratic leanings, the city’s white community—along with the majority of blacks—was unyielding when it came to the rule of law and order, concurring with Mayor Wagner’s avowal that it must be “absolute, unconditional, and unqualified.” In a New York Times survey conducted that fall, just weeks before the 1964 presidential election, 93 percent of white New Yorkers reported that the riots “had hurt the Negro cause,” while large pluralities in the white ethnic community—61 percent of Irish, 58 percent of Italians, and 46 percent of Jews—felt that the “Negro movement . . . was going too fast.” And while just 18 percent of whites citywide expressed support for Republican candidate Barry Goldwater, 27 percent asserted that they “had become more opposed to Negro aims during the last few months.”5

Clash between police and African American residents on Nostrand Avenue, Bedford-Stuyvesant, July 1964. Photograph by Stanley Wolfson. New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

However offensive to present sensibilities, the blame put on minorities was not wholly misplaced: a study of the 543 solved murder cases in New York City in 1966 revealed that 73 percent had been committed by blacks and Puerto Ricans. But if minorities were committing most of these acts, they were doing so largely within their own communities. An April 1967 article in the Times, published in the wake of several high-profile instances of black-on-white violence, showed that “violence against white people by Negroes is relatively infrequent both in New York City and nationally”—that the vast majority of violent crime victims were blacks themselves. Blacks in the inner city “had far more reason to be afraid,” writes Adam Shatz; for “they lived in poor areas where crime was more widespread, and where the police were often absent.” In Harlem, the Amsterdam News complained of “predatory thugs who bring terror to the streets,” with a 1968 report by the NAACP denouncing “the reign of criminal terror” and calling for harsher penalties for drug dealing and violent crime, better enforcement of antivagrancy laws, and more cops on the beat. “It is not police brutality,” argued the group, “that makes people afraid to walk the streets at night.” But perception is nine-tenths of reality, and reports like this did little to dissuade whites from seeing crime in starkly racialized terms. Increasing violence and social chaos “posed a classic case of cognitive dissonance for many whites,” writes Michael W. Flamm. “Intellectually, they knew that most blacks were not muggers; emotionally, they could not ignore the sense that most muggers seemed black. Adding to the racial tension and providing human faces to the grim statistics were a dramatic series of high-profile events and a disturbing number of sensational black-on-white crimes.” The most widely publicized of these was the March 1964 murder of Kitty Genovese outside her Kew Gardens home at the hands of Winston Moseley—a married African American father of two who later confessed to three other murders—and the rape and murder two months later of a popular Brooklyn schoolteacher, Charlotte Lipsik, by an illiterate teenager who went on to rape and kill an eighty-three-year-old woman in the Bronx before being caught.6

The ugly tangle of race and crime turned the very geography of the city plastic, with neighborhoods shape-shifting in response to black advance and white retreat. The boundaries of Bedford-Stuyvesant “progressively enlarged,” writes Michael Woodsworth, “to match the spreading radius of black settlement,” while nearby Flatbush—a middle-class Jewish district settled by émigrés from Williamsburg and the Lower East Side—contracted in response. A Times reporter probing its borders in 1968 was given as many answers as people he asked. “If you really want to know the truth,” one resident admitted, “today when people say ‘Flatbush’ they mean the place where the Negroes aren’t.” Attitudes on the street contrasted sharply with those in the halls of power and learning, where any linkage between race and crime was sanitized with euphemism and spoken of sotto voce. Indeed, “most liberal political leaders,” writes Jenkins, “tended to dismiss concern about violent crime as coded language for racial hatred and white supremacy.” Propinquity did nothing to warm whites to their new black neighbors; it had the very opposite effect. This contradicted prevailing social theory at the time, especially Gordon W. Allport’s “intergroup contact hypothesis,” which posited that tolerance and harmony would increase with proximity. Writing about working-class Italian-Jewish Canarsie a decade later, Jonathan Rieder noted that “physical closeness to blacks widened the moral and social chasm between them.” New Yorkers with little daily contact with poor blacks became their greatest champions; those closest to them physically and economically were the most hostile. As Cannato put it, “Enlightened views on race were easy to hold for whites who lived in the comfortable suburbs or in the doorman buildings of Manhattan.”7

As crime surged in the late 1960s, New Yorkers of every race, class, and ethnicity became prisoners in their own homes. In a December 1968 piece, journalist Michael Stern observed that fear was making people “live ever-larger portions of their lives behind locked doors.”

Feeling themselves besieged by an army of muggers and thieves, they are changing their habits and styles of life, refusing to go out after dark, peering anxiously through peepholes before opening their doors, side-stepping strangers on the streets, riding elevators only in the company of trusted neighbors or friends and spending large sums to secure their homes with locks, bolts, alarms and gates.8

Unease pervaded every aspect of life. “The fear is visible,” wrote David Burnham in the Times in June 1969; “It can be seen in clusters of stores that close early because the streets are sinister and customers no longer stroll after supper for newspapers and pints of ice cream. It can be seen in the faces of women opening elevator doors, in the hurried step of the man walking home late at night from the subway . . . in elaborate gates and locks, in the growing number of keys on everybody’s keyrings.”9 The effects on civic life were corrosive. “Since the very purpose of a city is to provide convenient access to the necessities and amenities of industrial civilization,” wrote Starr, “it is no exaggeration to say the crime that has emerged in New York City threatens the very existence of the city in its present form.” And it wasn’t just violent crime but “lesser offenses that make the streets and subways seem outlaw lands. The ordinary rules of civility have been lost.” Vandalism, including astonishing eruptions of graffiti that covered entire subway cars, signaled that “the quality of life, despite all the conscious agitation to improve it, has been soiled and damaged in far more crucial ways that none can control.” Anticipating the city’s “broken window” policing policies by decades, Starr surmised that to ignore low-level offenses “opens the city streets to further testing: If I can get away with this, what may I not do next?”10 The specter of crime and social collapse was magnified in impact by the chaos being unleashed at the very same time by vast urban renewal and highway projects. These, as we have seen, not only subjected residents to years of noise, dust, and congestion, but forced jobs out of town and eradicated rental housing that, however substandard, was at least cheap. Life in Brooklyn, never easy for those of little means, was fast becoming intolerable.

Nor were these purgative forces operating in a regional vacuum. As crime, racial tensions, escalating taxes and rents, and a deteriorating quality of life began pushing Brooklynites out, equally powerful forces were luring them to suburbs both in town and out. Many moved to the trolleyburbs of Brooklyn and Queens explored in chapter 13; others fled the city altogether, settling in the many new subdivisions then being built in New Jersey, Long Island, and Connecticut. Facilitating the exodus were all those splendidly engineered parkways, bridges, and expressways built by Robert Moses in the 1930s and after the war—the very infrastructure that dislodged as many city dwellers as it convinced to buy a car. Moses had built the roads to put the beaches and parks of Long Island and upstate New York within easy reach of the motoring middle classes. Now they became the taps that ran the population kegs dry. The flush of affluence in the postwar years, combined with cheap and abundant gasoline, created an army of new motorists. Weekend jaunts to “The Island” often involved touring a gleaming new subdivision, where many an urban denizen saw her future. For all its problems, it is unlikely that so many families would have left Brooklyn had not savvy developers like William and Alfred Levitt offered seductively affordable alternatives out beyond the city line. By streamlining supply chains, barring unionized labor, negotiating more flexible building codes, and applying mass production techniques similar to those pioneered by William Greve and Fred Trump, the Levitts were able to build 17,500 homes between 1948 and 1951 that sold for as little as $8,000 (about $80,000 in 2017). Underwriting by Uncle Sam in the form of low-interest home loans made the homes more affordable still. The GI Bill—formally the Servicemen’s Adjustment Act of 1944—made available an array of programs and services meant to smooth the transition of soldiers back to civilian life. The most celebrated of these was the tuition support that enabled countless servicemen to attend college, launch a professional career, and thus gain entry to the American middle class. Equally impactful was its provision of loan guarantees to cover the cost of purchasing a home—so long as that buyer was “a member of the Caucasian race,” as racist FHA restrictions then required. The legislation, meant to stimulate the economy via the homebuilding industry, offered nothing to those veterans who wished to rent in the city.

