Shahid Javed Burki and Adnan Naseemullah

Pakistan’s economy—which has been struggling with fiscal deficits, high inflation, declining dollar reserves, and the drying up of foreign direct or portfolio investment that could finance current account deficits—continues to depend on external support.1 In September 2013, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) approved a three-year conditional extended facility loan of $6.6 billion to Islamabad. The IMF program was supplemented in March 2014 by a $1.5 billion loan from Saudi Arabia—not to say anything about the resilient American aid (see chapter 8).

Economic activity has been affected in 2013 by an acute power crisis, including widespread blackouts throughout the country that continued into the tenure of the Pakistan Muslim League—Nawaz (PML-N) government. The year 2014 yielded some better news in terms of growth, but the underlying structural weaknesses of an externally dependent economy remained. For Pakistan to return to a sustainable path of growth and development, after nearly a decade of insurgent violence, political instability, and growing international isolation, both the lack of internal consensus and an overreliance on foreign largesse needs to be addressed.

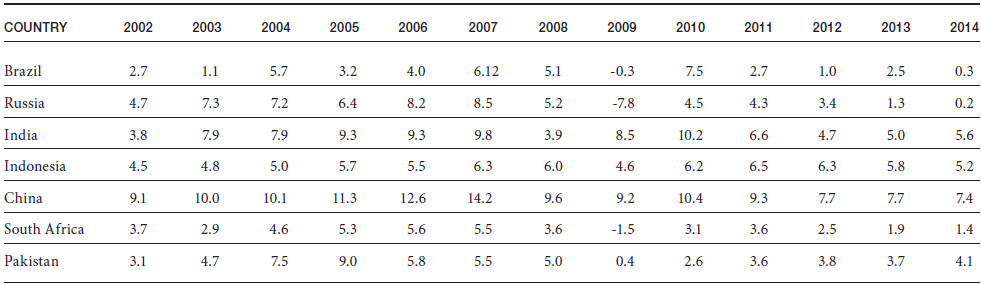

Pakistan is now the sick man of South Asia. If current trends continue, the country may well become the most stagnant in the subcontinent; Bangladesh’s growth rate is now twice that of Pakistan (table 6.1).

This chapter argues that powerful proprietary groups in Pakistan, from the salariat to the landed elite to the military, have been unwilling or unable to come to agreement on basic political and economic accommodations that would limit their claim to the national fisc and allow for investment-enabling expenditure and space for domestic growth and development. As a result, Pakistan has over several decades been reliant on external sources of economic support to fund domestic fiscal and current account deficits, particularly in exchange for Pakistan’s commitments as a U.S. ally in the Cold War and the war on terror. Such foreign assistance, never guaranteed at the best of times, seems further in doubt given continued economic stagnation in the West and the decreasing relevance of Pakistan to international security, as international intervention in Afghanistan draws to a close.

TABLE 6.1 COMPARATIVE GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT GROWTH RATES IN SOUTH ASIA, CONSTANT PRICES (PERCENT)

| COUNTRY |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2013 |

2014 (P) |

2015 (P) |

| India |

10.2 |

6.6 |

4.7 |

5.0 |

5.6 |

6.4 |

| Bangladesh |

6.0 |

6.5 |

6.2 |

6.1 |

6.2 |

6.4 |

| Sri Lanka |

8.0 |

8.2 |

6.3 |

7.3 |

7.0 |

6.5 |

| Pakistan |

2.6 |

3.6 |

3.8 |

3.7 |

4.1 |

4.3 |

NOTE: P = PROJECTED.

PAKISTAN’S POTENTIAL IN COMPARATIVE PERSPECTIVE

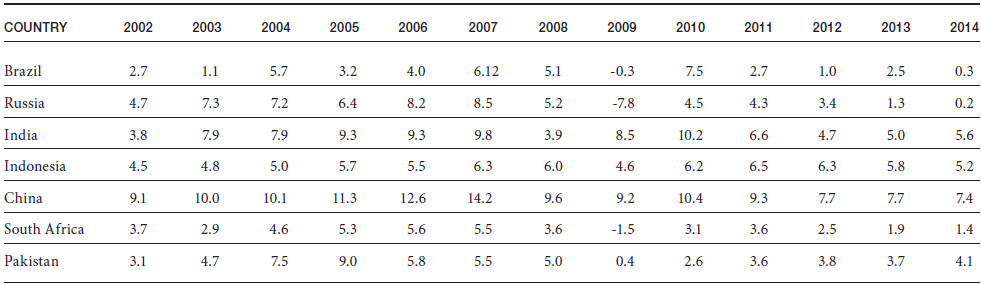

Pakistan could certainly be more successful and more economically self-reliant. It is not hugely different, in terms of its endowments, from the “BRIC” countries of Brazil, Russia, India, and China and emergent economies like Indonesia and South Africa (table 6.2).

What distinguishes the BRIC countries from the rest of the developing world is their size (population and gross domestic product (GDP), their dominance in the region to which they belong, their recent rates of economic growth, and their economic potential. Pakistan meets three of these four criteria. It has now a large population, approaching 200 million, less than that of China, India, Indonesia, and Brazil but more than that of Russia and South Africa.

It is furthermore located in the region that has high growth potential. Several countries in its neighborhood have vast energy resources. Some, such as Afghanistan, have recently discovered large mineral deposits, which may well extend into the Pakistani province of Baluchistan. Pakistan could become a key node of cross-country commerce between India to the east and southeast, China to the northeast, the Middle East in the west, and Afghanistan and the Central Asian republics in the north. Its rich human resource base should provide what the demographers call the “window of opportunity” that will remain open for a period longer than that for the BRIC countries.

TABLE 6.2 BRIC AND PAKISTAN GROSS DOMESTIC PRODUCT ANNUAL GROWTH RATE, CONSTANT PRICES (PERCENT)

NOTE: BRIC = BRAZIL, RUSSIA, INDIA, AND CHINA.

SOURCE: WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS.

Its diaspora, estimated at 4 percent of the national population, is located in several parts of the world; remittances from emigrants are a key source of capital inflows. Remittances have slowly increased the stock of foreign currency reserves in recent months, even as other sources of foreign finance have dried up. Diaspora populations are also untapped sources of other kinds of capital. They could potentially provide valuable managerial, financial, and other skills for reforming and transforming the economy.

The country has a rich agricultural sector supported by one of the world’s largest irrigation systems, developed initially under colonial rule but expanded later by Pakistani investment, as well as the successful implementation of Green Revolution technologies. Agricultural production of cash crops such as cotton as well as a range of foodstuffs serves to provide for international trade in these commodities, to spur the industrial production of textiles and processed foods, and to stabilize domestic food supplies. These are some of the endowments that could be counted on to produce a better economic future. Compared with the BRIC countries, the only area where Pakistan has performed poorly is in terms of the rate of economic growth in recent years. This was not always the case. In fact, the country has experienced a number of growth spurts over the last half century. In the 1960s, the 1980s, and the early 2000s, the rate of GDP growth reached between 6 and 7 percent a year for extended periods.

These high-growth periods have meant respectable increases in per capita incomes. One consequence of this has been the emergence of a sizeable middle class, numbering between forty and fifty million people. This is large enough to give the economy a sustained push toward a higher rate of growth and economic modernization.

Why has the country done poorly compared with its potential? It is important to emphasize the link between economic development and the political environment in explaining Pakistan’s roller coaster economic performance.2 Had the country known greater and more consistent political stability, it would have arguably had a more consistent record of economic performance. The country has tried several different models of political governance and economic management. The military ruled for 33 years out of the 65 years of postindependence Pakistan. Moreover, during some periods of democratic rule, the military has maintained an influence on policymaking. This constant back-and-forth between military and civilian rule has adversely affected economic development. Certain periods of political instability produced uncertainty about the country’s economic future.

Economies seldom do well in an environment marked by political uncertainty, but this uncertainty is a manifestation of something deeper: the inability of political groups in Pakistan to reach agreement on the allocation of rents and resources between groups, within a constitutional framework that regulates the alternation and distribution of power based on electoral success and that prevents the exercise of power by the military. As a result, political parties march on the capital with disheartening frequency, the military often intervenes in civilian politics, and individual political leaders are often as interested in looting the state as formulating and implementing growth-enhancing policy. The capacity for increased public and private (foreign and domestic) investment in value-added activities is dependent on a stable environment in which no one group is able to threaten public order in order to acquire a greater piece of the pie through contentious means. Yet Pakistan’s politics leave us with little indication that such an environment, and the political compact that would allow for it, is forthcoming. The lack of sustained domestic resource mobilization and investment means that Pakistan’s economy relies on foreign inflows, in terms of official aid, emergency loans, and remittances to keep the economy afloat while maintaining its external obligations. Such domestic contention and such external reliance have truncated Pakistan’s potential as an economic power.

THE FOUNDATIONS OF PAKISTAN’S POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS, 1947–2008

The civilian rule for the first eleven years after independence was in a constitutional vacuum. Unlike India, Pakistan’s sister state, which constructed an enduring constitutional framework within four years of gaining independence, Pakistan struggled for almost a decade before agreeing on a basic framework for governance. The 1956 constitution gave the country a parliamentary form of government and a federal structure. Yet this constitution survived for only six years and was never put to the electoral test. The first general election was scheduled for late 1958, but in October 1958, General Mohammad Ayub Khan declared martial law. The military government abrogated the constitution and promised a new political order.

Ayub Khan introduced a new system of governance under the constitution adopted in 1962. This was a highly centralized presidential system, with members of the national and provincial assemblies indirectly elected by an electoral college of 80,000 “basic democrats,” themselves either elected from the population or appointed by the state. This created considerable distance between those who governed over those they ruled. Ayub Khan’s fall came when some of the citizens who felt that they had not benefited from the high rates growth of the period came out on the streets. The army stepped in to restore public peace.3 In 1969, General Yahya Khan, the army chief of staff, abrogated the 1962 constitution and removed Ayub Khan from office.

The new military president governed under the “Legal Framework Order” (LFO). The LFO provided the framework for holding the country’s first general elections based on adult franchise, in December 1970. The seats in the National Assembly were distributed on the basis of population, which meant that East Pakistan (today’s Bangladesh) received a larger share than West Pakistan (today’s Pakistan), a departure from the principle of “parity” between the two wings that was the basis of the two previous constitutions. The elections produced a majority for the Awami League, a party based almost entirely in East Pakistan. Its leader, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, had campaigned on the demand for considerable increase in autonomy for East Pakistan. His “six point program” would have transferred most authority to the two provinces, leaving the central government responsible only for defense, monetary policy, and international commerce. Had the results of the election been accepted, power would have transferred to the Awami League. That outcome was not acceptable to Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the chairman of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) with strength among urban workers and Sindhi landed elites, which had won the majority of the seats in the western wing. The result of this standoff was a bitter civil war in which the Indian army, siding with the Bengali freedom fighters, defeated the Pakistani army and established the independent state of Bangladesh.