The Servicemen’s Adjustment Act transformed the housing market overnight, easing the postwar housing crunch and putting home ownership within reach of millions. Prior to World War II, less than half the households in America owned their own homes—a function of the huge down payments then required by lenders (between half and two-thirds of purchase price) as well as mortgage contracts obliging borrowers to pay back loans in less than a decade. Such terms made even buying a home on credit a privilege of affluence. Many needed no help at all. Between one-quarter and half of all homes sold before the war were purchased in full and free of debt.11 Uncle Sam changed all this by effectively underwriting projects like Levittown that opened the dream of suburban home ownership to the children of impoverished immigrants. Levittown’s cozy Cape Cod homes, bracketed by lawn and garden in front and back, appealed to that perennial American yearning for pastoral tranquility and the elixir of nature—little Monticellos far from the chaos of urban life and the “mobs of great cities,” as Thomas Jefferson himself put it. Derided from the start by the intelligentsia, mocked sanctimoniously by Malvina Reynolds and Pete Seeger, the “Little Boxes” of Levittown were nonetheless a proud mark of arrival and acceptance into mainstream America for working-class ethnics whose childhoods had been marred by the Depression, who came of age in a world wracked by war, who yearned for a modicum peace and prosperity and a chance to raise a family. The last thing these children of hardship wanted was yet another crisis—and the slow-motion collapse of Brooklyn’s social and physical infrastructure in the 1960s was just that. That their departure helped bring about that very collapse—pulling the tax-base rug out from under Gotham, stripping the city of a stable citizenry—only adds to the multivalent tragedy that was Brooklyn in the postwar era.

Long Island Lighting Company office and appliance store, Levittown, New York, 1953. Gottscho-Schleisner Collection, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The mass exodus of Brooklyn’s middle and working classes after World War II sealed the fates of many a borough institution, none more vital to Brooklyn’s identity and self-image than its merry band of the diamond, the Brooklyn Dodgers. The club started out in 1883 in the minor leagues, moving to the majors the following year and eventually joining the National League. It was known by almost as many names as it had players—the Grays, Superbas, Bridegrooms, Robins. Not until 1895 did sportswriters and fans alike start calling the team by a name that referred to the ostensible dexterity of locals in dodging Brooklyn’s swift, newly electrified streetcars. The Dodgers first played at two different ball fields named Washington Park on the edge of Park Slope, moving to Eastern Park in Brownsville in 1891, and returning seven years later to yet another Washington Park adjacent to the Gowanus Canal (near today’s Whole Foods Market on Third Avenue). By then the club was being managed by Charles Ebbets. Son of a bank president, Ebbets quit school to work as a draftsman in the architectural office of John B. Snook, designer of the original Grand Central Depot, and later sold penny novels for a publishing house. He joined the Dodgers organization as a bookkeeper and ticket-taker, but moved up fast; by 1900 he was on his way to majority ownership in the ball club. Ten years later he set out to build a new stadium for the team, the best and most modern in America. The site he chose was in a section of Flatbush known as Pigtown, then only sparsely settled but close to transit and in the path of future growth. Ebbets commissioned the architect son of a Gravesend minister, Clarence Randall Van Buskirk, to design the structure. The new field, which Ebbets modestly named for himself, sported a steel-frame upper deck and roof and a neoclassical façade. Fans entered through a marble rotunda with terrazzo floor over which hung a spider-like bat-and-ball chandelier, which—if ever found—would likely fetch as much as the entire stadium cost in 1913 ($750,000).12

Ebbets Field opened auspiciously with an exhibition game on April 5, 1913. Casey Stengel scored the first Brooklyn run; the Dodgers won the game. Fans flocked to the new ballpark; attendance records were broken. In 1916 the Dodgers took home a pennant and did so again in 1920. But in 1925 Charles Ebbets was felled by a heart attack, and his death brought an ill wind. A protracted legal battle over club owner-ship dragged through the Great Depression, wrecking what had been one of the most financially sound clubs in baseball. Its board of directors feuded constantly; management was inept. Out of luck and out of cash, the Dodgers reached bottom in 1937. “Phone service had been cut off because the bills were not being paid,” writes baseball historian Andy McCue; “The team’s office was crowded with process servers seeking payment. Ebbets Field was a mass of broken seats, begging for a paint job. Charles Ebbets pride, the beautiful rotunda, was covered with mildew.” But then came Leland Stanford MacPhail, an innovator who would transform the club over the next decade. As a college football coach in Ohio, MacPhail had developed the system of penalty hand signals still used today by referees. He later turned the Cincinnati Reds into a profitable baseball franchise by expanding radio broadcasts and introducing night games—the first in the Major Leagues. In Brooklyn, MacPhail hired still-popular Babe Ruth as a coach and named loudmouthed Leo Durocher as manager. He fixed up Ebbets Field and began broadcasting games on radio before either the Yankees or the Giants.13

The fans were soon streaming back. Attendance rose 37 percent in 1938. In 1940 the Dodgers led their league in attendance, setting a franchise record of 1.2 million attendees the following year. But the abrasive MacPhail made many enemies and was eased out of the organization by 1942. Replacing him was Branch Rickey, then general manager of the St. Louis Cardinals and the one who had recommended MacPhail to the Dodgers. A religious conservative who had once preached on the temperance circuit, Rickey was a respected figure in baseball—he invented the modern farm system, among other things—but he was not much liked. He was duplicitous, cheap, anti-Catholic, and anti-Semitic. And yet the much-flawed Rickey would make sports history just three years later by recruiting Jackie Robinson to the Dodgers, breaking baseball’s color line. With the game in good hands, the directors focused on strengthening its front office. For this, George V. McLaughlin, president of the Brooklyn Trust Company and the ball club’s biggest creditor, turned to a young Brooklyn lawyer he had mentored, Walter F. O’Malley. Within a few years Rickey and O’Malley not only were managing all aspects of the Dodger organization, but were majority owners of the club itself. They turned the team into a winner on both field and balance sheet. Rickey scored a moral victory by signing Robinson, but also landed a great player who drew new fans from the borough’s growing African American community. O’Malley negotiated innovative branding, royalty, and television deals that boosted the club’s bottom line; profits rose steadily each year from 1945 to 1949. On the diamond the team was at the top of its game, scoring two pennant victories between 1946 and 1950 and twice coming close.14

If integrating baseball was Rickey’s great project, O’Malley’s was to build the Dodgers a new ballpark—a matter he began studying as soon as he joined the organization in 1946. Ebbets Field, already past its expected thirty-year life span, was fast becoming a maintenance liability and could barely handle the huge crowds the Dodgers were drawing. Seats were splinter prone, bathrooms were obsolete, and parking in the surrounding neighborhood was scattered, scarce, and costly. O’Malley wanted a large modern stadium convenient to public transit but—more vital still—one that could also accommodate the increasing percentage of fans driving to Flatbush to catch a game. O’Malley retained one of the finest engineers in New York, Emil H. Praeger, to develop preliminary plans for a superstadium. Praeger was a Flatbush kid himself, a graduate of Erasmus Hall Academy and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He was also, like Clarke and Rapuano, part of the Robert Moses brain trust. Moses had appointed him chief engineer of the newly consolidated Parks Department in 1934, where his first job was to conduct an unprecedented survey of the entire city’s parks and open spaces. Praeger went on to design the Henry Hudson and Marine Parkway bridges and engineer the reclamation of the Flushing ash dump that Moses claimed as one of his greatest achievements. Praeger’s first project with O’Malley—designing a small field for the Dodger spring-training facility in Vero Beach, Florida—allowed the pair to test ideas for a superstadium in Brooklyn. Of course, such a high-profile venture—a modern home for one of the most popular clubs in baseball—drew the attention of many other creative souls. First among them was the media-savvy industrial designer Norman Bel Geddes.15

Jubilant crowd of boys at Ebbets Field, 1954. Photograph by Jules Geller. Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

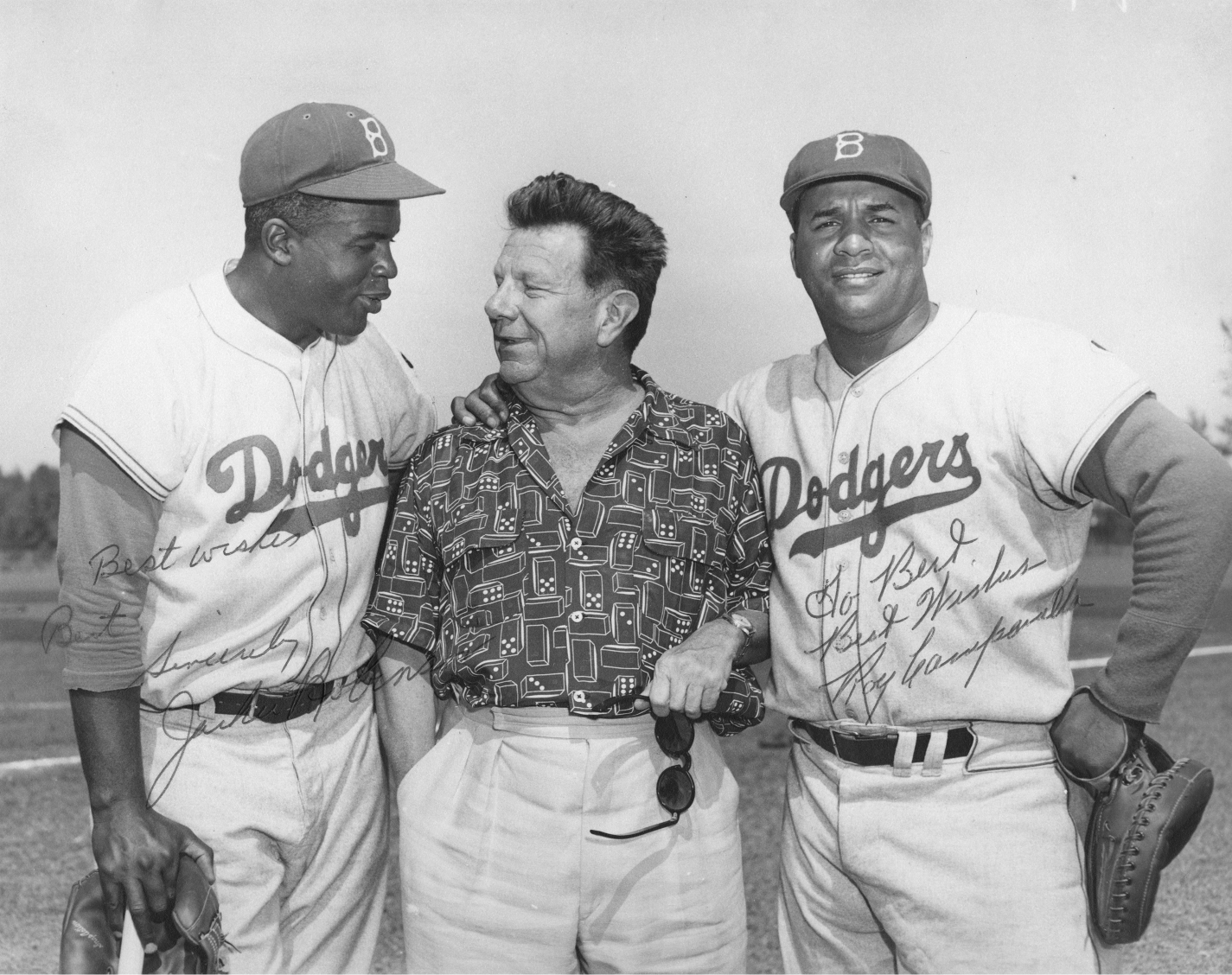

Norman Bel Geddes with Jackie Robinson (left) and Roy Campanella (right), c. 1952. Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin.

Bel Geddes had begun his career creating sets for the Metropolitan Opera and gained wide renown for his work on the 1939 New York World’s Fair. He first approached O’Malley in 1948, certain that a new Dodger stadium could be the capstone commission of his career. Jumping O’Malley’s light, Bel Geddes told reporters in March 1952 that he was already designing a state-of-the-art ballpark for Brooklyn. It would have rubberized seats and vending machines on every third seat back. Teams would play on an early version of Astroturf—“a synthetic substance to replace grass . . . which can be painted any color.” There would be seating for fifty-five thousand fans, expandable to ninety thousand for prize fights or conventions. All seats would be oriented toward the pitcher’s mound, and none would have an obstructed view. Lighting for night games would be indirect, eliminating glare. Bel Geddes continued working on his ballpark all summer, without O’Malley’s approval or even a site upon which to build it. That hardly mattered, for his “All Weather–All Purpose Stadium” was a self-contained spaceship of sport, sealed from both weather and the mean streets of Flatbush. A carapace-like retractable roof would put an end to the hated rain check (which Charlie Ebbets had introduced to New York baseball). A Collier’s article in September described the complex as designed to counter the impacts of television and suburbia, which together threatened to make the ballpark fan “as extinct as the bison.” Bel Geddes was America’s most persuasive prophet of automobility, the mastermind behind the General Motors “Futurama” exhibit at the 1939 World’s Fair, which envisioned a gleeful technotopian future of skyscraper cities linked by twenty-lane expressways. He understood better than most that the new Dodger stadium would have to be convenient to all those Brooklynites fleeing the city for the sprawling suburbs of Queens and Long Island.16

As O’Malley himself remarked, “The public used to come to Ebbets Field by trolley cars, now they come by automobile.” The old ballpark had depended on a patchwork of tiny parking lots that could, at best, accommodate seven hundred cars; the Bel Geddes scheme boasted a parking garage for seven thousand. And if easy parking wasn’t enough to lure suburbanites off their sofas, there were other amenities never before seen in a ballpark—including a modern shopping center beneath the stands. There, supermarkets, shops, and stores would serve fans as well as local residents, as would playgrounds where mothers “can place their youngsters in the hands of trained young men and women while they shop, or visit the doctor or dentist.” Fearful suburbanistas could drive their autos right into the stadium, hand the keys to a parking attendant, and even have the family car serviced while they watched the game. The getaway would be a cinch, too, with an array of lanes to permit “easy loading or unloading of 3,000 taxis, 400 buses, 1,500 private cars in a quarter of an hour.” All this seduced even the pragmatic O’Malley, who was soon penning odes of his own to the proposed stadium in the Eagle. But the exuberant Bel Geddes proved too much for this cigar-chomping backroom deal maker, whose agitated “No, no, Norman!” was becoming a daily refrain. The Rubicon was likely crossed when the designer insisted that the ball field be engineered to allow “conversion . . . into an artificial lake for motorboat and sailboat shows.” For better or worse, the buoyant Bel Geddes was out of the Dodger scene by the end of 1954.17

The following April, perhaps feeling this loss, O’Malley wrote to architect Eero Saarinen, asking if he might share “any photographs or technical articles” on Kresge Auditorium—the just-completed thin-shell concrete dome structure that Saarinen had designed for the MIT campus. The next month he read a magazine article on perhaps the only person in America who could outstrip Bel Geddes in scope of vision—the polymath futurist R. Buckminster Fuller, genius of the geodesic dome and the man who gave us the concept of “spaceship earth.” O’Malley wrote to Fuller on May 26, relating his ambition to erect a revolutionary all-weather stadium in Brooklyn, capped with a translucent dome. He wanted the stadium to be a game-changer; “I am not interested in just building another baseball park.” Fuller responded enthusiastically; the project promised to be the ultimate application of the kind of lightweight self-supporting, lattice-shell structure he had first experimented with at Black Mountain College in 1948 (and just received a patent for). Fuller and his design team had already worked out load calculations for a similar “clearspan enclosure” for the Denver Bears, and just months earlier he was retained by Minneapolis architects Thorshov & Cerny to explore options for enclosing a new Twin Cities ballpark (Metropolitan Stadium, demolished for Mall of America). Fuller proposed for Brooklyn the same “Octetruss” structural system he had recommended for Minneapolis, making possible a vast clearspan roof “skinned with translucent fiberglass petals opening and closing to the sky.” Inside, Fuller explained, a canted array of polyester-resin seating boxes—lightweight and “rotatably dumpable for cleaning purposes”—would enclose the field, affording fans “unprecedented altitude and view advantage.” Wrapped about the Octetruss exterior, meanwhile, would be “tiered parking balconies” that fans would access via a “spiral drive-yourself-up ramp.” Fuller closed his letter suggesting he and O’Malley attend a ballgame together to discuss plans.18

In late September, with the World Series just getting under way, O’Malley formally announced that Fuller would be collaborating with the Dodgers on a new stadium. The projected arena, reported the Times, would be “circular in shape and covered by a thin plastic dome,” 750 feet in diameter and rising to 300 feet above the pitcher’s mound—“high enough to cover a thirty-story building.” Passively cooled by “natural currents of air circulating beneath the dome,” it would be the largest clearspan structure ever built. A dedicated teacher, Fuller made the stadium the focus of a graduate design studio he taught that fall at Princeton University. O’Malley attended a review of their work just before Thanksgiving, marveling at a large-scale model of the stadium, its translucent dome anchored at five points and creating “a pleasant interior effect of the sort one finds in a greenhouse.” Inspired by one of Fuller’s lectures, Princeton MFA student Theodore W. Kleinsasser decided to make the stadium the subject of an independent master’s thesis. A Tennessee native, Kleinsasser had played football at Princeton as an undergraduate, returning to campus after a stint in the army as a paratrooper. Kleinsasser’s thesis arena, slightly smaller than Fuller’s, was presented on January 21, 1956, to a ten-member jury including O’Malley, Fuller, Praeger, and J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the Manhattan Project and head of Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Study. Perhaps the most memorable feature of Kleinsasser’s stadium scheme was a rooftop tramway to carry sightseers across the vast dome—a Sputnik-era recap of the cog railway that was to have inched around huckster-visionary Sam Friede’s great Coney Island globe.19