A defeated and morally devastated Pakistan turned to Bhutto, now president, to lead the country out of this crisis. He launched a number of projects aimed at restoring the confidence of his defeated people. These included the framing of a new constitution, initiating a nuclear weapons program, representing the country as a leader of the Islamic Conference, and expanding the role of the government in managing the economy. The constitution of 1973 envisaged a federal parliamentary structure with a fair amount of autonomy granted to the four provinces of Punjab, Sindh, North West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), and Baluchistan.

Bhutto subverted many aspects of his constitution after taking over as prime minister, showing little respect for the constitution’s federal provisions. The promise that the provinces would be allowed greater autonomy was not fulfilled; he was also intolerant of the rule by the opposition parties in the provinces in which his PPP did not have a commanding presence. When he called for another election, there was an impression that he was looking for a more solid majority in the national legislature that would allow him to amend the constitution toward a more centralized presidential system. The elections held in 1977 showed a massive victory for the PPP, but the opposition argued that there was widespread electoral fraud and took to the streets, leading to deadly violence between opposition activists and security forces. The postelection political violence and instability provided a pretext for military intervention by General Zia ul Haq, Bhutto’s handpicked chief of the army. Two years later, on April 4, 1979, General Zia ordered the execution of Bhutto, who had earlier been sentenced to death by the Lahore High Court on the charge that he was involved in a conspiracy to assassinate a political opponent.

General Zia did not abrogate the constitution as his two predecessors had done but rather set it aside, promising to restore it after six months, yet it was eight years before elections were held under the constitution. Unlike the 1970 and the 1977 elections, political parties were banned and candidates were to run as individuals. This National Assembly passed the Eighth Amendment to the constitution; its most important clause was the infamous article 58.2(b), which gave the president the authority to dismiss the prime minister, dissolve the National Assembly, and appoint a “caretaker” administration responsible for supervising the next general election. With these powers in hand, President Zia handpicked Mohammad Khan Junejo, a Sindhi politician, who had risen to prominence during the period of Ayub Khan. But Zia misread Junejo; the prime minister proved to be independent, proceeding in a different direction from the president. The two clashed over Afghan policy. From 1979, Pakistan had partnered with the United States to launch the mujahideen insurgency to expel the forces of the Soviet Union from Afghanistan. The prime minister opposed the conflict and the toll it was taking on Pakistan. The president wanted more time during which Pakistan should take the responsibility for transferring power to a system of governance that would be durable and bring stability and security. Junejo prevailed, and in February 1988, Pakistan signed the Geneva Accord with Afghanistan, which was guaranteed by the Soviet Union and the United States.4 Three months later, Zia dismissed Junejo, invoking article 58.2(b) of the amended constitution. Three months later, General Zia was killed in an airplane crash that remains unexplained.

All through the time that he ruled the country as president, General Zia continued to hold the position of the Chief of Army Staff (COAS). General Aslam Beg, the deputy chief at the time of Zia’s death, did not take over as president but instead invited Ghulam Ishaq Khan, the chairman of the Senate, to take over as acting president. Khan, immediately after assuming his office, ordered that elections be held in October 1988, as required by the constitution. The PPP, led by Benazir Bhutto, won a majority, and Bhutto was invited to become prime minister. But Bhutto was unable to exercise all the authority guaranteed by the constitution. She was constrained by an informal extraconstitutional “troika” arrangement, in which the president and the COAS shared power with the elected prime minister, effectively the junior member.

In the 1990s, presidents, with the backing of the COAS, freely used article 58.2(b) of the constitution to remove elected prime ministers. Ghulam Ishaq Khan fired two prime ministers by using this constitutional provision, Benazir Bhutto in 1990 and Nawaz Sharif in 1993. His successor, Farooq Leghari, used it against Bhutto in November 1996 to cut short her second tenure. This period of quasi-civilian rule was to prove as turbulent as the eleven-year period immediately after independence, from 1947 to 1958. Seven prime ministers were in office during the 1988–1999 period, only four of whom were elected, with the remaining three appointed under various “caretaker” arrangements. Mian Nawaz Sharif tried to bring stability to this chronically unstable arrangement by dismissing General Pervez Musharraf from office as COAS. The attempt failed, and the army took power on October 12, 1999; Musharraf designated himself first as chief executive and then as president following a rigged referendum. Following the precedent of General Zia ul Haq, Musharraf remained in uniform until the fall of 2007, when he appointed General Ashfaq Pervez Kayani as COAS. Truly democratic rule has been established only since 2008, following protests that forced Musharraf from the presidency, elections that brought the PPP back to power and Asif Ali Zardari to the presidency, and the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment in 2010, which removed the president’s ability to dismiss Parliament.