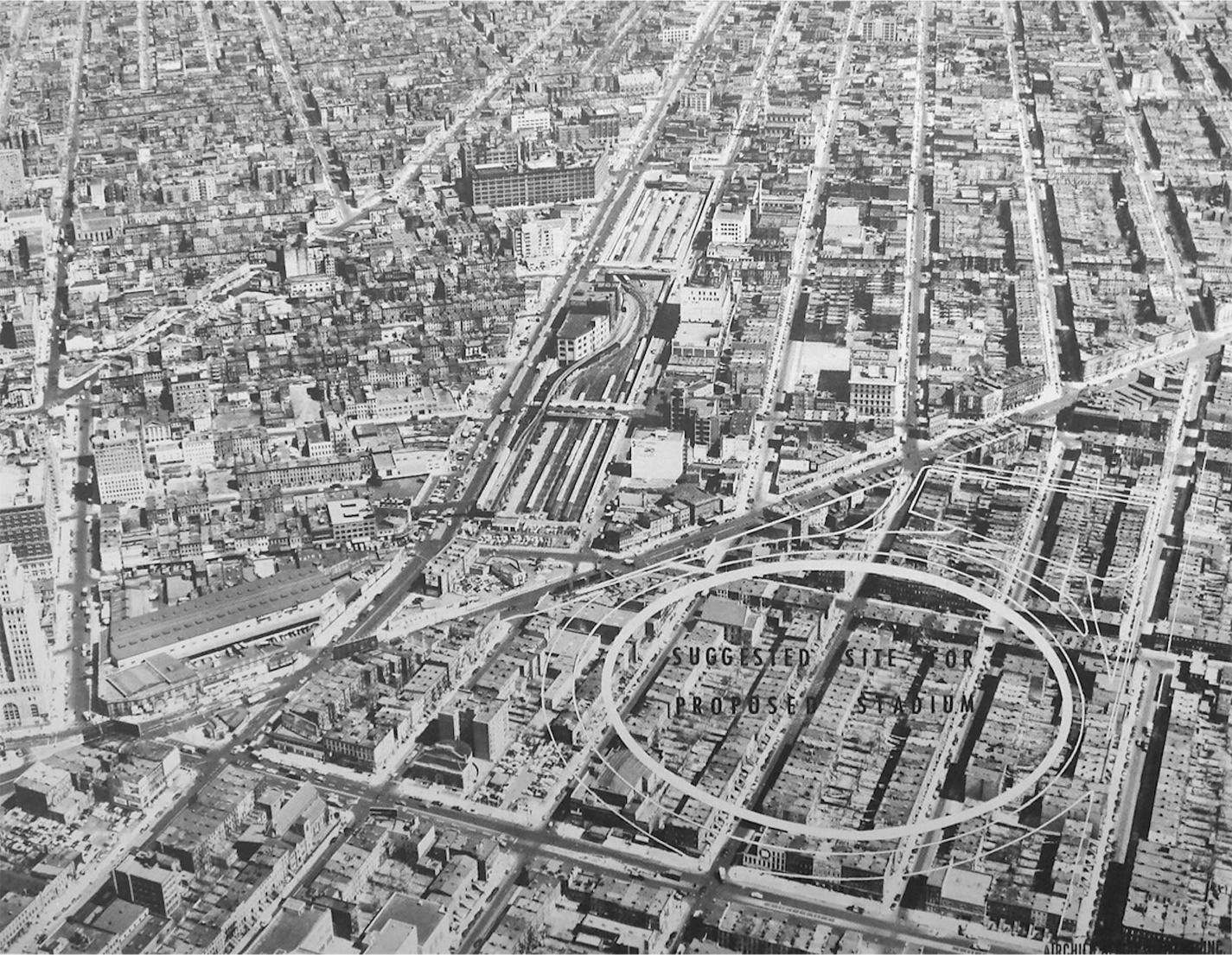

Like Friede’s fraudulent orb, a state-of-the-art Dodger stadium was destined to remain a figment of dreams and imagination. The real challenge was not the design of the new stadium, but where to put it and how to pay for it. With the Ebbets Field property too small and encumbered to support a modern stadium, O’Malley knew he needed a new site. But he needed help, for he lacked the money to both acquire the land and build a ballpark. Thus, in June 1953, he went to see the almighty Robert Moses, asking—hat in hand—whether urban renewal funds might be used to assemble land for a stadium at the junction of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues, on the site of the Long Island Rail Road’s aging depot at Hanson Place. Moses was no fan of professional sports, never much liked Brooklyn, and reviled O’Malley’s Tammany-Irish background. He resisted the Dodger owner’s overtures from the start. The ensuing battle of wills between the two men—both brilliant, both hardheaded, each long accustomed to getting his own way—has been written about extensively and need not be recounted here.20 Put simply, Moses refused to apply Title I slum clearance funds to build a stadium for a private ball club, arguing that eminent domain could not be used for anything other than improvements with a clear public purpose. Moses did agree, all the same, that O’Malley’s proposed Atlantic-Flatbush site was a good one. It had come into play when the antiquated meat market on Fort Greene Place, just behind the rail depot, was scheduled to close. Situated at a major crossroads, it was easily accessed by road, rail, and subway. It was here that Kleinsasser had sited his thesis stadium—the “Princeton bubble,” as Moses called it, “the idea of an ambitious graduate reporting to a rather wild professor.” At the final review, O’Malley had asked Kleinsasser—for the benefit of the reporters in the room—whether he had come across any better site “where the stadium could be logically be built.” As if rehearsed, the student responded, “No, sir; It’s the most magnificent site in the world.”21

Princeton architecture student Ted Kleinsasser (right) with (left to right) Emil Praeger, Walter O’Malley, and R. Buckminster Fuller, 1956. Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University.

O’Malley’s struggle to build a new ballpark in Brooklyn achieved a seeming major victory when an act to create a public benefit corporation—the Brooklyn Sports Center Authority—was signed into law by Governor Averell Harriman in April 1956. Drafted by attorney John P. McGrath and cosponsored by Brooklyn borough president John Cashmore and a somewhat skeptical Mayor Wagner, the bill was aimed at “constructing and operating a sports center . . . at a suitable location in an area bounded by DeKalb Avenue, Sterling Place, Bond Street and Vanderbilt Avenue”—a vast swath of vintage Brooklyn surrounding the rail depot that, in effect, extended the Brooklyn Civic Center urban renewal zone well to the south.22 Cashmore had, several months earlier, commissioned the ubiquitous Clarke and Rapuano to prepare a redevelopment plan for the area, to which was now tacked the immense task of siting a modern ballpark. Clarke’s report, completed in November 1956, made a number of recommendations—relocating the Long Island Rail Road depot, elevating Atlantic Avenue to create a grade-separated crossing at Flatbush, developing the air rights over the adjacent rail yards for housing. But where O’Malley and Kleinsasser had envisioned locating the ballpark on the depot site north of Atlantic Avenue, Clarke and Rapuano recommended instead a site to the south, just west of Flatbush Avenue, atop the Victorian-era homes of hundreds of working-class families.

In light of prevailing wisdom in urban planning and design, the Clarke and Rapuano proposal was a stunningly misguided piece of midcentury modernism, so wholly dismissive of traditional urbanism—architectural diversity, pedestrian scale, delightfully walkable streets—that even Robert Moses thought it was nuts. “The notion that we can declare a large area across Atlantic Avenue a slum is ridiculous,” he wrote to McGrath; “We would never get City Planning or federal approval. We would be murdered in Court and by public opinion.”23 Clarke, an otherwise brilliant planner, reasoned—evidently on Emil Praeger’s advice—that a stadium for fifty thousand people would never fit on the Long Island Rail Road parcel. He proposed placing it instead, with twin garages and a tangle of access roads, in the space bounded by Flatbush Avenue, Third Avenue, and Prospect Place—a sixty-acre wedge of Park Slope and Boerum Hill including some of the best brownstone blocks in all New York. Home plate would have been in the backyard of 105 Saint Mark’s Place, third base near 400 Bergen Street; the outfield wall would have run through LuLu’s for Baby and the kitchen of El Viejo Yayo on Fifth Avenue. Of course, in an era before Jane Jacobs nailed her thesis to the cathedral door, architects and planners saw little of value in “obsolete” neighborhoods like this, which Clarke himself described as “one of the more deteriorated sections” in downtown Brooklyn. All told, some eleven hundred buildings in the neighborhood would have been destroyed to make way for the colossal arena, its narrow streets blown out “to a minimum width of 100 feet” and the historic city grid obliterated “to create larger blocks better suited to the present day concept of residential redevelopment”—distended Corbusian superblocks, in other words, one of the great planning mistakes of the twentieth century.24

The ill-considered Clarke and Rapuano site for the new Dodger ball field on the edge of Park Slope. From Gilmore D. Clarke and Michael Rapuano, A Planning Study for the Area Bounded by Vanderbilt Avenue, DeKalb Avenue, Sterling Place and Bond Street in the Borough of Brooklyn (1956).

A week or so before the Clarke and Rapuano report was bundled off to the printers—on the morning of October 31, 1956—an icon of Brooklyn life passed into history. “While most of Brooklyn slept,” reported the Herald Tribune, “the last trolley cars on the last two remaining trolley lines in the borough made their last runs and quietly closed an era of public transportation.” It was a very bad sign for Brooklyn baseball; for, as we’ve seen, the fast electric streetcars—introduced in the 1890s—had given the many-named Brooklyn ball club its most famous appellation: the Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers. The beloved rattletraps had been disappearing from the streets of Gotham for years—and from cities across the country (New Rochelle’s last operating streetcar carried a sign that read “Streetcar Named Expire”). The last Manhattan trolleys—the Broadway-Kingsbridge and 125th Street crosstown lines—closed down in late June 1947. Brooklyn’s busy crosstown trolleys were pulled out of service in January 1951, replaced by the B61 bus. Those plying Smith Street (B75) and Seventh Avenue (B-67) were retired the following month, while service on Flatbush Avenue—the borough’s longest trolley line—ended on March 4 (replaced by the B-41). The new diesel vehicles, unpopular from the start, had all the magic and romance of a wet mop; “we have never been convinced,” the Times opined, “that the bus was a fair or completely beneficial exchange.” The October 1956 removal of Brooklyn’s last trolleys—from Church Avenue and McDonald Avenue—came, appropriately enough, just three weeks after the Yankees beat the Dodgers in the seventh (and final) World Series matchup between the two New York teams. Needless to say, the loss restored to Brooklyn its perennial underdog status.25

Ill-considered and ill-timed, the Clarke and Rapuano stadium proposal was fateful for another reason: it fractured the fragile consensus that was forming around the Long Island Rail Road site—one that, against all odds, O’Malley, Cashmore, and even Moses all agreed was the best location for a new ballpark. Now, with a respected planning firm—Moses’s own consultants on scores of projects—recommending a wholly different locale, the waters were newly muddied. Moses weighed in publicly on the whole “Dodger rhubarb” in a portentous July 1957 Sports Illustrated essay, complaining that professional baseball was “rapidly becoming our No. 1 domestic headache.” Claiming to be thoroughly bewildered by the stadium shenanigans—“I am no diagnostician,” he professed, “merely a builder of parks and public works”—Moses blamed the mess on the “assorted tribal doctors, medicine and confidence men, shills, barkers, swamis and self-anointed pundits” who offered nothing but quack remedies. He described O’Malley’s appeal as a sob story full of veiled threats and “embroidered . . . with shamrocks, harps and wolfhounds,” and feigned fresh indignation over the proposal that eminent domain be used to assemble land for the ballpark. “From the point of view of constitutionality,” he wrote, “Walter honestly believes that he in himself constitutes a public purpose.” Moses reserved special vitriol for infidels Clarke and Rapuano. “Instead of directing various city agencies to concentrate on a careful analysis of this site,” he crabbed, “a firm of planning consultants turned to an alternative site across Atlantic Avenue which included expensive built-up property and was by no stretch of the imagination a slum.” The move “further bedeviled and confused an already difficult problem”—in large measure, of course, because it had infuriated New York’s omnipotent master of public works.26

One of Brooklyn’s last working trolleys is loaded on a flatbed truck, January 1953. The borough’s streetcar system was once the most extensive in North America. This car, No. 8111, served Ocean Avenue and is preserved today at the Shore Line Trolley Museum in East Haven, Connecticut. Photograph by Jules Geller. Public Library, Brooklyn Collection.

In the end, of course, O’Malley left Brooklyn, taking his ball club to that sunny national suburb, Southern California. The Dodgers played their last game at Ebbets Field on September 24, 1957. The team was gone one month later. “If somebody had asked me 10 years ago, ‘Which do you think is the most likely to move—the Brooklyn Bridge or the Brooklyn Dodgers,’” quipped Leo Durocher, “I’d have picked the Bridge.” The ballpark was sold to a local developer, Marvin Kratter, who pulled it down for a housing project and spent the rest of his life in repentance. O’Malley became, unfairly, the most hated man in Brooklyn; “Hitler, Stalin and Walter O’Malley,” sang the chorus. That changed only with Robert Caro’s 1974 publication of The Power Broker, which revealed Moses to be the real demon in the Dodger tale. But blame must also be placed, perhaps first, at the feet of Dodger fans themselves. Long “more vociferous than numerous,” these were the very souls fleeing Brooklyn in droves after the war—and who would, oblivious to their own role—weep tears for decades for the “beloved Bums” and the Brooklyn of their youth. Ultimately, what propelled the Dodgers out of town was neither O’Malley’s duplicity nor Moses’s stubbornness, but the loss of their fans. “The dominant issue,” writes McCue, “was attendance. Despite the legend of legions of vocal, supportive, and, above all, devoted Brooklyn fans, the evidence is that not enough of them were buying tickets to Ebbets Field at the rate the legend would have predicted.” Ticket sales to Dodger ballgames mirrored Brooklyn’s falling population. As we have seen, between 1950 and 1955 alone some fifty thousand Brooklyn residents left town, most from the same white working- and middle-class demographic that formed the core of Dodger fandom. While Major League Baseball nationwide underwent a 22 percent decline in game attendance between 1947 and 1956, the Dodgers numbers dropped by a whopping 33 percent in that period—a difference of some 800,000 attendees. “We have given the fans the finest baseball possible in the last nine years,” O’Malley grumbled, “and still our attendance declines.” Indeed, not even that most elusive of dreams—a Dodger world championship, captured at long last in 1955—would stem the inexorable tide of flight.27

A wheelchair-bound Roy Campanella bids farewell to Ebbets Field, February 1960, shortly before the stadium was razed. Bruce Bennett / Getty Images.

The clouds of change above postwar Brooklyn were nowhere more highly charged than over that other landscape of summer delights, Coney Island. There, racial lines were quite literally drawn in the sand that ultimately spelled the doom of that American Tivoli, Steeplechase Park, Brooklyn’s oldest and most venerated playground. Though the great weekend crowds of the Depression and war years were long gone, Coney Island did well enough all through the 1950s—despite the steady loss of much of its patron base to the backyards of suburban Long Island and resplendent state parks like Jones Beach. To some extent, the losses were offset by a new source of patrons; arriving African American, Puerto Rican, and West Indian residents were just as excited as whites about Coney Island’s famous beach and amusements. And if the expanding regional highway system spirited many old patrons off to the suburbs, it also brought new ones from far away. By the late 1940s, Steeplechase had become an especially popular destination for African Americans from Maryland, Washington, and northern Virginia, where amusement parks were either officially segregated or effectively so. Black church and civic groups would charter buses for day trips to Steeplechase Park, which they knew to be safe not only from bad weather (its great pavilion assured that a long bus trip would not be a wash), but from the rougher aspects of Coney Island. In 1945, one ride operator estimated that there were “nine Negroes to every white” at Coney Island on the Fourth of July, “and all heavy spenders.” The profligacy stereotype would be invoked over and over by amusement operators—the very beneficiaries of the alleged extravagance. “Labor Day brought many excursions via busses, mainly from out of town,” reported the Billboard in 1949, “with the percentage largely in favor of Negro customers”—visitors “gladly welcomed . . . because of their liberal spending.” Blacks were drawn, too, by the fact that many of their people worked at the park. African Americans had long been employed as laborers in Coney Island, but Steeplechase was the first to put them in frontline jobs dealing with the public. The first were hired in 1943, many as “Red Coats”—the park’s uniformed workers who operated rides, punched tickets, and worked as “platform men” assuring patron safety on rides. As World War II got under way, many more African Americans were brought on to replace workers serving in the military. By the late 1940s, Steeplechase was the largest and most visible employer of African Americans in Coney Island.28