Can we draw from this political narrative a theory to explain Pakistan’s political evolution from the time of its birth to the time when democracy came to be established in an unsteady way as the preferred system of governance? Several scholars have made such an attempt, most recently Anatol Lieven in his masterly work, Pakistan: A Hard Country.5 Pakistan, an invented country, was faced with more challenges than was the case with its neighbor, India. Where India succeeded, Pakistan failed, because the nation-building efforts in the two countries had different objectives. In the case of India, the effort was to create a political order that could encompass a population of enormous religious, ethnic, and linguistic diversity. In the case of Pakistan, the idea was to make a nation out of a common religious identity. Posed this way, nation-building efforts should have been at least as onerous for India as they were for Pakistan, yet the absence of durable institutions from which a political order can be built in the latter severely constrained the efficacy of state building. Moreover, the assertion of groups from the military to minority groups to landed classes placed added burdens and obligations on a state unable in the first instance to place these particularistic concerns within a common political order.

As a result, there remain a number of unresolved group conflicts in Pakistani society. To begin with, the interests of the military, as a highly organized and centralized centripetal institution, have to be reconciled with those of the many centrifugal political organizations that act from diverse but parochial interests in cities and towns, representing industries, sectors, professions, languages and dialects, biradari communities, and religious sects. These interests provide both resilience and weakness to the political system and provide the context for the sustained distributional conflicts that characterize Pakistan’s political economy.

PAKISTAN’S POLITICAL ECONOMY, 1947–2008

When Pakistan achieved independence, it did not have the capacities of a functioning state. That was not the case for India, which could simply take over central institutions from the British Raj. They inherited a well-developed capital city, a well-staffed central government, a central bank, and a treasury to handle government’s finance. The British left foreign exchange reserves to the partitioned states, 17 percent of which were to be given to Pakistan as its share of these “sterling balances.” Yet none of these were immediately available to Pakistan. It had to create a new state out of nothing. Karachi was chosen as the capital largely because it was the birthplace of Mohammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, and it had some facilities for housing the government because it was then the capital of Sindh, a province of British India. But Karachi’s “physical plant” was not adequate to accommodate a national government. It was for this reason that the decision was taken to maintain the military establishment in the garrison town of Rawalpindi a thousand miles to the north, from where the British had run their “northern command.” This separation of the civilian and military capitals was to profoundly affect the country’s political and economic development. It took the new government almost a year before a central bank was established in Karachi; Jinnah, as governor-general, inaugurated the new State Bank of Pakistan on July 1, 1948, a few weeks before he died. Even then, India did not deliver Pakistan’s share of the sterling balances; it took a trip to New Delhi by Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan and intervention by Mountbatten and Gandhi, before the Indian government released the reserves Pakistan was owed.

Compounding these problems was the arrival of eight million refugees from India, while six million Hindus and Sikhs emigrated to India. At the time of Partition, the provinces that became Pakistan had a population of thirty million; thus, twenty-four million people had to accommodate eight million immigrants, many of them poor farmers and urban dwellers forced to migrate from eastern Punjab and cities in northern and western India due to the sectarian violence that accompanied Partition.6 In terms of GDP growth, the country initially performed poorly, when the national product increased by only 3 percent a year, close to the rate of increase in population.

Pakistan’s economic performance was transformed under General Ayub Khan. In the “development decade” of the 1960s, a number of Western scholars regarded the country as the model of economic development that could be followed by other developing countries.7 During Ayub Khan’s eleven years in power, GDP increased at an average annual rate of 6.7 percent, with the economy more than doubling during this period. The inequitable distribution of the fruits of development would, however, lead by the end of the decade to resurgent Bengali nationalism against the central state, the 1971 war, and the independence of Bangladesh.

In addition to bringing political stability, Ayub Khan’s approach to economic management had a number of salutary features that enabled economic growth. Ayub Khan brought a highly centralized approach to political and economic management. This had both positive and negative results. To help the government manage the economy, Ayub Khan strengthened the Planning Commission, appointing himself as its chairman. A full-time manager was hired from among the senior officers of the Civil Service of Pakistan to run the Commission. The Commission was given the task of writing and implementing five-year development plans. The Second Plan, which covered the 1960–1965 period, remains to this day the most successful planned effort by Pakistan.8 The second important feature of the model was its emphasis on the development of the private sector. The government actively cultivated investment from migrant trading and banking communities in order to create an industrial bourgeoisie and facilitated it with the help of a trade and credit policy that provided some protection to domestic producers while providing them with capital through publicly managed industrial credit agencies.9 Value added in the manufacturing sector increased by an impressive 17 percent a year during the Ayub Khan period.

The third part of the model was to bring discipline to the use of public sector resources by the development agencies responsible for launching and implementing a variety of government-funded projects. The most successful example of this was the Water and Power Development Authority, which carried out massive irrigation and power projects funded by international development agencies.

The rate of growth in GDP picked up because of the increase in the rate of investment; it increased by 8 percentage points between the 1950s and the 1960s. This spurt in investment was possible because of the large flow of external finance, the result of Pakistan’s Cold War alignments with the United States. Pakistan joined a number of U.S.-led defense alliances and was rewarded with large amounts of aid. This was to set a pattern followed in the future. The easy availability of foreign finance has meant that the country made little effort to increase domestic resource mobilization, with tax collection averaging 10.6 percent of GDP since 1991. Dependence on external capital flows also made the country highly vulnerable and subject to the strategic interests of foreign powers, which has contributed to Pakistan’s recent economic crisis, after a breakdown in relations between Islamabad and Washington in 2011 and a shift in U.S. strategic focus, on which more below.

The model, emphasizing rapid industrial growth, neglected its distributional affects. Many felt that a narrow, Karachi-based economic elite had captured much of the benefits of state-led industrialization.10 This feeling of relative deprivation contributed to a mass movement that demanded participation by the citizenry in both the political and economic life of the country. Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, a former foreign minister under Ayub, exploited this sentiment and launched a new political party, the PPP, which promised to bring “Islamic socialism” to the country.