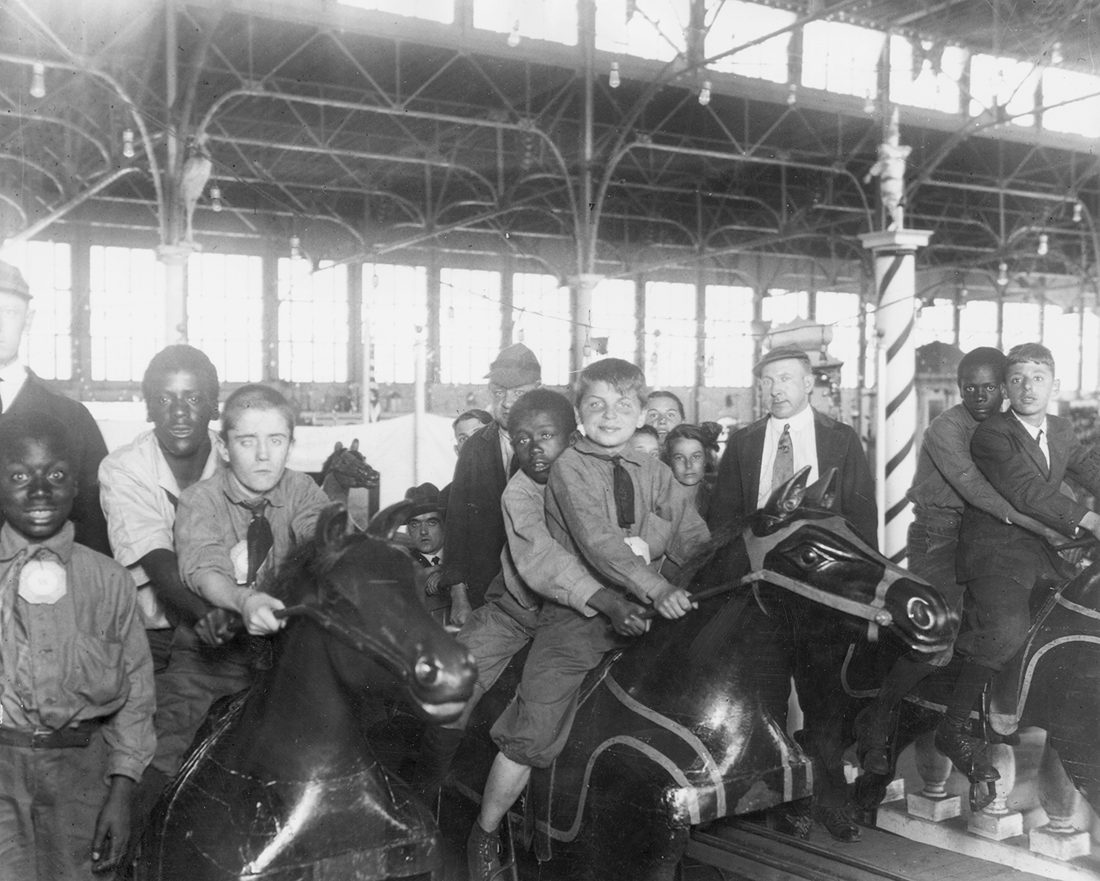

In fact, blacks had been part of Coney Island life for well over a century by this time. A hardscrabble community had formed as early as the 1830s in the salt meadows along Coney Island Creek—the “old negro settlement,” as it was known, which survived municipal dumping only to be wiped out by a fire in October 1909. As we saw in chapter 5, a more substantial black community evolved in nearby Gravesend and Sheepshead Bay as thoroughbred racing was established there in the 1880s. By the 1920s, in wake of the first Great Migration, African Americans from Harlem began visiting Coney Island in steadily rising numbers. Many first came on church outings, like the one to Steeplechase Park led by the Progressive Mission on Lorimer Street in September 1923—an event noted in the Chicago Defender. Black civic organizations also brought large groups down to the island. In 1938 the Harlem-based Amsterdam News, New York’s leading black daily, led a big outing to Luna Park for three hundred of its paper boys. But though their coin was welcome, African Americans were often treated with resentment and hostility at Coney Island—where racial prejudice was as much a part of daily life as the sand and sea. It didn’t help that blacks were often brought in by employment agencies to break strikes by Coney Island’s hotel and restaurant workers (whose unions barred blacks). The crass amusements of the midway were a special chamber of racial humiliations. Among the most shameful was a game eventually outlawed by the state legislature during World War I. It featured a “negro who will put his head through a hole in a canvas,” explained the New-York Tribune in 1911, “that it may become a target for all who will gamble on hitting it with a baseball.” Though the human target was able to maneuver somewhat to avoid the ball, “the general effect upon the boys and girls who see it,” observed the Tribune, was to make “the sport . . . alright so long as it is a negro that is hit.” Bam Boula, an African native, toured with an animal troupe until 1910. A popular freak-show attraction at the Palace of Wonders in the late 1920s was a caged “wild man,” actually a young African American novelist named Leroy Flynn, who forced himself to endure a daily barrage of racist catcalls to pay the rent.29

Boys, black and white, prepare for a race on the namesake horse coaster at Steeplechase Park, 1910. Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

Though Steeplechase Park prided itself on being a moral octave above the rest of Coney Island, plenty of midway riffraff got through the gates. Shortly after opening day in May 1912, a Steeplechase porter named Aaron Nelson was arrested for lashing out at a group of white men who had been tormenting him. “Maddened by the taunts and insults of the men, Nelson suddenly whipped a knife from his pocket and began to slash out blindly,” injuring two and landing himself in prison on charges of felonious assault. Nor was management always innocent. “Race discrimination at George C. Tilyou’s famous Steeplechase,” reported the Amsterdam News in 1927, “continues unabated. Within the last several years numerous complaints have been lodged against this popular amusement enterprise.” In July 1920 a Steeplechase bathhouse worker named Jennie Newton refused to sell a ticket to George E. Wibecan, Jr., a nineteen-year-old Brooklyn electrician of mixed African and Danish heritage. Prior to completion of the boardwalk in 1923, nearly every inch of beachfront at Coney Island was private. Access was via bathhouses, where visitors wishing to swim were forced to pay a fee. But Wibecan was the wrong person to cross; he had civil rights in his blood and refused to go quietly. His grandfather was a West Indian immigrant who survived the Draft Riots by hiding in a rowboat at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. His father, a former “ruler” of the Colored Elks of the World and president of the Crispus Attucks Community Council, was a prominent Republican Party leader. Wibecan, Sr., had brought Frederick Douglass to Brooklyn in 1892 and organized the purchase of Harry H. Roseland’s painting of the infamous Beecher slave-girl auction—“Pinky”—as a gift of gratitude to Plymouth Church in 1928 (where it still hangs). The younger Wibecan reported the bathhouse matter to the police and then sued Steeplechase Park. Newton was promptly arrested “on a charge of discrimination”—testament to the respect the Wibecan name commanded even in the white community. Though the case was dismissed in court, it galvanized Wibecan’s passion for racial justice; he later became active with the NAACP and fought housing discrimination as chair of the Montclair Civil Rights Commission.30

A young African American couple and their child on a hot day at Steeplechase Park, July 1939. Andrew Herman for Federal Art Project / Museum of the City of New York. 43.131.5.49.

The Wibecan incident was just one of many, few of which ever made the news. A story that did took place in the middle of a heat wave in July 1927. Two African American teenagers—Ernest Huggins and his sister Josephine, a student at the Yale School of Music—and an older family friend named Fannie Potter had purchased the standard combination ticket to Steeplechase Park before attempting to rent “carnival suits”—overalls made of coarse fabric meant to protect a patron’s clothes from dirt and grease on the rides. The suit vendor refused to serve the trio. Pressed, he sent them to speak to George Tilyou, Jr., son of the founder. Tilyou coolly informed them that a $25 deposit would be required for each suit, not the twenty-five-cent fee charged white patrons. Outraged, Potter returned a week later with a reporter from the Amsterdam News; she again sought to rent a carnival suit and was again told by Tilyou that she must first pay the inflated “colored” fee. (Decades later, coincidentally, Josephine Huggins would teach music at the Harry Conte School in New Haven, centerpiece of the Wooster Square renewal project and brainchild of Cy Sargent, father of the Brooklyn Linear City). Fortunately, blatant acts of discrimination like this became infrequent as more and more blacks flocked to Coney Island after the Depression. By the 1940s, Jim Crow had effectively withdrawn to a handful of dark recesses—all spaces of public intimacy where strangers of both sexes were put into close contact with one another.31

Integrating such holdouts—swimming pools, dance halls, bathhouses—was a struggle that unfolded in cities across the United States as the civil rights movement got under way. In Biloxi, Mississippi, a riot ensued when protesters staged a “wade-in” on a segregated beach in 1960, prompting the Justice Department to bring suit against the city (federal funds had been used to create the beachfront). Wedgewood Village amusement park in Oklahoma City was integrated in June 1963 after a large demonstration in which fifty people were arrested. Owner Maurice Woods relented only after receiving repeated telephone threats “to kill him and members of his family and to blow up the park.” But attendance plunged soon after, convincing Woods to try a harebrained “Black Thursday” plan—integrating the park that one day and restricting admission “only to non-Negro customers” the rest of the week. An incensed NAACP rejected these “spoon-fed days at Wedgewood” and promised to organize new rallies. Demonstrations were staged at Chain of Rocks park in suburban St. Louis and Holiday Hill near Ferguson, Missouri, where blacks were admitted only as part of mixed school groups. In New Orleans, African American parents sued to desegregate municipal playgrounds and recreation centers; the city rejected their pleas, arguing that blacks and whites “co-mingled in large numbers in public parks has definite dangers to the peace and tranquility of the State.” For years, the owners of Gwynn Oak Park in Baltimore deflected requests to integrate from the NAACP, the Congress of Racial Equality, and the Maryland Commission on Interracial Problems and Relations. Matters came to a head on the Fourth of July 1963, when a huge rally at the gates was ordered to disperse; nearly three hundred people were arrested, including “clergymen of all three major faiths” (Episcopal priest Daisuke Kitagawa and Bishop Daniel Corrigan were among them). Owner Arthur B. Price defended the white-only policy in real estate terms, claiming that “an impulsive switch would shake values.” “I don’t condone second-class citizenship,” he retorted; “but the road to first-class citizenship is not downhill on a Roller Coaster.” The work of integrating erstwhile places of joy was often wretchedly comic: in June 1964 a group of fifty civil rights demonstrators marched into the surf on a segregated public beach in St. Augustine, Florida, an equal number of starchily uniformed state troopers wading in at their heels.32

Ugly fears of miscegenation made swimming pools among last redoubts of segregation throughout the United States. As Jeff Wiltse has written in Contested Waters, “Although the rationale remained mostly unspoken, northern whites in general objected to black men having the opportunity to interact with white women at such intimate and erotic public spaces. They feared that black men would act upon their supposedly untamed sexual desire for white women by touching them in the water and assaulting them with romantic advances.” White resistance was often violent. When a large group of African American men attempted to swim in Pittsburgh’s immense new Highland Park pool in August 1931, they were hounded out of the water. “Each Negro who entered,” reported the Post-Gazette, “was immediately surrounded by whites and slugged or held beneath the water until he gave up.” After passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, operators outfoxed the new law’s “public accommodations” clause by becoming members-only clubs. The owners of Alward Lake Resort in suburban Lansing, Michigan, hauled into court for refusing admission to a group of African American college students, sidestepped the matter by immediately reorganizing as a private club. So did Lakeland Park east of Memphis, which privatized just days after the act was signed into law by President Johnson. Fees were low at Lakeland, but memberships could be purchased only “in person at the park.” “You can’t buy by mail,” related manager Louis M. Garner, for obvious reasons. Fontaine Ferry Park in Louisville, Kentucky, was successfully integrated, except for the pool, which was hurriedly leased to separate management to be operated as a members-only facility. Many pools were simply closed to resist integration. The city manager of Little Rock, Arkansas, preemptively shut the city’s two public pools—one white, one “colored”—days before the landmark bill passed the Senate. In Atlanta, residents demanded that the recently integrated pool at Candler Park be shut down, fears of “race mixing” thus taking precedence over the summer fun of their own children (a case of throwing the baby out with the bathwater if ever there was one). Not coincidentally, it was in this era that backyard swimming pools soared in popularity. Only about 2,500 American households owned an in-ground home swimming pool in 1950. The number hit 26,000 by the end of 1955, and 375,000 a decade after that. By 1970 there were some 800,000 residential pools in the United States, a figure that would continue to soar in coming years. “The proliferation of residential swimming pools,” writes Wiltse, “represented not simply an abandonment of public space but a profound retreat from public life,” accelerating the atomization of American society by reducing opportunities to interact with people of different backgrounds.33

At Coney Island, the struggle to integrate dance halls, pools, and other spaces of public intimacy began early. Luna Park was the first target of coordinated action. In July 1940 the Brooklyn Council of the National Negro Congress launched a “determined drive against the alleged discrimination of Negroes” at Luna, where—as the Amsterdam News reported—blacks “were admitted to other attractions . . . but were refused admittance to the dance hall.” Vowing to fight “any and all discriminatory practices on the island,” the committee—led by Frank D. Griffin and Malcolm G. Martin—organized a mass meeting at West Thirtieth Street and Mermaid Avenue. Samuel A. Neuberger, a prominent labor lawyer, then filed suit against Luna Park. The council went after Luna’s pool the following summer, charging that management’s refusal to admit a group of African American boys was a “Hitler-like action” that would result in another lawsuit. These actions were generally successful at Coney; ride and amusement operators dreaded negative coverage in the city’s dozen-odd dailies and quickly backed down. After the war, with so many blacks working at Steeplechase and other attractions, truly segregated spaces became scarce. Steeplechase was soon booking acts specifically aimed at black audiences. Fred Sindell’s Cavalcade of Variety often played to packed crowds, with a show “catering for the most part to the Negro element.” Racial attitudes had so softened that even poet Langston Hughes could wax forth on Coney Island’s vibrant diversity. There, as summer thickened and Gotham sweltered, the beaches grew “crowded with bathers of all nationalities and sizes and shapes with no color line between them,” the hot sun “doing its best to make everyone darker.” Hughes saw hope even in the loutish midway: “A side show has a colored snake charmer,” he wrote in 1947; “the strong man is white as is the fire-eater, the turtle-girl is colored, but a mule-faced boy is white. Democracy is all-inclusive at Coney Island.”34

There was one last holdout of segregation in Coney island, and it was at that paragon of middle-class respectability, Steeplechase. There, the park’s famous swimming pool had become a kind of sanctum sanctorum after World War II—a last redoubt against the churn of societal change. Built on the very site of the Friede Globe Tower, it was the largest saltwater pool in North America, as long as a city block is wide and filled with 160,000 gallons of seawater. It was flanked on either side by simple loggias topped with bleachers (women were prohibited from the west bleacher, as it afforded a clear view of the men’s showers and changing rooms). At the head of the pool was an ornate tower modeled loosely on those of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Originally meant for the newly opened boardwalk, the tower (which also concealed a water tank) was designed by Michael Marlo, an Italian immigrant architect who did extensive work over the years at Steeplechase. The pool was open to daily bathing prior to World War II—admission was fifty cents—but in March 1946 the Tilyou family launched a “season bathing only” policy. Bathers were now required to rent, as individuals or a family, a locker or tiny bathhouse each spring to use the pool. It is not clear whether this was meant to exclude the many blacks who had begun flocking to the park after the war, or was simply a means of raising cash to paint and prep the park well in advance of opening day. The units were not cheap: the 1947 rate for a bathhouse for a couple with two children was $72—nearly $800 in today’s dollars. It may also have been a way of regulating behavior at the pool; for troublesome or rowdy guests could be threatened with losing their lease. Whatever the motivation, season bathing was private-club membership by another name; it effectively segregated the pool. Though African Americans can clearly be seen enjoying Steeplechase rides in Pathé newsreels from the 1920s, in footage from the pool’s annual Modern Venus bathing-beauty competition in the 1940s and 1950s—and in Reginald Marsh’s many photographs of the event at the Museum of the City of New York—not a single black person can be seen among either contestants or the large crowds of onlookers.35

Patrons on an updated version of Sam Friede’s old airship tower ride at Steeplechase Park, c. 1945. The great glass-and-steel façade of the Pavilion of Fun, target of Fred Trump’s bikini-clad vandals, is in back. Hulton Archive / Getty Images.

The Tilyous and their legendary park manager, James J. Onorato—a man Walt Disney spent a week with and tried to recruit before he launched Disneyland—were untroubled about the implications of the members-only policy, at least at first. Few blacks seemed interested in the pool, which—compared to the jubilant beach scene—appeared stuffy and unwelcoming and was not included on the park’s famous combination ticket. It was also filled with the same seawater as the surf, where one could splash about all day for free. The Tilyous also held the view, abhorrent today but common at the time, that blacks did not like to swim, especially in frigid saltwater (the pool was emptied and refilled on Tuesdays and Thursdays, so it never had a chance to warm up). Why stir up trouble with the season bathers, they reasoned, when blacks themselves showed little or no interest in the pool? Of course, it mattered not a whit whether or not African Americans wanted to use the pool: that they were prohibited from doing so was all. As the struggle for civil rights came together in the late 1950s, word began circulating that blacks were being barred from the Steeplechase pool. Comity and decorum were declining generally at the park, and the pool crowd was becoming especially rowdy. Season bathers began to crow about the pool’s racial exclusivity, infuriating Onorato and the Tilyou family. Onorato was becoming nervous; “I told the Tilyous,” he recounted later, “that we were skating on thin ice with our white only policy.” On July 9, 1959, following a tip, Bill Leonard of WCBS did a story about “color discrimination” at the pool on his popular evening radio program. Suddenly the whole city knew that Jim Crow was summering at Steeplechase. It was a season of growing scrutiny of discriminatory practices in the city. The very day Leonard’s piece aired, the New York Times ran a front-page story on how the elite West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills excluded blacks and Jews from membership, refusing to allow even Nobel laureate and UN official Ralph Bunche and his son to join.36