Bhutto came to power in December 1971 and challenged the Ayub economic model on distributional grounds.11 He largely dismantled the institutions Ayub Khan had constructed, reversing most of the policies of industrial promotion. His populist policies nationalized large-scale private enterprise, bringing under the control of the government industrial, financial, and commercial enterprises of significant size. Public-sector corporations were given the authority to manage these enterprises and also to make new investments in the sectors for which they had responsibility.

Bhutto did not limit his nationalization policies with the real sectors of the economy. He also brought under government’s control a number of private-sector educational institutions, to bring equality in the delivery of social services. The prime minister believed that these institutions only bred elitism that retarded the progress toward his Islamic socialism. Bhutto’s policies and divisive politics did a great deal of damage to the economy and to the development of the country’s large human resources. The rate of GDP growth declined by almost 3 percentage points and came close to the rate of increase in population. Moreover, the incidence of poverty increased during the period. But the Bhutto years encouraged a winner-takes-all conflict over political power and economic resources, as Bhutto himself diverted enormous resources to favored clients while punishing other groups through expropriation of resources and even coercion.

President Zia ul Haq relied on technical managers to rescue the economy from the difficulties created by the Bhutto administration, even while his government favored his own clients, including Punjabi industrialists like Mian Muhammad Sharif. Under technocratic finance ministers Ghulam Ishaq Khan (1977–1985) and Mahbubul Haq (1985–1988), Pakistan essentially went back to the mixed model of economic growth it had followed during the period of President Ayub Khan. The rate of growth in GDP went back to 6.7 percent a year and the rate of increase in income per head of the population to nearly 4 percent per annum. As was the case during the period of first military rule, the United States provided large amounts of foreign aid in exchange for its support against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan.

President Zia ul Haq’s death coincided with the pullout by the Soviet Union from Afghanistan and the consequent loss of strategic interest by the United States in supporting Pakistan economically. In response to IMF and World Bank conditionalities in the 1990s, Pakistan had begun to implement “Washington Consensus”–consistent structural reforms. This put private enterprise at the forefront while the economy was opened up to global trade and foreign investment. This shift in policy stance should have pleased the officials in Washington, but the nuclear tests in 1998 under the premiership of Nawaz Sharif led to the imposition of economic sanctions. Denied access to foreign capital, the rate of growth plummeted to less than 4 percent a year at the end of the decade.

Further, weak democratic governments, alternating between Nawaz Sharif’s PML-N and the PPP under Benazir Bhutto, in the 1990s further calcified the conflict between proprietary groups over political power and economic resources. The military refused civilian oversight and fought for control over a substantial portion of the state’s resources, and the economic clients of the various political parties at national and provincial levels competed over the nonimplementation of reform measures, public investment in private ventures, and other forms of endemic corruption that characterized the period. Even as conflict over resources increased, the external support to the state stagnated; the gradual withdrawal of U.S. development aid throughout the decade led to multiple balance-of-payments crises and World Bank–IMF adjustment programs, most of them not seriously implemented.

General Pervez Musharraf’s coup against the Sharif government further decreased the legitimacy of the Pakistani state in the eyes of the United States. President Clinton’s spring 2000 visit to South Asia almost completely bypassed Pakistan, and the president refused to shake hands with Musharraf. After the attacks of September 11, 2001, there was a dramatic improvement in Pakistan’s economic situation as the Musharraf regime aligned itself with the United States as a frontline state in the global war on terror.

For the third time in its history, the rate of growth in the economy picked up, averaging close to 7 percent a year. Pakistan’s realignment led the United States to renew its economic commitments. Not only did large amounts of aid begin to flow into the country, but Washington also helped Pakistan with debt forgiveness, which significantly lowered its repayment liabilities. The IMF also came in with a large program with comparatively soft conditions. Along with generous capital flows, the country’s economy was reasonably well managed by a group of technocrats, some of whom were called in from abroad when General Musharraf assumed political control. The inflow of these resources enabled the Musharraf regime to paper over the group conflict over economic resources that had been institutionalized in the 1990s.

This broad overview of the institutional foundations behind Pakistan’s economic performance leads one to conclude that the country is structurally able to produce reasonably high rates of economic growth if it is competently governed, political conflicts are managed, and significant amounts of foreign capital inflows are available. As we will see from the analysis offered in the following section, none of these conditions are now evident, which suggests that lowered rates of growth, along with their attendant social and political impacts, may be present for some time to come.

TOWARD A NEW POLITICAL ORDER AND ITS ECONOMIC COST, 2008–2014

Although the parties that had relentlessly opposed rule by the military won the election held in February 2008, the armed forces did not immediately pull back to the barracks. General Pervez Musharraf tried to stay in power as president. But he was eventually persuaded to leave the presidency in part because the new military commander made it clear that the president did not have his support.

Asif Ali Zardari, Benazir Bhutto’s widower, acted to build a political coalition in order to take control of the presidency. He first cultivated Nawaz Sharif, the head of the rival PML-N, to work with him to oust Musharraf. Sharif was even more opposed to Musharraf following the 1999 coup and his decade-long exile under threat of anticorruption charges in Pakistan. He joined a “grand coalition” organized by Zardari when Yusuf Raza Gilani, his choice for premiership, was sworn in as prime minister. The PML-N was given several important portfolios, including that of finance, but the coalition quickly fell apart. In May 2008, the PML-N left the government, leaving the PPP, along with junior partners, such as the Awami National Party (ANP) and the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), fully in charge. By that time, the PPP cochairman had received the indication that the military would not support Musharraf’s continuation in office. Musharraf, now threatened with impeachment, resigned in late August and entered exile in London. Zardari was elected president a month later.

There was an expectation when the democratically elected government replaced military rule in March 2008 that it would uphold the rule of law (table 6.3). That was the spirit behind the Charter of Democracy signed on May 14, 2006, in London by the leaders of the two main political parties. Political parties joined the civil society movement for the restoration of Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry, who had been removed by Musharraf. Once returned, the Supreme Court controversially held that the National Reconciliation Ordinance, an order of amnesty for politically motivated corruption charges that Musharraf had signed in 2007 in order to allow a restoration to power, was unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court’s decision implied the revival of these cases, including one pending in a Swiss court, which implicated Bhutto and Asif Ali Zardari in a kickback case in which it was alleged that the couple had received tens of millions of dollars in return for the grant of a large contract. The court instructed the government to write to the Swiss authorities to restore the case. Prime Minister Gilani refused to comply, maintaining that the Constitution gave Zardari, as president, immunity against prosecution. This led to the launch of contempt proceedings by the Supreme Court against the prime minister.

On April 26, 2012, the court convicted the prime minister of having committed contempt, but Gilani again defied the court by not resigning his office. The court acted again on June 19 and ordered his removal, issuing a “short order” that instructed the chief election commissioner to remove the prime minister from membership of the National Assembly and also instructed the president to convene the National Assembly to elect a new prime minister. This time the PPP government chose to comply but in a manner that further plunged the country into political chaos and economic uncertainty.

TABLE 6.3 PAKISTAN’S RANKING IN CORRUPTION PERCEPTION INDEX (CPI)

| YEAR |

SCORE |

RANK |

| 1995 |

2.25 |

39/41 |

| 1996 |

1 |

53/54 |

| 1997 |

2.5 |

48/52 |

| 1998 |

2.7 |

71/85 |

| 1999 |

2.1 |

87/99 |

| 2000 |

— |

— |

| 2001 |

2.3 |

79/91 |

| 2002 |

2.6 |

77/102 |

| 2003 |

2.5 |

92/133 |

| 2004 |

2.1 |

129/145 |

| 2005 |

2.1 |

144/158 |

| 2006 |

2.2 |

142/163 |

| 2007 |

2.4 |

138/179 |

| 2008 |

2.5 |

134/180 |

| 2009 |

2.4 |

139/180 |

| 2010 |

2.3 |

143/178 |

| 2011 |

2.5 |

134/183 |

| 2012 |

2.7 |

139/174 |

| 2013 |

2.8 |

127/177 |

NOTE: VERY CLEAN = 9.0–10; HIGHLY CORRUPT = 0.9–2.0.

SOURCE: TRANSPARENCY INTERNATIONAL, ALL ISSUES OF CORRUPTION PERCEPTION INDEX FROM 1995 TO 2014.

The nomination of Raja Pervez Ashraf, a former power minister accused of several incidents of corruption as party leader and prime minister, by President Zardari on June 21 did nothing to improve the president’s tarnished image or to begin the process of bringing the country out of deep political and economic crisis. Ashraf went on to receive 211 votes, a majority in the National Assembly. The opposition was generally appalled by the president’s move. According to an assessment by the Financial Times, “in a move that observers said would do little to arrest the mounting political crisis in the South Asian country, Raja Ashraf stepped down last year as water and power minister amid allegations of corruption and failure to end the country’s chronic electricity shortages.”12 The press had begun calling Ashraf “Raja rental,” a reference to the rental power scam investigated first by the Asian Development Bank and subsequently by the Supreme Court. The newspaper Dawn summed up the reaction to Ashraf’s election in an editorial: “The nomination of Raja Ashraf was a snub to millions of citizens who are suffering long hours of load shedding in the Pakistani summer. In the face of electricity cuts, the former water and power minister was an insensitive choice—and an unwise one, in an election year—sending a signal that the PPP is unconcerned about one of the nation’s most painful problems. Political considerations were obviously at stake.”13

The perceived corruption and incompetence of the PPP coalition government placed the party at historically low levels in public opinion in the months before general elections in May 2013. Political pressure on the government in early 2013 was increasing through mass rallies by Imran Khan and his Pakistan Tehreeke Insaaf (PTI) party and a march on Islamabad organized by the charismatic antigovernment cleric Tahirul Islam Qadri. In March, the tenure of the National Assembly ended, and the Election Commission, on the recommendation of a parliamentary committee, appointed the retired judge Mir Hazar Khan Khoso as caretaker prime minister. The election campaign over April and May was marred by violence in the northwest and in Karachi, with the Taliban targeting candidates and rallies of the PPP, the ANP, and the MQM. The elections themselves, held on May 11, presented an anti-incumbent wave, with the PML-N winning seats just short of a full majority, and the PPP decreasing its representation in Parliament to less than a quarter of its previous seat strength, though still managing to outperform Imran Khan’s PTI.