In the early spring of 1964, with the civil rights bill moving through the Senate, the Tilyous decided to preempt a very public integration battle by shutting down the Steeplechase pool. Duly notified on March 15, the season bathers—an increasingly rancorous and insubordinate group—were outraged; some threatened violence. The flush of cash in spring from membership rental fees would surely be missed, but even that hardly compensated for the headaches the pool and its entitled patrons were causing—especially now that the city health department was demanding that a costly new filtration system be installed. The great tank was dutifully filled as before, deck and railings painted and prepped, even the Adirondack chairs were set out—all to keep up appearances; the gates remained locked. The stilled, silent water was an omen in a season of bad signs. Just five days after Steeplechase opened for the season on May 2, the last surviving son of George C. Tilyou—Frank S. Tilyou, born at his father’s park in 1908 as the Pavilion of Fun neared completion—died in Phoenix after a brief illness. Frank played an active role in park management all his life and changed the Brooklyn skyline by bringing the Life Savers parachute jump to the boardwalk from the 1939 World’s Fair. Shuttling between his home at 35 Prospect Park West and the Flying T Ranch in Scottsdale, he was the linchpin that kept the querulous Tilyou heirs in line. His death threw the family into disarray. In a letter the very next day, May 8, 1964, Jimmy Onorato related to his son that negotiations were already under way to sell the Steeplechase property “for an apartment project.” The bombshell news, that the economic rug was about to be pulled out from under Coney Island, was kept secret for months. Meanwhile, attendance boomed. On Sunday, May 24, with the mercury pegging ninety-one degrees, an estimated 900,000 people flocked to Coney Island. It was the largest crowd since the end of the war.37

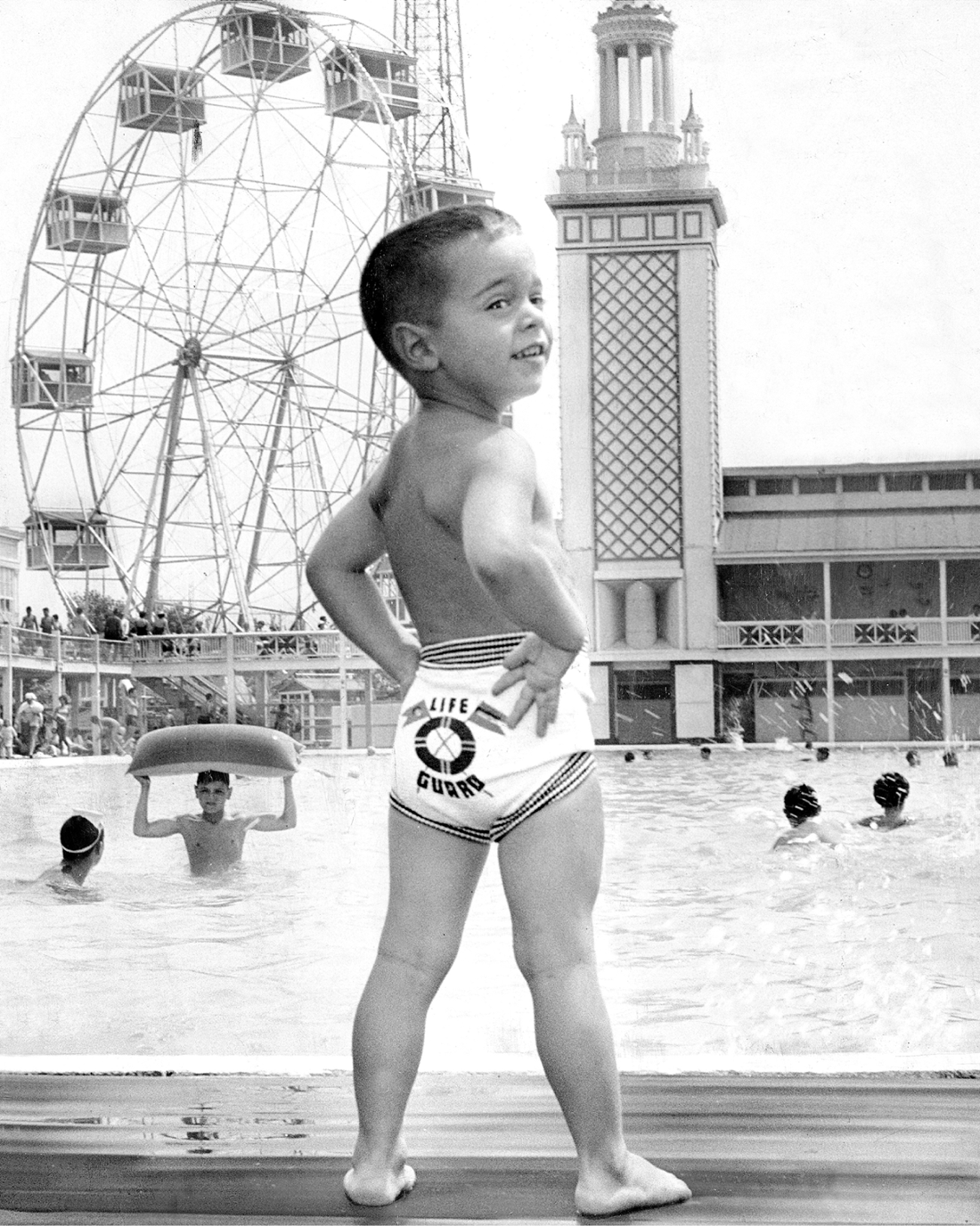

A precocious little boy surveys the troublesome Steeplechase pool, July 1960. New York Daily News Archive / Getty Images.

But the pot, long simmering, was about to boil over. The following Saturday—Memorial Day weekend—saw racial unrest throughout the city. “Very bad disorderly crowd,” the laconic Onorato confided to his diary on May 30; “hoodlums—trouble in City & riot in Coney Island—bad for business.”38 Gangs of teenagers terrorized passengers on subways and the Staten Island Ferry. A group of twenty black youths that boarded the D train at Stillwell Avenue “beat and robbed white passengers, and smashed windows and light bulbs.” At Kings Highway, the motorman stopped the train and called for help. A boy attempting to leave the train was struck on the head with a bottle and knocked unconscious. In the adjoining car a man was similarly assaulted. “He tried to get out when the train doors opened,” his wife recounted to a Times reporter, “but they dragged him back in and started beating him up.” Echoing the Kitty Genovese case just two months earlier, she added that “fellow passengers refused to help him while he was being attacked.” The marauders then fled the station, breaking shop windows and pillaging stores on Kings Highway. Residents “poured out into the street and shouted racial epithets,” the Times reported. The police ultimately arrested a dozen youths, while restraining angry locals “from attacking the teenagers.”39 By mid-July, the whole city was seething with racial tension. Six nights of violence in Harlem and Bedford-Stuyvesant were set off by the July 16 police killing of James Powell. People began avoiding crowded public places. Attendance at Steeplechase plunged. Profits had been declining for years as costs spiraled and more and more people fled to the suburbs of Long Island. But as Labor Day neared, it became clear that the 1964 season would go down as the very worst for Steeplechase in the postwar period. “Violence,” observed Onorato, “cut the attendance in half.” At a September 24 meeting, Marie Tilyou and the family decided not to open Steeplechase again. It was a day everyone knew was coming. When Onorato closed the park for the season the previous Sunday, he had done so with all the solemnity of a state funeral. Michael Onorato, then a professor at Canisius College, beheld the final moments from afar. “My father placed a long-distance call to me,” he recalled, “from an extension phone located at the Eldorado carousel.”

At 7:35 p.m. the closing bell, which was a rescued locomotive bell, signaled the Park’s final closing. Then the public address system played “Auf Wiedersehen,” “There’s No Business Like Show Business,” and then “Auld Lang Syne.” As the music finished, the bell began to toll slowly for each year of the Park’s existence.

With each stroke, the electricians shut down “tier after tier of lights throughout the Park.” All became dark and quiet. And then, with Broadway flourish, Onorato had the men throw all the big paddle switches back on for a brief moment, setting the grounds aglow in a last blaze of light before night fell for good. Steeplechase Park, anchor of a playground that touched a million lives and transformed American culture, lay in a darkness broken only by the glow of emergency lights.40

Sic transit ludicrum mundi. Fred C. Trump surveys the emptied shell of George C. Tilyou’s Pavilion of Fun, what Reginald Marsh called “the last and greatest example of Victorian architecture in the United States.” Trump razed the beloved landmark just months after this photo was taken in February 1966, an act of vandalism as tragically shortsighted as the destruction of Pennsylvania Station the year before. Photo by Leroy Jakob. New York Daily News Archive / Getty Images.