The 2013 elections in Pakistan represented a watershed in the resilience of emergent democratic institutions; this was the first time in Pakistan’s history that a democratically elected government relinquished power and another took up power. Following parliamentary elections, the PML-N candidate for president, Mamnoon Hussain, was elected after Zardari relinquished office in July 2013, two months ahead of the end of his term. General Kayani, the COAS, retired from the army in November 2013 in favor of the next in line, Raheel Sharif, thus presenting an instance of orderly succession in military leadership as well.

The political system in Pakistan is currently not without its challenges; each province is governed and represented in Parliament by a different party or set of parties, and the tensions between Pakistan and the United States over the drone program continue. But the political system has cleared a number of serious hurdles over the course of the year, even though recent institutional resilience has yet to translate to perceptions of political order and economic upturn, as key economic crises—particularly over power—and political conflict with outgroups, such as the protests of Imran Khan and Tahirul Qadri, continue.

ECONOMIC PERFORMANCE, 2008–2014

Restoration of democracy after decades of military rule was expected to cure Pakistan of many of its economic ills. The military had not governed without interruption, as it had in many other Muslim countries in the second half of the twentieth century. In Pakistan’s case, it had ruled in three long spurts—1958–1971, 1977–1988, and 1999–2008—a total of 33 years. Even when it was not in power, it continued to exercise a considerable amount of influence on the making of public policy. When the military was directly in control, the economy did relatively well; its three growth spurts were all under the martial rule. Yet one of the important reasons for the economy’s superior performance during these periods was undoubtedly the large inflows of external capital, coinciding with the early Cold War, the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, and the global war on terror.

This was possible as the military rulers were able to take advantage of international crisis and quickly align the country with Western powers, particularly the United States. This happened during the first military presidency (1958–1968) when Ayub Khan brought Pakistan into a number of defense pacts with the United States following the Korean War and the freezing of the early Cold War decades. It happened again under General Zia ul Haq (1977–1988) when Islamabad agreed to assist Washington in the latter’s effort to expel the Soviet Union from Afghanistan. And it happened for the third time under General Pervez Musharraf when practically overnight Pakistan did 180-degree turn and gave up its support for the Taliban regime in Afghanistan and became the United States’ partner in throwing the Islamic regime out of Afghanistan.14 In each case, Washington rewarded the country through the provision of copious amounts of economic and military assistance, which enabled Pakistan to avoid facing distributional conflicts between increasingly assertive political groups.

The provision of these external resources may have contributed to a problem of moral hazard, with Pakistani policymakers, sure of their country’s strategic importance, implicitly relying on bailouts in times of crisis. In Pakistan’s case, this has happened repeatedly, with the United States, China, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the IMF coming to the country’s rescue at different times in its troubled economic history. An IMF bailout was arranged in September 2013, in order to help Pakistan out of economic difficulties brought on by a current account deficit that is unfinanced by foreign capital inflows.

The first eighteen months of the PML-N tenure has brought growth up above 4 percent and above-target performance in manufacturing but underperformance in agriculture and services. Balance-of-payments crises have abated somewhat: foreign direct investment has more than doubled to $2.9 billion, and there was an external account surplus of $1.9 billion in July 2013–April 2014, as opposed to a worrying deficit the year before.15 While Pakistan has survived the crises of 2013, in large part due to assistance from the IMF and Saudi Arabia, economic growth is still lackluster and does not signify progress toward the structural reforms required for sustained growth in the medium term.

Pakistan also remains overreliant on external support and not immune to exogenous shocks that could plunge the country back into economic crisis. Of much concern is Pakistan’s foreign debt, accumulated over decades of economic relationships with the United States, the rest of the Paris Club of creditor countries and the IMF and amounting to $65.4 billion in the summer of 2014. External debt servicing in 2014 reached $6.8 billion, which was 80 percent of central bank reserves for the year.16 Combined external and domestic debt servicing of over $11.5 billion constitutes about a third of the country’s total revenues and exceeds tax revenues when adjusted for provincial shares.17 The State Bank of Pakistan further warns of a debt servicing trap, with weak tax revenues leading to greater fiscal deficits and an even greater share of revenues committed to debt repayment and servicing. The dual challenges of the inability to create a domestic settlement that involves taxing resources in order for the government to function and overreliance on external aid (largely in the form of loans) means that economic instability and fiscal pressure will be reproduced through debt servicing requirements for many years to come.

Why was the promise of 2008, when democracy returned to the country in a stable form, not fulfilled? This question assumes a set of premises: that democracy is good for development and sustainable economic growth; that it is good for the more equitable distribution of the fruits of growth; that it is good for giving people with diverse and seemingly irreconcilable interests and objectives the opportunity to resolve their differences; that it is good for providing the citizenry with institutional outlets they can use to express their frustrations; and that it helps those states that practice it to live in peace with their neighbors. If these premises hold, we should expect that Pakistan would have benefited materially in several different ways from the return of democracy. The move from a political system explicitly dominated by military priorities to one that is more open and governed by representatives of an active electorate should have produced greater welfare, confidence, investment, and economic growth. Yet such promises have not come into fruition a half decade from the transition to democracy.

Of the five benefits of democracy listed above, only one has thus far produced satisfactory results for Pakistan. And Pakistani citizens have used democratic institutions to express their frustrations and anxieties about their circumstances. Most citizens today are worse off than they were five years ago, when the political system began to change. Yet there is no widespread rebellion against the state. The extraconstitutional agitations of Imran Khan’s PTI and Qadri’s Pakistan Awami Tehreek, with implicit support from the military,18 might have damaged the credibility of the current government but have thus far been unable to overturn it. Citizens of Pakistan seem to differentiate between the validity of Imran Khan’s charismatic critiques against corrupt public institutions and the political practices of his political party and that of Qadri in challenging the democratic system.

The other four potentially positive outcomes are still not evident. In terms of the democratic peace dividend, after relatively stable relations between India and Pakistan over the last decade, tensions have increased again over Kashmir, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi publicly committing to a policy of no tolerance with regard to insurgents with ties to Pakistan. These recent tensions have stalled the ongoing pursuit of arrangements that put greater emphasis on producing economic benefits for both sides, through trade.

Second, even after an election in which the government changed hands to a more pro-business party, the economy is in very bad shape. The rate of growth has slowed down to the point where it is not much more than the rate of increase in the country’s population. This means that not much is being added to the national product and that those who occupy lower rungs of the income distribution ladder cannot draw benefits from the little economic change that is occurring. In fact, the distribution of income has worsened since 2008. There is an increase in both interpersonal and interprovincial inequality. Two of the country’s four provinces, the Punjab and Sindh, have done relatively well, while the other two, Baluchistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, have been left behind (table 6.4).

Even in the better-performing provinces, there are districts that have fallen behind. And there is growing violence in the country, a consequence of both the inability of state agencies to interdict violent actors and perhaps of the people not being able to—or not willing to—solve their differences through democratic institutions. Karachi, a city with close to twenty million people, is the most ethnically, linguistically, culturally, and religiously diverse city in the country. It has twice exploded into violence since the return of democracy.

Does this mean that democracy has failed in Pakistan; that for some reasons peculiar to the makeup of the country, democracy has not delivered? The short answer to this question is no. But the question needs a longer answer on why democracy seems to be failing to provide material benefits to Pakistan. First, although democracy has been established in Pakistan, it has not been fully consolidated in such a way as to guarantee that democratic institutions have a legitimate monopoly over policy formulation and implementation.19 Significant aspects of the Pakistani polity are beyond the reach of the democratic authority of elected governments and subordinate administrators, from governance in the tribal agencies to oversight of the overseas assets of the richest Pakistanis. Second, political institutions in Pakistan must become more inclusive if they are to be effective and produce sustained economic development.20 As more individuals and organized groups are brought into the policy process, there will be less exit and resistance and more scope for the policies and practices of the state to make a difference in the lives of the Pakistani population. Ultimately, Pakistan needs a more durable and comprehensive political settlement among powerful political groups in order to both consolidate democracy and ensure that an economically enabling environment is not challenged by winner-takes-all politics.

TABLE 6.4 ALLOCATION OF FUNDS TO PROVINCES

| PROVINCE |

ALLOCATION (%) |

| Punjab |

51.74 |

| Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

14.62 |

| Sindh |

24.55 |

| Baluchistan |

9.09 |

NOTE: PERCENTAGE OUT OF RS 1,728,113 ALLOCATED FOR PROVINCES IN 2013–2014 BUDGET.

There is hope that the reshaping of the structure of government following the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the rebalancing of federalism will improve the quality of governance by bringing the state closer to the people. But there is also anxiety that the devolution of authority to the provinces could cause disruption in a number of areas. There is a particular concern that unless the process of devolution is managed carefully, it could result in the deterioration of public services to the poorer segments of the population.21 More broadly, these institutional reforms could form the basis of a broader settlement that allows for more resources for public and private investment while delimiting the power and resources of powerful groups, but this requires both political will and flexibility that is not evident in this government, reliant as it is on a particularly narrow slice of the Pakistani political universe.

CONCLUSION

The 2013 IMF program presents the first real opportunity for addressing structural problems in the country, such as chronic fiscal deficits due to rampant tax evasion and productivity-sapping inequity in the provision of key social and economic inputs, such as foodstuffs and energy. The PML-N government will have to address the issues of the limited capacity of the state to raise sufficient resources for delivering public goods, provide sufficient energy resources for industrial output as well as household consumption, and at the same time reduce income inequalities across classes and regions, control inflation, and improve the security situation to increase confidence in the country. The 2013 elections represented the electorate’s feeling that the PPP coalition was incapable of addressing these many problems, and it remains to be seen whether Nawaz Sharif’s administration will be more effective over the long term, particularly after shocks to its legitimacy brought on by the PTI/PAT agitation.

Yet the capacity of the Pakistani state to implement such reforms is questionable, given historical experience of powerful groups successfully resisting reform and the narrowness of public debate. In addition, the adjustment program has not been embedded in a broader strategy of economic development that engages a broader range of stakeholders in society.22

Pakistan is still missing a durable political order, in which powerful groups agree to delimit their extraconstitutional agitations and outsized grabs for state resources, in order to enable public and private investment and create a politically stable institutional environment. Absent such a compact that would allow for sustainable national development, Pakistan remains dangerously dependent on the support of bilateral and international institutions and their calculations that Pakistan is “too big to fail.” And yet, as Pakistan has seen time and time again, such external support is both fickle and politically costly, especially in terms of state sovereignty.

In the future, the nature of this dependence may also change. As the current American military focus on Afghanistan wanes and Pakistani commitment toward stability has increasingly been brought under scrutiny by Congress, economic aid is begrudgingly provided by an international community that recognizes that Pakistan is, in terms of international security and regional politics, simply too big to fail, and by Gulf donors who seek their own political interests in South Asia. In the course of time, this evolution may have major geopolitical implications.

NOTES